Your actions follow your self-beliefs

Something I say semi-regularly to friends and family is “people can only treat you the way you let them.” Inspired by quotations from Seth Godin and James Clear, this post is the other side of the coin. It’s about the way you treat yourself.

This year, I’ve had tests for a whole range of things. One by one I’ve discovered there’s nothing wrong with the structure of my heart, with my lungs, thyroid, adrenal glands—and I’m not anaemic. As the year has gone on, I’ve gotten slightly better, and then a lot better.

I’m still not fully right, as I can’t run or do some of the more intense physical things I used to do. But I’ve got a new self-image, one that’s perhaps more appropriate to the age I am. Not that I should expect less of myself, but that I should expect different things.

Your actions follow your self-beliefs.

If you identity as a failure, incapable of achievement, unfit, unlovable, destined to play a bit-part role in your own story, then by heck no matter how much willpower you put in to push that boulder up the hill, it will return to its place.

But there’s a way through: every action you take is a vote for who you wish to become. Every day you wake up, look your old identity in the eye and say “thanks for your service, but you’re not needed around here anymore,” step forward and lean in, is a day your new identity is built.

It takes time. You have to actually want it. You have to choose to adopt a new mindset. Rome wasn’t built in a day. But it comes, a little like how Hazel Grace Lancaster describes falling in love in The Fault In Our Stars: “slowly, and then all at once.”

The path is there, should you choose.

Source: @fredrivett

Image: chloe combs

Each of us is part of an interpretive community that gives us a particular way of reading a text

I’m not sure why I’m sharing this post other than it reaffirms my commitment to stay off social networks such as X, Instagram, and TikTok. The suggestions towards the end (use RSS! embrace federated social networks! switch to Linux/GrapheneOS/Signal!) I’ve already embraced, but the thing is that unless a significant minority of people do this, it makes very little difference on the rest of the world, which is effectively powered by algorithm.

Literary theorist Stanley Fish argued that we as individuals interpret any given text (in this case, social media content) “because each of us is part of an interpretive community that gives us a particular way of reading a text.” That interpretive community usually isn’t there when we are fed what the algorithm thinks we’ll consume. We may share something thinking that people like us will see it share their opinions. However, because of the way that algorithms work, engagement is the main driver of a post’s visibility; so here comes 10 million people who have no clue of the context on that thought you shared about your niche interest.

Suddenly your post is full of over-the-top jokes and non-content-related quips from members of a completely random mix of audiences. As the algorithm prioritizes engagement, your post’s new mixing pot of clueless audiences outnumbers the genuinely-interested audience of your own niche corner of the internet (if that even exists anymore), and they comment about everything BUT the content.

Source: tékhnē.dev

Image: Kevin Grieve

I’m pretty confident you only need two things. Feedback and humility, and they work best together.

I was listening to a podcast recently about the concept of “limitarianism” entitled Imagine there’s no billionaires in which the political philosopher Ingrid Robeyns laid out the ways in which, truly, every billionaire is a policy failure. Nobody accumulates great wealth without some sort of dependency on society — whether that’s tax breaks, lack of worker regulation, or some other “pro business” (but anti-society) law.

The truth is that people don’t achieve success by themselves. Luck, nepotism, and cultural capital play a huge part in what most people would deem success. That’s not to say that it’s not possible to increase your serendipity surface, though.

What I like from this post by Josh Swords is that he centres agency in his “career advice” which is achieved by seeking feedback and getting better demonstrating humility and working in the open. Powerful stuff.

I’m pretty confident you only need two things. Feedback and humility, and they work best together. Feedback shows you what to work on, and humility lets you actually hear it.

So find your weakest discipline and work on that. The fastest way is to get feedback from someone you admire and then act on it. Don’t wait for the perfect plan, doing something is almost always better than doing nothing.

Find a mentor, be a mentor. Lead a project, propose one. Do the work, present it. Create spaces for others to do the same. Do whatever it takes to get better.

And do it in the open. A common mistake is assuming work speaks for itself. It rarely does.

But all of this requires maybe the most important thing of all: agency. It’s more powerful than smarts or credentials or luck. And the best part is you can literally just choose to be high-agency. High-agency people make things happen. Low-agency people wait. And if you want to progress, you can’t wait.

Source: people, ideas, machines

Image: CC BY-NC Focal Foto

"You know what this needs? Less safety testing and more venture capital!"

Collected at this site are some absolutely awful uses of AI. Not only in terms of people misunderstanding what technology can and can’t do, but just really bad ideas. For example, Airbnb hosts fraudulently claiming damage via AI-doctored photos, users being able to hack McDonald’s systems by asking for the password, and Microsoft providing ‘therapy’ via LLMs for laid-off workers.

Named after Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, the original Darwin Awards celebrated those who “improved the gene pool by removing themselves from it” through spectacularly stupid acts. Well, guess what? Humans have evolved! We’re now so advanced that we’ve outsourced our poor decision-making to machines.

The AI Darwin Awards proudly continue this noble tradition by honouring the visionaries who looked at artificial intelligence—a technology capable of reshaping civilisation—and thought, “You know what this needs? Less safety testing and more venture capital!” These brave pioneers remind us that natural selection isn’t just for biology anymore; it’s gone digital, and it’s coming for our entire species.

Because why stop at individual acts of spectacular stupidity when you can scale them to global proportions with machine learning?

Source: AI Darwin Awards

Image: IceMing & Digit

AI and the future of education: disruptions, dilemmas and directions

A few months ago, UNESCO put a call out under the title AI and the future of education: disruptions, dilemmas and directions. I asked a few talented people I know if they would be interested in working together on a response. In the end, we submitted six separate pieces and then ran an online roundtable. You can see the results here

We published our versions as, after a couple of months, we hadn’t heard anything back from UNESCO. However, last week we heard that they hadn’t included our pieces in the publication because we’d published them. Ah well, they said that they might put together a web page showcasing what we’ve done.

I’m looking forward to reading some of the contributions, which seem to come from quite diverse sources.

This anthology explores the philosophical, ethical and pedagogical dilemmas posed by disruptive influence of AI in education. Bringing together insights from global thinkers, leaders and changemakers, the collection challenges assumptions, surfaces frictions, provokes contestation, and sparks audacious new visions for equitable human-machine co-creation.

Covering themes from dismantling outdated assessment systems to cultivating an ethics of care, the 21 think pieces in this volume take a step towards building a global commons for dialogue and action, a shared space to think together, debate across differences, and reimagine inclusive education in the age of AI.

Source: UNESCO

Image: Yutong Liu & Digit

The hysteresis effect means that practices are always liable to be objectively adjusted too late

I learned the word hysteresis only recently after having a heat pump fitted Chez Belshaw. In that context, it refers to the difference in temperature at which the system turns on and off, creating a lag in response to temperature changes. That’s a good thing in this context, as it helps prevent rapid cycling of the heat pump — making the system more stable and improving overall efficiency.

Hysteresis in other contexts can be less useful, though. A lag in response to changes can be problematic when it comes to technological change affecting certain sectors, for example knowledge workers. I don’t subscribe to Venkatesh Rao’s Contraptions newsletter, but just the part publicly available is thought-provoking.

Inevitably, those who have financial and cultural capital usually catch up and re-assert their authority and dominance. I’ve seen this in practice when universities were threatened by innovations in MOOCs and Open Badges. It was the “end of universities,” apparently. But, of course, already being in a dominant position, and thanks to the catalyst of a global pandemic, we now have unis with more online than in-person students, issuing microcredentials by the million.

I’m not saying that there won’t be ‘casualties’ and that there won’t be new ways of stratifying society. I think we’re already starting to see some of that in terms of text-based communication being a lot less dominant as a means of social communication. I’m just saying that when you’ve got a lot of financial and cultural capital, you have to do a particularly bad job to squander it entirely.

