It's much easier to go carless if your city has good public transit

I’m a vegetarian who drives an electric vehicle (EV). In a few weeks' time, we’re getting a heat pump installed so that we can remove our gas boiler. These are all climate-positive things to do, and I’m trying to do my bit.

This article by the World Resources Institute shows how important it is that there is an infrastructure that enables individual decision-making to take place. For example, I’ve been vegetarian now for eight years, and it’s much easier to remove meat from your diet these days even than when I started to so in 2017. Likewise, because of investment in EV infrastructure, these days it’s unproblematic to own or lease an EV.

It’s interesting being an early-ish adopter of air source heat pump technology in the UK. The process is not as smooth as it could be, with our driveway having to be dug up to upgrade the total electricity supply capacity entering our property. So, although we have visited a couple of heat pumps and there is a government grant, it’s still more expensive, and involves more upheaval, than just getting another combi boiler.

Coupled with active hostility in some quarters, it’s a good example of how the Overton Window can apply to technology interventions and pro-climate lifestyle choices. That’s why, as well as making such choices ourselves, we should be aware of, and be advocating for, the systems within which those choices can be made easier.

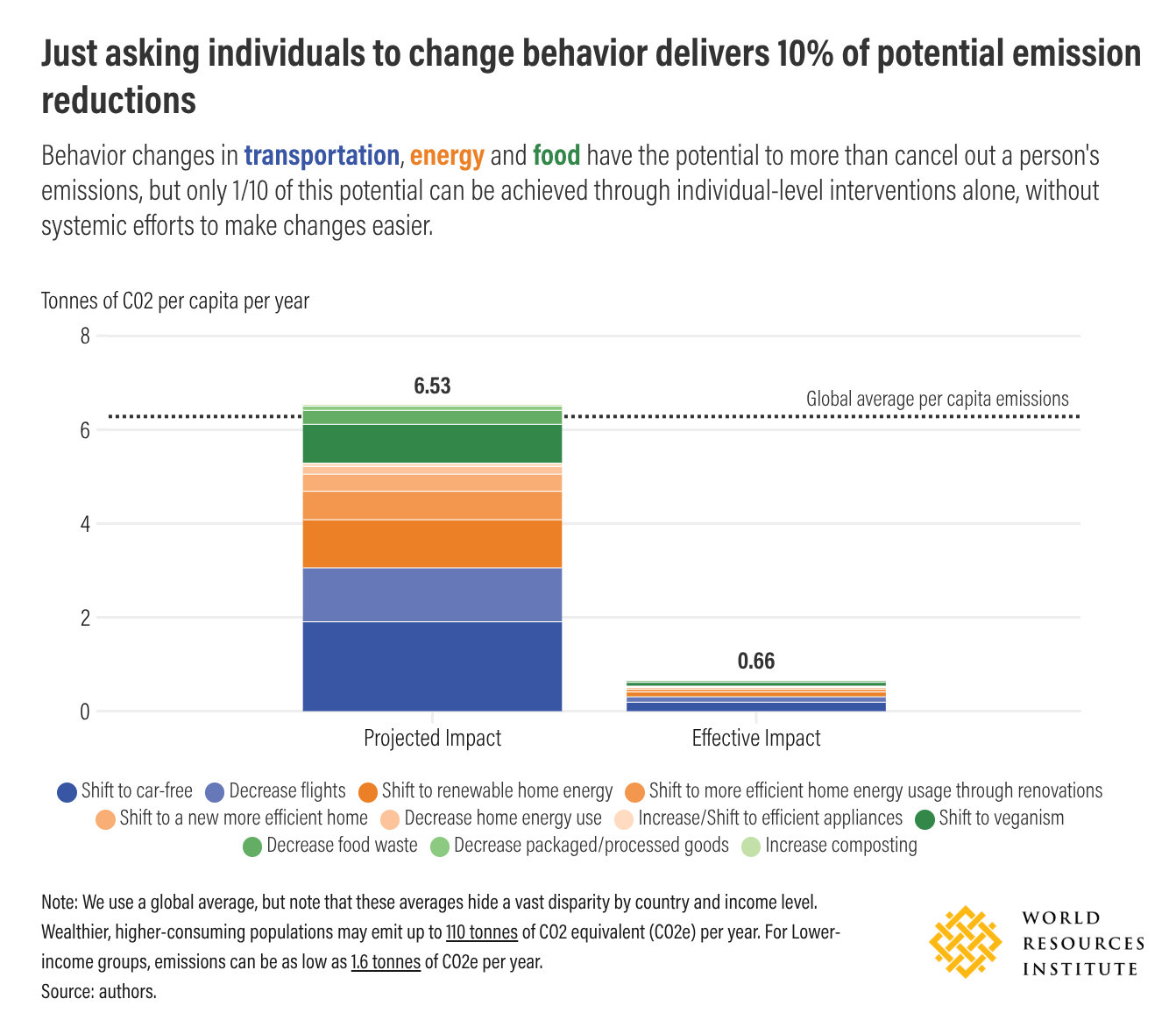

Our data shows that pro-climate behavior changes, such as driving less or eating less meat, could theoretically cancel out all the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions an average person produces each year — specifically among high-income, high-emitting populations.

But it also reveals that efforts focused exclusively on changing behaviors, and not the overarching systems around them, only achieve about one-tenth of this emissions-reduction potential. The remaining 90% stays locked away, dependent on governments, businesses and our own collective action to make sustainable choices more accessible for everyone. (Case in point: It’s much easier to go carless if your city has good public transit.)

[…]

We found that, in theory, shifting to 11 pro-climate behaviors we analyzed in the energy, transport and food sectors could reduce individuals' GHG emissions by about 6.53 tonnes per year. This would more than cancel out what an average person currently emits (about 6.3 tonnes per year). However, our data also shows that when people attempt these changes in the real world, without supportive systems, they typically only reduce emissions by about 0.63 tonnes yearly — just 10% of what’s theoretically possible.

It’s not that individual changes don’t matter; when someone switches to an electric vehicle (EV) or avoids a flight, they make a real impact. The problem is that without supportive infrastructure, policies or incentives (such as public EV chargers or financial subsidies), these programs struggle to drive the broad-based change the world really needs.

Source & image: World Resources Institute

Workers of the future must be emboldened to eschew wages in favour of dropping into the abyss

Note: as regular readers will be aware, my habit is to quote part of the excerpt as the title of Thought Shrapnel posts. I, personally, am not advocating for abyss-directed activity.

I’m not sure who the cipher “aethn” behind this essay is, but this is a pretty standard argument dressed up in fancy (and somewhat eschatological) language. I’ve tried to excerpt the main thrust, which is: LLMs are getting better and seem to be starting to replace some lower level jobs; this will continue and cause a rupture in the fabric of society. Somehow we need to prepare for this.

While I do believe that AI is somewhat qualitatively different from previous technological inventions, I’m also a student of history and so know that disruption doesn’t happen everywhere all at once. As William Gibson is famously quoted as saying, “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.” Just because some people, like the author (and like me), are messing around with LLMs and finding them powerful for our work, doesn’t mean that everyone else is.

Essays like this tend to miss out existing inequality in a rush to talk about future inequalities. And, it has to be said that our western economic and political structures have proven remarkably resilient to a number of shocks over the past centuries. Fredric Jameson noted that, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” I’d note that, sometimes, one person’s “violent revolution” is another person’s evolution of capitalism into a new form.

We are at the precipice of a revolution more violent than the Industrial Revolution. This revolution is not about the typical vulgar parochial anxieties on job security—although it is part of it—it’s about a violent upheaval of the very socio-economic fabric in the way our world is organized.

[…]

The latest innovations go far beyond logarithmic gains: there is now GPT-based software which replaces much of the work of CAD Designers, Illustrators, Video Editors, Electrical Engineers, Software Engineers, Financial Analysts, and Radiologists, to name a few. This radical automation exists without any sophisticated fine tuning or training.

[…]

The frequent naive view of the amount paid in a wage is that it’s proportional to the difficulty of the job. If this were the case then certainly all wages will substantially be decreased with the advent of LLMs and that regular economic structure will be maintained. Instead, through the normal polemics we find that’s not the case.

Wage is instead best viewed from the perspective of the profit maximizing economic agent, as in what motivates such an agent to accept a wage from another party at all. If such an agent were able to endeavor alone and capture all of the value from its enterprise it would do so. […] [T]he agent must determine if an offered wage is greater than the expected value of its solo enterprise. We then find that wage must be greater than the expected value of the opportunity cost of the uncaptured labor value incurred due to employment. For much knowledge based work, this is acute since with the same skills needed for employment one can make a competing enterprise to their employer and capture all the value. Other professions require you to have large capital to do so, so the opportunity cost is either non-existent if you cannot access that capital or further discounted by the financing cost and the risk.

[…]

Generally aligning a team on a common product requires expensive payments to each member to provide contributions. Indeed, the early-stage venture capital industry relies on this fact.

The latest LLMs make such a provision completely redundant. The proprietor of today can supervise and delegate tasks required to build a product to the latest GPTs in virtually any knowledge field. The single proprietor now has the efficacy of maybe a team of 6-10 conservatively and further is able to produce even higher quality work.

