- Tips for aspiring Mountain Leaders (@CraigTaylor74)

- Decentralised learning (@plaao)

- Slippers and sandals (@boyledsweetie)

- Carbon footprint of blockchain-based credentials (@ConcentricSky)

- How educators can promote their good practices without looking like they're bragging (@pullel)

- Why the last episode of Game of Thrones was so very bad (@MikeySwales)

- Be flexible with your planned route, especially in respect to the weather

- Don't buy super-expensive gear until you actually need it

- Write down your learning experiences the same day as you experience them

- Go walking with different people (although not with anyone who's got their ML, if you want it to count towards your QMDs!)

- Do buy walking poles and gaiters, even if you feel a prat using them

- Keep showing up in the same spaces every day/week so that people know where to find you (online/offline)

- Share your work without caring about recognition

- Point to other people and both recognise and celebrate their contributions

- MIT Starts University Group to Build New Digital Credential System (EdSurge) — "The group... expects the standard to be “completely complementary” to the Open Badges standard that has been in the works for many years."

- European MOOC Consortium launches Common Micro-credential Framework (Education Technology) — "A leading driver for the development of the framework is the demand from learners to develop new knowledge, skills and competencies from shorter, recognised and quality-assured courses."

- Why a New Kind of ‘Badge’ Stands Out From the Crowd (The Chronicle of Higher Education) — "As we’ve been reporting, the buzz around certificates, badges, and other measures of achievement has been on the rise as employers have increasingly questioned whether a college degree is a reliable or adequate “signal” of an applicant’s capabilities."

- ADCs (and their non-university equivalents) are already widely offered

- Traditional transcripts are not serving the workforce. The primary failure of traditional transcripts is that they do not connect verified competencies to jobs

- Accrediting agencies are beginning to focus on learning outcomes

- Young adults are demanding shorter and more workplace-relevant learning

- Open education demands ADCs

- Hiring practices increasingly depend on digital searches

- An ADC ecosystem is developing

- ADCs (and their non-university equivalents) are already widely offered

- Traditional transcripts are not serving the workforce. The primary failure of traditional transcripts is that they do not connect verified competencies to jobs

- Accrediting agencies are beginning to focus on learning outcomes

- Young adults are demanding shorter and more workplace-relevant learning

- Open education demands ADCs

- Hiring practices increasingly depend on digital searches

- An ADC ecosystem is developing

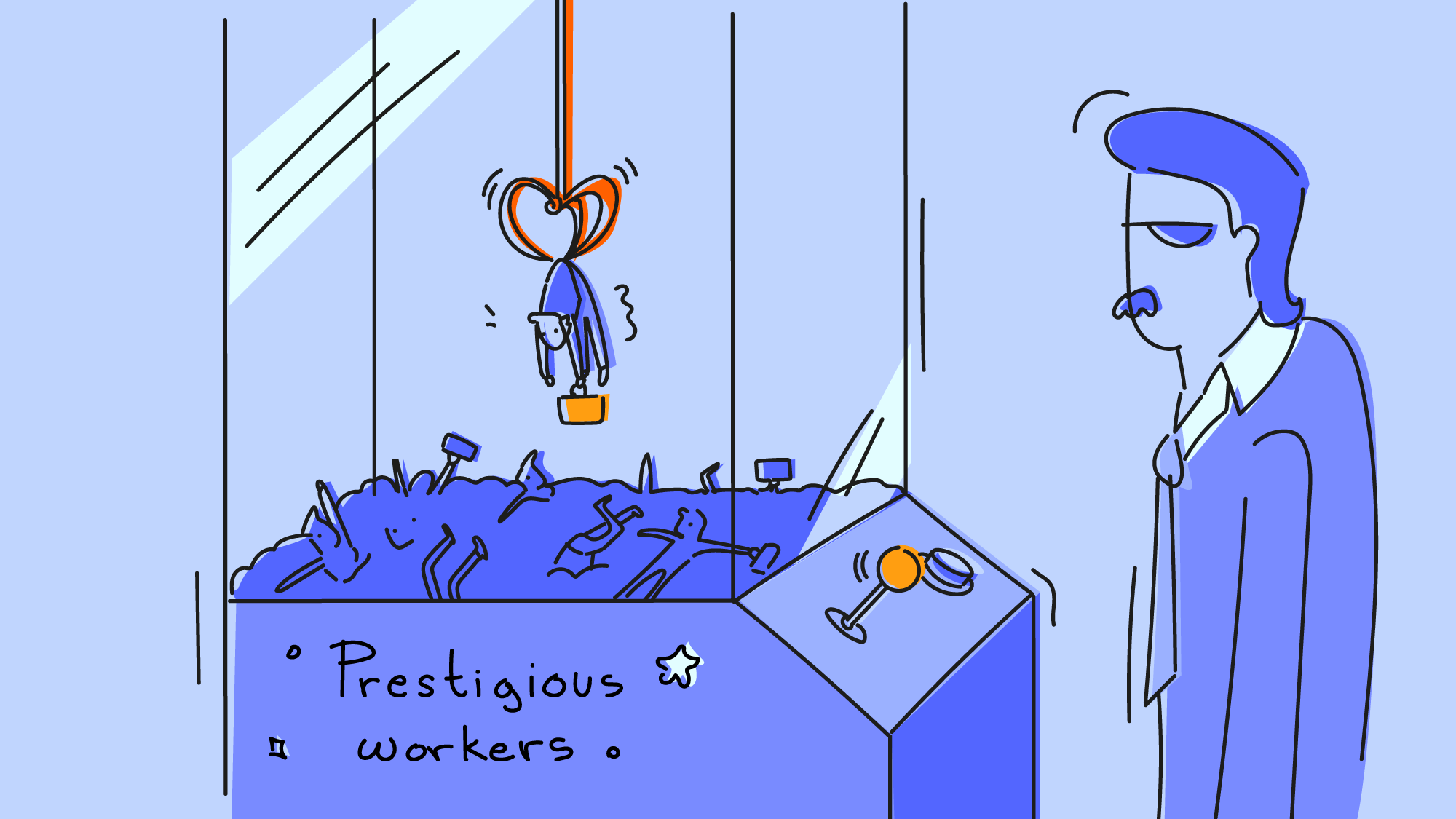

Prestige and associational value

This is 100% true and one of the reasons that I think that Open Badges and Verifiable Credentials are so awesome. Associational value is built-in for human beings, as we’re social creatures who set store by what other people value.

