Time appears in this 3D sort of calendar pattern

It was 18 years ago that I discovered that I’m a bit weird. Like 10-20% of the population, I have a form of synaesthesia, which is usually understood as a “mixing of the senses.” I do get that a bit, but I’m a less extreme of the example of the “spatial-sequence” synaesthesia discussed in this article.

I should imagine the specific details are unique to each synesthete – which is why I debate what “colour” different days of the week and school subjects are with my daughter. However, I recognise being able to see time in three dimensions. Just as with aphantasia we are very surprised when people have a vastly different life to our own.

It was only in my 60s that I discovered there was a name for this phenomenon – not just the way time appears in this 3D sort of calendar pattern, but the colours seen when I think of certain words. Two decades previously, I’d mentioned to a friend that Tuesdays were yellow and she’d looked at me in the same strange, befuddled way that family members always had when told about the calendar in my head. Out of embarrassment, it was never discussed further. I was clearly very odd.

[…]

While thinking about the moment in time I’m at now, I see the day of the week and the hours of that day drawn up in a grid pattern. I am physically in that diagram in my head – and there’s a photographic element to it. If there’s a concert coming up in the calendar, in my mind, a picture of the concert venue is superimposed on to the 7pm to 10pm time slot on that particular day.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Annie Spratt

Somewhere I'd like to spend some time

I saw this and not only did it feel like somewhere I’d like to spend some time, but also reminded me of the cover of Bad Bunny’s Debí Tirar Más Fotos, which was one of my favourite albums of 2025.

Source: Are.na

Postal Arbitrage

I sent a parcel from Brexit Britain to my friend and colleague Laura Hilliger in Germany. The “2-3 day” DHL service cost as much as the contents and took from 18th December to 14th January to arrive. I could have just ordered something from Amazon.de for her with free postage and it would have arrived next day.

This article takes things a step further: why send letters and postcards to friends and family when you can order actual products from Amazon to be delivered along with a gift note?