[…]

One may demur and claim there simply won’t be enough knowledge-based services in demand, however we instead find a Jevon’s paradox, where demand for these services increases. The reduction in costs of producing the same services will make them more ubiquitous and bespoke at even a per individual basis.

[…]

Corporations whose products have no moat by economic scale or network will be forced into specializing their products as they surrender market share to the sea of companies. In the Deleuzian fashion, proprietors can build almost as quickly as they can imagine, as predicted, rattling the foundations of the economic order itself.

[…]

The social order must change drastically to a future where institutions are no longer designed to feed corporations future employees, they merely won’t harbor that demand. Many existing knowledge based workers will largely have no choice but to engage in enterprise. Educational systems must adapt and accommodate this new entrepreneurial exigency for labor in the new economic order. Workers of the future must be emboldened to eschew wages in favor of dropping into the abyss in order to have any meaningful income.

Source: aethn’s essays

Image: Maksym Mazur

I have to acknowledge and accept the fact that I use tools built by awful people to create beautiful things.

As the author of this article, Ankur Sethi, ponders, why is it that as people interested in technology we often don’t hold the rest of our consumption and use to the same standards as the digital world? Do we change where we buy our clothes and choose which car we drive based on similar ethical standards to those we use when we select our operating systems and digital platforms?

It’s a reminder, I guess, that there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism. But I, for one, can still try.

We’ve structured our society so that the best products and services are made by the worst people in the world. Of course you can deliver packages earlier than everyone else if you overwork your employees. Of course you can sell the fastest computers at the cheapest prices if you keep moving your manufacturing operations to countries with the worst labor and environmental laws. Of course you can build the smartest AI models if you slurp up everybody else’s intellectual property without asking for consent first.

It makes little difference to how tech businesses operate when a smattering of concerned individuals opt out of using their products and services. Things will only change when democratically elected governments across the world step in with regulation, drag Big Tech through the courts, and fine them billions of dollars.

Things will only change when being an asshole stops being a competitive advantage.

Until that day arrives, I have to learn to live in a state of tension with my tools. I have to acknowledge and accept the fact that I use tools built by awful people to create beautiful things.

Source: Ankur Sethi

Image: Sigmund

The problem is not just that the Gmail team wrote a bad system prompt. The problem is that I'm not allowed to change it.

I’ve often used the metaphor of the ‘horseless carriage’ in my work around new literacies, making the McLuhan-esque point that people tend to use existing mental models of technology to understand new forms. So, for example, if you remember the original iPad, there were plenty of ‘skeuomorphic’ touches, such as ebooks having fake pages either side of the ones you’re reading.

This article talks about generative AI, and in particular Google’s choices when it comes to how they’ve chosen to integrate it into GMail. The author, Pete Koomen, includes some lovely little interactive elements showing the differences between how Gemini (Google AI model) performs things by default, and how he would like it to behave.

The System Prompt explains to the model how to accomplish a particular set of tasks, and is re-used over and over again. The User Prompt describes a specific task to be done.

[…]

The problem is not just that the Gmail team wrote a bad system prompt. The problem is that I’m not allowed to change it.

[…]

As of April 2025 most AI still apps don’t (intentionally) expose their system prompts. Why not?

Here’s the insight, and the reason why I enjoy ‘vibe coding’ so much (i.e. creating web apps using a conversational interface):

The modern software industry is built on the assumption that we need developers to act as middlemen between us and computers. They translate our desires into code and abstract it away from us behind simple, one-size-fits-all interfaces we can understand.

The division of labor is clear: developers decide how software behaves in the general case, and users provide input that determines how it behaves in the specific case.

By splitting the prompt into System and User components, we’ve created analogs that map cleanly onto these old world domains. The System Prompt governs how the LLM behaves in the general case and the User Prompt is the input that determines how the LLM behaves in the specific case.

With this framing, it’s only natural to assume that it’s the developer’s job to write the System Prompt and the user’s job to write the User Prompt. That’s how we’ve always built software.

But in Gmail’s case, this AI assistant is supposed to represent me. These are my emails and I want them written in my voice, not the one-size-fits-all voice designed by a committee of Google product managers and lawyers.

In the old world I’d have to accept the one-size-fits-all version because the only alternative was to write my own program, and writing programs is hard.

In the new world I don’t need a middleman tell a computer what to do anymore. I just need to be able to write my own System Prompt, and writing System Prompts is easy!

Source: Pete Koomen

Image: Alan Warburton

How times change

Earlier this week, I had the pleasure of attending the Lit & Phil in Newcastle with my mother where we spent an evening with David Haldane, world-renowned cartoonist. He’s just started a new gig (at the age of 70!) for The Observer.

He outlined how technology had changed over the years: at the start his cartoons would be driven to the train station by his wife, taken on the last train to London, where it would then be taken by courier to the offices of the newspaper or magazine. Then, when fax machines came in, you weren’t sure that what you were sending would actually go to the right place, so sometimes people would be looking all around the place for things he’d sent through.

Much more recently, he mentioned how, with a cut-off date of 21:30, he’d been asked 10 minutes beforehand to redo a cartoon. He obliged, sent it through digitally — and by the time he’d tidied up his stuff and gone downstairs, there was his cartoon on the front page of the “tomorrow’s newspaper front pages” section of the TV news!

How times change.

Participants remembered fake headlines more than real ones regardless of the political concordance of the news story

You Are Not So Smart (YANSS) is a great podcast, and one of the recent episodes is right up my street. Based around this paper by disinformation researchers, it introduces the notion of _dis_confirmation bias.

Essentially, they did rigorous research in the US which showed that people prefer concordance with their existing belief systems over conformance with truth. I was expecting to hear philosopher W.V. Quine referenced in terms of his metaphor of us having a ‘web of belief’. Those beliefs that are toward the periphery of the web are more easily jettisoned than those nearer the centre, which are core to our identity.

Anyway, it’s a really interesting episode, especially given that most people think the problem is ‘fake news’. That’s half the problem: the other part is getting people to prefer (and share) true news rather than random stuff that happens to cohere with their existing beliefs.

Resistance to truth and susceptibility to falsehood threaten democracies around the globe. The present research assesses the magnitude, manifestations, and predictors of these phenomena, while addressing methodological concerns in past research. We conducted a preregistered study with a split-sample design (discovery sample N = 630, validation sample N = 1,100) of U.S. Census-matched online adults. Proponents and opponents of 2020 U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump were presented with fake and real political headlines ahead of the election. The political concordance of the headlines determined participants’ belief in and intention to share news more than the truth of the headlines. This “concordance-over-truth” bias persisted across education levels, analytic reasoning ability, and partisan groups, with some evidence of a stronger effect among Trump supporters. Resistance to true news was stronger than susceptibility to fake news. The most robust predictors of the bias were participants’ belief in the relative objectivity of their political side, extreme views about Trump, and the extent of their one-sided media consumption. Interestingly, participants stronger in analytic reasoning, measured with the Cognitive Reflection Task, were more accurate in discerning real from fake headlines when accurate conclusions aligned with their ideology. Finally, participants remembered fake headlines more than real ones regardless of the political concordance of the news story. Discussion explores why the concordance-over-truth bias observed in our study is more pronounced than previous research suggests, and examines its causes, consequences, and potential remedies. (PsycInfo Database Record (c) 2024 APA, all rights reserved).

Image: Nijwam Swargiary

These parts would end up in a landfill otherwise

‘Degrowth’ is an idea which makes perfect sense in a resource-limited world. Yet the framing remains problematic and doesn’t seem to chime with the current Overton window.

Degrowth’s main argument is that an infinite expansion of the economy is fundamentally contradictory to the finiteness of material resources on Earth. It argues that economic growth measured by GDP should be abandoned as a policy objective. Policy should instead focus on economic and social metrics such as life expectancy, health, education, housing, and ecologically sustainable work as indicators of both ecosystems and human well-being.

I bring this up because of an article I saw in The Verge about ‘Frankenstein’ laptops being created from salvaged parts in India. Done properly, this is degrowth in action: creating value by repurposing e-waste into functional machines. It reminds me of a scene from Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope where Luke Skywalker’s uncle purchases R2-D2 and C-3PO from the Jawas, who resell scrap, droids, and technology they salvage from the environment and crashed ships.

One of the reasons Trump wants a deal with Ukraine and has threatened both Canada and Greenland is due to access to minerals. In a high-tariff, protectionist world, degrowth helps us resist tyrants and create economies that are not based on endless growth. Sometimes that number has to stop going up and to the right.

Across India, in metro markets from Delhi’s Nehru Place to Mumbai’s Lamington Road, technicians like Prasad are repurposing broken and outdated laptops that many see as junk. These “Frankenstein” machines — hybrids of salvaged parts from multiple brands — are sold to students, gig workers, and small businesses, offering a lifeline to those priced out of India’s growing digital economy.

[…]

Manohar Singh, the owner of the workshop-slash-store where Prasad works, flips open a refurbished laptop while sitting on a rickety stool. The screen flickers to life, displaying a crisp image. He smiles — a sign that another machine has been successfully revived.

“We literally make them out of scrap! We also take in second-hand laptops and e-waste from countries like Dubai and China, fix them up, and sell them at half the price of a new one,” he explains.

