'Restorying' your life as a hero's journey

There are some people, perhaps most people, who do not expect setbacks and problems in life. They seem to think that it should all be smooth sailing, and that anything that interferes with this unarticulated plan is somehow annoying or unfair.

Perhaps because I spent my teenage years reading philosophy (which I studied at university) and then my adult life reading Stoic philosophers such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, this isn’t my view. Instead, I’m well aware that everyone has to deal with setbacks and, in fact, they make you stronger and more focused.

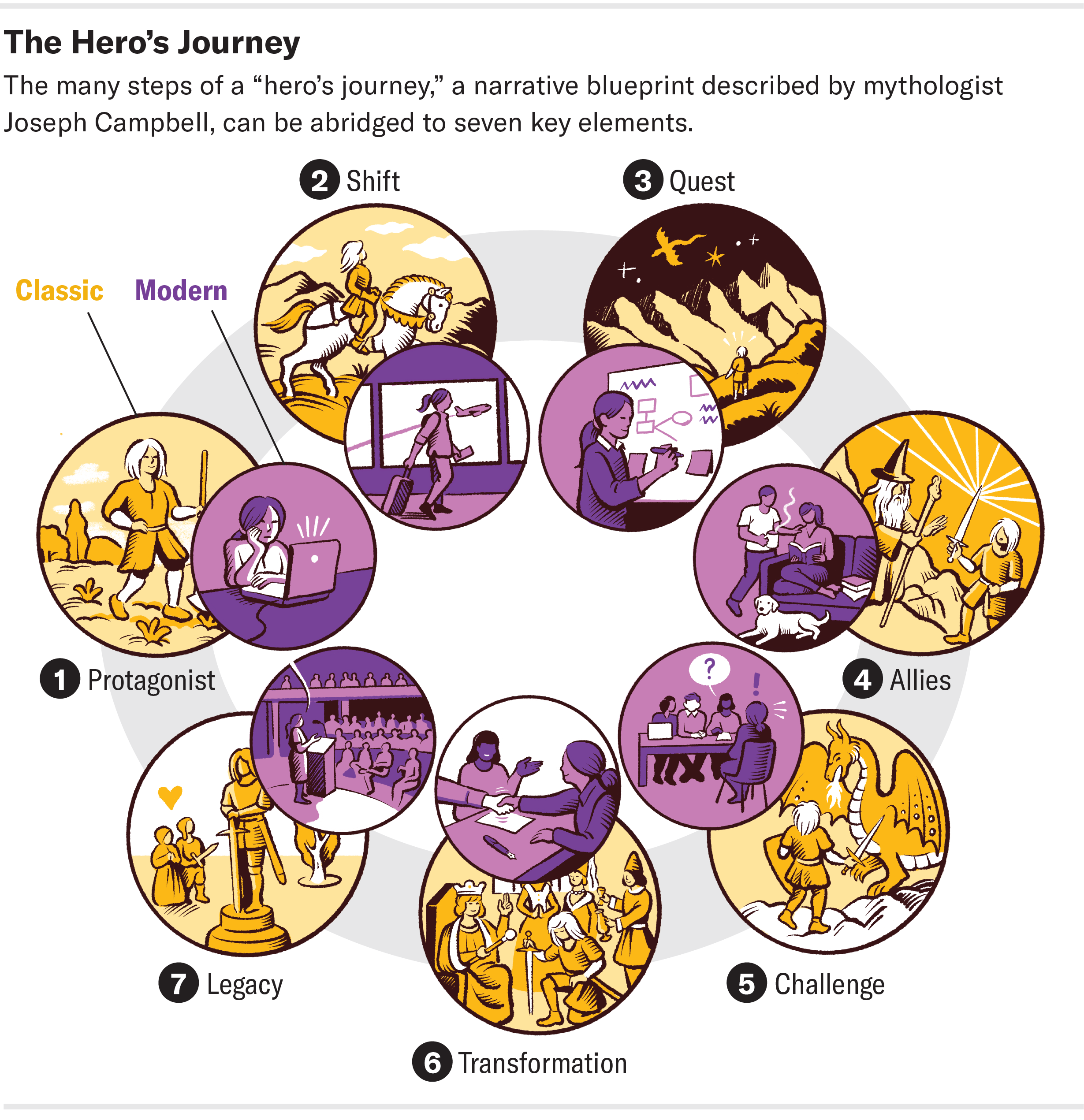

This article discusses the results of research based on interventions taking as its basis The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell. He noticed that cultures around the world had foundational stories which were based on a similar structure. The researchers took this approach, updated it for modern life, and used the structure as an intervention to help individuals to tell better stories about their lives.

What do Beowulf, Batman and Barbie all have in common? Ancient legends, comic book sagas and blockbuster movies alike share a storytelling blueprint called “the hero’s journey.” This timeless narrative structure, first described by mythologist Joseph Campbell in 1949, describes ancient epics, such as the Odyssey and the Epic of Gilgamesh, and modern favorites, including the Harry Potter, Star Wars and Lord of the Rings series. Many hero’s journey stories have become cultural touchstones that influence how people think about their world and themselves.Source: To Lead a Meaningful Life, Become Your Own Hero | Scientific AmericanOur research reveals that the hero’s journey is not just for legends and superheroes. In a recent study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, we show that people who frame their own life as a hero’s journey find more meaning in it. This insight led us to develop a “restorying” intervention to enrich individuals’ sense of meaning and well-being. When people start to see their own lives as heroic quests, we discovered, they also report less depression and can cope better with life’s challenges.

[…]

To explore the connection between people’s life stories and the hero’s journey, we first had to simplify the storytelling arc from Campbell’s original formulation, which featured 17 steps. Some of the steps in the original set were very specific, such as undertaking a “magic flight” after completing a quest. Think of Dorothy, in the novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, being carried by flying monkeys to the Emerald City after vanquishing the Wicked Witch of the West. Others are out of touch with contemporary culture, such as encountering “women as temptresses.” We abridged and condensed the 17 steps into seven elements that can be found both in legends and everyday life: a lead protagonist, a shift of circumstances, a quest, a challenge, allies, a personal transformation and a resulting legacy.

For example, in The Lord of the Rings, Frodo (the protagonist) leaves the Shire (a shift) to destroy the Ring (a quest). Sam and Gandalf (his allies) help him face Sauron’s forces (a challenge). He discovers unexpected inner strength (a transformation) and then returns home to help the friends he left behind (a legacy). In a parallel way in everyday life, a young woman (the protagonist) might move to Los Angeles (a shift), develop an idea for a new business (a quest), get support from her family and new friends (her allies), overcome self-doubt after initial failure (a challenge), grow into a confident and successful leader (a transformation) and then help her community (a legacy).

