Microcast #107 — Apocalyptic events

I found the best Wikipedia page, which reminded me of an awesome episode of the ‘Hardcore History’ podcast.

Show notes

- List of dates predicted for apocalyptic events (Wikipedia)

- Prophets of Doom (Hardcore History)

(Note: Dan Carlin sells older podcast episodes on his blog. You can also access the episode for free here)

Microcast #106 — Conversational configuration

Thinking about ways in which users can interact with systems in conversational ways which allow apps, platforms, and services to configure themselves to meet user needs.

Show notes

- Android users can now use conversational editing in Google Photos (The Keyword)

- Booking.com Enhances Travel Planning with New AI-Powered Features for Easier, Smarter Decisions (Booking.com)

- Discourse (Discourse.org)

Microcast #105 — Being defeated is optional

Resurrecting microcasts after 18 months (no intro/outro music yet!) with musings on quotations from Roger Crawford and Epictetus:

Show notes

- Epictetus (Wikipedia)

- The Enchiridion (Internet Classics Archive)

- Roger Crawford quotations (Goodreads)

The project of building alternatives to Big Tech is colliding with American authoritarianism

Laurens Hof writes a newsletter called Connected Places which really is a must for anyone interested in federated social networks and decentralisation in general. As someone who has led a Fediverse project I retain a professional interest, and of course I have a personal interest as someone with active Mastodon and Bluesky accounts (as well as less active Pixelfed and Bonfire accounts).

This particular post about ‘Blueskyism’ is a difficult one to quickly summarise, as it’s nuanced, but essentially Hof explains the situation that Bluesky (the company) found itself in last week after the assassination of Charlie Kirk. Essentially, because Bluesky (the network) isn’t very decentralised the moderation practices of Bluesky (the company) affect almost everyone on Bluesky (the network).

Although Hof doesn’t mention it specifically, there are some calling the assassination a ‘Reichstag fire’ moment for the US — i.e. a pretext to crack down on the political left. Bluesky (the network) is being painted by those on X (including its owner Elon Musk) as a ‘leftist space’ which needs to be ‘dealt with’ in some way. As it is not very decentralised, someone could buy Bluesky (the company) and effectively shut it down. What’s easier, when you have someone like Trump in power, as we’ve seen with Jimmy Kimmel is that an executive order, threats of tariffs, or some other abuse of power, can effectively silence free speech.

The state of open social networks has rapidly changed. Building social networks that can overtake big tech platforms was always an inherently political project, but recent developments in America have added a new dimension of urgency. Centrist pundits have made an effort to paint Bluesky as a leftist space. Outrage merchants on X share and amplify fabricated narratives about Bluesky users celebrating Kirk’s death, while fascist voices grow louder in their calls to shut down and prosecute all democratic and leftist spaces, which now includes Bluesky. Now, with US congressional demands for censorship and calls to remove Bluesky from app stores, the project of building alternatives to Big Tech is colliding with American authoritarianism.

[…]

Building resilient networks in 2025 means not just architecting against enshittification, but against authoritarianism. The infrastructure for ‘credible exit’ that Bluesky promotes may soon need to encompass not just leaving one ATProto platform for another, but also factor in what happens to the entire open social ecosystem when app stores and governments align against it. When authoritarian governments and tech oligarchs coordinate to eliminate spaces for political opposition, the shape of the solutions, both technological and social, need to account for this new threat. The challenge now is to imagine and build infrastructure that can survive not just bad business decisions, but coordinated political suppression. Building resilient social networks now means preparing for a future where being labeled as a ‘left’ space can get your app removed from app stores, and where the act of maintaining an open protocol becomes an act of resistance.

Source: Connected Places

Image: Elena Rossini

A brick is always a brick, whatever the reasons of the clown chucking it

It’s hard to argue against the argument by Aditya Chakrabortty in this article for The Guardian that Labour are now simply the warm-up act for Reform UK. Having seen a majority of my fellow countrymen and women vote for Brexit almost a decade ago, it wouldn’t surprise me if they decided to vote in the chief architect, Nigel Farage.

It’s almost like the definition of the sunk cost fallacy: lurching to right and “taking back control” from the EU didn’t do enough, so let’s go even further and “kick out the immigrants,” eh? Utterly, utterly mad. Anything to stop us paying attention to insane wealth inequality and extraordinarily rich individuals acting like they represent the “will of the people.”

I can’t quickly re-find the source, but I remember someone pointing out that — due to a declining birth rate and ageing populations — it won’t be long before many nations will be competing for immigrants.

At the end of last month, Nigel Farage promised mass deportation of practically anyone seeking asylum in this country, even if it meant handing Afghan women over to the Taliban and sending Iranian dissidents to their deaths. To the press, No 10 didn’t so much as raise an eyebrow at the Reform UK leader referring to other humans as a “scourge” or an “invasion”. For the great unwashed, it posted the most extraordinary advert. “Whilst Nigel Farage moans from the sidelines, Labour is getting on with the job,” it read, showing an image of Starmer stamped with “removed over 35,000 people from the UK”. Why vote for the full-fat hatemongers when diet racists will do the job just fine?

Plenty of Labour people will say they aren’t racist at all, and I wouldn’t wish to argue. But one lesson about prejudice I learned fast growing up was to focus on impact rather than quibble about intention. A brick, in other words, is always a brick, whatever the reasons of the clown chucking it.

[…]

“The British people have a far more nuanced view of immigration than the media and political narrative would have us believe,” observes Nick Lowles of anti-fascist organisation Hope Not Hate in his new book, How to Defeat the Far Right. Only one out of 10 Britons is outright opposed to immigration, while many who identify, say, asylum seekers as a huge issue have never met one. Of the top 50 areas in the UK most vehemently opposed to Muslims, Lowles finds that 27 are in the district of Tendring, in Farage’s constituency of Clacton. Yet how much of Tendring’s population is Muslim? Fewer than one out of 200: 0.4%.

Armed with such findings and a historic majority, Labour could easily counter some of the wild extremism. Ministers might point out that “English patriot” Robinson is an Irish passport-holder (up until last summer, anyway) who hunkers down in Spain and has a list of criminal convictions long enough for a tattoo sleeve. Starmer might observe how much of the UK would simply fall apart without migrants and their children – from your local hospital to the school to the care home. How universities are facing collapse without foreign students and their bumper fees. He might even point out – imagine! – that migrants are human too, with their own lives and dreams for themselves and their families. We could get on to the legacy of empire, and about how the climate crisis and poverty force other populations to move.

[…]

History has a habit of giving little men big tasks. Joe Biden had one job: to stop Donald Trump returning to power. His failure will have consequences for the world. Starmer’s one historic role is to stave off the hard right. He is not only failing, he is paving the way for Farage and his crew. The supposed “centrists” are ushering fringe politics into the mainstream and normalising the abhorrent.