“A college student or a freelancer can get a good machine for INR 10,000 [about $110 USD] instead of spending INR 70,000 [about $800 USD] on a brand-new one. For many, that difference means being able to work or study at all.”

[…]

[M]any repair technicians have no choice but to rely on informal supply chains, with markets like Delhi’s Seelampur — India’s largest e-waste hub — becoming a critical way to source spare parts. Seelampur processes approximately 30,000 tonnes (33,069 tons) of e-waste daily, providing employment to nearly 50,000 informal workers who extract valuable materials from it. The market is a chaotic maze of discarded electronics, where workers sift through mountains of broken circuit boards, tangled wires, and cracked screens, searching for usable parts.

Farooq Ahmed, an 18-year-old scrap dealer, has spent the last four years sourcing laptop components for technicians like Prasad. “We find working RAM sticks, motherboards with minor faults, batteries that still hold charge and sell it to different electronic workshops,” he says. “These parts would end up in a landfill otherwise.”

[…]

Despite the dangers, the demand for Frankenstein systems continues to grow. And as India’s digital economy expands, the need for such affordable technology will only increase. Many believe that integrating the repair sector into the formal economy could bring about a win-win situation, reducing e-waste, creating jobs, and making technology more accessible.

Sources: Wikipedia & The Verge

Image: Kilian Seiler

You don't fit in. And that is amazing.

A few months ago, when we had basically no work on, I grumpily applied for some jobs. I had a couple of interviews, one of which turned into some consultancy work. But I didn’t get any of them, which on the one hand isn’t very validating, but on the other is secretly very relieving.

Aristotle said that you can’t make a decision as to whether someone is ‘happy’ until after they have died. You need to see the full arc. The same is true of employment: how it all ends is an important factor as to whether you were ‘successful’ or ‘enjoyed’ it. I’ve only had two jobs that ended well. This is because of the mantra I have tried to instil in our two teenagers: people can only treat you the way you let them. I’m not sucking up to anyone, and I’m not changing the way that I think, work, and organise my time to fit a corporate ‘system’.

Which brings us to Mike Monteiro’s post. You should read the whole thing, as he weaves in recollections about being left-handed, neurodivergence, and his own career. The parts I’ve picked out here reflect some of my own experience over the past 22 years of (what some may call) a career. Courtesy of Dan Sinker, I have a Marginally Employed patch below my monitor to remind me I chose this because this is the way. For me, anyway.

Very early on in my “career” (LOL) I decided I wasn’t drift compatible with working in large organizations. I just didn’t enjoy it. Which isn’t to say that I can’t work with people, there are people I absolutely love working with. […] I didn’t like working in large organizations because the larger an organization is, the more likely it is to have a certain way of doing things. Which kinda makes sense, because if you have thousands of people doing things that are supposed to be interconnected, you kinda want a process that everyone can follow, or there’s complete chaos. (The fact that most organizations attempt to do this and it still results in complete chaos is also interesting, but we’re not tackling that today.) The larger an organization becomes, the more it needs everyone to work and think the same way. That way, if it loses a worker, it’s that much easier to plug in a new worker. And while that way of working might make sense for the organization, it’s important that we also ask ourselves, as workers, if it’s working for us.

[…]

Since large organizations made me miserable, I decided to spend my career in small little studios, which tend to be a bit more supportive and even gravitate more towards people who don’t spin in the same direction. Possibly because they were all started by people who don’t spin in the same direction. Or at the same speed. Or spin at all.

[…]

I try to be really careful about how I dole out advice to people. There is no system. There is no one way. There’s no guarantee that our brains will take us on the same journey. I’ll tell people about my own experience in doing something. I’ll tell you that we need to get from Point A to Point B. I’ll tell you how I’ve gotten there in the past, which you can use as a frame of reference, if that helps you, but then I want your brain to do its thing. Because your brain is mapping out a totally different landscape than mine is, and that is fascinating.

[…]

The world is full of… people who want to sell you Design Thinking™… and people who want to see everything spin the same way. They want order. They want sameness. But the only sameness they want is for you to be as miserable as they are. And they’re all miserable. They hate you because you’re a threat. You see what they don’t. You feel what they can’t. You can smell colors! You can read the stars. You see the connections that they can’t. You can paint something, with your own hands, that they have to fire up Three Mile Island to even attempt. You can change your body into what you need it to be. You can love who you love.

You don’t fit in.

And that is amazing.

Source: [Mike Monteiro’s Good News](buttondown.com/monteiro/…]

Image: Mulyadi

Obvious things are obvious if you think about them

I’m sharing two articles together here because they help reframe a couple of things which are important to me. One is about political opinions and demographics, the other one is about meat-eating.

Let’s start with political opinions. The ‘received wisdom’ that older people are more conservative is based on a survivorship bias:

One of the abiding realities of our political era is a major generational split anchored on the right by disproportionately conservative seniors and on the left by disproportionately progressive millennials and post-millennials. This is often thought of as a perfectly natural, even inevitable, phenomenon: Young people are adventurous, open to new ways of thinking, and not terribly invested in the status quo, while old folks have time-tested views, assets they want to protect, and a growing fear of the unknown and unfamiliar.

[…]

But it is important to note that some generational disjunctions in political behavior are driven by demography. It’s well understood that millennials are significantly more diverse than prior generations. But there is something else driving the relative homogeneity of seniors: Poorer people are often hobbled by chronic illness, and succumb to premature death.

The other issue is around the common belief that prehistoric humans ate mainly meat. Of course, animal bones last a lot longer than plant grains, so just as we don’t have much physical evidence of wooden structures (as opposed to stone ones) we have a lot more bones than grains to base theories on.

A new archaeological study along the Jordan River, just south of northern Israel’s Hula Valley, sheds new light on the diets of early humans and challenges long-standing assumptions about prehistoric eating habits. The research shows that ancient hunter-gatherers relied heavily on plant foods, especially starchy varieties, as a key energy source. Contrary to the popular belief that early hominids primarily consumed animal protein, the findings reveal a varied plant-based diet that included acorns, cereals, legumes, and aquatic plants.

[…]

The research contradicts the prevailing narrative that ancient human diets were primarily based on animal protein, as suggested by the popular “paleo” diet. Many of these diets are based on the interpretation of animal bones found in archaeological sites, with plant-based foods rarely preserved.

Sources: New Yorker Magazine & SciTechDaily

Image: William Felipe Seccon

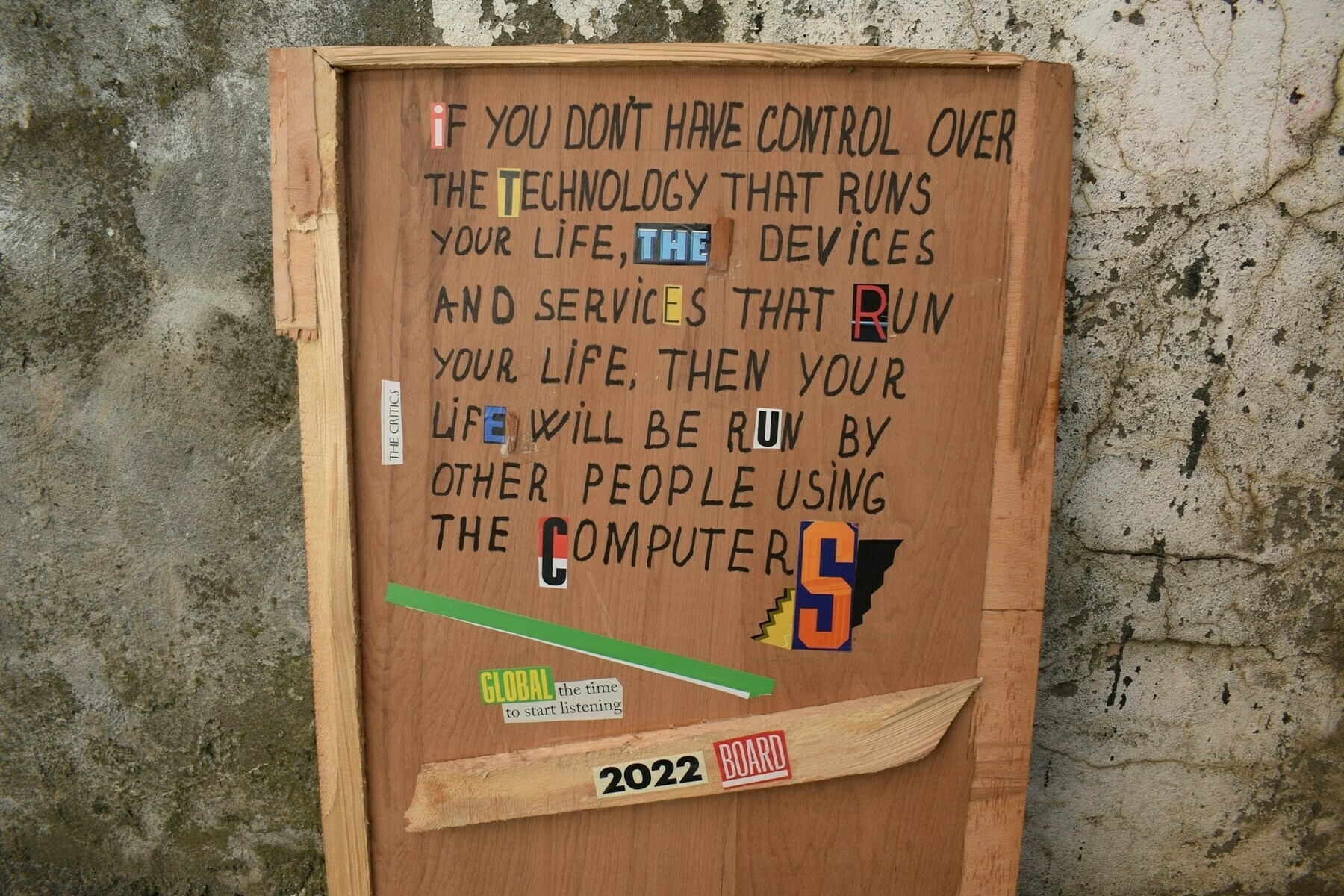

I just think that people who write about technology should have a disclaimer about the tech stack they use

I sent Carole Cadwalladr’s latest TED Talk to people this week who may not otherwise understand what’s going on in the US. Big Tech companies like Google, Meta, and Apple are all in the US, and also… let’s not pretend a similar thing couldn’t happen in other countries. We should be ready.

