'Neom' is the sound of contractors being laid off

About 15 years ago, local residents where we used to live conned into backing (or at least not opposing) wind turbines being installed close to a residential area. The marketing materials included details of a proposed five-star hotel and golf course, which the developers said would help with tourism. Only the wind turbines were built, the developer “going bust” afterwards. I couldn’t stand the noise of the turbines, and it’s one of the reasons we moved.

It seems a similar kind of bait-and-switch is happening with the much-hyped Neom project in Saudi Arabia, a plan which I thought looked pretty dystopian in the launch video. I may be cynical, but perhaps they never intended to built it all? Perhaps it was meant to deflect attention away from their petro-checmical ambitions, sportswashing, and human rights abuses? It is a huge surprise to me that they built the luxury tourist destination part first. Huge.

Saudi Arabia has scaled back its medium-term ambitions for the desert development of Neom, the biggest project within Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s plans for diversifying the oil-dependent economy, according to people familiar with the matter.

By 2030, the government at one point hoped to have 1.5 million residents living in The Line, a sprawling, futuristic city it plans to contain within a pair of mirror-clad skyscrapers. Now, officials expect the development will house fewer than 300,000 residents by that time, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Officials have long said The Line would be built in stages and they expect it to ultimately cover a 170-kilometer stretch of desert along the coast. With the latest pullback, though, officials expect to have just 2.4 kilometers of the project completed by 2030, the person familiar with the matter said, who asked not to be named discussing non-public information.

