They’re not rejecting technology. They’re choreographing it.

An inability to focus is a design problem. As I noted back in 2020 on my now-defunct literaci.es blog, perhaps we need notification literacy (archive.org link).

If the problem is screens inherently, then we need cultural revival, a return to books, perhaps even a neo-Luddite retreat from technology. But if the problem is design, then we need design activism and regulatory intervention. The same screens that fragment attention can support it. The same technologies that extract human attention can cultivate it. The question is who designs them, for what purposes, and under what constraints.

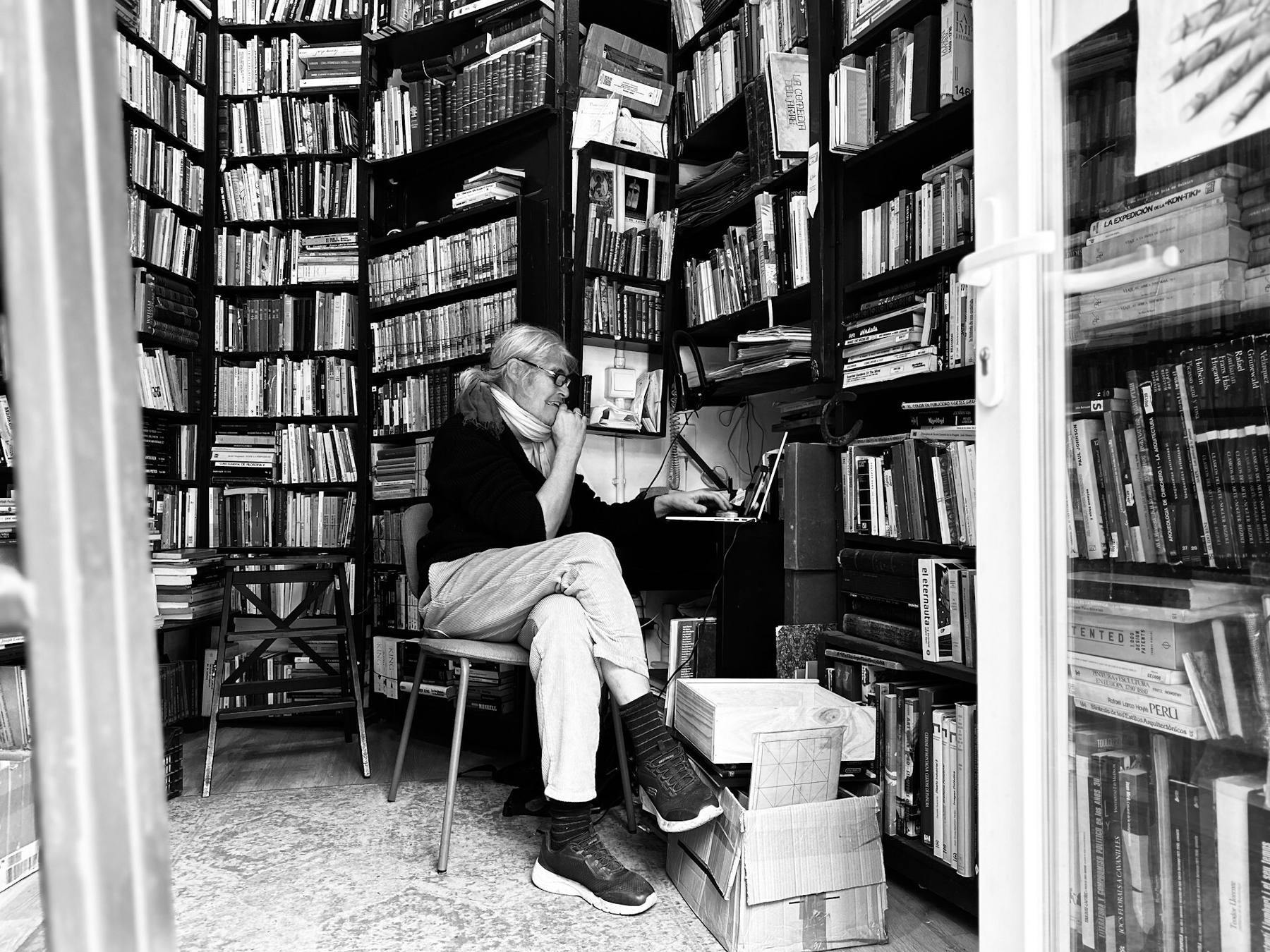

In the library, I watch people navigate information in ways that would have seemed impossible to previous generations. A research question that once required weeks of archival work now takes hours. But more than efficiency has changed. The nature of synthesis itself has transformed.

Ideas now move through multiple channels simultaneously. A documentary provides emotional resonance and visual evidence. Its transcript enables the precision needed to locate a specific argument. A newsletter unpacks the implications. A podcast allows the ideas to marinate during a commute. Each mode contributes something the others cannot. This isn’t decline. It’s expansion.

What strikes me most is the difference between people who’ve learned to construct what I call ‘containers for attention’ – bounded spaces and practices where different modes of engagement become possible – and those who haven’t. The distinction isn’t about intelligence or discipline. It’s about environmental architecture. Some people have learned to watch documentaries with a notebook, listen to podcasts during walks when their minds can wander productively, read physical books in deliberately quiet spaces with phones left behind. They’re not rejecting technology. They’re choreographing it.

Others are drowning, attempting sustained thought in environments engineered to prevent it. They sit with laptops open, seven tabs competing for attention, notifications sliding in from three different apps, phones vibrating every few minutes. They’re trying to read serious material while fighting a losing battle against behavioural psychology weaponised at scale. They believe their inability to focus is a personal failure rather than a design problem. They don’t realise they’re trying to think in a space optimised to prevent thinking.

This is where my understanding of literacy has fundamentally shifted. I used to believe, as I was taught, that literacy was primarily about decoding text. But watching how people actually learn and think has convinced me that literacy is about something deeper: the capacity to construct and navigate environments where understanding becomes possible.