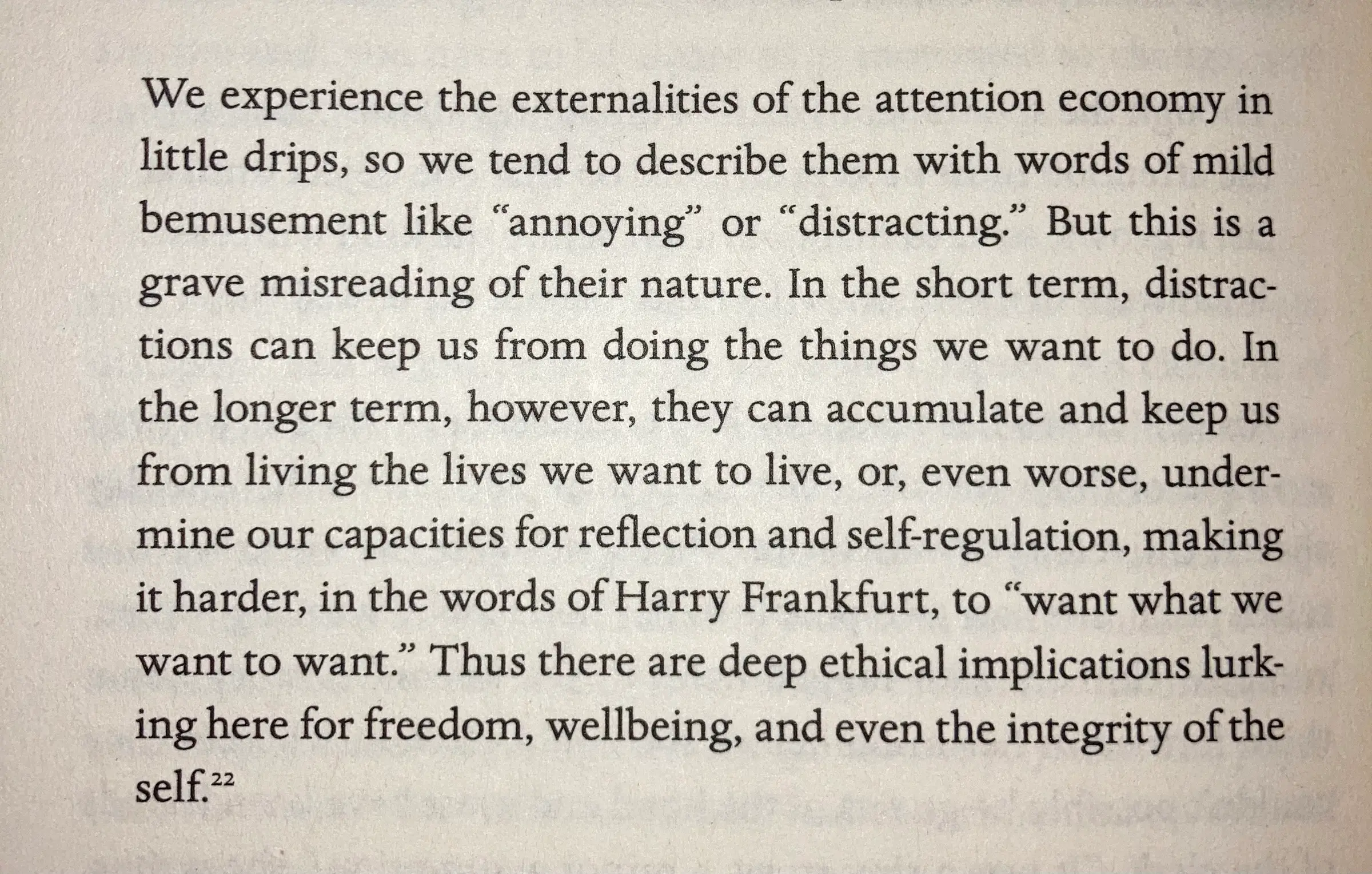

As of 2025, a stamp for a letter costs $0.78 in the United States. Amazon Prime sells items for less than that… with free shipping! Why send a postcard when you can send actual stuff?

I found all items under $0.78 with free Prime shipping — screws, cans, pasta, whatever. Add a free gift note. It arrives in 1 or 2 days. Done.

You’re not only saving money. It’s about sending something real. Your friend gets a random can of tomato sauce with your birthday note attached. They laugh. They remember you. They might even use it!

Source: Riley Walz

The Cost of American Exceptionalism

We all know that what’s going on in the US is pretty terrible. But there remains an underlying assumption that the way that Americans organise their society is in some way better, or more valuable than how things are done in Europe and other OECD nations.

Instead of taking American exceptionalism as our example in the UK, we should be looking to re-integrate with our European neighbours.

America’s problems are solved problems.

Universal healthcare is not some utopian fantasy. It is Tuesday in Toronto. Affordable higher education is not an impossible dream. It is Wednesday in Berlin. Sensible gun regulation is not a violation of natural law. It is Thursday in London. Paid parental leave is not radical. It is Friday in Tallinn, and Monday in Tokyo, and every day in between.