In this post, Elena Rossini points out how “impossibly incongruous” it is that Cadwalladr uses Bluesky and Substack for her online presence, “two centralized services, owned or funded by questionable groups.”

The products and services we use matter. Not only to protect ourselves, our friends, and our families, but also in terms of resisting a dominant narrative and worldview. I saw that Matt Jukes recently added a colophon to his blog to explain not only his process of writing but the products he uses. I like that.

Carole Cadwalladr has my utmost admiration. The fiery presentation she gave at TED is not diminished by the tech stack she personally uses. I firmly believe everyone should watch her video - it’s digital literacy 101.

Still, I believe that if even Carole Cadwalladr - who recognizes the problem (the broligarchy) and speaks so eloquently against it - is ONLY using American VC-funded Big Tech platforms, her presence there is an implicit endorsement. And her audience will get the indirect message that compromises need to be made and it’s no big deal to use Broligarchs’ platforms because they may be the only solution to get one’s message out there.

[…]

When I learned about the doubling down by Substack founders - who refused to moderate or demonetize newsletters promoting hate speech - I moved away from the platform… and I unsubscribed from 40+ newsletters hosted there (including two paid newsletters). I admire Cadwalladr’s work and I would love to do a paid subscription to her blog - but I won’t as long as she’s on Substack. I am sure there are many people who feel the same way.

[…]

If I were her, I would set up a blog/newsletter on Ghost - with paid membership - and I would keep a Substack account, taking advantage of the Notes feature to share articles hosted on her hypothetical Ghost blog. The best of both worlds.

For social media, I would create an account on the Fediverse and use a tool like Buffer or Fedica to crosspost to multiple accounts.

[…]

I just think that people who write about technology should have a disclaimer about the tech stack they use - in order to see if they’re “walking the talk.” And if people who speak truth to power feel they need to be on VC-backed, centralized, for-profit social networks, sure no problem. But I believe that anyone speaking up against the broligarchy should be active on the Fediverse too - a galaxy of independent, free, open source networks that is not funded by billionaires or crypto bros.

Source: Elena Rossini

Image: Marija Zaric

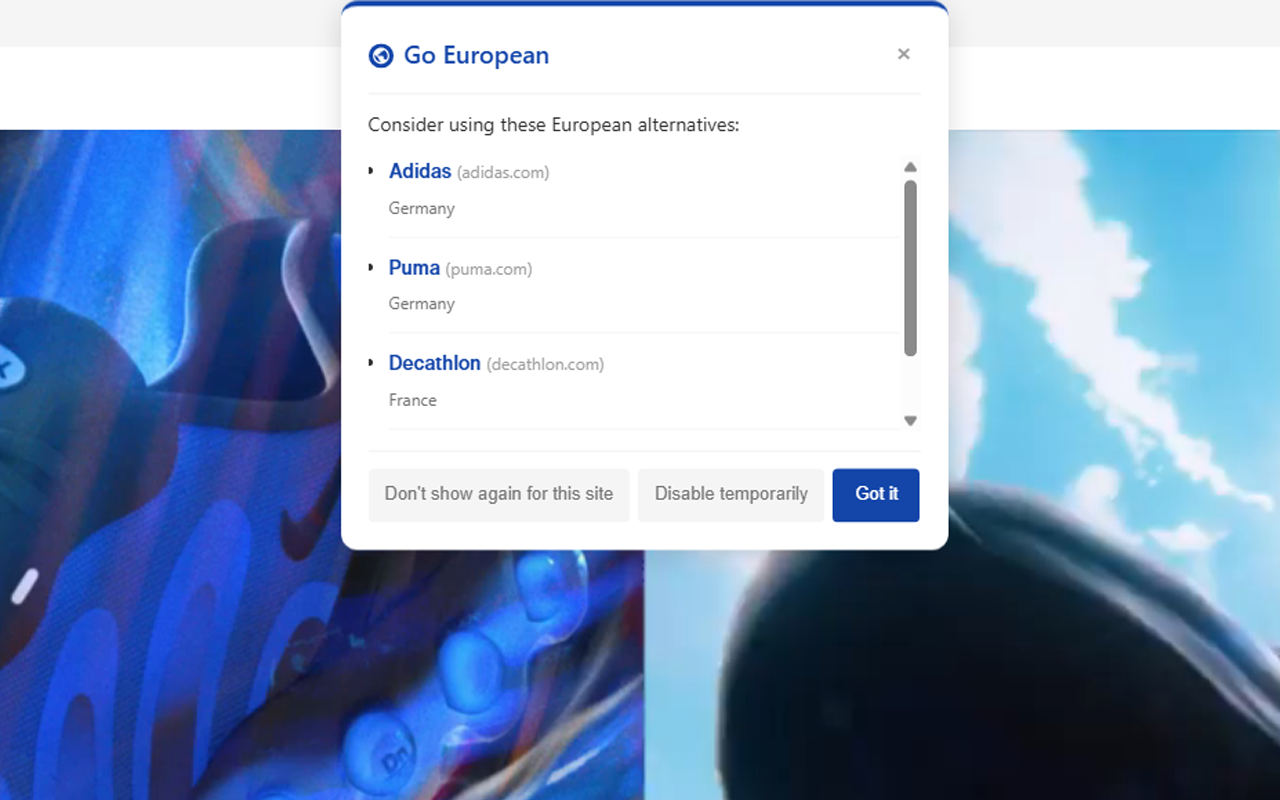

This extension is the solution to becoming more European oriented

There’s a growing movement in the communities of which I’m part to move off US infrastructure and away from US-owned companies. For obvious reasons. This browser extension is a good example of how that is being facilitated, by suggesting European alternatives.

Suggests European website alternatives to non-European websites.

This extension is the solution to becoming more European oriented. The extension provides European alternatives for the most used websites and services around the world wide web.

Key features:

- Site Detection and Notifications

- Automatically recognizes websites that have European alternatives

- Badge counter shows the number of alternatives sites

- Receive unobtrusive notifications about available alternatvies

- Clean, modern UI with information about each alternatives

- One-Click access to visit suggested sites

Source: Go European

Sprint goals suck too

Back in about 2014, I remember Matt Thompson help bring in ‘heartbeats’ to the Mozilla Foundation. As he explained in this post for opensource.com a couple of years later, using that word instead of ‘sprint’ is useful because:

Heartbeats can create a great sense of purpose, and ebb and flow in your team. They can be set to any length—a week, two weeks, a month. It’s really just about bringing people together in a regular, predictable cycle, with a ritual and set of dance steps to ensure everyone’s on the same page, headed in the right direction, and learning and accomplishing important things together.

I was reminded of Matt’s work when I saw Steve Messer’s post about helping a GOV.UK team implement a new model for agile delivery. Similarly, he points out that you don’t need to do two-week sprints.

This is something that Laura and I have been discussing on a project we started last month with a new client. There’s an expectation these days that to work in an ‘agile’ way you have to do sprints. You can use them. But you don’t have to.

Traditional two-week sprints and Scrum provide good training wheels for teams who are new to agile, but those don’t work for well established or high performing teams.

For research and development work (like discovery and alpha), you need a little bit longer to get your head into a domain and have time to play around making scrappy prototypes.

For build work, a two-week sprint isn’t really two weeks. With all the ceremonies required for co-ordination and sharing information – which is a lot more labour-intensive in remote-first settings – you lose a couple of days with two-week sprints.

Sprint goals suck too. It’s far too easy to push it along and limp from fortnight to fortnight, never really considering whether you should stop the workstream. It’s better to think about your appetite for doing something, and then to focus on getting valuable iterations out there rather than committing to a whole thing.

