I love it; I hate it; I resent that I need it. I wouldn’t miss it if it vanished—but of course, I also would.

I discovered this curious article via Arts & Letters Daily which I’ve only recently rediscovered, after I used to visit it, well, daily. The article is a conversation published in The Point between its editors, many of whom attended the Arts and Humanities Division at the University of Chicago. News that they have paused graduate student admissions for all departments, are trying to cut costs, and restructuring caused them to reflect on their own experience, and the importance of a graduate education in the Humanities.

As a graduate of Humanities subjects myself (Philosophy, History, Education) I found it really interesting to read Becca Rothfeld’s contribution. Universities, as I have said before, do not have a right to exist—especially in their current, neoliberal form. That’s not to say I would simply get rid of them, quite the opposite: I think everyone should have space for the kind of contemplation, reflection, and self-development that they can provide.

Although this article is about the US higher education system, my experience is of the UK approach. My parents were paid to go to university, while a generation later I was invoiced a (relatively) small amount for the privilege, and in which now my son is on the hook for a lot more. As other people have said more eloquently than I ever could, this has meant that, over my lifetime, universities have morphed from a public good into a private one. We should do something about that.

Forgive me, Father, for I do not want to have doubts about the academic humanities on the eve of their decimation—but I’m not sure that I will miss the ivory towers when they’re gone, or at least, what I will miss about them strikes me as incidental to their self-conception and their stated aims. I will miss the role they played, often despite themselves, and I will miss the people who populated them, often ambivalently and always in abominable working conditions. And it goes without saying that if the humanities ever ceased to exist, I would not merely “miss them”; I would cease to have a reason for living. But I’m not sure that the humanities could ever vanish—we need them too much, and we perpetuate them too helplessly, just by dint of being the kind of creatures we are—and I’m even less sure that the academy in its present incarnation provides the best forum for their continuation. That isn’t to say that I wouldn’t go to the barricades to protect the ivory tower, now that the philistines are at the gate. Rest assured: I plan to. But I’d rather go to the barricades for something I could stand behind with less trepidation.

What did I love about the university during my decade inside it? I loved the ideal, rarely realized, of an intellectual community—a group of people committed to thinking together rather than competing against one another for a vanishingly small spate of jobs. And I loved the promise, equally notional, that there might be a retreat from worldly preoccupations, a place reserved for thinking, just for the sheer delight of it. Above all, I loved the kind of people the university attracted (and often ended by demoralizing, if not completely destroying): people eager to pore over The World as Will and Representation line by line for over a year, people for whom the life of the mind is a necessity and, more importantly, a joy. And if I didn’t exactly love that academic humanities departments are pretty much the only durable and entrenched institutions in the anglophone world dedicated to the study and preservation of the arts, I knew that it was true. And if I downright hated that so many of us were consigned to conditions of poverty and precarity, I had no choice but to pretend our plight was justified by the project we were jointly committed to maintaining. But was it?

You’re catching me at a moment of acute skepticism. I’ve just returned from teaching at the Matthew Strother Center, a place that’s hard for me to describe in less than half a million words. In brief: five students of all ages and all professions come to a farm in the Catskills, where they stay for a week for free, without their phones or computers. They don’t know in advance what book the faculty will assign them, but they show up anyway. During the day, they work on the farm and attend a three-hour seminar. At night, they participate in “salons”: during our session, we staged a performance of Plato’s Symposium and sang an arrangement that one of the students, a retired choral director and organist in his late sixties, prepared for us. We were not expected to produce anything. The goal was the hardest and best thing in the world: to read a book together and try to understand it.

That book was The Gay Science—which is in large part about the shortcomings of the modern university. Nietzsche describes its resident specialists as “grown into their nook, crumpled beyond recognition, unfree, deprived of their balance, emaciated and angular all over except for one place where they are downright rotund.” I think I know what he means. I’ve taught Nietzsche in the university, and I’ve taught him on a farm in the Catskills, and there is no comparison.

So where does this leave me, a conflicted defender of the university, an academic exile by choice? We need humanistic institutions. The humanities are not the kind of thing we can—or would want to—do alone. But must we content ourselves with the humanistic institutions we have? Yet it isn’t obvious that the model of the Center could ever be scaled up to accommodate a whole nation, and it certainly is obvious that any broadscale change in humanistic education is a lamentably long way off. For now, for better or for worse (and I’m often convinced it’s very much for worse), the university is the best we have. I love it; I hate it; I resent that I need it. I wouldn’t miss it if it vanished—but of course, I also would.

Source: The Point

Image: Alisa Anton

What is still human in our lives lingers on in the interstices of a vast inhuman mechanism

I don’t have much time for Paul Kingsnorth, whose new book is the subject of this review by John Gray in New Statesman. But Gray’s review is itself interesting for the thoughts generated by his reading of Kingsnorth’s essays.

In particular, I found the following a concise, clear-eyed description of the world that is being shaped for us and we have no choice but to inhabit.

Instead of human-to-human relationships, our lives consist ever more of interactions with machines. The options we have in entertainment, the arts and consumer goods have expanded enormously – but what we watch, listen to and buy are algorithmically regulated commodities, increasingly generated by AI. Much of the food we eat is no longer produced by human-scale farms and reaches us processed and packaged from distant mega-corporations. What is still human in our lives lingers on in the interstices of a vast inhuman mechanism.

Source: New Statesman

This is coming from someone who’s allegedly running a company that’s building a tool that should usher in a new era where computers will replace most of human work

Well, indeed. A company that is allegedly so close to AGI does not bother spending time ensuring that adults can create erotica while releasing an AI-enabled web browser based on another company’s technology. It all seems a little desperate.

I code sites for a living (allegedly), and I honestly cannot overstate how uninterested I am in all these new browsers. Because these are not new browsers: these are Chromium frames with AI slapped on top.

The thing I found more interesting about the whole OpenAI announcement was Sam Altman tweeting: «10 am livestream today to launch a new product I’m quite excited about!». This is coming from someone who’s allegedly running a company that’s building a tool that should usher in a new era where computers will replace most of human work, where we’ll all have a super intelligence always available in our pockets, ready to dispense infinite wisdom.