For example, I’m Dr. Belshaw which has a certain cachet and status in some circles. But people are usually much more interested/impressed by the fact that I worked for Mozilla and that one of our co-op’s clients is Greenpeace.

Them’s the breaks. And I feel like passing on this kind of wisdom to the younger generations is really important, to be honest, as a way that the world actually works.

A lot of people suspect that having-been part of a prestigious organisation (such a a famous university or an "elite" org in your field) gets you an unfair advantage when applying for future jobs.Source: Associational Value | Atoms vs BitsThere are two main avenues you could imagine for this advantage. One is basically nepotism: through the organisation you meet lots of other people who will later give you preferential access to jobs.

A second avenue is throughthe associtional value of the institution: that people with no specific connection to you or that organisation will see the name of Prestigious Institution on your resume and hire you because, well, you were at Prestigious Institution.

[…]

I think associational value often comes out of single-sentence descriptions of what somebody has done, and that therefore there are often relatively-easy ways to get 99% of the associational benefits of a prestigious institution at a much lower cost.

For example, in the magazine-writing world, people are often (approximately) defined by 1-3 of the most famous publications they’ve ever written for: “X’s work has appeared in TK, TK and TK,” or “this is my friend Y, she writes for [famous media brand].”

[…]

I’m not entirely sure how to work around this one, beyond the “try to get a mild affiliation with a prestigious institution, even if it’s an incredibly silly one” hack.

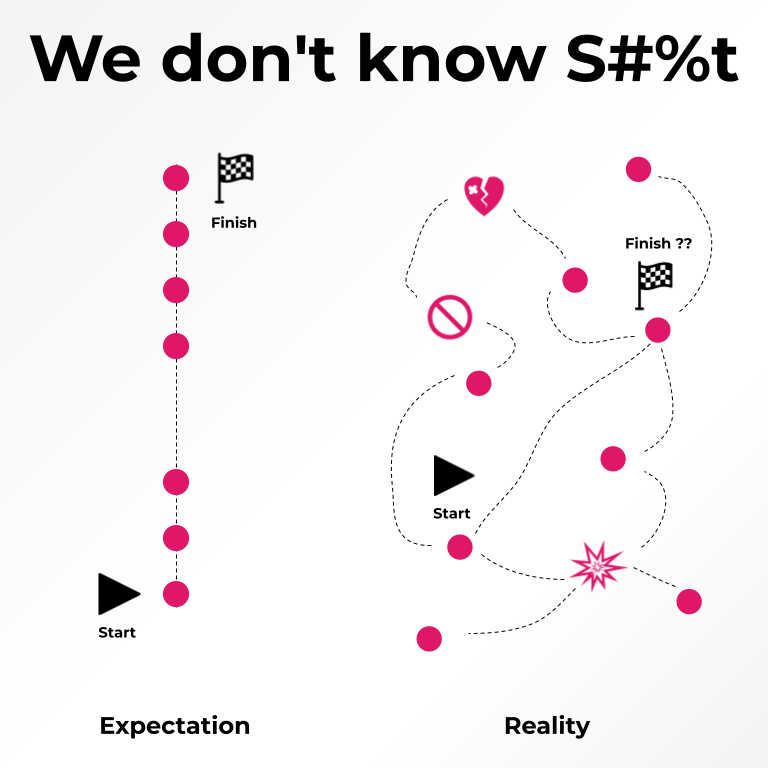

Learning through pathways

This is an interesting post that uses Google Maps as a metaphor for learning. In other words, get from where you are, to where you need to be, using an optimal route.

The author did some research, built pathways based on the findings, and presented them back to users. Who didn’t like them.

A similar approach was used in the Mozilla Discover project around Open Badges which is written up on Badge Wiki. The difference there, I guess, was that people were able to recognise specific inflection points that had meaning for them, and ascribe badges.

My opinion would be that people learn in different ways because of the context they bring to the table. You can rely on certain things to inspire most people, for example, or other things to resonate with some people. But there’s always a bit of experimentation to learning. It’s more like improvisational jazz than a symphony!

So, we do learn through pathways, but those pathways only have certain parts of the journey in common. To use another metaphor, it’s a bit like sharing a bus journey with other passengers for several stops, before getting on another bus (or hitch-hiking, or taking a taxi, or…)

I wanted to check the assumptions I had regarding the generation of paths for the Learning Map. So I scheduled interviews with instructors of these schools who were themselves also famous musicians. Their assumption was that I was interviewing them to create a story about their lives, but I was actually doing something far more interesting, I was deeply listening to the story of what and how they learned, and to the chronological order of their learning journey.More on this in this blog post about the session we ran at The Badge Summit on designing for recognition. Be sure to click through to the accompanying slide deck and the constellation model approach in slides 16 and 24!I asked them to describe their musical career, I let them know I wanted to create a timeline of their story, to start at the very beginning, and then to take me step by step through to their successes of today. Then I sat back and started to take notes:

Their first experience with music may have been with their mom who played the guitar, a lead singer they had a crush on, or a drum kit they got as a 5-year-old. They learned some key lessons and their journey kicked off. Over time, they may have learned to sing in Church, or worked in a recording studio. Some went to school, where they were introduced to new ideas from their peers, started a band, or trained underneath a mentor. Many went in completely different directions, they first become a chef, worked on a boat, or started bartending, each experience taught them skills they would later apply to their music. As they shared their experiences, I took notes, not about the events, the characters, or places, but only on the things they learned and when. I was mapping out their learning journeys, step by step, from their first experiences to their current work. I made an effort to cut through the superficial, and get to the heart of the lessons learned, this required the musician to deeply introspect, and was a fascinating experience on its own.

Several weeks later, after they had forgotten about the interviews and I had time to map each story out, I presented it back to them. But not as a story of their lives, instead, as a course, I wanted to run by them and get their professional opinion on. “What do you think of this course” “Do you think this is a good structure for a course?” I asked. They did not know this course was modeled after their own stories, they did not have any reason to tie this course back to the interviews conducted some months back and their responses were resounding: “This is a terribly designed course!” “How could you even think of wasting my time with this”, “Don’t you know that you need to understand X before you learn Y”…

Web3 and Ed3 are both problematic

Web3 is being discussed as if it’s anything other than the financialisation of everything. This post about ‘Ed3’ really struggles to square that circle when it comes to education. There are so many issues with it that I don’t really know where to start.

The bit that really jumped out for me, though, given that I’ve spent a decade working on Open Badges is the bit on credentialing. The cat is out of the bag by this point, especially in the “only paying for what you need” language. The whole point of education is that you don’t know what kind of person you’ll be at the end of it.

