These other, really important things intrude on my thinking and distract me

The latest issue of New Philosopher magazine is about ‘choice’ and features a wonderful interview with Barry Schwartz, who is the Darwin Cartwright Emeritus Professor of Social Theory and Social Action at Swarthmore College. He’s the author of The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less which I’ve added to my reading list.

I want to excerpt a couple of parts which I think are particularly insightful. The first is about how he reduced the assessment burden on young people, who he believes suffer from a greater decision burden than previous generations.

Zan Boag: I recall in one of your talks, you mentioned that it came as something of a revelation to you when you realised students simply didn’t have as much time as students in the past.

Barry Schwartz: That was my interpretation.

What I realised, or what I thought, I never gathered data on this in any official way, but when I went to school, so many of the really important decisions we face in life were essentially made for us. People were not plagued by questions of sexual identity, weren’t plagued by questions about what their romantic life should look like. Should I have a girlfriend? The default was yes. Should I get married? The default was yes. When should I get married? Soon as I graduated from college. That was the default, and so on. And so there were still issues like, how do I find the right person?

But it wasn’t the case that every last hour of your daily life was consumed by a need to focus on doing studies without having these other, really important things intrude on my thinking and distract me. Well, this was much less true for my children and it is ever so much less true for my grandchildren.

The second excerpt is the follow-up to the question about how problematic it is to be a ‘maximizer’ in life. I’d usually use the term ‘perfectionist’ and have certainly had to overcome this tendency in myself, as it just makes one miserable. As Schwartz points out, as you get older, you have to come to terms with the fact that you have chosen certain options instead of others, and to be satisfied with the way things are, rather than how they could have been.

Zan Boag: It makes it particularly difficult with these big life decisions, whether it’s jobs, where we live, or partners, because we’re faced with so much choice. People can always wonder about the life they could have led had they made a different decision – say to pursue writing instead of banking; move to San Francisco instead of Sydney; ballroom dancing over Taekwondo. They’re making choices that then will affect the way they lead their lives. Let’s call this a phantom life, the ‘other’ life. How can people find satisfaction with their choices when there are so many available, and the choices you make will often seem like the incorrect ones? How can they find some sort of satisfaction?

Barry Schwartz: I think in the book that I wrote, which by the way, as I told you in an email, I’m about to start writing a new edition of, I make some suggestions, but I think the truth of the matter is that it is very hard to shut off these enemies of satisfaction in the modern world. What we’re talking about, and what I wrote about, is rich society’s problem.

Most people in the world don’t have the problem that there are too many options. They have the opposite problem. But if you happen to live in a part of the world like you and I do, that is the problem. And we don’t have the tools for shutting it down. I make some suggestions, like limit the number of options you consider. Fine. I’m only going to look at six pairs of jeans. It’s one thing to say it and it is another thing to do it, and it’s still a hard thing to do and not be nagged by the knowledge that there are all these options out there that you didn’t look at.

It’s sort of like just quitting smoking. ‘Yeah, I’ll just quit smoking.’ Nice, easy to say, but really, really hard to do when you suffer at least initially when you quit smoking. And so, I think that you have to be prepared for a fair amount of discomfort and a lot of work to change your approach to making decisions, big ones or small ones.

It’s not a surprise to me that young people are in such bad shape because one of the things that we found is that the younger you are, the more likely you are to be a maximizer in decisions. I think one of the things that you learn as you age is that good enough is almost always good enough. But you don’t see too many 20-year-olds who think that. Experience teaches you that good enough is good enough.

After suffering for a generation or so, you settle into a life where you’re satisfied with good enough results of your decisions. But meanwhile, that’s 20 or 30 years of suffering. And what I think… I don’t know if you’re familiar with this somewhat controversial argument about what social media is doing to the welfare of young people.

