- MIT Starts University Group to Build New Digital Credential System (EdSurge) — "The group... expects the standard to be “completely complementary” to the Open Badges standard that has been in the works for many years."

- European MOOC Consortium launches Common Micro-credential Framework (Education Technology) — "A leading driver for the development of the framework is the demand from learners to develop new knowledge, skills and competencies from shorter, recognised and quality-assured courses."

- Why a New Kind of ‘Badge’ Stands Out From the Crowd (The Chronicle of Higher Education) — "As we’ve been reporting, the buzz around certificates, badges, and other measures of achievement has been on the rise as employers have increasingly questioned whether a college degree is a reliable or adequate “signal” of an applicant’s capabilities."

Friday filchings

I'm having to write this ahead of time due to travel commitments. Still, there's the usual mixed bag of content in here, everything from digital credentials through to survival, with a bit of panpsychism thrown in for good measure.

Did any of these resonate with you? Let me know!

Competency Badges: the tail wagging the dog?

Recognition is from a certain point of view hyperlocal, and it is this hyperlocality that gives it its global value – not the other way around. The space of recognition is the community in which the competency is developed and activated. The recognition of a practitioner in a community is not reduced to those generally considered to belong to a “community of practice”, but to the intersection of multiple communities and practices, starting with the clients of these practices: the community of practice of chefs does not exist independently of the communities of their suppliers and clients. There is also a very strong link between individual recognition and that of the community to which the person is identified: shady notaries and politicians can bring discredit on an entire community.

Serge Ravet

As this roundup goes live I'll be at Open Belgium, and I'm looking forward to catching up with Serge while I'm there! My take on the points that he's making in this (long) post is actually what I'm talking about at the event: open initiatives need open organisations.

Universities do not exist ‘to produce students who are useful’, President says

Mr Higgins, who was opening a celebration of Trinity College Dublin’s College Historical Debating Society, said “universities are not there merely to produce students who are useful”.

“They are there to produce citizens who are respectful of the rights of others to participate and also to be able to participate fully, drawing on a wide range of scholarship,” he said on Monday night.

The President said there is a growing cohort of people who are alienated and “who feel they have lost their attachment to society and decision making”.

Jack Horgan-Jones (The Irish Times)

As a Philosophy graduate, I wholeheartedly agree with this, and also with his assessment of how people are obsessed with 'markets'.

Perennial philosophy

Not everyone will accept this sort of inclusivism. Some will insist on a stark choice between Jesus or hell, the Quran or hell. In some ways, overcertain exclusivism is a much better marketing strategy than sympathetic inclusivism. But if just some of the world’s population opened their minds to the wisdom of other religions, without having to leave their own faith, the world would be a better, more peaceful place. Like Aldous Huxley, I still believe in the possibility of growing spiritual convergence between different religions and philosophies, even if right now the tide seems to be going the other way.

Jules Evans (Aeon)

This is an interesting article about the philosophy of Aldous Huxley, whose books have always fascinated me. For some reason, I hadn't twigged that he was related to Thomas Henry Huxley (aka "Darwin's bulldog").

What the Death of iTunes Says About Our Digital Habits

So what really failed, maybe, wasn’t iTunes at all—it was the implicit promise of Gmail-style computing. The explosion of cloud storage and the invention of smartphones both arrived at roughly the same time, and they both subverted the idea that we should organize our computer. What they offered in its place was a vision of ease and readiness. What the idealized iPhone user and the idealized Gmail user shared was a perfect executive-functioning system: Every time they picked up their phone or opened their web browser, they knew exactly what they wanted to do, got it done with a calm single-mindedness, and then closed their device. This dream illuminated Inbox Zero and Kinfolk and minimalist writing apps. It didn’t work. What we got instead was Inbox Infinity and the algorithmic timeline. Each of us became a wanderer in a sea of content. Each of us adopted the tacit—but still shameful—assumption that we are just treading water, that the clock is always running, and that the work will never end.

