Substack bros

Having a moral compass can sometimes make life more difficult. I literally turned down a ridiculously well-paid gig last month because it contravened my ethical code. While that particular example was relatively clear cut, it’s more difficult when it comes to things like platforms which are used for free. At what point does your use of it become out of alignment with your values?

Twitter turning to X is a good example of this, with some people leaving a long time ago (🙋) while others, for some inexplicable reason, are still on there. I’d argue that the next service to be recognised as toxic is probably going to be Substack. I hosted Thought Shrapnel there briefly for a few weeks at the end of last year, but left when they started platforming Nazis. They seem to be at it again (here’s an archive version as that link was down at the time of writing).

While I wanted to give that context, this post is actually about a particular style of writing that is popular on Substack. I discovered this via Robin Sloan’s newsletter, which (thankfully) is written in a style at odds with the opposite of the advice given by Max Read, a relatively-successful Substacker. What Read says about being a “textual YouTuber” is spot-on. I can’t imagine anything more awful than watching video after video, but I will read and read until the proverbial cows come home.

The other thing which I think Read gets right is something I was discussing the other day (IRL I’m afraid, no link!) about how everyone wants Strong Opinions™ these days and to be the “main character.” My own writing these days is almost the opposite of that: slightly philosophical, with provisional opinions and, while introspective, not presenting myself as the hero of the story.

My standard joke about my job is that I am less a “writer” than I am a “textual YouTuber for Gen Xers and Elder Millennials who hate watching videos.” What I mean by this is that while what I do resembles journalistic writing in the specific, the actual job is in most ways closer to that of a YouTuber or a streamer or even a hang-out-type podcaster than it is to that of most types of working journalist. (The one exception being: Weekly op-ed columnist.) What most successful Substacks offer to subscribers is less a series of discrete and self-supporting pieces of writing–or, for that matter, a specific and tightly delimited subject or concept–and more a particular attitude or perspective, a set of passions and interests, and even an ongoing process of “thinking through,” to which subscribers are invited. This means you have to be pretty comfortable having a strong voice, offering relatively strong opinions, and just generally “being the main character” in your writing. And, indeed, all these qualities are more important than any kind of particular technical writing skill: Many of the world’s best (formal) writers are not comfortable with any of those things, while many of the world’s worst writers are extremely comfortable with them.

So, part of your job as a Substacker is is “producing words” and part of your job is “cultivating a persona for which people might have some kind of inexplicable affection or even respect.”

Source: Read Max

Image: Steve Johnson

Navigating the clash of identity and ability

I had a great walk and talk with my good friend Bryan Mathers yesterday. He made the trip up from London to Northumberland, where I live, and we went walking in the Simonside Hills and at Druridge Bay.

One of our many topics of conversation was the various seasons of life, including our kids leaving home, doing meaningful work, and social interaction.

Our generation is perhaps the first where men getting help through therapy is at least semi-normal, where it’s OK to talk about feelings, and where there’s the beginnings of an understanding that perhaps work shouldn’t define a man’s life.

What’s interesting about this article in The Guardian by Adrienne Matei is the framing as a “clash of identity and ability.” I’m already experiencing this on a physical level with my mind thinking I’m capable of running, swimming, and jumping much further than I’m able. It’s frustrating, but as the article points out, a nudge that I need to be thinking about my life differently as I approach 44 years old.

In 2023, researchers from the University of Michigan and the University of Alabama at Birmingham published a study exploring how hegemonic masculinity affects men’s approach to health and ageing. “Masculine identity upholds beliefs about masculine enactment,” the authors write, referring to the traits some men feel they must exhibit, including control, responsibility, strength and competitiveness. As men age, they are likely to feel pressure to remain self-reliant and avoid perceived weakness, including seeking medical help or acknowledging emerging challenges.

The study’s authors write that middle-aged men might try to fight ageing with disciplined health and fitness routines. But as they get older and those strategies become less successful, they have to rethink what it means to be “masculine”, or suffer poorer health outcomes. Accepting these identity shifts can be particularly difficult for men, who can exhibit less self-reflection and self-compassion than women.

[…]

[Dr Karen Skerrett, a psychotherapist and researcher] emphasizes there is no tidy, one size fits all way to navigate the clash of identity and ability: “There is just so much diversity that we can’t particularly predict how somebody is going to react to limitations,” she says.

However, in a 2021 research report she and her co-authors proposed six tasks to help people develop a “realistic, accommodating and hopeful” perception of the future: acknowledging and accepting the realities of ageing; normalizing angst about the future; active reminiscence; accommodating physical, cognitive and social changes; searching for new emotionally meaningful goals; and expanding one’s capacity to tolerate ambiguity. These tasks help people to recharacterize ageing as a transition that requires adaptability, growth and foresight, and to resist “premature foreclosure”, or the notion that their life stories have ended.

As we age, managing our own egos becomes a bigger psychological task, says Skerrett. We may not be able to do all the things we once enjoyed, but we can still ask ourselves how we can contribute and support others in meaningful ways. Focusing on internal growth and confronting hard truths with grace and clarity can ease confusion, shame and anger. Instead of clinging to lost identities, we can seek purpose in connection, legacy and gratitude.

Source: The Guardian

Smartphone bans are not the answer

After reading that “every parent should watch” a Channel 4 TV programme called Swiped: The School That Banned Smartphones I dutifully did so this afternoon. I’m off work, so need something to do after wrapping presents 😉

I thought it was poor, if I’m honest. As a former teacher and senior leader, and the father of two teenagers (one who has a real issue with screen time) I thought it was OK-ish as a conversation starter. But the blunt instrument of a ‘ban’, as is apparently going to happen in Australia, just seems a bit laughable to be honest. How are you supposed to develop digital literacies through non-use?

