The Woodblock Prints of Utugawa Hiroshige

I bumped into my old Physics teacher over the holidays, and found that he still has a website about Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. He’s the reason I started liking Japanese art — and the reason I created my first website, aged 17. Thanks, John!

Source: The Woodblock Prints of Utugawa Hiroshige

Image: Fireworks at Ryōgoku

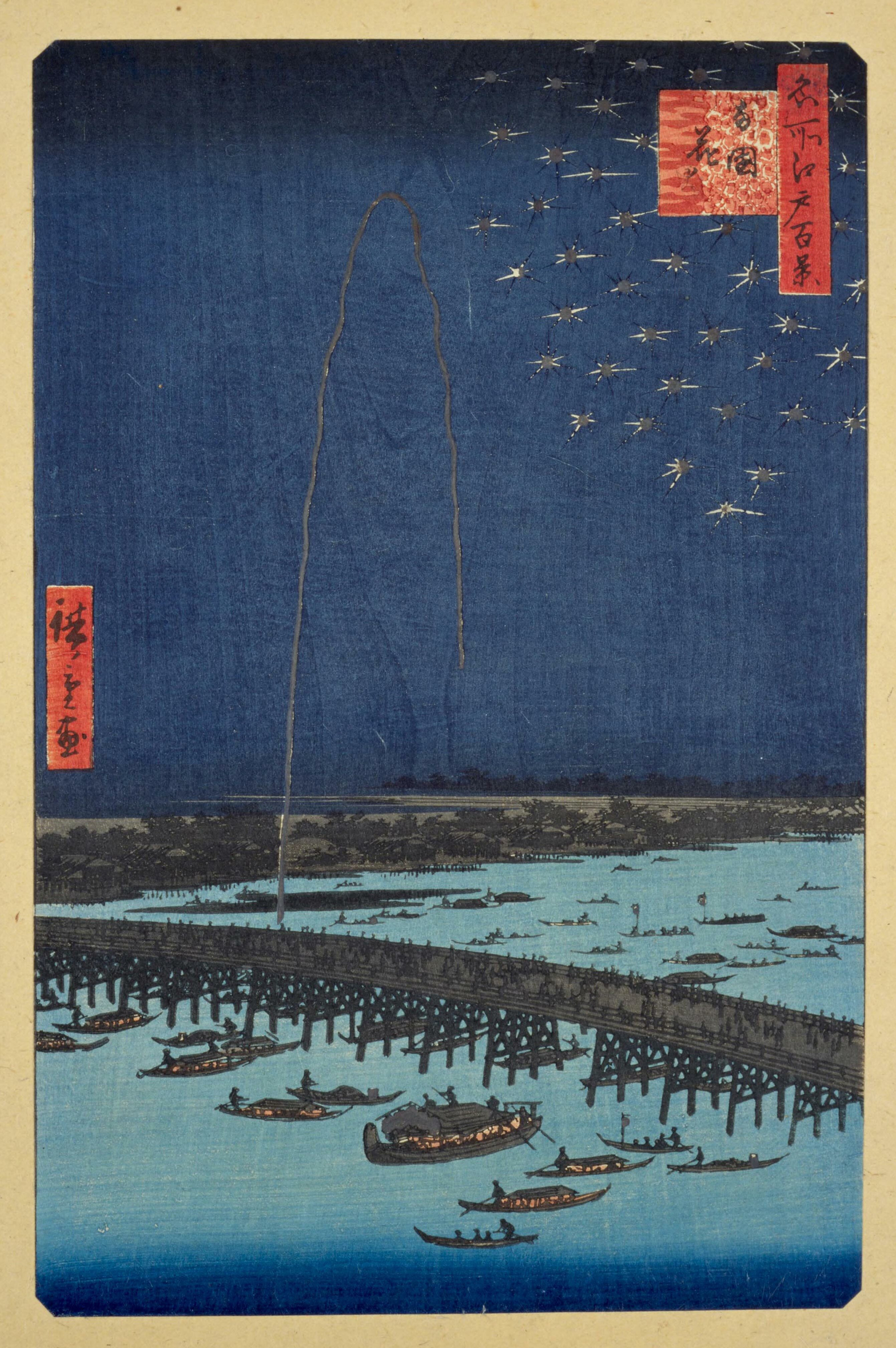

The rise of entrepreneurial heroism

This essay which mixes philosophical reflections, a new word, and popular culture is like catnip for me. In it, W. David Marx argues that we’ve essentially redefined what a “genius” means.

Instead of the lone artist starving in the garret, geniuses these days are those like Taylor Swift who fuse art and business for (huge) commercial success. As Marx argues in his conclusion “the designation of certain people as geniuses has long-term consequences” as it affects future behaviour. Without people doing things differently then, as he quotes John D. Graham as saying, “all the cultural activities of humanity would soon degenerate into clichés.”

Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky built his theory of art around the idea of ostranie — artworks that “defamiliarize” the familiar. In his book The Prison-House of Language, Frederic Jameson explains that ostranie-based art is “a way of restoring conscious experience, of breaking through deadening and mechanical habits of conduct.” And even when art fails to achieve full mind-shifts, its strangeness can at least be a source of new stimuli. Avant-garde artists in the 20th century believed art should always be a curveball; a fastball is not art.

[…]

In this, Swift offers us something new: She’s an anti-Kantian genius. Her work is always “direct” and “relatable” — no curveballs, no ostranie. Her constant deployment of existing conventions is not an artistic failure, but a brilliant artistic statement of audience expectation management. Burt lauds Swift for her “deep attachment to the verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge conventions of modern songwriting.” This is true: Swift is quite dedicated to specific patterns from recent hits. Many, many musical artists have used the I V vi IV chord progression: Better than Ezra’s “Good,” Justin Bieber’s “Baby,” and Rebecca Black’s “Friday.” Maybe some of these artists even wrote one additional song repeating the same chord pattern. Swift, in her dedication, has actively chosen to deploy the same recognizable chord sequence 21 times. (And she’s used the alternatively famous IV I V vi and vi IV I V progressions at least 9 times each.)

[…]

Swift’s genius status also demonstrates how little tension remains between art and business. In my new book Blank Space, I discuss the rise of what I call entrepreneurial heroism: “the glorification of business savvy as equivalent to artistic genius.” Avant-garde artists never made billions, because ostranie is a bad strategy for securing extraordinary profit or maximizing shareholder value. But when genius is simply “clever deployment of the thing everyone already wants,” there is no longer an inherent conflict with business logic.

