💥 Thought Shrapnel: 13th July 2025

A reminder that Thought Shrapnel is in low-power mode over the summer. I’m continuing share 10 things each week — but in a single post, with a tiny bit of commentary ☀️

- ZWO Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2025 shortlist (RMG) — The above image is entitled “Dragon Tree Trails” by Benjamin Barakat and it’s made up of 300 individual exposures. It’s one of a number of stunning issues on this shortlist.

- Artificial intelligence is the opposite of education (imperfect offerings) — Helen Beetham goes full hardcore mode against AI (by which I understand she means the sociotechnical system around generative AI). I hope she releases the podcast episode I recorded with her a few months ago soon!

- AI Can’t Take Over Soon Enough For Me. (Roving Dynamics Ltd) — Literally the opposite view to Helen, although not as eloquently stated. I’m somewhere in the middle of the two, ever since reading Fully Automated Luxury Communism.

- Jack Dorsey made an encrypted Bluetooth messaging app (The Verge) — In many ways, Bluetooth mesh messaging is nothing new (see Briar). However, bitchat adds end-to-end encryption, message encryption, battery optimisation, and other useful features. It’s already been ported to Android.

- 4.6 Billion Years On, the Sun Is Having a Moment (The New Yorker) — In a few weeks' time we’re getting as many solar panels installed Chez Belshaw as possible. This article explains why.

- The Mask-Off Moment for Digital Identity _(The New Design Congress) — This is the foreword to an upcoming report which sounds like it’s going to be dynamite. I work in the area of digital credentials, mainly to do with recognition but there is obviously quite a large digital identity component to all of that…

- Junior Roles Aren’t Going Away (In The AIrena) — I’d ordinarily have a lot to say about this but, largely, I agree with it. What you get out of generative AI is largely what you put into it. And that includes clarity of thought/intention.

- Stop making me log in to everything (Embedded) — I mean, the irony of having to login to read all of this article, but again I’ve thought a lot about this. Especially when AI companies are hoovering up the open web.

- You’re Not Wasting Time, You’re Wasting Your Life (Part 1) (Part 2) (The Daily Stoic) — Listen to both parts for context, as this conversation between Ryan Holiday and Rutger Bregman is fascinating. Part 2 is gold: Bregman talks about his book Moral Ambition and how the quotation attributed to Margaret Mead is absolutely true.

- No (Poetry Foundation) I’m not sure where I came across this article by Anne Boyer from 2017 but it is magnificent: “History is full of people who just didn’t. They said no thank you, turned away, ran away to the desert, stood on the streets in rags, lived in barrels, burned down their own houses, walked barefoot through town, killed their rapists, pushed away dinner, meditated into the light.”

👋 There we go! I’m still on the other end of the internet, so feel free to comment / hit reply on this, and let me know what resonated.

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 6th July 2025

Thought Shrapnel is going into low-power mode for a few weeks over the summer. Instead of posting nothing at all, I’ve decided to continue to share 10 things each week — but in a single post, with minimal commentary ☀️

- Text therapy: study finds couples who use emojis in text messages feel closer (The Guardian) — Makes sense to me! I went to a presentation once that called emoji the most significant visual language since hieroglyphics.

- On July 7, Gemini AI will access your WhatsApp and more. Learn how to disable it on Android. (Tuta) — I use AI on a regular basis, but I don’t want Google’s generative AI playing fast-and-loose with all of my data, thank you very much.

- AI spots deadly heart risk most doctors can’t see (ScienceDaily) — It looks like a combination of AI and human oversight of things like scan results is likely to be game-changing.

- Flounder Mode (Colossus Review) — I love this piece on Kevin Kelly, especially the parts about “illegible career paths” and having a “good day, most days”. Refreshing.

- Changing Assessment: How to Design Curriculum for Human Flourishing (Conrad Hughes) — This 120-page, CC-licensed book looks great and exactly what we need to redesign assessment in the age of AI.

- Ghost and WordPress announce deeper social web collaboration (PPC Land) — Long-form content on the Fediverse is becoming more popular. See also this announcement from Bonfire.

- Writing Code Was Never The Bottleneck (ordep.dev) — This post is about code, but the same is true for anything: producing content isn’t the bottleneck, it’s the “clear thinking, careful review, and thoughtful design” that takes time.

- Millions of websites to get ‘game-changing’ AI bot blocker (BBC News) — There’s an element of closing door after the horse has bolted to this, but Cloudflare is a major player and their “Pay Per Crawl” system could change things.

- Project Vend: Can Claude run a small shop? (And why does that matter?) (Anthropic) — Laughable. Read in conjunction with this and this.

- Your Voice, Your World, Your Connections — The Reclaim Open 2025 conference happens online from 4-6 November, with submissions (in the form of a blog post) due by August 30th. (Side note: I always love see illustrations by Bryan Mathers on Reclaim sites, having introduced him to Jim Groom almost a decade ago around a table in Barcelona which also included Audrey Watters. Fun times.)

👋 That’s it! Have a good week. I’m still around if you comment / hit reply on this, so let me know what resonates.

– Doug

Unfortunately, a further escalation of the already dismal curtailing of academic freedom in the US appears to be likely.

Most people know about the Internet Archive and its role in preserving the history of the web. Less well-known are archives such as Anna’s Archive and other ‘shadow libraries’. Yes, you can use shadow libraries to pirate books, but as it proudly states, it’s “The largest truly open library in human history.”

TIB — Technische Informationsbibliothek, or the Leibniz Information Centre for Science and Technology is Germany’s national library for engineering, technology, and the natural sciences. They’ve created a ‘dark archive’ of arXiv, which is a freely accessible online archive for scientfic preprints, i.e. publications of scientific works that have not yet (fully) been peer-reviewed. These pre-prints are important for researchers accessing the latest research results.

They are explicitly doing this due to the situation in the USA at the moment, which is a good reminder to us all that the way the world used to be is not the way it is now. We should both update our mental models of how things work, and act to protect the things we hold dear.

(Interestingly, the authors note that, until fairly recently, there were mirrors held elsewhere, but the advent of fast Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) meant that mirrors felt like an ‘overhead’ and ‘inefficient. It’s a good reminder that using so-called cloud-based services simply means having your data on somebody else’s computer…)

Research and science are international, hence we are speaking of international scientific communities. A service such as arXiv might be operated by a US-based institution, Cornell University, but arXiv is being used by researchers worldwide, as, e.g., impressively evidenced by the submission statistics. Moreover, since the introduction of arXiv Membership in 2010, the funding of arXiv has been partially internationalised. TIB funds the German contribution, together with the Helmholtz Associaton of German Research Centres (HGF) und the Max Planck Society (MPG).

So when the Trump administration makes decisions that have fatal consequences for science and research in the US, the repercussions reach far beyond the Gulf of Mexico: Over the last days, reports are mounting in German media that attest to researchers not only fearing the loss of data , but also the loss of established information portals such as PubMed.

[…]

Unfortunately, a further escalation of the already dismal curtailing of academic freedom in the US appears to be likely. Not at least due to the great importance of US institutions in the international academic system, these developments affect research infrastructures worldwide. As ”Safeguarding Research and Culture” are writing in their mission statement, this warrants a change of mind, among other things towards more decentralised and thus more resilient infrastructures.

It’s worth noting that the current mirror / backup isn’t public:

The data are being stored, but if push comes to shove it would need some more steps to make them publicly available. Because a database service is much more than a mere backup copy of the data: Operating a productive user-facing service not only needs technical resources, but first and foremost a committed team which in the background takes care of diverse aspects such as quality assurance, content curation, or (technical) development.

Source: TIB blog

Image: David Pupăză

Free, customisable exemplar badges to support consistent, credible recognition of skills and learning across the UK.

I’m loath to be critical of efforts to encourage the use of badging in the UK, but this guide from the Digital Badge Commission is partying like it’s 2019 🫤

The response to my criticism will, no doubt, be that they’re trying to keep things “simple”. Having worked in many of the sectors targeted by these exemplar badges I think the examples are both out of date and, well… just not useful.

What do I mean?

- Schools: “Responsive student” badge which is essentially rewarding compliance.

- Higher Education: “Law Clinic Volunteer” badge which apparently aligns with the “Staying Positive” part of the Skills Builder framework(?)

- Vocational Skills: “Health and Safety Practitioner (ISO 45001:2018)” badge which is the kind of thing that the BSI should be endorsing.

It’s all somewhat disappointing, especially as the point of Open Badges, as outlined in the 2012 Mozilla white paper, was to empower learners. This seems to be at odds with this set of exemplar badges.

I’ve also got lots of opinions about the talk of the need for ‘consistency’ going back to this post I wrote back in 2012(!) about what people mean when they talk about “rigour.”

I’ve just been helping facilitate the Digital Credentials Consortium Summit over in The Netherlands which was a really forward-thinking space. The Open Badges standard is at v3, and aligns with the Verifiable Credentials data model. The Digital Badging Commission’s resources always feel behind the curve. Where’s the discussion of badge images being optional? Of digital wallets? Of the metadata fields introduced via VC-EDU? Sigh.

If you need a discussion based on up-to-date information and relevant examples, you know where I am.

The Digital Badging Commission has launched a suite of free, customisable exemplar badges to support consistent, credible recognition of skills and learning across the UK.

Developed in partnership with practitioners from education, employment, and community sectors, the 12 templates show how digital badges can be used in real-world settings – from schools and colleges to volunteering, the arts and the workplace.

Source: Digital Badging Commission

Image: George Pagan III

People contribute in their free time. Gratitude is the least we can offer.

