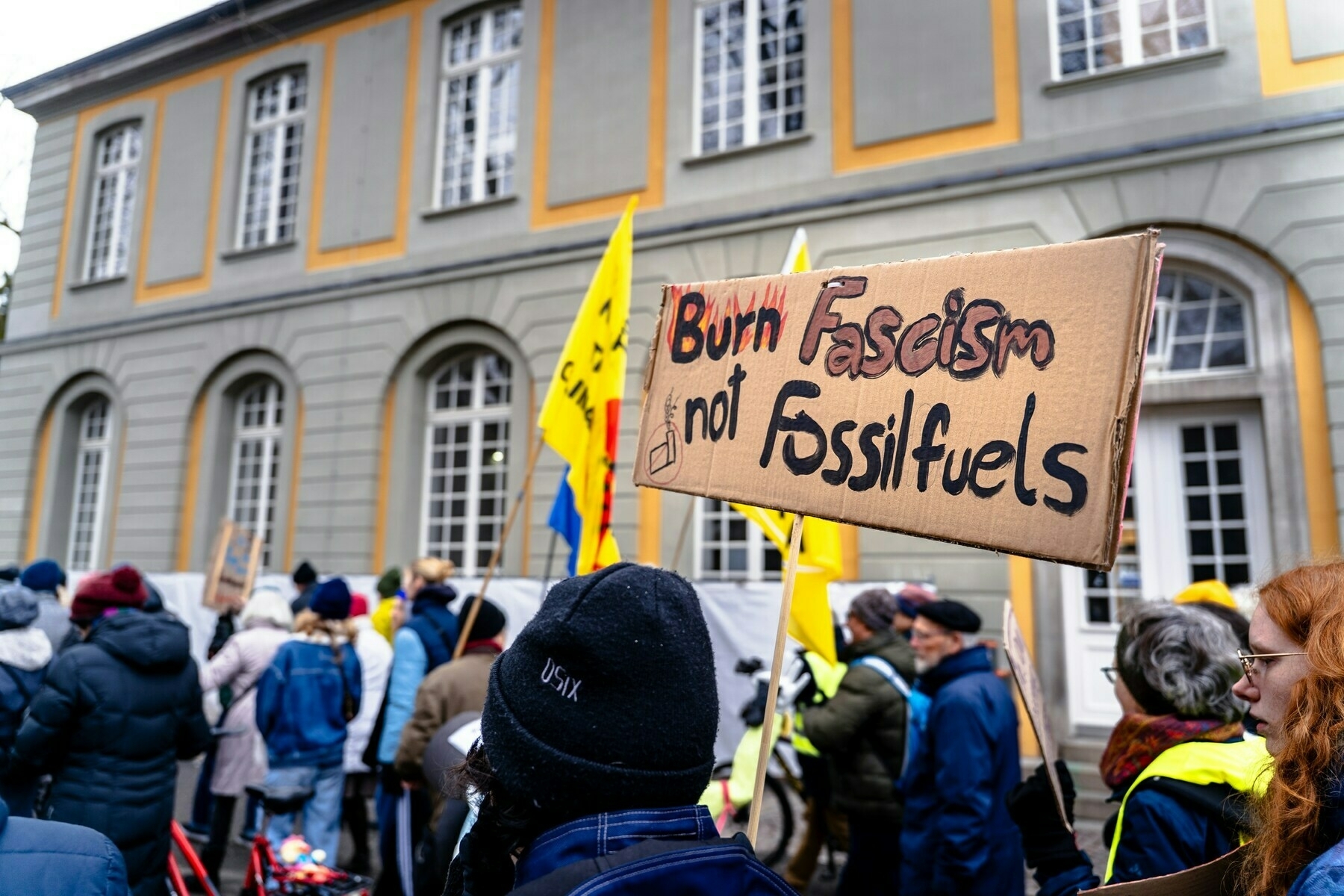

People think that fascism arrives in fancy dress

I said last week there are more historical authoritarian regimes to compare what’s happening around the world to than just Nazi Germany. I’m sick of my news feeds being full of people freaking out about what’s happening, as if this hasn’t been going on for years now.

I’m a reader of The Guardian and subscribe to the weekly print edition. But I’m finding the pointing-and-staring a little grating, which is why I appreciate this from Zoe Williams. I appreciate Carole Cadwalladr’s candid articles even more — although she does tend to post them on the Nazi-platforming Substack.

Like many people, I often feel as if I grew up with the Michael Rosen poem that starts: “I sometimes fear that / people think that fascism arrives in fancy dress.” In fact, it was written in 2014, but it was such a neat distillation that it instantly joined the canon of words that had always existed, right up there with clouds being lonely and parents fucking you up. Obviously, fascism arrives as your friend. How else would it arrive?

[…]

Between 1933 and 1939, the journalist Charlotte Beradt compiled The Third Reich of Dreams, in which she transcribed the nightmares of citizens from housemaids to small-business owners, then grouped them thematically, analysed them, and smuggled them to the US. They were published in 1968. A surprising, poignant number of them were about people dreaming that it was forbidden to dream, then freaking out in the dream because they knew they were illegitimately dreaming. There were amazingly prescient themes, of hyper-surveillance by the state before it had even begun, of barbarous violence, again, before it had started. But the paralysis theme was possibly the most recurrent and striking – people’s limbs frozen in Sieg Heils, voices frozen into silence, motifs of inaction from the most trivial to the most all-encompassing.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Mika Baumeister