Source: Bloomberg

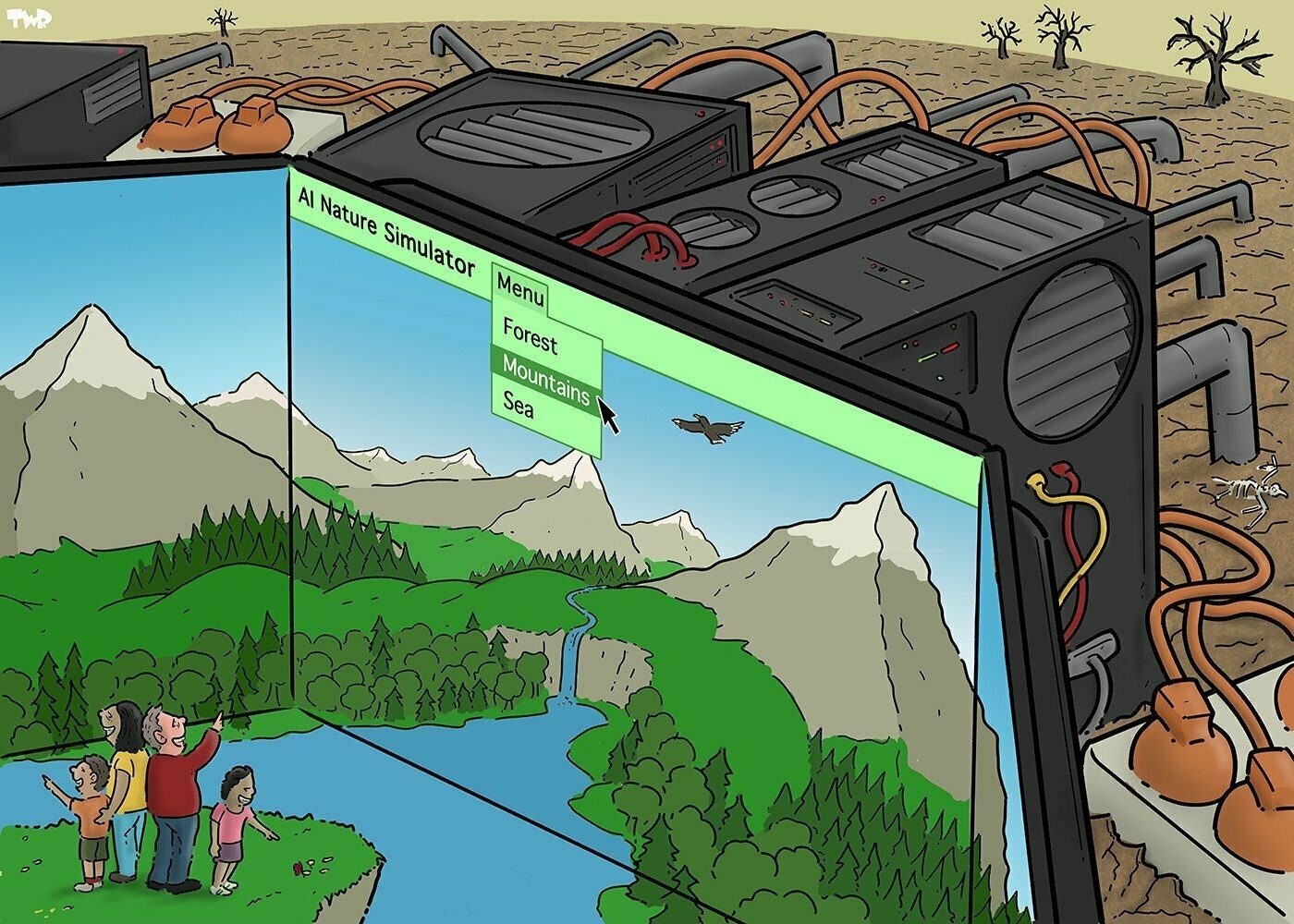

A tiny oasis of life, surrounded by an immensity of death

This cartoon is exactly the scenario I’m concerned about happening to the planet we call home. I’m going to juxtapose it with a quotation from William Shatner, the actor best known for his role in Star Trek and who finally got to go to space in 2021

Last year, at the age of 90, I had a life-changing experience. I went to space, after decades of playing a science-fiction character who was exploring the universe and building connections with many diverse life forms and cultures. I thought I would experience a similar feeling: a feeling of deep connection with the immensity around us, a deep call for endless exploration. A call to indeed boldly go where no one had gone before.

I was absolutely wrong. As I explained in my latest book, what I felt was totally different. I knew that many before me had experienced a greater sense of care while contemplating our planet from above, because they were struck by the apparent fragility of this suspended blue marble. I felt that too. But the strongest feeling, dominating everything else by far, was the deepest grief that I had ever experienced.

While I was looking away from Earth, and turned towards the rest of the universe, I didn’t feel connection; I didn’t feel attraction. What I understood, in the clearest possible way, was that we were living on a tiny oasis of life, surrounded by an immensity of death. I didn’t see infinite possibilities of worlds to explore, of adventures to have, or living creatures to connect with. I saw the deepest darkness I could have ever imagined, contrasting starkly with the welcoming warmth of our nurturing home planet.

This was an immensely powerful awakening for me. It filled me with sadness. I realised that we had spent decades, if not centuries, being obsessed with looking away, with looking outside. I played my part in popularising the idea that space was the final frontier. But I had to get to space to understand that Earth is, and will remain, our only home. And that we have been ravaging it, relentlessly, making it uninhabitable.

Image: Tjeerd Royaards

Text: The Guardian

Itano Circus

I can’t remember where I came across it, but I’ve bookmarked both a YouTube video and the Wikipedia article for the signature style of Japanese animator Ichirō Itano.

Not only is it awesome in its own right, I think I’m correct in saying that the person who mentioned it was using it as a metaphor for attacking something from multiple angles. Which is also fantastic.

Itano is best known among anime fans for a style of action scene that he developed, usually nicknamed “Itano Circus” (板野サーカス, Itano sākasu) or “Macross missile massacre” by fans; it refers to a highly stylized and acrobatic method of depicting aerial combat and dogfights in many anime, particularly the Macross series.

The battle scenes of the conventional mecha animation took the style of “duel” using guns and swords such as Western (genre) and Jidaigeki and there were many staging which emphasized the heaviness and posing (decision pose) of the robot. A good example of this is sword fight in battle scenes such as Gundam. He created new scenes with the acrobatic moves.

Source: Ichirō Itano

Gif from video: “It’s The Circus”

Football fan hierarchy

It remains a source of frustration to me that my kids support Liverpool. They’ve never been to a home game, and (I suspect) only chose them because they’re a good team in the Premier League, my wife being born there gave them an excuse, and my team (Sunderland) were doing terribly during their early years.

Of course, you can support whatever football team you like. But, as my mate Adam bangs on about all of the time, big money in football has corrupted the game.

[T]here are two concurrent developments taking place here. The first is the gradual realignment of fan hierarchy along the lines of one’s ability to pay: a development years in the making but now reaching a kind of tipping point amid rising prices and declining living standards. In his typically empathic and erudite way, Postecoglou was countering an argument that didn’t really exist. Nobody is discussing restricting access to foreign fans, who have always been able to rock up and buy a ticket. But in romanticising the devotion of the wealthy, amid price hikes that have enraged longstanding Spurs fans, Postecoglou offered up a justification that Daniel Levy and the corporate press office could scarcely have scripted more perfectly.