The mark-maker class lives in the gap between the signs and the systems. They comprise those who produce, coordinate, teach, and manage the functioning of symbolic order on the one hand, and those who remix, stylize, dream, and craft the cultural tones in which life is rendered bearable, on the other. These are not two classes, but one diffuse stratum, braided of institutional and aesthetic lives, of spreadsheets and metaphors.

Once insulated by the seeming security of letters and credentials, the mark-makers now find themselves in hysteresis: lagging in the face of an accelerating world that no longer waits for meaning to catch up.

[…]

Bourdieu teaches us that when the field moves faster than the habitus can adapt, a lag sets in. “The hysteresis effect,” he writes, “means that practices are always liable to be objectively adjusted too late, and that habitus tends to lag behind the changes in the field.” This lag is not benign. It is lived as confusion, disorientation, ridicule, even rage. What was once a reliable feel for the game becomes a stale reflex. The mark-makers—who for decades moved with the grain of modern institutions—now find their instincts misfiring. Their ways of knowing, their modes of speaking, their cultivated manners now appear quaint, procedural, indulgent. They are mocked by populists as condescending, and by radicals as co-opted. Worse, they are made redundant by machines that now wield, with eerie fluency, the very tools they mastered.

Source: Contraptions

Image: Logan Voss

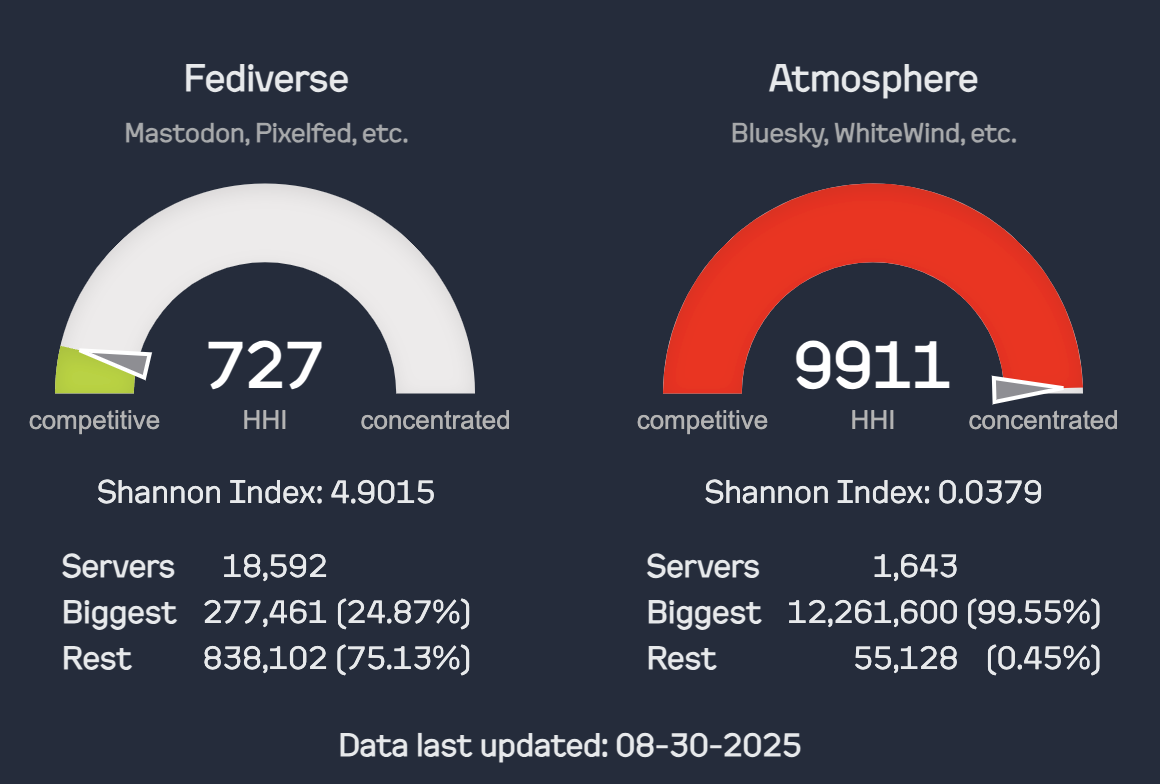

Are we decentralised yet?

One of the things that I see on repeat in discussions around federated social networks is how decentralised Bluesky is compared with, say, Mastodon. What I like about this site is that a) it’s visual, and b) it tries to use some kind of scientific rationale to compare the two.

So yes, while you can say that Bluesky is decentralised in theory, in practice it’s very much not. Yet, anyway.

This site currently measures the concentration of user data for active users: in the Fediverse, this data is on servers (also known as instances); in the Atmosphere, it is on the PDSes that host users' data repos. All PDSes run by the company Bluesky Social PBC are aggregated in this dataset, since they are under the control of a single entity. Similarly, mastodon.social and mastodon.online are combined as they are run by the same company.

A note about the measurement:

The Shannon Index is an entropy-based measure used in ecological studies. It is computed the same as Shannon entropy using the natural log: the negative sum over all servers of the “market share” times the log of the market share. Lower values indicate lower entropy (a high concentration of one species), while higher values indicate a more even population. In this context, the maximum value is the number of servers, which would mean that all servers have equal population.

Source: Are We Decentralized Yet?

A list of intentions; a poem; the “I want” song; not a bucket list——

I love this idea, a list of wants which, over time, accrete into a kind of “song” rather than a bucket list. Dom Corriveau (who hosts his website on an old Google Pixel 5!) stole the idea from Keenan who, in turn, got the idea from Katherine Yang. Interesting people all.