Source: On Data and Democracy

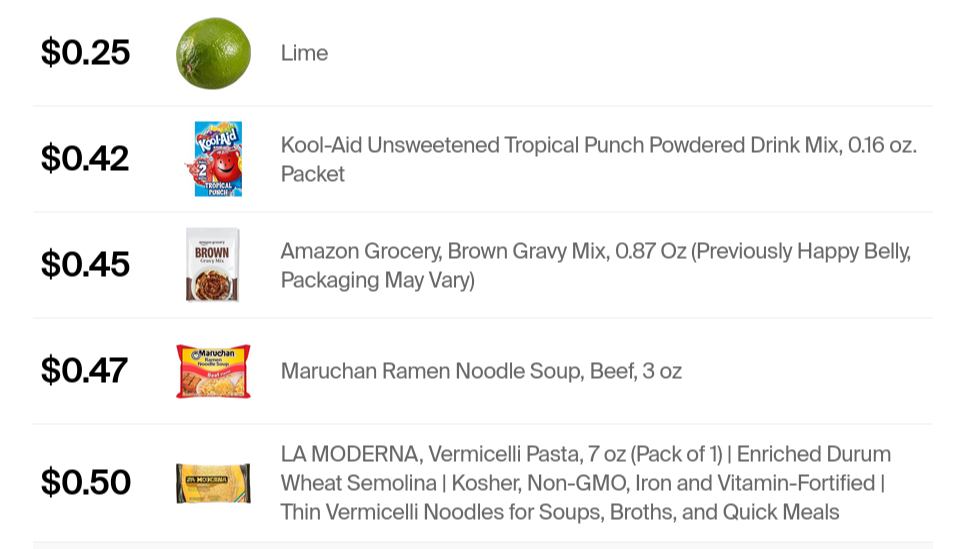

LinkedIf

When I was a boy, I had a poster of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If” on my wall. As a result, I’ve always had a soft spot for it, even though Kipling can be a controversial character.

So I found this parody entitled “LinkedIf” by Jamie Hardesty hilarious. So, so good.

Source: LinkedIn

We will no longer have the conspiracy nonsense about state control

This climbdown was, perhaps, inevitable. Especially given what’s going on in the US, where the Secretary for the Department of Homeland Security has said that citizens need to be ready to show proof of citizenship.

People will still need to prove they have the right to work in the UK, but using digital identification won’t be the only way. I’m pleased, as it will make my work in Scotland around Verifiable Credentials much easier. Perception often trumps fact.

People will still be required to verify their ID digitally, by a process still to be finished, but this could involve existing documents such as a passport. The hope is that this would crack down on illegal working while avoiding the controversy of an in effect compulsory ID system.

It is understood that one of the motivations for the change was to allow people who wanted to use digital ID to do so, while avoiding the PR hurdle of a mandatory element. As one official put it: “We will no longer have the conspiracy nonsense about state control.”

A government spokesperson said: “We are committed to mandatory digital right to work checks. We have always been clear that details on the digital ID scheme will be set out following a full public consultation which will launch shortly.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Tom Radetzki

If execution is no longer the differentiator, what is?

In a post entitled Ideas are cheap, execution is cheaper, Dave Kiss talks about his changing role as a software developer in a world of AI. It’s something I wrote about here. The hard part isn’t coming up with ideas or even shipping them any more; it’s what happens after that. Iteration. Support. Maintenance. Care.

Earlier this week, after switching from Google to Proton and needing an appointment scheduler, I got Perplexity to come up with a Product Reference Document (PRD) after a conversation discussing what I needed. Then I put that into Cursor and about 10 minutes later I had the basis of Scheduler which I’ve released on GitHub.

It needs some tweaking around mail delivery, but it’s running at scheduler.dougbelshaw.com. The hard bit wasn’t the idea, or the execution, but keeping it running, maintaining it, and iterating on new features.

I tweeted about Triage in response to someone saying talented engineers now write the majority of their code with agents. My reply: “What about not writing the code at all?” I described the idea—users report bugs to AI, AI triages and implements, AI opens the PR.

Days later, the same person published an article: “Our AI agent now files its own bug reports.”

They liked my tweet, saw the idea, and shipped it.

I’m not claiming ownership. That’s exactly the point. In a world where execution is trivial, ideas become instantly commodifiable. The moat isn’t “I can build this and you can’t.” The moat can’t be that anymore, because anyone can build anything. The window between sharing an idea and someone else shipping it has collapsed from months to days—sometimes hours.

[…]

If execution is no longer the differentiator, what is?

Speed of iteration matters. Not speed of initial build—everyone has that now. Speed of learning. How fast can you ship, learn from users, and adapt? The teams that win will be the ones that cycle fastest, not the ones that build first.