But just listen to the speeches and chants made by the extremists. Robinson no longer talks about small boats; he wants his country back. After years of resisting mass deportations as “impossible”, Farage now touts them as the solution. The Overton window is shifting further and further to the right. The ultimate price for that will not be paid by a politician, but by people far from power: an Ethiopian boy, perhaps, with no family, or an Asian kid looking out the window one evening.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Hal Gatewood

Now is the time to be even more aggressive, not to cower in the face of pressure and criticism

Paris Marx, who is back on Ghost after a brief flirtation with Substack, takes a look at social media regulation in a recent post. Comparing the regulatory landscapes in the US, UK, and Australia, he argues that “the perfect is the enemy of the good” when it comes to what he calls the “social media harm cycle.”

As he points out, although the regulations are targeting children under the age of 16, the issues around AI and algorithms on social networks affect everyone. We’ve tried our best to keep our two teenagers off algorithmic social networks until they turned 16, but it’s difficult. And it’s not like there’s a magic “maturity and self-control” switch that is turned on when you reach specific ages.

Instead, and this isn’t something I would have advocated for a decade ago, regulation is required to break the loop of algorithmic addiction. Back in 2012 when my son and daughter were five years old and one year old, respectively, I argued that “The best filter resides in the head, not in a router or office of an Internet Service Provider (ISP).” I’m still anti-censorship, but we’ve managed to allow Big Tech to have far too much control over our everyday lives.

These algorithms are perhaps the most powerful shapers of society at the moment — which is why it’s kicking off everywhere. They’re rage machines.

In the past, I might have been more hesitant about these efforts to ramp up the enforcement on social media platforms and even to put age gates on the content people can access online. But seeing how tech companies have seemingly thrown off any concern for the consequences of their businesses to cash in on generative AI and appease the Trump administration, and seeing how chatbots are speedrunning the social media harm cycle, many of my reservations have evaporated. Action must be taken, and in a situation like this, the perfect is the enemy of the good.

I don’t support the US measures that are effectively the imposition of social conservative norms veiled in the language of protecting kids online. But I am much more open to what is happening in other parts of the world where those motivations are not driving the policy. Personally, I think the Australians are more aligned with an approach I’d support.

They’re specifically targeting social media platforms, rather than the wider web as is occurring in the UK, and the mechanism of their enforcement surrounds creating accounts. So, for instance, now that YouTube will be included in the scheme, that means users under 16 years of age cannot create accounts on the platform — that would then enable collecting data on them and targeting them with algorithmic recommendations — but they can still watch without an account. There are still concerns around the use of things like face scanning to determine age, but in my view, it’s time to experiment and adjust as we go along.

Even with that said, if I was crafting the policy, I would take a very different approach. It’s not just minors who are harmed by the way social media platforms are designed today — virtually everybody is, to one degree or another. While I support experimenting with age gates, my preferred approach would focus less on age and more on design; specifically, severed restrictions algorithmic targeting and amplification, limiting data collection and making it easier for users to prohibit it altogether, and developing strict rules on the design of the platforms themselves — as we know they use techniques inspired by gambling to keep people engaged.

To be clear, the Australians and the Brits are looking into those measures too — if not already rolling out some measures along those lines. These are actions we need to take regardless of the politics behind the platforms, but given how Donald Trump and many of these executives are explicitly trying to use their power to stop regulation and taxation of US tech companies, now is the time to be even more aggressive, not to cower in the face of pressure and criticism.

Source: Disconnect

Image: Declan Sun

People living today are almost never the descendants of the people in the same place thousands of years before

At a time when nationalists, white supremacists, and fascists would have you believe otherwise, it’s worth reminding ourselves that we are essentially a migratory species.

[I]ncreasingly sophisticated analysis of genetic material made possible by technological advances shows that virtually everyone came from somewhere else, and everyone’s genetic background shows a mix from different waves of migration that washed over the globe.

“Ancient DNA is able to peer into the past and to understand how people are related to each other and to people living today,” [Harvard geneticist David] Reich said during a talk at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. “And what it shows is worlds we hadn’t imagined before. It’s very surprising.”

Human populations have been in flux for tens of thousands of years since our emergence from Africa. The details of the still-developing picture are complex, but the overall theme is one of increasing homogenization since human diversity fell from the time when modern humans lived next door to Neanderthals, two strains of Denisovans, and the diminutive Homo floresiensis of Indonesia.

[…]

“The big perspective change from ancient DNA study is that people living today are almost never the descendants of the people in the same place thousands of years before,” Reich said. “Human movements have occurred at multiple timescales, often disruptive to the populations that experience them, and these patterns were not possible to predict and anticipate without direct data.”

Source: The Harvard Gazette

Image: Miko Guziuk

You must not talk about the future. The future is a con.

Emily Segal’s talk at FWB FEST last month was entitled The End of Trends, and this post both embeds the talk and provides an edited transcript (which I appreciate: more people should do this!)

My understanding of the productively ambiguous post is that trying to predict the future based on “trends” is probably best left to AI, which can sift through much more information that humans can. Instead, we should be focusing on the more “grounding” perspective of trying to enrich the present moment.

I like this approach. Goodness knows it’s anxiety-provoking for people like me to extrapolate existing behaviours into the future. While some might say this nullifies effective action, I’d actually argue the opposite: it prevents paralysis and provides a bias towards action in the here-and-now.

In Canto 20 of Dante’s Inferno, Dante and Virgil visit the circle of hell reserved for astrologers and soothsayers. Their punishment for trying to see too far ahead in life is that their heads are twisted backward. Their hair runs down their fronts. They stumble forward while always looking behind them.

Dante breaks the fourth wall here: he says it’s wrong to pity anyone in hell, but he can’t help pitying the soothsayers. I think many of us are in a similar predicament now – trying to move forward while constantly looking backward.

[…]

I often think of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, in which a group of “Foretellers” pool consciousness to answer questions they could not access individually. The weaver in the group maintains tension in the pattern until it breaks, revealing the answer.

And I think of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s caution:

“You must not talk about the future. The future is a con. The tarot is a language that talks about the present. If you use it to see the future, you become a charlatan. … Everything is linked, but nothing is a matter of probability.”

In an age surrounded by probability machines, this perspective is grounding. So I leave you with this: Will you become a novum – a machine-like thinker, a better-than-chance oracle in a human body? Or will you focus on enriching the present, making it better in the moment?

Source: Nemesis Memo

Image: Suraj Raj & Digit

Asking, Doing, or Expressing?