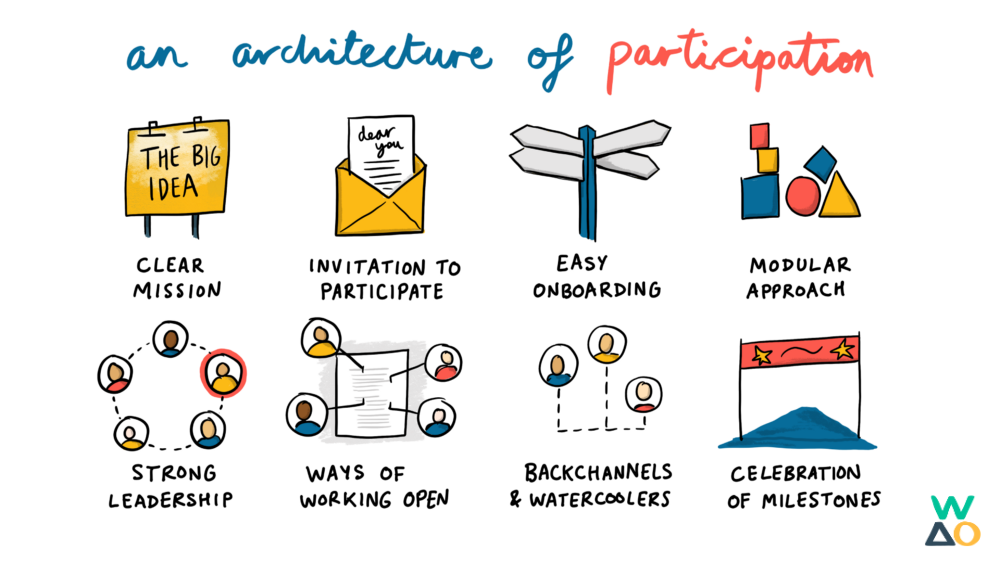

I’m sharing this resource primarily to bookmark it for future reference. It’s a fantastic introductory guide for those running Open Source projects on how to get more contributors — and keep them coming back.

Along with a clear mission, easy onboarding, and a modular approach (all parts of WAO’s Architecture of Participation shown above) the guide also talks about creating a place of generosity. I couldn’t agree more. There are lots of reasons why people contribute to Open Source software but making them feel good and valuable is always important.

Be kind, friendly, and grateful. People contribute in their free time. Gratitude is the least we can offer. Kindness helps create a welcoming and respectful space. It also makes discussions and disagreements much smoother. Ideally, you want the community to be able to manage the project without needing you all the time. That starts with setting the tone.

Be as responsive as you can, but don’t expect contributors to match your speed. Some will only have time to work on weekends or late at night. If you also maintain your project in your spare time, you’ll have similar expectations. It’s okay that some PRs will take weeks (with some back and forth) before they can be merged. That’s just how open-source works sometimes.

Be ready to help. At first, you might feel like you’re losing time (“If I did it myself, it would be faster”), but that’s short-term thinking. In the medium term, if you build the right environment, people will come back, and you’ll get those valuable recurring contributors that make a project healthy.

Source: curqui-blog

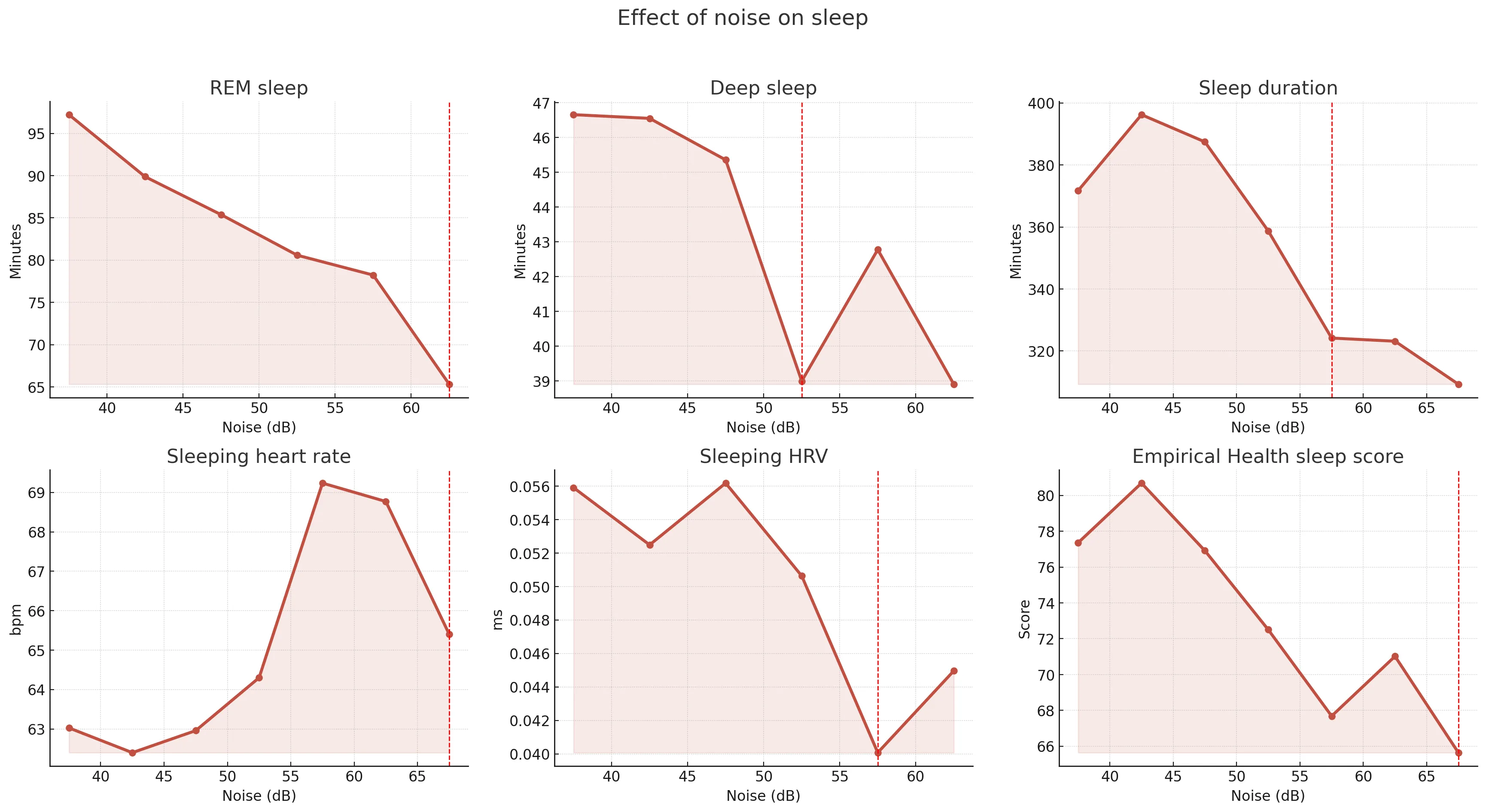

Keeping bedroom sound levels beneath the low-60s dB is a pivotal target for preserving restorative sleep stages

As someone whose sleep quality seemed to decline from my mid-thirties, I can understand the basis for this study. It doesn’t say how many people formed the ‘panel’ whose data was collected, but they found that sleep quality is affected over a certain decibel threshold.

The reason I’m sharing this is because about a year ago I bought a pair of sleep buds (I’ve actually got the discontinued Anker Soundcore A10’s) and it’s changed my life.

My understanding is that the noise it plays desensitises you to small noises outside that would otherwise wake you up. I’ve got mine set to turn off when I’ve been asleep for 30 minutes. So if, for example, you can’t keep bedroom sound levels “beneath the low-60s dB” all night, every night, then I’d encourage you to try some sleep buds.

Our panel shows a steady, almost linear erosion of REM minutes from the low-40 dB range through the mid-50s. Once noise climbs past roughly 58–60 dB (about the loudness of normal conversation), the line kinks sharply downward—REM time falls by an additional ~15 minutes in that single step. Deep-sleep minutes follow a similar pattern, holding fairly steady below 50 dB, slipping modestly through the low-50s, then dropping 6–7 minutes once the room crosses that same upper-50s threshold. Taken together, the curves suggest a threshold effect near 60 dB where restorative stages start to collapse rather than decline gradually.

[…]

The red dashed lines mark the single largest step-down for each series, and most of them cluster in a narrow band around 55–60 dB. Below that range, incremental quieting still buys modest gains, but above it the penalties accelerate: REM and deep minutes shrink by roughly a quarter, total sleep contract by about an hour, HR climbs by several beats per minute, and HRV flattens out.

Practically, that suggests a threshold effect: keeping bedroom sound levels beneath the low-60s dB (roughly the volume of normal conversation) is a pivotal target for preserving restorative sleep stages and the physiologic calm that goes with them.

Source: Empirical

People who can tolerate uncomfortable silences are typically better listeners

If you identify as male and are reading this, the chances are that you already know that you talk too much, or that you will learn that you do at some point in the future. This article, is therefore for you.

I still have a long way to go: although I don’t mean to, I interrupt people (especially women) and generally try and tell other people what is in my head. But I’m trying and I’m getting better at all of this. I also try and either explicitly or implicitly point out some of this to other men, while including women in conversations more.

At the end of the day, it’s about being interested in other people, not feeling like every silence has to be filled, and a room of n people, trying to ensure that you speak 1/nth of the time.

Men in public spaces, according to research, talk more than women, talk over women, and talk down to women, contributing to the rise of gender neologisms such as manologuing, bropropriating and mansplaining. So, aware that men tend to dominate and disrupt, aware that the world at large feels unbearably loud, aware that I, too, often add to that noise, I decided to learn to keep my mouth shut – starting in the general hellscape of social media.

[…]

I once live-tweeted my experience reading War and Peace just to show that I was the sort of person who read War and Peace. Life events fell victim to the social media lens. I could not simply enjoy Christmas or birthdays: I framed events in odd ways, repurposed them in pursuit of dopamine. “Books, booze and cherry blossoms,” I once tweeted, after workshopping the image and tagline with my partner on our anniversary. Nothing was sacred, nothing real, everything permitted.