Taste matters. Knowing what’s worth building. Knowing what to say no to. In a world where you can build anything, the scarcest resource is judgment about what should exist. Most things shouldn’t.

Distribution matters. It always did, but now it matters more. When everyone can build, the only differentiation is who people hear about, who they trust, whose product they encounter first. The network you can tap into for trials and feedback—that’s the real moat.

Problem selection matters. The hardest part of building software was never typing the code. It was figuring out which problems are real, which solutions people will pay for, which bets are worth making. That calculus hasn’t changed. If anything, it’s more important now because the cost of building the wrong thing is lower, which means more wrong things will get built.

The “execution is hard” era trained us to be careful about what we committed to building. That constraint is gone. The new discipline is choosing wisely when you can build anything.

Source: Dave Kiss

Image: Resource Database

Bottom-up (systems) thinking

I have no idea if I’m neurodivergent. I don’t think I’ve got ADHD, and all men are probably on the spectrum somewhere. Who’d want to be neuro_typical_ anyway?

Wwhat I do know i that the neurodiverse people I’ve worked with in my career have been pretty awesome. This post outlines some reasons that neurodivergent brains build better systems. It’s worth a read.

Trait 1: Systems Thinking

Neurotypical people are top-down thinkers. They have a hypothesis first then obtain data to support or disprove the hypothesis.

Neurodivergent people are bottom-up thinkers. They begin collecting relevant data first then form their hypothesis or “big picture” later.

[…]

Trait 2: Hyperfocus and Flow

We live in a distraction economy. Nearly everything in the modern world seeks to rob our focus and divide it among a million shallow things.

Neurodivergent people don’t focus, they obsess. This is a rare skill in these times. I have met neurodivergent people who have created their own programming language and composed and recorded full albums worth of music in just a week.

[…]

Trait 3: Automation Instinct

Manual repetitive process can be extremely disruptive and frustrating for neurodivergent employees.

Imagine that you have the power to type characters into a machine that then does things automatically for you 24/7 at a scale of millions, billions, or just about whatever scale you ask it to. You have that power, and then someone tells you to manually enter numbers that you fetch from one system into a spreadsheet in another system. Once? Fine, there’s always going to be some grunt work. If this becomes the norm though, neurodivergent employees will resent the work.

So what works for neurodivergent workers? The post has a list:

- Remote-first

- Cultural discipline

- Neurodivergent representation

Source: Dr. Josh C. Simmons

Image: Wiki Sinaloa

A deliberate willingness to be helped

I really enjoyed reading this post by Kevin Kelly about hitch-hiking, the kindness of strangers, and, most importantly, the generosity of being willing to be helped.

Kindness is like a breath. It can be squeezed out, or drawn in. You can wait for it, or you can summon it. To solicit a gift from a stranger takes a certain state of openness. If you are lost or ill, this is easy, but most days you are neither, so embracing extreme generosity takes some preparation. I learned from hitchhiking to think of this as an exchange. During the moment the stranger offers his or her goodness, the person being aided can reciprocate with degrees of humility, dependency, gratitude, surprise, trust, delight, relief, and amusement to the stranger. It takes some practice to enable this exchange when you don’t feel desperate. Ironically, you are less inclined to be ready for the gift when you are feeling whole, full, complete, and independent!

[…]

Altruism among strangers, on the other hand, is simply strange. To the uninitiated its occurrence seems as random as cosmic rays. A hit or miss blessing that makes a good story. The kindness of strangers is gift we never forget.

But the strangeness of “kindees” is harder to explain. A kindee is what you turn into when you are kinded. Curiously, being a kindee is an unpracticed virtue. Hardly anyone hitchhikes any more, which is a shame because it encourages the habit of generosity from drivers, and it nurtures the grace of gratitude and patience of being kinded from hikers. But the stance of receiving a gift – of being kinded — is important for everyone, not just travelers. Many people resist being kinded unless they are in dire life-threatening need. But a kindee needs to accept gifts more easily. Since I have had so much practice as a kindee, I have some pointers on how it is unleashed.

