Thinking in systems means to think in boundaries, not binaries

I haven’t yet been able to apply my studies last year on systems thinking to my work as much as I’d hope. I remain interested in the topic, however, and this piece in particular.

It was recommended in Patrick Tanguay’s always-excellent Sentiers newsletter. As Patrick points out, it includes some great minimalistic animations, one of which I’ve included above.

It’s the backside of any notion of holistic, interconnected, interwoven networks that often get associated with the overused tag line of “Systems Thinking”. It acknowledges that in order to make sense we are bound to draw a boundary, a distinction of what we mean / look at / prioritise – and all the rest. Only through its boundary a system genuinely becomes what it is. It marks the difference between a system and its environment. And with that boundaries are inherently paradoxical: they create interdependency precisely by drawing a line:

They are interfaces.

What follows is a framework for moving within and beyond binaries in five steps:① Affirmation → ② Objection → ③ Integration → ④ Negation → ⑤ Contextualisation.

This is not a linear path but a cycle, a tool for keeping in motion while acknowledging the gaps along the way.

[…]

In a world of contexts, there is no way for any one actor – be it a planner, a city, or a government – to account for the many contexts they are acting in. Here, we are forced to think and act in constellations ourselves: in networks of mutual and collective contextualisation, of pointing out each others blindspots (the contexts we didn’t know we didn’t see), of taking parts of this complexity and leaving other parts to others.

This is very close to notions of intersectionality, the simultaneousness of difference and the possibility of many things being true at the same time. It also makes our understanding of an intervention or position very interesting - which now becomes a literal intersection, a specific constellation of multiple positions across a system of differences.

Source & animation: Permutations

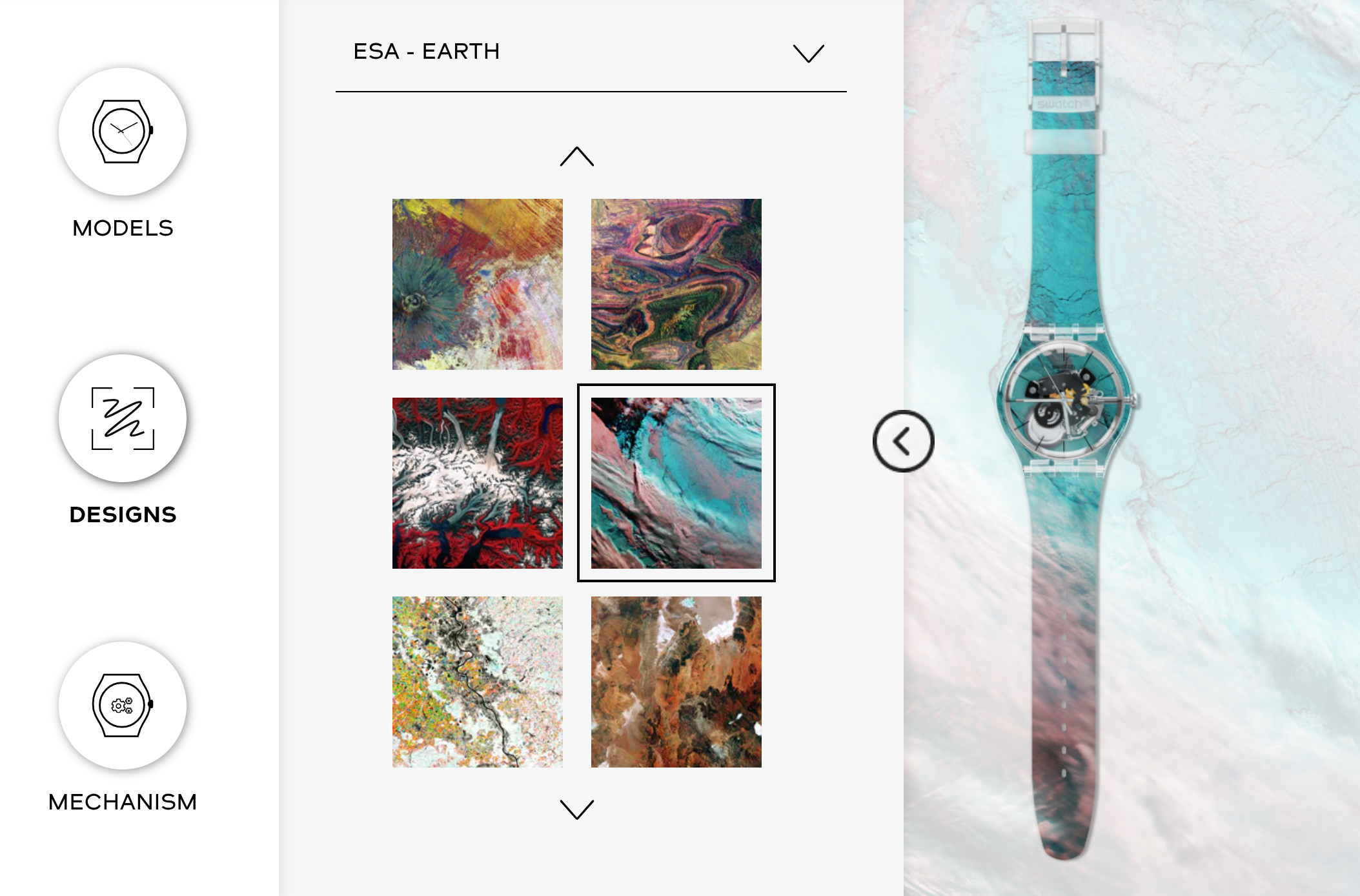

Swatchy!

Warren Ellis posted about a ‘Metropolis’ style Swatch watch, which led me down a rabbithole which ended with me learning that you can make contactless NFC payments with some of the newer models. Also, you can customise them in cool ways.

I mean, you know you’re a middle-aged guy living in the west when you have more pairs of trainers than your wife does shoes, and you start thinking about what your watch is saying about you. Oh, and the retro computing vibe, did I mention that?

It’s rare I see a Swatch that I would want to wear, but I tripped over this, found in this article, and I am mildly obsessed. It’s from 1989, and I’m fascinated by its Bauhaus-y, METROPOLIS the film-y look. And, let’s face it, a very 80s look. But the cool European 80s.