It’s easy to think that a problem you and other people are experiencing should be solved quickly and easily by someone else. In this case, the government. But this is a systemic issue, and not as easy as the government ‘forcing’ tech platforms to do something about it. What about the chronic underfunding of youth activities and child mental health services, and the slashing of council budgets? Smartphones aren’t the only reason kids sit in their rooms.

In March 2025, the Online Safety Act comes into force. The intention is welcome, but as with the Australian ‘ban’ it’s probably going to be hard to make it work.

The kids in the TV experiment were 12 years old. If, at the end of 2024, you’re letting your not-even-teenager on a smartphone without any safeguards, I’m afraid you’re doing it wrong. If you’re allowing kids of that age to have their phones in their bedroom overnight, you’re doing it wrong. That’s not something you need a ban to fix.

Smartphones, just like any technology, aren’t wholly positive or wholly negative. There are huge benefits and significant drawbacks to them. What’s more powerful in this situation are social norms. If this programme helps to start a conversation, then it’s done its job. I’m just concern that most people are going to take from it the message that “the government needs to sort this out.”

Source: Channel 4

Universities in the age of AI

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity are now an integral part of my workflow. This is true of almost everything I produce these days, including this post (I used this tool to create the image alt text).

I use genAI in client work, and also in my academic studies. It’s incredibly useful as a kind of ‘thought partner’ and particularly handy in doing a RAG analysis of essays in relation to assignments. Do I use it to fabricate the answers to assessed questions which I then submit as my own work? No, of course not.

This article in The Guardian reports from the frontlines of the struggle in universities for academic rigour and against cheating. Different institutions are approaching the issue differently, as you would expect. The answer, I would suggest, is something akin to Cambridge University’s AI-positive approach, outlined in the quoted text below.

The whole point of Higher Education is to allow students to reflect on themselves and the world. It’s been my experience that using genAI in appropriate ways is an incredibly enriching experience. Especially given that my Systems Thinking modules focus on me as a practitioner in relation to a specific situation in my life, what would it even mean to “cheat”?

I was notified this morning that I received a distinction for my latest module, as I did for the one before it. Would I have achieved those grades without using genAI? Maybe. Probably, even, given I’ve already got a doctorate. But the experience for me as a distance learner was so much better than being limited to interactions with my (excellent) tutor and fellow students in the online forum.

At the end of the day, I’m studying for my own benefit, and I know that studying with genAI is better than studying without it. I’m very much looking forward to using Google’s latest upgrade to Gemini Live for my next module, which I found recently to be very useful to conversationally prepare for interviews!

More than half of students now use generative AI to help with their assessments, according to a survey by the Higher Education Policy Institute, and about 5% of students admit using it to cheat. In November, Times Higher Education reported that, despite “patchy record keeping”, cases appeared to be soaring at Russell Group universities, some of which had reported a 15-fold increase in cheating. But confusion over how these tools should be used – if at all – has sown suspicion in institutions designed to be built on trust. Some believe that AI stands to revolutionise how people learn for the better, like a 24/7 personal tutor – Professor HAL, if you like. To others, it is an existential threat to the entire system of learning – a “plague upon education” as one op-ed for Inside Higher Ed put it – that stands to demolish the process of academic inquiry.

In the struggle to stuff the genie back in the bottle, universities have become locked in an escalating technological arms race, even turning to AI themselves to try to catch misconduct. Tutors are turning on students, students on each other and hardworking learners are being caught by the flak. It’s left many feeling pessimistic about the future of higher education. But is ChatGPT really the problem universities need to grapple with? Or is it something deeper?

[…]

What counts as cheating is determined, ultimately, by institutions and examiners. Many universities are already adapting their approach to assessment, penning “AI-positive” policies. At Cambridge University, for example, appropriate use of generative AI includes using it for an “overview of new concepts”, “as a collaborative coach”, or “supporting time management”. The university warns against over-reliance on these tools, which could limit a student’s ability to develop critical thinking skills. Some lecturers I spoke to said they felt that this sort of approach was helpful, but others said it was capitulating. One conveyed frustration that her university didn’t seem to be taking academic misconduct seriously any more; she had received a “whispered warning” that she was no longer to refer cases where AI was suspected to the central disciplinary board.

If anything, the AI cheating crisis has exposed how transactional the process of gaining a degree has become. Higher education is increasingly marketised; universities are cash-strapped, chasing customers at the expense of quality learning. Students, meanwhile, are labouring under financial pressures of their own, painfully aware that secure graduate careers are increasingly scarce. Just as the rise of essay mills coincided with the rapid expansion of higher education in the noughties, ChatGPT has struck at a time when a degree feels more devalued than ever.