Robinson Meyer (The Atlantic)

This is curiously-written (and well-written) piece, in the form of an ordered list, that takes you through the changes since iTunes launched. It's hard to disagree with the author's arguments.

Imagine a world without YouTube

But what if YouTube had failed? Would we have missed out on decades of cultural phenomena and innovative ideas? Would we have avoided a wave of dystopian propaganda and misinformation? Or would the internet have simply spiraled into new — yet strangely familiar — shapes, with their own joys and disasters?

Adi Robertson (The Verge)

I love this approach of imagining how the world would have been different had YouTube not been the massive success it's been over the last 15 years. Food for thought.

Big Tech Is Testing You

It’s tempting to look for laws of people the way we look for the laws of gravity. But science is hard, people are complex, and generalizing can be problematic. Although experiments might be the ultimate truthtellers, they can also lead us astray in surprising ways.

Hannah Fry (The New Yorker)

A balanced look at the way that companies, especially those we classify as 'Big Tech' tend to experiment for the purposes of engagement and, ultimately, profit. Definitely worth a read.

Trust people, not companies

The trend to tap into is the changing nature of trust. One of the biggest social trends of our time is the loss of faith in institutions and previously trusted authorities. People no longer trust the Government to tell them the truth. Banks are less trusted than ever since the Financial Crisis. The mainstream media can no longer be trusted by many. Fake news. The anti-vac movement. At the same time, we have a generation of people who are looking to their peers for information.

Lawrence Lundy (Outlier Ventures)

This post is making the case for blockchain-based technologies. But the wider point is a better one, that we should trust people rather than companies.

The Forest Spirits of Today Are Computers

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature. Agriculture de-wilded the meadows and the forests, so that even a seemingly pristine landscape can be a heavily processed environment. Manufactured products have become thoroughly mixed in with natural structures. Now, our machines are becoming so lifelike we can’t tell the difference. Each stage of technological development adds layers of abstraction between us and the physical world. Few people experience nature red in tooth and claw, or would want to. So, although the world of basic physics may always remain mindless, we do not live in that world. We live in the world of those abstractions.

George Musser (Nautilus)

This article, about artificial 'panpsychism' is really challenging to the reader's initial assumptions (well, mine at least) and really makes you think.

The man who refused to freeze to death

It would appear that our brains are much better at coping in the cold than dealing with being too hot. This is because our bodies’ survival strategies centre around keeping our vital organs running at the expense of less essential body parts. The most essential of all, of course, is our brain. By the time that Shatayeva and her fellow climbers were experiencing cognitive issues, they were probably already experiencing other organ failures elsewhere in their bodies.

William Park (BBC Future)

Not just one story in this article, but several with fascinating links and information.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Header image by Tim Mossholder.

There’s no perfection where there’s no selection

So said Baltasar Gracián. One of the reasons that e-portfolios never really took off was because there's so much to read. Can you imagine sifting through hundreds of job applications where each applicant had a fully-fledged e-portfolio, including video content?

That's why I've been so interested in Open Badges, and have written plenty on the subject over the last eight years. If you're new to the party, there are various terms such as 'microcredentials', 'digital badges', and 'digital credentials'. The difference is in the standard which was previously stewarded by Mozilla (including at my time there) and now by IMS Global Learning Consortium.

When I left Mozilla, I did a lot of work with City & Guilds, an awarding body that's well known for its vocational qualifications. They took a particular interest in Open Badges, for obvious reasons. In this article for FE News, Kirstie Donnelly (Managing Director of the City & Guilds Group) explains their huge potential:

The fact that you can actually stack these credentials, and they become portable, then you can publish them through online, through your LinkedIn. I just think it puts a very different dynamic into how the learner owns their experience, but at the same time the employers and the education system can still influence very much how those credentials are built and stacked.

Kirstie Donnelly

Like it or not, a lot of education is 'signalling' — i.e. providing an indicator that you can do a thing. The great thing about Open Badges is that you can make credentials much more granular and, crucially, include evidence of your ability to do the thing you claim to be able to do.