Source: Warren Ellis / Swatch

A systemic scramble through digital shadows

I’m tired. It’s partly the calcium channel blockers I’m on, and partly that I haven’t had any days of holiday so far this year. As a result, I’ve decided to take a week off posting my regulation 10 posts here at Thought Shrapnel.

While I thought about just posting the links (see below) I thought it would be interesting to instead perform a bit of an experiment.

- By Default, Signal Doesn’t Recall (Signal blog)

- How Social Reactionaries Exploit Economic Nostalgia (Jacobin)

- MCP is the coming of Web 2.0 2.0 (Anil Dash)

- Dispatch for the week ending 18 May 2025 (Adam Greenfield)

- The RSA Badge Standard (RSA)

- Experts have it easy (Boyd Kane)

- Insurance for AI: Easier Said than Done

- My Dream Fediverse Platform (Sean Tilley)

- Aligning LLM Choice to Your Use Case: An Expert’s Guide (Oblivus Blog)

- Powering Planes with Microwaves Is Not The Craziest Idea (IEEE Spectrum)

If you prefer, I copy/pasted the links into Perplexity, gave it a few instructions, and it spat out this summary “in the style of Doug Belshaw.” I’m not quite sure what to make of it; I mean, I don’t disagree with any of this (especially the last paragraph) but it’s not quite how I would express it…

The convergence of these ten articles reveals something I’ve been thinking about for years: we’re at a moment where digital infrastructure is being rebuilt from the ground up, and the choices we make now will determine whether technology serves human agency or constrains it. Signal’s anti-Recall features perfectly illustrate this tension—when Microsoft’s Recall threatens to capture everything users do, Signal responds by blocking screenshots in sensitive contexts. It’s a defensive move that highlights how privacy tools must evolve beyond their original scope just to maintain basic user agency in hostile platform environments.

This connects beautifully to Boyd Kane’s maze metaphor and Sean Tilley’s Fediverse vision. Kane shows how experts navigate familiar mazes whilst novices struggle with incomplete maps — exactly what’s happening with digital literacy right now. Tilley’s “Postmodern” platform offers a systemic solution: composable interfaces and user-controlled data architecture that could provide structural agency rather than forcing users to cobble together defensive measures. Where Signal fights against platform overreach, Postmodern would be designed to prevent such conflicts entirely.

Anil Dash’s framing of MCP as “Web 2.0 2.0” captures why this matters. The Model Context Protocol succeeds because it embraces interoperability over control—lightweight specifications that enable rather than constrain. This aligns perfectly with Adam Greenfield’s thermodynamic analysis: sustainable systems work with natural energy flows rather than against them. Platforms extract value by creating artificial scarcity; protocols create value by reducing friction. The RSA’s new badging framework sits somewhere between these approaches—institutional but potentially liberating if it genuinely recognises capabilities that traditional exams miss.

The systemic risks become clear when you look at John Loeber’s AI insurance analysis alongside IEEE’s microwave aviation piece. Both reveal how individual innovations can obscure massive infrastructure requirements. The aviation proposal needs 170-metre transmitters every 100 kilometres; AI insurance faces market concentration and information asymmetries. The LLM selection guide makes the same mistake — framing technical optimisation as the main challenge whilst ignoring questions about who controls access and how these choices affect digital equity.

What emerges is a picture of infrastructure in transition, where the most promising developments share a common characteristic: they’re designed to reduce rather than increase the expert-novice gap that Kane describes. Whether it’s MCP’s interoperability, Postmodern’s composable interfaces, or even Signal’s defensive privacy measures, the best approaches provide what I’d call capability infrastructure — systems that make it easier for people to develop digital agency rather than requiring them to become experts in underlying technologies. We’re all navigating mazes built by others, but we have a choice: build new mazes or create tools that help everyone find their way through.

Image: Wonderlane

The International Criminal Court ’s chief prosecutor has lost access to his email

In order to become individually or corporately wealthy you have to profit from someone else’s labour. If you push this to the limit, then you are likely to fall foul of the law, which is why rich individuals and Big Tech organisations have become increasingly close to governments.

This is particularly true in the increasingly-authoritarian USA, where non-compliance with the whims of the proto-dictator can have serious financial repercussions. So we find rich individuals and Big Tech companies being compliant in advance, in the former case winding down reputation washing philanthropic activities which might be seen as problematic, and in the latter, refusing or limiting access to technologies to those with different political or ideological views.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is “an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal… with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for the international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression.” It has issued an arrest warrant for Russian leader Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. So you can see why the ICC might be in the crosshairs of the Trump administration.

The International Criminal Court ’s chief prosecutor has lost access to his email, and his bank accounts have been frozen.

The Hague-based court’s American staffers have been told that if they travel to the U.S. they risk arrest.

Some nongovernmental organizations have stopped working with the ICC and the leaders of one won’t even reply to emails from court officials.

It’s the emails I want to focus on. Although we have to acknowledge and accept the fact that sometimes we have to use tools built by awful people to create beautiful things there are some organisations, like Microsoft, who continually been so problematic I try and have as little to do with them as possible.

One reason the the court has been hamstrung is that it relies heavily on contractors and non-governmental organizations. Those businesses and groups have curtailed work on behalf of the court because they were concerned about being targeted by U.S. authorities, according to current and former ICC staffers.

Microsoft, for example, cancelled Khan’s email address, forcing the prosecutor to move to Proton Mail, a Swiss email provider, ICC staffers said. His bank accounts in his home country of the U.K. have been blocked.

Microsoft did not respond to a request for comment.

Source: The Associated Press

Image: Le Vu

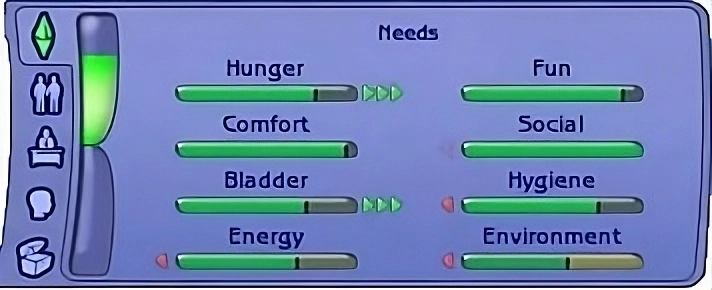

This is a major upgrade to how we think about personality.

