Things have changed

I know Martin Waller from the early days of Twitter when we were both teachers. The ‘Multi’ part of his ‘MultiMartin’ handle is due to his work on multiliteracies, the subject of his postgraduate study. He’s written plenty of papers and spoken at more than a few events.

Martin dropped off my radar a bit, but on reconnecting with him this week, he pointed me towards this post. I think we’re going to see a lot more of this over the next few years. How would Gwyneth Paltrow put it, “conscious decoupling” from online life, maybe?

I’ve… taken the decision to completely remove myself from social media including most online messaging services. I was once an advocate of the use of social media and digital technologies and have published book chapters and spoken at events around the world about it in education. I have made so many wonderful connections and friends over the years on the internet and through social media. However, things have changed. The landscape and current climate can be toxic and dangerous. I’ve stumbled upon comments on Facebook and Instagram which have made me feel sick. I’ve read different messenger channels where comments have ridiculed people for no good reason. There’s also just too much information out there and it isn’t helpful to be exposed to it all, all of the time. It makes it difficult to switch off, think and focus on what matters.

Source: MultiMartin

Image: Chris Barbalis

A bit of composting

There’s a lot of people thinking about endings at the moment. Not just because we’re getting into the post-Covid era now, but also due to things like the huge swathes of layoffs in the US, and the general economic downturn in the UK and other countries.

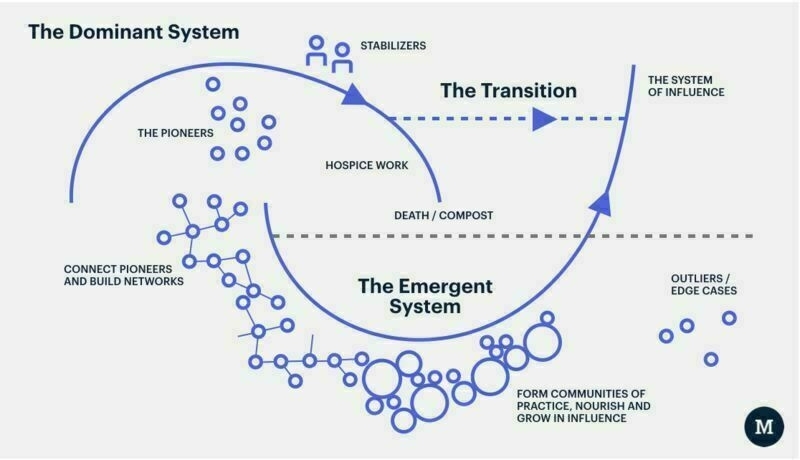

Things start and things end. That’s what they do. Change is constant, which is something difficult to get used to. In this post, Tom Watson talks about ‘composting’ which is a key part of the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops model, which he doesn’t actually reference but is extremely relevant.

I’d also say working openly helps with having good endings. The chances are that what has been learned during the project can take root elsewhere, and therefore live on, if people can see into the project. We should treat projects less as raised beds for pretty flowers and more like mycelium networks.

I thought about the social enterprise I had with my dad. I’ve got lots of things wrong in life, but doing that definitely wasn’t one of them. I learned a lot, about caring, kindness, not following the bullshit, and community. It ended, like all organisations do. But I was proud that we were able to financially support a group to continue meeting and chatting, and supporting each other. It wasn’t much, but it was something. And just last year we donated the last of our funds, around £6k, to a charity rewilding in Scotland, where the C for Campbell in my name comes from via my dad.

This felt like a good ending. A bit of composting. But not every organisation can pass on finances at the end, in fact it’s pretty rare, because often the root cause of the ending is money. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have things of value to pass on. They have resources, knowledge and wisdom. And I couldn’t help thinking about all that is lost, again and again when things end.

[…]

[W]e need to think broader about endings and composting. Not just when an organisation ends, but when programmes and projects end. What about all the research reports, the data from projects, the experiments that worked and those that didn’t. What about all that knowledge, what about all that potential wisdom. It’s why we spend time up front cataloguing all the things we do in a project along the way. It’s not perfect, but it’s something.

Source: Tomcw.xyz

Image: Innovation Unit

Discussing misinformation for the purpose of pointing out that it is misinformation

ContraPoints is “an American left-wing YouTuber, political commentator, and cultural critic” with the moniker coming from the fact that her content “often provide[s] counterargument to right-wing extremists and classical liberals.” She “utilizes philosophy and personal anecdotes to not only explain left-wing ideas, but to also criticize common conservative, classical liberal, alt-right, and fascist talking points,” with the videos having “a combative but humorous tone, containing dark and surreal humor, sarcasm, and sexual themes.”

I haven’t watched this yet, partly because I struggle to fit watching videos longer than 10 minutes into my day, and partly because it is absolutely the kind of thing I would watch by myself. The first few minutes are fantastic, I can tell you that much, with the focus being on conspiracy theories and misinformation.

Our current level of discourse, where random jokes are treated like they’re chiseled into stone by a divine hand

I’m not Very Online™ online enough to be able to understand what’s going on in popular culture, especially when it comes to the business models, politics, and norms behind it. So, thank goodness for Ryan Broderick, who parses all of this for all of us.

In this part of one of his most recent missives, Broderick talks about Barack Obama joining Bluesky, and the history (and trajectory) of people acting like brands, and brands acting like people. He says a lot in these two paragraphs, which in his newsletter he then goes to connect to the recent incident where a reporter from The Atlantic was accidentally added to a White House Signal war-planning group.

We live in interesting times, but mainly flattened times, where nothing is expected to have any more significance than anything else, and is presented to us via little black rectangle. At this point, I feel like I want to write another thesis on misinformation and disinformation in the media landscape. But perhaps it would be too depressing.