And yet he’s quite excited about a fucking Chromium installation with AI slapped on top of it. I guess building an actual browser, from scratch, is still a task so monumentally difficult that even a company that is aiming for super-intelligence can’t tackle it.

Source: Manuel Moreale

Everyone planting the same crops of “impact frameworks,” all aiming for growth, all tending the same metrics of success.

I’d argue that much of what Tom Watson talks about in these four thought-provoking posts (AI summaries below) relates to my work on ambiguity — especially my article On the strategic uses of ambiguity. There’s also a good dose of systems thinking in there, too.

People as Code (Part 1) Tom Watson’s opening essay argues that society could re‑organise itself using the same collaborative, modular logic that drives open‑source software. By treating “people as code,” he imagines communities and organisations as contributors to a shared repository of social infrastructure, building frameworks that evolve through openness, documentation, and iteration. Borrowing from the culture of digital development, he urges philanthropy and the social purpose sector to act as maintainers of systems where people co‑create and adapt the “source code” of collective good rather than operating in isolation.

People as Code 2 – Collapse, Rewild, Regenerate This follow‑up re‑examines the original optimism through the lens of generative AI’s cultural saturation. Watson warns that algorithmic convergence and efficiency culture flatten creativity and produce brittle systems, both digital and organisational. Using the metaphor of a forest ecosystem, he advocates for “rewilding” our sectors—embracing plurality, slowness, and relational infrastructures more like mycelial networks than monocultures. His call to “keep a little wildness in the loop” positions regeneration, uncertainty, and imperfection as essential design principles for sustainable systems.

People as Code 3 – Quantum Uncertainty Extending the series’ metaphoric vocabulary, this essay draws from quantum theory to explore how embracing uncertainty can help organisations remain responsive and creative in complex environments. Just as particles exist in superposition until observed, Watson suggests that ideas and social systems should be allowed to remain indeterminate long enough for new possibilities to emerge. He frames quantum uncertainty as an ethical stance—one that resists premature definition and instead values curiosity, multiplicity, and relational dynamics over predictability.

People as Code 4 – Entropic Systems The final piece introduces entropy as a metaphor for organisational vitality. Instead of treating disorder as decay, Watson views it as the precondition for renewal and learning. He suggests designing “entropic systems” that can adapt, self‑balance, and evolve through cycles of breakdown and regeneration, much like living ecologies. In practical terms, this means loosening control, distributing agency, and regarding instability not as failure but as evidence of life within complex, evolving networks.

The problem, of course, is that ‘rewilding’ means “consciously doing something different than what we’re doing now” and I don’t think that as a society we have the reflective apparatus to allow that to happen. We live in extremely shallow times. As Tom says in the second article, “Everyone planting the same crops of “impact frameworks,” all aiming for growth, all tending the same metrics of success.”

Image: Suzanne Rushton

The only exit to be found is in beating a path through the wildfires of postmodernity to new technicities.

This interview with AA Cavia, a “philosopher of computation” is a tough read in places as it’s so semantically dense. Nevertheless, this section I’ve excerpted at the end makes a really good point: what counts as ‘creativity’ changes over time, and future creativity is likely to involve significant amounts of AI.

That means instead of Luddism, we need to find other ways of organising against Capital. Not trying to put the genie back in the bottle.

This decentering of the human should not be conflated with dehumanizing tendencies that center capital, empire or the war machine over human welfare. It’s instead an invitation to develop new norms with which we can rethink the human and its place in our intellectual tradition, so I see it as a political project with emancipatory potential.

Seen through this lens, AI is a project of transition of the human, a transgression encoded into its origins in Turing’s imitation game, a test which machines should not be seen to pass, but which instead humans are inevitably set up to fail. And in this failure of self-recognition I see some positive potential. In this sense, the only alignment problem I think we should be tending to is that between humanity and capital, a conflict in which computation has been weaponised.

In this regard, I reject narratives which posit a total subsumption of computation, or indeed any paradigmatic technology, under capital. If we look at the backlash against AI, which pits human creativity against generative models, it appears to be guided by archaic notions of creativity, which suffer from residues of said twentieth century humanism. As a result of this discourse, Luddism is rampant, particularly in the academic left. Even a cursory reading of the philosophy of technology, take Simondon’s discussion on the dualism of organism and mechanism as taken up by Yuk Hui, will suggest a completely different way of approaching such questions.

The notion of authorship has been shifting continuously throughout human history of course, and the answer is never to down tools and protect what we have, but rather to forge new tools.

As creative practitioners, there are many ways I think we should be organizing against capital, including new ownership and rights models, but Luddism isn’t one of them. The history of art and the history of technology are one and the same; they are intricately braided. Without the invention of a technique such as oil painting we wouldn’t have Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece. Art is hatched in that friction between human experience and technical practices. On this point I would take heed of Rimbaud’s advice: one must be absolutely modern.

If contemporary reality feels like a season in hell, the only exit to be found is in beating a path through the wildfires of postmodernity to new technicities.

Source: Le Random

Image: Elise Racine

Think of this as the early stages of a wartime economy

Nathan Rice’s argument in this piece is that AI is, effectively, a proxy war with China and that the US is way behind. As a result — for many, reasons, including ego, the Silicon Valley AI companies' profits are being guaranteed by the American taxpayer.

That’s a dangerous bet, especially when (as he points out near the start of the article) that “If it wasn’t for AI investments, it’s likely the United States would be in a recession right now.” I don’t think that AI is going to completely transform economies in the timeframe that boosters are talking about and, therefore, agree with Rice that the deflation or bursting of the bubble is going to be very tough.

I just hope that we, in the UK (and Europe) have the good sense to realise that good things happen slowly and bad things happen fast.

Between Elon Musk, David Sacks, Sriram Krishnan, Peter Thiel and his acolyte J.D. Vance, Trump has been sold the story that AI dominance is a strategic asset of vital importance to national security (there’s probably also a strong ego component, America needs “the best AI, such a beautiful AI”). I’m not speculating, this is clearly written into the BBB and the language of multiple executive orders. These people think AI is the last thing humans will invent, and the first person to have it will reap massive rewards until the other powers can catch up. As such, they’re willing to bend the typical rules of capitalism. Think of this as the early stages of a wartime economy.