Source: Boring Magic

Image: Matt Collamer

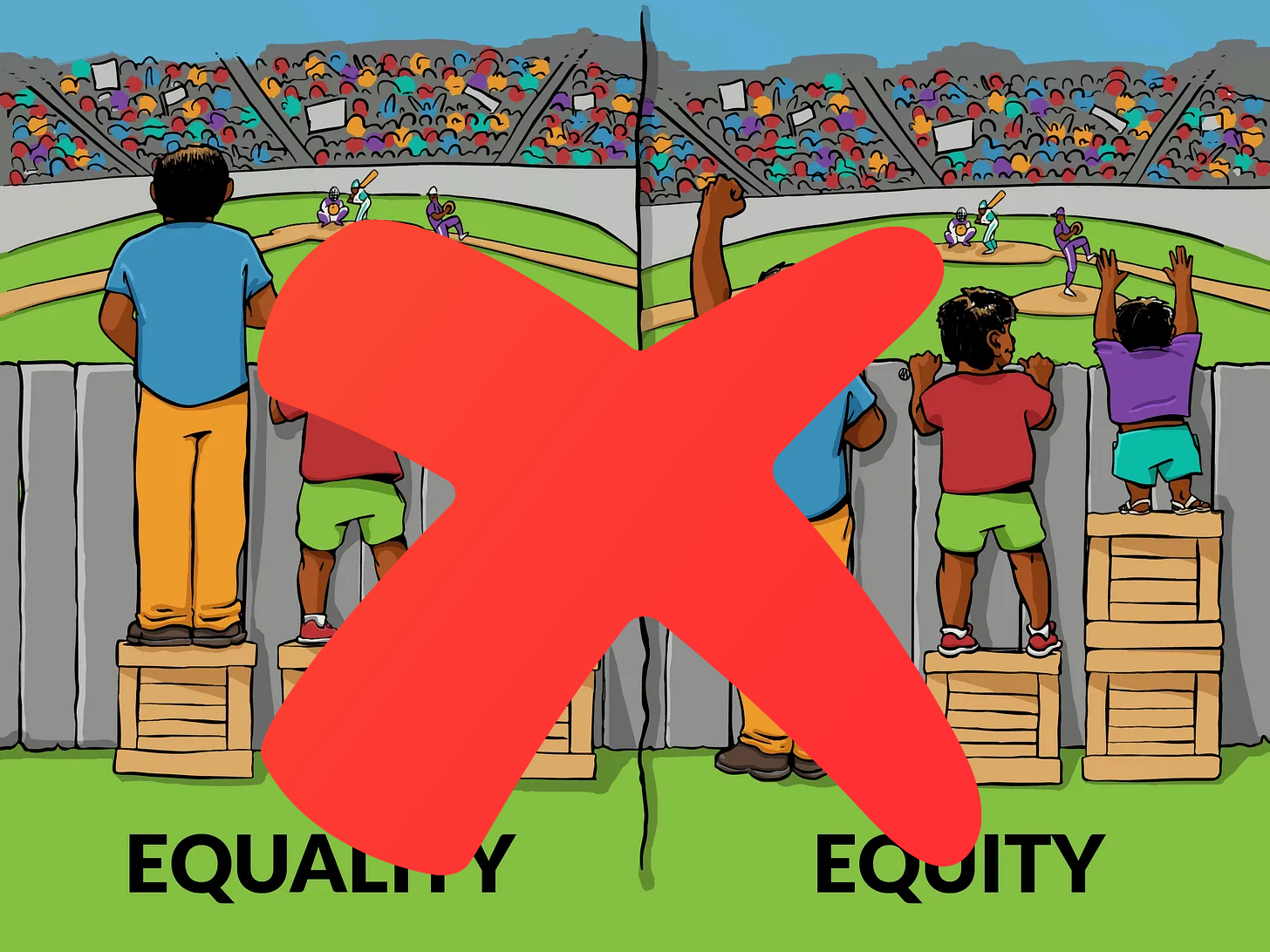

You don’t have to agree with this idea to see that it represents a very different way of thinking about equality

I’ve always been a bit uneasy about the above meme (to which I’ve added a red cross). Thankfully, due to link to a blog post by Rob Farrow I’ve discovered why. In fact, it’s possibly the reason why the whole DEI thing has been so contentious.

It shouldn’t need saying, but people don’t read carefully and aren’t used to reading beyond headlines these days. So before continuing of course I believe in equality. The issue is with the woolly concept of ‘equity’. The article I’m citing is by Joseph Heath, a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto. He writes as you’d expect such a person to write: clearly, but assuming a bit of a background in Philosophy. Thankfully, yours truly does have that background and is here to help 😉

The purpose of any good model is to present a simplified representation of reality, in order to accentuate crucial features and make them more analytically tractable. The question, therefore, is whether the kids on boxes provide a useful model for thinking about the sorts of distribution problems that arise in DEI contexts. Most egalitarian philosophers, I think, would say that it is a bad model.

I’ve taken the quotations out of order because the overall argument makes more sense when presented this way. So we start from the position that the kids on boxes meme isn’t particularly useful.

The contrast that is drawn in the meme, which was originally intended to illustrate the distinction between “equality of opportunity” and “equality of outcome,” captures the way that people used to think about issues of equality up until the late 1960s, before the publication of John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice in 1971. After that, pretty much everyone came to agree that the opportunity/outcome distinction was neither useful nor coherent. The really important question was not when one chose to equalize, but rather what one intended to equalize.

So we need to figure out what we’re ‘equalising’ here. Is it the number of boxes? Or the quality of view?

The most immediate problem with the meme is that it does not present an accepted definition of the term “equity,” but rather a stipulative redefinition, which does not correspond very well to how the term has historically been used… [T]he graphic was originally drawn to illustrate the contrast between equality of opportunity and equality of outcome. Later on, after it was reproduced umpteen times, someone changed the labels, and somehow the idea that “equality of outcome” should be called “equity” stuck.

To recap: we’ve got an outdated notion of ‘equality of opportunity’ vs ‘equality of outcome’ which has been made even more problematic by the meme relabelling the latter as ‘equity’. It’s not a defensible philosophical position, partly because ‘equity’ doesn’t have a universally accepted definition, and is usually seen as a looser standard that strict equality.

My suspicion is that when DEI ideas were first taking shape, people gravitated toward “equity” language precisely because it had this looseness about it. Because people are different (i.e. diverse), one should not expect perfect equality, but rather just equity. And for all I know, this may have been what the person who modified the kids on boxes meme was thinking, suggesting that the allocation of boxes to kids should be responsive to the different characteristics of the kids. The unfortunate result, however, is that instead of introducing a looser standard of equality, the meme wound up saddling DEI with a commitment to an extremely strict, controversial conception of equality (i.e. equality of outcome), which no reasonable person actually endorses as a general principle. Furthermore, this was not achieved through argument, but merely through persuasive definition.

And this, dear reader, is why Philosophy is such an important subject. If you don’t get these kinds of things right, then it has downstream implications. ‘Equity’ might seem like a reasonable thing to aim for, but if you don’t know what it means, then you’re going to run into trouble.

Setting aside these terminological issues and focusing on equality of outcome, the next big problem with the meme is that it commits DEI proponents to a conception of equality that is somewhere to the left of the most left-wing view defended by left-wing philosophers. Indeed, one of the major objectives of theorists in the “equality of what?” debate was to reformulate egalitarianism in such a way as to avoid the obvious objections to the simple-minded conception of equality of outcome that used to prevail in public debates (and that is represented nicely in the meme).

The ‘obvious objections’ mentioned above are things like people who have made poor choices in life. For example, intuitively, we don’t think that people who have made poor choices in life should be treated the same as those who have wound up with less because of circumstances beyond their control.

[Philosophers] took the choice/circumstance distinction and turned it into the fundamental justification for egalitarianism, arguing that our most basic reason for caring about equality is our desire to neutralize the effects of bad luck. According to this view, when we look at the kids on boxes meme and agree to take the box away from the tall guy and give it to the short kid, the reason we make this judgment is because height is an unchosen characteristic – it’s not the short kid’s fault that he’s short. The idea is not that everyone should get exactly the same outcome, but that we should not be allowing unchosen differences between persons to determine outcomes.

Framed like that, DEI would apply across the board, to people who face inequality through no fault of their own. It’s a shame that we took a meme-based approach to policy rather than a philosophical one. But then, we live in 2025 where only a small proportion of people are willing to take a nuanced view.

You don’t have to agree with this idea to see that it represents a very different way of thinking about equality. And from this perspective, the problem with the meme is that it dredges up an old, discredited view of equality, that can easily be undermined just by pointing to cases where individuals wind up with less because of choices they have made. A lot of the excitement generated by luck egalitarianism was based on the perception that we had overcome a significant error in thinking about equality, and could now move on to discussion of more defensible conceptions. And yet all it took was a single meme to turn back the clock by 50 years!

Source: In Due Course

Image: Modified from an original used in the above blog post.