Source: The Guardian

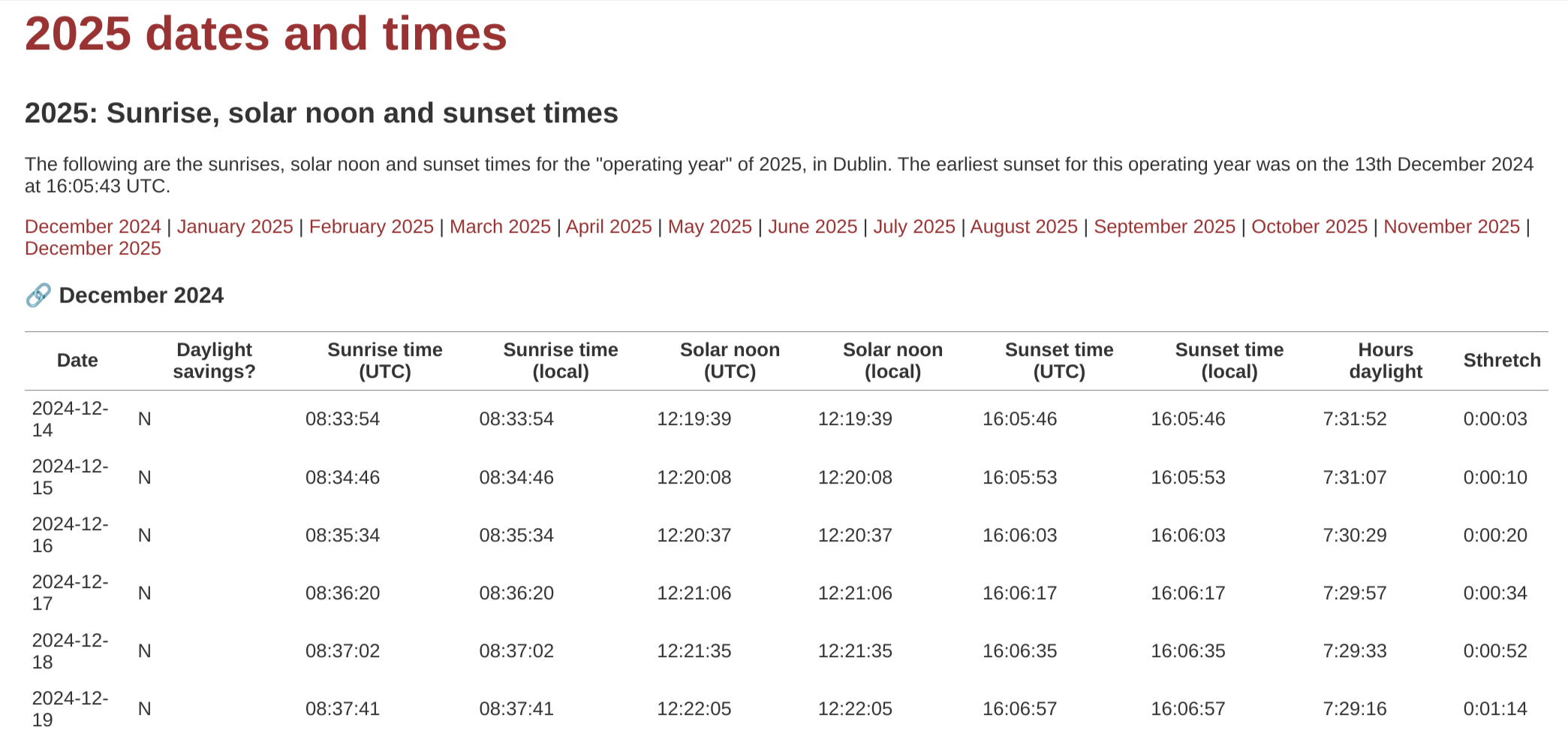

Sunrise, solar noon and sunset times for 2025 (in Dublin)

Most people probably have a favourite weather app. Mine is the oddly-named Weawow, for three reasons. First, it looks good; second, it allows you to choose the data source for weather forecasts; third, it shows sunrise, sunset, and ‘golden hour’ times in a really handy way.

I stumbled across a website today from Éibhear Ó hAnluain, a software engineer who lives in Dublin. Where I live is within 2 degrees latitude of there, so the timings are approximately correct for my location too. If someone knows a quick and easy way of generating a similar page for anywhere in the world, let me know!

Source: Éibhear/Gibiris

'Social' social networks?

I notice that Ev Williams, founder of Blogger, Twitter, and Medium, has co-founded a new social app called Mozi. It’s iOS-only for now, and seems to be reinventing some of the functionality of Foursquare check-ins with the private aspect of Path.

Path is the best social network I’ve ever used. I only used it with my family, but as I mentioned when lamenting its demise in 2018, it had the perfect mix of features. As I also hinted at in that post, for-profit private social networks just aren’t sustainable. We never did find anything to replace it, and Signal chats just aren’t the same.

Mozi seems to be based on people making travel plans and then serendipitously bumping into each other. I’d suggest this is already a solved problem for younger generations through Snap Maps, meaning it’s a firmly middle-aged problem. For that demographic, they’re probably likely to be travelling less. And if they’re British, a good proportion would pay money not to awkwardly bump into people they kind-of know 😅

Williams is a billionaire at this point, so he can do what he likes. But, inevitably, I’ll be pointing back to this post in less than two years when it shuts down. So I won’t be bothering to set up an account, even when it comes to Android.

When you spend your life building internet platforms, it’s hard to quit the habit. So while trying to get a grasp on the people I knew to invite to my birthday, I started thinking: What if we did have a network designed for this purpose? Not just invites, but a map of the people we actually knew and tools for enhancing those relationships?

In other words, what would an actually social network look like?

Clearly, it would need to be private. Non-performative. No public profiles. No public status competitions. No follower counts. No strangers.

Source: Medium

The lifehacked, minimalist life (and its discontents)

I used to be all about the life hacking when I was younger: optimising my time and ensuring maximum productivity was my goal. It made sense for that period of my life, as when I was in my twenties I was teaching full-time, pursuing a doctorate, and starting a family. Time seemed in short supply.

It wasn’t just me, though. There was very much what seemed a movement around this. Yes, it was mainly younger white men, but I admit to not realising that was the case at the time. This article by Laura Miller reflects on that time through the lens of a new book entitled Hacking Life: Systematized Living and Its Discontents. Ultimately, was it just about young men finding ways to do things that their mothers used to do for them? 🤔

The notion of hacking “life” arose during a period when technology was achieving one minor marvel after another, and “disruption” could still be touted as an unalloyed good. Yes, a tech bubble had burst at the beginning of the decade, but that was viewed as a failure of business models, not the tech itself… Smartphones seemed almost magical in their ability to iron the hassles and uncertainty out of everyday activities. You no longer had to give people directions to your house, rustle up a newspaper to find out where the movie you wanted to see was playing, or pick a restaurant with no idea what other diners thought about it.