Source: Aeon

Image: Mario Aziz

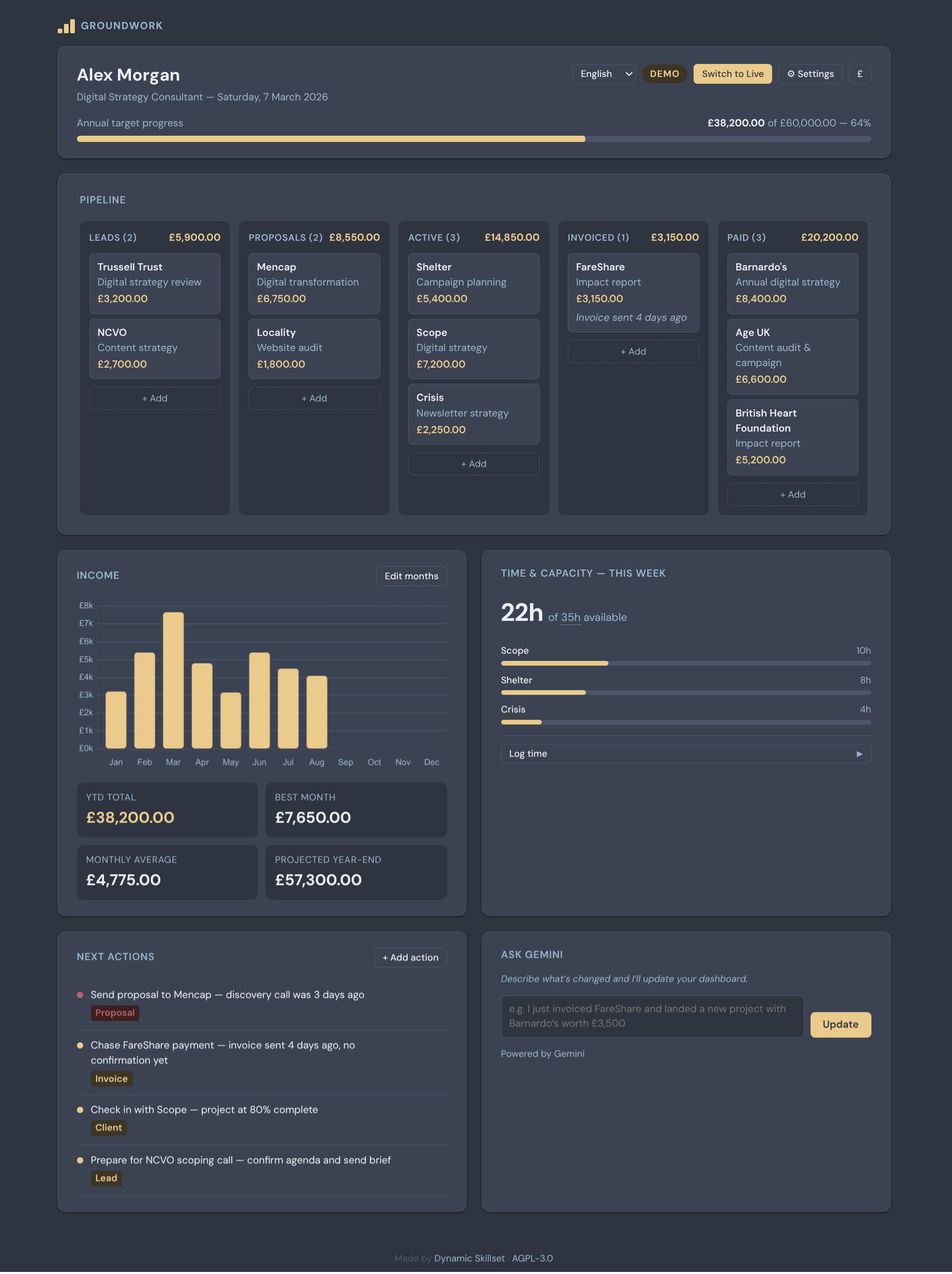

Groundwork

This week I shared my Claude-based ‘bizdev dashboard’ with a few people on some Slack channels of which I’m part. Some people have gone on created equally-useful personalised dashboards, and I’m running a session next Friday to help anyone who wants some guidance.

Meanwhile, I’ve been iterating a single-file offline, private dashboard for tracking projects and profitability for freelancers. I’ve called it ‘Groundwork’ and you simply download index.html and run it in your browser.

A dashboard for freelancers that lives entirely on your computer. Track your leads, income, time, and to-do list — without subscriptions, accounts, or sending your data anywhere.

What it does

- Pipeline — see all your work at a glance, from first conversation to getting paid. Drag jobs across columns as they progress (Lead → Proposal → Active → Invoiced → Paid).

- Income — a monthly bar chart showing what you’ve earned, your best month, and a projected year-end total based on your average.

- Time & capacity — log hours by client, see how your week is filling up, and keep an eye on your workload.

- Next actions — a simple to-do list with priority levels so you know what to tackle first.

- Ask AI — describe a change in plain English and the dashboard updates itself. “Moved the Acme project to invoiced” or “Logged 3 hours on the Barnardo’s website” — that kind of thing. Completely optional.

That last point is pretty cool. Although it can be used entirely manually, there’s also the option to connect it to an LLM via an API key from ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini. You can also use a local LLM via Ollama. Oh, and it’s multi-lingual, has various colour options, and is fully accessible.

Source: GitHub

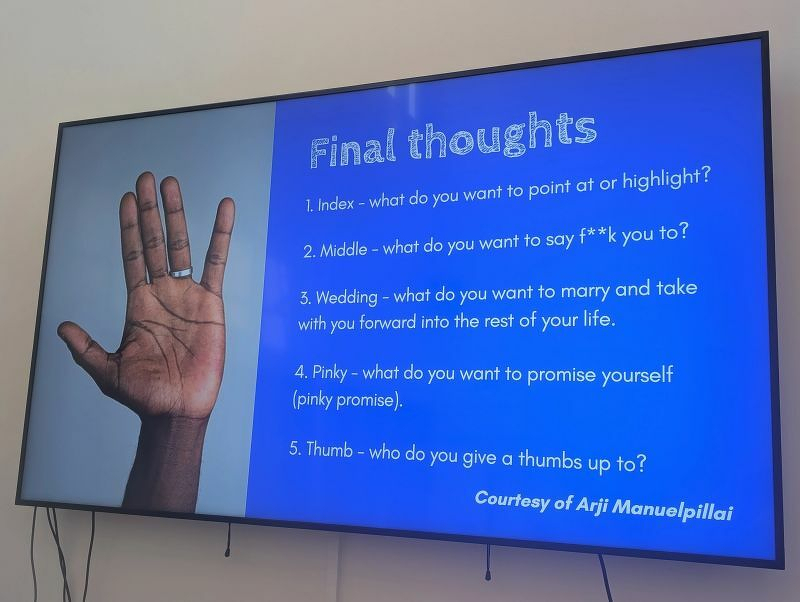

Finger-based checkout

As a facilitator, I do love an innovative end-of-session activity. This one made me smile.