Source: Dom Corriveau

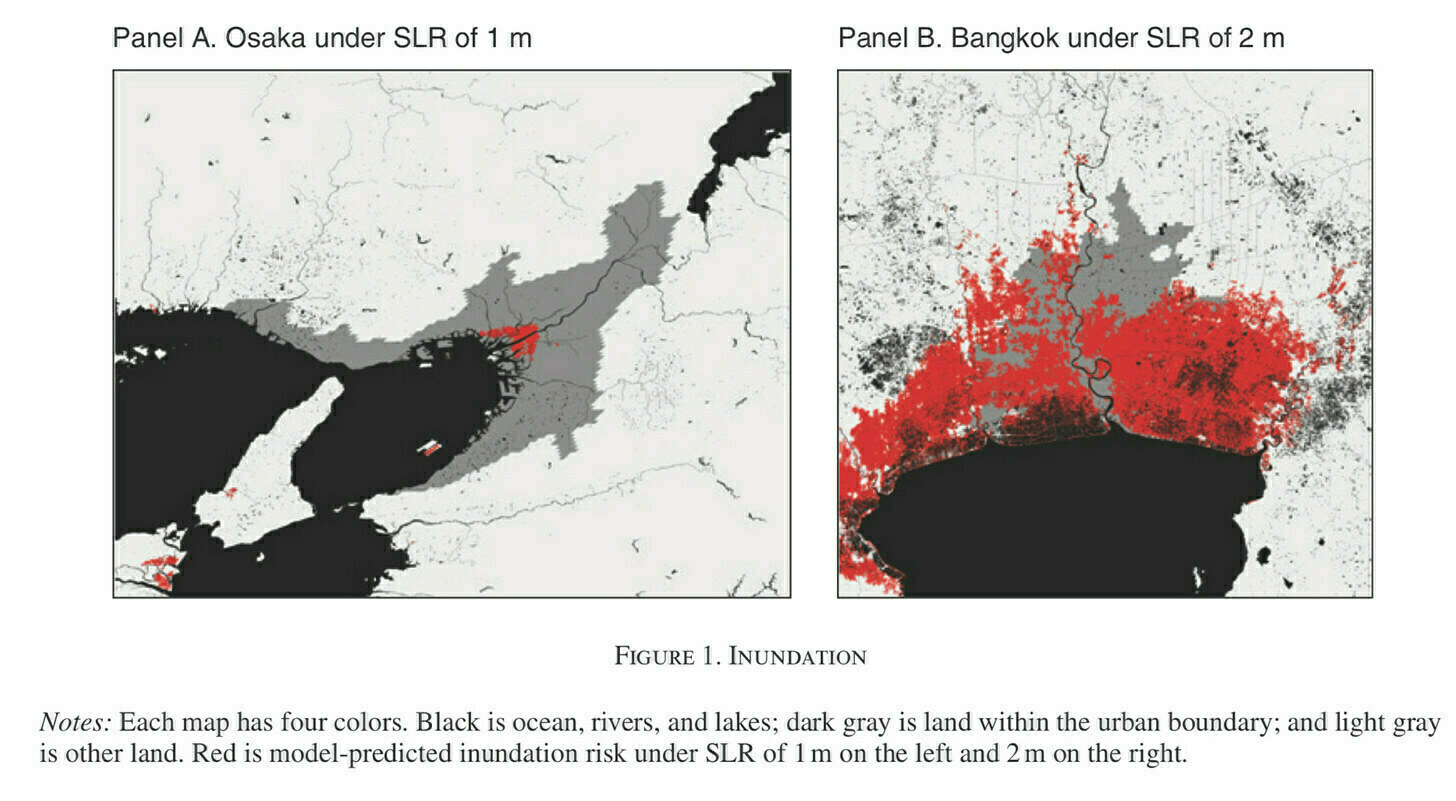

"Zurich doesn’t want to pool with Jakarta"

In addition to his Just Two Things blog, futurist Andrew Curry also writes at The Next Wave on “futures, trends, emerging issues and scenarios.” In this post which cites investment writer Joachim Klement, Curry talks about sea level rise, with 1.5m being the tipping point. This"sounds fine in theory since the base case IPCC projections are for around a one metre increase by 2100," but that “doesn’t allow for subsidence (often caused by water extraction), or the possibility of cascading climate change.”

The interesting bit for me, though, was the section he entitles “moral hazards” which relate to insurance and government intervention. Basically, the stronger you make coastal defences, the more likely people are to live there.

Hsiao has also done more specific work on Jakarta, which experiences frequent flooding. There are some interesting conclusions here, broadly that a strong government commitment to sea defences (in Jakarta’s case a sea wall) creates a moral hazard, because it

attracts coastal residents, slows inland migration, and lowers the incentives for inland development. The consequence is continued spending on coastal defense and large damages should it fail.

Insurance doesn’t work because places that don’t flood don’t want to pool with places that do (“Zurich doesn’t want to pool with Jakarta”). Alternatives that might place more of the financial burden on people who choose to live in coastal areas might work, but is open to political lobbying. And once you’ve decided to go with sea defences, and people decide to live behind them, you face political pressure to keep on strengthening the sea defences.

Source: The Next Wave

A remarkable 45% increase in solar capacity

While we in the UK have at least one major political party vowing to extract all of the oil and gas out of the North Sea, China has met its renewable energy goals five years early.

Again, while we have arguments about “net zero” and the aesthetics of solar farms, this summer was the hottest on record and hot homes are making children sick. Meanwhile, China is covering entire mountain ranges in solar panels.

It’s a climate emergency. We should act like it.

China broke its own renewable energy record once again in 2024, installing 80 gigawatts (GW) of wind capacity and 277 GW of solar capacity, according to the National Energy Administration, as reported by Recharge News. This marks an impressive 18% growth in wind capacity, now totalling 520 GW, and a remarkable 45% increase in solar capacity, which has reached 890 GW. Combined, these achievements fulfil the 1.2 terawatts (TW) renewable energy capacity target set by President Xi Jinping in 2020 – a goal originally intended for 2030.

[…]

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has previously pointed to China’s advancements as a key factor in keeping the global goal of tripling renewable power capacity by 2030 within reach. Despite ongoing construction of new coal-fired power plants, China’s total power generation saw a nearly 15% increase in 2024, reaching 3.35 TWh.

Source: The Renewable Energy Institute

Image: The Independent

From misdiagnosis and error to unequal access to care

I am in agreement with this article in The Guardian by Charlotte Blease, a researcher at Harvard Medical School and author of the forthcoming book Dr Bot: Why Doctors Can Fail Us – and How AI Could Save Lives. Her point is that while AI might not be perfect, neither are doctors, and it can definitely speed up and help with diagnoses.

Personally, I’m now 7.5 months into trying to get a diagnosis for symptoms I started experiencing on January 15th of this year. It’s the nature of medicine to do tests and rule things out, but a combination of NHS resourcing and (some) health professionals' attitudes have made the experience sub-optimal.

For example, when presenting at A&E thinking I was having a heart attack, I had an echocardiogram followed by a doctor taking me into a side room and somewhat aggressively asking me why I was there. When a GP found out that I’m vegetarian, he suggested I start eating meat — even though it had nothing to do with the issue at hand. I’ve been waiting almost six weeks for a urine test result.

So, I’ve been supplementing the information I get from health professionals and via the NHS app with asking LLMs (usually Perplexity or Lumo) about what my test results might mean, and what else might be causing the symptoms. It’s given me a list of things to ask doctors, nurses, and those performing tests, and it’s helped me know what kinds of things I should be avoiding — other medications, supplements, food, drinks, activities, etc.

Obviously, this needs to be done with huge amounts of safeguards and guardrails in place. But not to use technology which may prove useful at scale? I think that’s irresponsible.

Given that patient care is medicine’s core purpose, the question is who, or what, is best placed to deliver it? AI may still spark suspicion, but research increasingly shows how it could help fix some of the most persistent problems and overlooked failures – from misdiagnosis and error to unequal access to care.

As patients, each of us will face at least one diagnostic error in our lifetimes. In England, conservative estimates suggest that about 5% of primary care visits result in a failure to properly diagnose, putting millions of patients in danger. In the US, diagnostic errors cause death or permanent injury to almost 800,000 people annually. Misdiagnosis is a greater risk if you’re among the one in 10 people worldwide with a rare disease.

[…]

Medical knowledge also moves faster than doctors can keep up. By graduation, half of what medical students learn is already outdated. It takes an average of 17 years for research to reach clinical practice, and with a new biomedical article published every 39 seconds, even skimming the abstracts would take about 22 hours a day. There are more than 7,000 rare diseases, with 250 more identified each year.

In contrast, AI devours medical data at lightning speed, 24/7, with no sleep and no bathroom breaks. Where doctors vary in unwanted ways, AI is consistent. And while these tools make errors too, it would be churlish to deny how impressive the latest models are, with some studies showing they vastly outperform human doctors in clinical reasoning, including for complex medical conditions.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Alan Warburton, Better Images of AI

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 31st August 2025

This is the last week of Thought Shrapnel being in “low-power mode” over the summer. Please find 10 interesting things with minimal commentary ☀️

Image CC BY-NC-ND su-lin

- 99 Problems: The Ice Cream Truck’s Surprising History (Longreads) — “The Glasgow Ice Cream Van Wars sound like they had all the elements of a cozy crime novel, but the reality was very different. The city’s Serious Crime Squad was dispatched to investigate and stop the fighting, but quickly became the object of derision, renamed by the locals as the Serious Chimes Squad, thanks to their inability to apprehend the perpetrators.”

- We must fight age verification with all we have (User Mag) — “Age verification, like book bans and obscenity laws, will not be narrowly used to prevent access to pornography–it will be used to “legislate morality,” control access to information and limit people’s freedom to self-manage their health and family well-being according to their own morals.”