[…]

As you’ve surely realized by now, it is possible to devote so much time to organizing your work that you never actually do any of it. As Reagle observes, several of the early champions of life hacking, include O’Brien and Mann, signed contracts to write books about how to defeat procrastination and attain Inbox Zero and then never got around to writing them. Most of them dropped out of the scene entirely, abandoning their blogs and denouncing the tech world’s preoccupation with productivity.

Others became proponents of minimalism, an ethos that involves getting rid of almost all of your stuff while becoming even more obsessed with the few things you keep. They sold their houses and moved into RVs. Like Marie Kondo on overdrive, they aimed to fit everything they owned into a single backpack.

[…]

Of course, plenty of people live in RVs and don’t own much because they have no other option; nobody asks them to give TED talks about it. Reagle points out that minimalism has been a phenomenon of young, educated, affluent white men supposedly repudiating a middle-class materialism made possible by their careers in the tech industry and lack of family encumbrances. “Minimalism is for well-off bachelors,” as Reagle puts it, and not especially imaginative ones at that. If you make your fortune at 30 and you’re the sort of person who’s never given much thought to a purpose beyond “success,” what do you do with yourself? A common and strikingly unimaginative answer among minimalists was full-time travel. The possibility that experiences can be accumulated and consumed in just as mindless a fashion as belongings can did not occur to them.

[…]

As one anonymous wag has observed, the vast resources of Silicon Valley have too often been applied to the problem of “what is my mother no longer doing for me?” Don’t get me wrong: I remain in the market for solid, practical tips. But life, like a palm tree or any other organic thing, can only take so much hacking before it collapses.

Source: Slate

Hierarchies should be fluid and temporary

Last week, I shared a post from this same website, an ‘advent calendar’ of blogging where people reflect what they’ve thought a lot about over the last year.

This entry is about comfort zones and systems change. The author makes their living in ‘systems change’ and points out that it’s natural for things to evolve and change over time. Not to allow this to happen privileges the few over the many. It’s a good way of thinking about it.

I’ve included an image that Bryan Mathers made for our co-op last year to illustrate my anti-establishment tendencies. I’m almost embarrassed for other people when they use the phrase “My boss said…” as if it’s a normal thing. Any hierarchies should be fluid and temporary.

On the surface, it can seem like people’s resistance to making things better is down to their fear of the unknown, and they lean into the idea of ‘better the devil you know’. However, I’m eight years into this gig, and actually, what I’ve observed is that it’s the complexity that comes with imagining the world anew that people don’t like.

[…]

They find it destabilising when new ways of being emerge because – in order to adopt them – it would mean straying from a well-trodden route. New ideas threaten to force people to create new pathways, adapting to unfamiliar scenarios as they go.

The reality, though, is that this is how life works. We can manufacture fixed systems that seek to impose rigid structures – for example, hierarchies, competition and individualism have all been created. But, at its core, the world shifts and alters and adapts. You only have to look at the natural world to see how life constantly evolves, or the universe to recognise we’re constantly expanding.

By resisting change, we are upholding the manufactured systems that we are forced to live within. The same systems that are rigged against us.

Because those systems are familiar. They are societal norms. They are known.

As long as we are resistant to change, we allow power to be consolidated in the hands of a dominant few who get to shape the media, government and organisations which prescribe how we live our lives.

Source: I thought about that a lot

Image: CC BY-NC Visual Thinkery for WAO

Anxiety as an expensive habit

I’m not sure if this post by Ryan Holiday is just a form of (not-so) subtle marketing for his ‘Anxiety Medallion’ but he nevertheless makes some good points. Framing anxiety as his “most expensive habit,” Holiday talks about what anxiety “steals” from us.

Without wanting to wade too much into the nature vs nurture debate, I think it’s clear that genetics provides some kind of baseline level here. For me, that’s both incredibly frustrating (you can’t choose your ancestors!) but also somewhat liberating. I can’t remember where I learned to do so, but over the last 18 months or so I’ve started saying to myself “it’s all just chemicals in my brain.”

It doesn’t always work, of course, but along with good exercise and sleep routines — and ensuring my stress levels remain low — I manage to cope with it all. The hardest thing to explain to people is that anxiety doesn’t have to have an object. Existential angst, for example, isn’t just something that 19th century philosophers suffered from, but regular people in the here and now.

It’s not flashy, it’s not thrilling, and it doesn’t even provide the fleeting pleasures that other vices might. And yet, anxiety is a vice. A habit. A relentless one that eats away at your time, your relationships, and your moments of joy.

[…]

Seneca tells us we suffer more in imagination than in reality. Anxiety turns the hypothetical into the actual. It drags us into a future that doesn’t yet exist and forces us to live out every worst-case scenario in vivid detail. The cost isn’t just mental. It’s physical. It’s emotional. It’s relational.

[…]

Anxiety is expensive—not just in terms of the mental toll, but in the way it costs us our lives. Every minute spent consumed by worry is a minute lost.

Source: Ryan Holiday

Image: Nik

Yeah, but how?

I listen to a popular podcast called The Rest is Politics. I remember listening before the US Presidential Election where the hosts could not bring themselves to believe that Trump would successfully win a second term. Why? Because he has “no ground game.” That is to say, he doesn’t have the processes set up to be able to mass-mobilise supporters to knock on doors, get the word out, and encourage people to vote.

Given the results, that’s increasingly looking like 20th century thinking. I’ve heard anecodotes of people knocking on doors and people already having talking points from following social media influencers and watching YouTube videos. If people have already made up their mind based on things they’ve seen on the small screen they carry around with them everywhere, knocking on their door every few years isn’t going to change their mind.

This is why social media is so important. This post argues that we need to be creating new spaces, not just “meeting people where they are.” It’s not an incorrect position to take. I don’t disagree with anything in the post. But how exactly? Mastodon and the Fediverse more generally could have been the ‘ark’ to which people fled after leaving X/Twitter. Instead, they flocked to another “potentially decentralised” social network, with investors and no incentive to do anything other than what everyone else has done before.