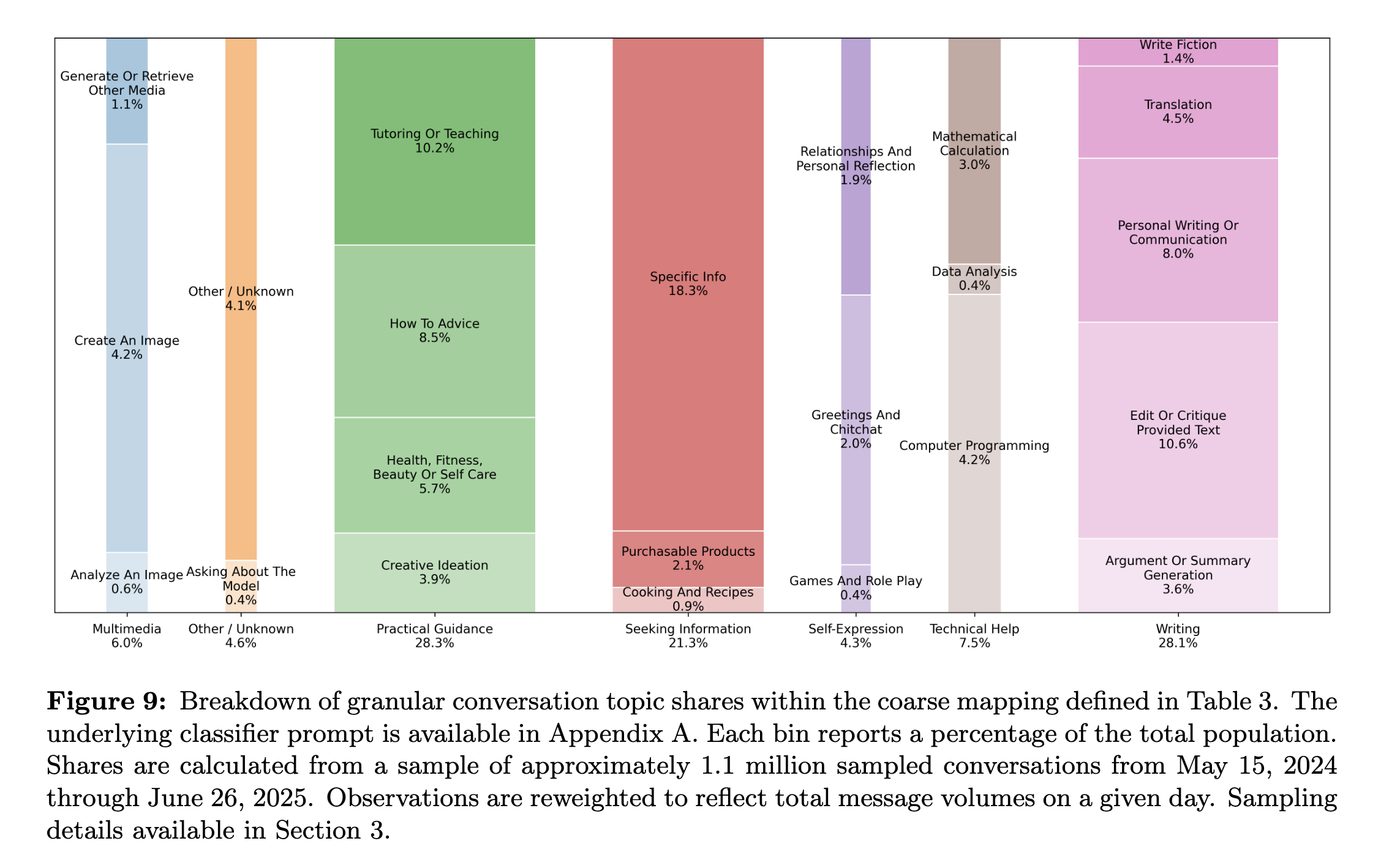

A few months ago, when I shared the work of Marc Zao-Sanders about how people use generative AI, I noted that his “a rigorous, expert-driven curation of public discourse, sourced primarily from Reddit forums” didn’t actually include a methodology.

A few months ago, when I shared the work of Marc Zao-Sanders about how people use generative AI, I noted that his “a rigorous, expert-driven curation of public discourse, sourced primarily from Reddit forums” didn’t actually include a methodology.