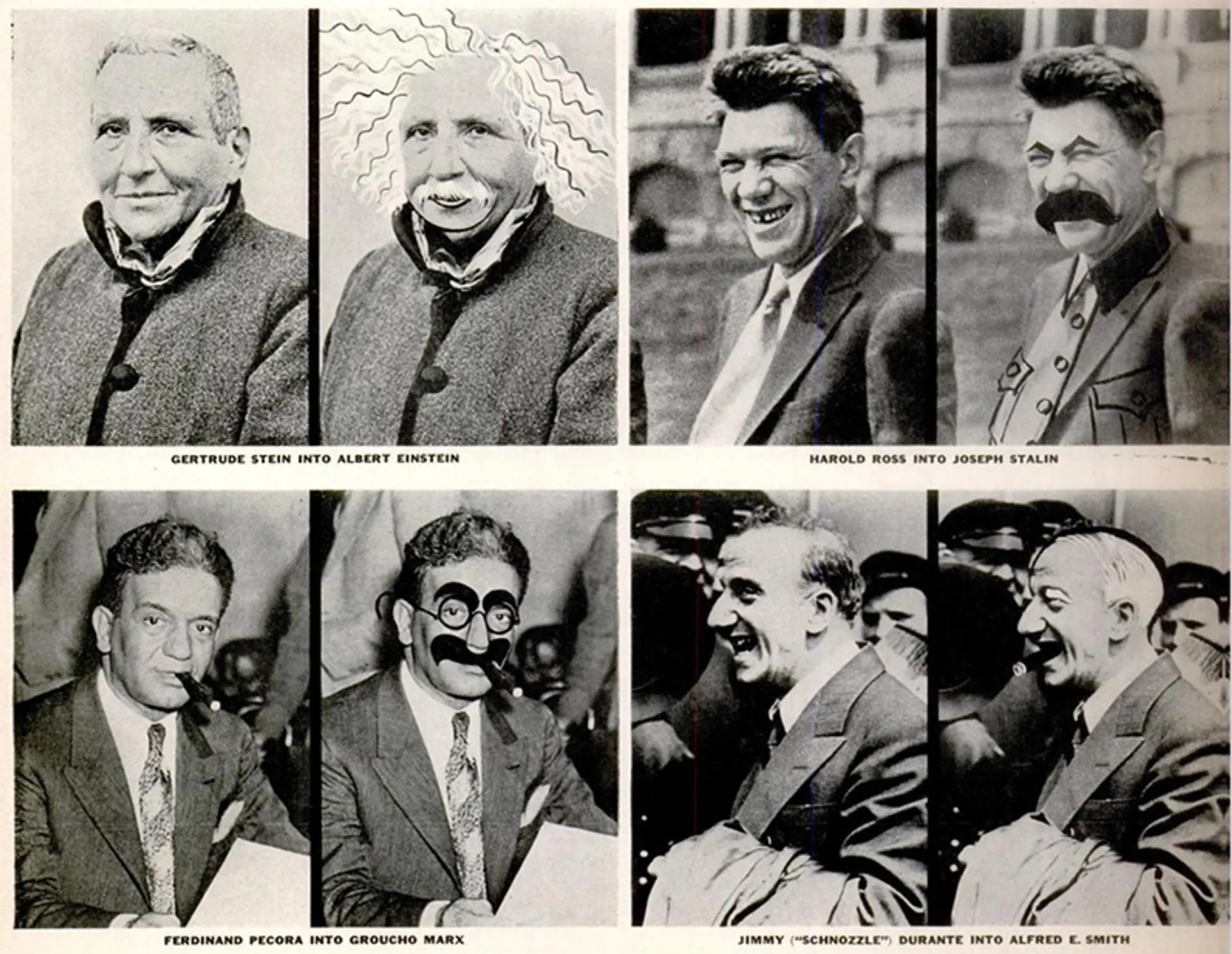

- A new personality type - ‘Otrovert’ - is here to make life even more confusing (GQ) — “‘Otrovert’ – coined this year by New York psychiatrist Dr. Rami Kaminski – describes people who are averse to communing with groups, a bit like Groucho Marx who famously refused to join a club that would have him as a member (it seems the term “Marxist” was already taken). Other characteristics of otroverts include being an ‘original thinker’, ‘valuing deep connections’ and preferring ‘authenticity over conformity. If that sounds relatable, why not join the club? Erm. Maybe not.”

- The ROI of exercise (Herman’s blog) — “It’s well understood that a good exercise routine is a mixture of strength, mobility, and cardio; and is performed at a decent intensity for 2-4 days a week for at least 45 minutes…. This totals about 3 hours a week, or 156 hours per year. If we extrapolate that over an adult lifetime, that’s about 8,500 hours of exercise, or about a year of solid physical activity…[O]ver a lifetime, one full year of exercise leads to 10 full years of extra life. That’s a 1:10 return on investment! So even without any of the additional benefits… this is still one of the best investments you can make.”

- Are Marathon Runners More Likely to Get Cancer? (VICE) — “It all started when Dr. Timothy Cannon, an oncologist at Inova Schar Cancer Institute, noticed something off. Three of his patients, all under 40, were super-fit endurance athletes. They didn’t drink. They didn’t smoke. One was vegan. Yet all had advanced colon cancer, and none of the usual risk factors. So, he turned this mystery into a research study.”

- Writing with LLM is not a shame. An essay about transparency on AI use. (reflexions) — “I think we fell in a ethical fallacy, in a way, with the emergence of a new tech. Even if we compare LLM with other techs, we do not have the same ethics requirements against LLM. Some might say we have to because ELM can generate much more than previous techs but we are falling again in the same reasoning trap.”

- Britain leads the world in a new global business—a criminal one (The Economist) — “Britain accounts for 40% of phone thefts in Europe… British thieves’ favoured method is to approach from behind on an electric bike, grab an unlocked phone and put it in a “Faraday bag” to prevent tracking; most of the nicked phones end up in China. Meanwhile, around 130,000 cars were stolen in Britain last year, a rise of 75% in a decade. SUVs are popular targets, for export to the Gulf and Africa, where they can handle poor roads.”

- We Are Still Unable to Secure LLMs from Malicious Inputs (Schneier on Security) — “This kind of thing should make everybody stop and really think before deploying any AI agents. We simply don’t know to defend against these attacks. We have zero agentic AI systems that are secure against these attacks. Any AI that is working in an adversarial environment—and by this I mean that it may encounter untrusted training data or input—is vulnerable to prompt injection. It’s an existential problem that, near as I can tell, most people developing these technologies are just pretending isn’t there.”

- Reform and the UK press (mainly macro) — “The recent coverage of immigration and asylum in the right wing press has been almost apocalyptic. They have been hyping small demonstrations as if they were indicators of impending national unrest, and the broadcast media has largely followed their lead. The recent celebration by the Mail, Sun and Telegraph of someone who pleaded guilty to inciting racial hatred makes “Hurrah for the Blackshirts” sound rather tame. We have reached the point where a majority of the print media are in effect encouraging civil unrest and racial hatred, yet thanks to political short termism this press remains essentially unaccountable for their behaviour.”

- The great university rip-off (The New World) — “Among dozens of my friends leaving university this year, only three are heading straight into employment. The rest are either going on to further study or taking a gap year before doing so – in their own words, to avoid the inevitable hellscape of the grad job market. For those of us who have braved the post-university job application humiliation ritual, we know we should be grateful to even get a rejection letter, and to try not to have a breakdown when our parents send us 8,000 articles about graduates on universal credit or AI replacing interns.”

👋 See you next week!