[…]

Talking less in real life proved a tougher ordeal. My family are rough around the edges, my friends are on the wrong side of unruly: the people I love seldom get to finish sentences. I have often felt that my overtalking relied on the desire to be heard, a Darwinian survival of the loudest. But communication coach Weirong Li told me that the compulsion to talk often stems from the desire to escape silence. “Most people speak to avoid discomfort – not because they have something essential to say.” That rang true: the urge to avoid awkward silences has always felt urgent.

[…]

People who can tolerate uncomfortable silences are typically better listeners. Studies show that embracing awkward silences improves emotional self-regulation, fosters empathy and builds trust between conversational partners. I asked a friend, Makomborero Kasipo, a writer and registrar in psychiatry, to characterise my overtalking. “You talk to fill silence,” she said. “You express yourself, which is good, but then feel the need to defend what you have just expressed, then defend that against an imagined response, then apologise for talking too much, then apologise for apologising.” Mako offered advice: learn to feel comfortable in silence. “Develop the skill to let silence breathe.”

[…]

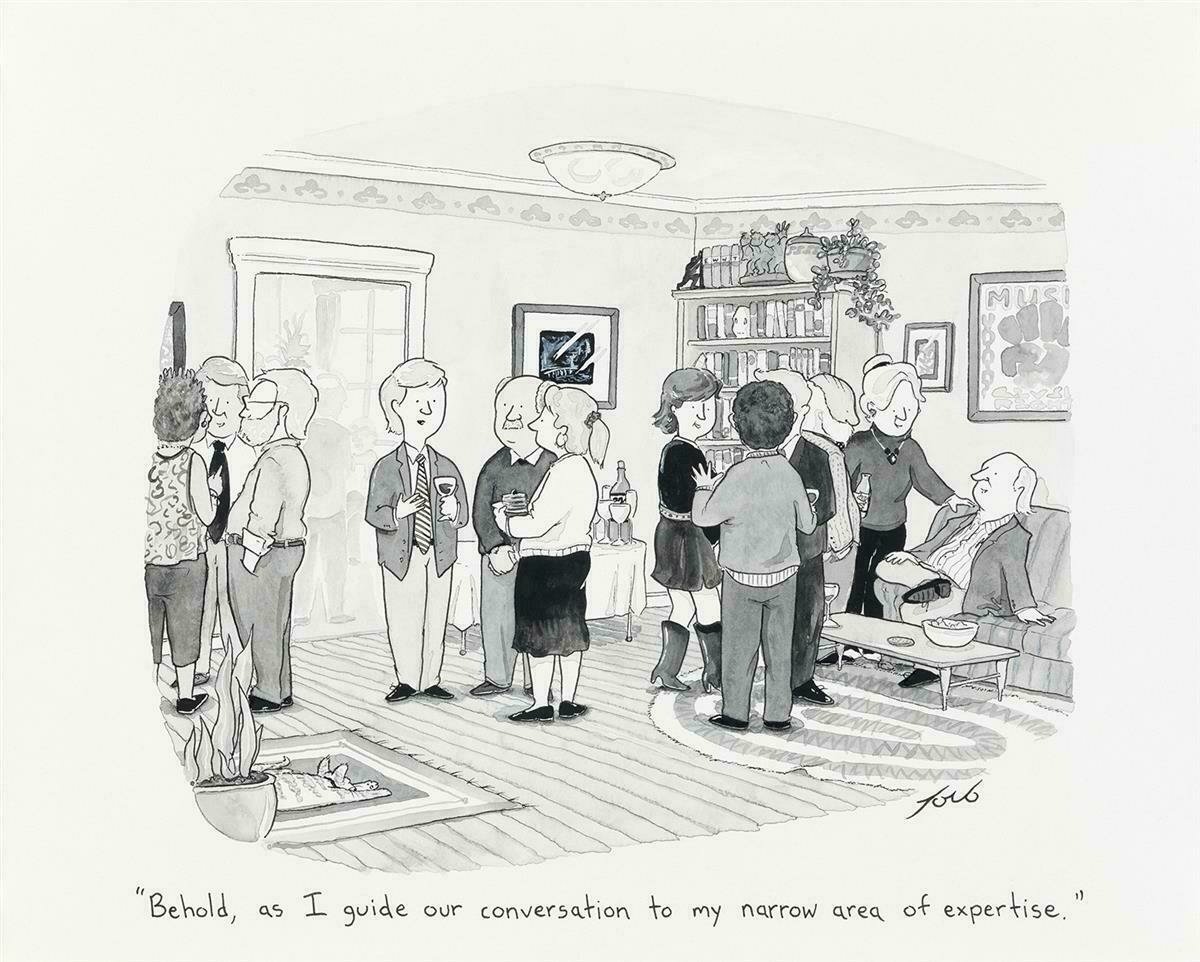

Talking less is not just about limiting the compulsion to talk. It’s also about changing the ways in which we converse. One of my main problems, according to my partner and any logical observer, was conversational narcissism: the art of bringing every discussion back to me. I’m very good at it. Most of us are. Sociologist Charles Derber recorded more than 100 dinner conversations and found two types of reaction: the support and the shift response. The support response is the lovely one, the bread and butter of therapists, the one that builds on the initial talker’s points and draws further discussion. A New Yorker cartoon depicts the bad response, the more common response, the shift response, as a man in a blazer at a dinner party says, “Behold, as I guide our conversation to my narrow area of expertise.”

[…]

Practise listening and you’ll stop talking. Active listening has become a buzzword, abused by droves of middle managers, corporate gurus and lifestyle coaches. Listening, to them, depends on the right sort of nod, mirrored questions and choreographed body language, always in pursuit of a goal: to make a sale, gain a promotion, secure a date, and so on. It is listening as performance. Emphasis remains on the outcome, not the process. But active listening, in its initial form, focuses on the talker. It is a skill that demands full attention, use of all the senses, the removal of obstacles to comprehension, and excavating meaning below intent.

Source: The Guardian

Image: The New Yorker

Is CC Signals the new robots.txt?

As Stephen Downes notes, Creative Commons (CC) has announced a new framework for signalling preferences around AI training. Building on an IETF draft standard, the idea is that creators can use machine-readable tags to express whether their work should be used for training AI, and if so, under what conditions.

Echoing the existing CC licenses, the ‘conditions’ might be providing credit to others, a financial contribution, or open-sourcing the resulting AI models. This all sounds well-intentioned, and you’d think I’d be in support of it. I’m a CC Fellow, after all. But instead, it feels out of touch with the reality of how large AI companies operate.

Stephen has already pointed out that this approach creates a pretend layer of control as CC Signals are not legally binding — and those with the most to gain from ignoring them are the least likely to pay attention. Our collective experience with robots.txt should probably serve as a warning for this: respect for voluntary signals only lasts as long as it suits the interests of those scraping the content.

Creative Commons licenses were created a couple of decades ago to allow creators to share their work openly and freely. CC Signals is attempting to protect creators, which is admirable, but makes the relationship transactional and so shifts CC away from its roots in open sharing. As the framework lacks any real mechanism for enforcement, there’s little to stop powerful actors from simply disregarding these preferences. It’s shutting the barn door after the horse has bolted.

TL;DR: technical standards are useful, but without legal backing or industry buy-in, this is little more than a polite request. I think the commons deserves more than a new version of robots.txt that can be ignored at scale.

Since the inception of CC, there have been two sides to the licenses. There’s the legal side, which describes in explicit and legally sound terms, what rights are granted for a particular item. But, equally there’s the social side, which is communicated when someone applies the CC icons. The icon acts as identification, a badge, a symbol that we are in this together, and that’s why we are sharing. Whether it’s scientific research, educational materials, or poetry, when it’s marked with a CC license it’s also accompanied by a social agreement which is anchored in reciprocity. This is for all of us.

[…]

Reciprocity in the age of AI means fostering a mutually beneficial relationship between creators/data stewards and AI model builders. For AI model builders who disproportionately benefit from the commons, reciprocity is a way of giving back to the commons that is community and context specific.

(And in case it wasn’t already clear, this piece isn’t about policy or laws, but about centering people).

Source: Creative Commons

"The music is one thing, but the message is a big part of why we’re getting across."

I’ve been listening to KNEECAP for the last couple of years since hearing one of their tracks on BBC 6 Music. And I really enjoyed the lightly fictionalised self-titled film of their origin story. But the best thing about them, I think, is how unashamedly political they are.

This has managed to get the trio (DJ Próvai, Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap) into a spot of bother, especially in the political climate where pointing out that Israel is carrying out a genocide against innocent Palestinians is, apparently, a controversial statement?

It’s always worth looking at who the establishment try to proscribe. Sometimes it’s because they’re speaking truth to power.

Israel has been carrying out a full-scale military campaign on occupied Gaza for almost two years, an onslaught triggered by Hamas’s 7 October 2023 attack on southern Israel, in which about 1,200 people were killed. The UN has found Israel’s military actions to be consistent with genocide, while Amnesty International and others have claimed Israel has shown an “intent to destroy” the Palestinian people. At least 56,000 Palestinians are now missing or dead, with studies at Yale and other universities suggesting the official tolls are being underestimated. (In July 2024, the Lancet medical journal estimated the true death toll at that point could be more than 186,000.) But away from Kneecap and other outspoken artists, across the creative industries as a whole relatively few have spoken about Gaza in such stark terms.

“The genocide in Palestine is a big reason we’re getting such big crowds at our gigs, because we are willing to put that message out there,” says Ó hAnnaidh. “Mainstream media has been trying to suppress that idea about the struggle in Palestine. People are looking at us as, I don’t know, a beacon of hope in some way – that this message will not be suppressed. The music is one thing, but the message is a big part of why we’re getting across.”