👉 Index: What do you want to point at or highlight?

🖕 Middle finger: What do you want to say f**k you to?

💍 Wedding: What do you want to marry and take with you for the rest of your life?

🤞Little / pinky: What do you want to promise yourself (pinky promise)?

👍 Thumb: What do you give a thumbs up to?

Source: LinkedIn

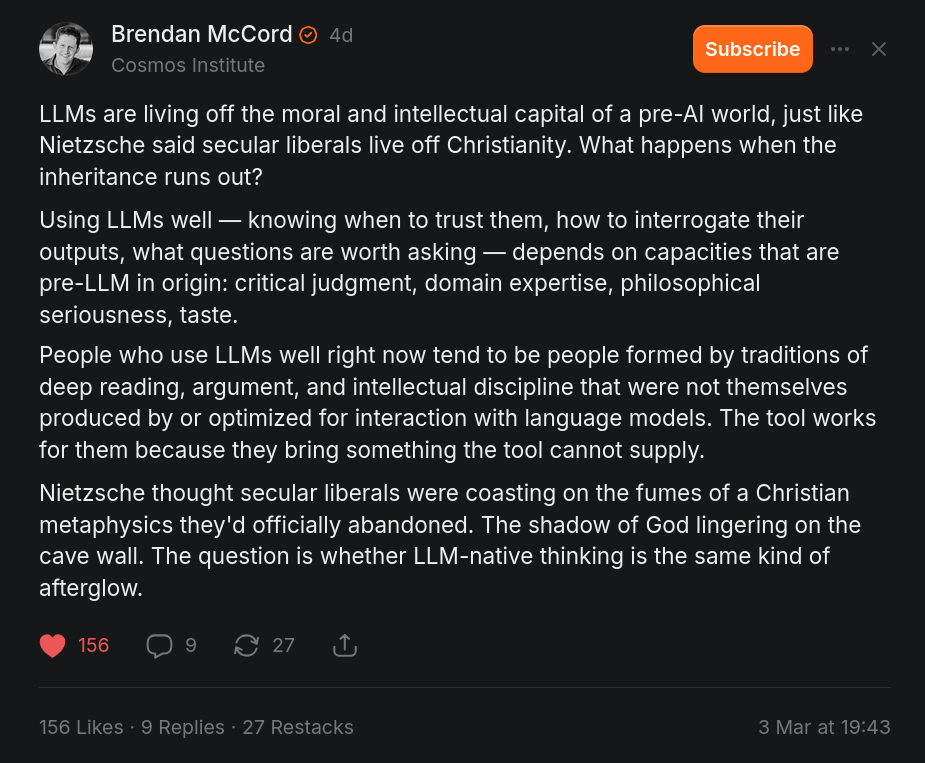

Living off the moral and intellectual capital of a pre-AI world

As one of the comments underneath this notes, “Millennials might be the last generation formed by the new and old, deep enough in intellectual tradition to have taste, early enough in the internet to lead this new era.”