Anything else is just training.

Imagine if universities were fractionalized and you could earn the micro-credentials that mattered most for your career, only paid for what you needed, and owned a life-long portfolio with those credentials that were interoperable across all institutes & industries?Source: From Web3 to Ed3 - Reimagining Education in a Decentralized Worl… — MirrorWeb3 will also enable the metaverse to take shape over the next few decades; a universe of many buildable worlds that operate on decentralized infrastructure. The metaverse will make it possible to do everything we can do in the real world but enhanced by digital experiences & possible in an entirely virtual world.

What are microcredentials?

I suppose we should have listened when people told the team I was on at Mozilla time and time again that the name ‘Open Badges’ didn’t work for them. They didn’t seem to get the fact that they could call them anything they liked in their organisations; the important thing was that they aligned with the open standard.

A decade later, and ‘microcredentials’ seems to be one term that’s been adopted, especially towards the formal end of the credentialing spectrum. In this interview, Jackie Pichette, Director of Research and Policy for the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, takes a Higher Education-centric look at the landscape.

I may be cynical, but it comes across a lot like “that’s all very well in practice, but what about in theory?"

There’s a lot of confusion around the definition of the microcredential. When my colleagues and I started our research in February 2020, just before the world turned upside down, one of our aims was to help establish some common understanding. We engaged experts and consulted literature from around the world to help us answer questions like, What constitutes a microcredential? How is a microcredential different from a digital badge or a certificate?Source: How Do Microcredentials Stack Up? Part 1 | The EvoLLLutionWe landed on an umbrella definition of programs focused on a discrete set of competencies (i.e., skills, knowledge, attributes) that, by virtue of having a narrow focus, require less time to obtain than traditional credentials. We also came up with a typology to show the variation in this definition. For example, microcredentials can be self-paced to accommodate individual schedules, can follow a defined schedule or feature a mix of fixed- and self-paced elements.

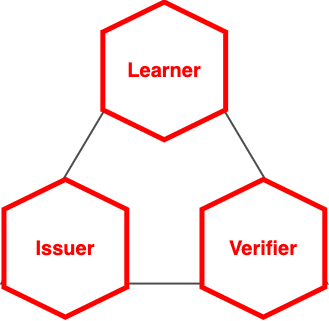

Open Badges Verifiable Credentials

I’m really grateful for people like Kerri Lemoie who understand digital credentials both technically and educationally, and have the time (she now works at Badgr) to steer this in the right direction.

Verifiable Credentials put learners in the center of a trust triangle with issuers and verifiers. They also add an additional layer of verification for the recipients. Open Badges can take advantage of this, be the first education-focused digital credential spec to promote personal protection of and access to data, and be part of the growing ecosystem that is exchanging Verifiable Credentials.Source: Open Badges as Verifiable Credentials | Kerri Lemoie

Badges everywhere!

As I predicted, 2021 is the year when Open Badges and digital credentials go mainstream. It’s unsurprising that ‘open’ isn’t front-and-centre in this Blackboard press release, but it’s still a win that this kind of thing is becoming normalised.

"We're excited to collaborate with Blackboard to integrate Badgr's stackable digital credentialing technology into Blackboard Learn," said Wayne Skipper, Founder of Concentric Sky. "Verifiable, skill-aligned micro-credentials are fast becoming the currency by which learners and employers improve the connections between learning outcomes and employment opportunities."Badgr Spaces, first available in Blackboard Learn, enables learners to earn personalized digital credentials and instructors to align course objectives and learning pathways with digital badges. Badgr Spaces empowers every member of a learning community with insight, direction and recognition on their personalized learning path.Source: Blackboard and Concentric Sky Partner to Make Badgr Micro-credentials and Stackable Pathways Available to More Learners

Gatekeepers of opportunity and the lottery of privilege

Despite starting out as a pejorative term, 'meritocracy' is something that, until recently, few people seem to have had a problem with. One of the best explanations of why meritocracy is a problematic idea is in this Mozilla article from a couple of years ago. Basically, it ascribes agency to those who were given opportunities due to pre-existing privilege.

In an interview with The Chronicle of Higher Education, Michael Sandel makes some very good points about the American university system, which can be more broadly applied to other western nations, such as the UK, which have elite universities.

The meritocratic hubris of elites is the conviction by those who land on top that their success is their own doing, that they have risen through a fair competition, that they therefore deserve the material benefits that the market showers upon their talents. Meritocratic hubris is the tendency of the successful to inhale too deeply of their success, to forget the luck and good fortune that helped them on their way. It goes along with the tendency to look down on those less fortunate, and less credentialed, than themselves. That gives rise to the sense of humiliation and resentment of those who are left out.

Michael Sandel, quoted in 'The Insufferable Hubris of the Well-Credentialed'

As someone who is reasonably well-credentialed, I nevertheless see a fundamental problem with requiring a degree as an 'entry-level' qualification. That's why I first got interested in Open Badges nearly a decade ago.

Despite the best efforts of the community, elite universities have a vested in maintaining the status quo. Eventually, the whole edifice will come crashing down, but right now, those universities are the gatekeepers to opportunity.

Society as a whole has made a four-year university degree a necessary condition for dignified work and a decent life. This is a mistake. Those of us in higher education can easily forget that most Americans do not have a four-year college degree. Nearly two-thirds do not.

[...]

We also need to reconsider the steep hierarchy of prestige that we have created between four-year colleges and universities, especially brand-name ones, and other institutions of learning. This hierarchy of prestige both reflects and exacerbates the tendency at the top to denigrate or depreciate the contributions to the economy made by people whose work does not depend on having a university diploma.

So the role that universities have been assigned, sitting astride the gateway of opportunity and success, is not good for those who have been left behind. But I’m not sure it’s good for elite universities themselves, either.

MICHAEL SANDEL, QUOTED IN 'THE INSUFFERABLE HUBRIS OF THE WELL-CREDENTIALED'

Thankfully, Sandel, has a rather delicious solution to decouple privilege from admission to elite universities. It's not a panacea, but I like it a first step.

What might we do about it? I make a proposal in the book that may get me in a lot of trouble in my neighborhood. Part of the problem is that having survived this high-pressured meritocratic gauntlet, it’s almost impossible for the students who win admission not to believe that they achieved their admission as a result of their own strenuous efforts. One can hardly blame them. So I think we should gently invite students to challenge this idea. I propose that colleges and universities that have far more applicants than they have places should consider what I call a “lottery of the qualified.” Over 40,000 students apply to Stanford and to Harvard for about 2,000 places. The admissions officers tell us that the majority are well-qualified. Among those, fill the first-year class through a lottery. My hunch is that the quality of discussion in our classes would in no way be impaired.