Bluesky made a big splash at South By Southwest earlier this month, with CEO Jay Graber delivering the keynote in a sweatshirt making fun of Mark Zuckerberg. When they made the shirt available for sale, it sold out instantly — in large part because it’s the first time ever that regular people have been able to give Bluesky money. The platform started as a decentralized, not-for-profit research effort, specifically trying to avoid the mistakes of Twitter, and before the shirt, it was still funded entirely by investors. Though, as of last year, they’re working on paid subscriptions. The Bluesky team has been swearing up and down that they’re working to avoid the mistakes Twitter/X has made, but if they eventually offer a subscription to Obama that treats his account identically to yours or mine, they’ve already made the most fundamental mistake here. Because the social media landscape Obama helped create, by blending the casual and the official, is the exact same one Bluesky was founded to work against. If a brand is a person, then a person has to be a brand, especially in an algorithmically-controlled attention economy that’s increasingly shifting literally everything about social media towards getting your money. And more importantly, if a government official or group has a social media presence, it has to be both a person and a brand.

And eight years after Obama walked this tightrope all the way to the White House, Donald Trump ran it up the gut. Trump, unfortunately, understands the delirious unreality of the person/brand hybrid better than maybe anyone else on the planet. Well, he might be tied with WWE’s Vince McMahon. But Trump’s first administration established a precedent of treating his tweets as official statements. And more directly than anything I’m blaming Obama for here, Trump sent us on the rollercoaster that just loop-de-looped past “a shitty website is all the transparency the US government needs” a few weeks ago. Now, there’s no difference between a post that’s an executive order, a commercial, or someone saying whatever bullshit is on their mind. In fact, it must serve as all of the above. On one end of this, you get our current level of discourse, where random jokes are treated like they’re chiseled into stone by a divine hand.

Source: Garbage Day

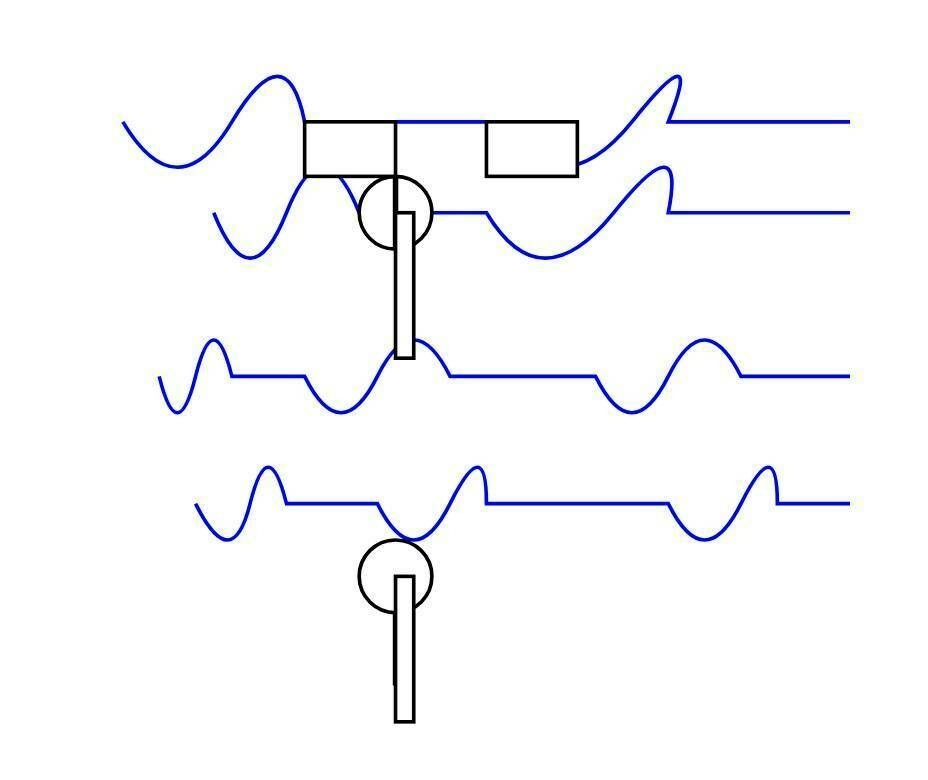

Image: Mastodon (various accounts posted this, couldn’t find the original)

Essentially a checklist of weird Instagram shit

I’m officially middle-aged, so have given up trying to understand under-40s culture. However, it’s still worth studying, especially when it’s essentially algorithmically-determined.

In this article, Ryan Broderick gives the example of Ashton Hall, a fitness influencer:

Hall’s video, which was originally shared to his Instagram page back in February, is essentially a checklist of weird Instagram shit. A dizzying mix of products and behaviors that make no sense and that no normal person would ever actually use or try, either because Hall figured out that they’re good for engagement on his page or because he saw them in other videos because they were good for those creators’ engagement.

And so we have things that people do, and are watched doing, because an inscrutable algorithm has decided that this is what people want to watch. So this is what is served, what people consume, and therefore the content which influencers make more of. And so it goes.

Culture shifts, and not always in good ways. As the Netflix series Adolescence shows, there is a sinister underbelly to all of this. But then that is, in itself weaponised to suggest that some way to fix or solve things is to ban digital devices. Instead of, you know, digital and media literacies.

In terms of physical safety, one of the most dangerous things you can do is laugh at someone who considers themselves hyper-masculine. But this is also the correct response to all of this stuff. It’s ridiculous. So the key is to point out how ridiculous it is to boys and young men, not in a way that condemns other (unless it’s someone like Andrew Tate) but rather just how it doesn’t make any sense.

“Fifteen years ago this routine would get you called gay (or ‘metrosexual’) but is now considered peak alpha male behavior. Something weird has shifted,” influencer and commentator Matt Bernstein wrote of Hall’s video. And, yes, something has shifted. Which is that these people know that there are a lot of very sad men that are going to get served their videos, and they’re fully leaning into it.

Guys like Hall are everywhere, with vast libraries of masculinity porn meant to soothe your sad man brain. Nonsexual (usually) gender-based content, like the trad wives of TikTok, targets your desires the same way normal porn does. Unrealistic and temporarily fulfilling facsimiles of facsimiles that come in different flavors depending on what you’re into. There’s a guy who soaks his feet in coke. A guy who claims he goes to a gun range at six in the morning. A guy who brings a physical book into his home sauna. A guy who’s really into those infrared sleep masks and appears to have some kind of slave woman who has to bow to him every morning before he takes it off. A guy who does the face dunk with San Pellegrino, rather than Saratoga. An infinitely expanding universe of musclemen who want to convince you that everything in your life can be fixed if you start waking up at 4 AM to journal, buy those puffy running shoes, live in a barely furnished Miami penthouse, have no real connections in your life — especially with women — and, of course, as Hall tells his followers often on Instagram, buy their course or ebook or seminar or whatever to learn the real secrets to success.