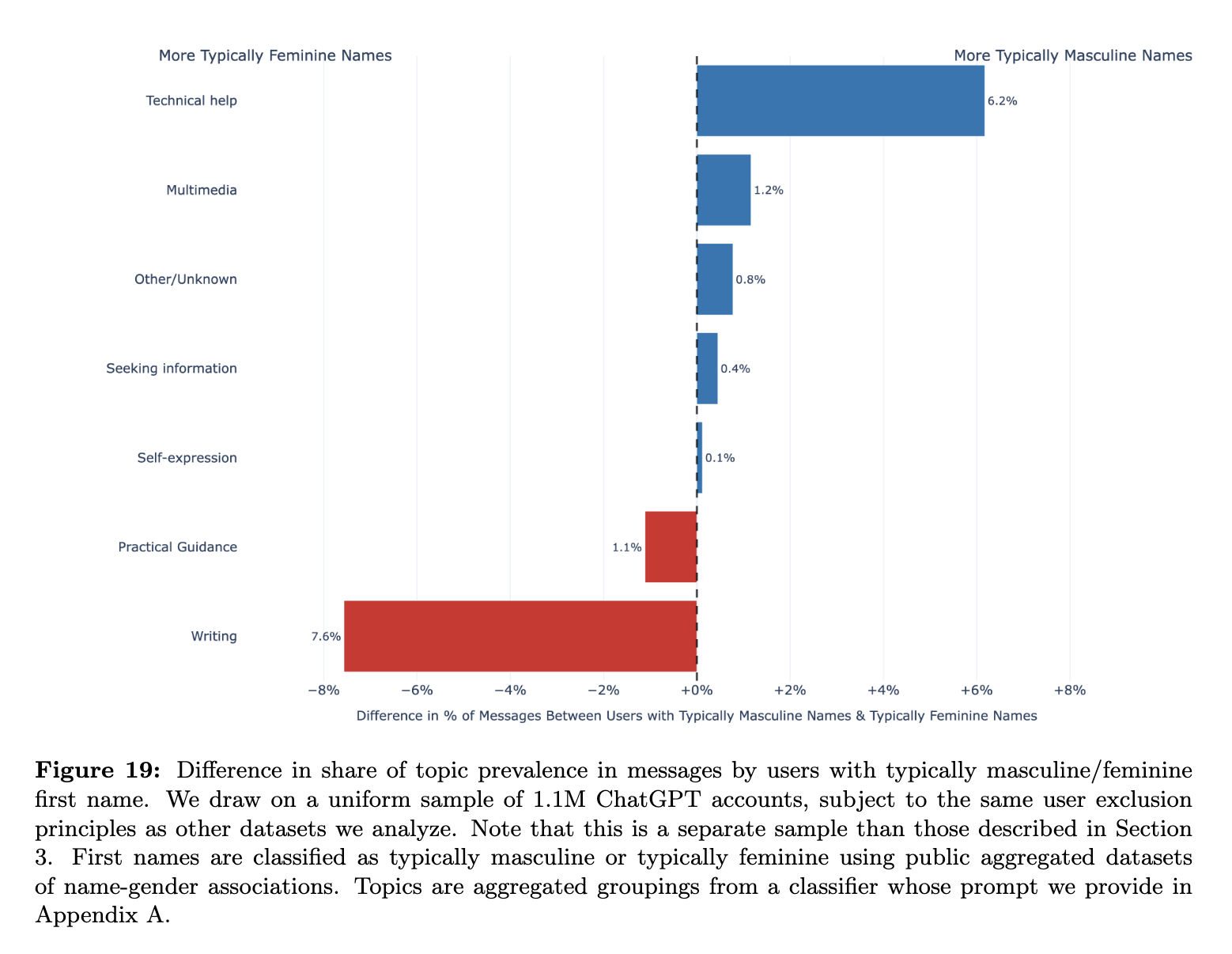

In the last few days, OpenAI has released a paper in collaboration with scholars at Duke University and Harvard University which would suggest that people’s actual use of ChatGPT is… quite difference to the picture that Zao-Sanders gave. To me, that’s unsurprising given that he was sourcing his insights from Reddit, which skews young and male. Interestingly, the demographics of ChatGPT users have changed markedly in the years since it was released. Apparently, in the first few months after it was made available, four-fifths of active users had “typically masculine first names” with that number dropping to less than half as of June 2025. Now, active users are slightly more likely to have typically feminine first names. It seems like different genders use generative AI differently, too (Fig.19).Finally, it’s telling that, as the use of ChatGPT grew five-fold from June 2024 to June 2025 the share of “non-work” uses rose from 53% to 73%. It’s definitely interesting times. Don’t mind me, I’m off to re-watch Her (2013).

Interestingly, the demographics of ChatGPT users have changed markedly in the years since it was released. Apparently, in the first few months after it was made available, four-fifths of active users had “typically masculine first names” with that number dropping to less than half as of June 2025. Now, active users are slightly more likely to have typically feminine first names. It seems like different genders use generative AI differently, too (Fig.19).Finally, it’s telling that, as the use of ChatGPT grew five-fold from June 2024 to June 2025 the share of “non-work” uses rose from 53% to 73%. It’s definitely interesting times. Don’t mind me, I’m off to re-watch Her (2013).

First, we show evidence that the gender gap in ChatGPT usage has likely narrowed considerably over time, and may have closed completely. In the few months after ChatGPT was released about 80% of active users had typically masculine first names. However, that number declined to 48% as of June 2025, with active users slightly more likely to have typically feminine first names. Second, we find that nearly half of all messages sent by adults were sent by users under the age of 26, although age gaps have narrowed somewhat in recent months. Third, we find that ChatGPT usage has grown relatively faster in low- and middle-income countries over the last year. Fourth, we find that educated users and users in highly-paid professional occupations are substantially more likely to use ChatGPT for work.

We introduce a new taxonomy to classify messages according to the kind of output the user is seeking, using a simple rubric that we call Asking, Doing, or Expressing. Asking is when the user is seeking information or clarification to inform a decision, corresponding to problem-solving models of knowledge work… Doing is when the user wants to produce some output or perform a particular task, corresponding to classic task-based models of work… Expressing is when the user is expressing views or feelings but not seeking any information or action. We estimate that about 49% of messages are Asking, 40% are Doing, and 11% are Expressing. However, as of July 2025 about 56% of work-related messages are classified as Doing (e.g., performing job tasks), and nearly three-quarters of those are Writing tasks. The relative frequency of writing-related conversations is notable for two reasons. First, writing is a task that is common to nearly all white-collar jobs, and good written communication skills are among the top “soft” skills demanded by employers (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2024). Second, one distinctive feature of generative AI, relative to other information technologies, is its ability to produce long-form outputs such as writing and software code.

We also map message content to work activities using the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), a survey of job characteristics supported by the U.S. Department of Labor. We find that about 58% of work-related messages are associated with two broad work activities: 1) obtaining, documenting, and interpreting information; and 2) making decisions, giving advice, solving problems, and thinking creatively. Additionally, we find that the work activities associated with ChatGPT usage are highly similar across very different kinds of occupations. For example, the work activities Getting Information and Making Decisions and Solving Problems are in the top five of message frequency in nearly all occupations, ranging from management and business to STEM to administrative and sales occupations.

Overall, we find that information-seeking and decision support are the most common ChatGPT use cases in most jobs. This is consistent with the fact that almost half of all ChatGPT usage is either Practical Guidance or Seeking Information. We also show that Asking is growing faster than Doing, and that Asking messages are consistently rated as having higher quality both by a classifier that measures user satisfaction and from direct user feedback.

…We argue that ChatGPT likely improves worker output by providing decision support, which is especially important in knowledge-intensive jobs where better decision-making increases productivity (Deming, 2021; Caplin et al., 2023). This explains why Asking is relatively more common for educated users who are employed in highly-paid, professional occupations. Our findings are most consistent with Ide and Talamas (2025), who develop a model where AI agents can serve either as co-workers that produce output or as co-pilots that give advice and improve the productivity of human problem-solving.

Source & image: OpenAI

We tell ourselves the story of human uniqueness like a bedtime prayer

While I think this post overestimates the ‘rupture’ of AI, it is very well-written and certainly makes the reader think about the “clean arguments and messy implications” of “computation without consciousness” in a market which is a “sorting engine for outcomes.”

For me, though, the thing which is missing from this otherwise well-written piece is that human exceptionalism applies to everything we do. We are full of paradoxes: we keep some kinds of animals as pets and eat other ones. We talk about the wonder of Nature while destroying it. We see ourselves as separate to the natural order of things rather than part of it.

I find it interesting to see which people get worked up about AI. Writers and artists, for sure, as their livelihoods are on the line. But also, I would suggest (and separately) people who see humanity as somehow special and unique—without, necessarily, being able to describe what that uniqueness is.

The podcast episode I was listening to this morning on the philosophy of self-destruction is illustrative here. Georges Bataille a philosopher I’d never before heard of, argued that the thing that makes us unique is our tendency to self-destruction and sacrifice. What that means in relation to “the boundary between human value and human utility” I’ll leave for you to decide.