Source: Substack Notes

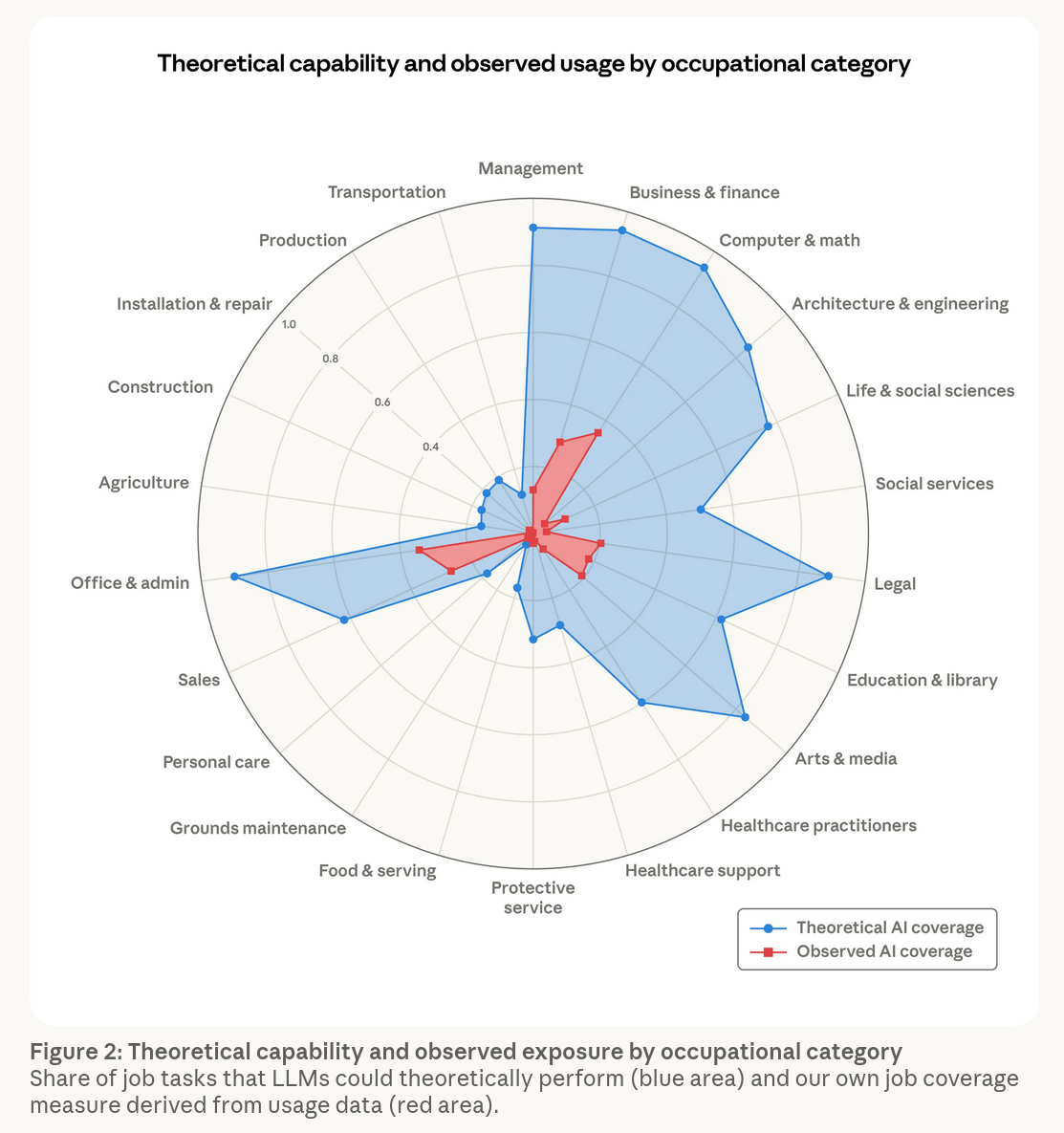

How to avoid your white collar turning blue: brilliance, influence, and relationships

The opening of this piece by Anu Atluru, which I’ve quoted below, is one of the clearest explanations of the shift that’s happening in so-called “white-collar” work at the moment. Their explanation of luxury workers' rights is spot-on.

AUTONOMY. CREATIVE OWNERSHIP. A SEAT AT THE TABLE. The right to say no, not like that, or not right now. Flexible schedules. Remote work. A title that keeps getting better. The expectation that your opinion shapes direction. The expectation that your resources scale with seniority.

These are among what I call luxury workers’ rights. They sit on top of human rights, civil rights, and workers’ rights. They’re the terms of a job meant to make work feel more meaningful and make you feel more valued. We typically associate them with white collar work and view them as moral principles, but they’ve always been a form of compensation for the scarcity of cognitive labor.

White collar work as we’ve known it is cognitive labor with a personhood premium—autonomy over the work itself and value attached to the person doing it. Cheap capital and high margins made it easy for companies who needed human intelligence to pay these premiums. Software’s surplus has been subsidizing our ego-scaffolding. But we’re facing the big shift now.

The early narrative was that AI would kill blue collar jobs first, but it turns out the real world is full of friction, and in the meantime, AI got a lot better at thinking. So it’s white collar work that’s exposed. AI is making intelligence abundant, and when the scarcity of anything drops, the premiums drop with it.

If you strip white collar jobs of their luxury rights, the line between blue and white collar gets a lot thinner. The professional laptop class is staring down its biggest reshaping and identity crisis since industrialization.

After suggesting that a return to the apprenticeship model might be in order for junior professionals, Atluru turns to what that means for the rest of us. How do we avoid being fired and re-hired with blue collar conditions?

MAKE YOURSELF SCARCE AGAIN. If we are indeed headed this direction, and you still want the luxury rights and compensation and glory, the answer is in the mechanism itself. The premium was always tied to scarcity. AI compressed it. So the way back is to go where you’re still scarce—or become something that can’t be compressed again.

What makes you scarce?

BRILLIANCE — You’re so good at something or so rare in your combination of skills (scientific, technical, creative, strategic) that you can’t be scoped into a trade. Your taste, voice, and judgment alone are a strong value proposition.

INFLUENCE — You have a name, an audience, a brand that engages high-value communities. Your taste is signal and cultural influence is power. People want to be associated with you, and that affiliation arbitrage is worth the overhead.

RELATIONSHIPS — You’re the person the founder trusts, the client wants to work with, that just makes the team better, and people just want to be around.

Relatedly, it might be worth exploring the Wikipedia article on elite overproduction which is identified as a cause of social instability.

Source: Working Theorys

Image: Anthropic

Customised pixel graphics from classic games

I learned to touch-type when I was about 11 years old using Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing which came free via the floppy disk of PC Magazine. I was sad to later learn that Mavis was a fictional character.

There are many iconic screens in this games collection which you can customise to your own ends. Fun!