And I’ve been surprised that this hasn’t come up more amid our current national conversation about men. Because this is the heart of it. There are a lot of very large, very dumb men who want you to sleep three hours a night and invest in vending machines and do turmeric cleanses and they all know that every man in the country is one personal crisis away from being being algorithmically inundated by their videos. And as long as that’s the case, there’s really nothing we can do to fix things.

Source: Garbage Day

Image: Screenshot of video from Ashton Hall, fitness influencer

This confirms all my prejudices, I am pleased to say

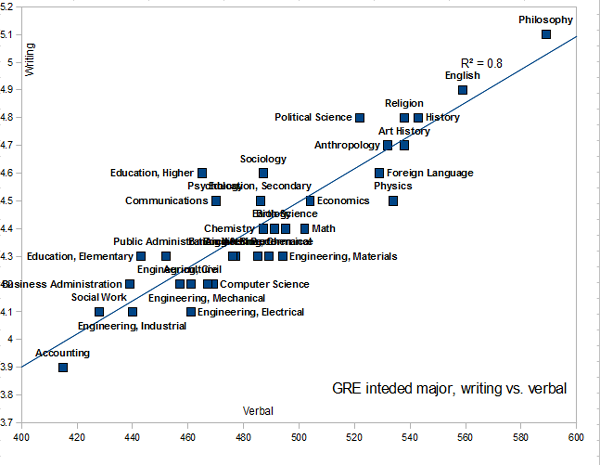

I had a much-overdue catch-up with Will Bentinck earlier today, during which I discovered he holds a first-class degree in Philosophy! Obviously, Philosophy graduates are legimtimately The Best™ so my already high opinion of him scaled new heights.

Talking of scaling new heights, check out what happens when you plot Philosophy graduates' verbal against writing scores. All of which backs up my opinion that a Humanities degree is, in general, the best preparation for life. And, more specifically, it helps you with levels of abstraction that are going to be even more relevant and necessary in our AI-augmented future…

This data suggests (but falls a long way short of establishing) that if we want to produce graduates with general, across-the-board smarts, physics and philosophy are disciplines to encourage [and possibly also that accountancy and business administration should be discouraged (this confirms all my prejudices, I am pleased to say!)].

Source: Stephen Law

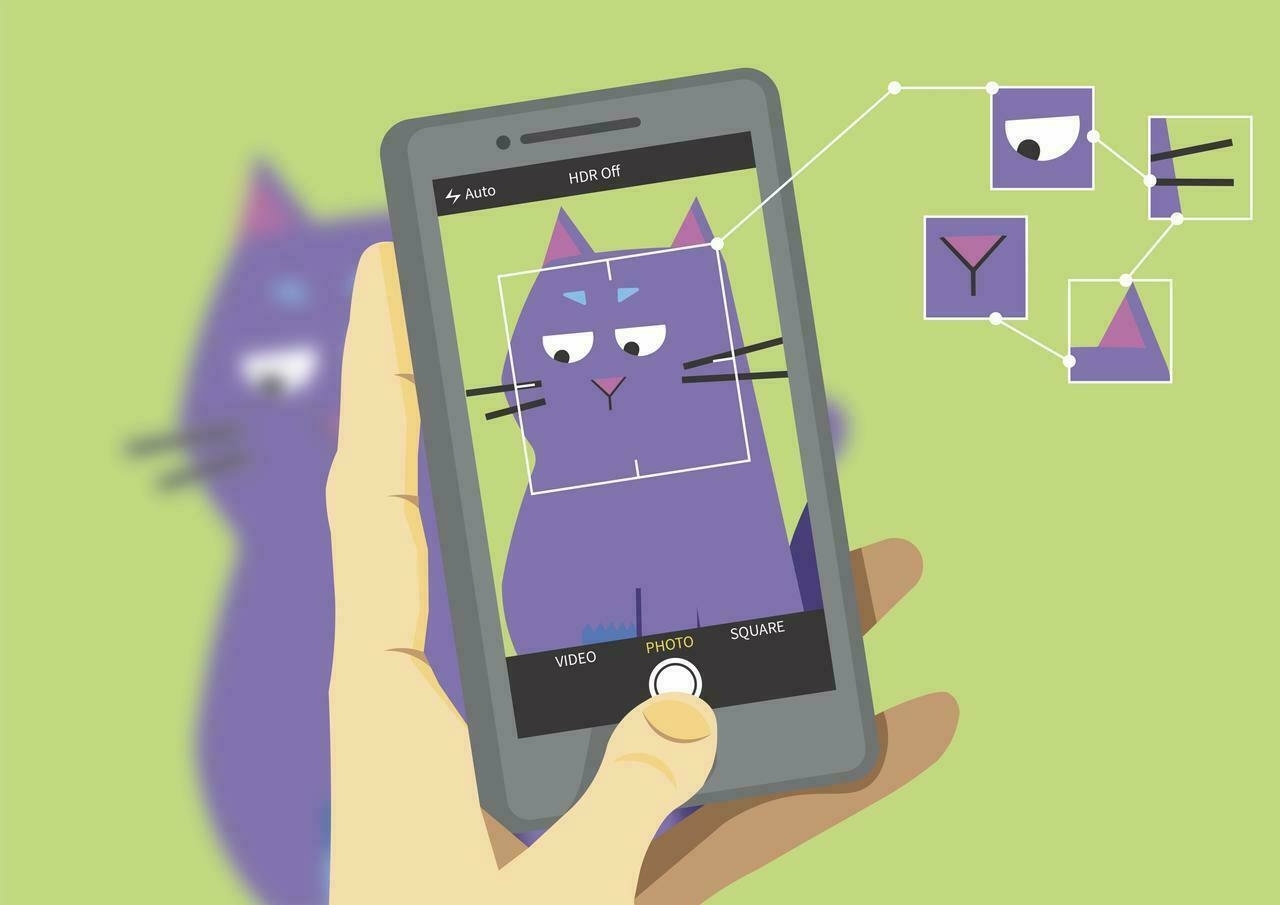

Just seek to understand, and remember we understand a lot by doing

After some success ‘vibe coding’ both Album Shelf and a digital credentials issuing platform called Badge to the Future, I’ve run a couple of sessions called ‘F*ck Around and Find Out’ relating to AI. I also knocked up a career discovery tool.