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 24th August 2025

Thought Shrapnel is in “low-power mode” over the summer. Please find 10 interesting things with minimal commentary ☀️

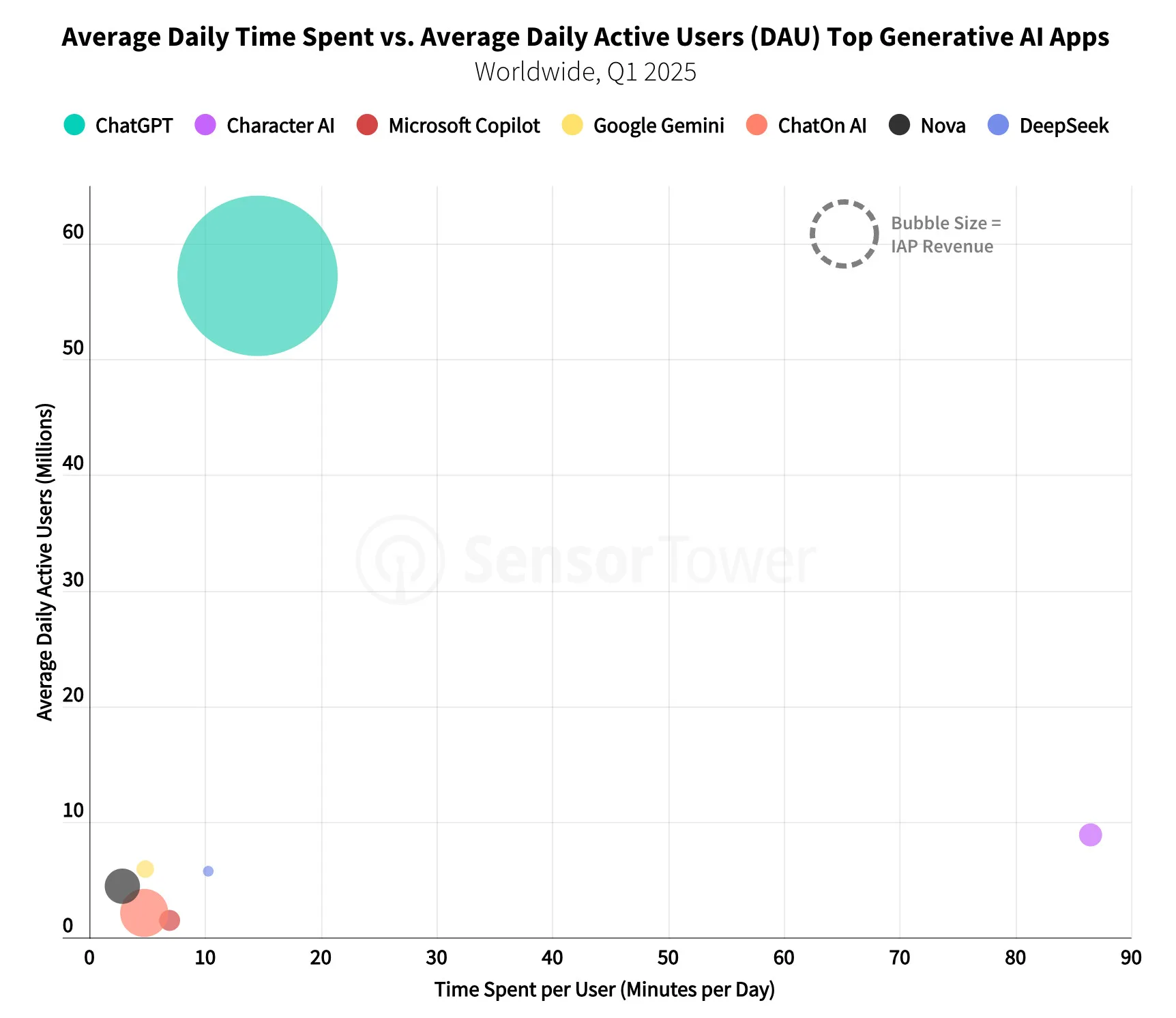

- 4o-4 Not Found (thejaymo) — “Looking closer, 72% of Character.AI’s users are female. Which suggests the rug-pull of 4o more widely may be less a sad incel AI girlfriend story and more an AI boyfriend apocalypse.

- Review of Anti-Aging Drugs (Aging Matters) — “My favorites from this list are Melatonin, Berberine, NAC, Rapamycin, and Selegiline. I can recommend the first three unequivocally. Rapamycin has down sides that you should consider, and Selegiline has effects on mood and energy that you may like or dislike. Personally, I take a variety of anti-inflammatory supplements, and I’m glad to have an excuse to eat dark chocolate.”

- Digital Sovereignty Index (Nextcloud) — “Whether it’s about protecting sensitive data, avoiding vendor lock-in or ensuring democratic control over infrastructure, the debate around digital sovereignty is gaining momentum. But how sovereign is a country’s digital infrastructure in practice?”

- Porn censorship is going to destroy the entire internet (Mashable) — “The stated reason behind these laws is to “protect children.” But as journalist Taylor Lorenz pointed out, in the UK, age verification is already preventing children from accessing vital information, such as about menstruation and sexual assault.”

- Sunny Days Are Warm: Why LinkedIn Rewards Mediocrity (Elliot C Smith) — “The vast majority of it falls into Toxic Mediocrity. It’s soft, warm and hard to publicly call out but if you’re not deep in the bubble it reads like nonsense. Unlike it’s cousins ‘Toxic Positivity’ and ‘Toxic Masculinity’ it isn’t as immediately obvious. It’s content that spins itself as meaningful and insightful while providing very little of either. Underneath the one hundred and fifty words is, well, nothing. It’s a post that lets you know that sunny days are warm or its better not to be a total psychopath. What is anyone supposed to learn from that.”

- The End of Handwriting (WIRED) — “But if kids always have access to devices, does it really matter whether they can write with their hands? Yes and no. If the past few years of digital nomad work and vibe coding have taught us anything it’s that, professionally, handwriting may not be all that necessary in a lot of fields. The problem is that learning handwriting might be necessary to learn everything else. “We don’t yet know what we are losing in terms of literacy acquisition by de-emphasizing handwriting fluency,” Ray says.”

- ‘A climate of unparalleled malevolence’: are we on our way to the sixth major mass extinction? (The Guardian) — “It turns out that there are only a few known ways, demonstrated in the entire geologic history of the Earth, to liberate gigatons of carbon from the planet’s crust into the atmosphere. There are your once-every-50m-years-or-so spasms of large igneous province volcanism, on the one hand, and industrial capitalism, which, as far as we know, has only happened once, on the other.”

- Why I’m all-in on Zen Browser (Ben Werdmuller) — “So I was pleased to rediscover Zen Browser, which has improved in leaps and bounds since I last tried it. It has a very Arc-inspired UI that gets out of your face quickly, with all the customization and keyboard shortcuts you’d expect from something built on top of Firefox. I use vertical tabs in a sidebar that auto-hides, and I can navigate just as smoothly as I ever did with Arc.”

- Changes Coming to Higher Ed (Hybrid Horizons) — “Some may not land as written; timelines slip, context matters, contexts change, things shift and people can surprise us. Still, read this as a calm, plain-spoken brief about potential shifts coming in the sector.”

- The circular economy could make demolition a thing of the past – here’s how (The Conversation) — “This paradigm shift – from a single-use mindset to one of “reduce, reuse, recycle” – is already common in other fields. It is now starting to take hold in construction through various global initiatives that seek to integrate these concepts into safer, more sustainable and more durable buildings. They show how this can be achieved through conscious design, based on concepts such as modularity and standardisation.”

👋 See you next week!

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 17th August 2025

Thought Shrapnel is in “low-power mode” over the summer, sharing 10 interesting things with minimal commentary ☀️

- Witty wotty dashes (Aeon) — “Because of its radical openness to difference, the doodle tends to function as a kind of meta-aesthetic attuned to containing a network of ambivalent affects and fleeting everyday aesthetic experiences that become increasingly common in the 20th century.”