[…]

How much of a “war” this is is debatable; if you think we’re going to reach peak AI with GPT6, it’s a nothingburger, but if you believe AI is the next industrial revolution, that framing is fairly accurate, as failure to adapt would be an economically existential threat. The Chinese will not pull back on AI investment, and because of their advantages in robotics and energy infrastructure, they don’t have to. Unlike us, they’re able to do it sustainably. US households don’t have sufficient surplus income to support consumer robotics at scale and our industrial base is likely insuffient to drive robotics investments at the scale required, and with the administration’s crusade against solar energy and America’s unwillingness to build nuclear power, we’re at a crippling disadvantage in the energy race. We have a head start in AI, but China can train for less, soon they’ll have more training capacity, and they’ll be able to use their lead in robotics to capture far more economic value from AI than we will. That means the longer the AI race drags on, the more likely China is to beat us. The people in power aren’t willing to risk that outcome, and they’ve been bewitched by the idea of being the only ones to have superintelligence, so they’re willing to go all-in to win big and fast.

[…]

Where does all this leave us? For one, you better hope and pray that AI delivers a magical transformation, because if it doesn’t, the whole economy will collapse into brutal serfdom. When I say magic here, I mean it; because of the ~38T national debt bomb, a big boost is not enough. If AI doesn’t completely transform our economy, the massive capital misallocation combined with the national debt is going to cause our economy to implode.

If you think I’m being hyperbolic calling out a future of brutal serfdom. Keep in mind we basically have widespread serfdom now; a big chunk of Americans are in debt and living paycheck to paycheck. The only thing keeping it from being official is the lack of debtor’s prison. Think about how much worse things will be with 10% inflation, 25% unemployment and the highest income inequality in history. This is fertile ground for a revolution, and historically the elites would have taken a step back to try and make the game seem less rigged as a self-preservation tactic, but this time is different. As far as I can tell, the tech oligarchs don’t care because they’re banking on their private island fortresses and an army of terminators to keep the populace in line.

Source: Sibylline Software

The quiet normalisation of insecurity as the price of ‘flexibility’

This is a long and very good post by Alex Evans, whose main concern is the voluntary and charity sector (VCS). Although he goes on to give a potted history of the Black Death and feudalism, as well as outlining the promise of universal basic income, it’s his analysis of what’s happening with freelancers and the diminishing middle class in the UK which interests me.

Pre-pandemic, and pre-Brexit things were much better. Every time I meet up with people who are freelancers, part of worker co-ops, etc. the conversation quickly turns to the same thing: what’s going on? I’ve variously blamed: AI, the number of elections in 2024, over-hiring during the pandemic, Brexit, and the super-rich hoarding money.

The truth is, it’s probably all of those things and more. But I think that Evans is correct to say that the VCS is the canary in the coalmine for the next recession. 2025 has been terrible but let’s hope that next year isn’t even worse…

What we’re watching in the voluntary sector mirrors patterns across the wider economy: the disappearance of mid-level roles, the rise of short-term contracts, and the quiet normalisation of insecurity as the price of ‘flexibility’. As ever, I’m not so interested in the ‘inside baseball’ trade talk. I’m much more interested in how this maps to wider changes in our society, economy, and culture. For some time, there has been a hollowing out of middle incomes in the West - people in clerical, skilled manufacturing jobs. In the VCS this seems to be expanding further up the tree and into senior roles. I think we are canaries in the mineshaft of the next recession (or even crash) likely to engulf the wider economy before long.

[…]

[T]here’s always a danger that we welcome a new flexibility without noticing that much of this is a result of massive sector contraction. Some people are finding that there is no longer an alternative, as restricted funding, refusal to pay for management costs, and wider cuts risk creating a new precariat where managers/ specialists used to have job security. Others - especially fundraisers & CEOs - are fleeing toxic burnout cultures.

[…]

The new precarious middle classes have been the subject of concern for commentators and economists for some time. And it is likely that this sense of increased anxiety and middle class precarity adds to the rise of voting for right wing parties in groups who might normally find them rather too déclassé. When you lose a property owning middle class, more and more of that wealth is sucked up to the super-wealthy. Economists and popular economic commentators like Gary Stevenson have warned about the hollowing out of the middle classes, as resources get siphoned out of the working and middle classes and into an ever-increasing share of wealth for the super-wealthy, whether corporate or individual.

[…]

A recent study by the OECD shows that the middle classes, faced with stagnant incomes and rising costs, are becoming less able to save and falling into debt. We also know that home ownership is becoming less and less likely for even middle class households. Of course the ‘middle class’ is constantly shifting, and has many nooks and crannies, and levels of wealth, autonomy, power and privilege. Where it begins and ends is a constant source of debate and discussion. And many would point out that most of the people who we describe as ‘middle class’ in the UK are in actual fact, much like in the US, really ‘working class’. They may have the trappings of respectability, perhaps some savings, may (decreasingly) own their own home, or may have been to university, but as the OECD points out, all of those things are being erased. We’re seeing downward social mobility over the generations (I’ve seen this in my own family). And the fundamental of having to sell labour to those who extract profit is an economic characteristic of most ‘middle class’ experiences, until we reach the upper limits where we may find those who have invested in property, or enjoy some level of hereditary wealth.

Source: Barely Civil Society

Image: Vitaly Gariev

A single point of failure for large swaths of critical services

The way I found out about this morning’s Amazon Web Services (AWS) outage was when my Signal messages wouldn’t send. We had to use Google Meet instead of Zoom for our weekly WAO meeting but everything was working again by lunchtime.

Still, it’s a reminder that not only is a huge infrastructure build-out such as AWS a single point of failure, they’re also an easy way for those that wish to control the internet to do so.