I’m sharing all of these links because I think people should be experimenting with generative AI to see what it can do and where the ‘edges’ are. I said as much when recording a episode for Helen Beetham’s imperfect offerings podcast which I’m hoping will come out soon.

Discussing some of this on the All Tech is Human Slack, Noelia Amoedo shared this post from her blog. After experimenting with other tools, she like me has settled on Lovable. I used the $50/month tier last month as I ran out of prompts on the $20/month level. You do get some for free.

What I think is explicit in Noelia’s post is the potential decentralisation of power this enables. What is implicit is that it takes curiosity to do this. As I signed off Helen’s podcast as saying (spoiler alert!) “my experience has been that most people are intellectually lazy, extremely uncurious, and want to take something off the shelf, implement it without too much thought, and be considered ‘innovative’ for doing so.”

You might say that being “intellectually lazy” is using AI. But I disagree. So long as you’re not just getting it to answer an essay question or come up with a some trite, fascist-adjacent imagery, then interacting with it involves choice (which model? what prompt?) and creativity.

I settled on Lovable, a Swedish company. The fact that they were European may have influenced my decision… or did I realize that later? I did subscribe, but only for a month (I seem to have learned to moderate my impulses just a bit). I took advantage of a business trip to write the code for my website, and I worked on it between meetings over two days. It must have taken about four or five hours overall, but it could have been done in one or two hours if the content had been ready when I started. It is possibly longer than what it would have taken with WordPress, I admit, but it gave me so much flexibility! I also own the code and I can take it anywhere. I did have to figure out some “techy” things, like how to turn the JavaScript7 code into something that I could upload to my hosting service, but Lovable was right there to provide any instructions I needed, and I have to confess I enjoyed bossing him (it!!!) around to change things here or there.

Asking for something in your own words and getting it done instantly almost feels like magic, just as graphical user interfaces felt magical when we were used to command lines. And if graphical user interfaces opened the digital world to so many people who were not digital till then, conversational user interfaces are already doing the same so much faster.

[…]

I can’t help but wonder: Could this be a way to decentralize and give digital power back to the people? Could small digital companies have a better shot at long-term survival in the new ecosystem that rises, or will power end up even more concentrated? Will this bring tighter software thanks to expert computer scientists empowered by AI, or will the digital space degrade due to a bunch of “spaghetti code” that is difficult to understand and maintain? Will no-code builders like Replit or Lovable bring people closer to understanding code, or will they have the opposite effect?

I have no answers, but let me just say that my curiosity brought me closer to the code than I had ever been in 25 years, and I’d encourage you to do the same: get just a bit closer from wherever your starting point may be. Just seek to understand, and remember we understand a lot by doing. The world is changing very quickly, and the new AI wave will most likely affect you whether you want it or not. You may as well understand what’s coming, and as we would say in Spain, take the bull by the horns.

Source: Noel-IA’s Substack

Image: Snapcat by Oleksandra Mukhachova & The Bigger Picture

The first fully-open LLM to outperform GPT3.5-Turbo and GPT-4o mini

Thanks to Patrick Tanguay who commented on one of my LinkedIn updates, pointing me towards this post by Simon Willison.

Patrick was commenting in response to my post about ‘openness’ in relation to (generative) AI. Simon has tried out an LLM which claims to have the full stack freely available for inspection and reuse.

He tests these kinds of things by, among other things, getting it to draw a picture of a pelian riding a bicycle. The image accompanying this post is what OLMo 2 created (“refreshingly abstract”!) To be fair, Google’s Gemma 3 model didn’t do a great job either.

It’s made me think about what an appropriate test suite would be for me (i.e. subjectively) and what would be appropriate (objectively). There’s Humanity’s Last Exam but that’s based on exam-style knowledge which isn’t always super-practical.

mlx-community/OLMo-2-0325-32B-Instruct-4bit (via) OLMo 2 32B claims to be “the first fully-open model (all data, code, weights, and details are freely available) to outperform GPT3.5-Turbo and GPT-4o mini”.

Source: Simon Willison’s Weblog

Everyone is at least a little bit weird, and most people are very weird

I like all of what I’ve read of Adam Mastroianni’s work, but I love this. I’d enthusiastically encourage you to go and read all of it.

Mastroianni discusses a time when he went for a job interview as a professor, realising that he had a couple of choices. He could be himself, or wear a mask. Ultimately, he decided to be himself, didn’t get the job, but everything was fine.

From there, he talks about the some of the benefits and drawbacks of conformance as a species, noting that taking the mask off is incredibly liberating. I know this from experience, as it was the exact advice given to me by my therapist in 2019/20 and, guess what? Afterwards some people thought I was an asshole. But then, so did people before. At least I know where I’m at now.

[H]istorically, doing your own thing and incurring the disapproval of others has been dangerous and stupid. Bucking the trend should make you feel crazy, because it often is crazy. Humans survived the ice age, the Black Plague, two world wars, and the Tide Pod Challenge. 99% of all species that ever lived are now extinct, but we’re still standing. Clearly we’re doing something right, and so it behooves you to look around and do exactly what everybody else is doing, even when it feels wrong. That’s how we’ve made it this far, and you’re unlikely to do better by deriving all your decisions from first principles.