The main reason for doing this is to emphasize to students and their parents the role of luck in admission, and more broadly in success. It’s not introducing luck where it doesn’t already exist. To the contrary, there’s an enormous amount of luck in the present system. The lottery would highlight what is already the case.

MICHAEL SANDEL, QUOTED IN 'THE INSUFFERABLE HUBRIS OF THE WELL-CREDENTIALED'

Would people like me be worse off in a more egalitarian system? Probably. But that's kind of the point.

Friday filchings

I'm having to write this ahead of time due to travel commitments. Still, there's the usual mixed bag of content in here, everything from digital credentials through to survival, with a bit of panpsychism thrown in for good measure.

Did any of these resonate with you? Let me know!

Competency Badges: the tail wagging the dog?

Recognition is from a certain point of view hyperlocal, and it is this hyperlocality that gives it its global value – not the other way around. The space of recognition is the community in which the competency is developed and activated. The recognition of a practitioner in a community is not reduced to those generally considered to belong to a “community of practice”, but to the intersection of multiple communities and practices, starting with the clients of these practices: the community of practice of chefs does not exist independently of the communities of their suppliers and clients. There is also a very strong link between individual recognition and that of the community to which the person is identified: shady notaries and politicians can bring discredit on an entire community.

Serge Ravet

As this roundup goes live I'll be at Open Belgium, and I'm looking forward to catching up with Serge while I'm there! My take on the points that he's making in this (long) post is actually what I'm talking about at the event: open initiatives need open organisations.

Universities do not exist ‘to produce students who are useful’, President says

Mr Higgins, who was opening a celebration of Trinity College Dublin’s College Historical Debating Society, said “universities are not there merely to produce students who are useful”.

“They are there to produce citizens who are respectful of the rights of others to participate and also to be able to participate fully, drawing on a wide range of scholarship,” he said on Monday night.

The President said there is a growing cohort of people who are alienated and “who feel they have lost their attachment to society and decision making”.

Jack Horgan-Jones (The Irish Times)

As a Philosophy graduate, I wholeheartedly agree with this, and also with his assessment of how people are obsessed with 'markets'.

Perennial philosophy

Not everyone will accept this sort of inclusivism. Some will insist on a stark choice between Jesus or hell, the Quran or hell. In some ways, overcertain exclusivism is a much better marketing strategy than sympathetic inclusivism. But if just some of the world’s population opened their minds to the wisdom of other religions, without having to leave their own faith, the world would be a better, more peaceful place. Like Aldous Huxley, I still believe in the possibility of growing spiritual convergence between different religions and philosophies, even if right now the tide seems to be going the other way.

Jules Evans (Aeon)

This is an interesting article about the philosophy of Aldous Huxley, whose books have always fascinated me. For some reason, I hadn't twigged that he was related to Thomas Henry Huxley (aka "Darwin's bulldog").

What the Death of iTunes Says About Our Digital Habits

So what really failed, maybe, wasn’t iTunes at all—it was the implicit promise of Gmail-style computing. The explosion of cloud storage and the invention of smartphones both arrived at roughly the same time, and they both subverted the idea that we should organize our computer. What they offered in its place was a vision of ease and readiness. What the idealized iPhone user and the idealized Gmail user shared was a perfect executive-functioning system: Every time they picked up their phone or opened their web browser, they knew exactly what they wanted to do, got it done with a calm single-mindedness, and then closed their device. This dream illuminated Inbox Zero and Kinfolk and minimalist writing apps. It didn’t work. What we got instead was Inbox Infinity and the algorithmic timeline. Each of us became a wanderer in a sea of content. Each of us adopted the tacit—but still shameful—assumption that we are just treading water, that the clock is always running, and that the work will never end.

Robinson Meyer (The Atlantic)

This is curiously-written (and well-written) piece, in the form of an ordered list, that takes you through the changes since iTunes launched. It's hard to disagree with the author's arguments.

Imagine a world without YouTube

But what if YouTube had failed? Would we have missed out on decades of cultural phenomena and innovative ideas? Would we have avoided a wave of dystopian propaganda and misinformation? Or would the internet have simply spiraled into new — yet strangely familiar — shapes, with their own joys and disasters?

Adi Robertson (The Verge)

I love this approach of imagining how the world would have been different had YouTube not been the massive success it's been over the last 15 years. Food for thought.

Big Tech Is Testing You

It’s tempting to look for laws of people the way we look for the laws of gravity. But science is hard, people are complex, and generalizing can be problematic. Although experiments might be the ultimate truthtellers, they can also lead us astray in surprising ways.

Hannah Fry (The New Yorker)

A balanced look at the way that companies, especially those we classify as 'Big Tech' tend to experiment for the purposes of engagement and, ultimately, profit. Definitely worth a read.

Trust people, not companies

The trend to tap into is the changing nature of trust. One of the biggest social trends of our time is the loss of faith in institutions and previously trusted authorities. People no longer trust the Government to tell them the truth. Banks are less trusted than ever since the Financial Crisis. The mainstream media can no longer be trusted by many. Fake news. The anti-vac movement. At the same time, we have a generation of people who are looking to their peers for information.

Lawrence Lundy (Outlier Ventures)

This post is making the case for blockchain-based technologies. But the wider point is a better one, that we should trust people rather than companies.

The Forest Spirits of Today Are Computers

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature. Agriculture de-wilded the meadows and the forests, so that even a seemingly pristine landscape can be a heavily processed environment. Manufactured products have become thoroughly mixed in with natural structures. Now, our machines are becoming so lifelike we can’t tell the difference. Each stage of technological development adds layers of abstraction between us and the physical world. Few people experience nature red in tooth and claw, or would want to. So, although the world of basic physics may always remain mindless, we do not live in that world. We live in the world of those abstractions.

George Musser (Nautilus)

This article, about artificial 'panpsychism' is really challenging to the reader's initial assumptions (well, mine at least) and really makes you think.

The man who refused to freeze to death

It would appear that our brains are much better at coping in the cold than dealing with being too hot. This is because our bodies’ survival strategies centre around keeping our vital organs running at the expense of less essential body parts. The most essential of all, of course, is our brain. By the time that Shatayeva and her fellow climbers were experiencing cognitive issues, they were probably already experiencing other organ failures elsewhere in their bodies.

