- Higher income & education demographics - Information-seeking traffic predominates, e.g., news, mail, search; Instagram, WhatsApp and Twitter are the dominant social media apps; games like Clash of Clans are the most widely used, …

- Lower income & education demographics - Entertainment traffic predominates, e.g., video-streaming, gaming, adult services; Facebook and Snapchat are the dominant social media apps; games like Candy Crush are the most widely used, …

The new digital divide

We’re already at the stage where most people in the developed world have a device that can access the internet in their pocket. Many families have multiple devices in their house that can access the internet. We’re getting to the stage where that’s starting to be the case in developing countries.

So the new digital divide? How we use the internet. I think there’s a lot to unpack here, especially as we live in unequal societies dominated by hyper-capitalism. It would be easy to victim blame, but I know from experience that when I’m burned out, all I want to do is stare and scroll at my phone…

In his seminar, Moro referred to the socio-economic divide based on how we use the internet as the second digital divide, in contrast to the original digital divide which was based on access to the internet.Source: The Digital Divide in How We Use the Internet | Irving Wladawsky-BergerGetting online in the 1990s required a personal computer and an account with a service provider, and e-commerce transactions required a credit card and bank account. As our economy was becoming increasingly digital, major new inequalities were now arising because so many around the world could neither afford a PC or an internet account and had no bank relationship or credit card. The reach and connectivity we were all so excited about in this initial phase of the internet era was in reality not so inclusive. While the internet was truly empowering for those with the means to use it, it led to a growing digital divide both within countries and across the world. The internet was ushering a global digital revolution, but it was disconcerting to have a global digital revolution that left out the majority of the world’s population.

This picture started to change in the 2000s. Continuing technology advances were now bringing the empowerment benefits of the digital revolution to a majority of the planet’s population. Mobile phones and wireless internet access went from a luxury to a necessity that most everyone could now afford, initially in advanced economies, and later in most of the rest of the world. We were transitioning from the connected economy of PCs, browsers and web servers to an increasingly hyperconnected digital economy of ubiquitous, powerful and inexpensive mobile devices, cloud-based apps, and broadband wireless networks.

While the original internet access gap is now minimal in developed economies, Moro and his collaborators found that a digital usage gap has now emerged, representing the distinct uses of the internet by different socio-economic groups based primarily on their income and educational status.

[…]

The study found quantitative evidence of a significant digital divide in internet usage between two socio-economic groups, each with different income and educational attainment. In principle, all individuals had access to the same internet. But, the study found that each group generally accessed its own distinct version of the internet, and their socio-economic behavior was thus influenced by the fairly different services and information that they were exposed to. By analyzing mobile traffic flows, the study identified the key services that each group accessed:

“The digital usage gap is so profound between low- and high-income or low- or high-education areas that it can be used to clearly distinguish between them or even identify the relative composition of these groups in a given area,” wrote the authors. “High-income areas or those with higher education attainability show a more pronounced utilization of mobile devices to consume news, exchange e-mails, search for information or listen to music. At the same time, they display a reduced use of some social media platforms or video-streaming services.