Source: Culture: An Owner’s Manual

Image: Rosa Rafael

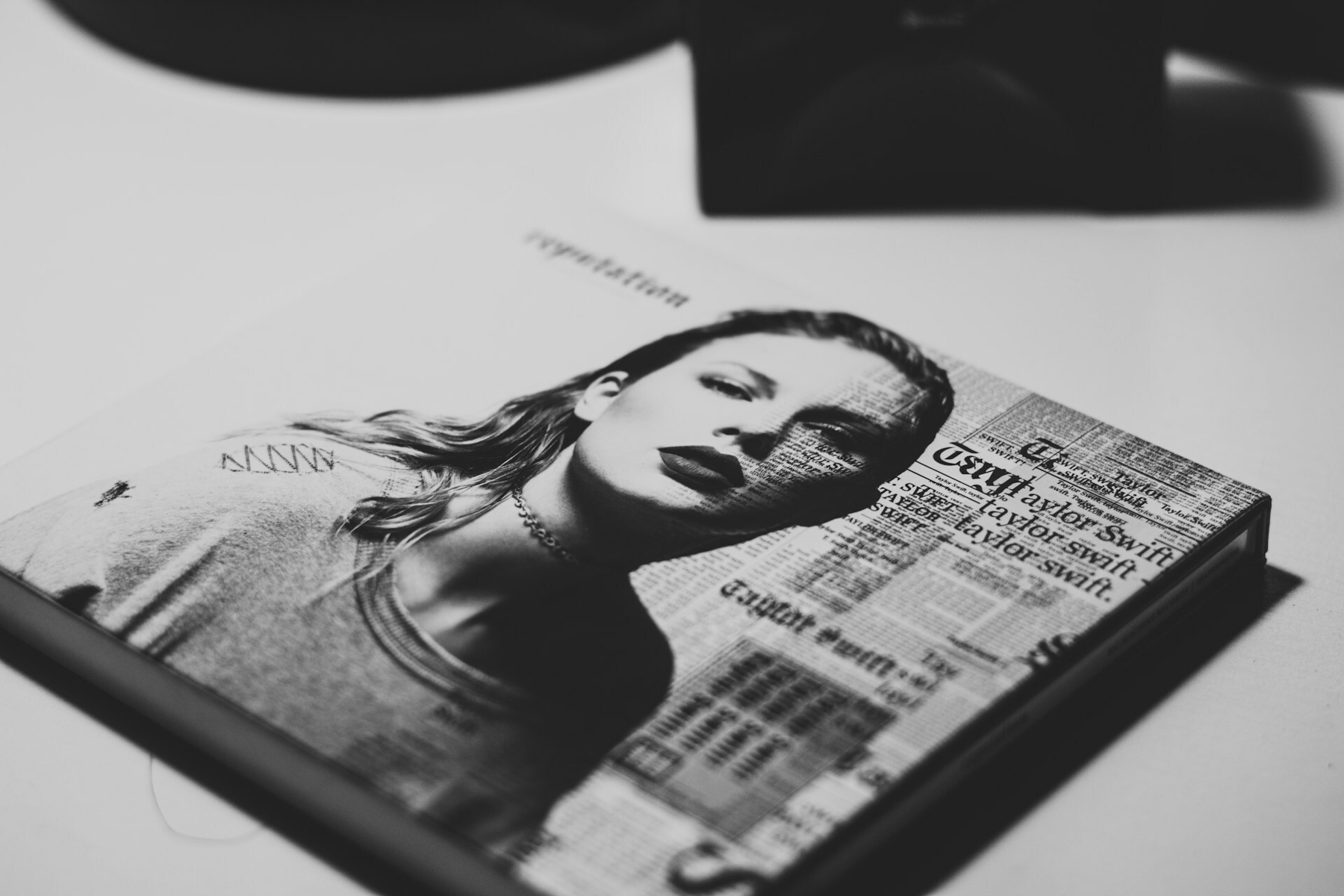

For every snarky comment, there are 10x as many people admiring your work

I’ve talked many times about “increasing your serendipity surface” and you can hear me discussing the idea on this podcast episode from 2024. In this post, Aaron Francis breaks things down into ‘doing the work’, ‘hitting the publish button’, and ‘capturing the luck.’

It’s a useful post, although I don’t think Francis talks enough about the network/community aspect and being part of something bigger than yourself. It’s not all about the personal brand! That’s why I prefer the term ‘serendipity’ to luck ‘luck’ — for me, I’m more interested in the connections than the career advancement opportunities. Although they often go hand-in-hand.

No matter how hard you work, it still takes a little bit of luck for something to hit. That can be discouraging, since luck feels like a force outside our control. But the good news is that we can increase our chances of encountering good luck. That may sound like magic, but it’s not supernatural. The trick is to increase the number of opportunities we have for good fortune to find us. The simple act of publishing your work is one of the best ways to invite a little more luck into your life.

[…]

How can we increase the odds of finding luck? By being a person who works in public. By doing work and being public about it, you build a reputation for yourself. You build a track record. You build a public body of work that speaks on your behalf better than any resume ever could.

[…]

Sharing things you’re learning or making is not prideful. People are drawn to other people in motion. People want to follow along, people want to learn things, people want to be a part of your journey. It’s not bragging to say, “I’ve made a thing and I think it’s cool!” Bringing people along is a good thing for everyone. By publishing your work you’re helping people learn. You’re inspiring others to create.

[…]

Publishing is a skill, it’s something you can learn. You’ll need to build your publishing skill just like you built every other skill you have.

Don’t be afraid to publish along the way. You don’t have to wait until you’re done to drop a perfect, finished artifact from the sky (in fact, you may use that as an excuse to never publish). People like stories, so use that to your benefit. Share the wins, the losses, and the thought processes. Bring us along! If you haven’t been in the habit of sharing your work, it’s going to feel weird when you start. That’s normal! Keep going, you get used to it.

[…]

The formula may be simple, but I’ll admit it’s not always easy. It’s scary to put yourself out there. It’s hard to open yourself up to criticism. People online can be mean. But for every snarky comment, there are ten times as many people quietly following along and admiring not only your work, but your bravery to put it out publicly. And at some point, one of those people quietly following along will reach out with a life-changing opportunity and you’ll think, “Wow, that was lucky.”

Source: The ReadME Project

Image: CC BY-NC-ND Visual Thinkery

The same tools that are keeping some people connected to reality are blurring the lines of what is real for others

I haven’t included the anecdotes cited by Charlie Warzel in his article for The Atlantic but they’re worth a read. It’s not just kids who spend a lot of time on their devices, but increasingly older people too.

As ever, people are quick to rush to moral judgement, and I’m sure there are plenty of problematic cases of people prioritising scrolling over socialising. However, life is different post-pandemic, and sometimes we judge others in ways we wouldn’t want them to judge us.

Screen-time panics typically position children as being without agency, completely at the mercy of evil tech companies that adults must intervene to defend against. But a version of the problem exists on the opposite side of the age spectrum, too: instead of a phone-based childhood, a phone-based retirement.

[…]

Older people really are spending more time online, according to various research, and their usage has been moving in that direction for years. In 2019, the Pew Research Center found that people 60 and older “now spend more than half of their daily leisure time, four hours and 16 minutes, in front of screens,” many watching online videos. A lot of this seems to be happening on YouTube: This year, Nielsen reported that adults 65 and up now watch YouTube on their TVs nearly twice as much as they did two years ago. A recent survey of Americans over 50 revealed that “the average respondent spends a collective 22 hours per week in front of some type of screen.” And one 2,000-person survey of adults aged 59 to 77 showed that 40 percent of respondents felt “anxious or uncomfortable without access” to their device.