William Park (BBC Future)

Not just one story in this article, but several with fascinating links and information.

Enjoy this? Sign up for the weekly roundup and/or become a supporter!

Header image by Tim Mossholder.

The world is all variation and dissimilarity

Another quotation-as-title from Michel de Montaigne. I'm using it today, as I want to write a composite post based on a tweet I put out yesterday where I simply asked What shall I write about?

Note: today's update is a little different as it's immediately available on the open web, instead of being limited to supporters for seven days. It's an experiment!

Here's some responses I got to my question:

Never let it be said that I don't give the people what they want! Five short sections, based on the serious (and not-so-serious) answers I go from my Twitter followers.

1. Tips for aspiring Mountain Leaders

Well, I'm not even on the course yet (two more Quality Mountain Days to go!) but some tips I'd pass on are:

...and, of course, subscribe to The Bushcraft Padawan!

2. Decentralised learning

Decentralisation is an interesting concept, mainly because it's such an abstract concept for people to grasp. Usually, when people talk about decentralisation, they're either talking about politics or technology. Both, ultimately, are to do with power.

When it comes to learning, therefore, decentralised learning is all about empowering learners, which is often precisely the opposite of what we do in schools. We centralise instruction, and subject young people (and their teachers) to bells that control their time.

To my mind, decentralised learning is any attempt to empower learners to be more independent. That might involve them co-creating the curriculum, it might have something to do with the way we credential and/or recognise their learning. The important thing is that learning isn't something that's done to them.

3. Slippers and sandals

I'm wearing slippers right now, as I do when I'm in the house or working in my home office. I don't think you can go past Totes Isotoner, to be honest. Comfy!

Given I live in the North East of England, my opportunities to wear sandals are restricted to holidays and a few days in summer. I had a fantastic pair of Timberland sandals back in the day, but my wife finally threw them away because they were too smelly. I'm making do now with some other ones I found in the sale on Amazon, but they're actually slightly too big for me, which is annoying.

4. Carbon footprint of blockchain-based credentials

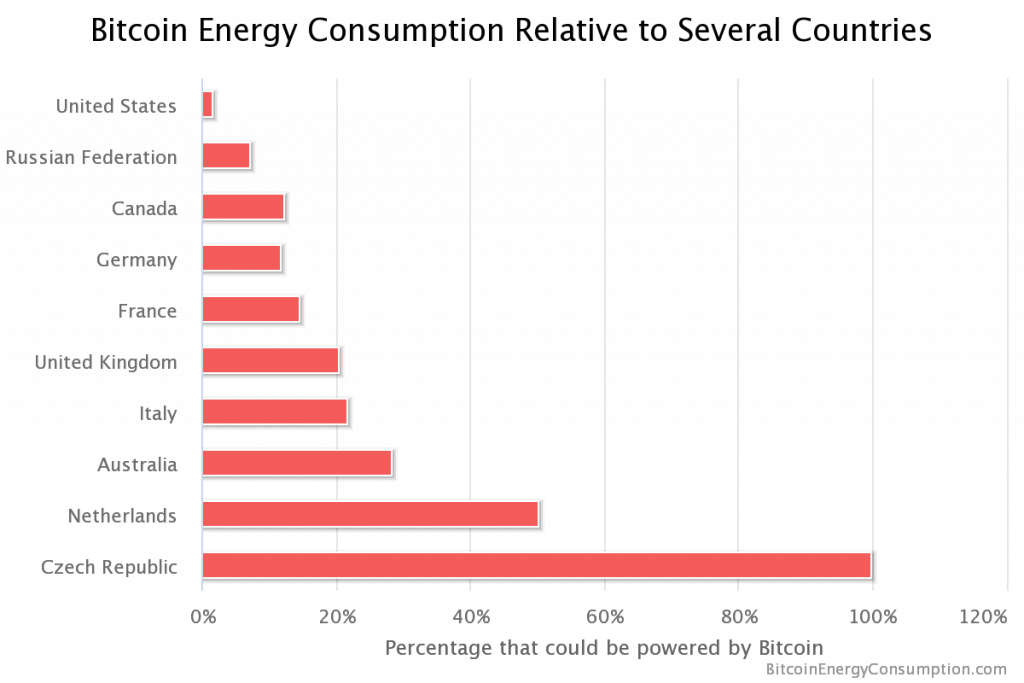

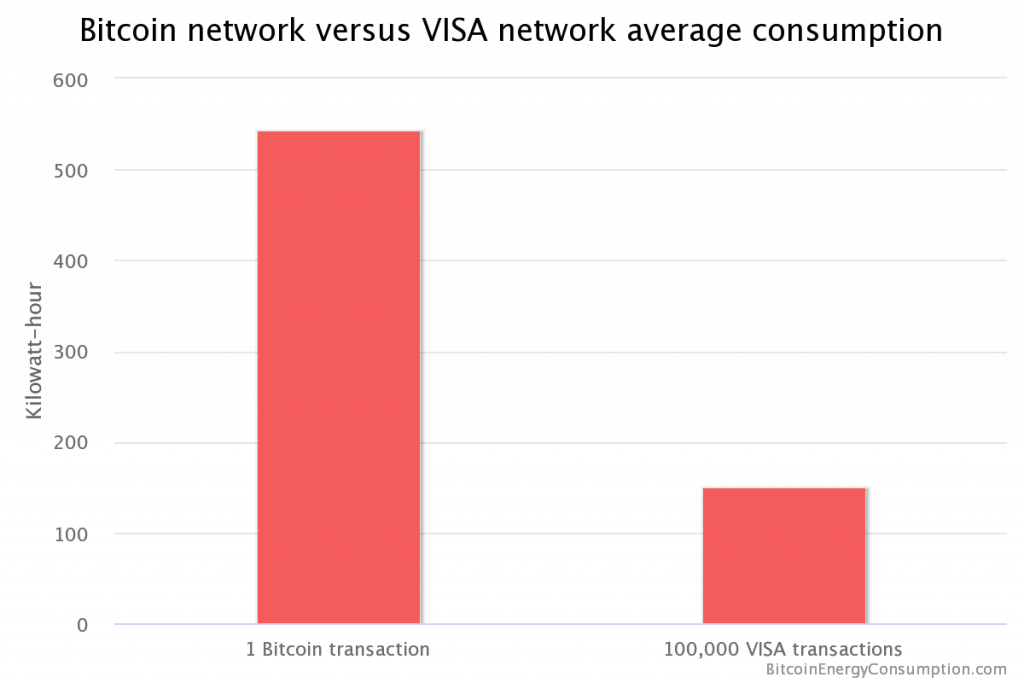

I'll start with the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, which gives us a couple of great charts to show the scale of the problem of using blockchains based on a proof-of-work algorithm:

That's right, the whole of the Czech Republic could be powered by the amount of energy required to run the Bitcoin network.