I’d like to organise. I’d like to use Open Source software everywhere. I’d like to only buy things from co-ops. However, back in the real world where I need to interact with capitalism to survive…

It’s hard to ignore the fact that progressive movements, despite their critical rhetoric, rely on the same capitalist and surveillance-driven platforms that actively subvert their goals. Platforms like Google, Facebook, The Communication Silo Formerly Named Twitter, and Instagram—behemoths of surveillance capitalism—become the very spaces where activism happens. These corporations profit from our clicks, likes, and shares, capturing our data and feeding it into systems of control that profit from inequality, exploitation, and surveillance.

This ongoing reliance on corporate-owned platforms represents a deep contradiction in our movements. By using these tools, we are feeding the beast—the tech giants profiting from our data, monetizing our activism, and undermining the very causes we fight for. In a real sense, we’ve become complicit in our own subjugation, ceding our autonomy, values, and privacy to the very corporations that reinforce the inequalities we seek to dismantle.

[…]

The phrase “you have to meet people where they live” has been an all-too-convenient defense for this complicity. But this outlook only reinforces the status quo. Shouldn’t a genuinely radical movement—especially a socialist one—work toward building new spaces where people can live, organize, and act outside of these exploitative systems?

Socialist movements throughout history didn’t merely meet people in existing power structures—they created new models of organization, new forms of cooperation, and new spaces for living and working together. From cooperatives to unions, the goal has always been to build alternatives to the capitalist way of life. Why, then, should we treat digital space any differently?

[…]

We cannot keep organizing through the tools of surveillance capitalism if we want to build a post-capitalist future. We must take control of the infrastructure itself—through open-source, community-run platforms. This is not just about technical solutions, but about aligning our methods of organizing with our values and principles.

Source: Seize the Means of Community

Image: Intricate Explorer

Anti-anti-AI sentiment

I discovered this article via Laura who referenced it during our co-working session as we updated AILiteracy.fyi. As a fellow Garbage Day subscriber, she’d assumed I’d already seen it mentioned in that newsletter. I hadn’t.

What I like about this piece from Casey Newton is how he points out how disingenuous much of anti-AI sentiment is. There are people doing important, nuanced work pointing out the bullshit (hi, Audrey) but there’s also some really ill-informed, clickbaity stuff that reinforces prejudice.

Of course people will use generative AI to cheat. Of course they will use it to create awful things. But what’s new there? A lot of the hand-wringing I see is from people who have evidently never used an LLM for more than five seconds. They would have been the same people warning about the “dangers” of the internet in the late 90s because “anyone can create a website and put anything online!”

The thing is, while we can’t guarantee that any individual response from a chatbot will be honest or helpful, it’s inarguable that they are much more honest and more helpful today than they were two years ago. It’s also inarguable that hundreds of millions of people are already using them, and that millions are paying to use them.

The truth is that there are no guarantees in tech. Does Google guarantee that its search engine is honest, helpful, and harmless? Does X guarantee that its posts are? Does Facebook guarantee that its network is?

Most people know these systems are flawed, and adjust their expectations and usage accordingly. The “AI is fake and sucks” crowd is hyper-fixated on the things it can’t do — count the number of r’s in strawberry, figure out that the Onion was joking when it told us to eat rocks — and weirdly uninterested in the things it can.

[…]

Ultimately, both the “fake and sucks” and “real and dangerous” crowds agree that AI could go really, really badly. To stop that from happening though, the “fake and sucks” crowd needs to accept that AI is already more capable and more embedded in our systems than they currently admit. And while it’s fine to wish that the scaling laws do break, and give us all more time to adapt to what AI will bring, all of us would do well to spend some time planning for a world where they don’t.

Source: Platformer

The trials and tribulations of working openly

This advent series is published anonymously, but Matt Jukes outed himself as the author of this one. It makes sense him doing so, as it’s about working in the open, and how it’s benefited him — but now he feels like it’s time to “shut up.” For what it’s worth, I hope he doesn’t.

I’m sharing it here, though, as there are plenty of people who I know who share as openly as Jukesie, and who might be thinking about different seasons to their careers. I suppose I’m one of them. My wife has never been comfortable about my ‘oversharing’, especially in the early days of Twitter. That’s why I’ve toned down that aspect a bit over the years

There’s something about oversharing that feels like a focus on the self. But, as I was explaining to my daughter in relation to art just yesterday, you have to find the thing that allows you to represent yourself in the world. For me, it’s writing. For others it’s drawing, painting, or singing. Without that, it’s a sad, unexpressed life.

(It’s also well worth looking at the other essays in the series, as there’s some really good writing here.)

People I’ve never met in person are familiar with my ups and downs at work, my health, my travels and my ambitions. My openness has been called brave, inspiring, narcissistic and irritating. It’s provided me with an army of acquaintances around the world, but probably no more close friends than if I’d never popped my head above the parapet and uttered (or written) a word.

I wear my commitment to working in the open as a badge of honour and have spent years advocating for others to follow suit.

The problem though, and the reason I’ve been thinking a lot about it, is that I am tired of it and really feel like it is time to shut up. I don’t know whether those peak Covid years rewired something in my head, or whether it is just a by-product of getting older, but the energy required to maintain quite so public a persona has become unsustainable, and increasingly less enjoyable. The challenge though, is that my professional identity is so entangled in my openness, I fear what would happen if I did quiet down.

This fear is my own fault. My career has become a patchwork of short-term jobs, generated by a short attention span, and held together by a loose theme and a high profile. If the profile declines, will it all tumble down like a house of cards?