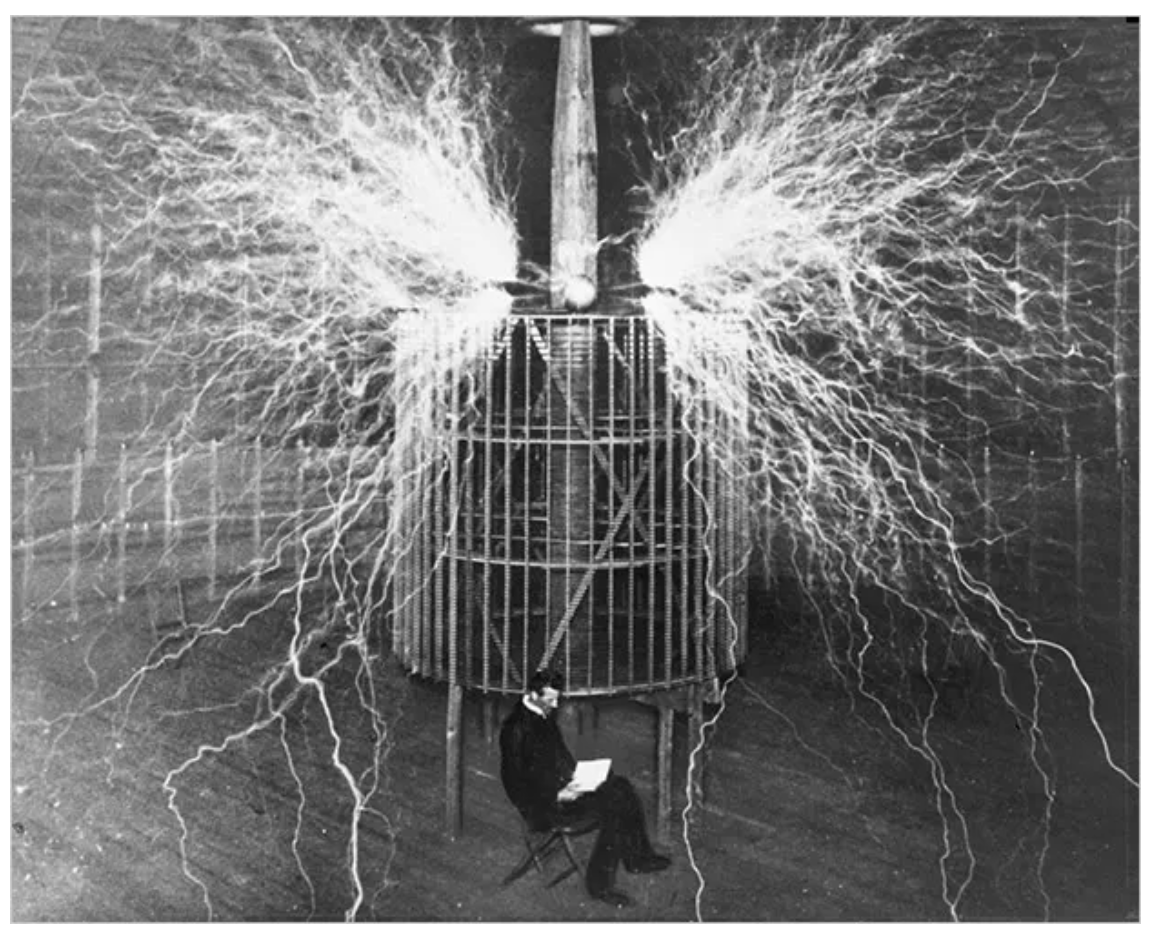

Image source: Robin Worrall

Signalling that you're AFK in a world where you can never really be AFK

I used AIM and MSN Messenger as a teenager, from around 1996 to about 2001. It was great, and I remember messaging with friends and the woman who is now my wife using it.

Part of the whole experience of it was that you were using the service on a shared device, a computer that the rest of the family would use. In that sense, it was more like a text-based landline phone. It wasn’t personal like the smart devices that live in our pockets these days.

There a lot of nostalgia about how things used to be, and we’re certainly not going back to shared devices as a primary means of getting online anytime soon. So that means that we need other ways of respecting one another’s boundaries. This is something we can actually reclaim ourselves by responding to messages on our own terms.

Sometimes you had to step away. So you threw up an Away Message: I’m not here. I’m in class/at the game/my dad needs to use the comp. I’ve left you with an emo quote that demonstrates how deep I am. Or, here’s a song lyric that signals I am so over you. Never mind that my Away Message is aimed at you.Source: It's Time to Bring Back the AIM Away Message | WIREDI miss Away Messages. This nostalgia is layered in abstraction; I probably miss the newness of the internet of the 1990s, and I also miss just being … away. But this is about Away Messages themselves—the bits of code that constructed Maginot Lines around our availability. An Away Message was a text box full of possibilities, a mini-MySpace profile or a Facebook status update years before either existed. It was also a boundary: An Away Message not only popped up as a response after someone IM’d you, it was wholly visible to that person b they IM’d you.

Nothing like this exists in our modern messaging apps.

[…]

People send too many messages. I send too many messages. The first step in making messaging amends is to admit that you, too, are an inconsiderate messaging maniac.