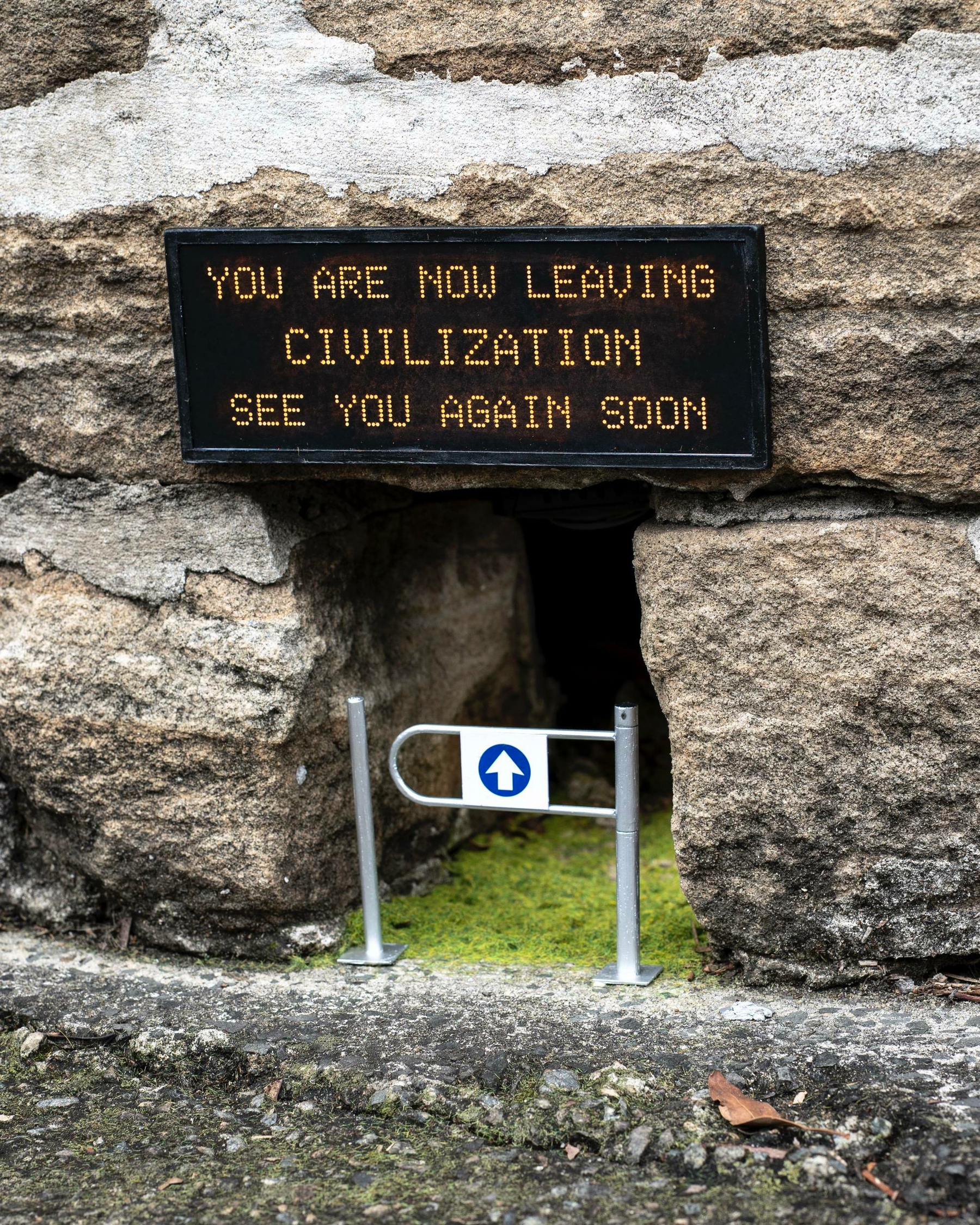

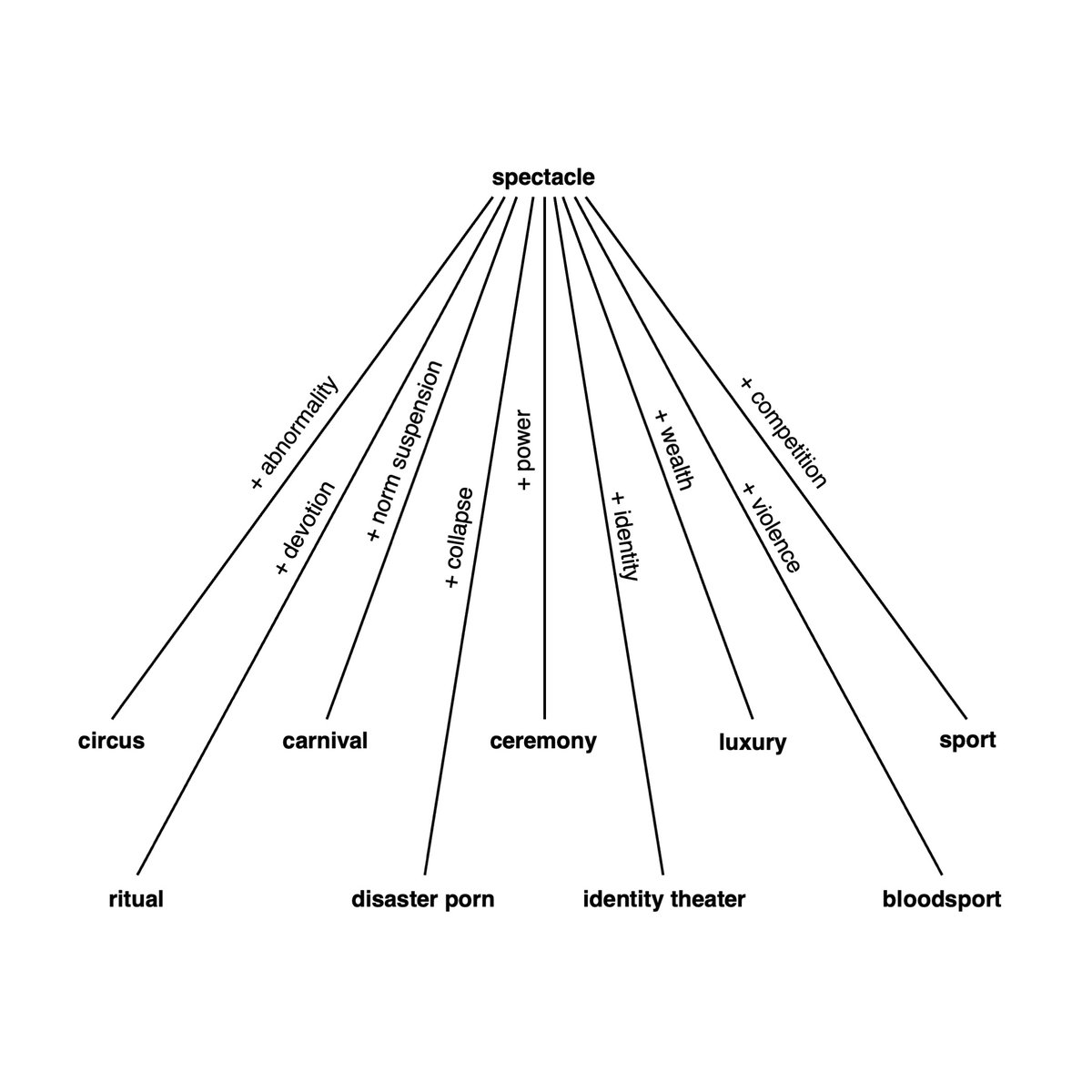

The spectacle produces hypernormalisation

We live in a world of ‘spectacle’ which Guy Debord would have recognised, as both described and predicted it. This is closely linked to the idea of ‘hypernormalisation’ in which surreal events are presented as normal.

Source: Are.na

Building a news canary

I’ve been toying with the idea of a new website, (because obviously what I need to do is own more domains and produce more content…)

Anyway, what do you think of the following? It’s something I’ve been refining since the start of the year, so that every Sunday I (personally) get an email focused on what’s happened, and what happens next.

I’ve been refining a (looooong) prompt to find interesting news stories, press releases, viral posts, etc. that might suggest things are changing culturally, socially, politically, and economically. I’ve asked for the inclusion of something from each continent over the 10 news stories — and, of course, not to be too US-focused.

Is this something you’d subscribe to? 🤔

(again, this wouldn’t be a Thought Shrapnel thing)

1. US–Israeli strikes on Iran and Khamenei’s death

US and Israeli forces have launched large air and missile strikes against targets in Iran, with reports of explosions in Tehran and other cities and widespread fear inside the country. Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has been reported killed, with US President Donald Trump publicly confirming his death and analysts quickly turning to the question of succession and the balance of power among Iranian elites. Iran has responded with missile attacks on Israel and multiple Gulf states, killing at least one person in Abu Dhabi and shaking cities that normally promote an image of safety and stability.