As working-class, early-career musicians, Kneecap have a lot more to lose by speaking out than more prominent artists, but Ó Cairealláin says this is beside the point. “You can get kind of bogged down talking about the people who aren’t talking enough or doing enough, but for us, it’s about talking about Palestine instead of pointing fingers,” he says. “There’s no doubt that there’s a lot of bands out there who could do a lot more, but hopefully just spreading awareness and being vocal and being unafraid will encourage them.”

Ó Dochartaigh adds: “We just want to stop people being murdered. There’s people starving to death, people being bombed every day. That’s the stuff we need to talk about, not fucking artists.”

There’s no doubt that Kneecap’s fearlessness when it comes to speaking about Palestine is a key part of their appeal for many: during a headline set at London’s Wide Awake festival last month, days after Ó hAnnaidh was charged for support of a terror organisation, an estimated 22,000 people chanted along with their calls of “free, free Palestine”. And thousands showed up to their Coachella sets – which the band allege is why so many pro-Israel groups were quick to push back on them, despite the fact that they had been displaying pro-Palestine messages for such a long time.

“We knew exactly that this was going to happen, maybe not to the extreme [level] that it has, but we knew that the Israeli lobbyists and the American government weren’t going to stand by idly while we spoke to thousands of young Americans who agree with us,” says Ó hAnnaidh. “They don’t want us coming to the American festivals, because they don’t want videos of young Americans chanting ‘free Palestine’ [even though] that is the actual belief in America. They just want to suppress it.”

The support for the message, says Ó Dochartaigh is “all genders, all religions, all colours, all creeds. Everybody knows what’s happening is wrong. You can’t even try to deny it now – Israel’s government is just acting with impunity and getting away with it. Us speaking out is a small detail – it’s the world’s governments that need to do something about it.”

Source: The Guardian

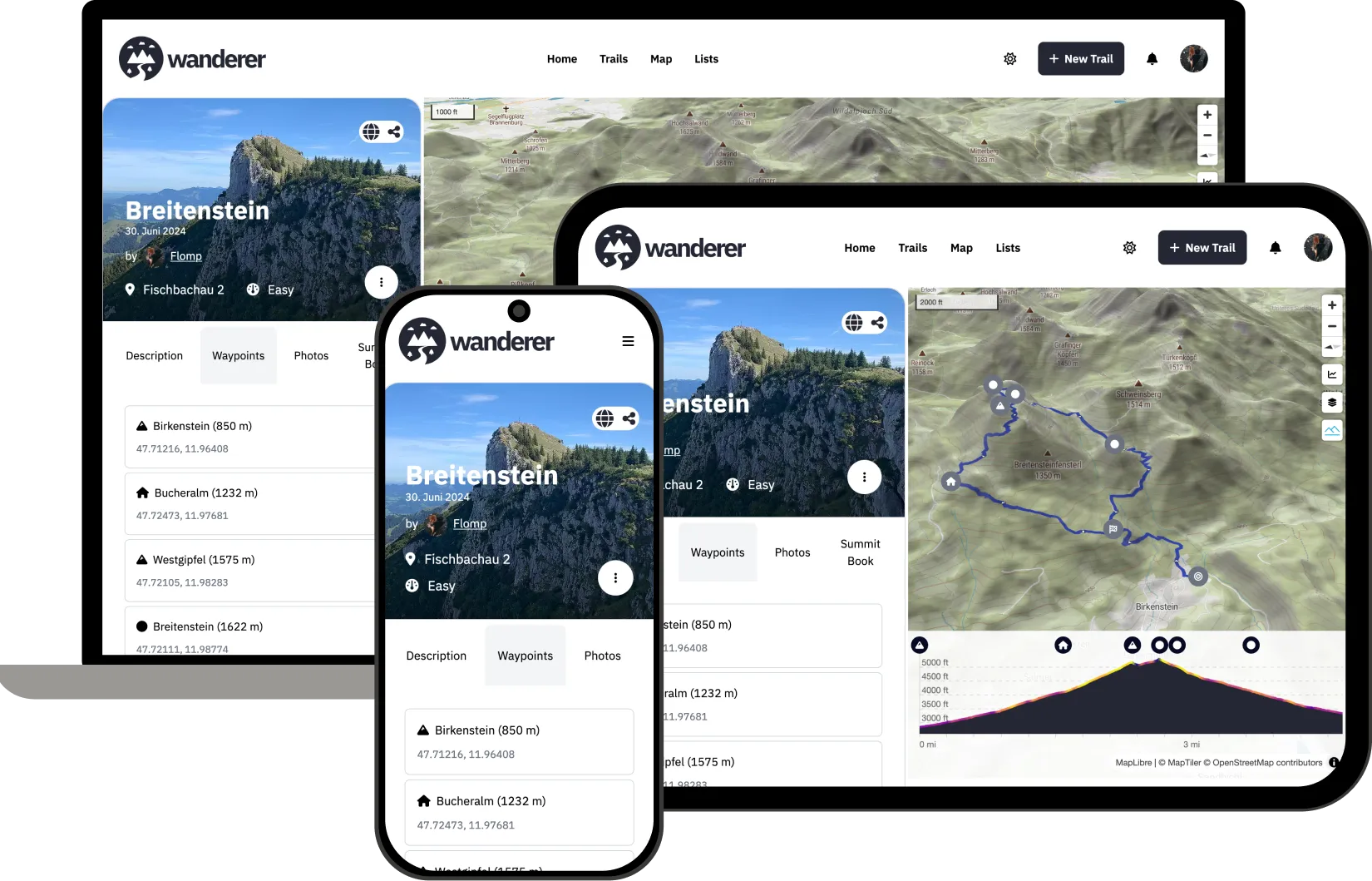

A decentralised, self-hosted trails database

Three years ago I created a Fediverse instance called exercise.cafe for discussion related to fitness and exercise. I handed that over a year later, realising that discussion without data wasn’t really much use in that context.

Thanks to the latest update which I discovered thanks to Laurens Hof, there’s a new option: wanderer. It’s a “self-hosted trails database” which the developer says now has the functionality to “follow users, comment, like, share trails, and more across instances.”

I can imagine groups of friends who go hiking together, running or cycling clubs, or all kinds of enthusiasts using this. It’s great news, and I’m looking forward to giving it a try.

wanderer is a decentralized, self-hosted trail database. You can upload your recorded GPS tracks or create new ones and add various metadata to build an easily searchable catalogue.

Whether you’re hiking through remote mountains or biking across the city, wanderer makes it easy to plan, record, and revisit your adventures. Draw new routes, upload GPS files, and access your trail data from any device — all while keeping full control over your data.

Already tracking your adventures with Komoot or Strava? wanderer makes it easy to bring your existing trail history with you. With built-in support for both platforms, you can import your routes and activities directly — no file conversions needed. Consolidate your outdoor journeys in one place, fully under your control.

wanderer isn’t just about trails — it’s about the people who share them. Follow other users to see their latest routes, like and comment on trails you love, and get notified when someone adds something new. Whether you’re part of a local hiking group or just discovering new paths, wanderer makes it easy to stay connected — across instances and platforms.

Source: wanderer

To retain any institutions of higher education in this onslaught from techno-authoritarianism requires – now and hereafter – we redesign them

As ever, there’s a lot in this post by Audrey Watters. Her depth of knowledge, range, and experience means that she packs a lot into this article. I haven’t excerpted the parts where she talks about AI because, although valuable, relevant, and insightful, I think that the AI “crisis” (if we can call it that) in Higher Education is largely one of its own making.

I, the product of several universities, am composing this an airport sipping a matcha latte, on my way to help facilitate an event around digital credentialing in Higher Education. There is, and always has been, an air of privilege around graduating from a university — especially an elite one. The experience of going away as (usually) an 18 year old, studying at a high(er) level, and experimenting with one’s identity cannot be reduced to the credential that comes at the end of one’s studies. As a signal, it’s not granular enough to be anything other than a proxy for reinforcing vibes, prejudice, and class.

This is why I’ve been so interested in Open Badges over the last 14 years. It’s a way of putting the “means of credentialing” into the hands of everybody — although, of course, it’s helped reinforce the power of some incumbents.

Back to the article, and Audrey says something with which I fundamentally agree, and which she puts with an elegance I could never muster: we need to be investing more in people than technology. The two aren’t mutually exclusive, of course, but what this means in practice is for universities to think about where they are investing their money. Just as we’re advising Amnesty International UK at the moment, you need to think really carefully about who controls the systems and data that you’re using to try and make the world a better place.

Back in 2012 (“the year of the MOOC”), when Sebastian Thrun told Wired that, in fifty years time there would only be ten universities left in the world and his startup Udacity had a chance to be one of them, I admit, I laughed. I laughed and laughed and laughed – mostly at the idea that Udacity would still be around in a decade let alone five. The startup, while never profitable or even, in the words of its own founder, any damn good, was hailed as a “tech unicorn” and valued at over a billion dollars… at least until it was acquired by Accenture last year for an undisclosed amount of money and folded into the latter’s AI teaching platform. So I’m pretty confident in saying that no, in fifty years time, Udacity will not be around.

But the question of whether or not there’ll be ten universities left in the world remains an open one, sadly, as the attacks on education have only grown in the past few years.

[…]

The Trump Administration, along with Silicon Valley, are fully committed to the destruction of higher education – the destruction of specific institutions to be sure (Harvard and Columbia, most obviously), but to the entire university project. What we are witnessing is an attack on public institutions certainly, but also on the whole idea of education as a public good. It is, as Adam Serwer argues in The Atlantic, an attack on knowledge itself.