I believe the generous gifts of strangers are actually summoned by a deliberate willingness to be helped. You start by surrendering to your human need for help. That we cannot be helped until we embrace our need for help is another law of the universe. Receiving help on the road is a spiritual event triggered by a traveler who surrenders his or her fate to the eternal Good. It’s a move away from whether we will be helped, to how: how will the miracle unfold today? In what novel manner will Good reveal itself? Who will the universe send today to carry away my gift of trust and helplessness?

Source: The Technium

Image: David Guevara

What content are you really trying to provide and how do you get to it?

If you visit dougbelshaw.com it will appear pretty much instantly, no matter what speed of internet connection you’re on. Why? Because it’s 4.9kB in size. Over 3kB of that is the favicon so I could reduce it even further by not having that little ⚡ emoji show up on the web browser tab. But you’ve got to have some flair…

There are sites that are under 512kB in size. That’s easy. You can get sites under 1kB too. But why would anyone care? Well, as this post explains, sometimes accessibility and page speed is a matter of life and death.

We recently passed the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Helene and its devastating impact on Western North Carolina. When the storm hit, causing widespread flooding, it wasn’t just the power that was knocked out for weeks due to all the downed trees. Many cell towers were damaged, leaving people with little to no access to life-saving emergency information.

[…]

When I was able to load some government and emergency sites, problems with loading speed and website content became very apparent. We tried to find out the situation with the highways on the government site that tracks road closures. I wasn’t able to view the big slow loading interactive map and got a pop-up with an API failure message. I wish the main closures had been listed more simply, so I could have seen that the highway was completely closed by a landslide.

[…]

With a developing disaster situation, obviously not all information can be perfect. During the outages, many people got information from the local radio station’s ongoing broadcasts. The best information I received came from an unlikely place: a simple bulleted list in a daily email newsletter from our local state representative. Every day that newsletter listed food and water, power and gas, shelter locations, road and cell service updates, etc.

Limited connectivity isn’t something that only happens during natural disasters. It can happen all the time in our daily lives. In more rural areas around me, service is already pretty spotty. In the past, while working outdoors in an area without Wi-Fi, I’ve found myself struggling to load or even find instruction manuals or how-to guides from various product manufacturers.

Just using Semantic HTML and the correct native elements, we also can set a baseline for better accessibility. And make sure interactive elements can be reached with a keyboard and screen readers have a good sense of what things are on the page. Making websites responsive for mobile devices is not optional, and devs have had the CSS tools and experience to do this for over a decade. Information architecture and content is important to plan and revisit. What content are you really trying to provide and how do you get to it?

Source: Sparkbox

Image: Pierre Borthiry - Peiobty

Celebrating the lesser-known at the Internet Archive

Bryan Alexander, longtime reader of Thought Shrapnel shared this with me. January 1st is known as ‘Public Domain Day’ as new works become freely available as their copyright expires.

This interactive ‘tapestry’ was created by Bob Stein, who is founder and co-director of The Institute for the Future of the Book. It’s worth investigating!

On January 1st people celebrate the books entering the public domain after their copywrights expire. This year, that means books published in 1930. Unsurprisingly people focus on the “famous” titles which this year include As I Lay Dying, The Maltese Falcon, four Nancy Drew titles and Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. I sense that people read the lists and check-off the ones they’ve heard of, but rarely do more. So, I thought it might be interesting to dig a little deeper. Not only is it fun to explore the relatively unknown, I think there’s a lot to be learned by looking at the ways our forebears looked at the world 95 years ago. Public Domain Day is celebrated all over the western world but each country or region has different copyright periods so the newly arrived titles are not the same. This collection is all U.S. based and all the books displayed here are from the Internet Archive.

Source: tapestries.media

The Questions

One of the great things about Are.na is that you find all kinds of links and clips that people have shared. Sometimes, though, you don’t know where they came from, which is the case for this great list of questions.