I think it’s worth spending the time reading this article by Adam Mastroianni. The ‘SMTM’ acronym he mentions is ‘Slime Mold Time Mold’ the name of the group of his “mad scientist friends… who have just published a book that lays out a new foundation for the science of the mind” called The Mind in the Wheel. Mastroianni calls it “the most provocative thing I’ve read about psychology since I became a psychologist myself.”

Essentially, this is a cybernetic view of the mind. The easiest way to think of this is that the brain has a lot of control systems that work a bit like thermostats. For some systems, like breathing, people have largely the same tolerances and feedback loops. But for other (inferred) areas, such as sociability, things can be wildly different. This is why we talk about ‘introverts’ and ‘extraverts’.

If the mind is made out of control systems, and those control systems have different set points (that is, their target level) and sensitivities (that is, how hard they fight to maintain that target level), then “personality” is just how those set points and sensitivities differ from person to person. Someone who is more “extraverted”, for example, has a higher set point and/or greater sensitivity on their Sociality Control System (if such a thing exists). As in, they get an error if they don’t maintain a higher level of social interaction, or they respond to that error faster than other people do.

This is a major upgrade to how we think about personality. Right now, what is personality? If you corner a personality psychologist, they’ll tell you something like “traits and characteristics that are stable across time and situations”. Okay, but what’s a trait? What’s a characteristic? Push harder, and you’ll eventually discover that what we call “personality” is really “how you bubble things in on a personality test”. There are no units here, no rules, no theory about the underlying system and how it works. That’s why our best theory of personality performs about as well as the Enneagram, a theory that somebody just made up.

Not only do I think it is an interesting theory (psychology discovers systems thinking!) but Mastroianni also does a great job in distinguishing between science, and other things that are included in the field of psychology:

- Naive research (e.g. “Are people less likely to steal from the communal milk if you print out a picture of human eyes and hang it up in the break room?")

- Impressionistic research (e.g. “whether ‘mindfulness’ causes ‘resilience’ by increasing ‘zest for life’")

- Actual science (i.e. “making and testing conjectures about units and rules”)

This is why I’ve been drawn to systems thinking. It feels somewhat foundational in understanding how things work when you abstract away from immediate, everyday experience.

Like any good scientist, Mastroianni recognises that theories should not only be “falsifiable” in a Popperian sense, but “overturnable.” It may not be that everything runs on control systems, but wouldn’t it be interesting (as he points out, for everything from learning to animal welfare) if we found out that some of it did?

So, look. I do suspect that key pieces of the mind run on control systems. I also suspect that much of the mind has nothing to do with control systems at all. Language, memory, sensation—these processes might interface with control systems, but they themselves may not be cybernetic. In fact, cybernetic and non-cybernetic may turn out to be an important distinction in psychology. It would certainly make a lot more sense than dividing things into cognitive, social, developmental, clinical, etc., the way we do right now. Those divisions are given by the dean, not by nature.

Source & image: Experimental History

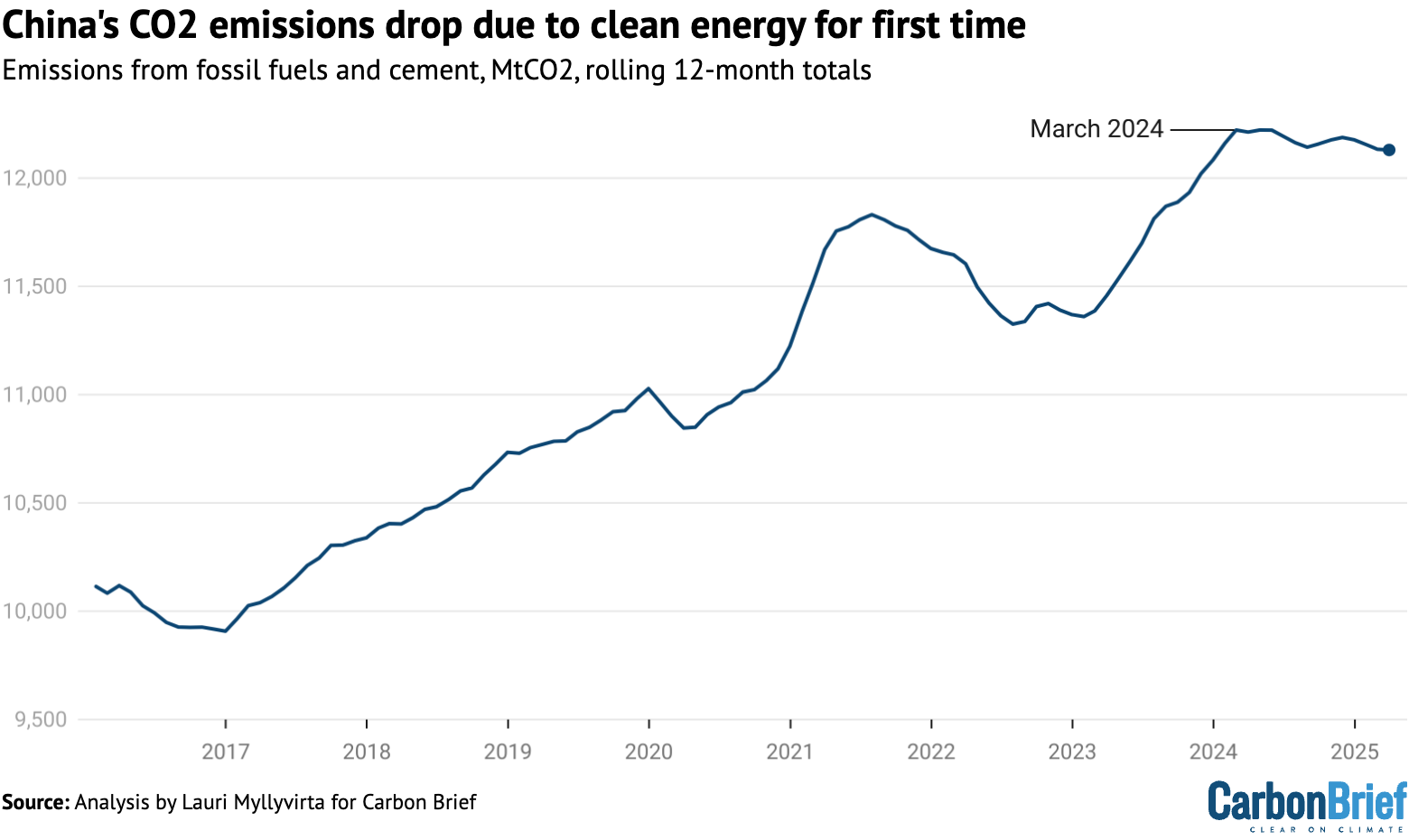

China starts to reduce CO2 emissions from energy generation

It’s nice to be able to share some good news about the state of the world, amidst the political doom and gloom. China has rapidly (and I mean rapidly) been building out renewable energy infrastructure, which is starting to pay dividends.

