It's better than strapping clay crocodiles to people’s heads and praying for the best

As I have written about several times over the years, I am a migraineur. They have been with me all my adult life, and I can’t really remember what life was like without them. Preventative medication makes me drowsy, so along with some relieving triptans my only relief is rest.

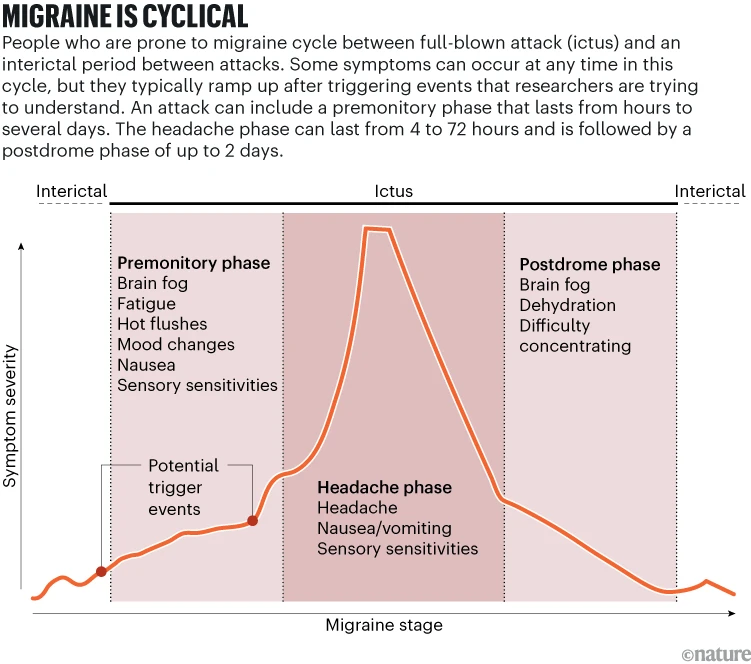

I’ve sent this article in Nature to my immediate family, who seem to confuse certain migraine phases with neurodiversity. The diagram below, in particular, is extremely valuable to anyone who is a migraineur, or who knows one. It’s easy to focus on the visual disturbances and the cranial pain, but there’s much more to it than that.

And, as I’ve discussed before, post-migraine is an extremely fertile time for me, with it being the perfect time for creative pursuits, including coming up with new or innovative ideas. That being said, I’m not entirely sure that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks, which is why I would absolutely explore new drugs which help prevent them in novel ways.

For ages, the perception of migraine has been one of suffering with little to no relief. In ancient Egypt, physicians strapped clay crocodiles to people’s heads and prayed for the best. And as late as the seventeenth century, surgeons bored holes into people’s skulls — some have suggested — to let the migraine out. The twentieth century brought much more effective treatments, but they did not work for a significant fraction of the roughly one billion people who experience migraine worldwide.

Now there is a new sense of progress running through the field, brought about by developments on several fronts. Medical advances in the past few decades — including the approval of gepants and related treatments — have redefined migraine as “a treatable and manageable condition”, says Diana Krause, a neuropharmacologist at the University of California, Irvine.

[…]

Researchers are trying to discover what triggers a migraine-prone brain to flip into a hyperactive state, causing a full-blown attack, or for that matter, what makes a brain prone to the condition. A new and broader approach to research and treatment is needed, says Arne May, a neurologist at the University Medical Center Hamburg–Eppendorf in Germany. To stop migraine completely and not just headache pain, he says, “we need to create new frameworks to understand how the brain activates the whole system of migraine”.

[…]

Researchers found that changes in the brain’s activity start appearing at what’s known as the premonitory phase, which begins hours to days before an attack (see ‘Migraine is cyclical’). The premonitory phase is characterized by a swathe of symptoms, including nausea, food cravings, faintness, fatigue and yawning. That’s often followed by a days-long migraine attack phase, which comes with overwhelming headache pain and other physical and psychological symptoms. After the attack subsides, the postdrome phase has its own associated set of symptoms that include depression, euphoria and fatigue. An interictal phase marks the time between attacks and can involve symptoms as well.

[…]

The limbic system is a group of interconnected brain structures that process sensory information and regulate emotions.. Studies that scanned the brains of people with migraine every few days for several weeks showed that hypothalamic connectivity to various parts of the brain increases just before a migraine attack begins, then collapses during the headache phase.

May and others think that the hypothalamus loses control over the limbic system about two days before the attack begins, and it results in changes to conscious experiences that might explain symptoms such as light- and sound-sensitivity, or cognitive impairments. At the same time, the breakdown of hypothalamic control puts the body’s homeostatic balance out of kilter, which explains why symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, yawning and food cravings are common when a migraine is building up, says Krause.

Migraine researchers now talk of a hypothetical ‘migraine threshold’ in which environmental or physiological triggers tip brain activity into a dysregulated state.

Source: Nature

Images: taken from the article