A philosophical approach to performative language

I don’t know anything about Ariel Pontes, the author of this article, other than seeing that they’re a member of the Effective Altruism community. (Which is a small red flag in and of itself, as it tends to be full of hyper-rationalist solutionist dudes.)

However, what I appreciate about this loooooong article is that Pontes applies philosophical concepts I’ve come across before to talk about the different roles language can play across the political divide.

People are not just tricked into believing falsities anymore, they no longer care about what’s true or false as long as it supports their narratives and hashtags. But can we draw a sharp boundary between smart, rational, objective people, and crazy, fact-denying post-truthers? Or do we all use non-factual language to some extent? What are we really doing when we say things like “meat is murder” or “all lives matter”?Source: Performative language. How philosophy of language can help us… | Ariel Pontes[…]

Most people would probably agree, if asked, that humans are prone to black-and-white thinking, and that this is bad. But few of us actually make as constant conscious effort to avoid this tendency of ours in our daily lives. Our tribal brains are quick to label people as belonging either to our team of that of the enemy, for example, and it’s hard to accept that there are many possibilities in between.

[...]

Once we start seeing language as a tool used to play different games, it becomes natural to ask: what types of games are people playing out there? In his lecture series posthumously published as How To Do Things With Words, J. L. Austin introduces the concept of a “performative utterance” or “speech act”, a sentence that does not describe or “constate” any fact, but performs an action.

[...]

In his lectures about performative utterances, Austin introduces what he calls the descriptive fallacy. This fallacy is committed when somebody interprets a performative utterance as merely descriptive, subsequently dismissing it as false or nonsense when in fact it has a very important role, it’s just that this role is not simply stating facts. If somebody goes on vacation after a stressful period at work and, as they finally lie on their beach chair in their favorite resort with their favorite cocktail in their hands, they say “life is good”, it would be absurd to say “this statement is meaningless because it cannot be empirically verified”. Clearly it is an expression of a state of mind that doesn’t really have a factual dimension at all.

What’s important to emphasize here, however, is that those who attack speech acts as false or meaningless are as guilty as the descriptive fallacy as those who defend their performative utterances on factual grounds, which is regrettably common. People are not usually aware that, besides labelling a statement as “true” or “false”, they can also label it as “purely performative, lacking factual content”. The performative nature of language is not something people are explicitly aware of in general. As a consequence, when a statement is phrased as factual but is confusing and hard to grasp as factually true, our intuitive reaction is to label it as false. On the other hand, if a statement becomes part of our identity as consequence of being used as the slogan of a movement we strongly support, we feel tempted to defend it as factually true even though it might be quite plainly false or factually meaningless.

[...]

Language is complex. A statement can always be interpreted in many ways. In the age of social media, where a tweet can be read by millions of people, it is always possible that somebody will read a malicious insinuation into an genuinely well intended comment. Because of this, it is often helpful to say what you don’t mean. Of course, no matter how much effort we make, somebody might always attack us. This is a reality we have to simply come to terms with. But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

A philosophical approach to performative language

I don’t know anything about Ariel Pontes, the author of this article, other than seeing that they’re a member of the Effective Altruism community. (Which is a small red flag in and of itself, as it tends to be full of hyper-rationalist solutionist dudes.)

However, what I appreciate about this loooooong article is that Pontes applies philosophical concepts I’ve come across before to talk about the different roles language can play across the political divide.

People are not just tricked into believing falsities anymore, they no longer care about what’s true or false as long as it supports their narratives and hashtags. But can we draw a sharp boundary between smart, rational, objective people, and crazy, fact-denying post-truthers? Or do we all use non-factual language to some extent? What are we really doing when we say things like “meat is murder” or “all lives matter”?Source: Performative language. How philosophy of language can help us… | Ariel Pontes[…]

Most people would probably agree, if asked, that humans are prone to black-and-white thinking, and that this is bad. But few of us actually make as constant conscious effort to avoid this tendency of ours in our daily lives. Our tribal brains are quick to label people as belonging either to our team of that of the enemy, for example, and it’s hard to accept that there are many possibilities in between.

[...]

Once we start seeing language as a tool used to play different games, it becomes natural to ask: what types of games are people playing out there? In his lecture series posthumously published as How To Do Things With Words, J. L. Austin introduces the concept of a “performative utterance” or “speech act”, a sentence that does not describe or “constate” any fact, but performs an action.

[...]

In his lectures about performative utterances, Austin introduces what he calls the descriptive fallacy. This fallacy is committed when somebody interprets a performative utterance as merely descriptive, subsequently dismissing it as false or nonsense when in fact it has a very important role, it’s just that this role is not simply stating facts. If somebody goes on vacation after a stressful period at work and, as they finally lie on their beach chair in their favorite resort with their favorite cocktail in their hands, they say “life is good”, it would be absurd to say “this statement is meaningless because it cannot be empirically verified”. Clearly it is an expression of a state of mind that doesn’t really have a factual dimension at all.

What’s important to emphasize here, however, is that those who attack speech acts as false or meaningless are as guilty as the descriptive fallacy as those who defend their performative utterances on factual grounds, which is regrettably common. People are not usually aware that, besides labelling a statement as “true” or “false”, they can also label it as “purely performative, lacking factual content”. The performative nature of language is not something people are explicitly aware of in general. As a consequence, when a statement is phrased as factual but is confusing and hard to grasp as factually true, our intuitive reaction is to label it as false. On the other hand, if a statement becomes part of our identity as consequence of being used as the slogan of a movement we strongly support, we feel tempted to defend it as factually true even though it might be quite plainly false or factually meaningless.

[...]