Meanwhile, in the UK we have opposition to Net Zero from reactionary politicians using massive solar panel installations as grist for their culture war mill. There are too many NIMBYs who object to things that can really make a different with regards to a green energy transition. The irony is, the way things are going, due to the climate emergency, they won’t even have a ‘backyard’ worth spending time in…

The reduction in China’s first-quarter CO2 emissions in 2025 was due to a 5.8% drop in the power sector. While power demand grew by 2.5% overall, there was a 4.7% drop in thermal power generation – mainly coal and gas.

Increases in solar, wind and nuclear power generation, driven by investments in new generating capacity, more than covered the growth in demand. The increase in hydropower, which is more related to seasonal variation, helped push down fossil power generation.

[…]

However, it’s not all good news:

Outside of the power sector, emissions increased 3.5%, with the largest rises in the use of coal in the metals and chemicals industries.

[…]

After exceptionally slow progress in 2020-23, China is significantly off track for its 2030 commitment to reduce carbon intensity – the emissions per unit of economic output. It is almost certain to miss its 2025 target. Carbon intensity fell by 3.4% in 2024, falling short of the rate of improvement needed to meet the 2025 and 2030 targets.

[…]

Even if emissions fell this year, improvements to carbon intensity would need to accelerate sharply in the next five years to meet China’s 2030 Paris commitment.

Source & image: Carbon Brief

The web is not merely an implementation of a particular legal privacy regime

This W3C Privacy Principles statement is really interesting. I don’t know of its origins, but it can’t be coincidental that it’s published a few months after a second Trump administration. It’s only since the rise of the GDPR and similar legislation, that anything other than Silicon Valley norms have been applied to the web.

Yesterday, at the Thinking Digital conference someone introduced a service that uses AI in the tools an organisation is already using to help them attain ISO 9001 compliance. It made me realise that principles such as the ones included in this statement, can be used to help provide guidelines and guardrails for LLMs as they increasingly shape our software — and our world.

As an example, I asked Perplexity to redesign Mastodon based on these principles. Here’s the result. While I’m not saying that an LLM is ‘correct’, product managers, developers, and designers having access to something that can quickly give feedback based on a document like this is, I think, incredibly useful.

Privacy on the web is primarily regulated by two forces: the architectural capabilities that the web platform exposes (or does not expose), and laws in the various jurisdictions where the web is used… These regulatory mechanisms are separate; a law in one country does not (and should not) change the architecture of the whole web, and likewise web specifications cannot override any given law (although they can affect how easy it is to create and enforce law). The web is not merely an implementation of a particular legal privacy regime; it has distinct features and guarantees driven by shared values that often exceed legal requirements for privacy.

However, the overall goal of privacy on the web is served best when technology and law complement each other. This document seeks to establish shared concepts as an aid to technical efforts to regulate privacy on the web. It may also be useful in pursuing alignment with and between legal regulatory regimes.

Our goal for this document is not to cover all possible privacy issues, but rather to provide enough background to support the web community in making informed decisions about privacy and in weaving privacy into the architecture of the web.

Few architectural principles are absolute, and privacy is no exception: privacy can come into tension with other desirable properties of an ethical architecture, including accessibility or internationalization, and when that happens the web community will have to work together to strike the right balance.

Source: W3C

Image: Kaspars Eglitis

The new tool should not replace or disrupt anything good that already exists

I think it’s hard to argue with Wendell Berry’s 1987 list of “standards for technological innovation” written to justify a refusal to replace his typewriter with a computer. It’s worth having a look at the original article as it includes responses from readers, as well as Berry’s rebuttals.

- The new tool should be cheaper than the one it replaces.

- It should be at least as small in scale as the one it replaces.

- It should do work that is clearly and demonstrably better than the one it replaces.

- It should use less energy than the one it replaces.

- If possible, it should use some form of solar energy, such as that of the body.

- It should be repairable by a person of ordinary intelligence, provided that he or she has the necessary tools.

- It should be purchasable and repairable as near to home as possible.

- It should come from a small, privately owned shop or store that will take it back for maintenance and repair.

- It should not replace or disrupt anything good that already exists, and this includes family and community relationships.

Source: The Honest Broker

Image: John Cameron

Unless there are many layers of contortions, most people love what loves them back.

Shani Zhang paints people at weddings. This post is her reflections on observing what she calls people’s “internal architecture.” Perhaps this is front-of-mind for me because we’re heading to another family wedding in a couple of weeks' time. But I think, in general, it’s good to think about the way you present yourself. Just not (as I have done for most of my life) _over_think it…

By internal architecture, what I mean is, when someone talks to me, what I notice first are the supporting beams propping up their words: the cadence and tone and desire behind them. I hear if they are bored, fascinated, wanting validation or connection. I often feel like I can hear how much they like themselves.

As Zhang sees people move between groups multiple times, on repeat, she has so many insights, especially around body language. For example:

I can see how much someone accepts themselves by looking for intense distortions in the way they are interacting with the world. Find the range in how they treat people; if there is a split difference in their stance towards people they admire, and people they look down on. I never met a person who looked down on others and unconditionally accepted themselves. For people who are self-accepting, it is usually less the case that some people are treated like they are golden and others like they are cursed. They may still have preferences to engage with some people over others, but their baseline patience and goodwill does not fall and rise intensely.