The other is the gradual erosion of the big club fanbase as a place of congregation and common ground. Broadening a fanbase also weakens it, weakens the ties that bind fans to each other, weakens their inclination to unite and organise. The mass of (mostly domestic-based) Manchester United fans resisting the sale of their club to a Qatari bidder were met by an equal and opposite wave of (mostly foreign-based) fans backing the Qatari bid. Meanwhile, how can we expect Chelsea fans to resist a future Super League if they can no longer even agree on whether Armando Broja is any good?

Source: The Guardian

Image: travis jones

De-bogging yourself

I’ll not do this often, and I obviously encourage you to read the original article, but here’s a GPT-4 summary of a fantastic post by Adam Mastroianni from the start of the year.

His topic is getting yourself out of a situation where you’re stuck, which he calls “de-bogging yourself”. I love the way he breaks it down into three different kinds of ‘bog phenomena’ and gives names to examples which fall into those categories.

Insufficient Activation Energy: Describes a lack of motivation to change, encompassing scenarios such as taking on unwanted projects (gutterballing), waiting for a perfect solution (waiting for jackpot), avoiding necessary actions out of fear (declining the dragon), and remaining in mediocre situations due to a lack of motivation to change (the mediocrity trap). Additionally, it covers obsessing over problems without seeking solutions (stroking the problem).

Bad Escape Plans: Details flawed strategies for change, including the belief that mere effort without direction will lead to improvement (the “try harder” fallacy), unrealistic expectations of future effort (the infinite effort illusion), blaming external factors (blaming God), misunderstanding the nature of problems (diploma vs. toothbrushing problems), expecting personal transformation without basis (fantastical metamorphosis), and attempting to control others' actions (puppeteering).

A Bog of One’s Own: Explores self-imposed psychological barriers to progress, such as overvaluing insignificant details (obsessing over tiny predictors) and holding unrealistic views of personal and others' problems (personal problems growth ray). It also discusses the detrimental effects of constant worry over external issues (super surveillance) and refusal to accept simple solutions (hedgehogging), culminating in the belief that personal satisfaction is unattainable (impossible satisfaction).

Source: Experimental History

Image: Maksim Shutov

The New York Times is a gaming platform

Via Garbage Day, this chart shows that The New York Times is more of a gaming platform than a news platform, in terms of time spent by visitors to their apps.

Remember when they bought Wordle? That was right at the end of January 2022 and here we are a couple of years later with games being a major driver of eyeballs on news sites.

This is inevitable, I guess, given that the majority of people get their news via headlines on social media, and that news sites increasingly have paywalls or login-gates. Still interesting though.

I am very excited about this chart because, as I wrote last month, The New York Times is a tech platform now, but, specifically, they’re a gaming platform. Which I always suspected would be the Next Big Thing in digital media and I’ve been desperate for example of how it would work.

You can track stages of internet development by the evolution of the web portal. And the biggest publishers tend to operate downstream and also mimic those portals. In the read-only age of AOL and Yahoo, you had static news sites. In the search and social age of Facebook and Google, you had aggregation and viral media. And the new age coming into focus right now is almost certainly led by interactive entertainment platforms. Entire ecosystems built around videos and games. And, like it or not, the next Pop Crave will be inside of Fortnite or, possibly, own their own version of it.

Source: Garbage Day

Borobudur

M.E. Rothwell’s Cosmographia is a frequent delight, and his latest missive really hits my sweet spot: an unknown history, a huge structure, and a bit of a mystery. I encourage you to go and read the whole thing, or at least just look at the wonderful illustrations.

Borobudur is the largest and most elaborate Buddhist temple in the entire world. Yet its origins remain a mystery.

The temple lies in central Java, Indonesia, surrounded by thick jungle and a ring of mountains. It’s suspected its construction, amid an area with no traces of any other ancient buildings, palaces, or cities, may have been begun by the Shailendra and/or Sanjaya dynasties of 8th century Java. It’s estimated one million stones, each weighing 100kg each, were mined from a nearby riverbed in order to build the stupa, which contains 504 statues of the Buddha and almost 3000 carved stone reliefs.