A massive cloud outage stemming from Amazon Web Services’ key US-EAST-1 region, its hub in northern Virginia, near the US Capitol, caused widespread disruptions of websites and platforms around the world on Monday morning. Amazon’s main ecommerce platform and other properties, including Ring doorbells and the Alexa smart assistant, suffered interruptions and outages throughout the morning, as did Meta’s communication platform WhatsApp, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, PayPal’s Venmo payment platform, multiple web services from Epic Games, multiple British government sites, and many others.

[…]

AWS has suffered other large-scale outages, including a major incident in 2023. Reliance on central cloud services from giants like AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Services has, in may ways, improved cybersecurity and stability around the world by creating a baseline of guardrails and best practices for all customers. But this standardization comes with major trade-offs, because the platforms become a single point of failure for large swaths of critical services.

Source: WIRED

Image: israel palacio

Put your things out in the world, let them help the people they can help

I love this from Dan Sinker, who together with his co-host Maureen Johnson, has just put out the 400th episode of their podcast Says Who — which they’d only planned to run for eight episodes!

Side note: I miss recording a podcast. While I’ve put out a few microcasts recently, there’s nothing like having a co-host! It’s been a year since Laura and I put out a season of The Tao of WAO

When times are hard—and they were then and they sure as shit are now—one of the best things you can do is build things with your friends. Build things that can help people get through it, even if that just means you. Because it almost always isn’t just you. Put your things out in the world, let them help the people they can help. You never know where it might lead.

Source: Dan Sinker

Image: Katarzyna Pypla

Philosophy always begins in mood

The latest issue of New Philosopher magazine is on the theme of ‘Emotion’ so, as you can imagine, there’s quite a few mentions of Stoic philosophers. However, I want to share three parts which really struck a chord with me. Together, they’ve helped me reflect on the relationship between my moods and emotions (which I seem to feel quite strongly compared to some people) and philosophy — which is usually considered as a cold, rational pursuit.

The first is from Antonia Case’s essay entitled ‘The Meaning of Moods’ (p.19-20) in which she talks about the importance of matching what you read with your current mood:

Moods are mysterious because they aren’t necessarily tied to anything specific, nor can we reliably predict which mood will show up. You might wake up to a beautiful sunny day — it’s Sunday, with nothing much planned — and you feel a brooding unrest.

[…]

Philosopher Lars Svendsen, in Moods and the Meaning of Philosophy, argues that philosophy always begins in mood. Our mood prompt the questions we ask.

[…]

Svendsen ponders why certain philosophers speak to us more powerfully than others. He admits he has never felt quite “at home” in Spinoza’s writings as he has with Kant or Wittgenstein. Despite understanding Spinoza intimately and lecturing on his work, he wonders: “Could it be that I have simply failed to enter these texts in the proper mood?” Not only is a philosophyical text infused with the mood of its author; when we read it, we too approach it in a particular mood. “If your mood and the mood of the text are at odds, there is the risk that the text simply will not ‘speak’ to you,” Svendsen observes.

The next extract is from Tom Chatfield’s piece ‘Happiness, quantified’ (p.34) where, along with reflecting on some Buddhist wisdom about ‘aliveness’, he discusses how all emotions are part of who we are:

[T]he lesson I struggle to teach my children — because I am also struggling to learn it myself — is that the sadness and anger can be as appropriate and important as the love and joy. They are not enemies to be overcome or data to be processed, but part of who we are. The trick is not to will or wish them away, but to notice them (to be fair, the Inside Out movies help with this one).

The final thing I want to share is from an interview with the psychologist and neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett (p.85) who shares some really interesting insights about the granularity of categories in which we place our emotions:

Granularity is really about the capacity to construct categories that are specifically tailored to the situation that you are in… [W]hen your brain is predicting, it is remembering the past, past instances that are similar to the present. It’s constructing a category. A category is a group of things which are similar enough to each other to be interchangeable or to be used for the same function. So your brain is always constructing categories on the fly, instantaneously or extemporaneously. And the ability to construct a category in a very situated way for a specific purpose is the concept of emotional granularity. Granularity is not about labelling; it’s about what you do and feel. Is the instance of emotion specific enough to the situation that you can engage in a behaviour that will allow you to function well in that situation.

I mean, when you feel like shit, what do you do when you feel like shit? That’s not a very specific category, right? If somebody has a single category for anger, that’s not very helpful, because in our culture, an instance of anger can be unpleasant or pleasant. Anger can involve physical movement or remaining still. Sometimes you shout in anger. Sometimes you smile in anger. Sometimes you sit quiety and plot the demise of your enemy of anger. The evidence shows that blood pressure can rise, fall, or stay the same in anger. The variation is not random. It is structured by the situation and the categories your brain is capable of making. The predictions that your brain makes when it’s constructing an instance of anger begin with allostasis, which support skeletomotor movements and give rise to felt experience.

So, basically, the more granular you are, the more tailored your actions and emotional experience will be to the specific situations you are in, the more varied your emotional life will be. On the other hand, too much specificity — and not enough generalisation — is also not helpful. So, it’s a metabolic balancing act: categories with too much generalisation are not helpful, and categories that are too specific are not helpful. There’s a sweet spot between simplification and complexity in emotional life.

Source: New Philosopher magazine

Image: Nik

I will continue living the writing life, even if it doesn’t lead to fame or fortune

If you want people to pay attention to your ideas these days, you really need to put things in video format. Ideally one that less than 30 seconds long and includes something funny or unexpected. It helps with the algorithm.

At the end of last year, The Economist published an article entitled Are adults forgetting how to read? which concluded “You do not need a first-rate mind to sense trouble ahead.” Stowe Boyd riffs on this and, like me, resists the temptation to ‘pivot’ to video with every fibre of his being.

The decline of literacy and the eclipse of reading, combined with algorithmic feeds breaking the ‘traditional’ follower model of the blogosphere and pre-TikTok social media, may be the death of newsletters, and ultimately, writing.

[…]

In the near term, while the streams of video and AI slop seemingly are clogging every available orifice in the body public, I will continue living the writing life, even if it doesn’t lead to fame or fortune.