As you can see from the second chart, Bitcoin is a massive waste of energy versus our existing methods of payment. But what about other blockchain-based technologies, like Ethereum?

They've had the same problem, until recently, as Peter Fairley explains for IEEE Spectrum:

Like most cryptocurrencies, Ethereum relies on a computational competition called proof of work (PoW) . In PoW, all participants race to cryptographically secure transactions and add them to the blockchain’s globally distributed ledger. It’s a winner-takes-all contest, rewarded with newly minted cryptocoins. So the more computational firepower you have, the better your chances to profit.

[...]

Ethereum’s plan is to replace PoW with proof of stake (PoS)—an alternative mechanism for distributed consensus that was first applied to a cryptocurrency with the launch of Peercoin in 2012. Instead of millions of processors simultaneously processing the same transactions, PoS randomly picks one to do the job.

In PoS, the participants are called validators instead of miners, and the key is keeping them honest. PoS does this by requiring each validator to put up a stake—a pile of ether in Ethereum’s case—as collateral. A bigger stake earns a validator proportionately more chances at a turn, but it also means that a validator caught cheating has lots to lose.

Peter Fairley

Which brings us back to credentials. As I've said many times before, if you trust online banking and online shopping, then the Open Badges standard is secure enough for you. However, I can still see a use case for blockchain-based credentials, and wouldn't necessarily rule them out — especially if they're based on a PoS approach.

5. How educators can promote their good practices without looking like they're bragging

This is really contextual. What counts as 'bragging' in one culture and within one community won't be counted as such in another. It also depends on personality too, I guess — something we don't really talk about as educators (other than through the lens of 'character').

The only advice I can give is to do these three things:

Remember, the point is to make the world a better place, not to care who gets credit for making it better!

6. Why the last episode of Game of Thrones was so very bad

I've never even seen part of one episode, so perhaps this can help?

Do you have any questions for me to answer next time I do this?

There’s no perfection where there’s no selection

So said Baltasar Gracián. One of the reasons that e-portfolios never really took off was because there's so much to read. Can you imagine sifting through hundreds of job applications where each applicant had a fully-fledged e-portfolio, including video content?

That's why I've been so interested in Open Badges, and have written plenty on the subject over the last eight years. If you're new to the party, there are various terms such as 'microcredentials', 'digital badges', and 'digital credentials'. The difference is in the standard which was previously stewarded by Mozilla (including at my time there) and now by IMS Global Learning Consortium.

When I left Mozilla, I did a lot of work with City & Guilds, an awarding body that's well known for its vocational qualifications. They took a particular interest in Open Badges, for obvious reasons. In this article for FE News, Kirstie Donnelly (Managing Director of the City & Guilds Group) explains their huge potential:

The fact that you can actually stack these credentials, and they become portable, then you can publish them through online, through your LinkedIn. I just think it puts a very different dynamic into how the learner owns their experience, but at the same time the employers and the education system can still influence very much how those credentials are built and stacked.

Kirstie Donnelly

Like it or not, a lot of education is 'signalling' — i.e. providing an indicator that you can do a thing. The great thing about Open Badges is that you can make credentials much more granular and, crucially, include evidence of your ability to do the thing you claim to be able to do.

As Tyler Cowen picks up on for Marginal Revolution, without this granularity, there's a knock-on effect upon societal inequality. Privilege is perpetuated. He quotes a working paper by Gaurab Aryal, Manudeep Bhuller, and Fabian Lange who state:

The social and the private returns to education differ when education can increase productivity and also be used to signal productivity. We show how instrumental variables can be used to separately identify and estimate the social and private returns to education within the employer learning framework of Farber and Gibbons (1996) and Altonji and Pierret (2001). What an instrumental variable identifies depends crucially on whether the instrument is hidden from or observed by the employers. If the instrument is hidden, it identifies the private returns to education, but if the instrument is observed by employers, it identifies the social returns to education.

Aryal, Bhuller, and Lange

I take this to mean that, in a marketplace, the more the 'buyers' (i.e. employers) understand what's on offer, the more this changes the way that 'sellers' (i.e. potential employees) position themselves. Open Badges and other technologies can help with this.

Understandably, a lot is made of digital credentials for recruitment. Indeed, I've often argued that badges are important at times of transition — whether into a job, on the job, or onto your next job. But they are also important for reasons other than employment.

Lauren Acree, writing for Digital Promise explains how they can be used to foster more inclusive classrooms:

The Learner Variability micro-credentials ask educators to better understand students as learners. The micro-credentials support teachers as they partner with students in creating learning environments that address learners’ needs, leverage their strengths, and empower students to reflect and adjust as needed. We found that micro-credentials are one important way we can ultimately build teacher capacity to meet the needs of all learners.

Lauren Acree

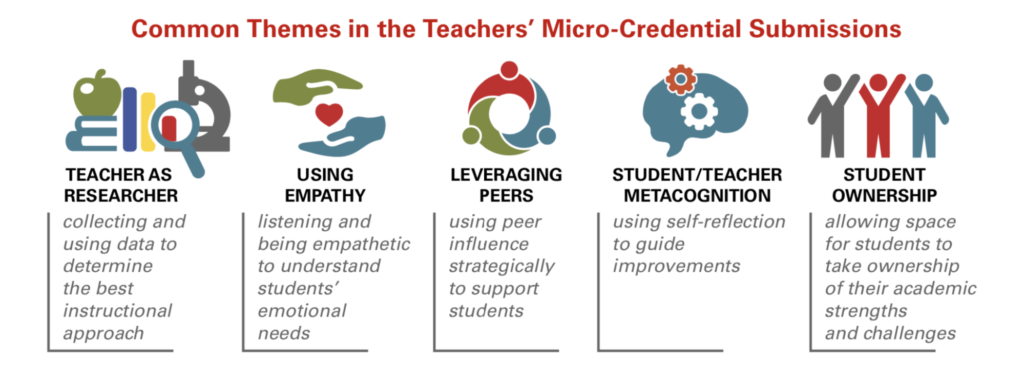

The article includes this image representing a taxonomy of how teachers use micro-credentials in their work:

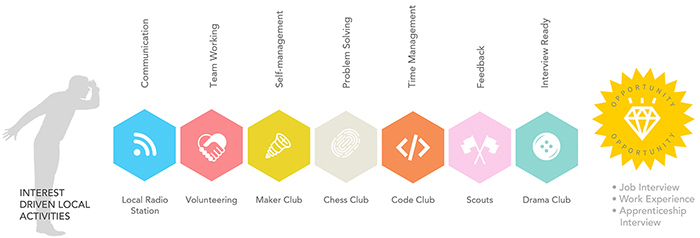

If we zoom out even further, we can see that micro-credentials as a form of 'currency' could play a big role in how we re-imagine society. Tim Riches, who I collaborated with while at both Mozilla and City & Guilds, has written a piece for the RSA about the 'Cities of Learning' projects that he's been involved in. All of these have used badges in some form or other.