No one quite knows why such a vast Buddhist edifice was built in a primarily Hindu area, some 5000km away from the centre of Buddhist thought. It’s not even known what precise function it served. The sophisticated civilisation that birthed it went into a sudden and mysterious decline within a century of the temple’s completion in the mid-9th century.

[…]

[T]he temple was ‘rediscovered’ by the man with the most British name of all time — Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles. As Governor General of the Dutch East Indies between 1811 and 1816, Raffles took great interest in the history of the island. After he heard about the existence of a huge monument deep in the jungle, he dispatched Dutch engineer Hermann Cornelius to investigate. It took his team two months to cut back the undergrowth to reveal the extent of the huge temple complex.

Source: Cosmographia

Boundaries

I might pay for Noah Smith’s publication if it weren’t on Substack. While it’s a shame that I may never see the bit beyond the paywall of this article, there’s enough in the bit I can enough read to be thought-provoking.

He riffs off a Twitter thread by Mark Allan Bovair who points to 2015 when lots of people started to be extremely online. This changed society greatly because we started understanding the world through a political lens, both online and offline. (Although there isn’t really an ‘offline’ any more with smartphones in our pockets and wearables on our wrists.)

We like to think that our worldviews are based on facts, but they’re much more likely to be based on emotion. Given the increasingly-short social media-fueled news cycles, our tendency to favour images and video over text, and our willingness to share things that fit with our existing worldview, I think we’re in a lot of trouble, actually.

(I’d also point out in passing that the moral panic around teenagers and smartphones whipped up by commenters such as Jonathan Haidt says more about parents than it does about their kids)

Those equating this to events or technology are missing the point. There was a shift around 2015 where the “online” world spilled over into the real world and the way we view/treat each other changed.

After 2015 things in everyday life started to go through the political lens. We started to bucket people and behaviors along the political spectrum, which was largely an online behavior pre-2015. We started judging everyone as left or right, or we walked on eggshells to avoid it.

Before that, you knew your neighbor was Republican or Democrat based on their lawn signs, but it had little bearing on your daily interactions or behaviors. And it only seemed to matter every four years for a few months. Now it’s constant and pervasive.

And pre-2015 we had phones and social media, but there was more of a boundary, and most people would “log off” most of the day. The dopamine addiction, heightened by the polarization, was much lower. Only fringe message board and twitter posters spent their days arguing online, now it’s everywhere, and there’s no real boundary.

Source: Noahpinion

Eudaimonic exercise

Audrey Watters discusses “the yips,” a term for “a form of dissociative freeze” which is bound up with trauma and can lead to performance anxiety and failure.

I have nowhere near the level of trauma that Audrey has had in her life, but I certainly recognise the use of exercise and competition (with others / with self) as a way of not addressing certain things. For example, I’ve had some kind of virus over the last few days which has made me feel weak. I was desperate to get back to the gym.

Even without the personal grief, trauma, and baggage we carry around as we age, the pandemic means that we have a lot of collective issues to process. Exercise seems benign because it doesn’t seem destructive like, for example, drug use. But anything can be an addictive behaviour — and, as Aristotle pointed out, eudaimonia does not sit at an extreme.

I can troubleshoot what went wrong at the gym on Wednesday. I can troubleshoot why I’m having trouble getting back to the pace and distance I was running before my “accident.” I have a whole list of physiological reasons why the barbell’s not moving, why my legs are moving. My age. My training. My knee. My glutes. My diet. My sleep.

But I’m starting to recognize – really recognize – some significant psychological reasons too. My trauma. My trauma. My trauma. Not just my fall, but all the trauma that I’ve experienced in the last few years, last few decades. I’ve funneled a lot of my hopes for “mental health” into the rhythms of exercise and movement, and it’s an incredibly fragile routine.

There are times when I know my body loves it. And there are times when my brain certainly does too. But there are other times, particularly when I get the yips (which, for the record don’t always look like failing at a deadlift; it can be something that happens all the time, like failing to lean forward as I run) that I’m starting to recognize now are bound up in fear and shame.

I don’t think any amount of “tracking” or “optimization” with gadgets is going to address this issue. For me or for others. Indeed, what if we’re just making things worse?

Source: Second Breakfast

Origami unicorn

Erin Kissane wrote a long essay about Threads and the Fediverse. It’s worth a read in its own right, but the thing that really stood out to me for some reason was a random-ish link to instructions for making an origami unicorn.