But I’ll never stop, and neither will you. Quick messaging is a utility. It is, in many cases, the most efficient and meaningful form of communication we have. It’s crucial for relationship building, for organizing, for supporting others through hard times. It can be joyful.

[…]

Would something like the Away Message, a relic from an era when we just didn’t message so darn much, actually put up the guardrails we need? Maybe not. But I’m willing to try anything at this point. If we can’t ever get away from messages, at the very least we can create a digital simulacrum of ourselves that appears to be away. What else is the internet for?

Updating our worldviews

I’m reading a book which deals with the Protestant Reformation at the moment. I think for anyone who knows some history, there have been times which have truly been unprecedented; things have changed so quickly that people haven’t been able to keep up.

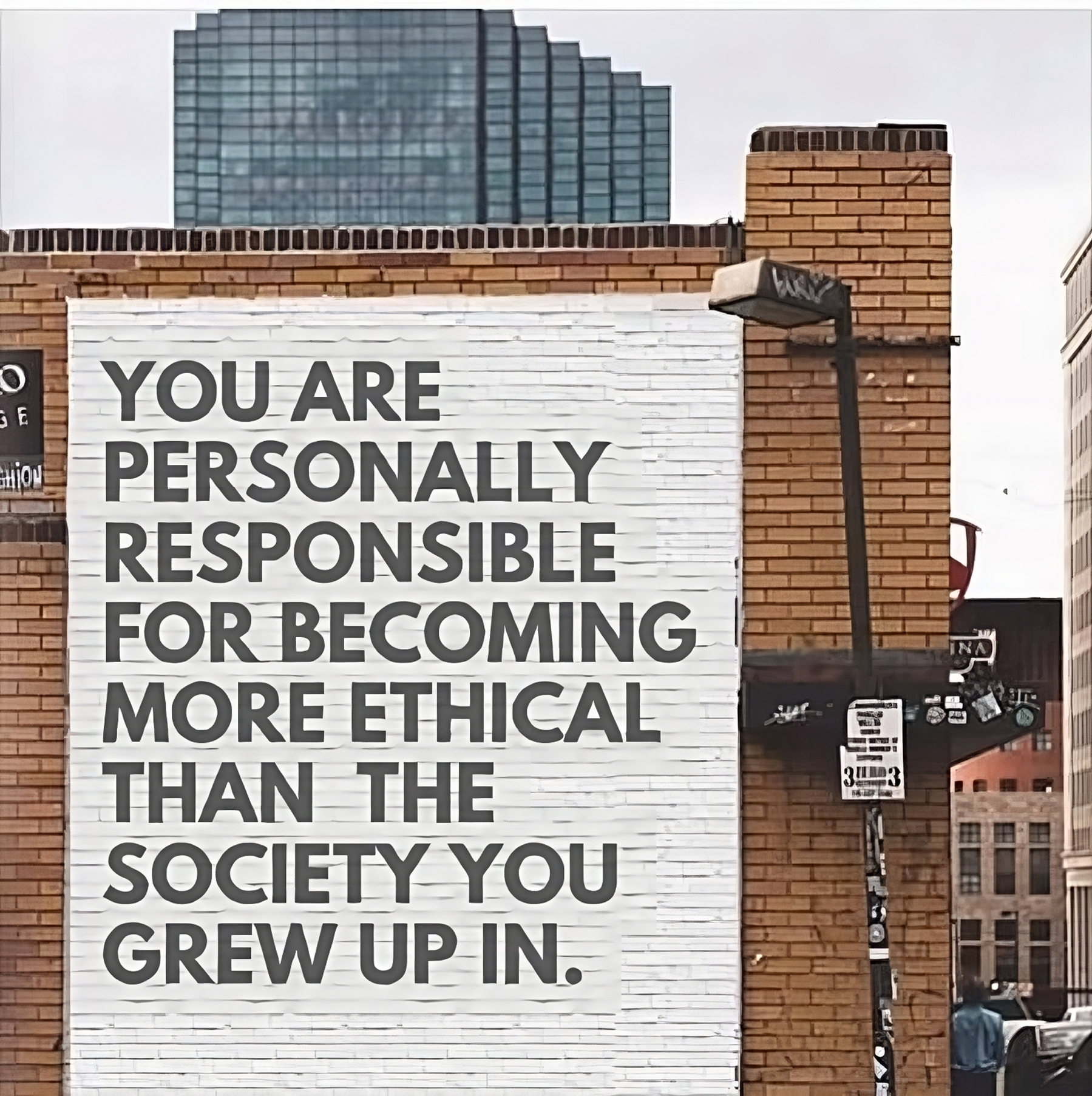

We’re living during a slow, but accelerating, car crash. We do need to update our mental models, for sure. But collectively, and most important at levels which are going to have an impact. Let’s not forget that just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of global emissions.

Those of us with active minds are constantly gardening our worldviews. We adjust our perspectives as events around us unfold, as age and experience inform our received wisdom, as we learn new facts — and as cultural change around us pushes us to think differently. Even in extremely stable and slow-changing societies, there are always some people doing this gardeningSource: Old thinking will break your brain. | Alex SteffenBut this is not a stable society, and today gardening is not enough.

We grew up in societies built upon certain assumptions about how the world works, and how the planet around us should be seen. We now know those assumptions were wrong in profound ways, and in one human lifetime we have altered the climate and biosphere, squandered vast natural riches and destabilized a myriad of systems we depend on. We have made the circumstances of our lives discontinuous with everything that came before us. The societies we live in are now catastrophically unsuited for the planet we’ve made. Yet we still see the planet around us with worldviews formed inside of those societies.

[…]

Seeing with fresh eyes is something we can learn to do. It offers real advantages. At very least, an updated worldview means being able to stand in the surf and face the ocean, to see the waves rolling in, giving us a better shot at not getting plowed and dragged when the next sleeper wave suddenly surges up and hits us.