[…]

Anyone can frame their life as a hero’s journey—and we suspect that people can also benefit from taking small steps toward a more heroic life. You can see yourself as a heroic protagonist, for example, by identifying your values and keeping them top of mind in daily life. You can lean into friendships and new experiences. You can set goals much like those of classic quests to stay motivated—and challenge yourself to improve your skills. You can also take stock of lessons learned and ways that you might leave a positive legacy for your community or loved ones.

The real threat to manhood: remaining children

This is an interesting article that, to be honest, I expected a bit more from. It comments on some obvious things such as how problematic a rigid and joyless form of ultra-masculinity can be, as well as being careful not to say that discipline isn’t important.

While I appreciate that the author, Dave Holmes, doesn’t use the term ‘toxic masculinity’ (which I think doesn’t really mean anything any more) what I do think he could have developed further is the very last line. In it, he mentions that the real threat to manhood is us “staying children” which is a much more interesting area to explore.

The world is more individualised, gamified, and commercialised than ever before. Masculinity, as a concept, is therefore an idea to be bought and sold. The version we need to fix the world is not the version that gains the most likes on social media; it’s one that is confident, self-reflective, and biased towards helping others.

You can be forgiven for not noticing that men aren’t men anymore, because men are always not men anymore. “Men aren’t men anymore”—like “nobody younger than me wants to work” and “this isn’t real music”—has been said every day in every language since we’ve had days and languages. It’s a particular concern in America, where men haven’t been men anymore from the jump. Almost certainly one of our founding fathers told his son, “Don’t leave this house without your wig, stockings, and frock coat—I didn’t raise a sissy.”Source: Can You Still Say ‘Be A Man’? | Esquire[…]

“Men are not men anymore” is ancient; “men are not men anymore, buy this and fix that,” slightly newer. But this is a much bleaker time, a time of “men are not men anymore, smash that subscribe button.” A generation of boys looking for rules has met a generation of creeps looking for an audience: Jordan Peterson, Steven Crowder, Andrew Tate. Guys who offer a rigid and joyless version of masculinity. Guys whose brand says, “I have learned how to throttle everything that is exuberant and playful within myself to become someone else’s version of what a man is; what’s wrong with you?” Guys who have chosen a car for its color and will never forgive themselves for it.

[…]

This is not to say you should throw away rules, or that playing to a person’s insecurity isn’t sometimes the right move. I quit smoking at 30, cold turkey, unless I was in a bar, or walking home after a good meal, or near someone who asked, “Would you like a cigarette?” My friend Lee picked up on this. “For someone who has quit smoking,” he said, “you are doing a lot of smoking.” I protested, “It’s just hard in certain situations.” Lee looked me in the eye and said, “Have you tried being a man?” Haven’t had a cigarette since.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Lee aren’t saying independent thinking and discipline are virtues for men as opposed to women. They are just virtues. Rules for good living. Like we aim to provide in the Esquire of 2023. It’s time we stop being so worried about becoming women and start focusing on the real threat to manhood: staying children.

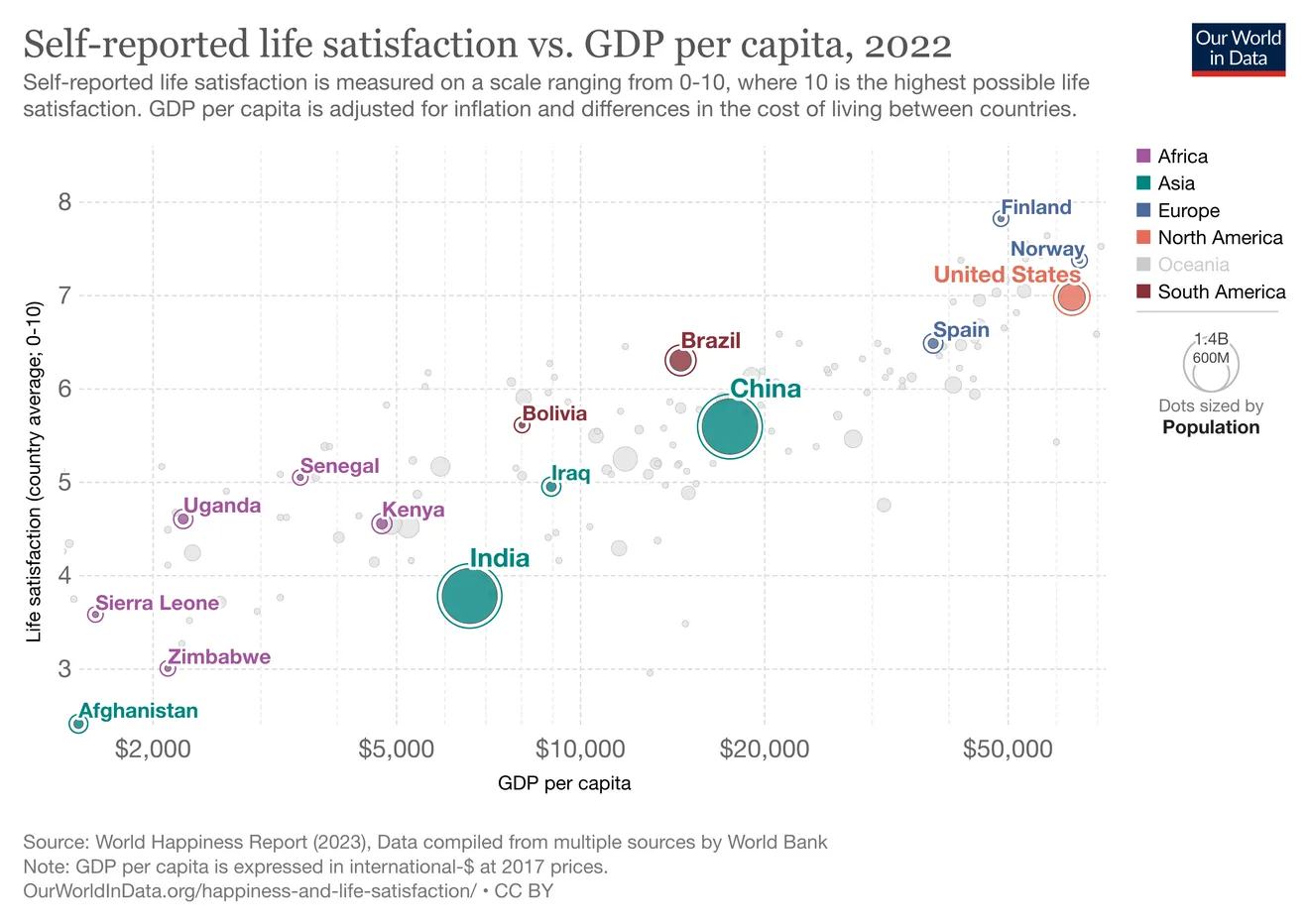

Happiness vs GDP

Making the world a happier, fairer, safer place seems like an idea that most people can get behind. But how do you do it? Although there’s a relationship between average self-reported happiness of a population and increased GDP per capita, there are notable outliers.