Language is complex. A statement can always be interpreted in many ways. In the age of social media, where a tweet can be read by millions of people, it is always possible that somebody will read a malicious insinuation into an genuinely well intended comment. Because of this, it is often helpful to say what you don’t mean. Of course, no matter how much effort we make, somebody might always attack us. This is a reality we have to simply come to terms with. But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

Technological Liturgies

A typically thoughtful article from L. M. Sacasas in which they “explore a somewhat eccentric frame by which to consider how we relate to our technologies, particularly those we hold close to our bodies.” It’s worth reading the whole thing, especially if you grew up in a church environment as it will have particular resonance.

I would propose that we take a liturgical perspective on our use of technology. (You can imagine the word “liturgical” in quotation marks, if you like.) The point of taking such a perspective is to perceive the formative power of the practices, habits, and rhythms that emerge from our use of certain technologies, hour by hour, day by day, month after month, year in and year out. The underlying idea here is relatively simple but perhaps for that reason easy to forget. We all have certain aspirations about the kind of person we want to be, the kind of relationships we want to enjoy, how we would like our days to be ordered, the sort of society we want to inhabit. These aspirations can be thwarted in any number of ways, of course, and often by forces outside of our control. But I suspect that on occasion our aspirations might also be thwarted by the unnoticed patterns of thought, perception, and action that arise from our technologically mediated liturgies. I don’t call them liturgies as a gimmick, but rather to cast a different, hopefully revealing light on the mundane and commonplace. The image to bear in mind is that of the person who finds themselves handling their smartphone as others might their rosary beads.Source: Taking Stock of Our Technological Liturgies | The Convivial Society[…]

Say, for example, that I desire to be a more patient person. This is a fine and noble desire. I suspect some of you have desired the same for yourselves at various points. But patience is hard to come by. I find myself lacking patience in the crucial moments regardless of how ardently I have desired it. Why might this be the case? I’m sure there’s more than one answer to this question, but we should at least consider the possibility that my failure to cultivate patience stems from the nature of the technological liturgies that structure my experience. Because speed and efficiency are so often the very reason why I turn to technologies of various sorts, I have been conditioning myself to expect something approaching instantaneity in the way the world responds to my demands. If at every possible point I have adopted tools and devices which promise to make things faster and more efficient, I should not be surprised that I have come to be the sort of person who cannot abide delay and frustration.

[…]

The point of the exercise is not to divest ourselves of such liturgies altogether. Like certain low church congregations that claim they have no liturgies, we would only deepen the power of the unnoticed patterns shaping our thought and actions. And, more to the point, we would be ceding this power not to the liturgies themselves, but to the interests served by those who have crafted and designed those liturgies. My loneliness is not assuaged by my habitual use of social media. My anxiety is not meaningfully relieved by the habit of consumption engendered by the liturgies crafted for me by Amazon. My health is not necessarily improved by compulsive use of health tracking apps. Indeed, in the latter case, the relevant liturgies will tempt me to reduce health and flourishing to what the apps can measure and quantify.

Technological Liturgies

A typically thoughtful article from L. M. Sacasas in which they “explore a somewhat eccentric frame by which to consider how we relate to our technologies, particularly those we hold close to our bodies.” It’s worth reading the whole thing, especially if you grew up in a church environment as it will have particular resonance.

I would propose that we take a liturgical perspective on our use of technology. (You can imagine the word “liturgical” in quotation marks, if you like.) The point of taking such a perspective is to perceive the formative power of the practices, habits, and rhythms that emerge from our use of certain technologies, hour by hour, day by day, month after month, year in and year out. The underlying idea here is relatively simple but perhaps for that reason easy to forget. We all have certain aspirations about the kind of person we want to be, the kind of relationships we want to enjoy, how we would like our days to be ordered, the sort of society we want to inhabit. These aspirations can be thwarted in any number of ways, of course, and often by forces outside of our control. But I suspect that on occasion our aspirations might also be thwarted by the unnoticed patterns of thought, perception, and action that arise from our technologically mediated liturgies. I don’t call them liturgies as a gimmick, but rather to cast a different, hopefully revealing light on the mundane and commonplace. The image to bear in mind is that of the person who finds themselves handling their smartphone as others might their rosary beads.Source: Taking Stock of Our Technological Liturgies | The Convivial Society[…]

Say, for example, that I desire to be a more patient person. This is a fine and noble desire. I suspect some of you have desired the same for yourselves at various points. But patience is hard to come by. I find myself lacking patience in the crucial moments regardless of how ardently I have desired it. Why might this be the case? I’m sure there’s more than one answer to this question, but we should at least consider the possibility that my failure to cultivate patience stems from the nature of the technological liturgies that structure my experience. Because speed and efficiency are so often the very reason why I turn to technologies of various sorts, I have been conditioning myself to expect something approaching instantaneity in the way the world responds to my demands. If at every possible point I have adopted tools and devices which promise to make things faster and more efficient, I should not be surprised that I have come to be the sort of person who cannot abide delay and frustration.

[…]

The point of the exercise is not to divest ourselves of such liturgies altogether. Like certain low church congregations that claim they have no liturgies, we would only deepen the power of the unnoticed patterns shaping our thought and actions. And, more to the point, we would be ceding this power not to the liturgies themselves, but to the interests served by those who have crafted and designed those liturgies. My loneliness is not assuaged by my habitual use of social media. My anxiety is not meaningfully relieved by the habit of consumption engendered by the liturgies crafted for me by Amazon. My health is not necessarily improved by compulsive use of health tracking apps. Indeed, in the latter case, the relevant liturgies will tempt me to reduce health and flourishing to what the apps can measure and quantify.