[…]

Some people don’t like themselves. They hide this from themselves by thinking they don’t like other people. They often bristle like a porcupine any time someone gets too close. That, or the opposite: they need to be insulated by other people’s skin at all times. These are contrasting expressions of the same fundamental fracture. A person cannot stand themselves, and as a result, they either can only stand being unperceived, or they need other people to constantly perceive them to feel okay.

Through the post, Zhang talks about different ways of being: open or closed, supportive or jealous. Ultimately, though, she settles on her favourite type of person:

My favorite kind of person has an elasticity in their movements. There is an openness that does not need to be announced, a curiosity that looks like turning towards all experience. They are not the loudest, but because they exhibit an unconditional acceptance of everyone, they are usually well loved. It makes sense, doesn’t it? Unless there are many layers of contortions, most people love what loves them back. Not desire, not need, love — to see them wholly, with gentleness and acceptance. If you are able to do that, most people will sense it. And they will try to love you back.

Source: skin contact

Image: Omar Lopez

Striving to build a “personal brand” may actually hinder your ability to make genuine connections and maintain a strong reputation

I really enjoyed this episode of the podcast WorkLife with Adam Grant. It’s ostensibly on ‘personal branding’ but the thing I want to share is the idea of a ‘failure résumé’. This is, as it sounds, a catalogue of things you’ve failed to achieve, both professionally and personally. I might create one.

The idea is that it helps with authenticity — as does, unsurprisingly, talking about how others have helped you get to where you are in life. It’s definitely worth a listen.

In the age of social media and influencers, we’re constantly pushed to think of ourselves as brands—shiny packages containing all of our best traits to market to employers and followers. But striving to build a “personal brand” may actually hinder your ability to make genuine connections and maintain a strong reputation. In this episode, Adam explores the science on alternatives to personal branding and explains why contribution, collaboration, and humility are better self-promotional tools than a carefully crafted image.

Source: WorkLife with Adam Grant (transcript)

Image: Franck

The Classroom AI Doom Loop

Recently, I convened a few people who I thought might be interested in writing something in response to a call from UNESCO for ‘think pieces’ around the subject of AI and the Future of Education: Disruptions, Dilemmas and Directions. You can read mine here and — whether or not the six of us have ours published — we’re planning to host a roundtable in early June to discuss our work.

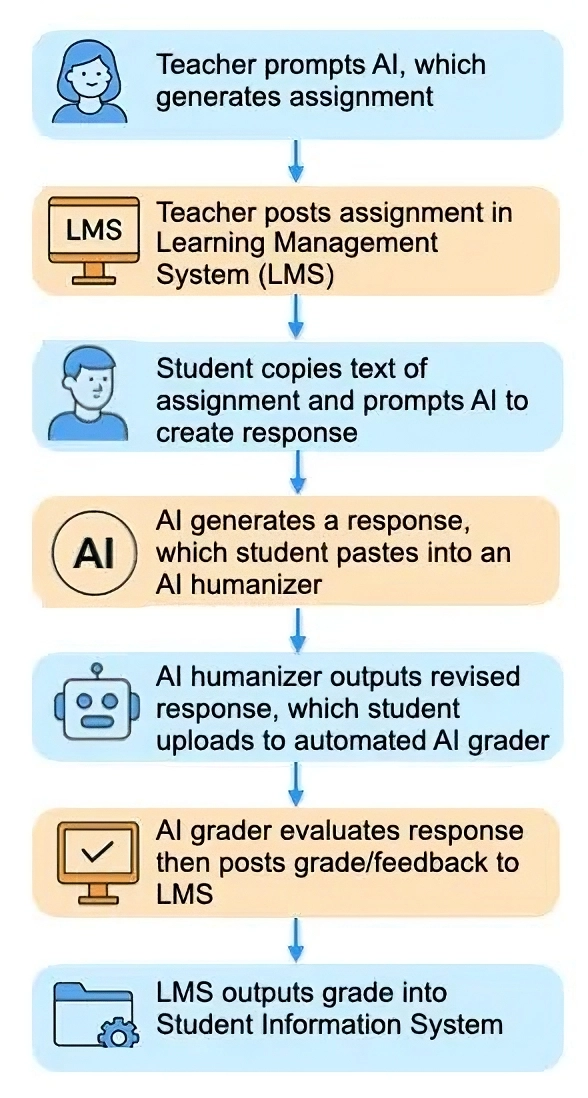

I had a look around the UNESCO Ideas LAB site, which is where the think pieces would be published, and came across this excellent article by David Ross. He coins the phrase “the classroom AI doom loop” which he illustrates with the diagram I’ve included above.

It’s this that concerns me about AI. Not the individual use, but its unthinking systemic embedding in an outdated system of assessment. You can blame the students. You can blame the teachers. But really, we need to step back and ask “what are we doing here?” and “what should we be doing here?” You can’t uninvent technologies, and banning the use of generative AI just feels like a game of whack-a-mole on steroids.

No humans were harmed in this process because humans were only ancillaries to the process. And this is today’s technology. By the beginning of the next school year, agentic AIs such as Manus, Convergence or Responses API will be able to eliminate humans from any involvement in the knowledge transmission cycle. If the last 100 years of technological innovation have taught us anything, it’s that if something can be automated, it will be automated.

Is this scenario really that far-fetched? Students and parents are busy and stressed. They hate homework because they have to give up their evenings and weekends to do it or monitor it. Teachers are busy and stressed. They hate homework because they have to give up their evenings and weekends creating it and then grading it. There is no conspiracy here, but humans will all choose to use AI for similar reasons.

Wouldn’t it be ironic if the solution to the industrial model of knowledge transmission is in fact automation?

[…]

We have come to the inflection point where we can automate most elements of knowledge transmission. I’m not sure if that is a good idea. But before we take up residence in the Classroom AI Doom Loop, we should have a serious policy discussion about the purpose of education. If a major function of education can be automated, it’s probably not human enough.

Source: UNESCO Ideas LAB

Image: original post (enhanced using upscale.media)

Chance favours the prepared mind

This is another one of those ‘collected wisdom’ lists which are like catnip for me. Mitch Horowitz the usual fare included, such as remembering to apologise, be curious, and show respect. But it was the following ten that jumped out at me. I’d also note that #95 is a different way of slicing-and-dicing my notion of increasing your serendipity surface.