To retain any institutions of higher education in this onslaught from techno-authoritarianism requires – now and hereafter – we redesign them, reorient them towards human knowledge and human flourishing, away from compliance and cowardice. This means quite literally an investment in humans, not in technology infrastructure – particularly not infrastructure owned and controlled by powerful monopolies, hell-bent on profiteering and extraction, hell-bent on creating a world in which we’re all drained of agency and autonomy and, above all, of the confidence in our own intelligence and capabilities. Building human capacity in schools requires supporting more teachers and researchers and librarians, not fewer – people whose understanding of information access, knowledge sharing, and knowledge development exists far, far beyond the systems sold to schools, systems that actually serve to circumscribe what we do and how we think; people who care about people, who care about knowledge as a collective good, who care about education as a core pillar of democracy, as practice of freedom not as a market, not as a credential.

Source: Second Breakfast

Image: Andrew MacDonald

We love these people because of what they left us. Not because of what they had.

Since writing the post I’m about to cite, the author has passed away. It was recommended to me by Bryan Alexander, someone who I have the privilege to say replies to my Thought Shrapnel digest every week. We have a little back and forth, and that’s it until the next weekend; it is from these small interactions that we weave our relationships and our lives.

The author of the post, Helen De Cruz, held the Danforth Chair in the Humanities at Saint Louis University. She was only a couple of years older than me, being born in 1978, but seemingly packed a lot into those years — including editing and illustrating Philosophy Illustrated: Forty-Two Thought Experiments to Broaden Your Mind. (Interestingly, I was using a book on the shelves in my home office called Philographics just yesterday to explain some philosophical concepts to my teenage daughter. Of course the first one she wanted explaining was epiphenomenalism 😅)

Helen wrote this post — her last — while receiving hospice care last month, saying that writing it took “days rather than just one morning or afternoon.” It’s funny how those about to die have moments of clarity that few of us manage in our lifetime. The title of the post, not unsurprisingly, is Can’t take it with you. What I like about it is that it expresses what Aristotle would have called _eudaimonia, that it is through our own flourishing that we contribute to the happiness of others.

The richest man on earth is not happy yet he can buy and do whatever he wants. When we cherish people of the past they were not particularly wealthy. Marie Curie, Vincent Van Gogh, our wise grandmother … we love these people because of what they left us. Not because of what they had.

[…]

At funerals and other occasions we also notice that we cherish others for their quirks. Someone, say a recently deceased can be remembered as kind and loving, but also: he loved fishing and was a great Cardinals fan. It seems puzzling that being a sports fan contributes to someone’s virtue. But it does, because that was part of what made him who he is. Mark Alfano has done systematic studies on this by looking at obituaries and they show that the surviving relatives seem to think being a sports fan is a virtue. As is being a dancer or birder.

Susan Wolf already remarked in Moral saints that a perfectly moral being who would always act to help others would be boring. Such a person would not have hobbies or quirks. It’s all time that could be spent better. Yet, somehow these are valued and we love them in others. This intuition bolsters the idea that having projects and passions can be a virtue. But how?

Audre Lorde and Spinoza helped me to see that being a good person means flourishing in many domains. Lorde saw herself as a poet foremost, as Caleb Ward explains in his monograph on Lorde (in progress). But she was also a Black woman, a mother, an activist, and a lesbian (“a woman who loves other women” as she called it). She insisted on being recognised in all her dimensions.

Spinoza counterintuitively argued for an ethical egoism in Ethics. He says we need to benefit ourselves. But our selves are in his picture finite expressions of God. And in our limited way, we can be perfect. Becoming very rich, powerful or prestigious is not benefiting yourself because these are empty goods in his view. This explains why the richest man on earth is not happy and keeps on seeking validation.

Pursuing empty goods of prestige, honor you become anxious because, for instance, prestige is dependent on what others think of you. It is exhausting, hence Spinoza decided that he didn’t care of what others thought of him. And we still value his work for that.

Instead, you benefit yourself by expressing yourself as a full being, as a rose bush that flowers fully. People also delight in you.

Source: Wondering Freely

Image: Raimond Klavins

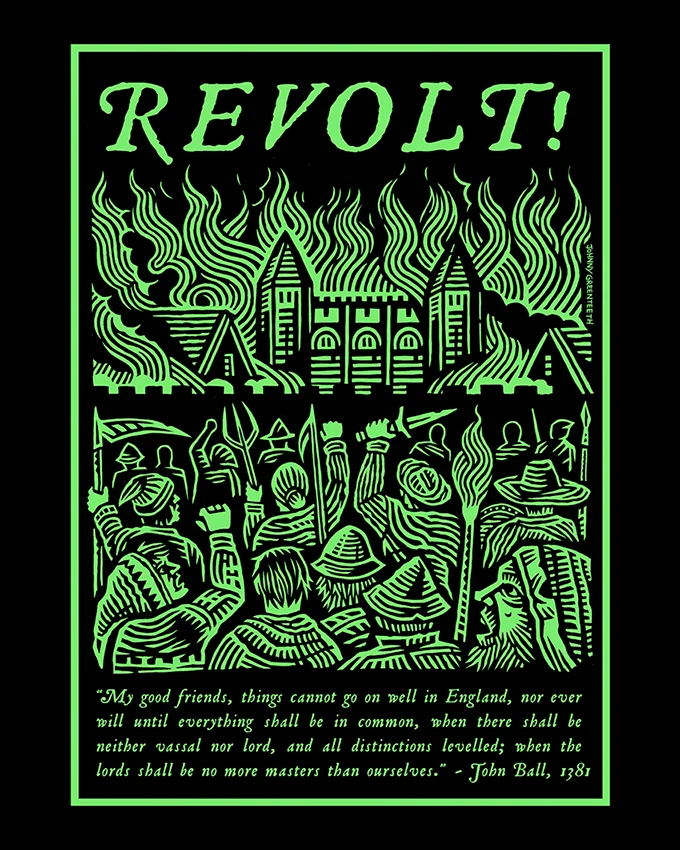

When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?

Sadly, this this poster was sold out and removed from Johnny Greenteeth’s store before I was ready to buy it. I wasn’t sure about it being DayGlo! But then, I remembered that episode of Frasier where he explains that his style is “eclectic” and if you have good stuff it just all goes together…

Discovered via Warren Ellis the text is from John Ball, priest and one of the leaders of the Peasant’s Revolt in England during 1381:

My good friends, things cannot go on well in England, nor ever will until everything shall be in common, when there shall be neither vassal nor lord, and all distinctions levelled; when the lords shall be no more masters than ourselves.

Ball was the one who famously said:

When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?

I think you can tell a lot about people by thinking about which side of the Peasant’s Revolt they would have been on. Also, if you’re interested in this sort of thing, and don’t already know about the times when England has been close to revolution, then I recommend also reading about the Levellers and the Diggers who were prominent during the English Civil Wars in the 17th century.

Signal groups make it possible to have semi-public, but still incredibly private, spaces

Just before composing this post, I created a Signal group for an upcoming event. Signal is my standard way to communicate with other people because it’s encrypted and not controlled by a Big Tech organisation. Why wouldn’t you want your conversations to be private by default?

We’re working with Amnesty International UK at the moment on a new community platform. One of the things that we’ll be recommending is that they think not just about the community platform itself, but about the ecosystem and the stack of technologies used by activists. We’d recommend that Signal is part of this.

If you’re new to Signal, especially if you operate in a sensitive context, you’ll find this post useful. The author, Micah Lee, has worked for the EFF and _The Intercept, he co-founded the Freedom of the Press Foundation, and develops tools like OnionShare and Dangerzone. He knows his stuff.

Signal groups, in particular, are more powerful than you might be aware of, even if you already use them all the time. In this post I’ll show you how to:

- Turn an in-person meeting into a Signal group using QR codes

- Manage large semi-public groups while still vetting new members

- Make announcement-only groups, perfect for volunteer networks rapidly responding to things like ICE raids

In particular, I appreciated the advice of how to set up semi-public group chats, but with vetting:

I’m in a Signal group with about 500 people from around the world that focuses on digital rights. I’ve known some people in the group for years, but others I’ve never met. Still, it’s a safe place to discuss human rights tech issues without worrying about infiltration by fascists.

The rules include, “Be cool and be kind, or be kicked out,” and “New members need to be vouched for by an existing member.” There are five admins. If I have a friend who I think would be good to add to the group, I can invite them, and then vouch for them in the group, and one of the admins can let them in. If someone tries joining and no one vouches for them, they don’t get let in.

Signal groups make it possible to have semi-public, but still incredibly private, spaces like this. If we want to grow movements, we need to welcome many, many more people. Everyone isn’t going to know and trust everyone else, so a simple rule like “you need an existing member to vouch for you” is a great way to keep out the riff-raff. You can always choose to make more strict rules if you want, like requiring two people to vouch for new members.

He also explains how to have an announcement-only Signal group which is useful for organising, linking to this article about Sunbird, “an anonymous, real-time announcement and coordination platform” which uses this feature.