So, what to do? Focus on other numbers as well. This article talks about measuring ‘Wellbys’ or ‘well-being-life-adjusted-years’ which involves placing a lot more emphasis on subjective numbers.

The trouble, as anyone who has visited a hospital in England will know, is that self-reported data while useful can be very problematic. For example, when I go into hospital, I know that they will ask me to rate my pain on a scale of 1-10. Being a reasonably stoic kind of person, I used to keep that number low, which not only kept me at the back of the line for being seen, but meant they were less likely to give me painkillers.

Guess what I’ve learned to do? Yep, game the system. People respond to incentives, so although trying to make single numbers go up and to the right might make life easier for those intervening in systems, it doesn’t make those interventions any more effective.

Instead, I’d like to see the focus more on something like the Human Development Index (HDI) which, not only has been around for a while, but is a composite of statistics designed to increase human flourishing.

As we’ve gathered more data on the happiness of different populations, it’s become clear that increasing wealth and health do not always go hand in hand with increasing happiness. By the economists’ objective measures, people in rich countries like the US should be doing great — and yet Americans are only becoming more miserable. And people in some higher-GDP European countries like Portugal and Italy report lower life satisfaction than people in lower-GDP Latin American countries.Source: Make people happier — not just wealthier and healthier | VoxWhat’s going on here? How do we explain the gaps in life satisfaction that objective metrics like GDP don’t explain?

Nowadays, a growing chorus of experts argues that helping people is ultimately about making them happier — not just wealthier or healthier — and the best way to find out how happy people are is to just ask them directly. This camp says we should focus a lot more on subjective well-being: how happy people are, or how satisfied they are with their lives, based on what they say matters most to them — not just based on objective metrics like GDP. Subjective well-being can tell us things that objective metrics can’t.

[…]

Instead, [Michael} Plant [who leads the Happier Lives Institute] argues we should compare how much good different things do in a single “currency” — specifically, how many well-being-adjusted life years, or Wellbys, they produce. Producing one Wellby means increasing life satisfaction by one point (on the 0-10 life satisfaction scale) for one year. It’s a metric that some economists, including those behind the World Happiness Report, are coming to embrace. If we were to evaluate every policy in terms of how many Wellbys it produces, that would allow for direct apples-to-apples comparisons.

“I’m pretty bullish about just using well-being as the [single] measure,” Plant told me.

The Fediverse model can help fix the internet

This article in the MIT Technology Review largely comes to the same conclusions as my comment in another Thought Shrapnel post today. If the web is broken because of tracking, and that tracking comes from advertising funding the web, then we need a better way of funding the web.

Big Tech wants that to be user subscriptions. But there’s a federated network of instances out there called the Fediverse which will, inevitably, be around longer than any particular social network. So you might as well get onboard now.

The existential problem is that both the best and worst parts of the internet exist for the same set of reasons, were developed with many of the same resources, and often grew in conjunction with each other. So where did the sickness come from? How did the internet get so … nasty? To untangle this, we have to go back to the early days of online discourse.Source: How to fix the internet | MIT Technology Review[…]

In 1999, the ad company DoubleClick was planning to combine personal data with tracking cookies to follow people around the web so it could target its ads more effectively. This changed what people thought was possible. It turned the cookie, originally a neutral technology for storing Web data locally on users’ computers, into something used for tracking individuals across the internet for the purpose of monetizing them.

[…]

Our modern internet is built on highly targeted advertising using our personal data. That is what makes it free. The social platforms, most digital publishers, Google—all run on ad revenue. For the social platforms and Google, their business model is to deliver highly sophisticated targeted ads. (And business is good: in addition to Google’s billions, Meta took in $116 billion in revenue for 2022. Nearly half the people living on planet Earth are monthly active users of a Meta-owned product.) Meanwhile, the sheer extent of the personal data we happily hand over to them in exchange for using their services for free would make people from the year 2000 drop their flip phones in shock.

[…]

When we think of what’s most obviously broken about the internet—harassment and abuse; its role in the rise of political extremism, polarization, and the spread of misinformation; the harmful effects of Instagram on the mental health of teenage girls—the connection to advertising may not seem immediate. And in fact, advertising can sometimes have a mitigating effect: Coca-Cola doesn’t want to run ads next to Nazis, so platforms develop mechanisms to keep them away.

But online advertising demands attention above all else, and it has ultimately enabled and nurtured all the worst of the worst kinds of stuff. Social platforms were incentivized to grow their user base and attract as many eyeballs as possible for as long as possible to serve ever more ads. Or, more accurately, to serve ever more you to advertisers. To accomplish this, the platforms have designed algorithms to keep us scrolling and clicking, the result of which has played into some of humanity’s worst inclinations.

Paying to avoid ads is paying to avoid tracking

This article is the standard way of reporting Meta’s announcement that, to comply with a new EU ruling, they will allow users to pay not to be shown adverts. It’s likely that only privacy-minded and better-off people are likely to do so, given the size of the charge.

What isn’t mentioned in this type of article, but which TechCrunch helpfully notes, is that the issue is really about tracking. By introducing a charge, Meta hopes that they can gain legitimate consent for users to be tracked so as to avoid a monthly fee.

X, formerly Twitter, is also trialling a monthly subscription. Of course, if you’re going to pay for your social media, why not set up your own Fediverse instance, or donate to a friendly admin who runs it for you. I do the latter with social.coop.

Meta is responding to "evolving European regulations" by introducing a premium subscription option for Facebook and Instagram from Nov. 1.Source: Meta Introduces Ad-Free Subscription for Facebook, Instagram | PC MagazineAnyone over the age of 18 who resides in the European Union (EU), European Economic Area (EEA), or Switzerland will be able to pay a monthly subscription in order to stop seeing ads. Meta states that “while people are subscribed, their information will not be used for ads.”

[…]

Subscribing via the web costs around $10.50 per month, but subscribing on an Android or iOS device pushes the cost up to almost $14 per month. The difference in price is down to the commission Apple and Google charge for in-app payments.

The monthly charge covers all linked accounts in a user’s Accounts Center. However, that only applies until March 1 next year. After that, an extra $6 per month will be payable for each additional account listed in a user’s Accounts Center. That extra charge increases to $8.50 per month on Android and iOS.

Image: Unsplash

Looking out of someone else's window

Well, this is absolutely delightful.