Source: I thought about that a lot

Captive user bases are ripe for enshittified services

I missed this when he published it last year, but this strongly-worded and reasoned stuff from Cory Doctorow still applies. He explains why he’ll only ever be found on actually federated social networks. The word he coined, enshittification, can only applied to a captive user base. It makes me think about what I’m doing on Bluesky — which I’ve already described a ‘pound shop Mastodon’.

Look, I’m done. I poured years and endless hours into establishing myself on walled garden services administered with varying degrees of competence and benevolence, only to have those services use my own sunk costs to trap me within their silos even as they siphoned value from my side of the ledger to their own.

[…]

Being a moral actor lies not merely in making the right choice in the moment, but in anticipating the times when you may choose poorly in future, and taking steps to head that off.

[…]

That’s where Ulysses Pacts come in. […] We make little Ulysses Pacts all the time. If you go on a diet and throw away your Oreos, that’s a Ulysses Pact. You’re not betting that you’ll be strong enough to resist their siren song when your body is craving easily available calories; rather, you are being humble enough to recognize your own weakness, and strong enough to take a step to protect yourself from it.

[…]

I have learned my lesson. I have no plans to ever again put effort or energy into establishing myself on an unfederated service. From now on, I will put more weight on how easy it is to leave a service than on what I get from staying. A bad service that you can easily switch away from is incentivized to improve, and if the incentive fails, you can leave.

Source: Pluralistic

Pleias: a family of fully open small AI language models

I haven’t had a chance to use it yet, but this is more like it! Local models that are not only lighter in terms of environmental impact, but are trained on permissively-licensed data.

Training large language models required copyrighted data until it did not. Today we release Pleias 1.0 models, a family of fully open small language models. Pleias 1.0 models include three base models: 350M, 1.2B, and 3B parameters. They feature two specialized models for knowledge retrieval with unprecedented performance for their size on multilingual Retrieval-Augmented Generation, Pleias-Pico (350M parameters) and Pleias-Nano (1.2B parameters).

These represent the first ever models trained exclusively on open data, meaning data that are either non-copyrighted or are published under a permissible license. These are the first fully EU AI Act compliant models. In fact, Pleias sets a new standard for safety and openness.

Our models are:

- multilingual, offering strong support for multiple European languages

- safe, showing the lowest results on the toxicity benchmark

- performant for key tasks, such as knowledge retrieval

- able to run efficiently on consumer-grade hardware locally (CPU-only, without quantisation)

[…]

We are moving away from the standard format of web archives. Instead, we use our new dataset composed of uncopyrighted and permissibly licensed data, Common Corpus. To create this dataset, we had to develop an extensive range of tools to collect, to generate, and to process pretraining.

Source: Hugging Face

Image: David Man & Tristan Ferne

AI Literacies are plural

I see a lot of AI Literacy frameworks at the moment. Like this one. From my perspective, most of them make similar mistakes, thinking in terms of defined ‘levels’ using some kind of remix of Bloom’s Taxonomy. There’s also an over-emphasis on cognitive aspects such as ‘understanding’ while more community and civic-minded aspects are often under-emphasised.

So if you think that I’m ego-posting this page, created by Angela Gunder for Opened Culture, then you’d be correct. I met Angela for the first time via video conference a few weeks ago after she sent me an email telling me how she’d been using my work for years. We’ve had a couple more chats since and I’m hoping we’ll get to work together in the coming months.

Recently, Angela has been doing work for UNESCO, as well as on an MIT/Hewlett Foundation funded project. For both, she used my Essential Elements of Digital Literacies as a frame, understanding literacies as plural and contextual. WAO is currently working on an update to ailiteracy.fyi so more on all of this in the new year.

The Dimensions of AI Literacies were developed to address the growing need for educators, learners, and leaders to navigate the complexities of AI in education. Remixed from the work of Doug Belshaw’s Essential Elements of Digital Literacies, this approach recognizes that AI literacies are not a binary of literacy vs. illiteracy, but rather consist of a diverse and interconnected set of competencies. By considering AI literacies as a plurality, this taxonomy enables a deeper understanding of how AI can be leveraged to improve the impact of teaching and learning across various sociocultural contexts. This view helps educators design inclusive and adaptive learning experiences, allows learners to engage with AI tools critically and creatively, and empowers leaders to foster responsible and impactful AI integration across their institutions. Additionally, as AI tools and systems continue to expand in quantity and ability, this taxonomy gives strategists and practitioners a flexible vocabulary to use in navigating the rapidly evolving landscape of AI in education. Through these dimensions, educators and leaders are provided with a foundation for building a collaborative and reflective discourse on AI use, encouraging the development of skills that will shape the future of education in meaningful and impactful ways.

I hope someday soon I can visit your website

When I worked at the Mozilla Foundation a decade ago, there was a programme called Webmaker. There were web apps and Open Source tools that the team created to help people learn how the web works in a practical, hands-on way. My work on web literacy and Open Badges underpinned it (see this white paper for example) with the aim to avoid ‘elegant consumption’.

In this post Gita Jackson points out that elegant consumption via centralised, Big Tech-owned social networks has won the day. The way to resist that is to build your own website. Learning some code is great, but these days Mozilla has a service called Solo which makes it super-easy to have your own website. There are easy ways to run your own blog. It takes more effort, but it’s worth it.

Social media erased the need to build a website to express yourself online. Sure, early social media like MySpace allowed for you to radically change the look and feel of your page—adding music and changing the background—but ultimately, it was still a MySpace page, with a comment wall and your top eight friends. On top of that, MySpace had total ownership of that page, meaning when the site was bought and sold, individual users had no say in the changes. By 2019, you couldn’t even look at your old MySpace accounts anymore because they lost all the data from prior to 2016.

This only accelerated as we moved to new social media, like Facebook, which was determined to keep all important contact information within the app. Instead of a local business making a website on Geocities, they would make themselves a Facebook page—or now, an Instagram account—because all their customers likely had Facebook accounts already.