There is zero chance of me ever making this, but I’m passing it on in case you’re less bad at this kind of thing. For me, it’s not the folding that I find difficult, it’s the rotational 3D stuff. I even find it difficult putting the duvet cover on the right way round (much to my wife’s amusement/dismay).

This model was first designed in 2014, but this is an updated version with some “bug fixes” (legs are properly locked) and a color changed horn.

Source: Jo Nakashima

The best antidote for the tendency to caricature one’s opponent

Daniel Dennett is a philosopher who I enjoyed reading an undergraduate studying towards a Philosophy degree. I don’t think I’ve read him since, although his book Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking is on my list of books I’d like to read.

Maria Popova has extracted four rules which Dennett cites in Intuition Pumps which originally come from game theorist Anatol Rapoport. Sounds like good advice to me, especially in this fractured, fragmented world.

How to compose a successful critical commentary:

You should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.”

You should list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement).

You should mention anything you have learned from your target.

Only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism.

Source: The Marginalian

Image: Daniel Dennett (via The New Yorker)

Endlessly clever

Ethan Marcotte takes a phrase used in passing by a friend and applies it to his own career. He makes a good point.

(I noticed that Marcotte’s logo resembles the Firefox imagery that was used while I was at Mozilla. I typed that organisation and his name into a search engine and serendipitiously discovered With Great Tech Comes Great Responsibility, which I don’t think I’ve seen before?)

As tech workers, we’re expected to constantly adapt — to be, well, endlessly clever. We’re asked to learn the latest framework, the newest design tool, the latest research methodology. Our tools keep getting updated, processes become more complex, and the simple act of just doing work seems to get redefined overnight.

And crucially, we’re not the ones who get to redefine how we work. Most recently, our industry’s relentless investment in “artificial intelligence” means that every time a new Devin or Firefly or Sora announces itself, the rest of us have to ask how we’ll adapt this time.

Dunno. Maybe it’s time we step out of that negotiation cycle, and start deciding what we want our work to look like.

Source: Ethan Marcotte

Image: Daniele Franchi

When should you replace running shoes?

John Sutton knows more about this area than I do. Not only his he an ultramarathon runner but he works in the area of ‘carbon literacy’ and sustainability. I’m also sure that he’s correct that the claims that you need to replace your running shoes after a certain number of miles is driven by marketing departments.

Still, I’ve definitely experienced creeping lower-back pain when getting to around 650 miles in a pair of running shoes. Of course, now I’m wondering whether it’s all psychosomatic…

With age and high mileage, it is said that the midsole no longer provides the cushioning that you need to prevent injury. This is cited as the main reason that shoes need replacing on a regular basis. Again, looking at the Lightboost midsole on these shoes, I see no evidence of crushing or squashing and I certainly don’t think I can feel any difference to the foot strike than when they were new. Obviously, any change in perceived cushioning is likely to be imperceptibly gradual and I could only really confirm that the cushioning was no longer up to snuff by comparing them directly with a new pair. These shoes are at a premium price (£170) and as such, I would expect them to be made of premium materials and built to last. My visual inspection of them suggests that they are still in excellent condition.

On the face of it, I see no obvious reason why I should retire these Ultraboost Lights any time soon. However, that seems to go against industry recommendations. What if invisible midsole damage has been so gradual that I haven’t noticed it? Now that I’ve reached 500 miles, am I likely to injure myself through continued usage? As a triathlete, I know from years of bitter experience that I am far more likely to injure myself on a run than I am cycling or swimming. So, anything I can do to improve my chances of not getting injured would be a powerful incentive to act. Thus, if it could be proven scientifically that buying a new pair of trainers every 300 – 500 miles would lessen my chances of injury, then I would take that evidence very seriously indeed.

[…]

In a previous blog post I discussed the carbon footprint of a pair of running shoes (usually between 8kg and 16kg of CO2 per pair). In the great scheme of things, this is not a huge figure (until you scale up to the billions pairs of trainers sold each year and the realisation that virtually all of these are destined for landfill at end of life). My Ultraboosts have a significant content made from ocean plastic and recycled plastic which reduces their carbon footprint by 10% compared to the previous model made with non-recycled materials. 10% is better than nothing, and the use of some ocean plastic is much better than taking plastic bottles out of the recycling loop and spinning them into polyester. But, I can do a lot better than 10% by not swapping my shoes for a new pair until they are properly worn out. Simply by deciding to double the mileage and aiming for at least 1000 miles out of these shoes (hopefully more) I can at least halve the carbon footprint of my running shoe consumption.