Source: [micahflee](micahflee.com/using-sig…

Image: Mika Baumeister

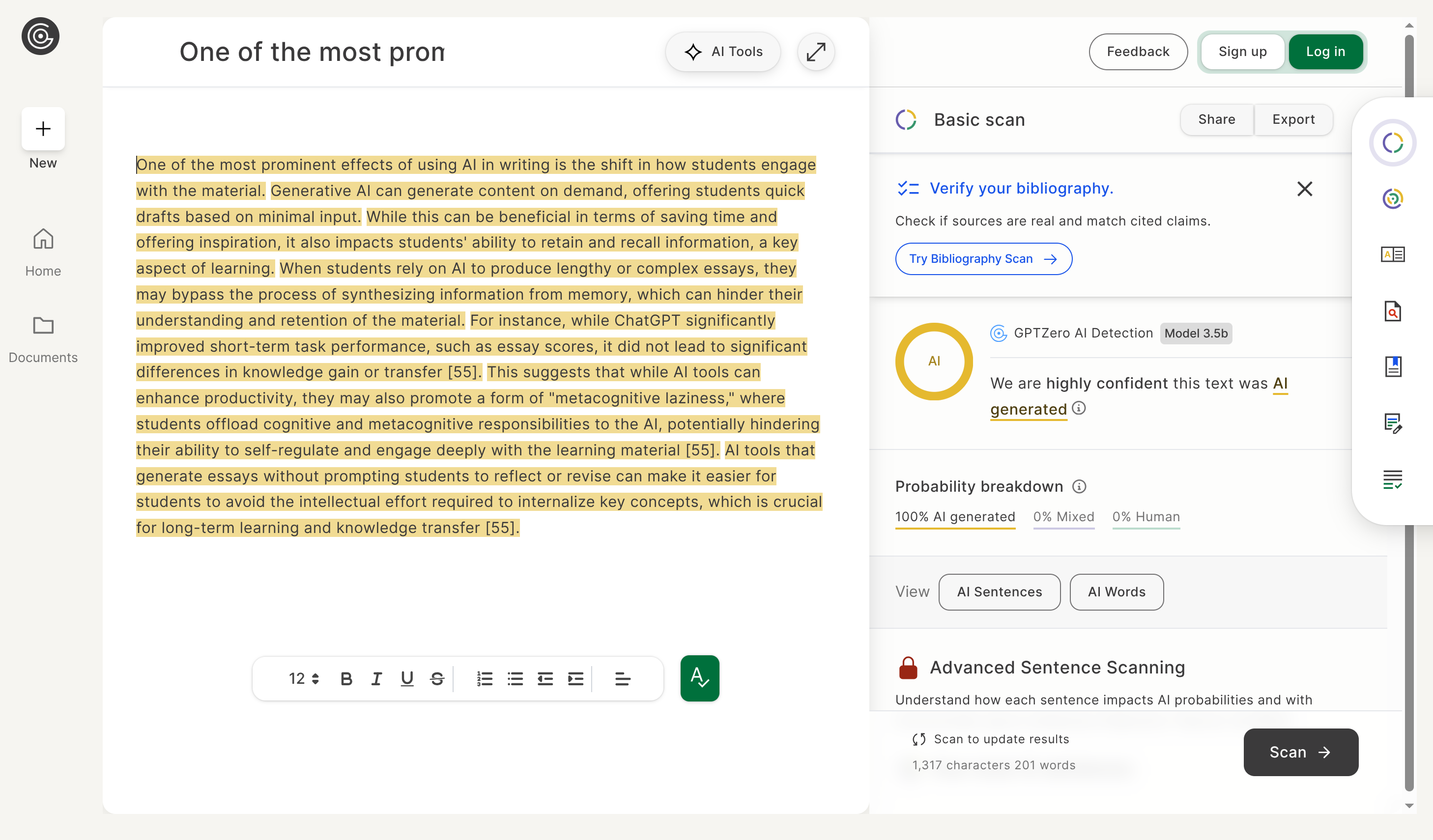

About that MIT paper on LLMs for essay writing...

I suppose I should say something about this MIT research about the use of LLMs for essay writing. I can guarantee you that most people who are using this paper to justify the position that “the use of LLMs is a bad thing” haven’t even read the proper abstract, never mind the full paper. There’s a lot of “news” about it, which mostly links to this press release.

So let’s actually look at the properly, shall we? We’ll start with part of the actual abstract from the academic paper:

We assigned participants to three groups: LLM group, Search Engine group, Brain-only group, where each participant used a designated tool (or no tool in the latter) to write an essay. We conducted 3 sessions with the same group assignment for each participant. In the 4th session we asked LLM group participants to use no tools (we refer to them as LLM-to-Brain), and the Brain-only group participants were asked to use LLM (Brain-to-LLM). We recruited a total of 54 participants for Sessions 1, 2, 3, and 18 participants among them completed session 4.

The 54 participants is a red herring, as the claims being made in this paper are based on the number of people who completed the fourth session — a total of 18 participants. Nine first used no tool, and then used an LLM (“Brain-to-LLM”) and first used an LLM and then no tool (“LLM-to-Brain”).

There’s lots of neuroscience in this paper which I’m not in a position to comment on. What I am in a position to comment on is the research design, the claims being made, and the language used to express them. The first thing I’d say is the press release being titled Your Brain on ChatGPT is purposely channeling the This Is Your Brain On Drugs commercial which aired in the US in the 1980s. I’m not sure that’s a very neutral framing.

Second, any time I see an uncritical reference to “Cognitive Load Theory” in an academic paper, it’s a huge red flag for me. As Alfie Kohn points out it’s usually a way of justifying direct instruction. In other words, centring the teacher instead of the learner.

Third, the paper is poorly organised and written. For example, if one of my GCSE students back in the day had written the following, I’d have underlined it in red and written “VAGUE” next to it:

Overall, the debate between search engines and LLMs is quite polarized and the new wave of LLMs is about to undoubtedly shape how people learn.

One of the funniest things about the paper, though, is that the authors undoubtedly used AI to write sections of it. For example, here’s a random paragraph (p.19)

So using LLMs is bad for essay-writing, but good for writing academic articles? Please.

I could continue. For example, the research design was terrible (a random collection of people with different levels of educational experience and qualifications), session 4 was optional, and the participants had 20 minutes to write an essay, in amongst other things. I mean, if someone gave you the following, pointed you at an LLM and gave you 20 minutes, what would you do?

Many people believe that loyalty whether to an individual, an organization, or a nation means unconditional and unquestioning support no matter what. To these people, the withdrawal of support is by definition a betrayal of loyalty. But doesn’t true loyalty sometimes require us to be critical of those we are loyal to? If we see that they are doing something that we believe is wrong, doesn’t true loyalty require us to speak up, even if we must be critical?

It’s not like they were being prompted to turn in an actual paper. Unlike the authors of this poor excuse for one.

Anyway, life is short and this paper is terrible. I’ll continue to use LLMs in my everyday work, and have zero issues with students using them to complete badly-designed assessment tasks. Final note: academics using LLMs (sometimes to write part of their papers!) while chiding students for doing so is abject hypocrisy.

Source: arXiv

Images: Growtika / Screenshot from GPTzero

Update: I just saw, via a link from Stephen Downes, a TIME Magazine article about this paper which says it hasn’t been peer reviewed. I missed that fact, and while the process isn’t infallible it explains a lot…

Misinformation and disinformation don’t actually need to convince anyone of anything to have an impact. They just need to make you question what you’re seeing.

Ryan Broderick is spot in this piece for Garbage Day about misinformation and disinformation. I do wonder why you’d want to continue using a service where you’re not quite sure what or who to believe. But then, I guess when most people are getting their news from social media, that is their information environment and questioning it might feel like questioning reality itself.

We live at a time where extremely high-resolution and extraordinarily detailed fake news can be generated almost instantly. But also, the threshold is (and always has been) extremely low for getting people to believe things — as the recent post about prompt injecting reality showed. When people spend so long online and don’t curate their own information environment, the habitus that guides their social actions can be actively dangerous.

You’d think the imminent breakdown of the global order would be worrying people more, but it’s hard to pay attention when you’re busy using AI to channel spirits and have ChatGPT-induced psychotic episodes. According to TikTokers, ChatGPT can “lift the veil between dimensions.” There’s also a guy on X who’s struggling to change the temperature of his AI-powered bed at the moment. The verified X user currently painting their roof blue to protect themselves from “direct energy weapons,” however, did not get the idea from an AI. They’re just the normal kind of internet insane.

[…]

It doesn’t matter if anyone believes the unreality of what they’re seeing online. Misinformation and disinformation don’t actually need to convince anyone of anything to have an impact. They just need to make you question what you’re seeing. The Big Lie and the millions of small ones online, whatever they happen to be wherever you’re living right now, just have to cause division. To wear you down. To provide an opening for those in power, who now have both too much of it and too few concerns about how to wield it. The populist demagogues and ravenous oligarchs the internet gave birth to in the 2010s are now firmly at the helm of the global order and, also, hooked up to the same chaotic, emotionally-gratifying global information networks that we all are, both social and, now, AI-generated. And, also like us, they are being heavily influenced by them in ways we can’t totally see or predict. Which is how we’ve ended up in a place where missiles are flying, planes are dropping out of the sky, and vulnerable people are being thrown in gulags, all while our leaders are shitposting about their big, beautiful plans for more extrajudicial arrests and genocidal territorial expansion. Assured by mindless AI chatbots that their dreams of world domination and self-enrichment are valid and noble and righteous. And there is no off ramp there. Everyone, even the folks with the nuclear codes, is entertaining themselves online as the world burns. Posting through it and monitoring the situation until it finally reaches their doorstep and forces them to look up from their phone and log off.