[…]

Right now, rebuilding our worldviews involves a lot of labor-intensive personal exploration. Being native to now demands finding insight, not just receiving it. It demands teaching ourselves how to learn new things, when both the course of our study and the lessons to be absorbed are complex and constantly evolving. This is a real challenge when we have such busy lives. A lot of people will decide to worry about it later.

[…]

The greatest danger in any work that asks you to think systemically about the future is getting locked into the worldview that made sense to you when you first began, that you built your successful career on.

We all have limited time and energy. Building up an insightful mental model of how the world works takes a lot of both. The pay-off is in the profit and sense of purpose gained from one’s expertise. It is very common, when you’re highly rewarded for a given set of working insights, to commit more to those insights as your career unfolds, to begin even to defend those insights from challenging new perspectives (ones you fear might devalue your intellectual stock in trade). This “sunk-cost expertise” can easily become a set of shackles.

[…]

All this is to say that the very process of worldview-building is undergoing an unprecedented shift. The planetary crisis is swallowing the world we thought we knew, whole, in one great gulp.

What technology means in late capitalism

Anyone familiar with Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle will appreciate this article by Jonathan Crary, author of the short but impressive 24/7 Capitalism.

Crary's argument is that our current status quo depends on a capital-fuelled extractive mikitary-industriiall complex that cannot be sustained. What comes next can't (isn't likely to look like) just a 'Green New Deal' version of it.

Any possible path to a survivable planet will be far more wrenching than most recognize or will openly admit. A crucial layer of the struggle for an equitable society in the years ahead is the creation of social and personal arrangements that abandon the dominance of the market and money over our lives together. This means rejecting our digital isolation, reclaiming time as lived time, rediscovering collective needs, and resisting mounting levels of barbarism, including the cruelty and hatred that emanate from online. Equally important is the task of humbly reconnecting with what remains of a world filled with other species and forms of life. There are innumerable ways in which this may occur and, although unheralded, groups and communities in all parts of the planet are moving ahead with some of these restorative endeavors.