Source: Irontwit

Human agency in a world of AI

Dave White, Head of Digital Education and Academic Practice at the University of the Arts in London, reflects on a recent conference he attended where the tone seemed to be somewhat ‘defensive’. Instead of cheerleading for tech, the opening video and keynote instead focused on human agency.

White notes that this may be heartening but it’s a narrative that’s overly-simplistic. The creative process involves technology of all different types and descriptions. It’s not just the case that humans “get inspired” and then just use technology to achieve their ends.

The downside of these triangles is that they imply ‘development’ is a kind of ladder. You climb your way to the top where the best stuff happens. Anyone who has ever undertaken a creative process will know that it involves repeatedly moving up and down that ladder or rather, it involves iterating research, experimentation, analysis, reflection and creating (making). Every iteration is an authentic part of the process, every rung of the ladder is repeatedly required, so when I say technology allows us to spend more time at the ‘top’ of these diagrams, I’m not suggesting that we should try and avoid the rest.

I’d argue that attempting to erase the rest of the process with technology is missing the point(y). However, a positive reading would be that, as opposed the zero-sum-gain notion, a well-informed incorporation of technology could make the pointy bit a bit bigger (or more pointy). The tech could support us to explore a constantly shifting and, I hope, expanding, notion of humanness. This idea is very much in tension with the Surveillance Capitalism, Silicon Valley, reading of our times. I’m not saying that the tech does support us to explore our humanity, I’m saying it could and what is involved in that ‘could’ is worth thinking about.

Source: David White

5 ways in which AI is discussed

Helen Beetham, whose work over at imperfect offerings I’ve mentioned many times here, has a guest post on the LSE Higher Education blog about AI in education.

She discusses five ways in which it’s often discussed: as a specific technology, as intelligence, as a collaborator, as a model of the world, and as the future of work. In my day-to-day routine, I tend to use it as a collaborator, because I have (what I hope to be) a reasonable mental model of the capacities and limitations of LLMs.

What’s particularly useful about this article is the meta-framing that more ‘productivity’ isn’t always to be valued. Sometimes, what we want, is for people to slow down and deliberate a bit more.

AI narratives arrive in an academic setting where productivity is already overvalued. What other values besides productivity and speed can be put forward in teaching and learning, particularly in assessment? We don’t ask students to produce assignments so that there can be more content in the world, but so we (and they) have evidence that they are developing their own mental world, in the context of disciplinary questions and practices.

Source: LSE Higher Education blog

14 years of Tory (mis)rule

I don’t even have words for how bad the last 14 years have been under the Tories. Thankfully, people who do have the words have written some of them down.

This piece in The New Yorker is very long, but even just reading some of it will help those outside the UK understand what is going on, and those inside it hold your head in shame.

Some people insisted that the past decade and a half of British politics resists satisfying explanation. The only way to think about it is as a psychodrama enacted, for the most part, by a small group of middle-aged men who went to élite private schools, studied at the University of Oxford, and have been climbing and chucking one another off the ladder of British public life—the cursus honorum, as Johnson once called it—ever since.

[…]

These have been years of loss and waste. The U.K. has yet to recover from the financial crisis that began in 2008. According to one estimate, the average worker is now fourteen thousand pounds worse off per year than if earnings had continued to rise at pre-crisis rates—it is the worst period for wage growth since the Napoleonic Wars. “Nobody who’s alive and working in the British economy today has ever seen anything like this,” Torsten Bell, the chief executive of the Resolution Foundation, which published the analysis, told the BBC last year. “This is what failure looks like.”

[…]

“Austerity” is now a contested term. Plenty of Conservatives question whether it really happened. So it is worth being clear: between 2010 and 2019, British public spending fell from about forty-one per cent of G.D.P. to thirty-five per cent. The Office of Budget Responsibility, the equivalent of the American Congressional Budget Office, describes what came to be known as Plan A as “one of the biggest deficit reduction programmes seen in any advanced economy since World War II.” Governments across Europe pursued fiscal consolidation, but the British version was distinct for its emphasis on shrinking the state rather than raising taxes.