Three components of the public sphere

My views on monarchy are, well, that there shouldn’t be one in my country, nor should there be any in the world. This post by Ethan Zuckerman goes into three levels of reaction around the death of Elizabeth II, but more interestingly explains his thinking behind a new experimental course he’s running this semester.

As I thought through the hundreds of ideas I wanted to share over the course of twenty-something lectures, I’ve centered on three core concepts I want to try and get across. The first is simple: democracy requires a robust and healthy public sphere, and American democracy was designed with that public sphere as a core component.Source: The Monarchy, the Subaltern and the Public Sphere | Ethan ZuckermanSecond – and this one has taken me more time to understand – the public sphere includes at least three components: a way of knowing what’s going on in the world (news), a space for discussing public life, and whatever precursors allow individuals to participate in these discussions. For Habermas’s public sphere, those precursors included being male, wealthy, white, urban and literate… hence the need for Nancy Fraser’s recognition of subaltern counterpublics. Public schooling and libraries are anchored in the idea of enabling people to participate in the public sphere.

The third idea is that as technology and economic models change, all three of these components – the nature of news, discourse, and access – change as well. The obvious change we’re focused on is the displacement of a broadcast public sphere by a highly participatory digital public sphere, but we can see previous moments of upheaval: the rise of mass media with the penny press, the rise of propaganda as broadcast media puts increased control of the public sphere in the hands of corporations and governments.

Three components of the public sphere

My views on monarchy are, well, that there shouldn’t be one in my country, nor should there be any in the world. This post by Ethan Zuckerman goes into three levels of reaction around the death of Elizabeth II, but more interestingly explains his thinking behind a new experimental course he’s running this semester.

As I thought through the hundreds of ideas I wanted to share over the course of twenty-something lectures, I’ve centered on three core concepts I want to try and get across. The first is simple: democracy requires a robust and healthy public sphere, and American democracy was designed with that public sphere as a core component.Source: The Monarchy, the Subaltern and the Public Sphere | Ethan ZuckermanSecond – and this one has taken me more time to understand – the public sphere includes at least three components: a way of knowing what’s going on in the world (news), a space for discussing public life, and whatever precursors allow individuals to participate in these discussions. For Habermas’s public sphere, those precursors included being male, wealthy, white, urban and literate… hence the need for Nancy Fraser’s recognition of subaltern counterpublics. Public schooling and libraries are anchored in the idea of enabling people to participate in the public sphere.

The third idea is that as technology and economic models change, all three of these components – the nature of news, discourse, and access – change as well. The obvious change we’re focused on is the displacement of a broadcast public sphere by a highly participatory digital public sphere, but we can see previous moments of upheaval: the rise of mass media with the penny press, the rise of propaganda as broadcast media puts increased control of the public sphere in the hands of corporations and governments.

Ad-free urban spaces

I've never understood why we allow so much advertising in our lives. Thankfully, I live in a small town without that much of it, but it's always a massive culture shock when I go to a city. So I very much support this campaign led by Charlotte Gage of Adfree Cities.

Related: over the last few years, I've got my kids into the habit of pressing the mute button during advert breaks on TV. This makes the adverts seem even more ridiculous, allows for conversation, and still allows you to see when the programme you're watching comes back on!

"These ads are in the public space without any consultation about what is shown on them," she says. "Plus they cause light pollution, and the ads are for things people can't afford, or don't need."

Ms Gage is the network director of UK pressure group Adfree Cities, which wants a complete ban on all outdoor corporate advertising. This would also apply to the sides of buses, and on the London Underground and other rail and metro systems.

[...]

Ms Gage says that while there are "ethical issues with junk food ads, pay day loans and high-carbon products [in particular], people would rather see community ads and art rather than have multi-billion dollar companies putting logos and images everywhere".

Ad-free urban spaces

I've never understood why we allow so much advertising in our lives. Thankfully, I live in a small town without that much of it, but it's always a massive culture shock when I go to a city. So I very much support this campaign led by Charlotte Gage of Adfree Cities.

Related: over the last few years, I've got my kids into the habit of pressing the mute button during advert breaks on TV. This makes the adverts seem even more ridiculous, allows for conversation, and still allows you to see when the programme you're watching comes back on!

"These ads are in the public space without any consultation about what is shown on them," she says. "Plus they cause light pollution, and the ads are for things people can't afford, or don't need."

Ms Gage is the network director of UK pressure group Adfree Cities, which wants a complete ban on all outdoor corporate advertising. This would also apply to the sides of buses, and on the London Underground and other rail and metro systems.

[...]

Ms Gage says that while there are "ethical issues with junk food ads, pay day loans and high-carbon products [in particular], people would rather see community ads and art rather than have multi-billion dollar companies putting logos and images everywhere".