[…]

The thing to remember is that not all screen use is equal, especially among older people. Some research suggests that spending time on devices may be linked to better cognitive function for people over 50. Word games, information sleuthing, instructional videos, and even just chatting with friends can provide positive stimuli. Vahia suggests that online habits that might be concerning for young or middle-aged people ought to be considered differently for older generations. “High technology use in teenagers and adolescents is often associated with worse mental health and is a predictor of sort of more isolation and loneliness, even depression,” he told me. “Whereas in older adults, engaging in technology seems to be protecting them from isolation and loneliness.”

[…]

This is a muddled mess. The same tools that are keeping some people connected to reality are blurring the lines of what is real for others. But rather than rush to judgment, younger people should use their concern to open up a conversation—to put down the phones and talk.

Source: The Atlantic

Image: Frankie Cordoba

The world is rarely as neat as any scenario

The TL;DR of this lengthy post by Tim O’Reilly and Mike Loukides is that, as ever, the likelihood is that AI is somewhere between “something we’ve seen before” (i.e. normal technology) and “something completely different” (i.e. the singularity).

In other words, it is likely to be a gamechanger, but probably not in the way that is currently envisaged. One example of this is the way that the energy demands are likely to help us transition to renewables more quickly. It’s also likely to help revolutionise some industries quickly, but take decades to filter into others. The world is a complicated place.

At O’Reilly, we don’t believe in predicting the future. But we do believe you can see signs of the future in the present. Every day, news items land, and if you read them with a kind of soft focus, they slowly add up. Trends are vectors with both a magnitude and a direction, and by watching a series of data points light up those vectors, you can see possible futures taking shape.

[…]

For AI in 2026 and beyond, we see two fundamentally different scenarios that have been competing for attention. Nearly every debate about AI, whether about jobs, about investment, about regulation, or about the shape of the economy to come, is really an argument about which of these scenarios is correct.

Scenario one: AGI is an economic singularity. AI boosters are already backing away from predictions of imminent superintelligent AI leading to a complete break with all human history, but they still envision a fast takeoff of systems capable enough to perform most cognitive work that humans do today. Not perfectly, perhaps, and not in every domain immediately, but well enough, and improving fast enough, that the economic and social consequences will be transformative within this decade. We might call this the economic singularity (to distinguish it from the more complete singularity envisioned by thinkers from John von Neumann, I. J. Good, and Vernor Vinge to Ray Kurzweil).

In this possible future, we aren’t experiencing an ordinary technology cycle. We are experiencing the start of a civilization-level discontinuity. The nature of work changes fundamentally. The question is not which jobs AI will take but which jobs it won’t. Capital’s share of economic output rises dramatically; labor’s share falls. The companies and countries that master this technology first will gain advantages that compound rapidly.

[…]

Scenario two: AI is a normal technology. In this scenario, articulated most clearly by Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor of Princeton, AI is a powerful and important technology but nonetheless subject to all the normal dynamics of adoption, integration, and diminishing returns. Even if we develop true AGI, adoption will still be a slow process. Like previous waves of automation, it will transform some industries, augment many workers, displace some, but most importantly, take decades to fully diffuse through the economy.

In this world, AI faces the same barriers that every enterprise technology faces: integration costs, organizational resistance, regulatory friction, security concerns, training requirements, and the stubborn complexity of real-world workflows. Impressive demos don’t translate smoothly into deployed systems. The ROI is real but incremental. The hype cycle does what hype cycles do: Expectations crash before realistic adoption begins.

[…]

Every transformative infrastructure build-out begins with a bubble. The railroads of the 1840s, the electrical grid of the 1900s, the fiber-optic networks of the 1990s all involved speculative excess, but all left behind infrastructure that powered decades of subsequent growth. One question is whether AI infrastructure is like the dot-com bubble (which left behind useful fiber and data centers) or the housing bubble (which left behind empty subdivisions and a financial crisis).

The real question when faced with a bubble is What will be the source of value in what is left? It most likely won’t be in the AI chips, which have a short useful life. It may not even be in the data centers themselves. It may be in a new approach to programming that unlocks entirely new classes of applications. But one pretty good bet is that there will be enduring value in the energy infrastructure build-out. Given the Trump administration’s war on renewable energy, the market demand for energy in the AI build-out may be its saving grace. A future of abundant, cheap energy rather than the current fight for access that drives up prices for consumers could be a very nice outcome.

[…]

The most likely outcome, even restricted to these two hypothetical scenarios, is something in between. AI may achieve something like AGI for coding, text, and video while remaining a normal technology for embodied tasks and complex reasoning. It may transform some industries rapidly while others resist for decades. The world is rarely as neat as any scenario.