They’re very pertinent to my life right now, and I should imagine quite a few people at the beginning of a new year.

Source: thorge xyz

Avoiding 'hacklore'

I mentioned a few months ago the hysteresis effect which means there’s always a lag — and sometimes a big lag — between the state of things and our response to it.

Advice around privacy and security is a good example of this. People are often way out date with what constitutes good practice. This open letter from “current and former Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs), security leaders, and practitioners” points to advice to avoid public wifi, never charge from public USB ports, and to regularly ‘clear cookies’ as being pointless.

This constitutes what they call “hacklore” (a blend of “hacking” and “folklore”): modern urban legends about digital safety. It “spreads quickly and confidently… as if it were hard-earned wisdom” but “like most folklore, it isn’t grounded in reality, no matter how plausible it sounds.”

Instead of this hacklore they suggest the following, and have a newsletter which you might want to subscribe to if this piques your interest:

Keep critical devices and applications updated: Focus your attention on the devices and applications you use to access essential services such as email, financial accounts, cloud storage, and identity-related apps. Enable automatic updates wherever possible so these core tools receive the latest security fixes. And when a device or app is no longer supported with security updates, it’s worth considering an upgrade.

Enable multi-factor authentication (“MFA”, sometimes called 2FA): Prioritize protecting sensitive accounts with real value to malicious actors such as email, file storage, social media, and financial systems. When possible, consider “passkeys”, a newer sign-in technology built into everyday devices that replaces passwords with encryption that resists phishing scams — so even if attackers steal a password, they can’t log in. Use SMS one-time codes as a last resort if other methods are not available.

Use strong passphrases (not just passwords): Passphrases for your important accounts should be “strong.” A “strong” password or passphrase is long (16+ characters), unique (never reused under any circumstances), and randomly generated (which humans are notoriously bad at doing). Uniqueness is critical: using the same password in more than one place dramatically increases your risk, because a breach at one site can compromise others instantly. A passphrase, such as a short sentence of 4–5 words (spaces are fine), is an easy way to get sufficient length. Of course, doing this for many accounts is difficult, which leads us to…

Use a password manager: A password manager solves this by generating strong passwords, storing them in an encrypted vault, and filling them in for you when you need them. A password manager will only enter your passwords on legitimate sites, giving you extra protection against phishing. Password managers can also store passkeys alongside passwords. For the password manager, use a strong passphrase since it protects all the others, and enable MFA.

Source: Stop Hacklore! Open Letterwww.hacklore.org/letter

Image: CC BY Robert Lord

Open Infrastructure map

This is fascinating. Both in terms of the macro picture, but also when you zoom in to where you live, to see the hidden infrastructure that literally powers our world.

Source: Open Infrastructure Map

Post-digital authenticity

I agree with Ava, the author of this post, who effectively says that the internet has been stolen from us by Big Tech and people pushing a “post-authenticity” culture. Going back to offline for verification feels good at first, but steals something from those for whom the internet was liberating.

Looking around the internet, it’s clear that digital representations have become cheap, too perfect, and easily fabricated, and the offline world is increasingly the primary source of confirmation.

[…]

Want to know whether someone really studied, wrote that exam, or is a suitable job candidate? Direct interaction, live problem-solving and in-person demonstrations are the way to go now. Claims of expertise, portfolios, blog posts, code projects, certificates, and even academic records can be fabricated or enhanced by AI online.

[…]

We could call this post-digital authenticity. I know that social media platforms are currently pushing a sort of post-authenticity culture instead, where honesty and truth no longer matters and contrived and fabricated experiences for entertainment (ragebait, AI…) get more attention; but I think many, many people are tired of being constantly lied to, or being unable to trust their senses. I assume that the fascination with the totally fake that some people still have now is shortlived.