In formal education, the value of learning is measured in qualifications. However, qualifications only capture a snapshot of what we know, not what we can do. What’s more, they tend to measure routine skills - the ones most vulnerable to automation and outsourcing.

[...]

Cities are full of people with unrecognised talents and potential. Cities are a huge untapped resource. Skills are developed every day in the community, at work and online, but they are hidden from view - disconnected from formal education and employers.

Tim Riches

I don't live in a city, and don't necessarily see them as the organising force here, but I do think that, on a societal level, there's something about recognising potential. Tim includes a graphic in his article which, I think, captures this nicely:

There's a phrase that's often used by feminist writers: "you can't be what you can't see". In other words, if you don't have any role models in a particular area, you're unlikely to think of exploring it. Similarly, if you don't know anyone who's a lawyer, or a sailor, or a horse rider, it's not perhaps something you'd think of doing.

If we can wrest control of innovations such as Open Badges away from the incumbents, and focus on human flourishing, I can see real opportunities for what Serge Ravet and others call 'open recognition'. Otherwise, we're just co-opting them to prop up and perpetuate the existing, unequal system.

Also check out:

Open Badges and ADCs

As someone who’s been involved with Open Badges since 2012, I’m always interested in the ebbs and flows of the language around their promotion and use.

This article in an article on EdScoop cites a Dean at UC Irvine, who talks about ‘Alternative Digital Credentials’:

Alternative digital credentials — virtual certificates for skill verification — are an institutional imperative, said Gary Matkin, dean of continuing education at the University of California, Irvine, who predicts they will become widely available in higher education within five years.Out of all of the people I’ve spoken to about Open Badges in the past seven years, universities are the ones who least like the term ‘badges’.“Like in the 90s when it was obvious that education was going to begin moving to an online format,” Matkin told EdScoop, “it is now the current progression that institutions will have to begin to issue ADCs.”

The article links to a report by the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) on ADCs which cites seven reasons that they’re an ‘institutional imperative’:

"Efforts to set universal technical and quality standards for badges and to establish comprehensive repositories for credentials conforming to a single standard will not succeed."You can't lump in quality standards with technical standards. The former is obviously doomed to fail, whereas the latter is somewhat inevitable.

Source: EdScoop

Open Badges and ADCs

As someone who’s been involved with Open Badges since 2012, I’m always interested in the ebbs and flows of the language around their promotion and use.

This article in an article on EdScoop cites a Dean at UC Irvine, who talks about ‘Alternative Digital Credentials’:

Alternative digital credentials — virtual certificates for skill verification — are an institutional imperative, said Gary Matkin, dean of continuing education at the University of California, Irvine, who predicts they will become widely available in higher education within five years.Out of all of the people I’ve spoken to about Open Badges in the past seven years, universities are the ones who least like the term ‘badges’.“Like in the 90s when it was obvious that education was going to begin moving to an online format,” Matkin told EdScoop, “it is now the current progression that institutions will have to begin to issue ADCs.”

The article links to a report by the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) on ADCs which cites seven reasons that they’re an ‘institutional imperative’:

"Efforts to set universal technical and quality standards for badges and to establish comprehensive repositories for credentials conforming to a single standard will not succeed."You can't lump in quality standards with technical standards. The former is obviously doomed to fail, whereas the latter is somewhat inevitable.

Source: EdScoop

Dis-trust and blockchain technologies

Serge Ravet is a deep thinker, a great guy, and a tireless advocate of Open Badges. In the first of a series of posts on his Learning Futures blog he explains why, in his opinion, blockchain-based credentials “are the wrong solution to a false problem”.

I wouldn’t phrase things with Serge’s colourful metaphors and language inspired by his native France, but I share many of his sentiments about the utility of blockchain-based technologies. Stephen Downes commented that he didn’t like the tone of the post, with “the metaphors and imagery seem[ing] more appropriate to a junior year fraternity chat room that to a discussion of blockchain and academics”.

It’s not my job as a commentator to be the tone police, but rather to gather up the nuggets and share them with you:

My attention was recently attracted to an article describing blockchains as “distributed trust” which they are not, but makes a nice and closer to the truth acronym: dis-trust…Blockchains are, in some circumstances, a great replacement for a centralised database. I find it difficult to get excited about that, as does Serge:

It is time for a copernican revolution, moving Blockchains from the centre of all designs to its periphery, as an accessory worth exploiting, or not. If there is a need for a database, the database doesn’t have to be distributed, if there are decisions to be made, they do not have to be left to an inflexible algorithm. On the other hand, if the design requires computer synchronisation, then blockchains might be one of the possible solutions, though not the only one.One of the difficulties, of course, is that hype perpetuates hype. If you're a vendor and your client (or potential client) asks you a question, you'd better be ready with a positive answer:

In the current strands for European funding, knowing that the European Union has decided to establish a “European blockchain infrastructure” in 2019, who will dare not to mention blockchains in their responses to the calls for tenders? And if you are a business and a client asks “when will you have a blockchain solution” what is the response most likely to get her attention: that’s not relevant to your problem or we have a blockchain solution that just matches your needs? How to resist the blockchain mania while providing clients and investors with something that sounds like what they want to hear?It's been four years since I first wrote about blockchain and badges. Since then, I co-founded a research project called BadgeChain, reflected on some of Serge's earlier work about a 'bit of trust', confirmed that BlockCerts and badges are friends, commented on why blockchain-based credentials are best used for high-stakes situations, written about blockchain and GDPR, called out blockchain as a futuristic integrity wand, agreed with Adam Greenfield that blockchain technologies are a stepping stone, reflected on the use of blockchain-based credentials in Higher Education, sighed about most examples of blockchain being bullshit, and explained that blockchain is about trust minimisation.