However, many of those who understand the urgency of transitioning to some form of eco-socialism or no-growth post-capitalism carelessly presume that the internet and its current applications and services will somehow persist and function as usual in the future, alongside efforts for a habitable planet and for more egalitarian social arrangements. There is an anachronistic misconception that the internet could simply “change hands,” as if it were a mid-20th-century telecommunications utility, like Western Union or radio and TV stations, which would be put to different uses in a transformed political and economic situation.But the notion that the internet could function independently of the catastrophic operations of global capitalism is one of the stupefying delusions of this moment. They are structurally interwoven, and the dissolution of capitalism, when it happens, will be the end of a market-driven world shaped by the networked technologies of the present.

Of course, there will be means of communication in a post-capitalist world, as there always have been in every society, but they will bear little resemblance to the financialized and militarized networks in which we are entangled today. The many digital devices and services we use now are made possible through unending exacerbation of economic inequality and the accelerated disfiguring of the earth’s biosphere by resource extraction and needless energy consumption.

It's time to accept that centralised social media won't change

A great blog post by Chris Trottier about actually doing something about the problems with centralised social media, by refusing to be a part of it any more.

As an aside, once you see the problem with capitalism mediating every human relationship and interest, you can’t un-see it. For example, I’m extremely hostile to advertising. I really can’t stand it these days.

Centralized social media won't change. No regulatory bodies are coming to the rescue. If you hang around Twitter or Facebook long enough, no benevolent CEO will sprinkle magic pixie dust to make it better.Source: What should we do about toxic social media? | PeerverseAcceptance is no small thing. If you’ve spent years on a social network, investing in relationships, it’s hard to accept that all that effort was a waste. I’m not talking about the people you build friendships with, but the companies and services that connect you. Twitter and Facebook are the nuclear ooze of the Internet, and nothing’s going to make them better.

It’s time to let go. Toxic social media doesn’t care about you, it just wants to exploit you. To them, you’re inventory, a blip in a database.

[…]

Getting rid of toxic social media is about building a future without it. There’s thousands of developers working on an open web, all who are dedicated to building a better Internet. Still, if we want those walled gardens to be dismantled, we must let developers know it’s worth while to code an alternative.

Thus, it's time to accept centralized social media for what it is: it is toxic and won't change. Once you accept this, vote with your feet. Then vote with your wallet.

Cancel Technology

Noah Smith makes a good point in this article that ‘cancel culture’ has always existed, we just called it ‘social ostracism’. The difference is the technology we interact with, and the intended and unintended audiences with which we communicate.

First let’s think about distribution. In the olden days, you could “read the room” and decide whether you were going to get a sympathetic ear before you said something. You knew who you were hanging out with — your relatives, or your coworkers, or your buddies, or your neighbors, or your cell of the Communist Party, etc. On the internet, that’s much less true. On Twitter, anyone can see what you write and retweet it or screenshot it to millions of strangers all over the globe. In a Facebook group, you probably don’t know exactly what kind of others are in the group unless it’s really small. If you put something up on a website, anyone can read it. Etc.Source: It’s not Cancel Culture, it’s Cancel Technology | NoahpinionThe internet also makes it much less hard to maintain private spaces because text can be screenshotted and distributed widely. In the old days, if you said something that would be cancel-worthy outside the group of people you were talking to, it was impossible for someone to verifiably transmit that information outside the group — they could snitch on you, but it would be hearsay and you could deny it. But when you write something down, the text of what you wrote can be screenshotted and distributed widely to people that you didn’t expect to be watching you.

Now, this broad distribution has a number of effects. It makes it a lot harder to get together with your buddies in private and say racist or sexist stuff, because now one of them can betray you with a screenshot. Lots of people are probably pleased with that outcome.

But it also means that everyone who talks on the internet must always worry about their words being shown to someone who’s going to interpret it in an uncharitable way.

[…]

Thus, the internet changes Cancel Culture by massively increasing the number of people who can target you for ostracism. It’s a bit like living in a gossipy small town where you don’t know any of your neighbors — you don’t know who’s going to read what you write, so you don’t know how people are going to take what you say.

Declining trust in society isn't just a 'vibe shift'

This is a wide-ranging and somewhat jumbled article which nevertheless has at its core a key point about the decline in trust in society. That’s not just a ‘vibe shift’ but a more permanent and worrying state of affairs.