The view below is from a window of Hotel Washington looking out over the monument in Washington D.C. but there are others that include just random people’s back gardens.

Open a new window somewhere in the worldSource: WindowSwap

Soul houses and false doors

Egyptology is endlessly fascinating to me. I only got to scratch the surface teaching a course called Medicine Through Time as a History teacher fifteen years ago, but it’s something I’ll perhaps return to in my retirement.

I’m not sure which time period you’d like to go and have a look at (not live in, that’s a different thing entirely) but for me it’s Ancient Egypt. It all seems so other-worldly.

The Ancient Egyptians world they inhabited with innumerable otherworldly entities: invisible, yet with immense power. Demons haunted the desert wastes and goddesses dwelled in the marshes of the Nile Delta, but the spirits of the dead were omnipresent. Ancestor worship was an important part of household religion and the belief that the dead could not only be communicated with, but could also use their power to both help and hurt living beings, was an ingrained part of the ancient Egyptian belief system.Source: In Ancient Egypt, Soul Houses and False Doors Connected the Living and the Dead | Atlas Obscura[…]

False doors were a specific type of funerary decoration often found in the tombs of the Egyptian elite during the Old Kingdom, the period more than 4,000 years ago when the Giza pyramids were built. False doors were carved from a single piece of limestone and took the form of a narrow doorway surrounded by inscribed door jambs and surmounted by a lintel. The tomb’s occupant was usually represented seated at a table laden with food offerings: vegetables, fruits, bread, wine, beer, and meats—everything a soul would need to sustain itself in the afterlife. The family members and friends of the deceased could also be immortalized on the false door. These carvings were not portraits, however, but idealized representations. Both men and women were shown in the prime of their life: strong, healthy, vigorous, and fertile.

[…]

False doors were generally the preserve of the extreme elite, those state officials who could afford to hire artists and craftspeople to build their multichambered stone tombs. The vast majority of the population of Egypt had no such resources. But they too required a way to magically pass offerings from the living world to sustain the souls of their ancestors in the afterlife.

In place of stone, they turned to the muddy clay of the Nile, of which there was an abundance. Carefully, they crafted and fired small models of houses complete with courtyards. They filled the courtyards with models of bread and vegetables, grain bins and pots filled with beer. Then they placed these objects, collectively known as soul houses, on top of the graves of their family and friends. The soul houses became imbued with magic and through them, food offerings could pass between the worlds of the living and the worlds of the dead. They are simple objects, but they show that the ordinary ancient Egyptians were every bit as concerned as the social elites with providing for their ancestors in the afterlife.

Stonehenge had nothing to do with druids

I’ve only ever driven past Stonehenge, as it’s a long way from where I grew up, and by the time I was old enough to go independently there were all sorts of restrictions around it.

It’s been interesting over my lifetime to see how the understanding of its significance has changed, especially as other henges and monuments have been found nearby.

Seventeenth-century English antiquarians thought that Stonehenge was built by Celtic Druids. They were relying on the earliest written history they had: Julius Caesar’s narrative of his two unsuccessful invasions of Britain in 54 and 55 BC. Caesar had said the local priests were called Druids. John Aubrey (1626–1697) and William Stukeley (1687–1765) cemented the Stonehenge/Druid connection, while self-styled bard Edward Williams (1747–1826), who changed his name to Iolo Morganwg, invented “authentic” Druidic rituals.Source: Stonehenge Before the Druids (Long, Long, Before The Druids) | JSTOR Daily[…]

“The false association of [Stonehenge] with the Druids has persisted to the present day,” [historian Carole M.] Cusak writes, “and has become a form of folklore or folk-memory that has enabled modern Druids to obtain access and a degree of respect in their interactions with Stonehenge and other megalithic sites.”

Meanwhile, archaeologists continue to explore the centuries of construction at Stonehenge and related sites like Durrington Walls and the Avenue that connects Stonehenge to the River Avon. Neolithic Britons seem to have come together to transform Stonehenge into the ring of giant stones—some from 180 miles away—we know today. Questions about construction and chronology continue, but current archeological thinking is dominated by findings and analyses of the Stonehenge Riverside Project of 2004–2009. The Stonehenge Riverside Project’s surveys and excavations made up the first major archeological explorations of Stonehenge and surroundings since the 1980s. The project archaeologists postulate that Stonehenge was a long-term cemetery for cremated remains, with Durrington Walls serving as the residencies and feasting center for its builders.

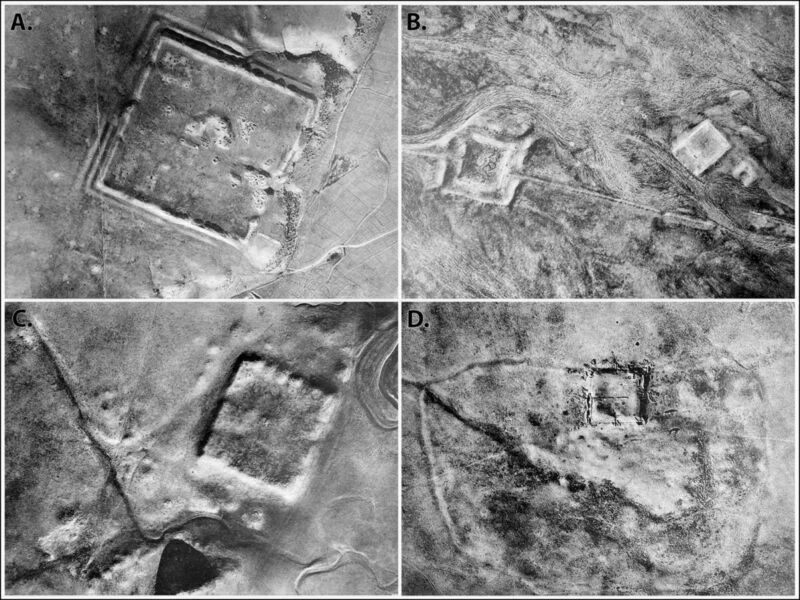

The French Jesuit priest who surveyed Roman forts by air

I’m not sure what’s more fascinating: the scale of the Roman army’s building (in this case, in Syria) or the French Jesuit priest who surveyed them by aeroplane.

Either way, the history geek in me loves this.

Back in the early days of aerial archaeology, a French Jesuit priest named Antoine Poidebard flew a biplane over the northern Fertile Crescent to conduct one of the first aerial surveys. He documented 116 ancient Roman forts spanning what is now western Syria to northwestern Iraq and concluded that they were constructed to secure the borders of the Roman Empire in that region.Source: I spy with my Cold War satellite eye… nearly 400 Roman forts in the Middle East | Ars TechnicaNow, anthropologists from Dartmouth have analyzed declassified spy satellite imagery dating from the Cold War, identifying 396 Roman forts, according to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity. And they have come to a different conclusion about the site distribution: the forts were constructed along trade routes to ensure the safe passage of people and goods.