We tell ourselves the story of human uniqueness like a bedtime prayer. We are the animal that understands. We are the creature that feels. We are the author of meaning. Then the machines arrive with more memory than our institutions, more patience than our professions, and an ability to synthesise that makes much of our work look like the slow rearrangement of furniture. We retreat to consciousness and call it the final moat. Perhaps it is. The trouble is that markets do not pay for qualia. They pay for results. A system that can pass for understanding in most practical situations is enough to reprice our worth, even if it experiences nothing while doing so.

[…]

What makes the present rupture stranger [than previous ones] is not that tasks are being automated. That is an old trick. It is that the rungs we used to climb are melting away beneath our feet. The legal apprentice once learned by reading mountains of documents. The junior developer learned by slogging through bugs. The analyst learned by cleaning data until patterns flashed in the mind like weather. Now the entry work evaporates. A machine does it in minutes and does not complain. We congratulate ourselves on efficiency and then discover we have created an experience cliff. We are asking people to supervise work they were never allowed to do. Even the best intentioned upskilling will falter if the pipeline that produces intuition has been hollowed out. This cliff also suggests a remedy in simulated apprenticeship, a deliberate redesign of early careers where newcomers learn by validating and correcting machine output rather than by doing the drudgework the machine has removed. It is a shrewd answer, and it may be the only bridge we can build at speed.

[…]

Philosophy arrives, as it tends to, with clean arguments and messy implications. You can hold on to the view that computation without consciousness is never true understanding and still lose the economic game. You can be right about the inside of experience and wrong about the price of it. To be consoled by the thought that machines do not feel while they outpace us in most of the places society rewards is to win a metaphysical medal and find no one pays for medals. The market is not a seminar. It is a sorting engine for outcomes.

[…]

The line we have been defending is the boundary between human value and human utility, and we have treated them as if they were the same. We have been racing to remain useful because our institutions can only recognise worth through productivity and pay. A civilisation that automates most of its work must decide whether it will abandon people or invent a new grammar for dignity. We can reform education until the syllabi shine and still fail if graduation delivers people into a labour market that no longer needs them. We can preach lifelong learning as a secular catechism and still feel the hollowness if learning has nowhere meaningful to land.

Source: Hybrid Horizons

Image: Drew Beamer

Most people could read extra lines on eye test charts after using the drops

Part of growing older is realising things that happened to ‘old’ people now are happening to you. For example, the classic middle-age (pre-reading glasses) technique of moving a mobile phone or book further away so that you can focus on it properly.

I’ve noticed my wife, who is the same age as me, doing this—and recently, I’ve notice it can take me a second to focus, too. Unlike her, I wear contact lenses, so requiring reading glasses will mean some kind of varifocal solution. While multifocal contact lenses exist, I can imagine this approach would be much better.

Hundreds of millions of people worldwide have presbyopia, which is when the eyes find it difficult to focus on objects and text up close. Glasses or surgery can usually resolve the problem but many find wearing spectacles inconvenient and having an operation is not an option for everyone.

Now experts say the solution could be as simple as using eye drops twice a day.

A study presented on Sunday at the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS) in Copenhagen showed that most people could read extra lines on eye test charts after using the drops. The improvement was sustained for two years.

[…]

The drops contain pilocarpine, a drug that constricts the pupils and contracts the muscle that controls the shape of the eye’s lens to enable focus on objects at different distances, and diclofenac, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that reduces inflammation.

“Impressively, 99% of 148 patients in the 1% pilocarpine group reached optimal near vision and were able to read two or more extra lines.”

Source: The Guardian

Image: Blaz Photo

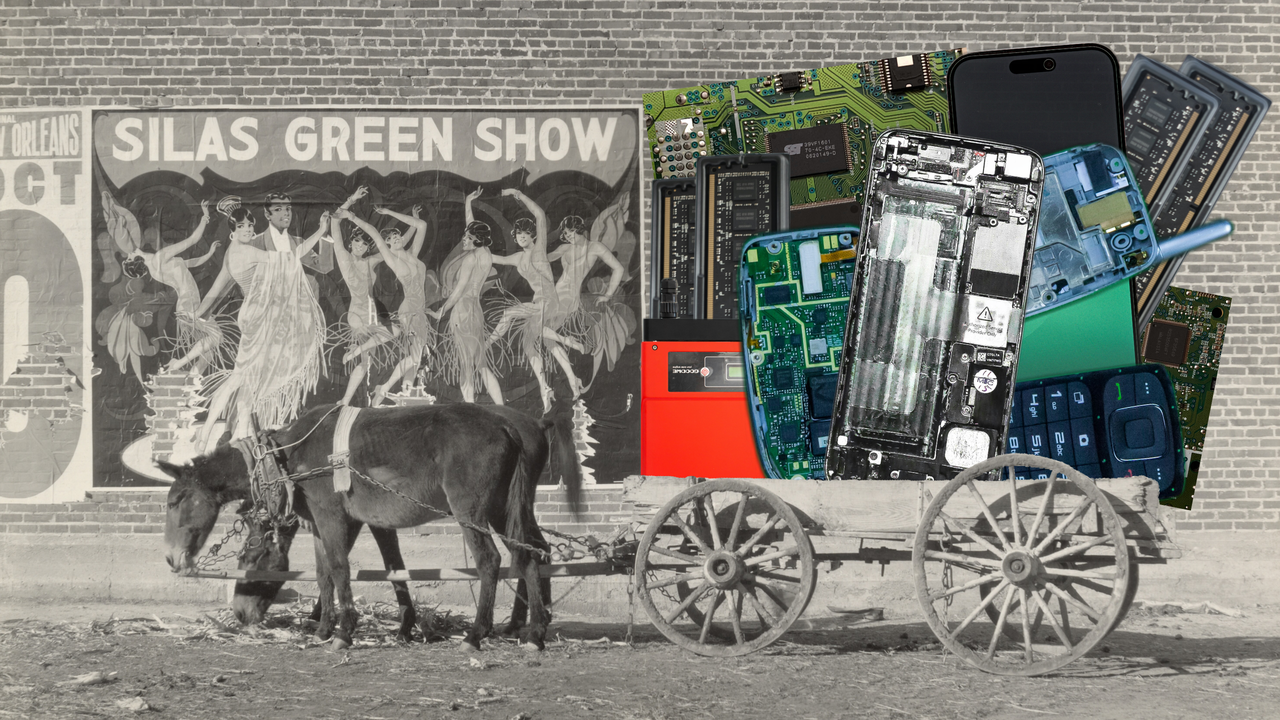

These images are made from open access sources, and they are themselves open access

For the last few years, in the time between Christmas and New Year, I’ve created a collage using issues of The Guardian Weekly and any other magazines I’ve found (example). Cory Doctorow, who makes everyone feel like an underperformer, creates one every day.