Consider the Edelman Trust Barometer. The public relations firm has been conducting an annual global survey measuring public confidence in institutions since 2000. Its 2022 report, which found that distrust is now “society’s default emotion,” recorded a trend of collapsing faith in institutions such as government or media.Source: What You’re Feeling Isn’t A Vibe Shift. It’s Permanent Change. | BuzzFeed News[…]

It’s difficult to imagine how trust in national governments can be repaired. This is not, on the face of it, apocalyptic. The lights are on and the trains run on time, for the most part. But civic trust, the stuff of nation-building, believing that governments are capable of improving one’s life, seems to have dimmed.

Your attention was stolen

I still find it hard to trust Johann Hari’s writing, but this is more introspective and covers a subject that we all know is an issue: attention.

For me, despite being ‘verified’ on Twitter and having what used to be considered a decent number of followers, I’ve deactivated my account. I think it’s for the last time. I’m so much calmer when not using it.

I realised that to heal my attention, it was not enough simply to strip out distractions. That makes you feel good at first – but then it creates a vacuum where all the noise was. I realised I had to fill the vacuum. To do that, I started to think a lot about an area of psychology I had learned about years before – the science of flow states. Almost everyone reading this will have experienced a flow state at some point. It’s when you are doing something meaningful to you, and you really get into it, and time falls away, and your ego seems to vanish, and you find yourself focusing deeply and effortlessly. Flow is the deepest form of attention human beings can offer. But how do we get there?Source: Your attention didn’t collapse. It was stolen | The Guardian

Your accusations are your confessions

I didn’t know Stephen Downes had a political blog. These are his thoughts on cancel culture which, like most of what he says in general, I agree with.

Every time a conservative complains about censorship or ‘cancel culture’ we need to remind ourselves, and to say to them,Source: Cancelled | Leftish“You are the one complaining about cancel culture because you are the one who uses silencing and suppression as political tools to advance your own interests and maintain your own power.

“You are complaining about cancel culture because the people you have always silenced are beginning to have a voice, and they are beginning to say, we won’t be silent any more.

“And when you say the people working against racism and misogyny and oppression are silencing you, that tells us exactly who – and what – you are.”

“Your accusations are your confessions.”

Psychological hibernation

I can’t really remember what life was like before having children. Becoming a parent changes you in ways you can’t describe to non-parents.

Similarly, if we tried to go back in time and explain how the pandemic has changed us, how we’re more susceptible to burnout, less up for meeting with other people, it would be almost impossible to do.

One term that might be useful, however, is ‘psychological hibernation’ — as this article explains.

Was it always like this? Can anyone actually remember what it was like before? For some reason, coming up with an answer to that question is like recalling a boring dream: the more you attempt to remember the details of life before Covid, the quicker it fades, as if it never happened at all.Source: The great Covid social burnout: why are we so exhausted? | New StatesmanIn 2018, a group of psychologists in the Antarctic published a report that may help us understand our current collective exhaustion. The researchers found that the emotional capacity of people who had relocated to the end of the world had been significantly reduced in the time they had been there; participants living in the Antarctic reported feeling duller than usual and less lively. They called this condition “psychological hibernation”. And it’s something many of us will be able to relate to now.

“One of the things that we noticed throughout the pandemic is that people started to enter this phase of psychological hibernation,” said Emma Kavanagh, a psychologist specialising in how people deal with the aftermath of disasters. “Where there’s not many sounds or people or different experiences, it doesn’t require the brain to work at quite the same level. So what you find is that people felt emotionally like everything had just been dialled back. It looks a lot like burnout, symptom wise.” Kavanagh continued: “I think that happened to us all in lockdown, and we are now struggling to adapt to higher levels of stimulus.”