I’m 100% positive people are going to talk to their cars

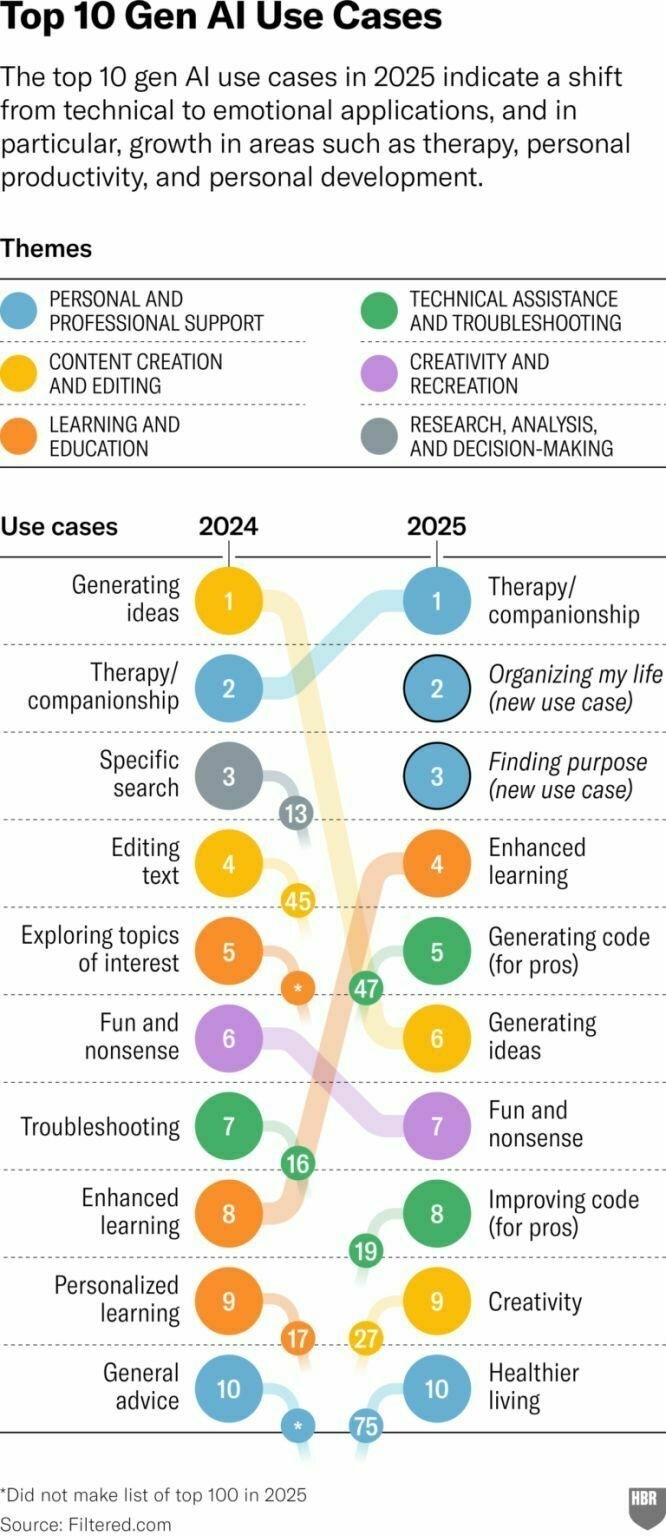

We live in the midst of a loneliness epidemic, especially for men. A recent Harvard Business Review article showed the difference between what people said they were using AI for this year, and compared to 2025.

“Generating ideas” has gone from first to sixth place, and “Therapy/companionship” has moved from second to first place. “Finding purpose” is a new use case coming straight in at third. There’s a paywall on the HBR article, so you can find the report here. Note that this was, in the words of the author, Marc Zao-Sanders, “a rigorous, expert-driven curation of public discourse, sourced primarily from Reddit forums.” No methodology is provided.

That being said, I’m using the report by way of introduction to the following extract from an article by Jay Springett, who reckons soon everybody will be talking to their car. I mean, I already talk to my Polestart 2 as it has Google Assistant built in, but he means talking in a deep and meaningful way.

For me, this is a case of not if, but when. It’s going to challenge notions of privacy, but also intimacy, infidelity, and loss (when providers inevitably shut down a service).

Consider the average American commuter: 60 minutes a day, mostly alone, in the car. The vehicle as liminal space. Neither home nor work. Private and intimate. I’m 100% positive people are going to talk to their cars. First for fun. Then for directions. Then about their lives. Their feelings. Their grief, their divorce.

And now that OpenAI has also introduced Memory (at least in the US) the car might remember everything you’ve ever told it. 😬

There’s a meaning crisis going on, which means there is a gaping emotional void waiting to be filled by a good listener that’s found in the safety of a car. Some people, especially men, already love their cars. What happens when the car appears to care for them back?

Her becomes a lot more plausible when the AI you fall in love with is also a car.

Source: thejaymo

Image: (shared by various people on LinkedIn)

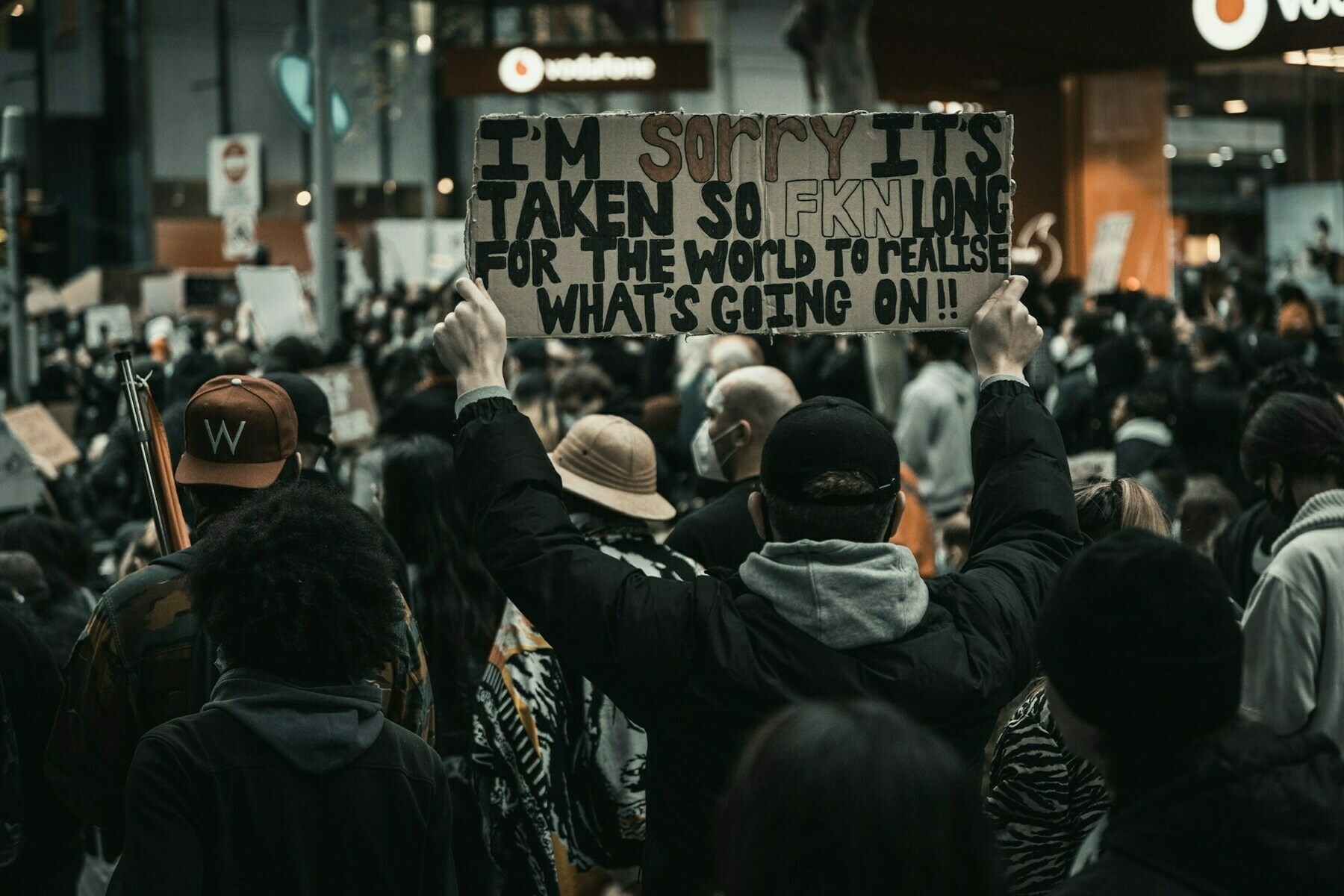

End times fascism is a darkly festive fatalism

It’s long, so I’ve provided a proportionally-long excerpt, but it really is worth taking the time to read this article by Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor about “end times fascism.” It’s a worldview that is simultaneously conspiratorial, eschatological, and profoundly anti-democratic.

I’m glad I don’t live in the USA at the moment, but I think we’re kidding ourselves if we don’t think that this kind of worldview isn’t aiming to capture a country like the UK soon. Carving up the world into multiple oligarchies suits rich people just fine. And the world can burn so long as they have air conditioning and a rocket ride outta here.

Inspired by a warped reading of the political philosopher Albert Hirschman, figures including Goff, Thiel and the investor and writer Balaji Srinivasan have been championing what they call “exit” – the principle that those with means have the right to walk away from the obligations of citizenship, especially taxes and burdensome regulation. Retooling and rebranding the old ambitions and privileges of empires, they dream of splintering governments and carving up the world into hyper-capitalist, democracy-free havens under the sole control of the supremely wealthy, protected by private mercenaries, serviced by AI robots and financed by cryptocurrencies.