#10 Judge quality not category.

#14 The loftier the language, the lower the behavior.

#18 Argue with a fool, make a fool your colleague.

#25 People see only those traits they possess.

#32 Brilliant people are wrong all the time.

#52 Unflinching perseverance is your single best chance of deliverance. Consider this lawful.

#59 There is no such thing as common sense.

#60 Emotions are far stronger than intellect.

#94 Accept paradox.

#95 “Chance favors the prepared mind.” (Pasteur)

Source: Mystery Achievement

Image: Kevin Luke

I think AI is a normal technology

This is a great post by Mike Caulfield, on many levels. Using the example of a tattoo containing a somewhat-obscure joke, which he asks various generative AI models to explain, he shows how much better ‘frontier’ LLMs are than last year’s offerings. Comparing the two shows how often criticisms about the abilities of generative AI are sometimes painfully out of date.

I’d agree with his last full paragraph, especially having lived through a fair few technology hype cycle. I’m sitting in a coffee shop drinking an Earl Grey tea that I paid for on my smartwatch. Unthinkable 20 years ago. Exciting 10 years ago. Boringly normal these days.

I’m not an AI utopian or dystopian. I think AI is a normal technology which will have a lot of impact but also take years to integrate before we start to reap substantial benefits, and that it’s incumbent on us to fight to make sure that the technology serves the public interest. But as the “normal technology” model acknowledges, the capabilities of AI are (still) advancing rapidly, even if the power of AI is going to develop slowly because the many issues which make it not suitable for full integration into processes that produce social/market value.

Source: The End(s) of Argument

Image: Elise Racine

It is perhaps likely then that at a time of crisis, these armed drones could be deployed operationally over the UK

A couple of days ago, one of our neighbour mentioned seeing a large, triangular drone-style object flying silently in the sky. Having seen someone else mentioned test flights of RAF drones recently, I did a bit of research.

The BBC reported back in February that “new RAF surveillance drones are being tested” being “controlled remotely” as part of “16 new surveillance drones… capable of operating in both UK and European airspace.” These ‘Protector’ drones will be tasked with “tracking threats, counter-terrorism and supporting the coastguard on search and rescue missions.”

Great, but let’s dig a bit deeper. How high do these things fly? What are they for? The RAF’s own information states that:

Capable of operating across the world with a minimal deployed footprint and remotely piloted from RAF Waddington, it can operate at heights up to 40,000 feet with an endurance of over 30 hours.

[…]

Equipped with a suite of surveillance equipment, the Protector aircraft will bring a critical global surveillance capability for the UK, all while being remotely piloted from RAF Waddington.

Surveillance? With a 30 hour flight time, I suppose that could be of other countries, but this feels something about which we should be having a national conversation. If they’re flying over UK skies, do they carry weapons? Drone Wars UK, a site which “investigates and challenges the development and use of armed drones and other new lethal military technology” suggests that do:

Protector differs from its predecessor in that it can carry more weapons and fly further and for longer. However the UK argues that the main advantage of the new drone is that it was built to standards that allowed it to be flown in civil airspace alongside other aircraft.

Rather than be based overseas as the UK’s current fleet of armed drones are, the new drone will be based at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire and deploy directly for overseas operations from there.

[…]

Significantly, the new drone has been brought in with the understanding that it can also be used at times of crisis for operations within the UK under Military Aid to Civil Authorities (MACA) rules. It is perhaps likely then that at a time of crisis, the UK’s armed drone could be deployed operationally over the UK.

On the one hand, yes I want the UK to have the ability to intercept threats from foreign actors and terrorists. But I also don’t want the government and military to have the kind of surveillance and weaponry that can be turned against our own population. Just to be clear, these are the very military drones we used in Afghanistan against the Taliban 🤔

Sources: Royal Air Force News / Drone Wars

Image: POA(Phot) Tam McDonald/MOD (Wikimedia Commons)

You can now use Bluesky without using Bluesky infrastructure

One of the criticisms of Twitter-replacement ‘decentralised’ social network Bluesky has been that… it’s not decentralised. Laurens Hof, author of The Fediverse Report shares a couple of updates explaining how that has changed.

There’s quite a lot going on technically here, so by way of preparation, understand that ‘ATProto’ is short for ‘Authenticated Transfer Protocol’ and is an open standard for distributed social networking services. You may have heard of ActivityPub, which underpins a lot of Fediverse services, including Mastodon.

Bluesky is a bit different in that it has more essential services to make the whole thing work. As Laurens explains:

One of the things that makes ATProto interesting… is that it takes the software that runs a social networking app, and splits that up into separate components. These infrastructure components (relays and AppViews, in technical terms) can be independently run, and be reused by other parties.

Up until recently, there have been a few low-key experiments with running independent infrastructure for Bluesky, but that has mostly been contained to people experimenting for themselves, and not making the results accessible to the public. These projects also needed other infrastructure projects in order to be valuable.

What changed in the last week or so is that there are now multiple pieces of independent infrastructure that connects these separate pieces. Apps like Deer are useful in their own right, but in order to add some new features to the app they needed another open backend application (the AppView). It also was the first time when it actually was possible to select another AppView. At this point it actually became feasible to run independent relays and AppViews to get to a point where you can use Bluesky without using Bluesky infrastructure.

As he goes on to explain in a separate update, this means:

There are now multiple relays that are publicly accessible. Other people also have made alternate AppViews that are Bluesky-compatible. Combined, this makes it now possible to fully use Bluesky without using any infrastructure owned by Bluesky PBC, and the first people have done so. To do so means using a separate PDS, relay, AppView and client.

The way ATProto works, is that it takes the software that runs a social network and splits it up into separate components, with each of those components being able to be run independently. This has made self-hosting any component possible since the beginning of the network opening up. But to tak advantage of this, and get to a state of full independence, it means running multiple pieces of software. This has created a bit of a catch-22 in the ecosystem: you could run your own relay, but without another independent AppView to take advantage of this, it is not super useful. You could run your own (focused on the Bluesky lexicon) AppView, but without a client that allows you to set your own AppView it is not particularly useful either. What happened now in the last weeks is that all these individual pieces are starting to come together. With Deer allowing you to set your own custom AppView, there is now a use to actually run your own AppView. Which in turn also gives more purpose to running your own relay.