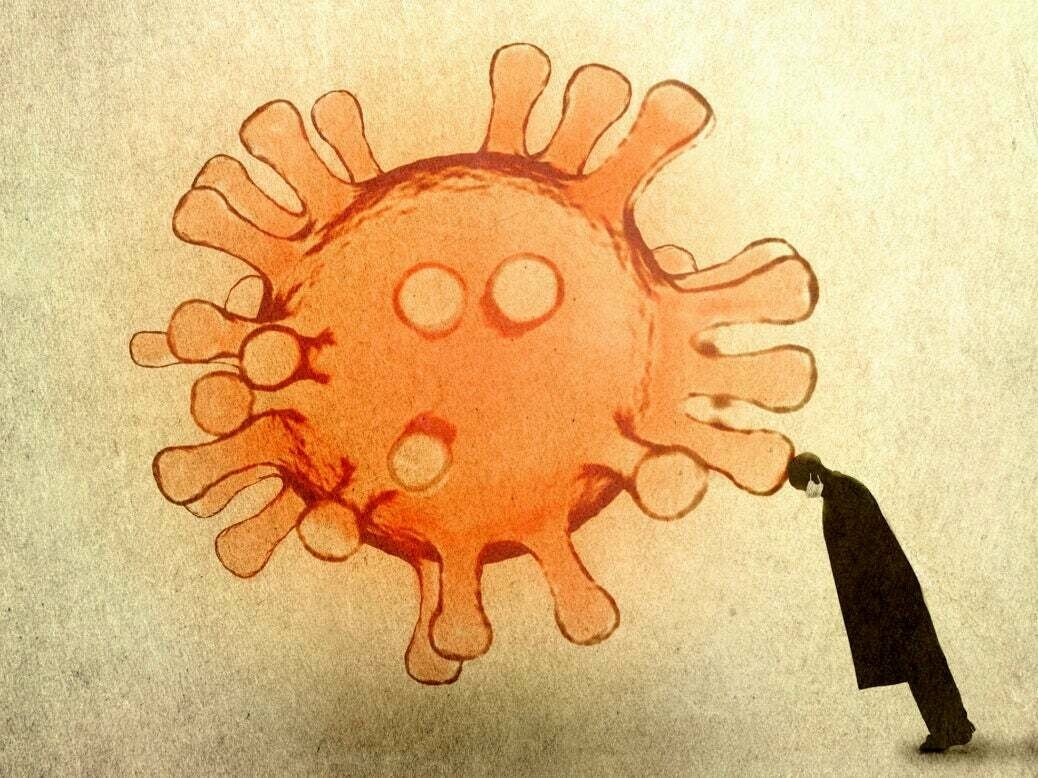

Walking the Covid tightrope

I’m sharing this article mainly for the genius of the accompanying illustration, although it also does a good job of trying to explain an increasing feeling of English exceptionalism.

The results look increasingly alarming. In pubs, in shops, on public transport and in other enclosed spaces where the virus easily spreads, many people are acting as if the pandemic is over – or at least, over for them. Mask-wearing and social distancing have sometimes become so rare that to practise them feels embarrassing.Source: With Covid infections rising, the Tories are conducting a deadly social experiment | The GuardianMeanwhile, England has become one of the worst places for infections in the world, despite a high degree of vaccination by global standards. Case numbers, hospitalisations and deaths are all rising, and are already much higher than in other western European countries that have kept measures such as indoor mask-wearing compulsory, and where compliance with such rules has remained strong. What does England’s failure to control the virus through “personal responsibility” say about our society?

It’s tempting to start by generalising about national character, and how the supposed individualism of the English has become selfishness after half a century of frequent rightwing government and fragmentation in our lives and culture. There may be some truth in that. But national character is not a very solid concept, weakened by all the differences within countries and all the similarities that span continents. Thanks to globalisation, all European societies have been affected by the same atomising forces. England’s lack of altruism during the pandemic can’t just be blamed on neoliberalism.

Other elements of our recent history may also explain it. England likes to think of itself as a stable country, yet since the 2008 financial crisis it has endured a more protracted period of economic, social and political turmoil than most European countries. The desire to return to some kind of normality may be especially strong here; taking proper anti-Covid precautions would be an acknowledgement that we cannot do that.

Kith and kin

This is a great article about how the internet was going to save us from TV and now we’re looking for something to save us from the internet. What we actually need are stronger and deeper relationships with the people around us — our kith and kin.