[…]

It is clear that tech billionaires like Musk know that when they own the means of communication, they run the whole show. If you’ve made a home on Twitter, you’re basically completely vulnerable to Musk’s randomly changing whims, and also his disgusting political beliefs. He campaigned with Trump and immediately congratulated him when he won the election. Also congratulating the President-elect were Zuckerberg and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, two tech oligarchs who also want us to use their proprietary apps and websites for everything in our lives.

[…]

To me, having my own website, even one I run as a business with my friends, gives me a degree of freedom over my own work that I’ve never had before. If you look at my work on Kotaku, there’s so many garbage ads on the screen you can barely see the words. Waypoint and Motherboard are both being run like a haunted ship, pumping out junk so that Vice’s new owners can put ads on it. I don’t have to worry about that anymore—I don’t have to worry about my work being taken down or modified or sold, or put in an AI training set against my will. I have my own website, and it is mine, and I get to own it completely. I hope someday soon I can visit your website.

Source: Aftermath

Image: Patrick Tomasso

Should health tech be used to inform health professionals?

There are risks with any kind of increased information or data presented to people without the kind of background to understand it. That’s why we have professionals.

There’s also a concern about privacy and data getting into the wrong hands. That’s why we have safeguards.

But, on the other hand, when it comes to smart watches and other health monitoring devices, we’re talking about trying to better understand our own bodies. I’ve got a Garmin smart watch which I use in conjunction with the Garmin app and also with Strava. You’ll pry it from my cold, dead hands

There was one time when I went to the hospital and the consultant was interested in what my watch had been telling me. But, as this article shows, that’s rare.

What we need is some kind of standard way of reporting this data, along with caveats about how it was collected and how much it can be trusted.

Health Secretary Wes Streeting has talked about a proposal to give wearables to millions of NHS patients in England, enabling them to track symptoms such as reactions to cancer treatments, from home.

But many doctors – and tech experts – remain cautious about using health data captured by wearables.

I’m currently trying out a smart ring from the firm Ultrahuman – and it seemed to know that I was getting sick before I did.

It alerted me one weekend that my temperature was slightly elevated, and my sleep had been restless. It warned me that this could be a sign I was coming down with something.

I tutted something about the symptoms of perimenopause and ignored it - but two days later I was laid up in bed with gastric flu.

Source: BBC News

The UK needs a wealth tax

Polly Toynbee, writing in The Guardian, argues that we need a wealth tax in the UK. In my opinion, it’s massively overdue. The only people who have benefited from the financial crisis and Brexit are those who were already well-off.

Given that you don’t get to choose how wealthy your parents are, advantages that you get in life from their wealth are a massive impediment to social mobility. Obviously.

Over the next 30 years, an unprecedented avalanche of £5.5tn will land in the laps of those who have chosen their parents wisely. The inheritocracy is ascending into the stratosphere: asset-rich parents are buying homes and advantage for their children and their children’s children, securing ever-rising privilege. Those born in the 1980s are on average due inheritances worth twice as much as those born in the 1960s. Parental income and wealth is a stronger predictor of someone’s lifetime earnings and wealth than in generations before. Inheritance is becoming an obstacle to social mobility.

No politician concerned about inequality, fair opportunities or financing the public realm can ignore wealth any longer. While wages have stagnated for 16 years, wealth has accelerated. Traditionally, policymakers have focused on fairness of incomes. But today, the possession of wealth is proving the greater distortion, with so much of it in effect untaxed. The mantra for a long time was that wealth taxes don’t work. But that can no longer be the answer.

[…]

If Labour wants to achieve things in power, it’s clear it needs more money. Wealth is the place to look.