[…]

The Dartmouth team analyzed CORONA and HEXAGON images covering some 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 square miles) in the northern Fertile Crescent, mapping 4,500 known archaeological sites and other features that seemed to be sites of interest. Some 10,000 previously undiscovered sites were added to their database. Poidebard’s forts have their own category in that database, based on their distinctive square shape and size, and the Dartmouth researchers found many more likely forts lurking in the spy satellite imagery.

The results confirmed Poidebard’s 1934 finding of a line of forts running along the strata Dioceltiana and also revealed several new forts along that route. But the survey also showed many new, previously undetected Roman forts running west-southwest between the Euphrates Valley and western Syria, as well as connecting the Tigris and Khabur rivers. That seems more suggestive of the forts supporting the movement of troops, supplies, or trade goods across the Fertile Crescent—cultural exchange sites rather than barriers. The authors date most of the forts to between the second and sixth centuries CE, after which there was widespread abandonment of the sites, although a few remained occupied into the medieval period.

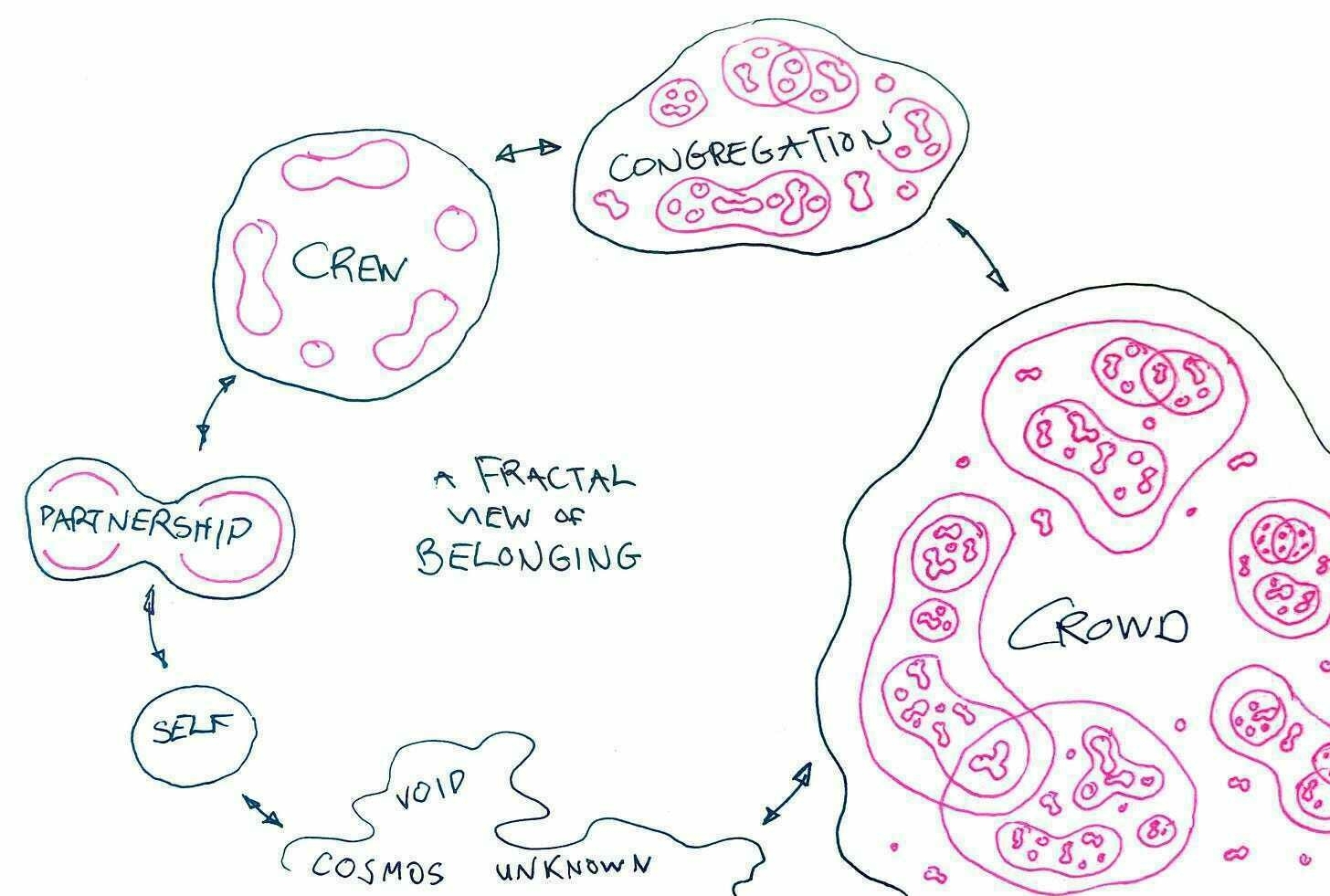

Superorganisms and solidarity

I haven’t gone enough into Buddhism to understand whether what is described in this article by Richard D. Bartlett constitutes as secular version of it, but from my limited knowledge, it would appear so.

That’s not in any way to downplay the important insights that Rich brings to the fore in his writing. For example, asking the question about group dynamics when some or all of the group drinks strong coffee. Or wondering what the largest group is that can hold a single conversation.

Fascinating stuff, and firmly in the realm of philosophy of conviviality and solidarity. One to return to.

I want you to see your self as a superorganism. And I want you to see the superorganisms that you are part of. I want the perceived boundaries of your self to leak.Source: Seeing Like a Superorganism | Richard D. BartlettI want you to see how your agency is not a tidy black box contained inside the envelope of your skin, but distributed in a network, intra-penetrating with other people. I want you to feel the incorporeal beings steering your choices, and I want you to learn that you can steer their choices too.

[…]

Just as a we can see the distinct layers of “cell”, “tissue” and “organ” at the micro-scales, I want you to see the distinct layers at the macro-scale. I want you to see that a group of 5 people is a distinct superorganism with distinct competencies. A group of 150 people is another species of superorganism, it can do other things.

You may be thinking to yourself, what the fuck are you talking about Rich? I can’t explain it, you have to see for yourself. Maybe I can give you some instructions to help you see like a superorganism.

Serious art, influencers, and AI

This is quite the article by Rob Horning. It begins with a social media spat between an influencer and an art critic, takes a brief detour into the philosophy of modernism, and ends with a discussion of AI-produced representations of the world.

I think Horning could turn this into a short book, particularly if he considers studies which show that the historical value of artworks and the critical reception of artists' works tends to be as dependent on their ‘social networks’ and standing.