Maybe there are some lucky folks out there who are living Lowest Common Denominators, whose desires just magically line up with everything that is popular and socially acceptable, who would be happy living a life that could be approved by committee. But almost everyone is at least a little bit weird, and most people are very weird. If you’ve got even an ounce of strange inside you, at some point the right decision for you is not going to be the sensible one. You’re going to have to do something inadvisable, something alienating and illegible, something that makes your friends snicker and your mom complain. There will be a decision tucked behind glass that’s marked “ARE YOU SURE YOU WANT TO DO THIS?”, and you’ll have to shatter it with your elbow and reach through.

[…]

When you make that crazy choice, things get easier in exactly one way: you don’t have to lie anymore. You can stop doing an impression of a more palatable person who was born without any inconvenient desires. Whatever you fear will happen when you drop the act, some of it won’t ultimately happen, but some will. And it’ll hurt. But for me, anyway, it didn’t hurt in the stupid, meaningless way that I was used to. It hurt in a different way, like “ow!…that’s all you got?” It felt crazy until I did it, and then it felt crazy to have waited so long.

Source: Experimental History

Image: JOSHUA COLEMAN

Taking natural-looking motion to yet another level

The above Boston Dynamics video is currently doing the rounds, with yet more human-like movement. It’s pretty impressive.

The usual response to this kind of thing is amusement tinged with fear. But, as with everything, it’s the systems within which these things exist that are either problematic or unproblematic. For example, we have zero problem with these being part of a research facility; we might have reservations if they were used in military situations. But then, we use drones in combat these days?

All of which to say: there are many dangerous and scary things in the world, and there are many dangerous and scary people in the world. The way we deal with these in a sustainable and low-drama way is through policies and process. So, unless I have reason to believe otherwise, I’m going to imagine the robots in these videos doing the jobs that currently require humans doing things that might endanger their health, such as rescuing people from burning buildings, inspecting nuclear reactors, and even doing very repetitive tasks under time pressure in warehouses.

Yes, AI and robots are going to replace jobs. No, it’s not the end of the world.

[L]est we forget who’s been at the forefront of humanoid research for more than a decade, Boston Dynamics has just released new footage of its stunning Atlas robot taking natural-looking motion to yet another level.

[…]

As humans learn to walk, run and move in the world, we start anticipating little elements of balance, planning ahead on the fly in a dynamic and changing situation. That’s what we’re watching the AIs learn to master here.

The current explosion in humanoid robotics is still at a very early stage. But watching Atlas and its contemporaries do with the physical world what GPT and other language models are doing with the world of information – this is sci-fi come to life. […]

These things will be confined to factories for the most part as they begin entering the workforce en masse, but it’s looking clearer than ever that humans and androids will be interacting regularly in daily life sooner than most of us ever imagined.

Source: New Atlas

In many ways, Silicon Valley looks less like capitalism and more like a nonprofit

Yes, yes, more AI commentary but this is a really good post that you should read in its entirety. I’m zeroing on one part of it because I like the analogy of Silicon Valley looking less like capitalism and more like the nonprofit space.

TL;DR: just as we haven’t got fully self-driving cars yet, or any of the other techno-utopian/dystopian technology that was promised years ago, so we’re not about to all be immediately replaced by AI.

Yes, it’s going to have an impact. And, of course, lazy uncurious people are going to use it in lazy uncurious ways. But, the way I see it, we should be more interested in the structures behind the AI bubble. Because although there is useful tech in there, it remains a bubble.

In many ways, Silicon Valley looks less like capitalism and more like a nonprofit. The way you get rich isn’t to sell products to consumers, because you’re likely giving away your product for free, and your customers wouldn’t pay for it if you tried to charge them. If you’re a startup, and not FAANG, the way you pay your bills is to convince someone who’s already rich to give you money. Maybe that’s a venture capital investment, but if you want to get really rich yourself, it’s selling your business to one of the big guys.

You’re not selling a product to a consumer, but selling a story to someone who believes in it, and values it enough to put money towards it. That story of how you can change the world could be true, of course. Plenty of nonprofits have a real and worthwhile impact. But it’s not the same as getting a customer to buy a product at retail. Instead, you’re selling a vision and then a story of how you’ll achieve it. This is the case if you go to a VC, it’s the case if you get a larger firm to buy you, and it’s the case if you’re talking ordinary investors into buying your stock. (Tesla’s stock price is plummeting because Musk’s brand has made Tesla’s brand toxic. But Tesla’s corporate board can’t get rid of him, because investors bought Tesla’s stock—and pumped it to clearly overvalued levels—precisely because they believe in the myth of Musk as a world-historical innovator who will, any day now, unleash the innovations that’ll bring unlimited profits.) (Silicon Valley has, however, given us seemingly unlimited prophets.)

What this means for AI is that, even if the tech bros recognized how far their models are from writing great fiction or solving the trolley problem, they couldn’t admit as much, because it would deflate the narrative they need to sell.

Source: Aaron Ross Powell

Image: Maxim Hopman

Dozens of small internet forums have blocked British users or shut down as new online safety laws come into effect

You won’t see me linking to the Torygraph often, but in this case I want to show that it’s not just left-leaning very online people who are concerned about the UK’s Online Safety Act (2023) which came into force this week.

Neil Brown, a lawyer whose specialities include intenet, telecoms, and tech law, has set up a site collating information provided by Ofcom, the communications regulator. As far as I understand it, Ofcom couldn’t have done a worse job in conjuring up fear, uncertainty, and doubt. There are online forums and other spaces shutting down just in case, as the fines are huge.

This is an interesting time for WAO to be starting work with Amnesty International UK on a community platform for activists. Yet more unhelpful ambiguity to traverse. Yay.

Dozens of small internet forums have blocked British users or shut down as new online safety laws come into effect, with one comparing the new regime to a British version of China’s “great firewall”.

Several smaller community-led sites have stopped operating or restricted services, blaming new illegal harms duties enforced by Ofcom from Monday.

[…]

Britain’s Online Safety Act, a sprawling set of new internet laws, include measures to prevent children from seeing abusive content, age verification for adult websites, criminalising cyber-flashing and deepfakes, and cracking down on harmful misinformation.

Under the illegal harms duties that came into force on Monday, sites must complete risk assessments detailing how they deal with illegal material and implement safety measures to deal with the risk.