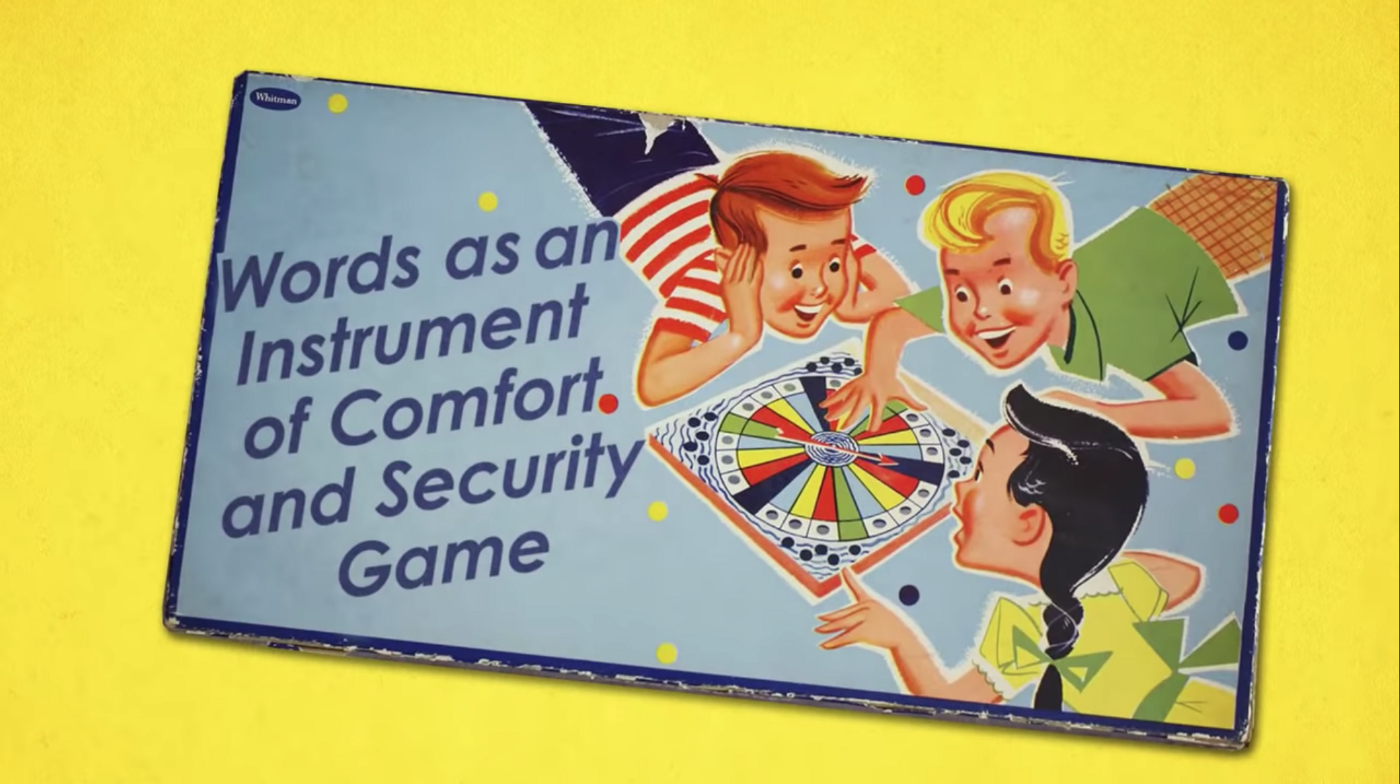

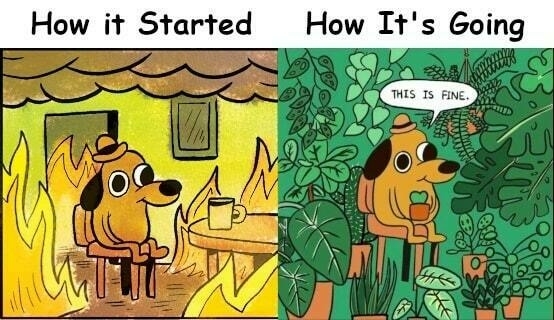

Life product tiers

A bit of fun from xkcd, but with some underlying truth in terms of how people experience life almost as if it were different product tiers.

Source: xkcd: Universe Price Tiers

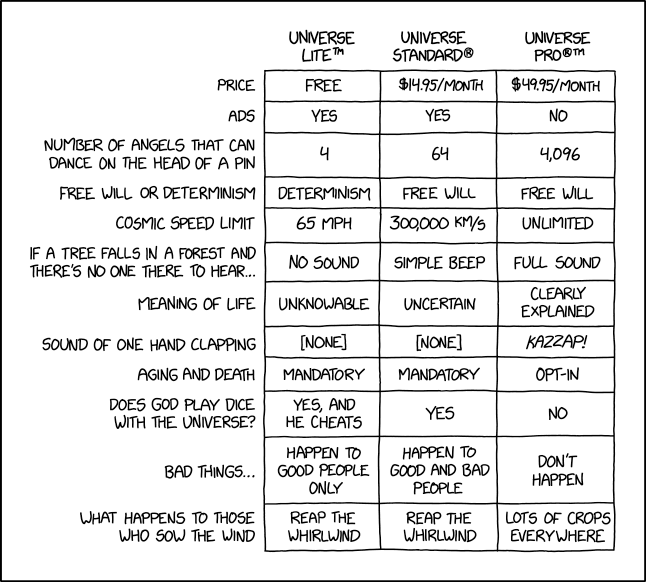

Population ethics

Will MacAskill is an Oxford philosopher. He’s an influential member of the Effective Altruism movement and has a view of the world he calls ‘longtermism’. I don’t know him, and I haven’t read his book, but I have done some ethics as part of my Philosophy degree.

As a parent, I find this review of his most recent book pretty shocking. I’m willing to consider most ideas but utilitarianism is the kind of thing which is super-attractive as a first-year Philosophy student but which… you grow out of?

The review goes more into depth than I can here, but human beings are not cold, calculating machines. We’re emotional people. We’re parents. And all I can say is that, well, my worldview changed a lot after I became a father.