What, then, do “serious” critics expect “serious” art to do, given that it is not to make money or to provide emotional comfort or culinary enjoyment? One answer to that (and I’m deriving this from the Adorno-driven art criticism in J.M. Bernstein’s book 'Against Voluptuous Bodies') might be that art brackets off a space in which our ways of thinking and experiencing and representing the world can be tested for their continued coherence and validity. Art allows for epistemological problems to be articulated, if not solved.Source: Empire of the senseless | Internal exileAnother related answer is that art holds open a space between experience and how it is conceptualized, seeming to manifest the otherwise indescribable, ineffable aspects of experience — the stuff that resists discursivity — and assures us that such a realm (the realm of freedom, if you believe Kant) really exists. If something can be completely described, then it is subject to full, mechanized determination; it can’t be free. Proper artworks can’t be fully described or “put to use” — they can’t be exhausted by critical discourse or ordinary consumption — so they reveal freedom to us. A critic’s work, from that perspective, succeeds by failing — when its strenuously efforts to describe a piece serve to reveal its inexhaustibility, its ability to renew its meanings from some impenetrable, possibly noumenal source.

An artwork itself embodies the same paradox: It may most succeed when it “eludes and fails visual and perceptual claiming,” as Bernstein puts it in describing a piece by Jeanette Christensen. A work’s “own power of proliferating discourse” is what it both “wants and refuses” because its significance ultimately depends on manifesting and holding open the gap between what there is and what can be described (or mediated, or simulated, or reproduced, or predictively generated), the gap between words and things, between the meanings we project onto things and “things in themselves.” That is, art can make palpable what Bernstein calls an “aporia of the sensible,” which makes it a reflection our experience of the crisis of modernity: the rationalizing disenchantment of the world, the scientistic instrumentalist mode of grasping reality, the commodification of experience under the pressures of capitalism, the “all that is solid melts into air” condition.

Running slow and short

There are books that have changed my life, but there are also podcast episodes. One example of this is Episode #787 of the Art of Manliness podcast, entitled Run Like a Pro (Even If You’re Slow). In it, Brett McKay talks with Matt Fitzgerald, a sports writer, a running coach, and the co-author of the book with the same name as the podcast episode.

The gist of the episode is that even shorter, slower runs help build fitness. And, in fact, this is what elite-level runners do. So these days I deliberately go for runs where my heart rate stays well below 140bpm. The upside for me is that it increases my ability to do my longer runs, faster.

This article in The New York Times backs this up with research showing the physiological and psychological benefits of runs of any length. See also this recent interview with Matt Fitzgerald.

Numerous long-term studies — some involving thousands of participants — have shown that running benefits people physically and mentally. Research has also found that runners tend to live longer and have a lower risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer than nonrunners.Source: Short Distance Runs Have Major Health Benefits | The New York TimesOne might assume that in order to reap the biggest rewards, you need to regularly run long distances, but there’s strong evidence linking even very short, occasional runs to significant health benefits, particularly when it comes to longevity and mental well-being.

[…]

The physiological benefits of running may be attributable to a group of molecules known as exerkines, so named because several of the body’s organ systems release them in response to exercise. While research on exerkines is relatively new, studies have linked them to reductions in harmful inflammation, the generation of new blood vessels and the regeneration of cellular mitochondria, said Dr. Lisa Chow, a professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota who has published research on exerkines.

Image: Unsplash

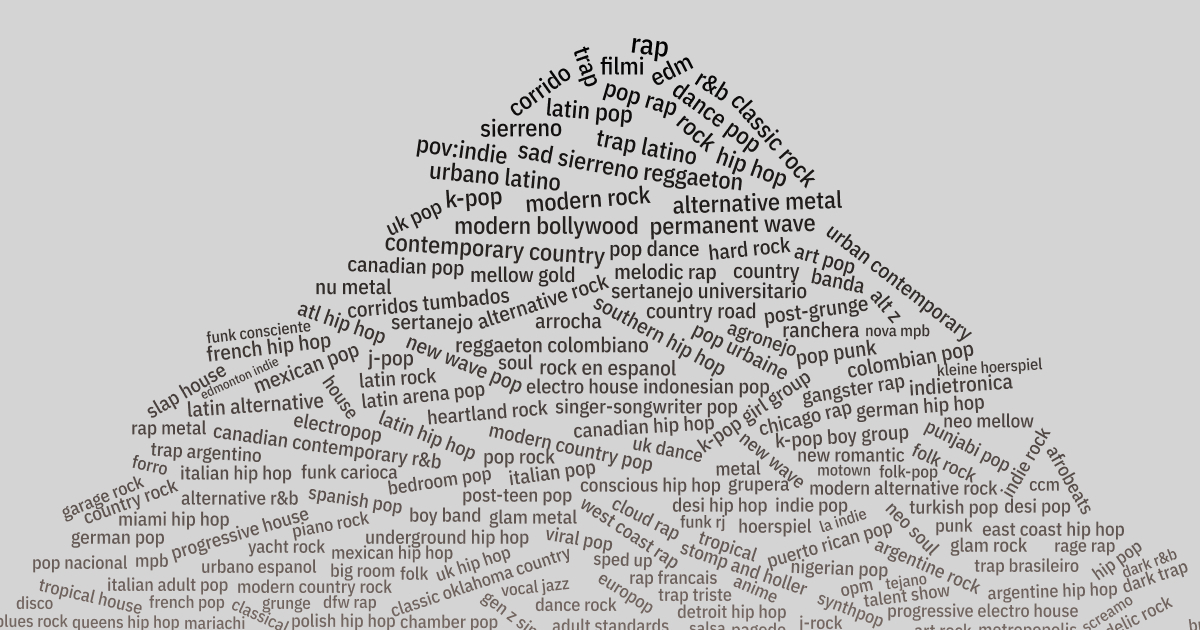

Dynamic ontologies and music genres

As a music lover and someone who has more than a passing interest in dynamic ontologies, I found this analysis of Spotify’s changing categorisation of genres fascinating.

Spotify Unwrapped shows users their most-streamed artists, tracks, and genres at the end of the year. But what if you want to find out at another time? I just had a look at Chosic, which told me that my main ‘parent genres’ are Hip hop, Pop, and Electronic. My top sub-genres are trip hop, downtempo, and electronica.

All of the pushback against genre classifications are valid, whether that's inventing escape room and stomp & holler of what qualifies as r&b vs. pop.Source: You should look at this chart about music genres | pudding.coolBut I still think an always-updating catalog of 6,000 genres is groundbreaking.

I see this effort in the same way I see taxonomy: technically accurate, colloquially useless.