- A moment that changed me: I resolved to reduce my screen time – and it was a big mistake (The Guardian) — “[R]educing my screen time had become its own form of phone addiction. Rather than escaping the need to seek validation from strangers online, I had happened upon a new way to earn their approval.”

- Chatbots Can Go Into a Delusional Spiral. Here’s How It Happens. (The New York Times) — “Sycophancy, in which chatbots agree with and excessively praise users, is a trait they’ve manifested partly because their training involves human beings rating their responses.”

- How to not build the Torment Nexus (Mike Monteiro’s Good News) — “As industries mature, they tend to get a little boring. And as industries age, and start seeing their own collapse over the horizon, they tend to get… defensive. Bitter. Conservative… Tech, which has always made progress in astounding leaps and bounds, is just speedrunning the cycle faster than any industry we’ve seen before.”

- System Font Stack — “Webfonts were great when most computers only had a handful of good fonts pre-installed. Thanks to font creation and buying by Apple, Microsoft, Google, and other folks, most computers have good—no, great—fonts installed, and they’re a great option if you want to not load a separate font.”

- Signal boss: ‘disturbing’ laws show the UK doesn’t understand tech (The Times) — “She says that one of the “most pernicious and alarming” problems is that if a company accepts a “technical capability notice”, it is prohibited from informing users. The upshot: “We don’t know [if any] other company has received one of those notices and responded by rolling over.” Whittaker says Signal has not received one, but that the company would sooner “leave” the UK than comply.”

- Welcome to the Cosmopolis (Contraptions) — “In brief, new technologies induce new normals through protocolization of what is initially a weird and scary sort of monstrousness irrupting across a frontier. Beyond that frontier lies a new kind of territory, a new kind of “soil” on which societies can be built.”

- Funding Open Source like public infrastructure (Dries Buytaert) — “Governments already maintain roads, bridges, and utilities, infrastructure that is essential but not always profitable or exciting for the private sector. Digital infrastructure deserves the same treatment. Public investment can keep these core systems healthy, while innovation and feature direction remain in the hands of the communities and companies that know the technology best.”

- “Privacy preserving age verification” is bullshit (Pluralistic) — “NERD HARDER! is the answer every time a politician gets a technological idée-fixe about how to solve a social problem by creating a technology that can’t exist. It’s the answer that EU politicians who backed the catastrophic proposal to require copyright filters for all user-generated content came up with, when faced with objections that these filters would block billions of legitimate acts of speech.”

- The Logic of the ‘9 to 5’ Is Creeping Into the Rest of the Day (The Atlantic) — “One way to look at 5-to-9 videos is as the product of people trying to make the most of the leisure time they have… But in attempting to take control back from their jobs, many 5-to-9 video creators end up reproducing a version of the thing they are trying to distance themselves from. If you clock out, go home, and continue checking things off a list, you haven’t really left the values of work behind.”

👋 See you next week!

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 10th August 2025

That’s right, Thought Shrapnel continues in “low-power mode” over the summer, so I’ll continue to share 10 interesting things but provide minimal commentary ☀️

- Human speech may have a universal transmission rate: 39 bits per second (Science) — As someone who has enjoyed and endured many conference presentations in my time, this is very interesting to me. “No matter how fast or slow, how simple or complex, each language gravitated toward an average rate of 39.15 bits per second.”

- Tuition fees are rising again and nobody is happy – it’s time to actually fix our broken university sector (The Guardian) — A short, well-written piece by Zoe Williams about the parlous state of Higher Education. Depending on his results next week, hopefully my son is heading off to a university which will still exist in three years' time…

- Marking the Government’s homework on public sector AI (imperfect offerings) — Helen Beetham with a lengthy analysis of what’s going on in the UK with relation to AI, which is possibly best summarised by her withering put down of the memoranda of understanding the government has signed with Google and Microsoft, respectively, as “a cute name for a declining world power signing its assets over to the new ones.” Mexit, not Brexit, is the new priority for the UK (The Register) — Related to the above, although to do with Microsoft licenses rather than AI, Rupert Goodwins notes that giving £9 billion over 5 years means that “Microsoft gets one pound of every 13 spent” by the UK government on digital technology.

- Didn’t Take Long To Reveal The UK’s Online Safety Act Is Exactly The Privacy-Crushing Failure Everyone Warned About (TechDirt) — 5 of the top 10 apps in the Apple store are VPNs, and “Yes, you read that right. A law supposedly designed to protect children now requires victims of sexual assault to submit government IDs to access support communities.” Slow claps all round.

- In the Future All Food Will Be Cooked in a Microwave, and if You Can’t Deal With That Then You Need to Get Out of the Kitchen (Random Thoughts) — Colin Cornaby with an absolutely on-point parody of the AI bubble. “I saw online another restaurant owner suggested deploying one thousand microwaves for each chef. This sounds like a great idea.”

- The Sunday Morning Post: Why Exercise Is a Miracle Drug (Derek Thompson) — I can’t do proper cardio at the moment, but I’m trying to get a long walk in every day and, six days out of seven, I’m lifting weights. Exercise is important: “To a best approximation, aerobic fitness and weight-training seem to increase our metabolism, improve mitochondrial function, fortify our immune system, reduce inflammation, improve tissue-specific adaptations, and protect against disease.”

- Face it: you’re a crazy person (Experimental History) — I love the way that Adam Mastroianni writes, and this post is a great example of why. “There’s no amount of willpower that can carry you through a lifetime of Tuesday afternoons. Whatever you’re supposed to be doing in those hours, you’d better want to do it.”

- You can’t fight enshittification (Pluralistic) — A little bit pessimistic, but nevertheless true from Cory Doctorow: “Enshittification is not the result of people making bad choices: it’s the result of bad policies that produce bad systems… When all your friends are going to a festival, are you really going to opt out because the event requires you to use the Ticketmaster app (because Ticketmaster has a monopoly over event ticketing)? If so, you’re not gonna have a lot of friends, which is a pretty shitty way to live.”

- Do we need the wealthy? (Funding the Future) — Richard Taylor, Emeritus Professor of Accounting at the University of Sheffield’s Management School, with a well-argued video (with transcript) of why we shouldn’t be particularly bothered if rich people threaten to quit the UK due to a higher tax burden.

👋 Until next week!

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 3rd August 2025

Thought Shrapnel is in “low-power mode” over the summer, sharing 10 interesting things with minimal commentary ☀️

- The Planet Can’t Afford Billionaires (TIME) – “The scale of today’s social and environmental injustices cannot be fixed through minor tweaks to the existing financial system.”

- 2,500-year-old Siberian ‘ice mummy’ had intricate tattoos, imaging reveals (BBC News) – This is genuinely incredible, both in terms of the reconstruction and the talent of prehistoric tattoo artists.

- The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025 (The Week) — While we’re talking about history, did you know that the eruption of Mount Vesuvius 2,000 turned one mans brain into glass?

- Learning Is Slower Than You Think — And That’s the Point (The Intelligence Loop) – I love this line: “The struggle of learning doesn’t just shape the individual. It creates community.”

- I’m not ignoring your message – I’m overwhelmed by the tyranny of being reachable (The Guardian) – This article not only cites philosopher Byung-Chul Han, author of Psychopolitics but also uses the phrases “multiverse fatigue” and “attention residue.” Good stuff, especially the advice not to ghost people.

- Mistral’s new “environmental audit” shows how much AI is hurting the planet (Ara Technica) – As ever, it’s not the individual actions that are problematic, but when they are taken in aggregate. For me, it’s the lack of oversight and regulation of Big Tech in general that’s the issue.