[…]

The startup country contingent is clearly foreseeing a future marked by shocks, scarcity and collapse. Their high-tech private domains are essentially fortressed escape pods, designed for the select few to take advantage of every possible luxury and opportunity for human optimization, giving them and their children an edge in an increasingly barbarous future. To put it bluntly, the most powerful people in the world are preparing for the end of the world, an end they themselves are frenetically accelerating.

[…]

Our opponents know full well that we are entering an age of emergency, but have responded by embracing lethal yet self-serving delusions. Having bought into various apartheid fantasies of bunkered safety, they are choosing to let the Earth burn

[…]

Listen to Steve Bannon’s daily podcast – which bills itself as Maga’s premier media outlet – and you will be barraged with a singular message: the world is going to hell, the infidels are breaching the barricades, and a final battle is coming. Be prepared. The prepper message becomes particularly pronounced when Bannon switches to hawking his advertisers’ products. Buy Birch Gold, Bannon tells his audience, because the over-leveraged US economy is going to crash and you can’t trust the banks. Stock up on ready-to-eat meals from My Patriot Supply. Sharpen your target practice using a laser-guided at-home system. The last thing you would want to do is depend on the government during a disaster, he reminds listeners (left unsaid: especially now that the Doge boys are selling off the government for parts).

Bannon doesn’t only urge his audience to make their own bunkers, of course. He also advances a vision of the United States as a bunker in its own right, one in which Ice agents stalk the streets, workplaces and campuses, disappearing those deemed enemies of US policy and interests. The bunkered nation lies at the heart of the Maga agenda, and of end times fascism. Inside its logic, the first job is to harden national borders and expunge all enemies, foreign and domestic.

[…]

As fascism always does, today’s Armageddon complex crosses class lines, bonding billionaires to the Maga base. Thanks to decades of deepening economic stresses, alongside ceaseless and skillful messaging pitting workers against one another, a great many people understandably feel unable to protect themselves from the disintegration that surrounds them (no matter how many months of ready-to-eat meals they buy). But there are emotional compensations on offer: you can cheer the end of affirmative action and DEI, glorify mass deportation, enjoy the denial of gender-affirming care to trans people, villainize educators and health workers who think they know better than you, and applaud the demise of economic and environmental regulations as a way to own the libs. End times fascism is a darkly festive fatalism – a final refuge for those who find it easier to celebrate destruction than imagine living without supremacy.

[…]

Three recent material developments have accelerated end times fascism’s apocalyptic appeal. The first is the climate crisis. While some high-profile figures might still publicly deny or minimize the threat, global elites, whose ocean-front properties and datacenters are intensely vulnerable to rising temperatures and sea levels, are well-versed in the ramifying perils of an ever-heating world. The second is Covid-19: epidemiological models had long predicted the possibility of a pandemic devastating our globally networked world; the actual arrival of one was taken by many powerful people as a sign that we have officially arrived at what US military analysts forecasted as “the Age of Consequences”. No more predictions, it’s going down. The third factor is the rapid advancement and adoption of AI, a set of technologies that have long been associated with sci-fi terrors about machines turning on their makers with ruthless efficiency – fears expressed most forcefully by the same people who are developing these technologies. All of these existential crises are layered on top of escalating tensions between nuclear-armed powers.

So, er, what do we do about all this?

First, we help each other face the depth of the depravity that has gripped the hard right in all of our countries. To move forward with focus, we must first understand this simple fact: we are up against an ideology that has given up not only on the premise and promise of liberal democracy but on the livability of our shared world – on its beauty, on its people, on our children, on other species. The forces we are up against have made peace with mass death. They are treasonous to this world and its human and non-human inhabitants.

Second, we counter their apocalyptic narratives with a far better story about how to survive the hard times ahead without leaving anyone behind. A story capable of draining end times fascism of its gothic power and galvanizing a movement ready to put it all on the line for our collective survival. A story not of end times, but of better times; not of separation and supremacy, but of interdependence and belonging; not of escaping, but staying put and staying faithful to the troubled earthly reality in which we are enmeshed and bound.>

We have reached a choice point, not about whether we are facing apocalypse but what form it will take. […]

To have a hope of combating the end times fascists […] we will need to build an unruly open-hearted movement of the Earth-loving faithful: faithful to this planet, its people, its creatures and to the possibility of a livable future for us all. Faithful to here.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Arctic Qu

Nobody should have to pay to be safe while using a computer

Yesterday, as happens on a regular basis, there was an update to Tails, “the amnesiac incognito live system.” I mention this because much of our digital life is online, and many of the systems we use are not only hostile to users, but are backed by organisations with links to authoritarian regimes and surveillance capitalism.

If I was travelling to China, the US, or Russia, or indeed was a citizen of countries with authoritarian tendencies, this would be what I’d be using to cover my back. As Cardinal Richelieu famously said, “Give me six lines written by the most honest man in the world, and I will find enough in them to hang him." These days, our digital footprint gives people with a grudge, an axe to grind, or a particular agenda, _much_more than “six lines”. Protect yourself proactively.

To use Tails, shut down the computer and start on your Tails USB stick instead of starting on Windows, macOS, or Linux. You can temporarily turn your own computer into a secure machine. You can also stay safe while using the computer of somebody else.

Tails always starts from the same clean state and everything you do disappears automatically when you shut down Tails.

Tails includes a selection of applications to work on sensitive documents and communicate securely. All the applications are ready-to-use and are configured with safe defaults to prevent mistakes.

Everything you do on the Internet from Tails goes through the Tor network. Tor encrypts and anonymizes your connection by passing it through 3 relays. Relays are servers operated by different people and organizations around the world.

Tor prevents someone watching your Internet connection from learning what you are doing on the Internet. You can avoid censorship because it is impossible for a censor to know which websites you are visiting.

Tor also prevents the websites that you are visiting from learning where and who you are, unless you tell them. You can visit websites anonymously or change your identity. Online trackers and advertisers won’t be able to follow you around from one website to another anymore.

All the code of our software is public to allow independent security researchers to verify that Tails really works the way it should.

Nobody should have to pay to be safe while using a computer. That is why we are giving out Tails for free and try to make it easy to use by anybody. Tails is made by the Tor Project, a global nonprofit developing tools for online privacy and anonymity.

Source & image: Tails

AI Literacy without power analysis is just compliance training

I’m working on an AI Literacy project with the BBC at the moment. I haven’t given many details of this anywhere, as they need to socialise internally that the work is happening first. But I’m really enjoying getting my teeth back into the new literacies space.

For years now, I’ve included in my presentations the fact that when you define ‘literacy’ you’re making a power move. You’re either explicitly or implicitly saying what counts as “literate behaviour.”

That’s why I’m in agreement with James O’Hagan’s position in this article. It chimes the point I made earlier this week about it being a good thing that young people are using AI for their own ends. They need a space to push back at simple ‘compliance training’ on how to use tools, to develop critical AI Literacies (plural!)

There is a reason why the dominant models of AI literacy being promoted to schools feel so hollow. They focus on functionality, not freedom. They train students to use the tools, not challenge the systems. They offer guardrails, not agency.

In one of my Medium pieces, I argued that we are designing AI literacy to make education compliant, not smarter. That is still the case. What often gets labeled “AI education” is really just exposure — watching a tool work, seeing a demo, reading a definition. For example, I completed all five MagicSchool AI certification courses in under 15 minutes — without ever logging in or using the platform. That says more about the training than it does about the tool.

Very little of this equips students to intervene. To resist. To build differently.

We need AI literacy that makes students dangerous thinkers, not docile users.

[…]

Let students ask who funds the tools. Who sets the limits. Who benefits. Let them critique the platforms that shape their school day. Let them design alternatives rooted in their experiences. And let us stop pretending that integration is progress if the terms are dictated from the outside.

We can — and must — teach the technical. But we should not stop there. We need to lift the hood, yes. But we also need to ask why the engine was built in the first place, who it leaves behind, and where it refuses to go.

The way we talk about AI in education will shape the way we teach it. If we treat it like magic, we will mystify. If we treat it like software, we will standardize. But if we treat it like a political, social, and ethical terrain, we will start to give students the tools to navigate it — and challenge it.