What happens next?

Key watchpoints include the internal succession process in Iran, potential escalation through proxies across the region, and the reaction of energy and shipping markets to the risk of prolonged instability around the Gulf.

Links:

- Reuters — Iranian leader Khamenei killed in air strikes as U.S., Israel launch attacks

- BBC — Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei killed in US strikes

- Al Jazeera — Iran confirms Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei dead after US-Israeli attacks

2. Global reaction and Brazil’s condemnation of the strikes

Brazil’s government has condemned the US–Israeli strikes on Iran, voicing “grave concern” and distancing itself from Washington’s approach to the crisis. Reactions from governments worldwide show a mix of criticism, appeals for restraint, and guarded support, revealing fractures in traditional alliances and a more fragmented diplomatic field. Several states that backed sanctions on Russia are clearly less willing to endorse this round of military action, signalling fatigue with sanctions‑plus‑strikes as a default Western toolkit.

What happens next?

Brazil and other large democracies in the Global South are likely to continue presenting themselves as independent actors and potential mediators, which complicates efforts by Washington and its allies to portray responses to Iran as a simple binary choice.

Links:

- Reuters — Brazilian government condemns strikes on Iran

- Al Jazeera — World reacts to US, Israel attack on Iran, Tehran retaliation

- Critical Threats — Iran Update Evening Special Report: February 28, 2026

3. Bolivia’s crashed cash plane and burned banknotes

A Bolivian Air Force Hercules carrying new central‑bank banknotes crashed on a busy avenue in El Alto, killing around 20 people and injuring dozens, with cash scattered across the crash site. Residents rushed to collect the notes and clashed with security forces, who then burned large quantities of recovered money on site, arguing that it was not yet legal tender and that possession would be illegal. The scenes, captured and shared widely, have touched a nerve in a city already feeling the effects of fuel subsidy cuts and price rises.

What happens next?

The combination of mass casualties and the spectacle of the state incinerating money in front of poor residents is likely to become a powerful reference point in Bolivian politics, feeding anger about inequality, austerity, and institutional trust.

Links:

- Reuters — Residents protest as authorities burn cash left on ground by Bolivian plane crash

- ABC News (Australia) — Bolivian plane carrying banknotes crashes, leaving 20 people dead

- The Guardian — At least 15 killed as cash-laden military cargo plane crashes in Bolivia

4. Vietnam’s AI law takes effect

Vietnam’s Law on Artificial Intelligence comes into force on 1 March 2026, making it the first country in Southeast Asia with a detailed AI statute covering developers, deployers, and users. The law requires clear labelling of AI‑generated content, notification when people interact with AI rather than humans, and stricter controls for high‑risk applications in areas such as health, finance, and security. It is tied to an industrial strategy that includes building national AI computing capacity, strengthening Vietnamese‑language data resources, and encouraging domestic AI firms.

What happens next?

Global platforms and AI companies face a choice between adapting products to meet Vietnam’s standards and potentially drawing on them elsewhere, or limiting services in a market that is positioning itself as a digital hub in the region.

Links:

- France 24 — Vietnam AI law takes effect, first in Southeast Asia

- IAPP — Vietnam’s first standalone AI Law: An overview of key provisions and future implications

- Baker McKenzie — Vietnam: Artificial Intelligence Law – Foundation and Outlook

5. Zimbabwe bans exports of raw minerals and lithium concentrates

Zimbabwe has ordered an immediate halt to exports of all unprocessed minerals and lithium concentrates, including consignments already in transit, citing malpractice and a need to capture more value at home. The ban affects foreign miners and downstream processors who rely on Zimbabwean ore for global battery and electronics supply chains. It aligns with a broader push across several African states to renegotiate their place in extractive industries and to reduce dependence on external financing.

What happens next?

Mining companies must weigh investment in local processing against sourcing from other countries, and other resource‑rich governments may view Zimbabwe’s stance as a precedent, reshaping bargaining power in critical mineral markets.

Links:

- Reuters — Zimbabwe bans exports of all raw minerals and lithium concentrates, cites malpractices

- S&P via Reuters — Africa faces $90 billion debt wall in 2026, S&P says

- Chatham House — Africa in 2026: Global uncertainty demands regional leadership

6. Africa CDC challenges pathogen‑data conditions in US health deals

Africa CDC Director Jean Kaseya has raised “major concerns” over proposed US health‑security agreements that require rapid sharing of pathogen samples and genomic data as a condition for funding. Zimbabwe has already pulled out of talks on a large deal, and Zambia has pushed back over equity and sovereignty issues, arguing that past arrangements have seen data and samples leave the continent without fair access to resulting products. The dispute comes as African governments seek more voice in global health governance after the Covid‑19 experience.

What happens next?

Future pandemic treaties and bilateral agreements are likely to feature much tougher African demands on benefit sharing, local manufacturing, and data governance, which may slow negotiations but could rebalance long‑standing patterns of extraction.

Links:

- Reuters — Africa CDC head cites major concerns over data, pathogen sharing in US deals

- BMJ Global Health — COP27 climate change conference: urgent action needed for Africa and the world

- Africa CDC — Director-General addresses equity and data governance in global health partnerships

7. EU social fund can help pay for access to abortion

The European Commission has clarified that EU member states may use money from the European Social Fund Plus to finance access to safe abortion, including cross‑border care for people from countries with tighter laws. The clarification does not impose new obligations on governments but gives legal and financial cover to those that decide to support such services. It lands in a context where abortion access within the EU is diverging, with some states restricting and others expanding rights.

What happens next?

Expect legal and political disputes about whether EU‑level money is being used to bypass national restrictions, and debates about how far EU social and cohesion tools should reach into sensitive areas of bio‑politics.

Links:

- Reuters — EU says social fund can be used to allow access to safe abortions across bloc

- Cambridge — Governing Europe’s Recovery and Resilience Facility: Between Discipline and Discretion

- Politics and Governance — Governing the EU’s Energy Crisis: The European Commission’s Geopolitical Turn and its Pitfalls

8. Draft EU–India trade deal with MFN clause and digital provisions

A draft text of the EU–India trade agreement shows plans for each side to grant the other Most Favoured Nation treatment for five years after entry into force, limiting scope to offer better terms to other large partners. The draft also includes provisions on digital trade, including data, online services, and rules for tech firms, set against the backdrop of broader EU moves on AI and platform regulation. For India, the deal is part of a diversification effort away from China and towards multiple partners.