This step backwards into the offline feels healing at first, but also hurts, in a way. With all the valid criticisms, the internet still was a rather accessible place to finally find out the truth about events, avoid state censorship, and get to know people differently. It was especially good for the people who could not experience the same offline: People in rural areas, disabled and chronically ill people, queer people living far out and away from their peers, and more. It sucks that while others can and will return to a more authentic offline life, the ones left behind in a wasteland of mimicry are the ones who have always been left out.

Source: …hi, this is ava

Image: Igor Omilaev

Humans exhibit analogues of LLM pathologies

Over on my personal blog I published a post today about AGI already being here and how it’s affecting young people. What we don’t seem to be having a conversation about at the moment, other than the ‘sycophancy’ narrative, is why some people prefer talking to LLMs over human beings.

Which brings us to this post, not about the problems about conversing with AI, but applying some of those critiques to interacting with humans. It which should definitely be taken in a tongue-in-cheek way but it does point towards a wider truth.

Too narrow training set

I’ve got a lot of interests and on any given day, I may be excited to discuss various topics, from kernels to music to cultures and religions. I know I can put together a prompt to give any of today’s leading models and am essentially guaranteed a fresh perspective on the topic of interest. But let me pose the same prompt to people and more often then not the reply will be a polite nod accompanied by clear signs of their thinking something else entirely, or maybe just a summary of the prompt itself, or vague general statements about how things should be. In fact, so rare it is to find someone who knows what I mean that it feels like a magic moment. With the proliferation of genuinely good models—well educated, as it were—finding a conversational partner with a good foundation of shared knowledge has become trivial with AI. This does not bode well for my interest in meeting new people.

[…]

Failure to generalize

By this point, it’s possible to explain what happens in a given situation, and watch the model apply the lessons learned to a similar situation. Not so with humans. When I point out that the same principles would apply elsewhere, their response will be somewhere along the spectrum of total bafflement on the one end and on the other, a face-saving explanation that the comparison doesn’t apply “because it’s different”. Indeed the whole point of comparisons is to apply same principles in different situations, so why the excuse? I’ve learned to take up such discussions with AI and not trouble people with them.

[…]

Indeed, why am I even writing this? I asked GPT-5 for additional failure modes and found more additional examples than I could hope to get from a human:

Beyond the failure modes already discussed, humans also exhibit analogues of several newer LLM pathologies: conversations often suffer from instruction drift, where the original goal quietly decays as social momentum takes over; mode collapse, in which people fall back on a small set of safe clichés and conversational templates; and reward hacking, where social approval or harmony is optimized at the expense of truth or usefulness. Humans frequently overfit the prompt, responding to the literal wording rather than the underlying intent, and display safety overrefusal, declining to engage with reasonable questions to avoid social or reputational risk. Reasoning is also marked by inconsistency across turns, with contradictions going unnoticed, and by temperature instability, where fatigue, emotion, or audience dramatically alters the quality and style of thought from one moment to the next.