Source: O’Reilly Radar

Image: Nahrizul Kadri

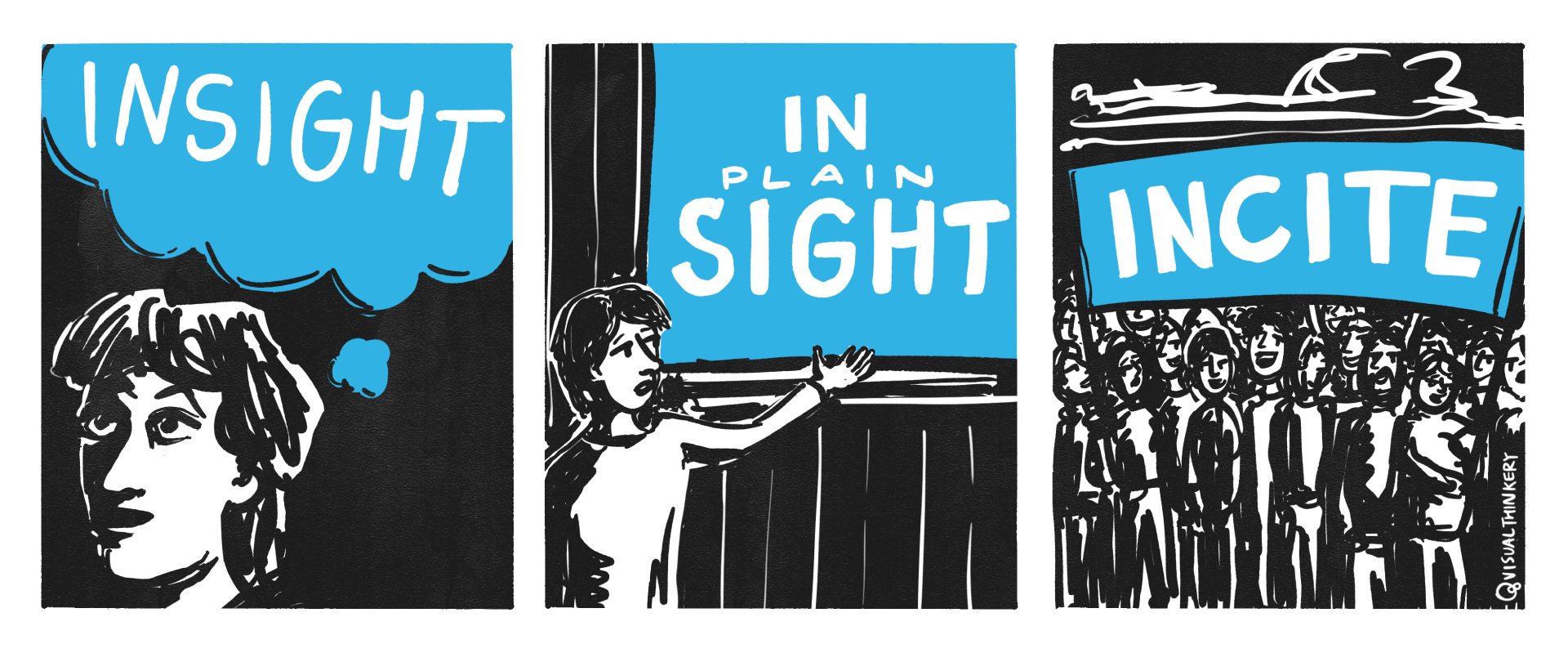

Choose your own inspirational adventure

I’d never thought of it like this, but essentially there are four genres of motivational advice. They all contradict each other, showing the context-dependency of such things.

Source: Are.na

…and we’re back! A quick reminder that you can support Thought Shrapnel with a one-off or monthly donation. Thanks!

Best of Thought Shrapnel 2025

👋 A really quick one to say that I’ve shared my favourite Thought Shrapnel posts of 2025 here:

blog.dougbelshaw.com/favourite…

Regular readers of my personal blog may notice that the above web address is slightly different, as I’ve moved from WordPress to Ghost.

If that doesn’t mean anything to you, don’t worry! There’s no need to change anything to continue receiving the Thought Shrapnel digest every Sunday.

However, if you’re interested in (re-)subscribing to my personal blog, you’ll need to click through and press some buttons!

— Doug

Thought Shrapnel will return in 2026.

On AI leisuretime 'dependence'

It’s not that surprising to me that people would use LLMs in their everyday screen-mediated interactions. In general, people want to appear “normal” and impress other people. Life is ambiguous, mostly unproductively so, meaning that any help in navigating that is likely to be welcome.

Having a seemingly-sentient interlocutor available to run ideas past seems like a good idea, until you realise that it doesn’t really have much clue about the context of human relationships. Generic advice is generic.