Source: The Guardian

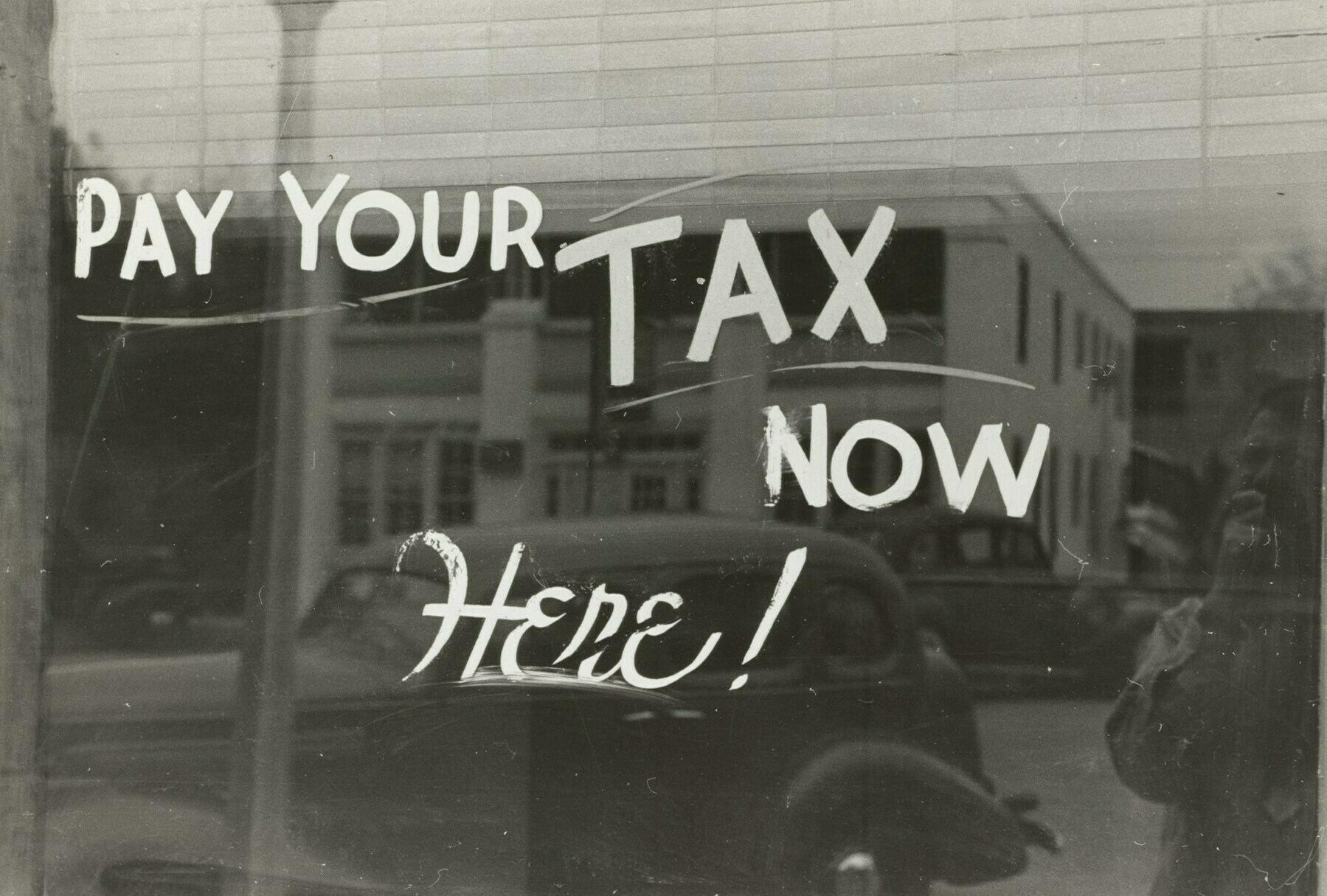

Image: The New York Public Library

Self-hosting isn't a thing for regular people

Perhaps I’m just getting old, but this rant resonated with me. Ostensibly, it’s about a particular app shutting down, but I’m quoting the bit more generally about ‘self-hosting’ not being an option for people who do things other than spend every waking moment near a computer.

If there’s one thing I don’t want to be in my forties it’s a system administrator. As time moves on, we abstract away from complexity to provide things as a service, which as far as I’m concerned is exactly as it should be.

One of the other options Omniverse suggests for moving off of its service is self-hosting, which is akin to telling me to go fuck myself. Self-hosting is great if your hobby is self-hosting things. Mine is not. My hobbies are reading things and drawing things and sewing things and climbing up things and feeling guilty about not writing enough things. I very much appreciate that I know how to computer well enough that I could self-host if I had to, could go fork some abandoned Obsidian plugin that hasn’t been updated in 3 years to try and make yet another rotting part of my digital ecosystem rot a little bit less slowly, but that is a terrible use of my time. I already host my own Fediverse server, if by host you mean pay someone in Europe a bunch of money to host it for me and all I have to do is ban some assholes occasionally, because at the moment I have more money than I have time and I simply do not wish to spend my one wild and precious life learning how to configure goddamn Sidekiq to optimize background processing queues just so I can offer my friends a refuge from the dillweed who turned Twitter into a Nazi bar.

Also, you know what people never talk about when they talk about self-hosting? A succession plan. If I suddenly died I don’t have any provisions for making sure the people relying on my little Hometown server aren’t suddenly left up a creek without a paddle. I am not going to host a read-later service just for myself because that would be an incredibly inefficient use of time and resources even if I did have the time and inclination to do so, but I am also not going to host anything else for my friends until I figure out what contingency plans look like. It’s on my list of things to figure out for my will, which is a very long list. This long list sits on another very long list of life TODOs that I never seem to get around to. I have wanted to figure out my will for approximately eight years, and I know that because that is how long ago I got married and we were like “ha ha we should do that soon” and then simply never did. Because life is so complicated, my guy.

Source: The Roof is on Phire

Image: Christopher Gower

On 'billionarism'

This is a long-ish post, the second half of which discusses Bluesky. However, I’m more interested in the first half which talks about the ‘billionarism’ ideology which seems to have infected the world. It’s an anti-civic attitude which captures human value as financial value, and sees contributing to society as a ‘cost’.

Well kids, we live in a world built for billionaires and narcissists, and we pretty much have our whole lives. I know this isn’t news to people of awareness such as yourselves, but the proof is in the pudding now, and the pudding is on fire.

[…]

A “billionaire” is somebody who infects themselves daily with the sick need to amass so much money that they no longer are constrained by societal demands and expectations, but rather are able to impose their own demands and expectations upon society. A billionaire utilizes this power in order to modify society so that even more money comes to them, leaving them even further above the demands and expectations of society, allowing them to impose their will over society to an even greater extent, and so on and so forth. It’s a grave sickness, billionairism—a self-inflicted one, I think I mentioned—and what’s worse is that it’s a sickness whose worst symptoms billionaires force the rest of us to suffer. That’s the first way that billionairism resembles narcissism.

And we should talk about what billionaires do. What they do is get themselves in proximity to the natural value generated by our natural human system—value created by humans simply by being human and living together in proximity to one another, the structure known as “society,” in other words, from which all possible value springs—and then steal it for themselves and only themselves. They capture certain parts of natural generative human value—some human enterprise or process or concept, something other that has been made possible only through the existence of human society, and has only become successful within that context by generating value for other humans—and use their unnaturally stolen value to own it, and then pervert it so that it increasingly stops providing value to others but only sends value to themselves. They then use the stolen value that they have hoarded all for themselves as proof that they are exceptionally valuable people. Meanwhile, there is a certain amount of that stolen value that they still have to give back in order to keep the mechanism of their theft going—an amount that they call “cost,” which they greatly resent—which they use as proof that they are the beneficent source of all value anyone receives.

[…]

It occurs to me that nothing damages billionaires and other narcissists like human community, which is probably why they work so hard to destroy it.

Source: The Reframe

Image: Jp Valery