Source: embd.cc

Image: Ninthgrid

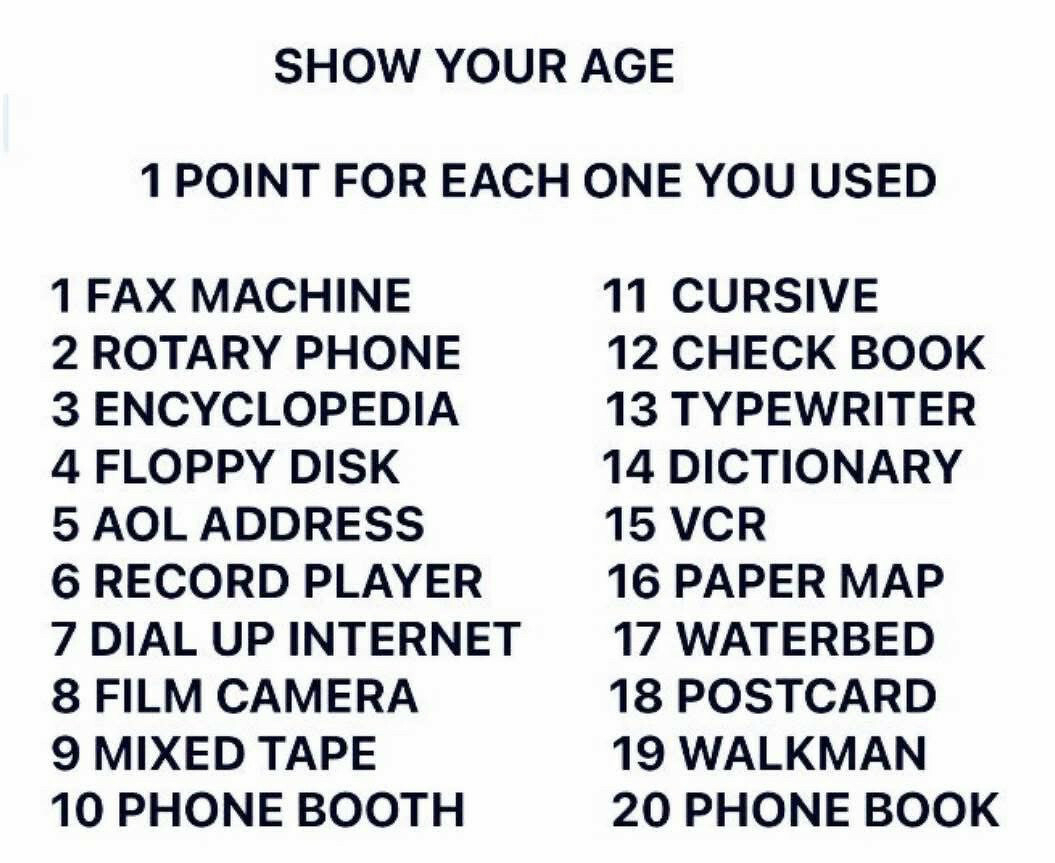

19/20 for me. How about you?

A university degree is now more like a 'visa' than a guaranteed route to professional success

Earlier this week, I published at my newly-revamped personal blog a post entitled Your mental models are out of date. The main thrust of what I was saying was that young people are getting advice from older people whose understanding of the world does not mesh with the way things really are in the mid-2020s.

This article in The Guardian is helpful for understanding the other side of the argument from a policy perspective. My opinion is that as many young people who want to go to university should be able to go, and that it’s the duty of us as a society to enable that to happen as efficiently as possible. Yes, that means that the value of a ‘degree’ as a chunky proxy credential decreases, but that’s why we should have more tailored, up-to-date, granular credentials in any case.

Prof Shitij Kapur, the head of King’s College London, said the days when universities could promise that their graduates were certain to get good jobs are over, in an era where nearly half the population enters higher education.

Kapur said a university degree is now more like a “visa” than a guaranteed route to professional success, a reflection of the shrinking graduate pay premium and the increased competition from AI and other graduates from around the world.

“The competition for graduate jobs is not just all because of AI filling out forms or AI taking away jobs. It’s also because of the stalling of our economy and causing a relative surplus of graduates. So the simple promise of a good job if you get a university degree, has now become conditional on which university you went to, which course you took,” Kapur said.

“The old equation of the university as a passport to social mobility, meant that if you got a degree you were almost certain to get a job as a socially mobile citizen. Now it has become a visa for social mobility – it gives you the chance to visit the arena that has graduate jobs and the related social mobility, but whether you can make it there is not a guarantee.”

[…]

Figures from the Department for Education show that England’s graduates still enjoy higher rates of employment and pay than non-graduates, although the real earnings of younger graduates have been stagnant for the past decade. Kapur points out that the national economy’s slow growth coincided with England’s introduction of £9,000 tuition fees and student loans in 2012, making it “the worst possible time” to transition to individual student loans.

In 2022, Kapur wrote a gloomy discussion of UK higher education that described a “triangle of sadness” between students burdened with debt and pessimistic prospects, a government that used inflation to cut tuition fees, and overstretched university staff trapped in between.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Christian Lendl