For other things, though, it can be super-useful. For example, we recently had some roofers round who encouraged us to spend £thousands replacing our roof, until Perplexity pointed out that our recent heat pump installation probably meant that the ‘leak’ might actually be condensation..

Just as the word clanker now serves as a slur for chatbots and agentic AI, a new lexicon — including secondhand thinkers, ChatNPC, sloppers, and botlickers — is being workshopped by people online to describe the kind of ChatGPT user who seems hopelessly dependent on the mediocre platform. Online, people aren’t mincing words when it comes to expressing their disdain for and irritation with “those types of people,” as Betty describes them. Escape-room employees have crowded around several viral tweets and TikToks to share stories of ChatGPT’s invasion. “So many groups of teens try to sneakily pull out their phones and ask ChatGPT how to grasp the concept of puzzles, then get mad when I tell them to use their brains and the actual person who can help them,” reads one comment. On X, same energy: “Using ChatGPT to aid you through an escape room is bonkers bozo loser killjoy dumdum shitass insanity.”

[…]

The latest and most comprehensive study in ChatGPT usage, published by OpenAI and the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that nonwork messages make up approximately 70 percent of all consumer messages. The study’s “privacy-preserving analysis of 1.5 million conversations” also found that most users value ChatGPT “as an adviser,” like a pocket librarian and portable therapist, as opposed to an assistant. Despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that ChatGPT does not consistently deliver reliable facts, people now seem more likely to use it to come up with recipes, write personal messages, and figure out what to stream than to consult it in higher-stakes situations involving work and money.

[…]

AI technologies initially elbowed their way into all the obvious places — customer service, e-commerce, productivity software — to unsatisfying results. Earlier this year, findings from MIT Media Lab’s Project NANDA said that 95 percent of the companies that invested in generative AI to boost earnings and productivity have zero gains to show for it. Turns out that AI is very bad at most jobs, and this pivot to leisure is likely indicative of the industry’s mounting desperation: Any hope of an “Intelligence Age” that would see the cure for cancer and the end of climate change is seeming less likely, given AI’s toll on the environment. And now that it has failed to “outperform humans at most economically valuable work,” contrary to the hopes of the OpenAI Charter back in 2018, these companies are happy to settle for making us dependent on the products in our leisure time.

Source: The Cut

Image: Michal Šára

Developing a personal brand may leave you emotionally hollow

In this article, Nuar Alsadir examines how psychoanalysis can help people move from living out “inherited” roles and unexamined patterns towards making choices that feel more alive, truthful, and — perhaps, most importantly — internally grounded. This is centred on the idea of a “true self” which is contrasted with the ways social pressures, family expectations, and cultural scripts shape what we think we want.

Alsadir draws on thinkers such as Winnicott, Žižek, and Baudrillard, showing how identity can be reduced to performance or brand, and argues that paying attention to so-called “slips,” jokes, and other unplanned eruptions of the psyche can be revealing. I particularly appreciated the passage below, in which she explores what happens when a person’s carefully managed public image hardens into a kind of “performance” that replaces their inner life. A self built on external “consistency” and “strategic signalling” risks becoming technically convincing yet emotionally hollow, like an actor whose performance is polished but lacks genuine life.

Some people refer to the emotions and perceptions they signal about themselves to others as their “brand.” A personal brand is maintained through a set of consistent choices that signify corresponding character traits—an approach that shows how an essentialist idea of identity can be manipulated for strategic purposes even as it blocks out information from the external world and calcifies habitual patterns of behavior.

Focusing on the surface, lining up your external chips, often results in immediate social reward, yet it can also cause you to lose sight of your interior. In extreme cases, the surface may even become the interior, like the map that comes to stand in for the territory, as philosopher Jean Baudrillard describes it: a simulation that takes the place of the real. The virtual can even feel more real than the real, as happened to a couple in Korea who left their infant daughter at home while they camped out in an internet café playing a video game in which they successfully raised a virtual child. Their daughter starved to death.

When a person becomes a simulation—when it is difficult to distinguish between their self and their role in the game—they may be said, in psychoanalytic terms, to have an “as-if” personality. An as-if person, according to psychoanalyst Helen Deutsch, who coined the term, appears “intellectually intact,” able to create a “repetition of a prototype [but] without the slightest trace of originality” because “expressions of emotion are formal . . . all inner experience is completely excluded.” She likens the behavior of someone with an as-if personality to “the performance of an actor who is technically well trained but who lacks the necessary spark to make his impersonations true to life”

Source: The Yale Review

Image: PaaZ PG

AI has a 3,000-year history

In this article from the ever-fascinating e-flux Journal, Matteo Pasquinelli article traces AI back to ancient practices involving, he argues, rituals and spatial arrangements as early forms of algorithms.