I get that this is pretty technical, but it means that those with the skills can build independent platforms (e.g. Blacksky) which are based on the same protocol. Posts, notes, and other data can be shared among ATProto-compatible systems.

This is great news, and makes me more inclined to go back to posting more than just updates from my blog. Feel free to follow me @dougbelshaw.com.

Sources: Fediverse Report – #115 / Bluesky Report– #115

Image: Yohan Marion

You stop performing. You stop pretending. And that’s freedom.

Once a week, I get into my gym stuff, and head down to a couple of coffee shops. In the first one, which opens earlier than the other, I have a pot of Earl Grey tea. In the other, I have a Flat White with coconut milk and two slices of brown toast with butter and marmalade. In the first, which is locally-owned, they’ve started preparing my drink as I walk in. In the latter, a Costa Coffee, I often have to repeat my order and ask for an extra patty of butter each time.

Which is to say that I am a man of routine. I think routines are absolutely fundamental to living a creative and/or productive life. They lower the number of individual decisions you have to make, and therefore stave off ‘decision fatigue’ — something I’ve written about recently on Thought Shrapnel as well as a few times over the years:

- Decision fatigue and parenting (2018)

- The impact of decision fatigue (2021)

- Taking breaks to be more human (2021)

The problem with routines, though is that they can become ossified. And I think it’s that which makes us “old”. People who know me well are know how fond I am of Clay Shirky’s observation that “current optimization is long-term anachronism.”

All of which is by way of introduction to a post by Katy Cowan about “getting old” not being what you think. She’s a few years older than me, it would appear, as she says that she turns 50 soon. We do, however, share membership of the Xennial micro-generation — again, something I’ve discussed recently and previously.

For me, having unexpectedly developed a heart condition at the start of my 45th year on this earth, this “getting old” thing has felt like much more of a sudden process than what Katy discusses in this post. However, what it contains is not only a nostalgia trip, but solid advice for anyone approaching, or in, the middle years of life.

We’re a small generation, often overlooked, but we’ve lived through more change than most—from mixtapes to Spotify, from faxes to WhatsApp, from digital revolution to AI. And because we existed in that liminal space, we carry a weird dual wisdom: we know how to live offline, but we can thrive online, too.

We understand the value of privacy and impermanence because we remember a time before everything was public and permanent. And maybe that’s why so many of us are quietly deleting our social media accounts and leaning into real life again — books, dinners, walks, actual phone calls. Imagine!

[…]

These days, I sometimes catch myself muttering at the telly, shaking my head at a clueless reality show contestant, thinking: You just wait, sunshine. You’ll get old, too. And yes, I do roll my eyes at some of the newer buzzwords. But I try to check myself. Because if ageing has taught me anything, it’s that the biggest danger is certainty.

That’s the tension, isn’t it? The constant tug-of-war between feeling grumpy and still clinging to some version of youth. I never thought I’d be that person. But here I am.

[…]

So here’s what I try to remember, at any age: stay curious. Never assume you’re right. Read the newspapers you’d generally avoid. Challenge even your most cherished opinions. Try to see more than one side. You won’t always succeed, but it’s worth the effort.

Because if growing older has taught me anything, it’s this: certainty is overrated, and listening is wildly underrated. Cosy nights in don’t mean you’ve given up. They just mean you know what you like — and that maybe, just maybe, you never truly loved going to gigs as much as you pretended to. You stop performing. You stop pretending. And that’s freedom.

Source: Katy Cowan

Image: Hasse Lossius

Authoritarian versions of AI used to consolidate power

One of the main problems of generative AI being deployed via a chatbot user interface is that it feels private. It feels like a direct message conversation. Of course, on the other side of the conversation is a black box controlled by Big Tech. You have to use these things carefully. As Mike Caulfield points out AI is not your friend.

This week, the day after OpenAI announced that it was backtracking on becoming a fully for-profit organisation, they announced ‘OpenAI for Countries’. This intitiative, it seems, is an attempt to still build the ‘moat’ required for economic dominance and control of the ecosystem — but using the backing of state infrastructure rather than venture capital funding.

Colour me sceptical, but the press release suggests that the Trump administration hasn’t happened and that the US is still some kind of force for democratic development. Instead, I’d argue, the “authoritarian versions of AI” used “to consolidate power” are exactly what is represented by a level of AI colonialism that only something like a collaboration between OpenAI and the US government could achieve.

Our Stargate project, an unprecedented investment in America’s AI infrastructure announced in January with President Trump and our partners Oracle and SoftBank, is now underway with our first supercomputing campus in Abilene, Texas, and more sites to come.

We’ve heard from many countries asking for help in building out similar AI infrastructure—that they want their own Stargates and similar projects. It’s clear to everyone now that this kind of infrastructure is going to be the backbone of future economic growth and national development. Technological innovation has always driven growth by helping people do more than they otherwise could—AI will scale human ingenuity itself and drive more prosperity by scaling our freedoms to learn, think, create and produce all at once.

We want to help these countries, and in the process, spread democratic AI, which means the development, use and deployment of AI that protects and incorporates long-standing democratic principles. Examples of this include the freedom for people to choose how they work with and direct AI, the prevention of government use of AI to amass control, and a free market that ensures free competition. All these things contribute to broad distribution of the benefits of AI, discourage the concentration of power, and help advance our mission. Likewise, we believe that partnering closely with the US government is the best way to advance democratic AI.

Today, we’re introducing OpenAI for Countries, a new initiative within the Stargate project. This is a moment when we need to act to support countries around the world that would prefer to build on democratic AI rails, and provide a clear alternative to authoritarian versions of AI that would deploy it to consolidate power.

Source: OpenAI

If you think that humans are somehow inherently more trustworthy than AI, then you haven't been paying attention

I came across this via a recent post on OLDaily by Stephen Downes, who mentioned it while critiquing what I would call an information literacy approach to AI literacy.

The book How to Read Donald Duck is “a 1971 book-length essay by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart that critiques Disney comics from a Marxist point of view as capitalist propaganda for American corporate and cultural imperialism.” I haven’t read it, and so I’m not in a position to comment. However, I would point out that it’s possible to spread an ideology (or a perceived one) without being aware that you are an adherent of it.