Source: James O’Hagan

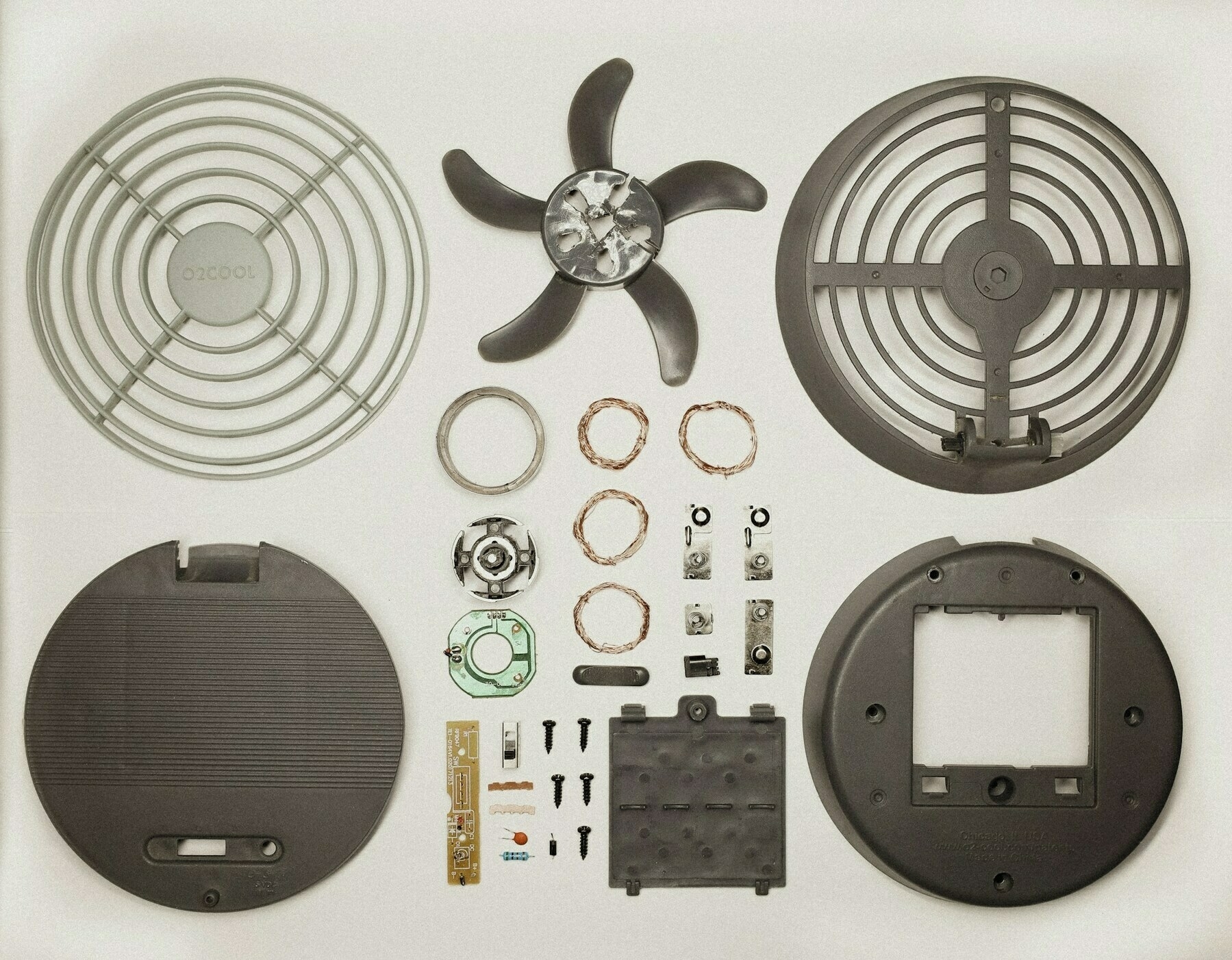

The world is a built environment

Dan Sinker uses this blog post to discuss US politics and the systematic dismantling of important infrastructure. But I’m interested in the wider framing of understanding that you can take things apart, literally and figuratively. As Steve Jobs said, everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you.

Most everything I know, I know because I took something apart.

I mean that literally: I’ve cut and I’ve unscrewed and I’ve pried and I’ve desoldered to get inside electronics and appliances. And I mean it figuratively: I read the source code for web pages to build my own, I’ve deconstructed writing to make myself better at it, I’ve mapped entire audio stories with pen and paper to understand how to assemble them myself.

If I want to really understand something, I have to understand all the pieces that went into making it come together.

[…]

Everything can be taken apart, and every step of the process is an opportunity to learn.

The world is a built environment, and I think understanding how it was built is key to being able to truly live in it.

Source: Dan Sinker

Image: KAT

It will be increasingly difficult to preserve the illusion that any government could solve the problems of capitalism

Adam Procter sent me this video which explains the ‘squeeze out’ that’s been happening over the last 30 years or so. It happens in five stages:

- The rich start to accumulate more money, as they are not taxed enough. They buy up assets, out-competing the working classes for resources, and driving them into debt.

- The working classes have run out of money and cannot borrow or spend any more, so there is an economic depression and a crisis. So the government has to step in.

- The government starts to run out of resources as well, so borrows from (or enters into public-private partnerships with) the rich.

- The government has no choice but to slowly eviscerate the middle classes. Eventually there is no wealth left other than that held by the rich, meaning that the physical structure of society changes so that it only supports consumption by them.

- There is no-one left to squeeze. The rich own everything, and the only way they can try and grow their wealth is by sending people to fight in wars against each other.

Like Cory Doctorow’s three stages of enshittification it’s a useful overview of a process that would otherwise be difficult to pin down. Is it 100% accurate everywhere and all of the time? No, probably not, but it’s a useful framing.

Given the absolute destruction of the world and dismantling of civil society that’s happening at the moment, I’m a little bit less reticent to state that I’m an anarchist. Not like the ridiculous caricature of anarchists as terrorists and in books like The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton (which is otherwise an enjoyable novel). Nor am I out there actively fermenting trouble. But that broadly libertarian socialist angle is my starting position for understanding how the world should be.

If there was ever a time to be reading more revolutionary stuff, it’s now. So I’m pointing you towards Crimethinc. “a rebel alliance—a decentralized network pledged to anonymous collective action—a breakout from the prisons of our age.”

The future may hold neoliberal immiseration, nationalist enclaves, totalitarian command economies, or the anarchist abolition of property itself—it will probably include all of those—but it will be increasingly difficult to preserve the illusion that any government could solve the problems of capitalism for any but a privileged few. Fascists and other nationalists are eager to capitalize on this disillusionment to promote their own brands of exclusionary socialism; we should not smooth the way for them by legitimizing the idea that the state could serve working people if only it were properly administered.

[…]

Rather than seeking state power, we can open up spaces of autonomy, stripping legitimacy from the state and developing the capacity to meet our needs directly. Instead of dictatorships and armies, we can build worldwide rhizomatic networks to defend each other against anyone who wants to wield power over us. Rather than looking to new representatives to solve our problems, we can create grassroots associations based in voluntary cooperation and mutual aid. In place of state-managed economies, we can establish new commons on a horizontal basis. This is the anarchist alternative, which could have succeeded in Spain in the 1930s had it not been stomped out by Franco on one side and Stalin on the other.

[…]

As the crises of our era intensify, new revolutionary struggles are bound to break out. Anarchism is the only proposition for revolutionary change that has not sullied itself in a sea of blood. It’s up to us to update it for the new millennium, lest we all be condemned to repeat the past.

Source: Crimethinc.

That's a rather laughable fine, frankly

A couple of months ago, a report that Laura and I wrote for Friends of the Earth was published. Focusing on AI and environmental justice, in collaboration with experts and campaigners, we came up with seven principles:

- Curiosity around AI creates opportunities for better choices.

- Transparency around usage, data and algorithms builds trust.

- Holding tech companies and governments accountable leads to responsible action.

- Including diverse voices strengthens decision making around AI.

- Sustainability in AI systems helps reduce environmental impact and protect natural ecosystems.

- Community collaboration in AI is key to planetary resilience.

- Advocating with an intersectional approach supports humane AI.

That third point is really important, and as this article shows, merely fining tech companies isn’t enough.

Apparently, Elon Musk’s company xAI is using methane-burning gas turbines to fuel over a data centre at a site in Tennessee. As the generators are classed as ‘portable’ they can be used for up to 364 days. At the time of writing, xAI only has permits for the use of 15 generators, but they’re currently using 35. That’s terrible for the environment.

The proximity of powerful tech companies to right-wing authoritarianism is one of the reasons we ended up with the Holocaust. In a recent newsletter, Audrey Watters pointed to this article where the authors introduce the TESCREAL bundle (“transhumanism, Extropianism, singularitarianism, (modern) cosmism, Rationalism, Effective Altruism, and longtermism”). They consider these beliefs to be “direct descendants of first-wave eugenics.” Plenty of concepts to look up there, but the TL;DR is that “much of the billionaire funding for projects focused on AGI comes from wealthy individuals aligned or explicitly affiliated with one or more of these ideologies.”

Last year it turned out that Elon Musk’s xAI had to install additional ‘portable’ generators near its facility adjacent to Memphis, Tennessee, to power the Colossus supercomputer with over 100,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs as local power grid could not support the load. The Southern Environmental Law Center contends the generators are “illegal,” yet they can keep running, reports The Guardian.

[…]

The law center stated in a letter that these generators are a major pollution source and breach federal air quality rules, including emissions of hazardous and cancer-causing substances. They demanded that the local health agency issue an emergency halt to the operations and fine the company $25,000 for every day it continues to run them without proper authorization.

That’s a rather laughable fine, frankly. The 100,000 H100 GPUs in the xAI Colossus would cost about $2.5 billion on their own — never mind the rest of the data center infrastructure and hardware. $25,000 per day would amount to just $9.1 million per year. Providing 150MW of electricity, 24/7, on the other hand, even at a price of $0.05 per kWh (we’re not sure what xAI pays to run the portable generators) would be about $180,000 per day.

Source: Tom’s Hardware

Image: Logan Voss