Thankfully, he also believes in open working and sharing, meaning we all get to use them under a permissive license) (in this case, CC BY-SA). He’s also collated his favourites into a limited-edition book. Because of course he has.

_ Canny Valley_ collects 80 of the best collages I’ve made for my Pluralistic newsletter, where I publish 5-6 essays every week, usually headed by a strange, humorous and/or grotesque image made up of public domain sources and Creative Commons works.

These images are made from open access sources, and they are themselves open access, licensed Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike, which means you can take them, remix them, even sell them, all without my permission.

I never thought I’d become a visual artist, but as I’ve grappled with the daily challenge of figuring out how to illustrate my furious editorials about contemporary techno-politics, especially “enshittification,” I’ve discovered a deep satisfaction from my deep dives into historical archives of illustration, and, of course, the remixing that comes afterward.

Source: Pluralistic

Image: CC BY-SA Cory Doctorow

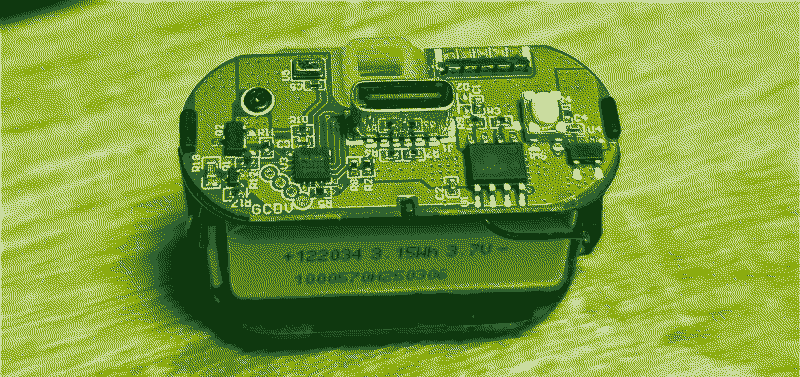

A 10y old phone can barely load google, and this is about 100x slower

If you visit dougbelshaw.com you will notice that the site loads instantly, no matter the speed of your connection or which device you’re on. That’s because it’s a mere 7.7kB in size. I did have it under 1kB, but I added a JavaScript effect, and a favicon.

That means that I could host this website on pretty much anything I choose — including, it turns out, a vape. That’s right, the microcontroller running inside a disposable vape is about the same clock speed as early 1990s personal computers. While they had more RAM and storage space, landfill considerations aside, it’s pretty incredible that someone has managed to run a website from things that are being used as fancy “pacifier for adults.”

I’m not here to scold anyone, but we’re so used to autoplaying videos these days, even on news sites, that we don’t question the impact that’s having on the energy consumption of the world. Combined with an increasing amount of dark data and perhaps it’s time to consciously minimise our digital footprints? Also, it’s cool to be able to host your website yourself on something like a vape. Much cooler than using them for their intended purpose!

For a couple of years now, I have been collecting disposable vapes from friends and family. Initially, I only salvaged the batteries for “future” projects (It’s not hoarding, I promise), but recently, disposable vapes have gotten more advanced. I wouldn’t want to be the lawyer who one day will have to argue how a device with USB C and a rechargeable battery can be classified as “disposable”. Thankfully, I don’t plan on pursuing law anytime soon.

Last year, I was tearing apart some of these fancier pacifiers for adults when I noticed something that caught my eye, instead of the expected black blob of goo hiding some ASIC (Application Specific Integrated Circuit) I see a little integrated circuit inscribed “PUYA”. I don’t blame you if this name doesn’t excite you as much it does me, most people have never heard of them. They are most well known for their flash chips, but I first came across them after reading Jay Carlson’s blog post about the cheapest flash microcontroller you can buy. They are quite capable little ARM Cortex-M0+ micros.

Over the past year I have collected quite a few of these PY32 based vapes, all of them from different models of vape from the same manufacturer. It’s not my place to do free advertising for big tobacco, so I won’t mention the brand I got it from, but if anyone who worked on designing them reads this, thanks for labeling the debug pins!

[…]

So here are the specs of a microcontroller so bad, it’s basically disposable:

- 24MHz Coretex M0+

- 24KiB of Flash Storage

- 3KiB of Static RAM

- a few peripherals, none of which we will use.

You may look at those specs and think that it’s not much to work with. I don’t blame you, a 10y old phone can barely load google, and this is about 100x slower. I on the other hand see a blazingly fast web server.

Source: BogdanTheGeek’s Blog

Image: modified from original included in source blog posts (using Dither It!)