Source: workfutures.io

Image: Thomas Franke

Most decisions are like hats

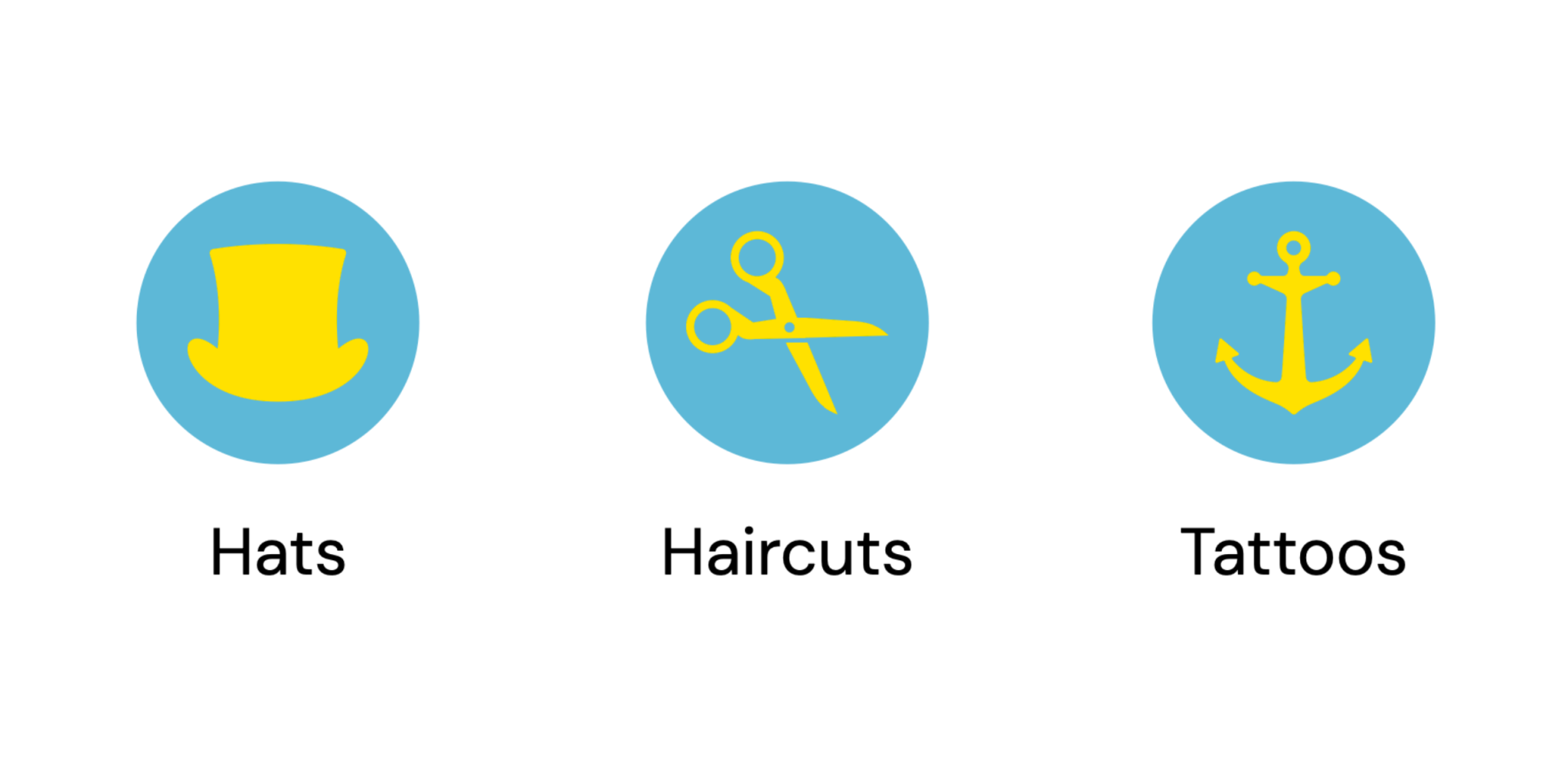

I like things that come in threes, and this in particular seems like a useful heuristic for helping categorise a change process. Emily Webber riffs on an original idea by James Clear: is this like a hat, a haircut, or a tattoo?

The language that I tend to use with clients around this, informed by Sociocracy is whether a proposal or idea is “good enough for now, and safe enough to try.” Going forward, I think I might couple that with these metaphors.

Most decisions are like hats. Try one and if you don’t like it, put it back and try another. The cost of a mistake is low; the decision is made quickly and can be easily reversed. Teams should be able to make these on their own and share the results fairly quickly.

[…]

Some decisions are like haircuts. You can fix a bad one, but reversing it can take some effort, and you might need to live with it for a while.

[…]

A few decisions are like tattoos. Once you make them, you have to live with them. Reversing them would be very expensive and painful, and not always possible.

Source & image: Emily Webber

Referencing an imaginary 'social contract' that is violated by AI

I just wanted to express full agreement and solidarity with Stephen Downes' view of how and why we should put things on the internet (emphasis added).

“The open web is under attack by AI bots that steal web publishers' content,” writes Nate Hake on some travel blog site. Normally I wouldn’t bother, but it’s referenced by Paul Prinsloo and is yet another article referencing an imaginary ‘social contract’ that is violated by AI. “In the past,” writes Hake, “search engines and platforms sent real human users to websites. Today, they increasingly send AI bots instead.” But search engine traffic matters only if you run advertisements on your site; for people like me, the traffic sent by Google, say, is just traffic I have to pay for. That’s why I’m happy to syndicate my site on RSS and social media; it’s good for me if people read my stuff elsewhere. So I don’t mind if AI bots crawl my site (provided they don’t amount to a DOS attack) and my only real desire would be to have AI credit me with an idea if it happens to originate with me. But even this isn’t part of any ‘social contract’. Sure, if you don’t want AI to crawl your site, block it (or turn over control of the internet to Cloudflare, your call). To me, sharing the ideas is what counts, and sharing is not transactional and not based on any social contract.

Source: Downes.ca

Image: Gaku Suyama

You'd have to be naive to be surprised

‘Dead internet theory’ is a conspiracy theory which, like most conspiracy theories, is based on a vibe and a kernel of truth rather than anything resembles actual fact. It asserts that “since around 2016 the Internet has consisted mainly of bot activity and automatically generated content manipulated by algorithmic curation, as part of a coordinated and intentional effort to control the population and minimize organic human activity.”