Like the choice of the word itself, austerity was politically calculated. Huge areas of public spending—on the N.H.S. and education—were nominally maintained. Pensions and international aid became more generous, to show that British compassion was not dead. But protecting some parts of the state meant sacrificing the rest: the courts, the prisons, police budgets, wildlife departments, rural buses, care for the elderly, youth programs, road maintenance, public health, the diplomatic corps.

In the accident theory of Brexit, leaving the E.U. has turned out to be a puncture rather than a catastrophe: a falloff in trade; a return of forgotten bureaucracy with our near neighbors; an exodus of financial jobs from London; a misalignment in the world. “There is a sort of problem for the British state, including Labour as well as all these Tory governments since 2016, which is that they are having to live a lie,” as Osborne, who voted Remain, said. “It’s a bit like tractor-production figures in the Soviet Union. You have to sort of pretend that this thing is working, and everyone in the system knows it isn’t.”

Source: The New Yorker

Identifying things that don't work

I always find something I agree with in posts like this. Here are some of those things in a list of “things that don’t work”:

- Tearing your hair out because people don’t follow written instructions. You can fill your instructions with BOLD CAPS and rend your garments when this too fails. A more pleasant option is to craft supportive interfaces where people don’t need instructions. I’m convinced the best interface in history is the beginning of Super Mario Brothers. You just start.

[…]

- Doing unto others as you would have them do unto you. This is a beautiful idea, but often other people simply don’t have the same needs you do.

[…]

- Trying to figure it all out ahead of time. For hard problems, you can sit around trying to see around all corners and anticipate all possibilities. This can work—when Apollo 11 landed on the moon, everything worked the first time. But it’s really hard. If you can, it’s easier to build a prototype, learn from the flaws, and then build another one. (This, of course, contradicts the previous point.)

[…]

Things that work: Dogs, vegetables, index funds, jogging, sleep, lists, learning to cook, drinking less alcohol, surrounding yourself with people you trust and admire.

Source: Dynomight

The art of distraction

L.M. Sacasas has written a lengthy commentary on an essay by Ted Gioia, which is well worth reading in its entirety. The main thrust of Gioia’s essay is that we have substituted ‘dopamine culture’ for the arts and creative pursuits. Sacasas believes that this is too simplistic a framing.

I’m quoting the part where he uses Pascal to show Gioia, and anyone else who holds a similar point of view, that human beings have been forever thus. Except these days we live like kings of old, where we have the means to be distracted easily and at will. I think, in general, we’re far too bothered about how other people act, and not bothered enough about how we do.

It might be helpful to back up a few hundred years and consider a different telling of our compulsive relationship to distraction, and from there to ask some better questions of our current situation. Writing in the mid-seventeenth century, the French polymath Blaise Pascal wrote a series of strikingly relevant observations about distraction, or, as the translations typically put it, diversions. Frankly, these centuries-old observations do more, as I see it, to illuminate the nature of the problem we face than an appeal to dopamine and they do so because they do not reduce human behavior to neuro-chemical process, however helpful that knowledge may sometimes be.

Pascal argued, for example, that human beings will naturally seek distractions rather than confront their own thoughts in moments of solitude and quiet because those thoughts will eventually lead them to consider unpleasant matters such as their own mortality, the vanity of their endeavors, and the general frailty of the human condition. Even a king, Pascal notes, pursues distractions despite having all the earthly pleasures and honors one could aspire to in this life. “The king is surrounded by persons whose only thought is to divert the king, and to prevent his thinking of self,” Pascal writes. “For he is unhappy, king though he be, if he think of himself.”

We are all of us kings now surrounded by devices whose only purpose is to prevent us from thinking about ourselves.

Pascal even struck a familiar note by commenting directly on the young who do not see the vanity of the world because their lives “are all noise, diversions, and thoughts for the future.” “But take away their

devicesdiversions,” Pascal observes, “and you will see them bored to extinction. Then they feel their nullity without recognizing it, for nothing could be more wretched than to be intolerably depressed as soon as one is reduced to introspection with no means of diversion.”I don’t know, you tell me? I wouldn’t limit that description to the “young.” What do you feel when confronted with a sudden unexpected moment of silence and inactivity? Do you grow uneasy? Do you find it difficult to abide the stillness and quiet? Do your thoughts worry you? Solitude, as opposed to loneliness, can be understood as a practice or maybe even a skill. Have we been deskilled in the practice of solitude? Have we grown uncomfortable in our own company and has this amplified the preponderance of loneliness in contemporary society? Recall, for instance, how Hannah Arendt once distinguished solitude from loneliness: “I call this existential state [thinking as an internal conversation] in which I keep myself company ‘solitude’ to distinguish it from ‘loneliness,’ where I am also alone but now deserted not only by human company but also by the possible company of myself.”