The Act allows Ofcom to fine websites £18m or 10pc of their turnover.

The regulator has pledged to prioritise larger sites, which are more at risk of spreading harmful content to a large number of users.

“We’re not setting out to penalise small, low-risk services trying to comply in good faith, and will only take action where it is proportionate and appropriate,” a spokesman said.

Source: The Telegraph

Image: Icons8 Team

In these times of chaos there seems to be a proliferation of new ways of thinking about the nature of reality springing up

There are some people who I follow who have done such interesting stuff in their lives, and whose new work continues to help me think in new ways. Buster Benson is one of these, and his latest post (unfortunately on Substack) is the beginnings of a choose-your-own-adventure style quiz about cosmology, a.k.a. “the nature of reality.”

So… I’ve been thinking a lot about cosmologies, and how in these times of chaos there seems to be a proliferation of new ways of thinking about the nature of reality springing up. If you have a few moments, can you take this short quiz and let me know which result you got, and how you feel about it?

Below you’ll find a some questions designed to help you identify and share your fundamental beliefs about the nature of reality (aka your cosmology). It’s not meant to be a comprehensive survey of all possible cosmologies, but rather a tool to help you identify your own cosmology and perhaps to spark a fun conversation with others. It’s also not meant to critique or judge any of the cosmologies for being more or less true, more or less useful, or more or less good — but rather meant to be window of observation into what beliefs exist out there amongst you all right now.

FWIW, I came out as the following, which (as I commented on Buster’s post) is entirely unsurprising to me:

Pragmatic Instrumentalism — You see scientific theories as powerful tools for prediction and control rather than literal descriptions of an ultimate reality. The value of materialism lies in its extraordinary practical utility and predictive success, not in metaphysical claims about what “really” exists. This pragmatic approach sidesteps unresolvable metaphysical debates while maintaining the full practical power of scientific methodology.

Source: Buster’s Rickshaw

Image: Good Free Photos

Love the casual vibe here

There’s a guy I no longer interact with because I found him too angry. But when I used to follow him, he used to talk about how Big Tech’s plan was to ‘farm’ us. It’s a very Matrix-esque metaphor, but given recent developments and collaborations between Big Tech and the government in the US, perhaps not incorrect?

Businesses like predictability. There’s nothing particularly wrong with that, per se — but, at scale, that can become a bit weird. Think, for example, how odd it is to be reduced to a single button shaped like a ‘heart’ on some social networks to be able to ‘react’ to what someone else has posted. There was a time when people would actually comment more, but the like button has reduced that.

Now, of course, some social networks allow you to ‘react’ in different ways: ‘applause’, perhaps, or maybe you might want to mark that something is ‘insightful’. We might consider doing so as being “better than nothing,” but is it? How does it rearrange our interactions with one another, allowing a particular technology platform (with its own set of affordances and norms, etc.) to intermediate our interactions?

Fast-forward to this month and, of course, Meta is experimenting with a feature that allows people to use AI to reply to posts. This is already a thing on LinkedIn. It’s going about as well as you’d expect.

AI is all over social media. We have AI influencers, AI content, and AI accounts — and, now, it looks like we might get AI comments on Instagram posts, too. What are any of us doing this for anymore?

App researcher Jonah Manzano shared a post on Threads and a video on TikTok showing how some Instagram users now notice a pencil with a star icon in their comments field, allowing them to post AI-generated comments under posts and videos.

[…]

In the video on TikTok that Manzano shared, three comment options are: “Cute living room setup!” “love the casual vibe here,” and “gray cap is so cool.” Unfortunately, all three of these are clearly computer-generated slop and take an already shaky human interaction down a notch.

It’s hard to know why you’d want to remove the human element from every aspect of social media, but Instagram seems to be going to try it anyway.

Source: Mashable

Image: Mimi Di Cianni

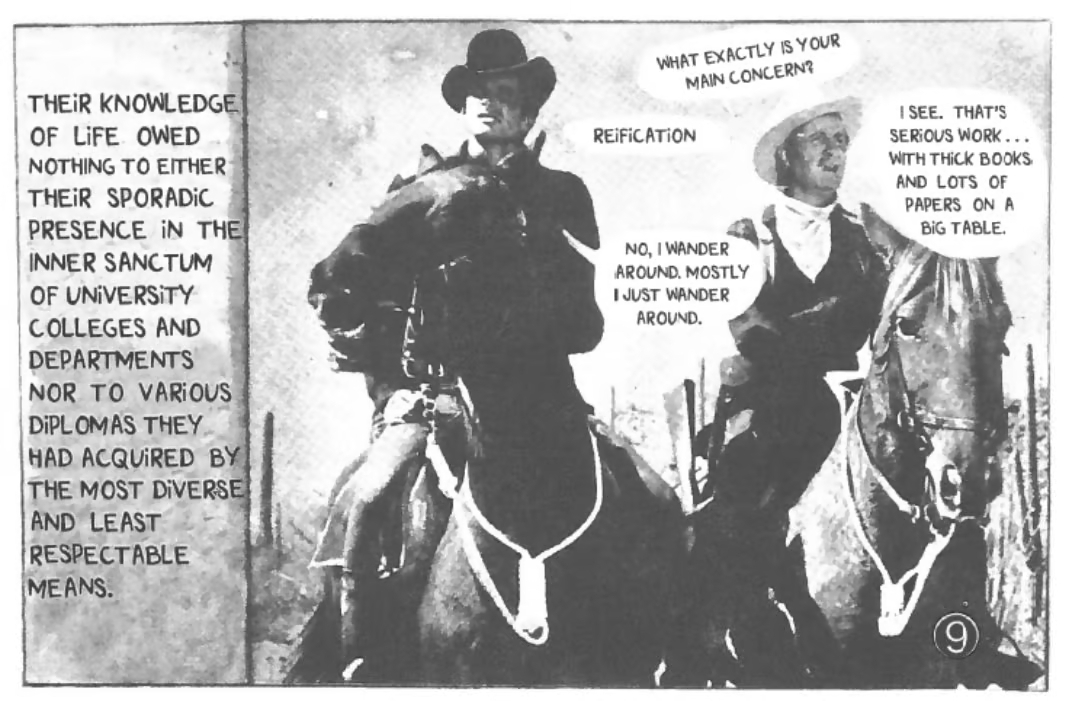

Their knowledge of life owed nothing to their sporadic presence in the inner sanctum of university colleges and departments

Warren Ellis' Orbital Operations is always worth reading, but the most recent issue in particular is a goldmine. I could post every image from it, including the Bayeux Tapestry one. But my mother reads this, and although I’m middle-aged, I still don’t want to disappoint her by including unnecessary profanity here 😅

What interests me about the above image is that this kind of re-contextualisation has been going on for so long, and massively pre-dates the internet. As someone who was a mid-teenager when first getting onto the internet, I’m too young to remember anything like this.