Oxford philosophers William MacAskill and Toby Ord, both affiliated with the university’s Future of Humanity Institute, coined the word “longtermism” five years ago. Their outlook draws on utilitarian thinking about morality. According to utilitarianism—a moral theory developed by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill in the nineteenth century—we are morally required to maximize expected aggregate well-being, adding points for every moment of happiness, subtracting points for suffering, and discounting for probability. When you do this, you find that tiny chances of extinction swamp the moral mathematics. If you could save a million lives today or shave 0.0001 percent off the probability of premature human extinction—a one in a million chance of saving at least 8 trillion lives—you should do the latter, allowing a million people to die.Source: The New Moral Mathematics | Boston ReviewNow, as many have noted since its origin, utilitarianism is a radically counterintuitive moral view. It tells us that we cannot give more weight to our own interests or the interests of those we love than the interests of perfect strangers. We must sacrifice everything for the greater good. Worse, it tells us that we should do so by any effective means: if we can shave 0.0001 percent off the probability of human extinction by killing a million people, we should—so long as there are no other adverse effects.

[…]

MacAskill spends a lot of time and effort asking how to benefit future people. What I’ll come back to is the moral question whether they matter in the way he thinks they do, and why. As it turns out, MacAskill’s moral revolution rests on contentious, counterintuitive claims in “population ethics.”

[…]

[W]hat is most alarming in his approach is how little he is alarmed. As of 2022, the ‘Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ set the Doomsday Clock, which measures our proximity to doom, at 100 seconds to midnight, the closest it’s ever been. According to a study commissioned by MacAskill, however, even in the worst-case scenario—a nuclear war that kills 99 percent of us—society would likely survive. The future trillions would be safe. The same goes for climate change. MacAskill is upbeat about our chances of surviving seven degrees of warming or worse: “even with fifteen degrees of warming,” he contends, “the heat would not pass lethal limits for crops in most regions.”

This is shocking in two ways. First, because it conflicts with credible claims one reads elsewhere. The last time the temperature was six degree higher than preindustrial levels was 251 million years ago, in the Permian-Triassic Extinction, the most devastating of the five great extinctions. Deserts reached almost to the Arctic and more than 90 percent of species were wiped out. According to environmental journalist Mark Lynas, who synthesized current research in ‘Our Final Warning: Six Degrees of Climate Emergency’ (2020), at six degrees of warming the oceans will become anoxic, killing most marine life, and they’ll begin to release methane hydrate, which is flammable at concentrations of five percent, creating a risk of roving firestorms. It’s not clear how we could survive this hell, let alone fifteen degrees.

Conversational affordances

I’m one of those people who has to try hard not to over-analyse everything. Therapy has helped a bit, but I still can’t help reflecting on conversations I’ve had with people outside my family.

Why did that conversation go so well? Why was another one boring? Did I talk too much?

That sort of thing.

Which is why I found this article about ‘conversational doorknobs’ and improvisational comedy fascinating.

For me, learning take-and-take suggested a solution not just to songs about Spiderman, but to a scientific mystery. I was in graduate school at the time, running studies aimed at answering the question, “Do conversations end when people want them to?” I watched a stupefying number of conversations unfold, some of them blooming into beautiful repartee (one pair of participants exchanged numbers afterward), others collapsing into awkward silences. Why did some conversations unfurl and others wilt? One answer, I realized, may be the clash of take-and-take vs. give-and-take.There’s people I interact with on a semi-regular basis for which I, like other people, am just a convenient person to talk at. It can be entertaining for a while, but can get a bit too much. Likewise, there are others where I feel like I have to do most of the talking, and that’s just tiring.Givers think that conversations unfold as a series of invitations; takers think conversations unfold as a series of declarations. When giver meets giver or taker meets taker, all is well. When giver meets taker, however, giver gives, taker takes, and giver gets resentful (“Why won’t he ask me a single question?”) while taker has a lovely time (“She must really think I’m interesting!”) or gets annoyed (“My job is so boring, why does she keep asking me about it?”).

It’s easy to assume that givers are virtuous and takers are villainous, but that’s giver propaganda. Conversations, like improv scenes, start to sink if they sit still. Takers can paddle for both sides, relieving their partners of the duty to generate the next thing. It’s easy to remember how lonely it feels when a taker refuses to cede the spotlight to you, but easy to forget how lovely it feels when you don’t want the spotlight and a taker lets you recline on the mezzanine while they fill the stage. When you’re tired or shy or anxious or bored, there’s nothing better than hopping on the back of a conversational motorcycle, wrapping your arms around your partner’s waist, and holding on for dear life while they rocket you to somewhere new.

The best thing is when the two of your have a shared interest and you’re willing to take turns in asking questions and opening doorways. I’m not saying that I’m a particularly skilled conversationalist, but having attended a lot of events during my career, I’m better at it now than I used to be.

When done well, both giving and taking create what psychologists call affordances: features of the environment that allow you to do something. Physical affordances are things like stairs and handles and benches. Conversational affordances are things like digressions and confessions and bold claims that beg for a rejoinder. Talking to another person is like rock climbing, except you are my rock wall and I am yours. If you reach up, I can grab onto your hand, and we can both hoist ourselves skyward. Maybe that’s why a really good conversation feels a little bit like floating.Source: Good conversations have lots of doorknobs | Experimental HistoryWhat matters most, then, is not how much we give or take, but whether we offer and accept affordances. Takers can present big, graspable doorknobs (“I get kinda creeped out when couples treat their dogs like babies”) or not (“Let me tell you about the plot of the movie ‘Must Love Dogs’…”). Good taking makes the other side want to take too (“I know! My friends asked me to be the godparent to their Schnauzer, it’s so crazy” “What?? Was there a ceremony?”). Similarly, some questions have doorknobs (“Why do you think you and your brother turned out so different?”) and some don’t (“How many of your grandparents are still living?”). But even affordance-less giving can be met with affordance-ful taking (“I have one grandma still alive, and I think a lot about all this knowledge she has––how to raise a family, how to cope with tragedy, how to make chocolate zucchini bread––and how I feel anxious about learning from her while I still can”).