It seems to me that these are all now familiar issues and tired questions. As observations about our situation, they now strike me as banal. We all know this, right? But perhaps for that reason we do well to recall them to mind from time to time. After all, Pascal would also tell us that the stakes are high, quite high. “The only thing which consoles us for our miseries is diversion, and yet this is the greatest of our miseries,” he writes. “For it is this which principally hinders us from reflecting upon ourselves, and which makes us insensibly ruin ourselves. Without this we should be in a state of weariness, and this weariness would spur us to seek a more solid means of escaping from it. But diversion amuses us, and leads us unconsciously to death.”

Source: The Convivial Society

The problem with private property societies

I still subscribe to a few author’s publications on Substack, although I wish they’d leave the platform. One of these is Antonia Malchik’s On The Commons whose posts often include a turn of phrase which really resonates with me.

This week, I’ve been listening to Ep.24 of Hardcore History: Addendum where the host, Dan Carlin, interviews Rick Rubin, the legendary music producer. Towards the end, Rubin turns the tables and asks Carlin a few questions. One of them is about what life was like before land ownership. Carlin, who usually hugely impresses me, seemed to suggest that humans have always owned land in one way or another, and that it’s only aberrations where it was collectively owned.

I’m not sure that’s true. I think Carlin would do well to read, for example, Dave Graeber’s The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Private ownership of everything is something that seems to be burned into the American psyche. But it doesn’t have to be this way. As Malchik points out in her post, private ownership within a capitalist economy is essentially why we can’t have nice things.

In their book The Prehistory of Private Property, authors Karl Widerquist and Grant S. McCall repeatedly go back to the main difference that they see in a private property society versus one where private ownership of, say, land, much less water and food, is unknown: freedom to leave. That is, if you want to walk away from your people, or your place, can you do so and still support yourself? Can you walk away and find or make food, shelter, and clothing? In non-private property societies, the freedom to walk away and still live just fine is the norm. In private property societies, it’s almost nonexistent. You have to work to make rent. Land-rent, you might call it. Someone else owns the land, and you have to pay to live on it.

The extent to which this reality runs counter to most of our existence, even if we’re just counting the few hundred thousand years that Homo sapiens have been here and not the millions of years of hominin evolution before that, is mind-bending. There have been territories and civilizations and controlling empires for thousands of years all over the world, but for most of our species’ existence, most humans had some kind of freedom to live on, with, and from land without needing to pay someone else for the privilege of existing. Until relatively recently.

We can’t all spend our time as we would wish not just because capitalism allows a few humans to hoard an increasing amount of money and power, but because the planet’s dominant societies force land to be privately owned, and make access to food and clean water something we have to pay for.

Source: On The Commons

More equal societies perform better

It’s easy to say that you hate the Tories. The reason, of course, is that while they’re in government they institute policies and pass laws that make the country more unequal. This is problematic for everyone, not just those impoverished.

This well-referenced article is published in Nature. I’d also check out this video I saw posted to LinkedIn (but originally from TikTok) about the argument about more capitalism not being better.

Even affluent people would enjoy a better quality of life if they lived in a country with a more equal distribution of wealth, similar to a Scandinavian nation. They might see improvements in their mental health and have a reduced chance of becoming victims of violence; their children might do better at school and be less likely to take dangerous drugs.

[…]

Many commentators have drawn attention to the environmental need to limit economic growth and instead prioritize sustainability and well-being. Here we argue that tackling inequality is the foremost task of that transformation. Greater equality will reduce unhealthy and excess consumption, and will increase the solidarity and cohesion that are needed to make societies more adaptable in the face of climate and other emergencies.

[…]

Other studies have also shown that more-equal societies are more cohesive, with higher levels of trust and participation in local groups16. And, compared with less-equal rich countries, another 10–20% of the populations of more-equal countries think that environmental protection should be prioritized over economic growth. More-equal societies also perform better on the Global Peace Index (which ranks states on their levels of peacefulness), and provide more foreign aid. The UN target is for countries to spend 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) on foreign aid; Sweden and Norway each give around 1% of their GNI, whereas the United Kingdom gives 0.5% and the United States only 0.2%.

Source: Nature