- Brits can get around Discord’s age verification thanks to Death Stranding’s photo mode, bypassing the measure introduced with the UK’s Online Safety Act. We tried it and it works—thanks, Kojima (PC Gamer) – I mean, the story is in the lengthy title. I wouldn’t be surprised if MPs have shares in VPN companies.

- Do not download the app, use the website (Ibrahim Diallo) – As Cory Doctorow also points out in his excellent CBC podcast series Understood: Who Broke the Internet? apps are just for tracking and surveillance, not for your convenience.

- The Rise of Shippable Microfactories (Thesis Driven) – On-demand fabrication via temporary, on-site “microfactories” could be the future.

- Social media is dead – here’s what comes next (New Scientist) – It’s nice to see worker co-ops painted in such a positive light on this article.

👋 That’s it until next week!

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 27th July 2025

A reminder that Thought Shrapnel is in “low-power mode” over the summer. Here are 10 interesting things with minimal commentary ☀️

- The bewildering phenomenon of declining quality (EL PAÍS)— Wow, this is quite the article: “Put another way: it’s not the quality of things that’s declined — it’s us.”

- ‘I’d had 28 years of depression – now it was gone’: Comic Paul Foot on three seconds that changed his life (The Guardian) — The only thing I’ve felt similar was about 20 years ago which marked the start of the end of a period of stress and anxiety. My work environment was causing it, and my body suddenly said “no more.”

- What Happens When Housing Prices Go Down (because they are)? (Chuck with Strong Towns) — This article is US-focused, but house prices have started to fall in the UK, too. The property market isn’t designed for this to happen.

- What Scientists Learned Scanning the Bodies of 100,000 Brits (Bloomberg) — This is promising: an anonymised database of medical images which gives new insights into disease and helps to predict medical conditions. The process is entirely opt-in, unlike the grab of data by Palantir via the NHS federated data platform.

- Status, class, and the crisis of expertise (Conspicuous Cognition) — An eloquent explanation of what’s happened over the last 15-20 years: “[T]he populist celebration of “common sense” over expert authority… enacts an exhilarating status reversal. It frames ordinary people—those without educational credentials—as the real source of knowledge and wisdom. It creates the conditions for epistemic equality. It says that there is no need to accept assistance from fancy intellectuals with fancy degrees—and so no need to grant them status.”

- You can’t outrun a bad diet. Food — not lack of exercise — fuels obesity, study finds (NPR)— Since January, the amount of cardio I’ve been able to do has gone off a cliff. Weirdly, I’ve lost weight, which I guess that’s muscle loss, but I’ve also had to be really careful about what I’ve been eating.

- Cops say criminals use a Google Pixel with GrapheneOS — I say that’s freedom (Android Authority) — I use GrapheneOS, a security-hardened version of Android on my Pixel Fold. It’s great, and I’m always surprised at the experience others have when I see others using their phones. Apparently, using this OS means I’m bracketed with drug dealers. Ah well.

- How to increase your surface area for luck (Useful Fictions) — I’ve said for years that it’s possible to increase what I would call your serendipity surface. Here’s another author saying something similar.

- Surprising Science: How Electric Cars Quietly Transform Urban Air (Modern Engineering Marvels) — Last year, there was some kind of study which summised that because EVs are heavier, they must cause more microplastic pollution via tyres. More recent investgations show this isn’t true, and in fact they produce “38% less particulate pollution than gas-powered cars before even considering their lack of tailpipe emissions.”

- World’s top court says major polluters may need to pay reparations for climate harm (CNN Climate) — The President of the International Court of Justice, Yuji Iwasawa, has presented an advisory opinion running to 500 pages. He stated: “The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is essential for the enjoyment of other human rights… Failure of a state to take appropriate action to protect the climate system … may constitute an internationally wrongful act.” Hopefully this will lead to some action, but I’m not holding my breath.

👋 That’s it until next week! Check out my latest week note if you’re still looking for something to read.

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 20th July 2025

Thought Shrapnel continues in low-power mode over the summer: 10 interesting things each week with minimal commentary ☀️

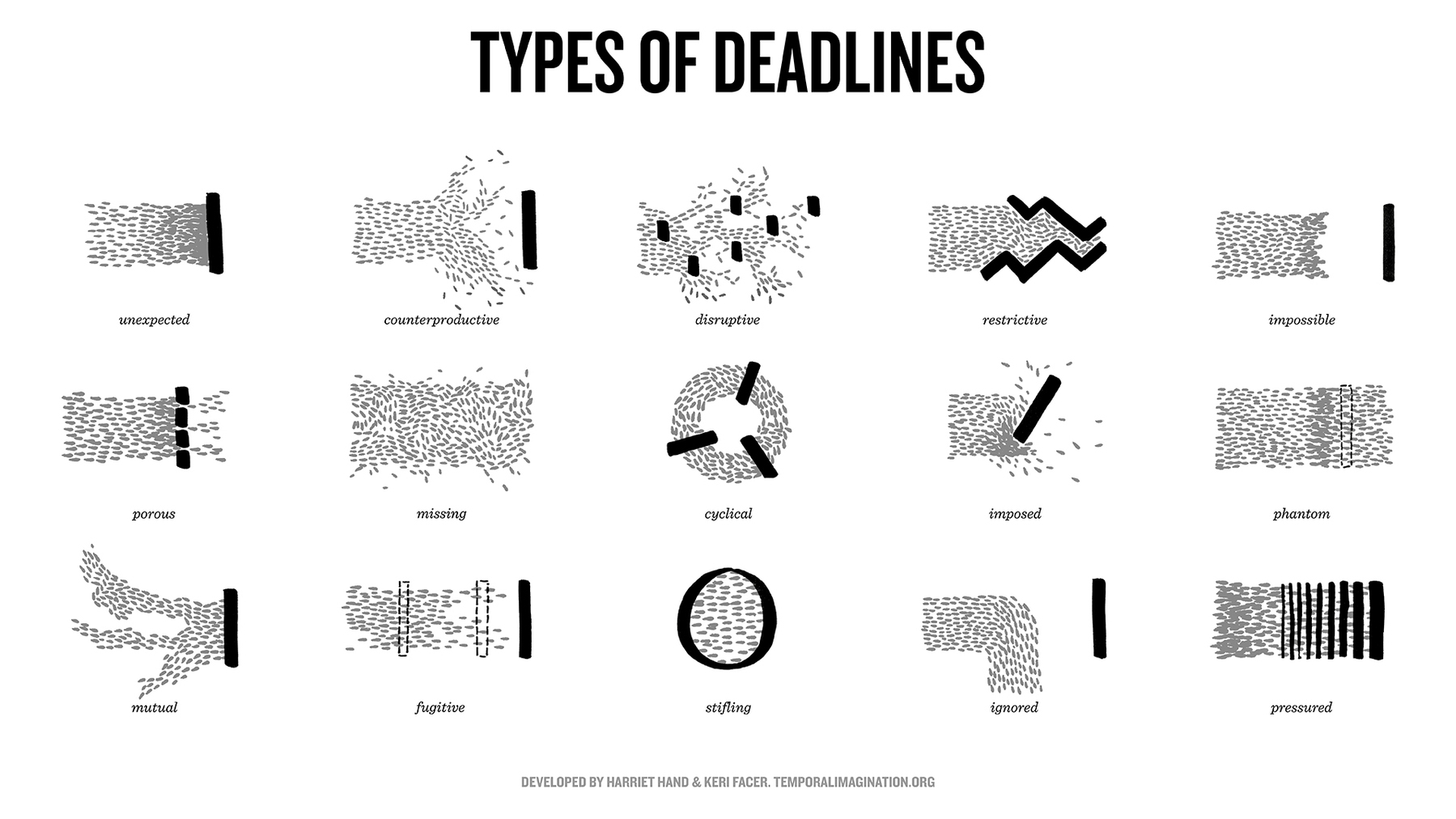

- Timelines, deadlines and lifelines (Temporal Imagination) — The above image, which I think is fantastic, comes from a workshop by Keri Facer and Harriet Hand and “explores some of the habits we have of thinking with time that are inherited and powerful.” You can purchase a limited-edition, hand-pressed portrait version of the above image at The Department of Small Works.