For centuries we had generic names to identify animals, such as “fish.” Everything from squid to crabs (and obviously jellyfish) were lumped into the same “fish” bucket.

But on closer inspection, most of these animals were not related at all. In a research context, scientists have draw boundaries between animals that we mindlessly lumped together.

Similarly, the genre database adds much needed detail to broad categories, like hip hop and rock. For musicologists, it’s an anthropological gold mine. And for Spotify, it likely helps them to better profile their users' music tastes.

But these genres don’t necessarily work in casual conversation: you can describe your music taste as indie, even if, technically, Spotify says it’s escape room. The same goes for biology: people should call figs a fruit, even though it’s technically an inverted flower.

The social semi-permeable membrane

I never used LiveJournal, but I love Ben Werdmuller’s description of it as a place to journal in private with your friends. Although that’s not exactly what Substack provides, the interaction between the longer-form and the shorter form (through Substack Notes) is getting there.

It’s not as if it would be ideal to just have a place for existing friends, as you need new people and ideas to mix things up a bit. So it’s that semi-permeable membrane that makes things interesting: not quite fully public, but not quite fully private.

If you missed its heyday about twenty years ago, LiveJournal was a private blogging community that led to much of what we know as social media. You could follow your friends, and they could follow you back if they wanted; your posts could be shared with the whole world, just with your friends, or with a subset. Every post could host thriving, threaded discussions. You could theme your journal extensively, making it your own. And while you could post photos and other media, it was unapologetically optimized for long-form text. The fact that the whole codebase was also open sourced, paving the way for Dreamwidth and other downstream communities, didn’t hurt at all. Brad Fitzpatrick, its founder, went on to build a stunning number of important web building blocks.Source: Journaling in private with my friends | Ben Werdmuller[…]

Public social networks force us to use a different facet of our identities. In a private space with your friends, nobody really cares about your job, and nobody’s hustling to promote whatever it is they’re working on. Twitter nudged social networking into becoming a space for marketing and brands, which is a ball the new Twitter-a-likes have picked up and carried. Much like the characters from The Breakfast Club, each of the new Twitters has its own stereotypical niche: the nerds, the brands, the rich people, the journalists. But they all feel a little bit like people are trying to sell ideas to you all of the time.

Systems and interconnected disaster risks

When you see that humans have exceeded six of the nine boundaries which keep Earth habitable, it’s more than a bit worrying. But then when you follow it up with this United Nations report, it makes you want to do something about it.

I guess this is one of the reasons that I’m interested in Systems Thinking as an approach to helping us get out of this mess. I can imagine pivoting to work on this kind of thing, because (as far as I can see) everyone seems to think it’s someone else’s problem to solve.

Systems are all around us and closely connected to us. Water systems, food systems, transport systems, information systems, ecosystems and others: our world is made up of systems where the individual parts interact with one another. Over time, human activities have made these systems increasingly complex, be it through global supply chains, communication networks, international trade and more. As these interconnections get stronger, they offer opportunities for global cooperation and support, but also expose us to greater risks and unpleasant surprises, particularly when our own actions threaten to damage a system.Source: 2023 Executive Summary - Interconnected Disaster Risks | United Nations University - Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS)[…]

The six risk tipping points analysed in this report offer some key examples of the numerous risk tipping points we are approaching. If we look at the world as a whole, there are many more systems at risk that require our attention. Each system acts as a string in a safety net, keeping us from harm and supporting our societies. As the next system tips, another string is cut, increasing the overall pressure on the remaining systems to hold us up. Therefore, any attempt to reduce risk in these systems needs to acknowledge and understand these underlying interconnectivities. Actions that affect one system will likely have consequences on another, so we must avoid working in silos and instead look at the world as one connected system.

Luckily, we have a unique advantage of being able to see the danger ahead of us by recognizing the risk tipping points we are approaching. This provides us with the opportunity to make informed decisions and take decisive actions to avert the worst of these impacts, and perhaps even forge a new path towards a bright, sustainable and equitable future. By anticipating risk tipping points where the system will cease to function as expected, we can adjust the way the system functions accordingly or modify our expectations of what the system can deliver. In each case, however, avoiding the risk tipping point will require more than a single solution. We will need to integrate actions across sectors in unprecedented ways in order to address the complex set of root causes and drivers of risk and promote changes in established mindsets.

Image: DALL-E 3

System innovation is driven by reshaping relationships within the system

As I may have mentioned a little too often recently, I’m about to start an MSc in Systems Thinking. So I’m always on the lookout for useful resources relating to the topic.

I came across this one by Jennie Winhall and Charles Leadbeater from last year, which discusses how system innovation is driven by reshaping relationships within the system. It identifies four keys to system innovation: purpose, power, relationships, and resource flows. The focus is on relationships, which are the patterns of interactions between parts of a system. Transforming a system requires altering these relationships, which in turn unlocks other keys like purpose and power.

(Over a decade ago, I lined up to talk with Leadbeater after his talk at Online Educa Berlin. I was going to ask him something specific about his most recent book, but as everyone before him gushed over it, I think I just mumbled something about not liking it and then sloped off. Not my finest moment. Apologies, Charles, if by some reason you’re reading this!)

Systems are defined by the patterns of interactions between their parts: their relationships. Those interactions generate the outcomes of the system as a whole. Transforming the outcomes of a system requires remaking its relationships and then unlocking the other keys to system innovation: purpose, power and resources. This shift in relationships allows all those in the system to learn faster, to be more creative. System innovators redesign the relationships in the system to allow dramatically enhanced learning across the system, and thereby generate far better outcomes.Source: The Patterns of Possibility | The System Innovation Initiative

Tech typologisation

People love being typologised. I’m no different, although my result as an ‘Abstract Explorer’ in IBM’s Tech Type quiz wasn’t exactly a surprise.

Source: Tech Type Quiz | IBM SkillsBuildConsider this: a quiz to guide you to your unique fit for tech skills based on your strengths and interests. Find your future with this personalized assessment, bringing you one step closer to new skills to enhance your career in tech and key skills like artificial intelligence (AI). And it takes less than 5 minutes.

Is this the end of the 'extremely online' era?

As I mentioned in a recent post, you can’t win a war against system designed to destroy your attention. You have to try a different strategy. One of those is disengaging, which is what Thomas J Bevan is noticing, and advocating for, in this post.

I like his mention of going to a place where he noticed there was “something off” and he realised nobody was using their phone. Not because they weren’t allowed to, but because they were having too much of a good time to bother with them.

<img class=“alignnone size-full wp-image-8855” src=“https://thoughtshrapnel.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/DALL·E-2023-10-26-21.10.14-Vector-art-showing-a-massive-pile-of-smartphones-stacked-high-with-a-single-small-flower-growing-from-the-top-symbolising-hope-and-a-return-to-auth-1.png” alt=“Vector art showing a massive pile of smartphones stacked high, with a single, small flower growing from the top, symbolising hope and a return to authenticity.