[…]

A few unfortunate psychological biases hold us back from creating these conversational doorknobs and from grabbing them when we see them. We think people want to hear about exciting stuff we did without them (“I went to Budapest!”) when they actually are happier talking about mundane stuff we did together (“Remember when we got stuck in traffic driving to DC?”). We overestimate the awkwardness of deep talk and so we stick to the boring, affordance-less shallows. Conversational affordances often require saying something at least a little bit intimate about yourself, so even the faintest fear of rejection on either side can prevent conversations from taking off. That’s why when psychologists want to jump-start friendship in the lab, they have participants answer a series of questions that require steadily escalating amounts of self-disclosure (you may have seen this as “The 36 Questions that Lead to Love”).

Doomed to live in a Sisyphean purgatory between insatiable desires and limited means

I’m reading The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow. It’s an eye-opening book in many ways, and upends notions of how we see the way that people used to live.

This article suggests that 15-hour working weeks are the norm in egalitarian cultures. While working hours are steadily declining, we’re still a long way off — primarily because our desires and means are out of kilter.

New genomic and archeological data now suggest that Homo sapiens first emerged in Africa about 300,000 years ago. But it is a challenge to infer how they lived from this data alone. To reanimate the fragmented bones and broken stones that are the only evidence of how our ancestors lived, beginning in the 1960s anthropologists began to work with remnant populations of ancient foraging peoples: the closest living analogues to how our ancestors lived during the first 290,000 years of Homo sapiens’ history.Source: The 300,000-year case for the 15-hour week | Financial TimesThe most famous of these studies dealt with the Ju/’hoansi, a society descended from a continuous line of hunter-gatherers who have been living largely isolated in southern Africa since the dawn of our species. And it turned established ideas of social evolution on their head by showing that our hunter-gatherer ancestors almost certainly did not endure “nasty, brutish and short” lives. The Ju/’hoansi were revealed to be well fed, content and longer-lived than people in many agricultural societies, and by rarely having to work more than 15 hours per week had plenty of time and energy to devote to leisure.

Subsequent research produced a picture of how differently Ju/’hoansi and other small-scale forager societies organised themselves economically. It revealed, for instance, the extent to which their economy sustained societies that were at once highly individualistic and fiercely egalitarian and in which the principal redistributive mechanism was “demand sharing” — a system that gave everyone the absolute right to effectively tax anyone else of any surpluses they had. It also showed how in these societies individual attempts to either accumulate or monopolise resources or power were met with derision and ridicule.

Most importantly, though, it raised startling questions about how we organise our own economies, not least because it showed that, contrary to the assumptions about human nature that underwrite our economic institutions, foragers were neither perennially preoccupied with scarcity nor engaged in a perpetual competition for resources.

For while the problem of scarcity assumes that we are doomed to live in a Sisyphean purgatory, always working to bridge the gap between our insatiable desires and our limited means, foragers worked so little because they had few wants, which they could almost always easily satisfy. Rather than being preoccupied with scarcity, they had faith in the providence of their desert environment and in their ability to exploit this.

Teaching about dead white guys in an age of social media

I’m pleased that I completed my formal education and moved out of teaching before social media transformed the world. In this article, Marie Snyder talks about teaching an introductory Philosophy course (the subject of my first degree) and the pushback she’s had from students.

There’s a lot I could write about this which would be uninteresting, so just go and read her article. All I’ll say is that, personally, I still listen to musicians (like Morrissey) whose political views I find abhorrent. Part of diversity is diversifying your own thinking.

It’s important that we scrutinize behaviours. It’s useful to clarify that discrimination or harm of any kind — from former cultural appropriation to sexual crimes — is not to be tolerated. We should definitely overtly chastise damaging behaviours of people as a means to shift society to evolve down the best timeline. But we are all greater than our worst actions; for instance, Heidegger’s overt anti-semitism doesn’t obliterate his theories of being. His student and lover, Hannah Arendt, is another name potentially requested stricken from syllabi for a collection of racist comments despite her quarrel with her mentor about his bigoted position.Source: On Tossing the Canon in a Cannon | 3 Quarks DailyWe have to look at ideas, not people, when sifting the wheat from the chaff. Some ideas stand the test of time even if their author is found otherwise wanting. It doesn’t suggest that they’re an honourable person when we find a piece of work worthy of our attention, and it’s not like we’re contributing to their wealth if they’re long dead. We need to bring back a nuanced approach to these works instead of the current dichotomous path of slotting people in a good or bad box.

Steaming open the institutional creases

This is a heart-rending article by Maria Farrell, who suffers from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. She details her experiences for Long Covid suffers, and it’s not easy reading.

I’m including this quotation mainly because she talks about the impact of the Tory government in the UK over the last decade or so. It’s easy to forget that things didn’t use to be like this

I hid for two years in graduate school, the first year in a wonderful and academically undemanding programme with a tiny, lovely class. I wrote an essay about Walter Benjamin and interactive media that winter, and I remember pulling each sentence rather brutally from the morass of my former abilities and piling them on top of each other. Let’s just say the angel of history made sense to me in a way she had not, before. Minute on minute, I could barely make the letters settle into words, forget about forming sentences or ideas, but day on day it turned out I could do it. It just took a higher threshold of discomfort than I’d previously believed manageable, and about eight times longer. I’m so glad I learnt this. The knowledge that impossibly difficult intellectual tasks can be worked through piecemeal – not in darts and dashes of caffeinated brilliance – was not natural to my temperament, and it’s why I can still do things.Source: Settling in for the long haul | Crooked TimberIt’s a very bourgeois thing to be able to hide out in grad school. I’m always embarrassed when people remark on how many degrees I have. It put me into financial penury for quite a few years, but it felt worth it to still outwardly look like a person who was moving forward in life, not someone whose clock had stopped in August 1998 when I failed to heal from glandular fever. All that is harder now in Britain, as Tories systematically steam open the institutional creases people like me could fold ourselves into, and dismantle the social welfare that would have held many others as they waited to be well. I started off with moderate M.E. and now, much of the time, I would say it is mild.