Source: New Philsoopher: Choice

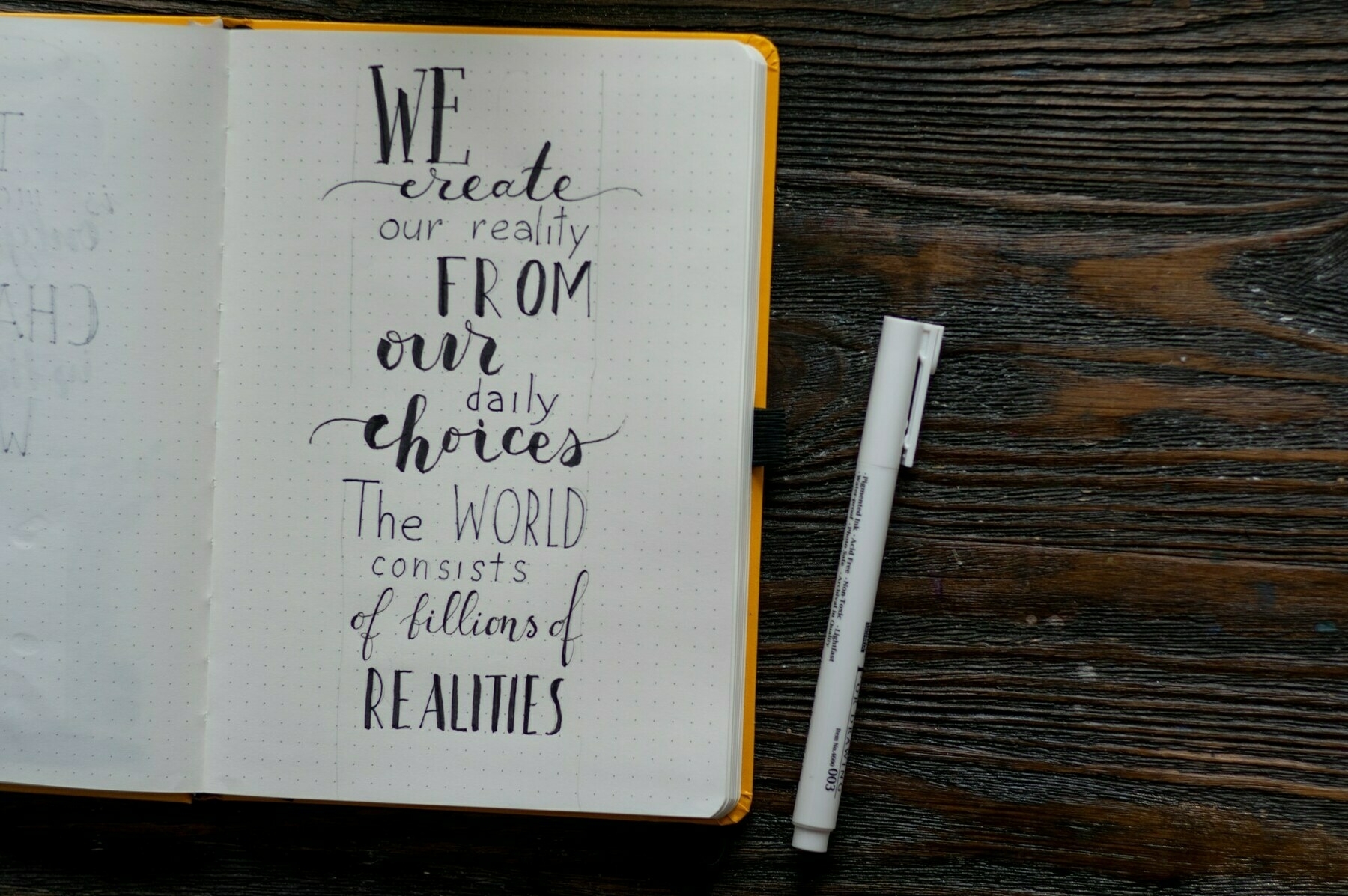

Image: Elena Mozhvilo