When you see videos like this one, however, you realise that — especially on some social networks — there is a lot of algorithmic manipulation. However, it’s more to do with influence (commercial, political) than “controlling the population” and relies, like most things, on economic incentives to act in a particular way.

Source: Reddit

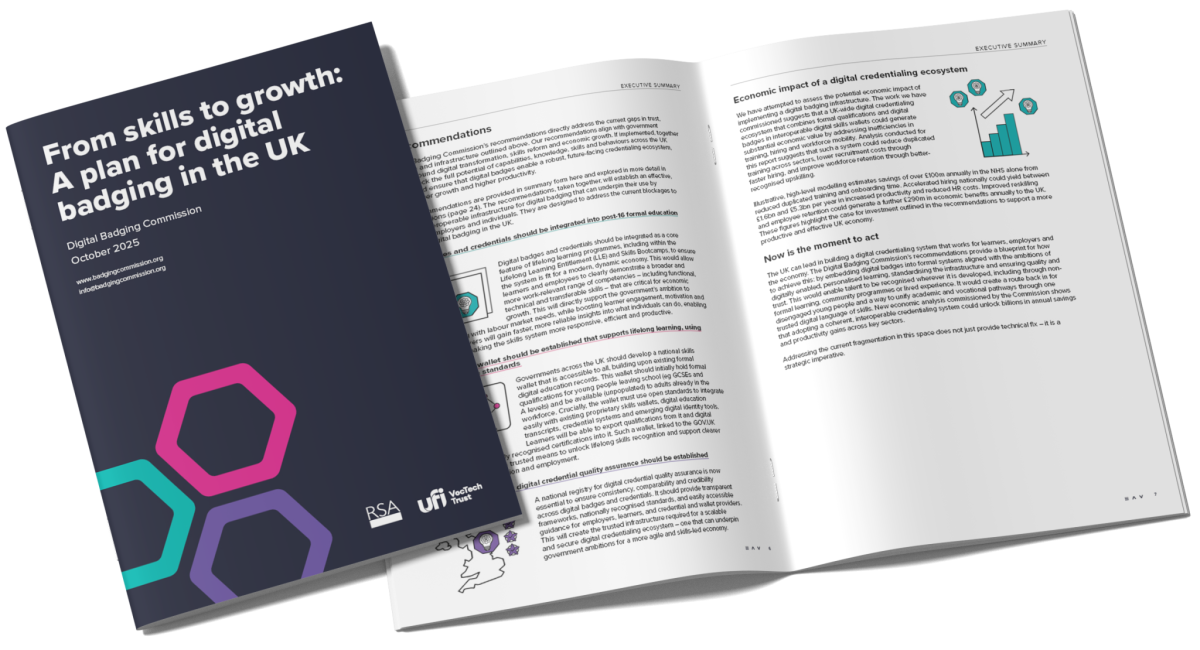

Some thoughts on the Digital Badging Commission's report

I was going to spend some time writing a detailed blog post about a new report from the Digital Badging Commission entitled From skills to growth: A plan for digital badging in the UK. But instead of damning it with faint praise, I’ve decided that all I’ve got to say fits into some basic traffic light feedback:

🟢 It’s good that the report stresses the importance of open standards and interoperability, and suggests that various official bodies explore using badges.

🟡 It seems there’s a fundamental conflation of quality assurance and technical validation (the word ‘registry’ suggests the latter but explicitly used in the context of the former). Also, using terminology (CLR, LER) which is only really used in the US really muddies the water for the reader.

🔴 Despite language of empowerment and recognition towards the start of the report, the third recommendation merely cements the status quo of ‘vetted providers’ being the providers of ‘skills.’

I got involved in Open Badges 14 years ago because of the standard’s revolutionary, decentralised potential. The various iterations and improvements have already led to massive innovation across the world with hundreds of millions of badges being issued each year. The role of official bodies is therefore coordination not imposition.

TL;DR: I think the first two recommendations are… fine. It’s the third one which I think is problematic.

The Digital Badging Commission’s recommendations directly address the current gaps in trust, coordination and infrastructure outlined above. Our recommendations align with government ambitions around digital transformation, skills reform and economic growth. If implemented, together they will unlock the full potential of capabilities, knowledge, skills and behaviours across the UK workforce and ensure that digital badges enable a robust, future-facing credentialing ecosystem, driving stronger growth and higher productivity.

[…]

1. Digital badges and credentials should be integrated into post-16 formal education and training Digital badges and credentials should be integrated as a core feature of lifelong learning programmes, including within the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) and Skills Bootcamps, to ensure the system is fit for a modern, dynamic economy. This would allow learners and employees to clearly demonstrate a broader and more work-relevant range of competencies – including functional, technical and transferable skills – that are critical for economic growth. This will directly support the government’s ambition to better align learning with labour market needs, while boosting learner engagement, motivation and progression. Employers will gain faster, more reliable insights into what individuals can do, enabling smarter hiring and making the skills system more responsive, efficient and productive.

2. A national skills wallet should be established that supports lifelong learning, using interoperable open standards Governments across the UK should develop a national skills wallet that is accessible to all, building upon existing formal digital education records. This wallet should initially hold formal qualifications for young people leaving school (eg GCSEs and A levels) and be available (unpopulated) to adults already in the workforce. Crucially, the wallet must use open standards to integrate easily with existing proprietary skills wallets, digital education transcripts, credential systems and emerging digital identity tools. Learners will be able to export qualifications from it and digital badges and professionally recognised certifications into it. Such a wallet, linked to the GOV.UK One Login, will provide a trusted means to unlock lifelong skills recognition and support clearer pathways through education and employment.

3. A national registry for digital credential quality assurance should be established A national registry for digital credential quality assurance is now essential to ensure consistency, comparability and credibility across digital badges and credentials. It should provide transparent frameworks, nationally recognised standards, and easily accessible guidance for employers, learners, and credential and wallet providers. This will create the trusted infrastructure required for a scalable and secure digital credentialing ecosystem – one that can underpin government ambitions for a more agile and skills-led economy.

