Bad historical maps

Like the author of this article, I love a good map. Whether it’s trekking across hills and mountains with an OS map, or looking through historical maps, there’s something enchanting about understanding territories.

The thing is, though, that maps are literally projections. They leave things out and therefore have to be interpreted. If the maps are out of date, or are being used in a way that’s anachronistic, that leads to a huge problem.

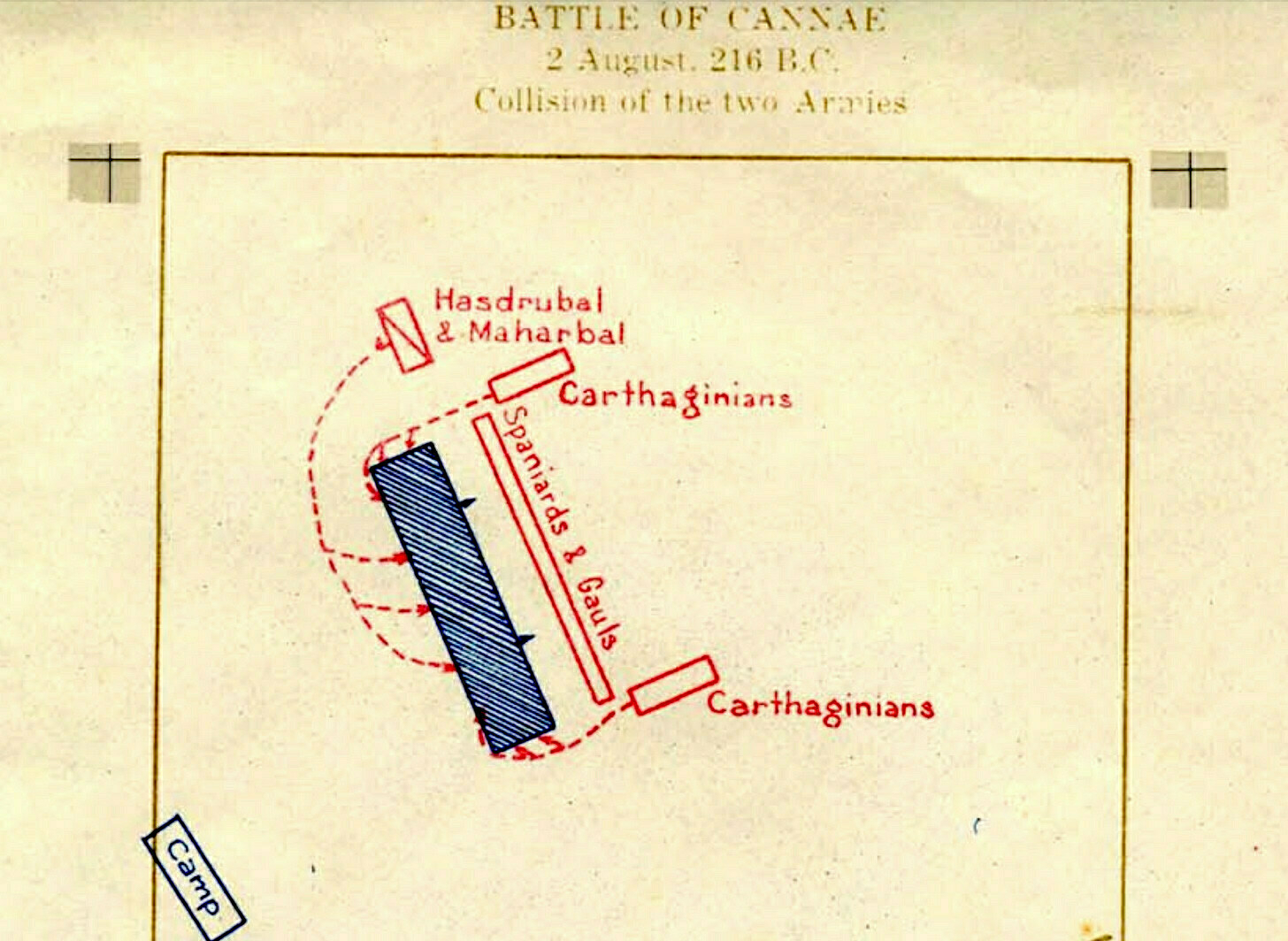

As a History teacher, I used to teach WWI but didn’t know that General von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff, was obsessed with Hannibal and the Battle of Cannae. Apparently he used stories and maps of how it played out to inform his strategy. The problem was that, not only did it happen a couple of millennia beforehand, but it probably didn’t even play out that way.

Maps like this are a big part of why I became a historian. I probably spent more time looking through the volumes of Colin McEvedy’s Penguin Atlas of History series than any other book when I was a kid.... There’s something beguiling about the thought that a simple arrangement of lines might explain the world — like seeing human history as an enormous game of Civilization 6. But of course, that’s also the problem with using maps as a way of understanding history. If you’re not careful, they go from being helpful tools to misleading simplifications.Source: Historical maps probably helped cause World War I | Res Obscura[…]

In her book The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman argues that the memory of Cannae, which was passed down through a succession of military histories until it became a virtual obsession of strategists in the 19th century, helped push the world into an unimaginable catastrophe.

It did so by offering up a model of a “battle of annihilation” that Germany’s war planners believed they could unleash on France. At the head of these planers was General von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff. The map of Cannae haunted Schlieffen’s dreams.

[…]

Cannae was no vague inspiration. It was a direct model for Germany’s invasion of Belgium and France.

[…]

As the historian Martin Samuels pointed out in his article “the Reality of Cannae,” there is no archaeological evidence for the battle. Nor are there first-hand sources of any kind. Everything we know derives from accounts written sixty years or more after Cannae itself. Suffice to say, when Samuels dug into these sources, he found as many questions as answers. The detailed maps of movements at Cannae that decorated military strategy manuals for hundreds of years, in other words, were largely fanciful. Samuels calls Cannae “the most quoted and least understood battle” in history.

The simplicity of a historical map — the clear labels, the sharp edges, and above all the reduction of thousands or millions of people into abstract symbols — is a big part of why they’re so beguiling. But it’s also why they lead us astray.

[…]

It is sometimes said that the map is not the territory. The map is not the historical argument, either.

Instead, maps are a great way to pose questions about history. They are best approached as a way in: an entry-point rather than an ending. They offer one path toward confronting the enormous complexity of “real” history — the kind made by individual people, on the decidedly imperfect and unmap-like terrain of the world.