Pasquinelli points out that Vedic fire rituals (with precisely arranged bricks) is an example of early societies using counting, geometry, and organised spaces to encode knowledge and social order. He explains that algorithms emerged from these physical, ritual actions rather than — as we may have assumed — purely abstract mathematics.

What I like about this article is the way he links this to the way space and power interconnect. Sorting and mapping people and land is a form of computation with social consequences. So modern AI, and in particular neural networks, continues and extends the age-old practice of using encoded rules embedded in physical and social environments.

AI infrastructure is an embodiment of the existing social order and control and, as such, reminds us that algorithms are not neutral but rather deeply political and spatial systems rooted in history.

What people call “AI” is actually a long historical process of crystallizing collective behavior, personal data, and individual labor into privatized algorithms that are used for the automation of complex tasks: from driving to translation, from object recognition to music composition. Just as much as the machines of the industrial age grew out of experimentation, know-how, and the labor of skilled workers, engineers, and craftsmen, the statistical models of AI grow out of the data produced by collective intelligence. Which is to say that AI emerges as an enormous imitation engine of collective intelligence. What is the relation between artificial intelligence and human intelligence? It is the social division of labor.

Source & image: e-flux Journal

Adolescence lasts longer than we thought

This finding makes a lot of intuitive sense to me, and means that my wife and I had our children while we were still adolescents ourselves!

The brain goes through five distinct phases in life, with key turning points at ages nine, 32, 66 and 83, scientists have revealed.

Around 4,000 people up to the age of 90 had scans to reveal the connections between their brain cells.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge showed that the brain stays in the adolescent phase until our early thirties when we “peak”.

They say the results could help us understand why the risk of mental health disorders and dementia varies through life.

The brain is constantly changing in response to new knowledge and experience – but the research shows this is not one smooth pattern from birth to death.

Instead, these are the five brain phases:

- Childhood - from birth to age nine

- Adolescence - from nine to 32

- Adulthood - from 32 to 66

- Early ageing - from 66 to 83

- Late ageing - from 83 onwards

[…]

Unsurprisingly adolescence starts around the onset of puberty, but this is the latest evidence suggesting it ends much later than we assumed. It was once thought to be confined to the teenage years, before neuroscience suggested it continued into your 20s and now early 30s.

This phase is the brain’s only period when its network of neurons gets more efficient. Dr Mousely said this backs up many measures of brain function suggesting it peaks in your early thirties, but added it was “very interesting” that the brain stays in the same phase between nine and 32.

[…]

The study did not look at men and women separately, but there will be questions such as the impact of menopause.

Source: BBC News

Image: Wiki Sinaloa

You'll not catch me using an 'AI browser' any time soon

I use Perplexity on a regular basis, and am paying for the ‘Pro’ version. It constantly nags me to download their ‘Comet’ web browser, and even this morning I received an email telling me that Comet is now available for Android.

Not only would I not use an AI browser for privacy reasons (it can read and write to any website you visit) but I wouldn’t use it for security reasons. This example shows why: the simplest ‘attack’ — in this case, literally appending text after a hashtag in the url — can lead to user data being exfiltrated.

What’s perhaps even more concerning is that, having been alerted to this, Google thinks it’s “expected behaviour”? Avoid.

Cato describes HashJack as “the first known indirect prompt injection that can weaponize any legitimate website to manipulate AI browser assistants.” It outlines a method where actors sneak malicious instructions into the fragment part of legitimate URLs, which are then processed by AI browser assistants such as Copilot in Edge, Gemini in Chrome, and Comet from Perplexity AI. Because URL fragments never leave the AI browser, traditional network and server defenses cannot see them, turning legitimate websites into attack vectors.

The new technique works by appending a “#” to the end of a normal URL, which doesn’t change its destination, then adding malicious instructions after that symbol. When a user interacts with a page via their AI browser assistant, those instructions feed into the large language model and can trigger outcomes like data exfiltration, phishing, misinformation, malware guidance, or even medical harm – providing users with information such as incorrect dosage guidance.

“This discovery is especially dangerous because it weaponizes legitimate websites through their URLs. Users see a trusted site, trust their AI browser, and in turn trust the AI assistant’s output – making the likelihood of success far higher than with traditional phishing,” said Vitaly Simonovich, a researcher at Cato Networks.

In testing, Cato CTRL (Cato’s threat research arm) found that agent-capable AI browsers like Comet could be commanded to send user data to attacker-controlled endpoints, while more passive assistants could still display misleading instructions or malicious links. It’s a significant departure from typical “direct” prompt injections, because users think they’re only interacting with a trusted page, even as hidden fragments feed attacker links or trigger background calls.

Cato’s disclosure timeline shows that Google and Microsoft were alerted to HashJack in August, while the findings were flagged with Perplexity in July. Google classified it as “won’t fix (intended behavior)” and low severity, while Perplexity and Microsoft applied fixes to their respective AI browsers.