Steaming open the institutional creases

This is a heart-rending article by Maria Farrell, who suffers from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. She details her experiences for Long Covid suffers, and it’s not easy reading.

I’m including this quotation mainly because she talks about the impact of the Tory government in the UK over the last decade or so. It’s easy to forget that things didn’t use to be like this

I hid for two years in graduate school, the first year in a wonderful and academically undemanding programme with a tiny, lovely class. I wrote an essay about Walter Benjamin and interactive media that winter, and I remember pulling each sentence rather brutally from the morass of my former abilities and piling them on top of each other. Let’s just say the angel of history made sense to me in a way she had not, before. Minute on minute, I could barely make the letters settle into words, forget about forming sentences or ideas, but day on day it turned out I could do it. It just took a higher threshold of discomfort than I’d previously believed manageable, and about eight times longer. I’m so glad I learnt this. The knowledge that impossibly difficult intellectual tasks can be worked through piecemeal – not in darts and dashes of caffeinated brilliance – was not natural to my temperament, and it’s why I can still do things.Source: Settling in for the long haul | Crooked TimberIt’s a very bourgeois thing to be able to hide out in grad school. I’m always embarrassed when people remark on how many degrees I have. It put me into financial penury for quite a few years, but it felt worth it to still outwardly look like a person who was moving forward in life, not someone whose clock had stopped in August 1998 when I failed to heal from glandular fever. All that is harder now in Britain, as Tories systematically steam open the institutional creases people like me could fold ourselves into, and dismantle the social welfare that would have held many others as they waited to be well. I started off with moderate M.E. and now, much of the time, I would say it is mild.

Is our society structured in a way which encourages people to make less than the greatest contribution they could?

Colin Percival is the founder of Tarsnap which is a somewhat-niche cryptographically-secure backup solution. In this post, he replies to a comment he saw that he’s potentially wasting his life on something less important than the world’s biggest problems.

His point, I think, is that starting your own business is the only way these days of being able to do the kind of deep work which people like him find fulfilling. So I guess the question is whether there’s an even better way of structuring society to enable even greater contribution?

First, to dispense with the philosophical argument: Yes, this is my life, and yes, I'm free to use — or waste — it however I please; but I don't think there's anything wrong with asking if this is how my time could be best spent. That applies doubly if the question is not merely about the choices I made but is rather a broader question: Is our society structured in a way which encourages people to make less than the greatest contribution they could?Source: On the use of a life | Daemonic Dispatches[…]

In many ways, starting my own company has given me the sort of freedom which academics aspire to. Sure, I have customers to assist, servers to manage (not that they need much management), and business accounting to do; but professors equally have classes to teach, students to supervise, and committees to attend. When it comes to research, I can follow my interests without regard to the whims of granting agencies and tenure and promotion committees: I can do work like scrypt, which is now widely known but languished in obscurity for several years after I published it; and equally I can do work like kivaloo, which has been essentially ignored for close to a decade, with no sign of that ever changing.

[…]

Is there a hypothetical world where I would be an academic working on the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture right now? Sure. It’s probably a world where high-flying students are given, upon graduation, some sort of “mini-Genius Grant”. If I had been awarded a five-year $62,500/year grant with the sole condition of “do research”, I would almost certainly have persevered in academia and — despite working on the more interesting but longer-term questions — have had enough publications after those five years to obtain a continuing academic position. But that’s not how granting agencies work; they give out one or two year awards, with the understanding that those who are successful will apply for more funding later.

Losing followers, making friends

There’s a lot going on in this article, which I’ve taken plenty of quotations from below. It’s worth taking some time over, especially if you haven’t read Thinking, Fast & Slow (or it’s been a while since you did!)

Social media inherited and weaponised the chronological weblog feed. Showing content based on user activity hooked us in for longer. When platforms discovered anger and anxiety boosts screen time, the battle for our minds was lost.Source: Escaping The Web’s Dark Forest | by Steve LordTill this point the fundamental purpose of software was to support the user’s objectives. Somewhere, someone decided the purpose of users is to support the firm’s objectives. This shift permeates through the Internet. It’s why basic software is subscription-led. It’s why there’s little functional difference between Windows’ telemetry and spyware. It’s why leaving social media is so hard.

Like chronological timelines, users grew to expect these patterns. Non-commercial platforms adopted them because users expect them. While not as optimized as their commercial counterparts, inherited anti-patterns can lead to inherited behaviours.

[…]

In his book Thinking Fast And Slow, Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman describes two systems of thought…

[…]

System 1 appears to prioritise speed over accuracy, which makes sense for Lion-scale problems. System 1 even cheats to avoid using System 2. When faced with a difficult question, System 1 can substitute it and answer a simpler one. When someone responds to a point that was never made that could be a System 1 substitution.

[…]

10 Years ago my life was extremely online. I’ve been the asshole so many times I can’t even count. Was I an asshole? Sure, but the exploitation of mental state in public spaces has a role to play. It’s a strange game. The only way to win is not to play.