Source: Digital Badging Commission

But what a time to be alive, to be living though all of this, inside the churn.

I can’t say that I have the same response to the ‘voltage of the age’ as Jay does, but I recognise the reference to Tennyson. My anxiety, which I’m also dealing with, makes me want to withdraw and let other people figure it out. There’s only so much storm my small boat can take.

Every single day right now it seems like I’m waking up in the morning to some new piece of bullshit. Some new AI thing, some new crypto thing happening, some new insane crypto AND AI thing, politics is mad, war is happening and only going to get worse every where, a genocide is playing out in full view of the world, biosphere collapse, the news of AMOK collapse risk, there is no end to the horrors.

The sea is so very big and my boat is so very small.

But what a time to be alive, to be living though all of this, inside the churn.

It’s not that I want any of this to happen. It’s just can help but watch. As I said to someone the other day, my body keeps registering the ‘voltage of the age‘. Translating my former feelings of anxiety into something like exhilaration from the acceleration around me.

[…]

The only response to this whole unfolding crisis is to stay fully awake inside the gyre. To resist being programmed into unawareness even as the slop machine churns out it’s dreams. We may not be able to slow the velocity of the ongoing circle, but we can at least pay attention to the circle itself, not it’s products. We can name the feeling as ‘voltage of the age’, and refuse to forget that we are in fact still here, alive, and can care for one another, as it’s all happening right now.

Source: thejaymo

Image: Thomas Kelley

It is the opposite of a memory palace. Not at all a wunderkammer.

Everyone works differently, which becomes evident when you observe writers' favourite writing spots. In this post, the author Warren Ellis talks about his idea space which doesn’t have to be ordered, tagged, and categorised.

One of the reasons I put so much stuff on the web rather than into notebooks or files that only I can access is that it’s often easier to search a keyword plus my name to remind myself what I’ve said over the years.

Also, to me at least, serendipity is more important than categorising everything perfectly. I know what I’m like: I’d end up re-categorising things endlessly…

I’m assembling a little idea space I want to do some work in. For other people, I suppose this is like moodboarding – and I always encourage artists to show me their moodboards for the areas they’re currently interested in. For me, it’s a bit more messy and cobwebby. It’s what I want to talk about and how I want to talk about it. There’s no method, protocol, routine or discipline beyond making myself sit with an open notebook and thinking into it. Which also involves searching my memory. Sorting through the calamitous disarray of drawers and cupboards in my head for bits of films and half-remembered lines and barely recalled posters and graphics. It is the opposite of a memory palace. Not at all a wunderkammer. Anyone who’s seen my actual physical office will get the idea. Weirdly, I discover things better when they’re all over the place. And I accumulate a hundred new things into the piles every day, and covet more.

Source: Warren Ellis

Image: Nechirwan Kavian

A design philosophy that treats users as citizens of a shared digital system rather than cattle

I’m taking this week off social networks, which for me means Mastodon, Bluesky, and LinkedIn. I’ve realised it really doesn’t help with my anxiety to be bombarded with endless stuff about AI, war, and spicy takes about the latest online drama.

As this article by James O’Sullivan in NOEMA discusses, the dream of mass social media has ended and we now live in its ruins. Engagement is down, yet most people get their “news” from social media. We live in a very strange world where people realise what they consume isn’t reliable but do so anyway.

Coincidentally, I’d spent some time reacquainting myself with Are.na earlier today before reading this post. It influenced my design of MoodleNet, the digital commons where communities curated collections of resources. What I like about Are.na is that it’s ‘social’ while still being appropriately weird and not focused on influence.

See also Bonfire from the remnants of the MoodleNet team and which, unlike Are.na, is part of the Fediverse. We should decide who we want to be first, and then choose our tools and networks based on that choice, rather than the other way around.

The problem is not just the rise of fake material, but the collapse of context and the acceptance that truth no longer matters as long as our cravings for colors and noise are satisfied. Contemporary social media content is more often rootless, detached from cultural memory, interpersonal exchange or shared conversation. It arrives fully formed, optimized for attention rather than meaning, producing a kind of semantic sludge, posts that look like language yet say almost nothing.

[…]

While content proliferates, engagement is evaporating. Average interaction rates across major platforms are declining fast: Facebook and X posts now scrape an average 0.15% engagement, while Instagram has dropped 24% year-on-year. Even TikTok has begun to plateau. People aren’t connecting or conversing on social media like they used to; they’re just wading through slop, that is, low-effort, low-quality content produced at scale, often with AI, for engagement.

And much of it is slop: Less than half of American adults now rate the information they see on social media as “mostly reliable”— down from roughly two-thirds in the mid-2010s. Young adults register the steepest collapse, which is unsurprising; as digital natives, they better understand that the content they scroll upon wasn’t necessarily produced by humans. And yet, they continue to scroll.

The timeline is no longer a source of information or social presence, but more of a mood-regulation device, endlessly replenishing itself with just enough novelty to suppress the anxiety of stopping. Scrolling has become a form of ambient dissociation, half-conscious, half-compulsive, closer to scratching an itch than seeking anything in particular. People know the feed is fake, they just don’t care.

[…]

These networks once promised a single interface for the whole of online life: Facebook as social hub, Twitter as news‑wire, YouTube as broadcaster, Instagram as photo album, TikTok as distraction engine. Growth appeared inexorable. But now, the model is splintering, and users are drifting toward smaller, slower, more private spaces, like group chats, Discord servers and federated microblogs — a billion little gardens.

[…]

But the old practices are still evident: Substack is full of personal brands announcing their journeys, Discord servers host influencers disguised as community leaders and Patreon bios promise exclusive access that is often just recycled content. Still, something has shifted. These are not mass arenas; they are clubs — opt-in spaces with boundaries, where people remember who you are. And they are often paywalled, or at least heavily moderated, which at the very least keeps the bots out. What’s being sold is less a product than a sense of proximity, and while the economics may be similar, the affective atmosphere is different, smaller, slower, more reciprocal. In these spaces, creators don’t chase virality; they cultivate trust.