I need to think more about this, but, inspired by Episode #62 of the In Bed With The Right podcast, there’s a way in which you can see AI-generated imagery shared on social media by ‘conservatives’ as the fascist-adjacent version of this. Except, instead of being clever commentary, it’s lazy nostalgia-baiting.

1966: University of Strasbourg Student Union funds are lifted by Situationist sympathisers to print Andre Bertrand’s short comic RETURN OF THE DURUTTI COLUMN, which used stills from Hollywood movies in a process then termed detournement: familiar materials recontextualised in opposition (or at strange angles) to their original intent. This is something so common on the internet now that most people may not know there’s a word for it. The only useful Google hit I can find for Andre Bertrand today is, funnily enough, the Wikipedia page for an attorney who specialises in copyright law.

Source and image: Orbital Operations

Explorers launching into the Fediverse

You may or may not be aware that I use a service called Micro.blog to run Thought Shrapnel these days. It’s the work of a small team, who do a great job. But I bump up against the edges of it quite a lot, especially when it comes to the newsletter/digest.

So I’ve thought for a while about switching to Ghost. Not only is it Open Source, but for the last year they’ve been figuring out ActivityPub integration. That’s the protocol that underpins Fediverse apps such as Mastodon, Pixelfed, and Bonfire. Long story short, there’s a lot to think about in terms of user experience and performance, so getting it right takes a while.

They’ve just announced that those using their Ghost(Pro) hosting can try out the ActivityPub integration for the first time. I’m very tempted to switch, but the cost ($40/month for the number of subscribers we have around these parts) is putting me off. Perhaps if I encouraged more people to become supporters…?

Today we’re opening a public beta for our social web integration in Ghost. For the first time, any site on Ghost(Pro) can now try out ActivityPub.

[T]hanks for your patience! It hasn’t been easy to get this far, but we’re excited to hear what you think as you become one of our very first explorers to launch into the Fediverse.

Source: Ghost Newsletter

Image: Markus Spiske

Don't just put up with how websites are presented to you by default!

I’m sharing this not for the functionality of site, although I’m sure it provides a useful service. Instead, I’m sharing it to demonstrate a point: on the web, you can consume content however you choose. Don’t just put up with how it’s presented to you by default! I could go on about how this a key part of developing digital literacies, but I won’t 😉

In the above gif, I’m using the built in ‘Boosts’ feature of the Arc web browser to change the extremely poor choice of a tiny 8-bit font for something… more readable. This built-in functionality is something you can achieve on other web browsers using tools such as Tampermonkey and Stylish.

Source: Job.Hunt.Works

Affordable building materials out of agricultural waste bonded with oyster-mushroom mycelium

Kenya, much like the UK, has a housing crisis. Mtamu Kililo has an unusual plan to address it: mushrooms. Having just finished Overstory, I am extremely receptive to the kind of nature-first solution that Kililo is proposing goes more mainstream.

One thing I’ve learned during my career to date is that most people are aspirational, meaning that proving that something works for rich or forward-thinking people makes it more palatable to others. For example, if the mushroom bricks discussed here feature on Grand Designs then they’re likely to get some traction.

I wish the world were different and that we could learn from societies that have lived in harmony with nature for millennia. But here we are. I hope that MycoTile is successful and creates a whole new sector of sustainable building materials using waste products. Fingers crossed!

I’m the co-founder and chief executive of MycoTile, which works to produce affordable building materials out of agricultural waste bonded with oyster-mushroom mycelium, a network of tiny filaments that forms a root-like structure for the mushroom.

[…]

MycoTile’s insulation panels have been installed in a few projects, including in student accommodation, and we have seen that the material works. It greatly reduced the sound travelling from one room to the next, and helped to regulate the temperature inside. This insulation is affordable, costing about two-thirds of the price of conventional insulation. And unlike those materials, it can be composted at the end of the building’s life.

[…] The insulation tiles are a success; now we’re working on developing a sturdy block like a brick. When we can produce a brick to build external walls and partitions, it will be a huge step towards affordable housing.

Source: Nature (archive version)

Image: Rachel Horton-Kitchlew

Work is part of our lives, a big part to be sure, but what if it wasn’t our whole life?

I’m composing this on the train on my way back home from a CoTech gathering in London. Post-pandemic, I spend 99% of my working life at home, especially now that there so few in-person events. So I was really glad to spend time among like-minded people and talk about ways we can work together a bit more.

The people I spent time with today are part of a work community. Some of them I count as friends, but none live very close to me. I am, therefore, quite detached from my geographic community, with my only really connection to the place where I live coming through shopping, my kids' sporting activities, and my (temporarily paused) gym membership.

This post by Mike Monteiro responds to a reader question about whether they can be happy even if they hate their job. Monteiro, who identifies as Gen X, harks back to his youth, talking about how school and work was compartmentalised so that people could be themselves outside of those strictures.

The problem now is that, for reasons Monteiro goes into, work invades our homes and community life, hollowing and emptying it out until it’s devoid of meaning. As a result, we have, perhaps unrealistic expectations of what work can provide for us. Except, of course, if you own your own business and work with your friends. I just wish they were nearer by and I got to hang out with them more.

Perhaps I need more offline hobbies.

