The internet may function not so much as a brainwashing engine but as a justification machine

“Do your own research” is the mantra of the conspiracy theorist. It turns out that if you search for evidence of something on the internet, you’ll find it. Want proof that the earth is flat? There’s plenty of nutjob articles, videos, and podcasts for that. As there is for almost anything you can possibly imagine.

This post by Charlie Warzel and Mike Caulfield focuses on the attack on the US Capitol four years ago for The Atlantic is based on this larger observation about the internet as a ‘justification machine’. As an historian, it makes me sad that when people refer to the “wider context” of a present-day event, they rarely go back more than a few months — or, at the most, a few years.

For example, I read a fantastic book on the history of Russia over the holiday period which really helped me understand the current invasion of Ukraine. I haven’t seen that mentioned once as part of the news cycle. It’s always on to the next thing, almost always presented through the partisan lens of some flavour of capitalism.

Lately, our independent work has coalesced around a particular shared idea: that misinformation is powerful, not because it changes minds, but because it allows people to maintain their beliefs in light of growing evidence to the contrary. The internet may function not so much as a brainwashing engine but as a justification machine. A rationale is always just a scroll or a click away, and the incentives of the modern attention economy—people are rewarded with engagement and greater influence the more their audience responds to what they’re saying—means that there will always be a rush to provide one. This dynamic plays into a natural tendency that humans have to be evidence foragers, to seek information that supports one’s beliefs or undermines the arguments against them. Finding such information (or large groups of people who eagerly propagate it) has not always been so easy. Evidence foraging might historically have meant digging into a subject, testing arguments, or relying on genuine expertise. That was the foundation on which most of our politics, culture, and arguing was built.

The current internet—a mature ecosystem with widespread access and ease of self-publishing—undoes that.

[…]

Conspiracy theorizing is a deeply ingrained human phenomenon, and January 6 is just one of many crucial moments in American history to get swept up in the paranoid style. But there is a marked difference between this insurrection (where people were presented with mountains of evidence about an event that played out on social media in real time) and, say, the assassination of John F. Kennedy (where the internet did not yet exist and people speculated about the event with relatively little information to go on). Or consider the 9/11 attacks: Some did embrace conspiracy theories similar to those that animated false-flag narratives of January 6. But the adoption of these conspiracy theories was aided not by the hyperspeed of social media but by the slower distribution of early online streaming sites, message boards, email, and torrenting; there were no centralized feeds for people to create and pull narratives from.

The justification machine, in other words, didn’t create this instinct, but it has made the process of erasing cognitive dissonance far more efficient. Our current, fractured media ecosystem works far faster and with less friction than past iterations, providing on-demand evidence for consumers that is more tailored than even the most frenzied cable news broadcasts can offer.

[…]

The justification machine thrives on the breakneck pace of our information environment; the machine is powered by the constant arrival of more news, more evidence. There’s no need to reorganize, reassess. The result is a stuckness, a feeling of being trapped in an eternal present tense.

Source: The Atlantic

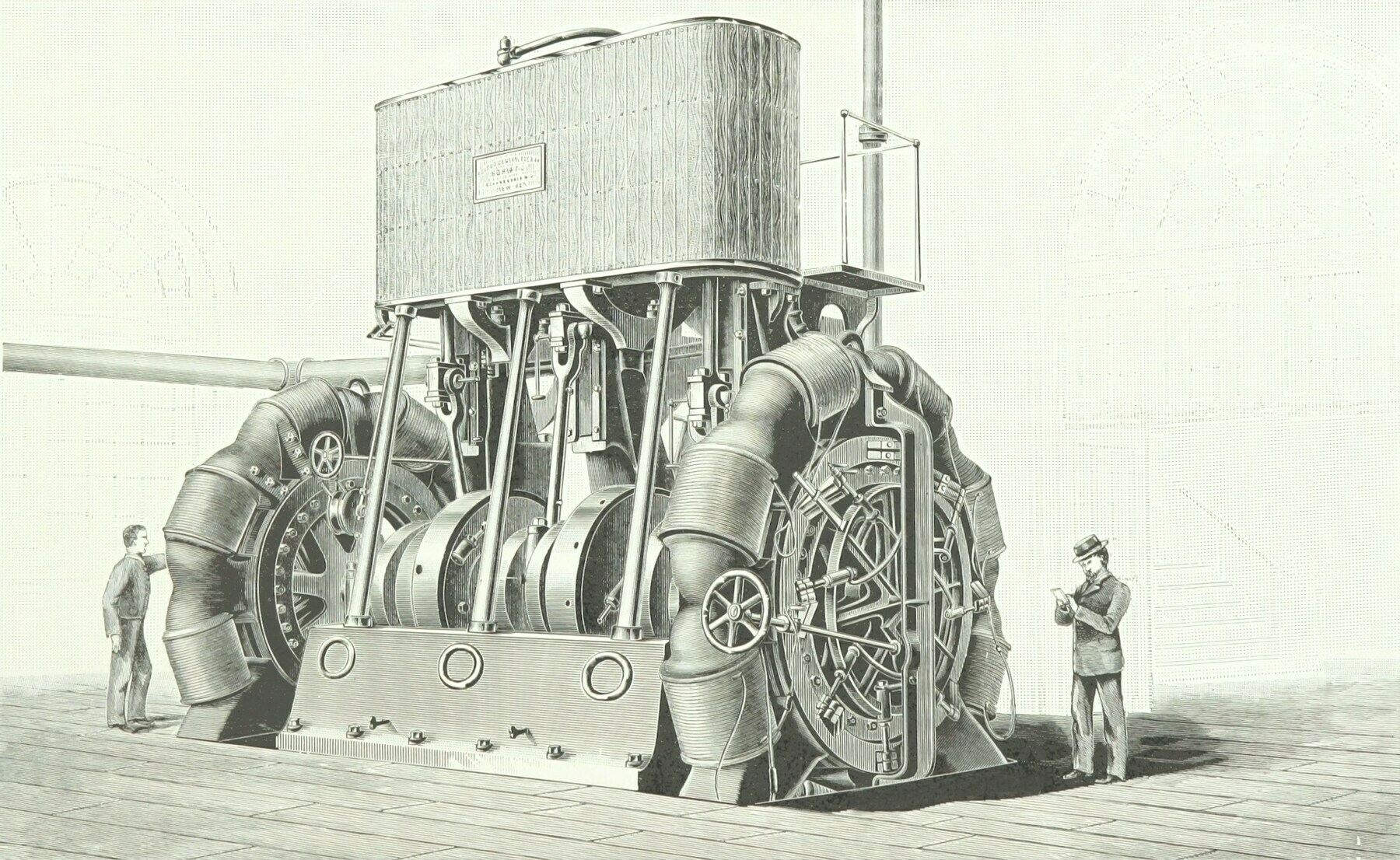

Image: British Library