[…]

This isn’t about making platforms needlessly cumbersome but about distinguishing between helpful constraints and extractive ones. Consider Are.na, a non-profit, ad-free creative platform founded in 2014 for collecting and connecting ideas that feels like the anti-Pinterest: There’s no algorithmic feed or engagement metrics, no trending tab to fall into and no infinite scroll. The pace is glacial by social media standards. Connections between ideas must be made manually, and thus, thoughtfully — there are no algorithmic suggestions or ranked content.

[…]

[T]here is a possible future where a user, upon opening an app, is asked how they would like to see the world on a given day. They might choose the serendipity engine for unexpected connections, the focus filter for deep reads or the local lens for community news. This is technically very achievable — the data would be the same; the algorithms would just need to be slightly tweaked — but it would require a design philosophy that treats users as citizens of a shared digital system rather than cattle. While this is possible, it can feel like a pipe dream.

Source: NOEMA

Image: Daria Nepriakhina

Ratcheting up the risks of a possible AI bubble by inflating the market and binding the fates of numerous companies together

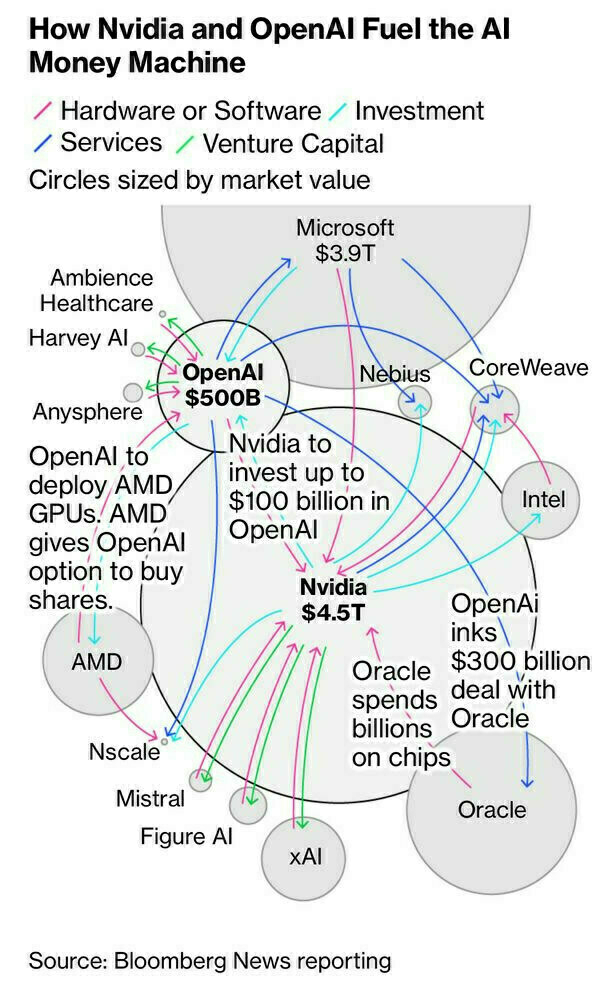

This diagram has been shared multiple times in the networks of which I’m part, but I’m mainly including it here as a form of bookmarking for future reference. There have been plenty of articles about AI being a ‘bubble’ this week but as Stowe Boyd points out, “even if there is an AI bust in the near-term, it doesn’t mean there won’t be an AI-dominated economy in the future.”

Never before has so much money been spent so rapidly on a technology that, for all its potential, remains largely unproven as an avenue for profit-making. And often, these investments can be traced back to two leading firms: Nvidia and OpenAI. The recent wave of deals and partnerships involving the two are escalating concerns that an increasingly complex and interconnected web of business transactions is artificially propping up the trillion-dollar AI boom. At stake is virtually every corner of the economy, with the hype and buildout of AI infrastructure rippling across markets, from debt and equity to real estate and energy.

The companies, which ignited an AI investment frenzy three years ago, have been instrumental in keeping it going by inking large and sometimes overlapping partnerships with cloud providers, AI developers and other startups in the sector. In the process, they’re now seen as playing a key role in ratcheting up the risks of a possible AI bubble by inflating the market and binding the fates of numerous companies together. OpenAI alone has now struck AI computing deals with Nvidia, AMD and Oracle Corp. that altogether could easily top $1 trillion. Meanwhile, the AI startup is burning through cash and doesn’t expect to be cash-flow positive until near the end of the decade.

Source & image: Bloomberg

Government IDs, are becoming hacker targets with bad actors aware of the high volume of sensitive data

I spent a lot of Friday working through the ramifications of the UK’s Online Safety Act (OSA) for a client. Although I’m sure the OSA wasn’t designed as such, it’s likely to have a chilling effect on free speech as it places so much of a burden on those running community platforms.

As a result, I should imagine that, instead of using Open Source software and creating a bespoke environment, many groups will end up using platforms provided by larger tech companies. This means their users will be subject to whatever age verification process that the tech company has chosen.

In the case of Discord, which is used by many communities, that means biometric details. It’s pretty bad that a hack has meant the leak of these details. Of course, the best thing is not to store these centrally in the first place.

Critics will assume that this is another reason not to push ahead with digital ID. But, actually, the opposite is true. Legislation such as the OSA means that providers have to implement solutions that store copies of things like passport details. With government-provided digital IDs, it’s actually the identifier that is held centrally: the biometrics stay on your device.

Some countries, including the UK, require social media and messaging providers to carry out age checks to ensure child safety. In the UK this has been the case since July under the Online Safety Act. Cybersecurity experts have warned of a risk that some providers of such checks, which can require government IDs, are becoming hacker targets with bad actors aware of the high volume of sensitive data.

“Recently, we discovered an incident where an unauthorised party compromised one of Discord’s third-party customer service providers,” Discord said in a statement. “The unauthorised party then gained access to information from a limited number of users who had contacted Discord through our customer support and/or trust and safety teams … Of the accounts impacted globally, we have identified approximately 70,000 users that may have had government ID photos exposed, which our vendor used to review age-related appeals.”

Source: The Guardian

Image: Evgeniy Alyoshin