I think you can see where people like Serge and I stand on all this. It’s my considered opinion that blockchain would not have been seen as a ‘sexy’ technology if there wasn’t a huge cryptocurrency bubble attached to it.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: you need to understand a technology before you add it to the ‘essential’ box for any given project. There are high-stakes use cases for blockchain-based credentials, but they’re few and far between.

Source: Learning Futures

Image adapted from one in the Public Domain

Credentials and standardisation

Someone pinch me, because I must be dreaming. It’s 2018, right? So why are we still seeing this kind of article about Open Badges and digital credentials?

“We do have a little bit of a Wild West situation right now with alternative credentials,” said Alana Dunagan, a senior research fellow at the nonprofit Clayton Christensen Institute, which researches education innovation. The U.S. higher education system “doesn’t do a good job of separating the wheat from the chaff.”You'd think by now we'd realise that we have a huge opportunity to do something different here and not just replicate the existing system. Let's credential stuff that matters rather than some ridiculous notion of 'employability skills'. Open Badges and digital credentials shouldn't be just another stick to beat educational institutions.

Nor do they need to be ‘standardised’. Another person’s ‘wild west’ is another person’s landscape of huge opportunity. We not living in a world of 1950s career pathways.

“Everybody is scrambling to create microcredentials or badges,” Cheney said. “This has never been a precise marketplace, and we’re just speeding up that imprecision.”My eyes are rolling out of my head at this point. Thankfully, I’ve already written about misguided notions around ‘quality’ and ‘rigour’, as well thinking through in a bit more detail what earning a ‘credential’ actually means.Arizona State University, for example, is rapidly increasing the number of online courses in its continuing and professional education division, which confers both badges and certificates. According to staff, the division offers 200 courses and programs in a slew of categories, including art, history, education, health and law, and plans to provide more than 500 by next year.

Source: The Hechinger Report

Why badge endorsement is a game-changer

Since starting work with Moodle, I’ve been advocating for upgrading its Open Badges implementation to v2.0. It’s on the horizon, thankfully. The reason I’m particularly interested in this is endorsement, the value of which is explained in a post by Don Presant:

What’s so exciting about Endorsement, you may ask. Well, for one thing, it promises to resolve recurring questions about the “credibility of badges” by providing third party validation that can be formal (like accreditation) or informal (“fits our purpose”). Endorsement can also strengthen collaboration, increase portability and encourage the development of meaningful badge ecosystems.I've known Don for a number of years and have been consistently impressed by combination of idealism and pragmatism. He provides a version of Open Badge Factory in Canada called 'CanCred' and, under these auspices, is working on a project around a Humanitarian Passport.

Endorsement of organisations is now being embedded into the DNA of HPass, the international humanitarian skills recognition network now in piloting, scheduled for public launch in early 2019. Organisations who can demonstrate audited compliance with the HPass Standards for Learning or Assessment Providers will become “HPass Approved” on the system, a form of accreditation that will be signposted with Endorsement metadata baked into their badges and a distinctive visual quality mark they can display on their badge images. This is an example of a formal “accreditation-like” endorsement, but HPass badges can also be endorsed informally by peer organisations.The ultimate aim of alternative credentialing such as Open Badges is recognition, and I think that the ability to endorse badges is a big step forward towards that.

Source: Open Badge Factory

Valuing and signalling your skills

When I rocked up to the MoodleMoot in Miami back in November last year, I ran a workshop that involved human spectrograms, post-it notes, and participatory activities. Although I work in tech and my current role is effectively a product manager for Moodle, I still see myself primarily as an educator.

This, however, was a surprise for some people who didn’t know me very well before I joined Moodle. As one person put it, “I didn’t know you had that in your toolbox”. The same was true at Mozilla; some people there just saw me as a quasi-academic working on web literacy stuff.

Given this, I was particularly interested in a post from Steve Blank which outlined why he enjoys working with startup-like organisations rather than large, established companies:

It never crossed my mind that I gravitated to startups because I thought more of my abilities than the value a large company would put on them. At least not consciously. But that’s the conclusion of a provocative research paper, Asymmetric Information and Entrepreneurship, that explains a new theory of why some people choose to be entrepreneurs. The authors’ conclusion — Entrepreneurs think they are better than their resumes show and realize they can make more money by going it alone.And in most cases, they are right.If you stop and think for a moment, it's entirely obvious that you know your skills, interests, and knowledge better than anyone who hires you for a specific role. Ordinarily, they're interested in the version of you that fits the job description, rather than you as a holistic human being.

The paper that Blank cites covers research which followed 12,686 people over 30+ years. It comes up with seven main findings, but the most interesting thing for me (given my work on badges) is the following:

If the authors are right, the way we signal ability (resumes listing education and work history) is not only a poor predictor of success, but has implications for existing companies, startups, education, and public policy that require further thought and research.It's perhaps a little simplistic as a binary, but Blank cites a 1970s paper that uses 'lemons' and 'cherries' as a metaphors to compare workers:

Lemons Versus Cherries. The most provocative conclusion in the paper is that asymmetric information about ability leads existing companies to employ only “lemons,” relatively unproductive workers. The talented and more productive choose entrepreneurship. (Asymmetric Information is when one party has more or better information than the other.) In this case the entrepreneurs know something potential employers don’t – that nowhere on their resume does it show resiliency, curiosity, agility, resourcefulness, pattern recognition, tenacity and having a passion for products.My main takeaway from this isn’t necessarily that entrepreneurship is always the best option, but that we’re really bad at signalling abilities and finding the right people to work with. I’m convinced that using digital credentials can improve that, but only if we use them in transformational ways, rather than replicate the status quo.This implication, that entrepreneurs are, in fact, “cherries” contrasts with a large body of literature in social science, which says that the entrepreneurs are the “lemons”— those who cannot find, cannot hold, or cannot stand “real jobs.”

Source: Steve Blank

Does it take Trump to make badges go mainstream?

Perversely, it might take something like the Trump administration to make Open Badges work at scale. Why? Because Republicans don’t trust Higher Education:

Is support for higher ed fragmenting along political lines? It is if you believe the recent Pew poll showing Republicans’ distrust of higher ed is growing relative to Democrats (on a nearly 2-to-1 margin) is not fake news... In any case, look for Trump’s Department of Education to push on the trend toward more “practical” vocational learning and not just apprenticeships. Higher Ed Act proposals this year may push to open up federal financial aid beyond the credit-hour.Things, of course, are different in the US to the rest of the world. In Europe I think we've always had a different, and more positive, relationship to vocational education.

Source: Education Design Lab