" width=“1024” height=“1024” />

The consequences of life lived online have bled through into the real world and this has happened because we have allowed them to. It’s a cliché to say that real life is now a temporary reprieve from the online, as opposed to the other way around. We pay the price for all of this via boarded up shops, closing pubs, empty playgrounds and silent streets as each individual stays at home each night, enchanted by the blue flicker of their own little screen feeding them their own walled in world of news and content and edutainment.Source: The End of the Extremely Online Era | Thomas J BevanI believe it will end, this so-called way of life. Not through the Silicon Valley oligarchs spontaneously developing a conscience or being legislated into acting with a modicum less sociopathy. I don’t believe people will be frightened into changing how they act or suddenly shamed into putting their phones down for once in their lives. Such interventions don’t work with most addicts and more and more people are legitimately hooked on their devices than we are currently willing to countenance. No, I think this will all end, as T.S Eliot said, with a whimper. People will simply lose interest and walk away. Because the internet now is boring. People spend all day scrolling because they are trying to find what isn’t there anymore. The authenticity, the genuinely human moments, the fun.

Image: Created with DALL-E 3

Treating depression with hot yoga

Although I don’t think he went for the reasons given in this article, my late, great friend Dai Barnes used to love hot yoga. In fact, living as a teacher on-site at a boarding school, he’d travel miles to go to his nearest venue.

This Harvard Gazette article suggests that hot yoga might help with depression. I can definitely understand that: I’ve just re-added the spa to my leisure centre membership, and even just going in the sauna at this time of year feels incredible.

In a randomized controlled clinical trial of adults with moderate-to-severe depression, those who participated in heated yoga sessions experienced significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared with a control group.Source: Heated yoga may reduce depression in adults | Harvard Gazette[…]

In the eight-week trial, 80 participants were randomized into two groups: one that received 90-minute sessions of Bikram yoga practiced in a 105°F room and a second group that was placed on a waitlist (waitlist participants completed the yoga intervention after their waitlist period). A total of 33 participants in the yoga group and 32 in the waitlist group were included in the analysis.

[…]

After eight weeks, yoga participants had a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms than waitlisted participants, as assessed through what’s known as the clinician-rated Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-CR) scale.

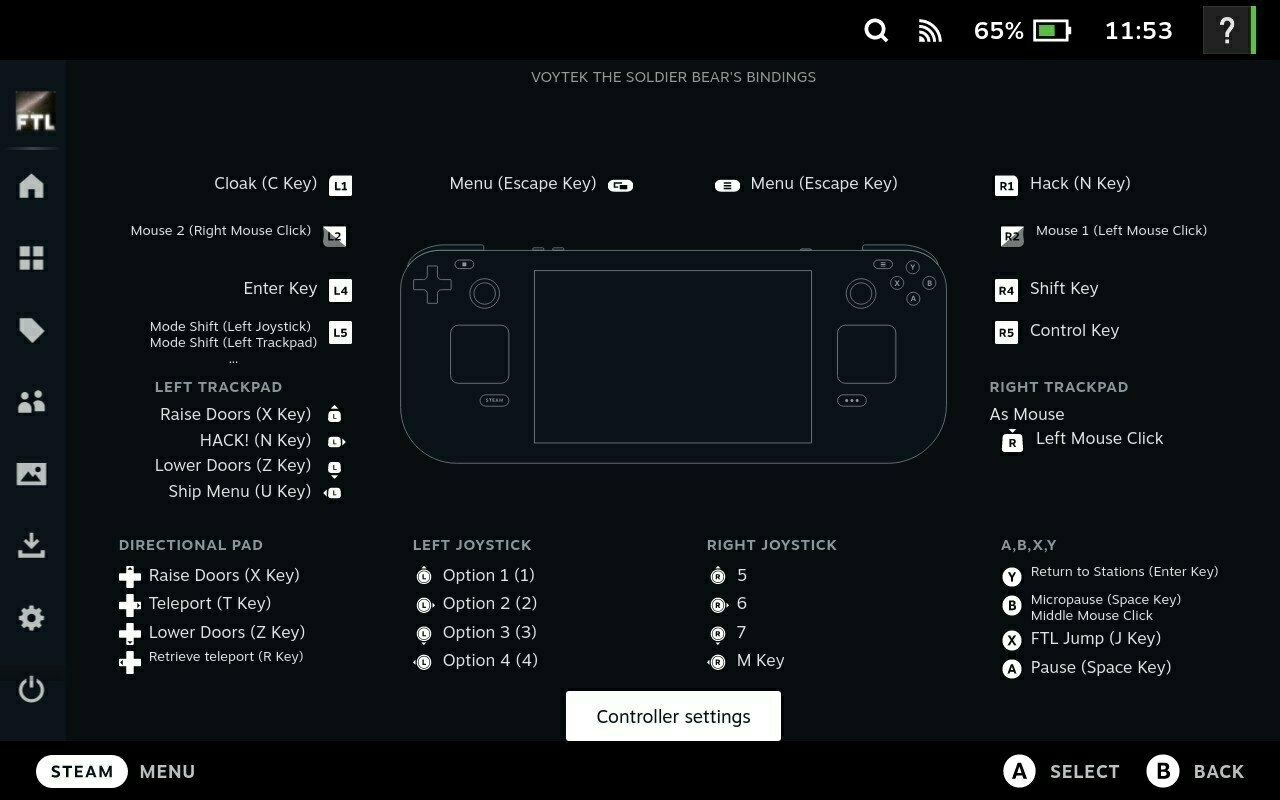

Why haven't you bought a Steam Deck yet?

I love my Steam Deck, and am so pleased that I not only bought it, but I bought the maxed-out version, despite the cost. This post goes into reasons why it’s so good.

Among other things, the author, Jonas Hietala, touches on the Steam library, sleep mode, and the fact that it’s an open platform. I think my favourite thing is its flexibility. It can even be used as a Linux desktop machine!

As I’ve said in other posts, I feel sorry for non-gamers. I get plenty of stuff done in my life, including parenting, and I’m a gamer. You’re missing out.

In the beginning of the year I gave myself a late Christmas gift and bought a Steam Deck for myself. There were two main reasons I decided to buy it:Source: The killer features of the Steam Deck | Jonas HietalaAnd boy did it deliver. The Deck is probably the most impressive thing I can remember buying since… I don’t know, maybe my first smartphone?

- I wanted my kids to play games instead of passively consuming endless amounts of YouTube.

- I wanted to combat my burnout and depression by picking up gaming again.