Source: The Register

Image: Immo Wegman

The caffeination roller coaster

Author, academic, and regular Thought Shrapnel reader Bryan Alexander used to drink a lot of caffeine. And I mean a lot. A post of his resurfaced on Hacker News recently about how he went cold turkey back in 2011 for health reasons. I let him know about this, and he said he’d write an update.

The excerpt below is taken from that update. I have to say that, although I’ve never been a huge coffee drinker, coming off it entirely this year as part of my experiments and investigations into my medical condition has shown that I’m actually better off without it. If you’re in a position where you’re in control of your calendar and schedule, perhaps it’s just not necessary?

Readers might be interested to know that my physical health is fine, according to all medical tests. I’m closing in on 60 years old and all indicators are good. It helps that I am very physically active, between walking a lot, biking regularly, and lifting weights every two days. I’m very professionally active, with a big research agenda, teaching classes, traveling to give talks, writing books, making videos, creating newsletters, etc. The lack of caffeine in my body hasn’t slowed me down a bit.

Mental changes might be more interesting. For years I’ve felt zero temptation to fall off the wagon, despite having plenty of opportunities. When grocery shopping for the house I see vast amounts of caffeine, from the coffee and tea aisle in shops to many coffee vendors hawking their wares at farmers’ markets to omnipresent soda, yet I simply pass them by. It’s a bit like seeing baby products (baby food, diapers, etc), which I mentally process as part of a previous stage of my life (our children are adults now) and therefore not germane to me presently. Every morning I make coffee for my wife but feel no desire to sip any of it. Back when I went cold turkey I longed for it, then trained myself to associate caffeine with sickness, which worked. Nowadays caffeine just not a factor in my thought or feeling. Thirteen years is a long time.

My days are different. When I was on coffee etc. my daily routine included a major caffeination roller coaster. I woke up groggy and badly needed the jolt (or Jolt). I would lose energy, badly, at certain times of the day or in certain situations (boring meeting, long plane flight) and craved the chemical boost. I fear that as a result I wasn’t just hyper when caffeine worked in my veins, but also impatient with non-overclocking people. I think I had a hard time listening and am very sorry for that.

Source: Bryan Alexander

Image: Sahand Hoseini

Early blogger energy

Elizabeth Spiers wants blogs to be weird again. I think the “early blogger energy” she talks about is potentially either a) weirdly specific to a subset of Xennials, or b) just a euphemism for ‘high agency’.

[P]opular blogs have been commercialized; added comment sections and video; migrated to social media platforms; and been subsumed by large media companies. The growth of social media in particular has wiped out a particular kind of blogging that I sometimes miss: a text-based dialogue between bloggers that required more thought and care than dashing off 180 or 240 characters and calling it a day. In order to participate in the dialogue, you had to invest some effort in what media professionals now call “building an audience” and you couldn’t do that simply by shitposting or responding in facile ways to real arguments.

[…]

[I]f you wanted people to read your blog, you had to make it compelling enough that they would visit it, directly, because they wanted to. And if they wanted to respond to you, they had to do it on their own blog, and link back. The effect of this was that there were few equivalents of the worst aspects of social media that broke through. If someone wanted to troll you, they’d have to do it on their own site and hope you took the bait because otherwise no one would see it.

I think of this now as the difference between living in a house you built that requires some effort to visit and going into a town square where there are not particularly rigorous laws about whether or not someone can punch you in the face. Before social media, if someone wanted to engage with you, they had to come to your house and be civil before you’d give them the time of day or let them in. And if they wanted you to engage with them, they’d have to make their own house compelling enough that you’d want to visit.

[…]

Early blogging was slower, less beholden to the hourly news cycle, and people were more inclined to talk about personal enthusiasms as well as what was going on in the world because blogs were considered an individual enterprise, not necessarily akin to a regular publication. One of my early blogs was mostly about economics, a Ukrainian punk band called Gogol Bordello, politics, and a bar on Canal street that turned into an Eastern European disco every night around midnight.

[…]

Some of the best blogs have evolved and expanded. Independent media is more important than ever, and Donald Trump’s recent attempts to censor mainstream outlets, comedians he doesn’t like, and “leftist” professors underscore the fact that speech is critical. The lesson for me, from the early blogosphere, is that quality of speech matters, too. There’s a part of me that hopes that the most toxic social media platforms will quietly implode because they’re not conducive to it, but that is wishcasting; as long as there are capitalist incentives behind them, they probably won’t. I still look for people with early blogger energy, though — people willing to make an effort to understand the world and engage in a way that isn’t a performance, or trolling, or outright grifting. Enough of them, collectively, can be agents of change.

Source: Talking Points Memo

Image: Michael Dziedzic