As Tyler Cowen picks up on for Marginal Revolution, without this granularity, there's a knock-on effect upon societal inequality. Privilege is perpetuated. He quotes a working paper by Gaurab Aryal, Manudeep Bhuller, and Fabian Lange who state:

The social and the private returns to education differ when education can increase productivity and also be used to signal productivity. We show how instrumental variables can be used to separately identify and estimate the social and private returns to education within the employer learning framework of Farber and Gibbons (1996) and Altonji and Pierret (2001). What an instrumental variable identifies depends crucially on whether the instrument is hidden from or observed by the employers. If the instrument is hidden, it identifies the private returns to education, but if the instrument is observed by employers, it identifies the social returns to education.

Aryal, Bhuller, and Lange

I take this to mean that, in a marketplace, the more the 'buyers' (i.e. employers) understand what's on offer, the more this changes the way that 'sellers' (i.e. potential employees) position themselves. Open Badges and other technologies can help with this.

Understandably, a lot is made of digital credentials for recruitment. Indeed, I've often argued that badges are important at times of transition — whether into a job, on the job, or onto your next job. But they are also important for reasons other than employment.

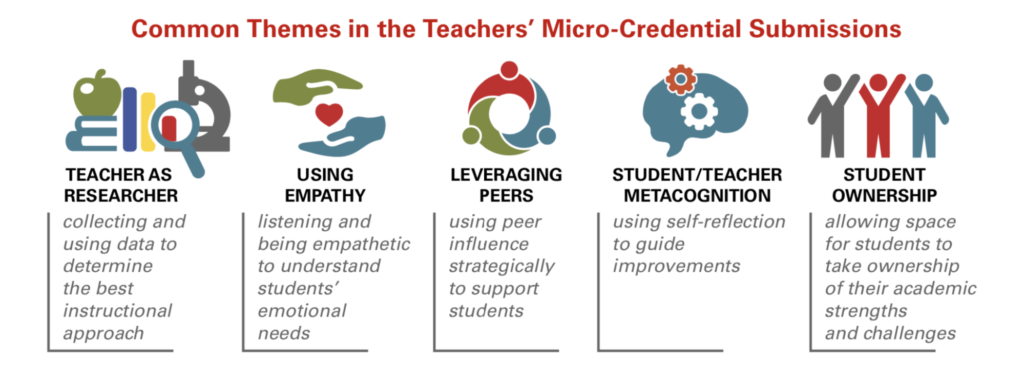

Lauren Acree, writing for Digital Promise explains how they can be used to foster more inclusive classrooms:

The Learner Variability micro-credentials ask educators to better understand students as learners. The micro-credentials support teachers as they partner with students in creating learning environments that address learners’ needs, leverage their strengths, and empower students to reflect and adjust as needed. We found that micro-credentials are one important way we can ultimately build teacher capacity to meet the needs of all learners.

Lauren Acree

The article includes this image representing a taxonomy of how teachers use micro-credentials in their work:

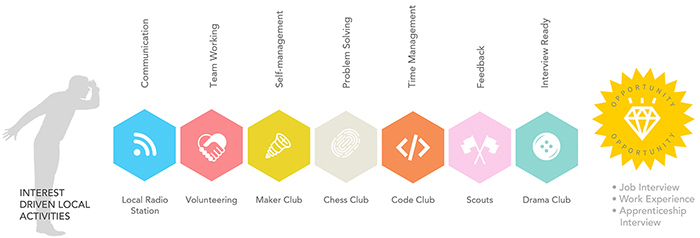

If we zoom out even further, we can see that micro-credentials as a form of 'currency' could play a big role in how we re-imagine society. Tim Riches, who I collaborated with while at both Mozilla and City & Guilds, has written a piece for the RSA about the 'Cities of Learning' projects that he's been involved in. All of these have used badges in some form or other.