What happens next?

If ratified on current lines, the agreement will influence India’s choices on data governance and digital regulation and will set a reference point for trade talks between advanced economies and large emerging markets that seek more autonomy.

Links:

- Reuters — India and EU lock in WTO guardrails, digital trade rules in draft trade deal

- Reuters — Europe sets benchmark for rest of the world with landmark AI laws

- Global Policy Watch — EU Regulators Issue Opinion on Revisions of GDPR and Other Data Laws

9. Canada’s Bill C‑16 and changing online‑harms rules

Analysis from regulatory commentators notes that Canada’s Bill C‑16 broadens obligations from telecoms and ISPs to a wider group of “internet services”, including large platforms and infrastructure providers. The bill introduces new criminal offences around coercive control and updates non‑consensual intimate image provisions to include deepfakes and other AI‑generated content. Civil liberties organisations warn about possible conflicts with Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, while groups working on gender‑based violence argue that stronger tools are overdue.

What happens next?

Once passed, the law is expected to face court challenges and will force platforms to adapt moderation, evidence, and transparency practices, feeding into a larger pattern of diverging national approaches to online harms.

Links:

- The Modern Regulator — February 2026 regulatory update: from passage to practice

- MoFo — Key Digital Regulation & Compliance Developments (February 2026)

- Canadian Civil Liberties Association — Online Harms Legislation and Charter Rights

10. Fiji and Tuvalu to host pre‑COP31 climate meetings

The Pacific Islands Forum has announced that Fiji and Tuvalu will host key meetings in the run‑up to COP31, which will take place in Australia in 2026. Fiji will host the pre‑COP gathering and Tuvalu will host a dedicated leaders’ segment, giving some of the most climate‑vulnerable states greater influence over agenda setting. Forum leaders present this as a chance to centre Pacific priorities such as loss and damage, adaptation finance, and fossil‑fuel phase‑out.

What happens next?

With pre‑COP and COP activity concentrated in and around the Pacific, larger emitters face stronger diplomatic pressure from small island states on issues such as fossil‑fuel production, climate‑related migration, and debt relief linked to resilience.

Links:

- Reuters — Fiji and Tuvalu to host pre-COP31 climate meetings

- AP News — What is the Pacific Islands Forum? How a summit for the world’s tiniest nations became a global draw

- Climate Action Tracker — Australia

Image: César Ardilla

Enough is enough

Today, the pedo-authoritarian US and genocidal Israel attacked Iran to distract from respective domestic problems. At the time of writing, reports are that 85 people have died after strikes hit a girls school.

So, to put that in perspective, innocent girls have died in attempt to cover up a president’s obvious involvement in a sex trafficking ring, and another leader’s issues caused by starving a neighbouring country to death.

Source: Bluesky

Super Mario World Map

I don’t know the original source of this, but I think it’s quite old. A reverse image search led to 118 pages of results…

Source: Klaus Zimmerman

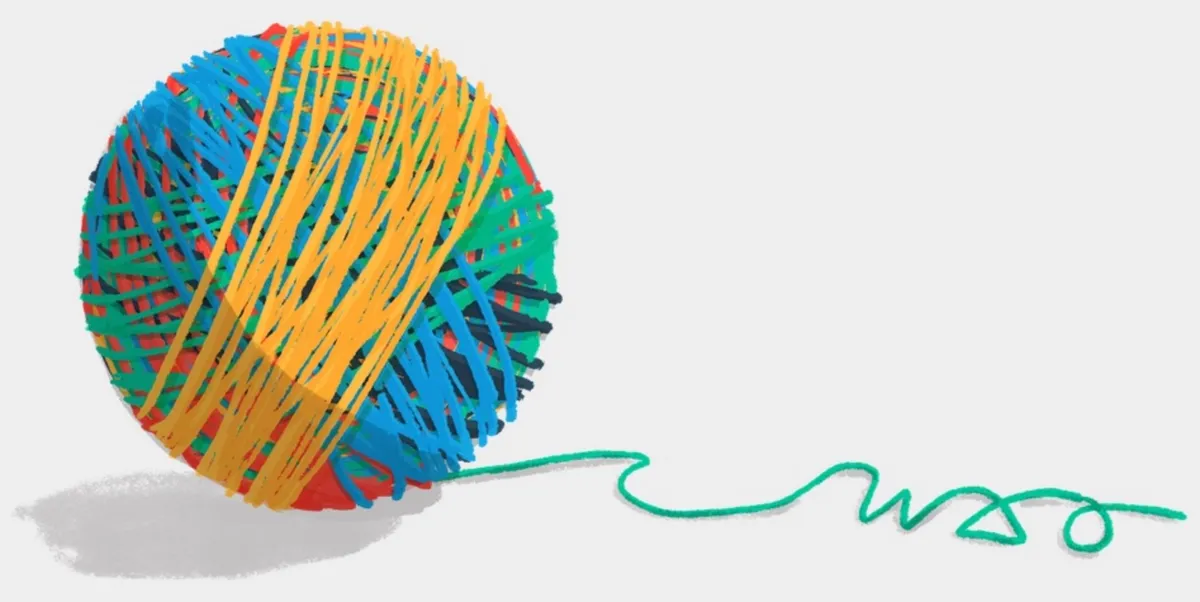

WAO is closing

I know some people only read Thought Shrapnel and not the rest of my work, so I’m just going to give a quick update to say that the co-op I helped set up 10 years ago, and which has been a source of creative and collaborative inspiration, will be closing on 1st May 2026.

We’re all still friends. I’m going to be working through my consultancy business, Dynamic Skillset so get in touch if I can help you or your organisation!

After ten years of creative cooperation, we’re announcing that We Are Open Co-op (WAO) will close its doors on our 10th birthday: 1st May 2026. This has been a carefully considered, collaborative decision — the kind we’ve always tried to model as a co-op.

But, as you can imagine, we’re a bit emotional about it, and it also feels a bit weird to finally say it out loud and in public.

WAO is a strong, well-respected brand. We continue to have wonderful clients, meaningful work and good relationships with each other. People are finally waking up to the idea that flat hierarchies and consent-driven businesses are the future.