When we think of our community, we’re likely to picture the people at work. Because it’s where we’re spending the majority of our time. This is by design, but it isn’t our design. It’s the company’s design. In that earlier era, when we still drank from garden hoses, losing a job sucked, but it mostly didn’t take your community with it. In this new era, losing a job means getting gutted. Not only do you lose your paycheck, but you lose access to all the people and places where you used to have your non-work-but-actually-at-work fun. And while your old co-workers will promise that you can still hang out outside work (they mean it, by the way), they’ll soon realize that they don’t really do much “outside work.”

The pandemic put a little bit of a dent in this plan, of course, because you were now working from home, but they adjusted quickly to this by keeping you on wall-to-wall Zoom calls for 12 hours a day. Which wasn’t completely sustainable (even though they said it would be) because when your zoom calls are happening on a laptop facing the window, you eventually start peeking out at what’s beyond that window, and you get curious…

Work is part of our lives, a big part to be sure, but what if it wasn’t our whole life?

They want you to return to work, to their simulation of happiness and community, because they’re afraid that if you don’t you might remember that there was a time when you were free. And you were happy. And you drank from garden hoses.

Source: Mike Monteiro

Image: NOAA

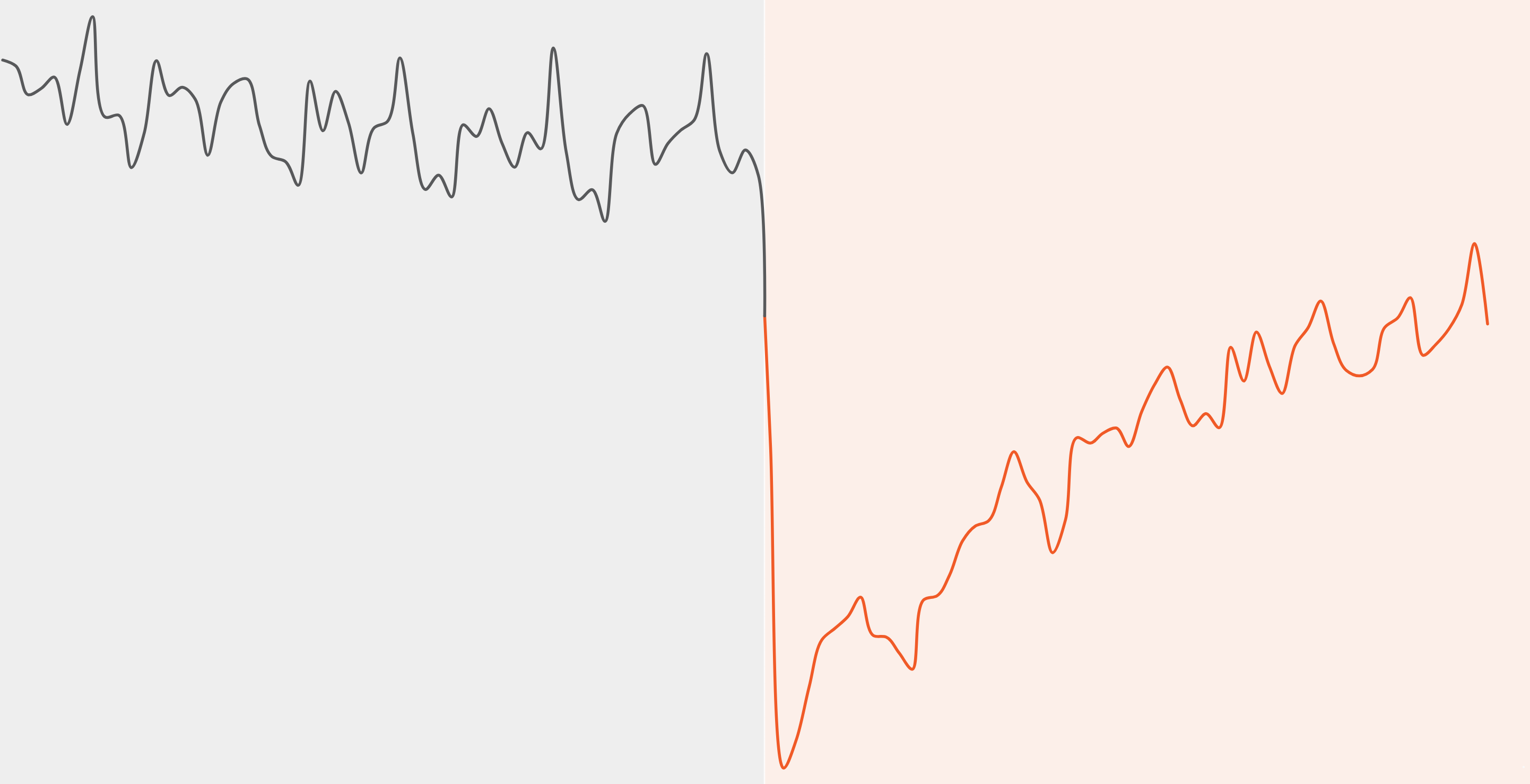

An incomplete collection of charts

Some pretty stark charts showing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the world, in this case using data about the USA. What I like about the way they’ve done this is that, for many of them, ‘trend lines’ are included which allow you to see whether things have gone back to ‘normal’ or stayed… weird.

Over here, unlike other developed nations, the UK has experienced a sharp rise in the post-pandemic number of health-related benefit claims. The number of 16 to 64 year-olds on disability benefits in England and Wales now stands at 2.9m, an increase of almost a million. Around half of those are mental-health related claims. It is ridiculous, therefore that the Labour government is planning to cut disability benefits while “help[ing] those who can work into work.” Forcing, more like.

My wife and I “celebrated” our 40th birthdays during lockdown, so the pandemic has pretty much cleaved our lives into two: there was what came before and now what has come after. At the moment, I massively preferred what came before. How about you?

Decades from now, the pandemic will be visible in the historical data of nearly anything measurable today: an unmistakable spike, dip or jolt that officially began for Americans five years ago this week.

Here’s an incomplete collection of charts that capture that break — across the economy, health care, education, work, family life and more.

Source & image: The New York Times