In formal education, the value of learning is measured in qualifications. However, qualifications only capture a snapshot of what we know, not what we can do. What’s more, they tend to measure routine skills - the ones most vulnerable to automation and outsourcing.

[...]

Cities are full of people with unrecognised talents and potential. Cities are a huge untapped resource. Skills are developed every day in the community, at work and online, but they are hidden from view - disconnected from formal education and employers.

Tim Riches

I don't live in a city, and don't necessarily see them as the organising force here, but I do think that, on a societal level, there's something about recognising potential. Tim includes a graphic in his article which, I think, captures this nicely:

There's a phrase that's often used by feminist writers: "you can't be what you can't see". In other words, if you don't have any role models in a particular area, you're unlikely to think of exploring it. Similarly, if you don't know anyone who's a lawyer, or a sailor, or a horse rider, it's not perhaps something you'd think of doing.

If we can wrest control of innovations such as Open Badges away from the incumbents, and focus on human flourishing, I can see real opportunities for what Serge Ravet and others call 'open recognition'. Otherwise, we're just co-opting them to prop up and perpetuate the existing, unequal system.

Also check out:

Dis-trust and blockchain technologies

Serge Ravet is a deep thinker, a great guy, and a tireless advocate of Open Badges. In the first of a series of posts on his Learning Futures blog he explains why, in his opinion, blockchain-based credentials “are the wrong solution to a false problem”.

I wouldn’t phrase things with Serge’s colourful metaphors and language inspired by his native France, but I share many of his sentiments about the utility of blockchain-based technologies. Stephen Downes commented that he didn’t like the tone of the post, with “the metaphors and imagery seem[ing] more appropriate to a junior year fraternity chat room that to a discussion of blockchain and academics”.

It’s not my job as a commentator to be the tone police, but rather to gather up the nuggets and share them with you:

My attention was recently attracted to an article describing blockchains as “distributed trust” which they are not, but makes a nice and closer to the truth acronym: dis-trust…Blockchains are, in some circumstances, a great replacement for a centralised database. I find it difficult to get excited about that, as does Serge:

It is time for a copernican revolution, moving Blockchains from the centre of all designs to its periphery, as an accessory worth exploiting, or not. If there is a need for a database, the database doesn’t have to be distributed, if there are decisions to be made, they do not have to be left to an inflexible algorithm. On the other hand, if the design requires computer synchronisation, then blockchains might be one of the possible solutions, though not the only one.One of the difficulties, of course, is that hype perpetuates hype. If you're a vendor and your client (or potential client) asks you a question, you'd better be ready with a positive answer:

In the current strands for European funding, knowing that the European Union has decided to establish a “European blockchain infrastructure” in 2019, who will dare not to mention blockchains in their responses to the calls for tenders? And if you are a business and a client asks “when will you have a blockchain solution” what is the response most likely to get her attention: that’s not relevant to your problem or we have a blockchain solution that just matches your needs? How to resist the blockchain mania while providing clients and investors with something that sounds like what they want to hear?It's been four years since I first wrote about blockchain and badges. Since then, I co-founded a research project called BadgeChain, reflected on some of Serge's earlier work about a 'bit of trust', confirmed that BlockCerts and badges are friends, commented on why blockchain-based credentials are best used for high-stakes situations, written about blockchain and GDPR, called out blockchain as a futuristic integrity wand, agreed with Adam Greenfield that blockchain technologies are a stepping stone, reflected on the use of blockchain-based credentials in Higher Education, sighed about most examples of blockchain being bullshit, and explained that blockchain is about trust minimisation.

I think you can see where people like Serge and I stand on all this. It’s my considered opinion that blockchain would not have been seen as a ‘sexy’ technology if there wasn’t a huge cryptocurrency bubble attached to it.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: you need to understand a technology before you add it to the ‘essential’ box for any given project. There are high-stakes use cases for blockchain-based credentials, but they’re few and far between.

Source: Learning Futures

Image adapted from one in the Public Domain