In some ways, this is a continuation rather than an ending, as we’ll be carrying forward the cooperative principles we’ve practised into new systems and relationships.

Source: WAO blog

Image: CC BY-ND Visual Thinkery for WAO

Agentic commerce is a catastrophe for every business whose moat is made of friction

I’m too young for memories of the original game on the Commodore 64, but I do remember the SEGA Master System version of Spy vs. Spy. While I wasn’t allowed to have a console myself, I would play on friends' devices. The thing I really remember, though, is my parents leaving me to play for a while which was on a demo unit in Fenwick’s toy department in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. It was a game in which you, as either the ‘black’ or ‘white’ spy had to outwit the other spy.

This homely introduction serves to explain the graphic accompanying both this post and the one I’ve take it from — an extremely clear-eyed view of what “agentic commerce” means for brands. Usually, this kind of thing wouldn’t interest me, but I do like clear thinking on things orthogonal to my line of work.

Let’s start with the setup, which involves a post on an influential blog which was more “speculative fiction” than “investor advice”:

For context: Citrini Research is a financial analysis firm focused on thematic investing research with a highly influential Substack. The piece in question, published this past Sunday, is a fictional macro memo written from June 2028, narrating the fallout of what they call the “human intelligence displacement spiral” – a negative feedback loop in which AI capabilities improve rapidly, leading to mass white collar layoffs, spending decreases, margins tightening, companies buying more AI, accelerating the loop. It’s all a “scenario, not a prediction,” and not really all that new: the idea that a (unit of AI capex spend) < (unit of disposable income) circulating in the real economy has been doing the rounds for a while now. Yet Citrini caused a very real market selloff earlier this week. Apparently this scenario wasn’t priced in.

What the smart people at NEMESIS point out is that our current neoliberal version of capitalism in advanced service-based economies has “built a rent-extraction layer on top of human limitations” as “[m]ost people accept a bad price to avoid more clicks or cognitive labor [with] brand familiarity substituting for diligence.”

In Citrini’s scenario, AI agents dismantle this layer entirely. They price-match across platforms, re-shop insurance renewals, assemble travel itineraries, route around interchange fees etc. Agents don’t mind doing the things we find tedious.

Basically what Citrini is describing as the destruction of habitual intermediation is, from the POV of Nemesis HQ, a description of one of the primary economic functions of brands dissolving.

Essentially, brands “reduce the friction of decision-making” because it’s a shortcut to buying more of what you know you like. There’s a reason I’ve got three Patagonia hoodies, four Gant jumpers, and all of my t-shirts are from THG. But what happens when an agent which knows your preferences can go off and do your shopping for you? Book your holiday? Organise your insurance renewals?

In Citrini’s 2028 world of agentic commerce, brand loyalty is nothing but a tax. When given license to do so, the agent doesn’t care about your favorite app or branded commodity, feel the pull of a well-designed checkout UX flow or default to the app your thumb navigates to the easiest on your home screen. It evaluates every option on price, fit, speed, or whatever other parameters you’ve set. The entire edifice of brand preference built over decades of advertising, design and behavioral psychology becomes, from the agent’s perspective, noise.

Though its not a wholesale “end of brands” it is a catastrophe for every business whose moat is made of friction. And a remarkable number of moats are made pretty much of only friction (think: insurance, financial services, telecom, energy, SaaS, most platforms, Big Grocery, airlines, cars, etc.). Generally speaking, this is a good thing (creative destruction!), and frees the labor of large swaths of branding and marketing professionals to societally more useful ends.

What I think scares people is uncertainty. I probably have a higher tolerance for different forms of ambiguity than most people I know. Well, cognitively, at least; sometimes the body keeps the score.

Source & image: NEMESIS

Units of attention

Good stuff from Jay Springett, who also links to a 60-page PDF called Paying Attention that I… haven’t paid attention to (yet!)

The attention economy rewards the same behaviours regardless of whether the content being spread is a coordinated disinformation campaign or a genuinely interesting essay. The platform does not distinguish between the two. It just measures the engagement.

There is a practical implication buried somewhere in the above though I think.

That if the first units of attention are the ones that change behaviour most, then being liberal with the like button actually matters. dLeaving a comment, sharing a post, replying to something you found worthwhile are small acts that actually work. In the face of “the firehose” the modest counter-move is to be deliberate about where your attention goes, and cultivating the things that you want to see more of.

This is interesting when juxtaposed with something Nita Farahany says in the transcript of a conversation posted on The Exponential View:

This gets at a fundamental question about what it means to act autonomously. Are you acting in a way consistent with your own desires, or are you being steered by somebody else’s desires? There’s very little we do these days that is steered by our own desires.

I’m teaching a class this semester at Duke on mental privacy, advanced topics in AI law and policy. I ran an attention audit on my students. They recorded how many times they picked up their devices over three days, and what they spent their attention on. Day one: record it, don’t change your behaviour. Day two: no apps that algorithmically steer you — which meant basically nothing was allowed. Day three: do whatever you want, record it again. Day two was remarkable. Somebody read a book. They couldn’t remember the last time they’d done that. These are students. Someone finished a puzzle they’d been convinced they didn’t have time for. And day three? Worse than day one. Utterly sucked back in.

I was flicking back through my notebook, which I have not used enough in the last 18 months or so, and came across a note I’d made while reading Oliver Burkeman’s excellent book Four Thousand Weeks. He quotes Harry Frankfurt as saying that our devices distract us from more important matters — it’s as if we let what they show us define what counts as “important”. As such, our capacity to “want what we want to want” is sabotaged.

Sources:

Image: Marcus Spiske

👋 A reminder that I’ve been on holiday this week, so no Thought Shrapnel.

However, I’ve still been saving things to my Are.na channels if you’d like to peruse those…

– Doug

TechFreedom

As explained in this post, Tom Watson and I are putting together an offer to help organisations with their digital sovereignty.

Sign up if you’re interested in joining our first cohort. No obligation.

You cannot manage what you cannot see. Most organisations operate in a fog of invisible reliance; you rely on platforms that obscure their workings behind slick interfaces and terms you never read.

TechFreedom helps you clear the air. We give you the tools to look past Big Tech’s version of the Cloud and build a digital infrastructure that is open, visible, and under your control.

Source: techfreedom.eu