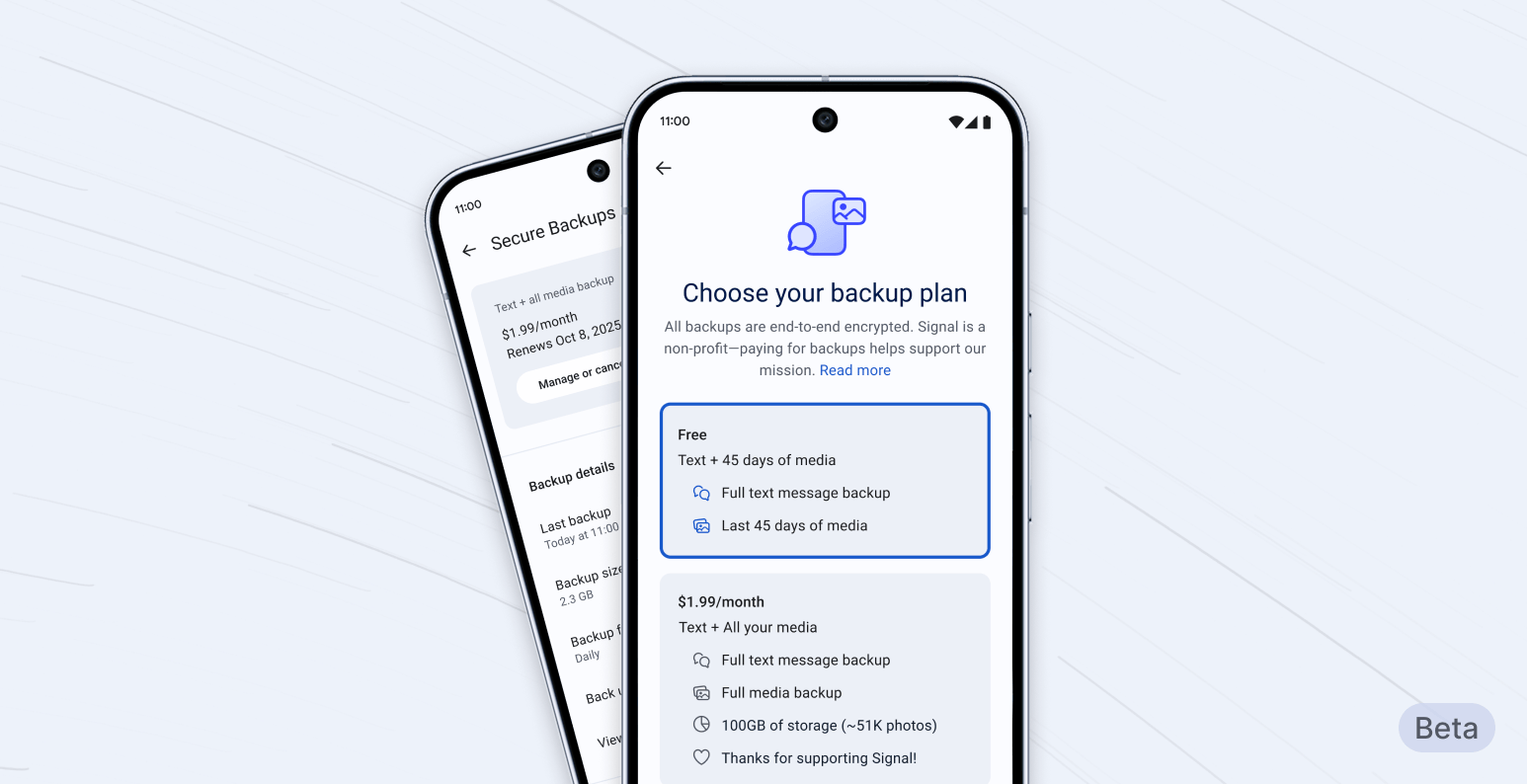

Secure backups let you save an archive of your Signal conversations in a privacy-preserving form

Recently, my Dad upgraded his iPhone and needed to move all of his apps from one phone to another. As anyone has done this will know, messages from encrypted messaging services such as WhatsApp and Signal usually have to be backed-up and then restored separately to the rest of the app transfer.

WhatsApp makes this easy, but much less secure, by allowing users to back up to Google Drive or iCloud. This is, by default, not encrypted, so it’s an easy vector for hackers and state-level actors to target. Signal, on the other hand, requires either device-to-device transfer of messages, or manual backup and restore.

Signal has just announced secure backups, which is a major step forward. After all, while you could regularly auto-backup Signal chats to local storage, if you lost or broke your phone, those messages were irretrievably lost.

After careful design and development, we are now starting to roll out secure backups, an opt-in feature. This first phase is available in the latest beta release for Android. This will let us further test this feature in a limited setting, before it rolls out to iOS and Desktop in the near future.

[…]

Secure backups let you save an archive of your Signal conversations in a privacy-preserving form, refreshed every day; giving you the ability to restore your chats even if you lose access to your phone. Signal’s secure backups are opt-in and, of course, end-to-end encrypted. So if you don’t want to create a secure backup archive of your Signal messages and media, you never have to use the feature.

[…]

This is the first time we’ve offered a paid feature. The reason we’re doing this is simple: media requires a lot of storage, and storing and transferring large amounts of data is expensive. As a nonprofit that refuses to collect or sell your data, Signal needs to cover those costs differently than other tech organizations that offer similar products but support themselves by selling ads and monetizing data.>

[…]

Once you’ve enabled secure backups, your device will automatically create a fresh secure backup archive every day, replacing the previous day’s archive. Only you can decrypt your backup archive, which will allow you to restore your message database (excluding view-once messages and messages scheduled to disappear within the next 24 hours). Because your secure backup archive is refreshed daily, anything you deleted in the past 24 hours, or any messages set to disappear are removed from the latest daily secure backup archive, as you intended.

Source & image: Signal blog

The FBI announced the alleged shooter’s apprehension with a quote from Mad Max

I’m not going to comment on the death of Charlie Kirk, but I would like to point to Garbage Day, the newsletter by Ryan Broderick which I quote regularly here on Thought Shrapnel. For me, it’s an essential aid to understand the world as it is today.

Another newsletter called Today in Tabs summarised the Garbage Day post I’m going to cite here the following way:

So in summary: it appears that this was a shooting where the victim, an influencer, was answering a question from another influencer when he was shot by a third influencer, after which a fourth influencer documented the ensuing chaos and a host of other influencers registered their takes, before the director of the FBI (an influencer) and the deputy director of the FBI (another influencer) announced the alleged shooter’s apprehension with a quote from Mad Max.

This is the way the world is today: confusing, and extremely online.

The Garbage Day post is therefore really useful and insightful. It explains terms such as “groyper” that I haven’t come across before and, as the father of an 18 year-old boy (man!), these are things it’s important to know about and discuss/share with teenagers. Well worth a read.

It’s also possible [suspect Tyler] Robinson genuinely believes in antifascist principles. But his alleged use of random internet brainrot is notable. Many extremism researchers this morning are wondering if Robinson is a self-identified “groyper,” or follower of far-right streamer Nick Fuentes. As we wrote yesterday, Fuentes has spent years attacking Kirk online. Groypers believed that Kirk was a sellout and blocking a much more extreme version of Trumpism from taking root. For years, Groypers have been carrying out what they call “Groyper Wars,” attending Kirk’s events and trying to disrupt them. For what it’s worth, 4chan users think Robinson was a Groyper.

Source: Garbage Day

Image: Steve Johnson

There's nothing they can do with the information

In general, there’s a difference between “being an informed citizen” and “being a news junkie.” Due to the fact that most people now get their ‘news’ via social media, and social networks are mostly algorithmic, there is often an emotional and/or partisan filter through which people obtain information. This is not good for our individual or collective mental health.

As a result, record numbers of people—including me— are limiting the amount of news they consume. Or at least how they consume it. I’ve even mostly stopped listening to The Rest is Politics, formerly one of my favourite podcasts. As this article points out, you have to be able to do something with the information you receive.

Globally, news avoidance is at a record high, according to an annual survey by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism published in June. This year, 40% of respondents, surveyed across nearly 50 countries, said they sometimes or often avoid the news, up from 29% in 2017 and the joint highest figure recorded.

The number was even higher in the US, at 42%, and in the UK, at 46%. Across markets, the top reason people gave for actively trying to avoid the news was that it negatively impacted their mood. Respondents also said they were worn out by the amount of news, that there is too much coverage of war and conflict, and that there’s nothing they can do with the information.