Commercial platforms are filled with traps, some inherited, many homegrown. Wrapping it in Zuck’s latest bullshit won’t lead to change. Even without inherited dark patterns, behaviours become ingrained. Platforms designed to avoid these patterns need to consider this if exposed to the Dark Forest.

For everything else it’s becoming easier to just stay away. There are so many private and semi-private spaces far from the madding crowd. You just need to look. I did. I lost followers, but made friends.

Muting the American internet

This is a humorous article, but one with a point.

[W]e need a way to mute America. Why? Because America has no chill. America is exhausting. America is incapable of letting something be simply funny instead of a dread portent of their apocalyptic present. America is ruining the internet.Source: I Should Be Able to Mute America | Gawker[…]

The greatest trick America’s ever pulled on the subjects of its various vassal states is making us feel like a participant in its grand experiment. After all, our fate is bound to the American empire’s whale fall. My generation in particular is the first pure batch of Yankee-Yobbo mutoids: as much Hank Hill as we are Hills Hoist (look it up!), as familiar with the Supreme Court Justices as we are with the judges on Master Chef, as comfortable in Frasier’s Seattle or Seinfeld’s Upper West Side as we are in Ramsay Street or Summer Bay.

[…]

I should not know who Pete Buttigieg is. In a just world, the name Bari Weiss would mean as much to me as Nordic runes. This goes for people who actually might read Nordic runes too. No Swede deserves to be burdened with this knowledge. No Brazilian should have to regularly encounter the phrase “Dimes Square.” To the rest of the vast and varied world, My Pillow Guy and Papa John should be NPCs from a Nintendo DS Zelda title, not men of flesh and bone, pillow and pizza. Ted Cruz should be the name of an Italian pornstar in a Love Boat porn parody. Instead, I’m cursed to know that he is a senator from Texas who once stood next to a butter sculpture of a dairy cow and declared that his daughter’s first words were “I like butter.”

Muting the American internet

This is a humorous article, but one with a point.

[W]e need a way to mute America. Why? Because America has no chill. America is exhausting. America is incapable of letting something be simply funny instead of a dread portent of their apocalyptic present. America is ruining the internet.Source: I Should Be Able to Mute America | Gawker[…]

The greatest trick America’s ever pulled on the subjects of its various vassal states is making us feel like a participant in its grand experiment. After all, our fate is bound to the American empire’s whale fall. My generation in particular is the first pure batch of Yankee-Yobbo mutoids: as much Hank Hill as we are Hills Hoist (look it up!), as familiar with the Supreme Court Justices as we are with the judges on Master Chef, as comfortable in Frasier’s Seattle or Seinfeld’s Upper West Side as we are in Ramsay Street or Summer Bay.

[…]

I should not know who Pete Buttigieg is. In a just world, the name Bari Weiss would mean as much to me as Nordic runes. This goes for people who actually might read Nordic runes too. No Swede deserves to be burdened with this knowledge. No Brazilian should have to regularly encounter the phrase “Dimes Square.” To the rest of the vast and varied world, My Pillow Guy and Papa John should be NPCs from a Nintendo DS Zelda title, not men of flesh and bone, pillow and pizza. Ted Cruz should be the name of an Italian pornstar in a Love Boat porn parody. Instead, I’m cursed to know that he is a senator from Texas who once stood next to a butter sculpture of a dairy cow and declared that his daughter’s first words were “I like butter.”

Morality, responsibility, and (online) information

This is a useful article in terms of thinking about the problems we have around misinformation online. Yes, we have a responsibility to be informed citizens, but there are structural issues which are actively working against that.

How might we alleviate our society’s misinformation problem? One suggestion goes as follows: the problem is that people are so ignorant, poorly informed, gullible, irrational that they lack the ability to discern credible information and real expertise from incredible information and fake expertise.Source: On the moral responsibility to be an informed citizen | Psyche Ideas[…]

This view places the primary responsibility for our current informational predicament – and the responsibility to mend it – on individuals. It views them as somehow cognitively deficient. An attractive aspect of this view is that it suggests a solution (people need to become smarter) directly where the problem seems to lie (people are not smart). Simply, if we want to stop the spread of misinformation, people need to take responsibility to think better and learn how to stop spreading it. A closer philosophical and social scientific look at issues of responsibility with regard to information suggests that this view is mistaken on several accounts.

[…]

Even if there was a mass willingness to accept accountability, or if a responsibility could be articulated without blaming citizens, there is no guarantee that citizens would be successful in actually practising their responsibility to be informed. As I said, even the best intentions are often manipulated. Critical thinking, rationality and identifying the correct experts are extremely difficult things to practise effectively on their own, much less in warped information environments. This is not to say that people’s intentions are universally good, but that even sincere, well-meaning efforts do not necessarily have desirable outcomes. This speaks against proposing a greater individual responsibility for misinformation, because, if even the best intentions can be corrupted, then there isn’t a great chance of success.

[…]

Leaning away from individual responsibility means that the burden should be shifted to those who have structural control over our information environments. Solutions to our misinformation epidemic are effective when they are structural and address the problem at its roots. In the case of online misinformation, we should understand that technology giants aim at creating profit over creating public democratic goods. If disinformation can be made to be profitable, we should not expect those who profit to self-regulate and adopt a responsibility toward information by default. Placing accountability and responsibility on technology companies but also on government, regulatory bodies, traditional media and political parties by democratic means is a good first step to foster information environments that encourage good knowledge practices. This step provides a realistic distribution of both causal and effective remedial responsibility for our misinformation problem without nihilistically throwing out the entire concept of responsibility – which we should never do.