People who can tolerate uncomfortable silences are typically better listeners

If you identify as male and are reading this, the chances are that you already know that you talk too much, or that you will learn that you do at some point in the future. This article, is therefore for you.

I still have a long way to go: although I don’t mean to, I interrupt people (especially women) and generally try and tell other people what is in my head. But I’m trying and I’m getting better at all of this. I also try and either explicitly or implicitly point out some of this to other men, while including women in conversations more.

At the end of the day, it’s about being interested in other people, not feeling like every silence has to be filled, and a room of n people, trying to ensure that you speak 1/nth of the time.

Men in public spaces, according to research, talk more than women, talk over women, and talk down to women, contributing to the rise of gender neologisms such as manologuing, bropropriating and mansplaining. So, aware that men tend to dominate and disrupt, aware that the world at large feels unbearably loud, aware that I, too, often add to that noise, I decided to learn to keep my mouth shut – starting in the general hellscape of social media.

[…]

I once live-tweeted my experience reading War and Peace just to show that I was the sort of person who read War and Peace. Life events fell victim to the social media lens. I could not simply enjoy Christmas or birthdays: I framed events in odd ways, repurposed them in pursuit of dopamine. “Books, booze and cherry blossoms,” I once tweeted, after workshopping the image and tagline with my partner on our anniversary. Nothing was sacred, nothing real, everything permitted.

[…]

Talking less in real life proved a tougher ordeal. My family are rough around the edges, my friends are on the wrong side of unruly: the people I love seldom get to finish sentences. I have often felt that my overtalking relied on the desire to be heard, a Darwinian survival of the loudest. But communication coach Weirong Li told me that the compulsion to talk often stems from the desire to escape silence. “Most people speak to avoid discomfort – not because they have something essential to say.” That rang true: the urge to avoid awkward silences has always felt urgent.

[…]

People who can tolerate uncomfortable silences are typically better listeners. Studies show that embracing awkward silences improves emotional self-regulation, fosters empathy and builds trust between conversational partners. I asked a friend, Makomborero Kasipo, a writer and registrar in psychiatry, to characterise my overtalking. “You talk to fill silence,” she said. “You express yourself, which is good, but then feel the need to defend what you have just expressed, then defend that against an imagined response, then apologise for talking too much, then apologise for apologising.” Mako offered advice: learn to feel comfortable in silence. “Develop the skill to let silence breathe.”

[…]

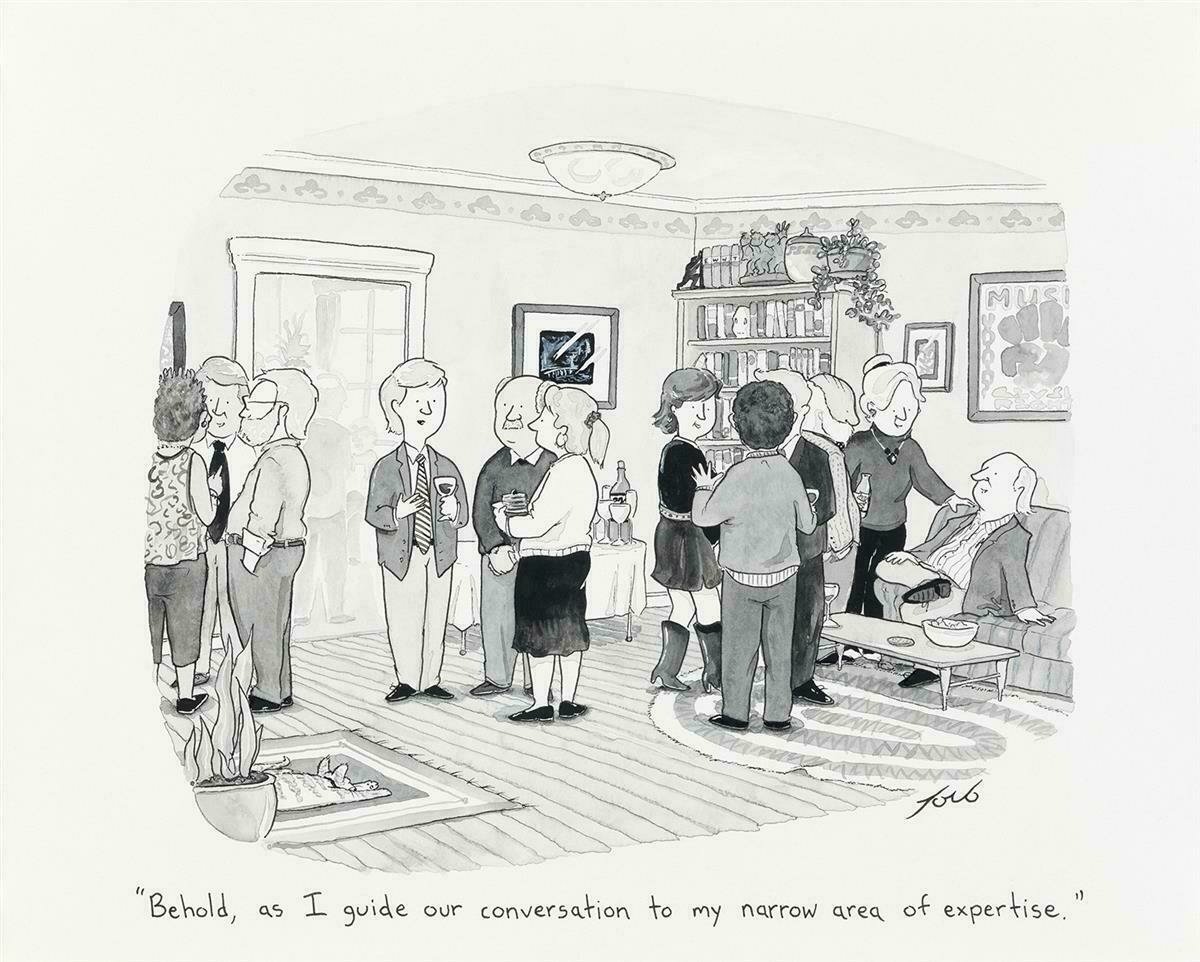

Talking less is not just about limiting the compulsion to talk. It’s also about changing the ways in which we converse. One of my main problems, according to my partner and any logical observer, was conversational narcissism: the art of bringing every discussion back to me. I’m very good at it. Most of us are. Sociologist Charles Derber recorded more than 100 dinner conversations and found two types of reaction: the support and the shift response. The support response is the lovely one, the bread and butter of therapists, the one that builds on the initial talker’s points and draws further discussion. A New Yorker cartoon depicts the bad response, the more common response, the shift response, as a man in a blazer at a dinner party says, “Behold, as I guide our conversation to my narrow area of expertise.”

[…]

Practise listening and you’ll stop talking. Active listening has become a buzzword, abused by droves of middle managers, corporate gurus and lifestyle coaches. Listening, to them, depends on the right sort of nod, mirrored questions and choreographed body language, always in pursuit of a goal: to make a sale, gain a promotion, secure a date, and so on. It is listening as performance. Emphasis remains on the outcome, not the process. But active listening, in its initial form, focuses on the talker. It is a skill that demands full attention, use of all the senses, the removal of obstacles to comprehension, and excavating meaning below intent.

Source: The Guardian

Image: The New Yorker