[…]

Studies suggest that increased exposure to news – particularly via television and social media, and especially coverage of tragic or distressing events – can take a toll on mental health.

[…]

A growing body of advice online promotes healthier ways to consume news. Much of it focuses on creating guardrails so people can be deliberate about finding information when they’re ready for it, instead of letting it reach them in a constant stream. This might include signing up for newsletters or summaries from trusted sources, turning off news alerts and limiting social media.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Buddy AN

99.9% of opinions on the internet don’t matter

Good stuff, as ever, from Jay Springett. He’s ostensibly talking about arguing on the internet, but this post is really about identity. Your identity might be reflected in the things you do or like, but this does not comprise the sum total of that identity.

Now, I get it, I totally do. I understand that when ones identity has been so completely ‘formatted’ by social platforms and consumer capitalism that an attack on a media property, tv show, album, podcast, game, book, football team or whatever, feels like an attack on your own identity as a person. One can’t help feel the need to go to war, to protect yourself. You aren’t the media you consume, and media properties aren’t your friends. Why argue or care about if genre fiction “is real literature” or not? I suspect its because people feel like they need validation for their choice of media diet? Validation for the amount of time and energy one has spent putting ones attention towards a certain interest. This need for validation results in people expressing their taste online, not by sharing what they love, but by fighting with someone who doesn’t.

[…]

There is a fundamental truth about the internet, and it also applies to building/having an audience: 99.9% of opinions on the internet don’t matter. You don’t know these people, and they don’t know you. Other peoples approval won’t keep you warm but the perceived lack of it will keep you awake at night. Their disapproval also shouldn’t stop you from loving the thing. You don’t need anyones approval to post on the internet, you can just do things, and like stuff.

The only people whose opinions really matter in this world are the ones expressed from across the table. From your family and friends over dinner. The people in your life who’ll ask your recommendations because they know that your taste is your own.

Source: thejaymo

Image: Kristaps Ungers

An open, decentralised protocol making clear to AI crawlers and agents the terms for licensing, usage, and compensation

Announced Wednesday morning, the “Really Simple Licensing” (RSL) standard evolves robots.txt instructions by adding an automated licensing layer that’s designed to block bots that don’t fairly compensate creators for content.

Free for any publisher to use starting today, the RSL standard is an open, decentralized protocol that makes clear to AI crawlers and agents the terms for licensing, usage, and compensation of any content used to train AI, a press release noted.

The standard was created by the RSL Collective, which was founded by Doug Leeds, former CEO of Ask.com, and Eckart Walther, a former Yahoo vice president of products and co-creator of the RSS standard, which made it easy to syndicate content across the web.

Based on the “Really Simple Syndication” (RSS) standard, RSL terms can be applied to protect any digital content, including webpages, books, videos, and datasets. The new standard supports “a range of licensing, usage, and royalty models, including free, attribution, subscription, pay-per-crawl (publishers get compensated every time an AI application crawls their content), and pay-per-inference (publishers get compensated every time an AI application uses their content to generate a response),” the press release said.

[…]

Eckart [Walther, co-creator of RSS] had watched the RSS standard quickly become adopted by millions of sites, and he realized that RSS had actually always been a licensing standard, Leeds said. Essentially, by adopting the RSS standard, publishers agreed to let search engines license a “bit” of their content in exchange for search traffic, and Eckart realized that it could be just as straightforward to add AI licensing terms in the same way. That way, publishers could strive to recapture lost search revenue by agreeing to license all or some part of their content to train AI in return for payment each time AI outputs link to their content.

Source: Ars Technica

Image: Leo Lau & Digit

Be intentional with how you spend your time, and realise you actually have a surprising amount of it

As quoted in The Marginalian, writer Annie Dillard famously stated “How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” The longer quotation, arguing in favour of adding structure and a schedule to your day goes like this:

How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time. A schedule is a mock-up of reason and order—willed, faked, and so brought into being; it is a peace and a haven set into the wreck of time; it is a lifeboat on which you find yourself, decades later, still living. Each day is the same, so you remember the series afterward as a blurred and powerful pattern.

Although he cites Tim Urban as an influence rather than Annie Dillard, this post by Nathan Brown makes a similar point. We have a finite amount of time on this earth, and finite number of hours available to us each week. A surprising number of these are discretionary—as in, whether it feels like it or not, we can choose how to use them.

I’m not a huge hustler. I’m not necessarily advocating that you spend your 52 hours/week building a startup or working an extra job. But I’m also an advocate for not being super lazy and sitting around and watching TikTok/YouTube all day.

I guess my point is to be intentional with how you spend your time, and to realize you actually have a surprising amount of it, once you account for all the essentials. What percentage of your discretionary time do you want to spend on…

- hanging out with friends

- bettering yourself

- outdoor activities

- volunteering

- creative expression (art, writing, etc.)

- entertainment

You choose—seriously. Not trying to guilt-trip you into anything. But I will be damned if I go through my life spending 10 of my discretionary hours/week watching Instagram Reels and then my gravestone says:

“Nathan was a kind, loving soul. His greatest achievement was watching 7,000,000 Instagram Reels.”

Source: Nathan Brown

Image: Resource Database

Grid-forming batteries will ultimately corner the stability market thanks to their inherent multifunctionality

As the UK moves steadily towards a fully-renewable future, one of the issues can be stabilising the power grid when electricity suddenly drops or spikes. Wind and solar energy can, after all, be unpredictable. Traditionally, fossil fuel power stations have helped with this stabilisation, but these are being shut down to cut emissions and fight climate change.

New ‘grid-scale’ batteries are being build which act like giant backup reservoirs for electricity. They store extra power when there’s a surplus (e.g. sunny days, windy nights) and then quickly release this to the grid whenever there’s an unexpected drop. As the battery doesn’t burn fuel or make pollution, it’s great for the environment, and the new technology is fast enough to fill the power gap nearly instantly.

Zenobē’s global director of network infrastructure, Semih Oztreves, predicts that grid-forming batteries will ultimately corner the stability market thanks to their inherent multifunctionality. While synchronous condensers mostly sit idle, waiting for a rare grid fault, Zenobē’s advanced batteries earn daily revenue by doing what most other storage sites do. For example, they arbitrage energy, absorbing power when it’s cheap and selling when supplies get tight.

But the short-circuit chops of grid-forming batteries haven’t yet faced a real-life test. Until then, doubts linger about whether transmission relays will respond appropriately to the inverters’ digitally defined surge of current. In a report last year for Australian grid operator Transgrid, one expert advised against overreliance on grid-forming inverters for short-circuit current, saying that it would carry “high to very high risk.” The utility later announced 10 synchronous condensers and 5 grid-forming batteries to bolster its grid.

Source & image: IEEE Spectrum