Source: Garbage Day

Image: Andrea De Santis

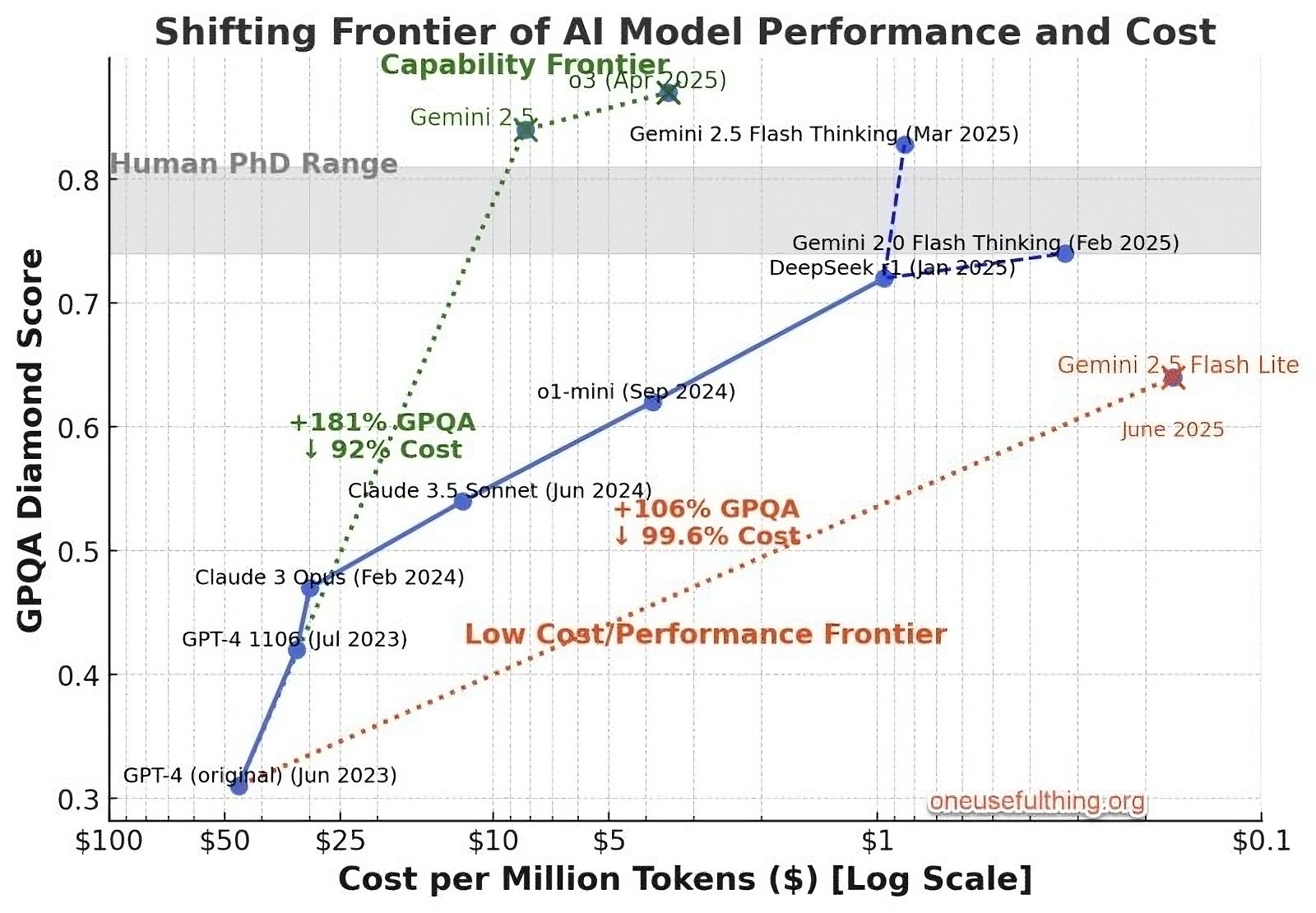

GPQA is difficult enough to be useful for scalable oversight research on future models significantly more capable than the best existing public models

The GPQA is “a challenging dataset of 448 multiple-choice questions written by domain experts in biology, physics, and chemistry” where even experts with unrestricted access to the web only reach 64% accuracy. It’s a benchmark used to rate generative AI models and, as Ethan Mollick notes using the chart he created above, they’re getting better at the GPQA even while the cost is coming down.

I used MiniMax Agent today, a new agentic AI webapp based on MiniMax-M1, “the world’s first open-source, large-scale, hybrid-attention reasoning model” according to the press release. It was impressive, both in terms of capability and flexibility of output. The kind of chain-of-reasoning it uses is going to be very useful to knowledge workers and researchers like me.

MiniMax-M1 is probably on a par with the ChatGPT o3 model, but of course it’s both Chinese and open source, so a direct competitor to OpenAI. I stopped using OpenAI’s products in January when it became clear that using them involved about the same level of associated cringe as driving a Tesla in 2025.

The questions are reasonably objective: experts achieve 65% accuracy, and many of their errors arise not from disagreement over the correct answer to the question, but mistakes due to the question’s sheer difficulty (when accounting for this conservatively, expert agreement is 74%). In contrast, our non-experts achieve only 34% accuracy, and GPT-4 with few-shot chain-of-thought prompting achieves 39%, where 25% accuracy is random chance. This confirms that GPQA is difficult enough to be useful for scalable oversight research on future models significantly more capable than the best existing public models.

Sources: arXiv & Ethan Mollick | LinkedIn

Our society is in the thrall of dumb management, and functions as such

It’s not easy to summarise this 13,000-word article by Ed Zitron, nor decide which parts to pull out and highlight. The main gist is that our economy is dominated by managers who lack real understanding of their businesses and customers. Their poor decisions are fueled by decades of neoliberal thinking, which promotes short-term gains over meaningful contributions. The name Zitron gives to these managers is “Business Idiots” who thrive on alienation and avoid accountability.

I think he’s using this term because ranting about rich people in an unequal society is pointless; most are desperately looking upwards trying to copy behaviours which might pull them out of the mire. Also, talking about “Big Tech” is meaningless, because it’s difficult for people to understand structures and systems. So, to personify things, Zitron uses “Business Idiots” to make his points. I don’t disagree with him, but it is an argument which lacks nuance, despite the number of words used and links sprinkled liberally amongst the paragraphs. What he’s really talking about, as he tends to, is generative AI.

Perhaps it’s easier to take some of the highlights I made of the article and rearrange them to make a bit more sense. I’m not saying that Zitron doesn’t make sense, just that, if I presented them in the order in which I highlighted them, they wouldn’t benefit from the structure of the entire article.

Let’s start here:

On some level, modern corporate power structures are a giant game of telephone where vibes beget further vibes, where managers only kind-of-sort-of understand what’s going on, and the more vague one’s understanding is, the more likely you are to lean toward what’s good, or easy, or makes you feel warm and fuzzy inside.

Zitron has an issue with managers within large, hierarchical, for-profit businesses. He talks about hiring being broken (something I’ve talked about a lot) but in a way which situates it with the “vibe-based structure” outlined above:

We live in a symbolic economy where we apply for jobs, writing CVs and cover letters to resemble a certain kind of hire, with our resume read by someone who doesn’t do or understand our job, but yet is responsible for determining whether we’re worthy of going to the next step of the hiring process. All this so that we might get an interview with a manager or executive who will decide whether they think we can do it. We are managed by people whose job is implicitly not to do work, but oversee it. We are, as children (and young adults), encouraged to aspire to become a manager or executive, to “own our own business,” to “have people that work for us,” and the terms of our society are, by default, that management is not a role you work at, so much as a position you hold — a figurehead that passes the buck and makes far more of them than you do.

[…]

It’s about “managing people,” and that can mean just about anything, but often means “who do I take credit from or pass blame to,” because modern management has been stripped of all meaning other than continually reinforcing power structures for the next manager up.

I don’t think this is a modern phenomenon. I think that someone reading this in, say, the 1960s, would recognise this problem. The issue is hierarchy. The issue is capitalism.

The difference is that we now live within a neoliberal world order. But, again, Zitron isn’t really saying anything new here when again, later in the article, talks about us living in a “symbolic society.” The situationists such as Guy Debord were talking about this decades ago. It has long been thus.

I believe this process has created a symbolic society — one where people are elevated not by any actual ability to do something or knowledge they may have, but by their ability to make the right noises and look the right way to get ahead. The power structures of modern society are run by business idiots — people that have learned enough to impress the people above them, because the business idiots have had power for decades. They have bred out true meritocracy or achievement or value-creation in favor of symbolic growth and superficial intelligence, because real work is hard, and there are so many of them in power they’ve all found a way to work together.

What has changed — and this why I prefer reading someone measured and insightful like Cory Doctorow — is that the policy environment has changed. This has enabled and encouraged what Zitron calls the “business idiot” to flourish.

Big companies build products sold by specious executives or managers to other specious executives, and thus the products themselves stop resembling things that solve problems so much as they resemble a solution. After all, the person buying it — at least at the scale of a public company — isn’t necessarily the recipient of the final product, so they too are trained (and selected) to make calls based on vibes.

[…]

Our society is in the thrall of dumb management, and functions as such. Every government, the top quarter of every org chart, features little Neros who, instead of battling the fire engulfing Rome, are sat in their palaces strumming an off-key version of “Wonderwall” on the lyre and grumbling about how the firefighters need to work harder, and maybe we could replace them with an LLM and a smart sprinkler system.

The reason that executives can move between the top echelons of society even after serial failure is because of regulatory capture and the resultant lack of punishment for white-collar crime. If we rinse-and-repeat this kind of behaviour enough, we end up with money moving to the top of society at the expense of the rest of us. Governments, frightened of the elites, impose austerity policies, enter “public-private partnerships” and otherwise indemnify rich people from the downsides of their speculation.

Our economy in the west is therefore one where the only real game in town is to create products and services for individuals and businesses with money. And because of the regulatory environment, these are not, by and large good companies that exist to promote human flourishing:

The Business Idiot’s economy is one built for other Business Idiots. They can only make things that sell to companies that must always be in flux — which is the preferred environment of the Business Idiot, because if they’re not perpetually starting new initiatives and jumping on new “innovations,” they’d actually have to interact with the underlying production of the company. As these men – and it’s almost almost men – gain more political power, this situation is only likely to get worse. “You should believe people when they tell you who they are,” is advice I’ve been given before. You should also believe people when they tell you what their version of a utopian future looks like. I’m not sure the general population’s vision is in line with that of tech billionaires: These people are antithetical to what’s good in the world, and their power deprives us of happiness, the ability to thrive, and honestly any true innovation. The Business Idiot thrives on alienation — on distancing themselves from the customer and the thing they consume, and in many ways from society itself. Mark Zuckerberg wants us to have fake friends, Sam Altman wants us to have fake colleagues, and an increasingly loud group of executives salivate at the idea of replacing us with a fake version of us that will make a shittier version of what we make for a customer that said executive doesn’t fucking care about.