I thought Downes' post was interesting, and worth publicly bookmarking, not only for mentioning this book but also for putting into words something that I’ve felt: “if you think that humans are somehow inherently more trustworthy than AI, then you haven’t been paying attention.”

The book’s thesis is that Disney comics are not only a reflection of the prevailing ideology at the time (capitalism), but that the comics' authors are also aware of this, and are active agents in spreading the ideology.

[…]

[Any] closeness to everyday life is so only in appearance, because the world shown in the comics, according to the thesis, is based on ideological concepts, resulting in a set of natural rules that lead to the acceptance of particular ideas about capital, the developed countries' relationship with the Third World, gender roles, etc.

As an example, the book considers the lack of descendants of the characters. Everybody has an uncle or nephew, everybody is a cousin of someone, but nobody has fathers or sons. This non-parental reality creates horizontal levels in society, where there is no hierarchic order, except the one given by the amount of money and wealth possessed by each, and where there is almost no solidarity among those of the same level, creating a situation where the only thing left is crude competition. Another issue analyzed is the absolute necessity to have a stroke of luck for social mobility (regardless of the effort or intelligence involved), the lack of ability of the native tribes to manage their wealth, and others.

Source: Wikipedia

Image: Taha

An effective way to implement GenAI into assessment

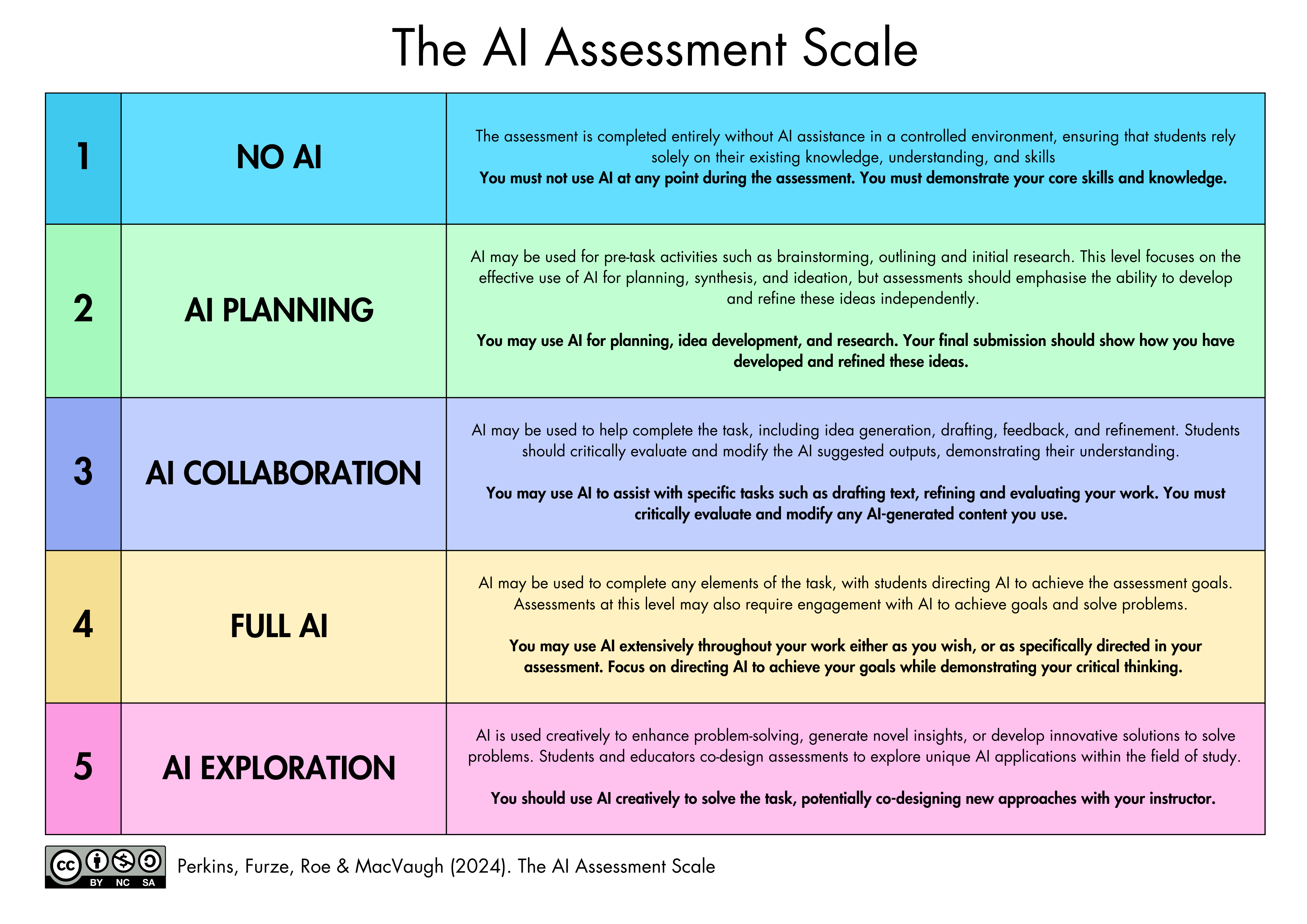

As part of the project I’m working on at the moment, I had a chat with Leon Furze earlier this week. Leon has co-authored something called the AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) which I think is pretty useful.

Like my ‘Essential Elements of Digital Literacies’ from my thesis which seeks to provide building blocks for building definitions and frameworks, the aim of the AIAS is “to guide the appropriate and ethical use of generative AI in assessment design.”

The AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) was developed by Mike Perkins, Leon Furze, Jasper Roe, and Jason MacVaugh. First introduced in 2023 and updated in Version 2 (2024), the Scale provides a nuanced framework for integrating AI into educational assessments.

The AIAS has been adopted by hundreds of schools and universities worldwide, translated into 29 languages, and is recognised by organisations such as the Australian Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) as an effective way to implement GenAI into assessment.

To my mind, this should be used as a heuristic, much as I used to use the SAMR model (discussed here) to help educators think about the appropriate use of different technologies. At the end of the day, educators need to think about assessment design in tandem with the technologies being used — officially or unofficially — to complete it.

Source: AI Assessment Scale