- Sixteen and 17-year-olds will be able to vote in next general election (Sky News) — It was in their manifesto, but you never know with this Labour government. It means my daughter, who will be 17 at the time of the next UK General Election, will be able to vote!

- Treating beef like coal would make a big dent in greenhouse-gas emissions (The Economist) — If you care about the climate emergency and want to do something about it, you should stop eating beef (and preferably all meat).

- The new solar: what colour panel would you like? (The Reengineer) — After having a heat pump installed last month, we’re getting (standard) solar panels in a few weeks' time. These coloured solar panels, though, look very cool and are likely to help with uptake.

- A first-party data reality check (OLDaily) — I agree with Stephen Downes' take on advertising here. I hate it, and believe its pervasiveness in society to be antithetical to human flourishing.

- How culture is made (Metalabel) - I love this from Yancey Strickler: “A metalabel is a release club where groups of people who share the same interests drop and support work that reflects their point of view.” I am absolutely up for this approach, especially after reading the Adam Curtis quote he cites.

- ‘The perfect accompaniment to life’: why is a 12th-century nun the hottest name in experimental music? (The Guardian) — I used an illustration by Hildegard of Bingen, 12th century nun, to illustrate a post about migraines last year. What I didn’t know was how influential her music was, and how much of her creative outpouring happened in her forties. Inspiring.

- There is No Meritocracy Without Lottocracy (Assemble America) — Given how much of life is down to serendipity and chance (including where and to whom you were born) I think we should lean into this a bit: “With random selection, no action or investment can meaningfully improve one’s chances, rendering efforts to manipulate the system worthless. This nullifies political capital and ensures that authority is not seized by those adept merely at influencing outcomes through charm, money, or connections.”

- How GLP-1s Are Breaking Life Insurance (GLP-1 Digest) — It looks like the class of drugs better known by brand names such as Ozempic and Mounjaro are likely to have the same kind of effect as statins on the general population.

- How much does your road weigh? (The Architectural Review) — “Today, there is an average of 37 tonnes of road per inhabitant of the planet. The weight of the road network alone accounts for a third of all construction worldwide, and has grown exponentially in the 20th century. There is 10 times more bitumen, in mass, than there are living animals. Yet growth in the mass of roads does not automatically correspond to population growth, or translate into increased length of road networks.” 🤯

👋 Until next week! I’m still around so feel free to comment / hit reply on this, and let me know what you enjoyed reading.

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 13th July 2025

A reminder that Thought Shrapnel is in low-power mode over the summer. I’m continuing share 10 things each week — but in a single post, with a tiny bit of commentary ☀️

- ZWO Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2025 shortlist (RMG) — The above image is entitled “Dragon Tree Trails” by Benjamin Barakat and it’s made up of 300 individual exposures. It’s one of a number of stunning issues on this shortlist.

- Artificial intelligence is the opposite of education (imperfect offerings) — Helen Beetham goes full hardcore mode against AI (by which I understand she means the sociotechnical system around generative AI). I hope she releases the podcast episode I recorded with her a few months ago soon!

- AI Can’t Take Over Soon Enough For Me. (Roving Dynamics Ltd) — Literally the opposite view to Helen, although not as eloquently stated. I’m somewhere in the middle of the two, ever since reading Fully Automated Luxury Communism.

- Jack Dorsey made an encrypted Bluetooth messaging app (The Verge) — In many ways, Bluetooth mesh messaging is nothing new (see Briar). However, bitchat adds end-to-end encryption, message encryption, battery optimisation, and other useful features. It’s already been ported to Android.

- 4.6 Billion Years On, the Sun Is Having a Moment (The New Yorker) — In a few weeks' time we’re getting as many solar panels installed Chez Belshaw as possible. This article explains why.

- The Mask-Off Moment for Digital Identity _(The New Design Congress) — This is the foreword to an upcoming report which sounds like it’s going to be dynamite. I work in the area of digital credentials, mainly to do with recognition but there is obviously quite a large digital identity component to all of that…

- Junior Roles Aren’t Going Away (In The AIrena) — I’d ordinarily have a lot to say about this but, largely, I agree with it. What you get out of generative AI is largely what you put into it. And that includes clarity of thought/intention.

- Stop making me log in to everything (Embedded) — I mean, the irony of having to login to read all of this article, but again I’ve thought a lot about this. Especially when AI companies are hoovering up the open web.

- You’re Not Wasting Time, You’re Wasting Your Life (Part 1) (Part 2) (The Daily Stoic) — Listen to both parts for context, as this conversation between Ryan Holiday and Rutger Bregman is fascinating. Part 2 is gold: Bregman talks about his book Moral Ambition and how the quotation attributed to Margaret Mead is absolutely true.

- No (Poetry Foundation) I’m not sure where I came across this article by Anne Boyer from 2017 but it is magnificent: “History is full of people who just didn’t. They said no thank you, turned away, ran away to the desert, stood on the streets in rags, lived in barrels, burned down their own houses, walked barefoot through town, killed their rapists, pushed away dinner, meditated into the light.”

👋 There we go! I’m still on the other end of the internet, so feel free to comment / hit reply on this, and let me know what resonated.

– Doug

💥 Thought Shrapnel: 6th July 2025

Thought Shrapnel is going into low-power mode for a few weeks over the summer. Instead of posting nothing at all, I’ve decided to continue to share 10 things each week — but in a single post, with minimal commentary ☀️

- Text therapy: study finds couples who use emojis in text messages feel closer (The Guardian) — Makes sense to me! I went to a presentation once that called emoji the most significant visual language since hieroglyphics.

- On July 7, Gemini AI will access your WhatsApp and more. Learn how to disable it on Android. (Tuta) — I use AI on a regular basis, but I don’t want Google’s generative AI playing fast-and-loose with all of my data, thank you very much.

- AI spots deadly heart risk most doctors can’t see (ScienceDaily) — It looks like a combination of AI and human oversight of things like scan results is likely to be game-changing.

- Flounder Mode (Colossus Review) — I love this piece on Kevin Kelly, especially the parts about “illegible career paths” and having a “good day, most days”. Refreshing.

- Changing Assessment: How to Design Curriculum for Human Flourishing (Conrad Hughes) — This 120-page, CC-licensed book looks great and exactly what we need to redesign assessment in the age of AI.

- Ghost and WordPress announce deeper social web collaboration (PPC Land) — Long-form content on the Fediverse is becoming more popular. See also this announcement from Bonfire.

- Writing Code Was Never The Bottleneck (ordep.dev) — This post is about code, but the same is true for anything: producing content isn’t the bottleneck, it’s the “clear thinking, careful review, and thoughtful design” that takes time.

- Millions of websites to get ‘game-changing’ AI bot blocker (BBC News) — There’s an element of closing door after the horse has bolted to this, but Cloudflare is a major player and their “Pay Per Crawl” system could change things.

- Project Vend: Can Claude run a small shop? (And why does that matter?) (Anthropic) — Laughable. Read in conjunction with this and this.

- Your Voice, Your World, Your Connections — The Reclaim Open 2025 conference happens online from 4-6 November, with submissions (in the form of a blog post) due by August 30th. (Side note: I always love see illustrations by Bryan Mathers on Reclaim sites, having introduced him to Jim Groom almost a decade ago around a table in Barcelona which also included Audrey Watters. Fun times.)

👋 That’s it! Have a good week. I’m still around if you comment / hit reply on this, so let me know what resonates.

– Doug