They’re building products for other people that don’t interact with the real world. We are no longer their customers, and so, we’re worth even less than before — which, as is the case in a world dominated by shareholder supremacy, not all that much.

They do not exist to make us better — the Business Idiot doesn’t really care about the real world, or what you do, or who you are, or anything other than your contribution to their power and wealth. This is why so many squealing little middle managers look up to the Musks and Altmans of the world, because they see in them the same kind of specious corporate authoritarian, someone above work, and thinking, and knowledge.

[…]

These people don’t want to automate work, they want to automate existence. They fantasize about hitting a button and something happening, because experiencing — living! — is beneath them, or at least your lives and your wants and your joy are. They don’t want to plan their kids’ birthday parties. They don’t want to research things. They don’t value culture or art or beauty. They want to skip to the end, hit fast-forward on anything, because human struggle is for the poor or unworthy.

Meanwhile, of course, young people – and especially young men – are spending hours each day on social media platforms owned by these tech billionaires. Their algorithms valorise topics and ideas which promote various forms of alienation. I’m not particularly hopeful for the future, especially after reading articles like this.

But the thing is, I think that writers such as Zitron have a duty to spell out the kind of utopia that he thinks we should be striving for. As with other techno-critics, it’s all very well pointing out how terrible things and people are, but if this is what you are doing, you need to be explicit about your position. What do you stand for? It’s very easy to point and one thing after another saying “this is terrible,” “that person is awful,” “this is broken,” etc. What’s much harder is to argue and fight for a world where the things you dislike are fixed.

Source: Where’s Your Ed At

Image: Hoyoun Lee

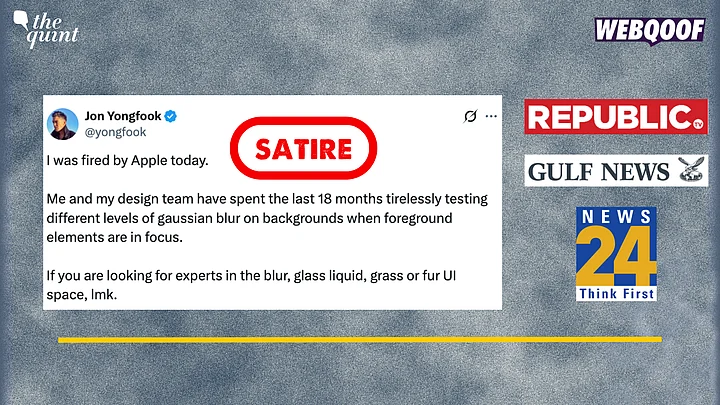

Prompt injecting reality

It’s easy to think that people who fall for misinformation are somehow stupid. However, a lot of what counts as ‘plausible’ information depends on the context in which its presented. Sending out a million fake ‘DHL has got your parcel and needs extra payment’ messages is successful to the scammer if 1% of recipients are expecting such a parcel. If 0.01% of the overall group click on the link, that’s still 100 people scammed.

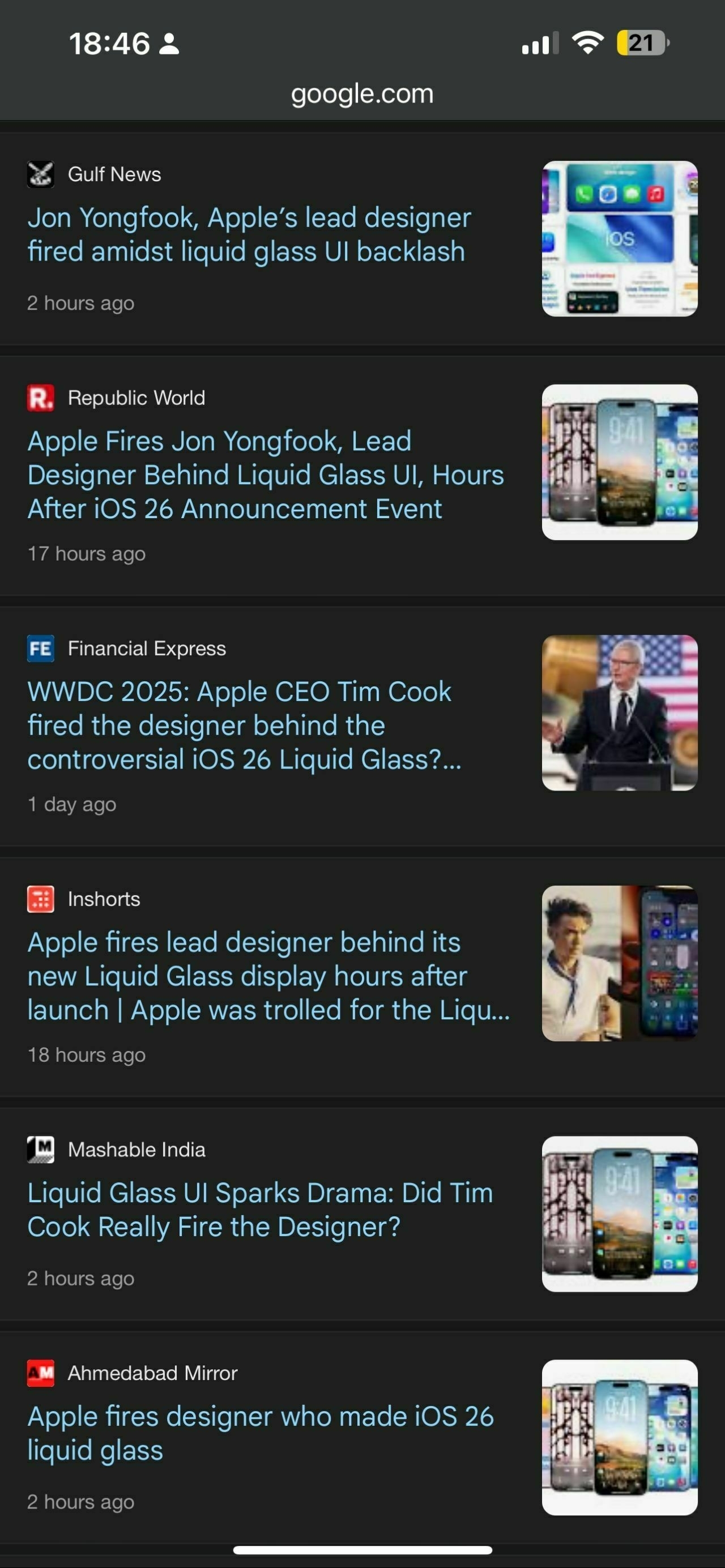

You may or may not have seen that there has been some ‘backlash’ about the design changes in iOS 26. The approach, named “Liquid Glass” has been criticised by accessibility and usability experts, which leads to this plausible-looking tweet:

Several news outlets reported on this as fact, meaning that Google News ended up looking like this (screenshot by Georg Zoeller:

Fake news, but with real consequences. Is Yongfook what he says he is? Of course not! (screenshot again by Georg Zoeller):

As I said many moons ago, our information environment is crucial to a flourishing democracy and civil society

Source: The Quint

Sandwich bags for cheese, blister plasters, and a 'bubble of pain'

There was a time, in the BuzzFeed era, where ‘listicles’ were everywhere. It seemed like everything was a list, and you couldn’t escape them. A decade or so later, we’re seeing more of a balance in the force, and so lists are useful rather than egregious.

This list in The Guardian is entitled ‘52 tiny annoying problems, solved!’ and I’d like to share a few of the suggestions which caught my eye.

I have a sandwich bag in my fridge of all the odds and ends of cheese; they keep for ages. I would always freeze feta, though, as it doesn’t last long. Likewise, keep any last little bits of carrot, onion or other veg in a bag and next time you are making a ragu or soup, chuck them in. If you buy a pot of cream for a recipe and use only a small amount, freeze the rest in an ice cube tray. Do the same with wine. GH

One idea I’ve found useful for dealing with irritating interruptions when you’re trying to concentrate is: be careful not to define more things than necessary as “interruptions”. If you’re the kind of person who tries to schedule your whole day very strictly, you’re pretty much asking to feel annoyed when reality collides with your rigid plan. If you have autonomy over your schedule, a better idea is to try to safeguard three or four hours at most for total focus – this is, it turns out, the maximum countless authors, scientists and artists have managed in an uninterrupted fashion anyway. If I’m working at home on a day when it’s not my turn for school pickup, and my son bursts in to tell me excitedly about something he’s done, it’s a shame if I feel annoyed by the intrusion rather than delighted by the serendipitous interaction, solely because I’ve defined that period as time for deep focus. OB

I discovered this by accident, but unsolicited door-knockers are eager to conclude their business and go away if you open the door while holding some kind of large electric gardening implement. I just happened to be carrying a hedge trimmer when the bell rang, but a chainsaw would be even better. You could leave it on a hook by the door. TD

Sooner or later, if you are running you will get a big bastard blister on your heel, and there is no point using anything other than one of those expensive padded blister plasters. Normal plasters won’t get you home without pain, or let you run again next day. PD

When someone has a minor injury, such as stubbing their toe, give them a full minute to themselves so they can enter, then exit, their “bubble of pain”. This is what we do in our family and I swear it helps get rid of pain much faster. We don’t ask, “What happened?” or, “Are you OK?” until the injured person speaks first. A hand on their shoulder or a respectful bowing of the head to the Gods of Minor Pain is sufficient at this time. Anonymous

May I just +1 the advice about blister plasters? If you’ve never used them, I don’t think you can possibly understand how much better they are than regular plasters. Next time you’re stocking up your first aid kid, consider buying some!

Source: The Guardian

Image: Seaview N.