We are conditioned to care about kin, to take life’s meaning from the relationships with those we know and love. But the psychological experience of fame, like a virus invading a cell, takes all of the mechanisms for human relations and puts them to work seeking more fame. In fact, this fundamental paradox—the pursuit through fame of a thing that fame cannot provide—is more or less the story of Donald Trump’s life: wanting recognition, instead getting attention, and then becoming addicted to attention itself, because he can’t quite understand the difference, even though deep in his psyche there’s a howling vortex that fame can never fill.Source: On the Internet, We’re Always Famous | The New YorkerThis is why famous people as a rule are obsessed with what people say about them and stew and rage and rant about it. I can tell you that a thousand kind words from strangers will bounce off you, while a single harsh criticism will linger. And, if you pay attention, you’ll find all kinds of people—but particularly, quite often, famous people—having public fits on social media, at any time of the day or night. You might find Kevin Durant, one of the greatest basketball players on the planet, possibly in the history of the game—a multimillionaire who is better at the thing he does than almost any other person will ever be at anything—in the D.M.s of some twenty something fan who’s talking trash about his free-agency decisions. Not just once—routinely! And he’s not the only one at all.

There’s no reason, really, for anyone to care about the inner turmoil of the famous. But I’ve come to believe that, in the Internet age, the psychologically destabilizing experience of fame is coming for everyone. Everyone is losing their minds online because the combination of mass fame and mass surveillance increasingly channels our most basic impulses—toward loving and being loved, caring for and being cared for, getting the people we know to laugh at our jokes—into the project of impressing strangers, a project that cannot, by definition, sate our desires but feels close enough to real human connection that we cannot but pursue it in ever more compulsive ways.

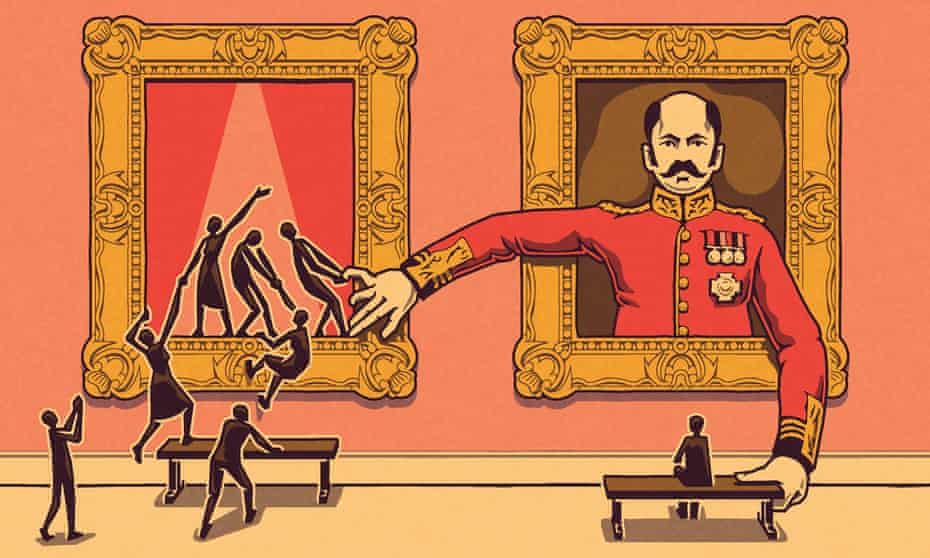

Culture is in a state of constant flux

My parents, the son of a factory worker and assistant baker and the daughter of domestic servants, were both the first in their families to go to university. As such, they wanted to ensure that their children, my sister and I, knew our way around ‘culture’.

Hence, for me, a childhood punctuated not only piano lessons and visits to National Trust properties but visits to the cheapest seats at the theatre to see ballets and plays. In their mind, at least back then, there was ‘Culture’ (with a capital ‘C’) to which we had to be introduced.

As Kojo Koram from the School of Law at Birkbeck, University of London, writes, however, culture is something that is continually remade by the people living it. These different conceptions mark the boundaries of the culture wars currently being played out in British politics and society.

In the 1960s and 70s, when [Stuart] Hall was writing, most British intellectuals dismissed the new mass culture taking hold in the country as a passing fad that did not deserve the attention given to Shakespeare, Elgar or Hogarth. But Hall recognised how it offered an increasingly multicultural British population the opportunity to interpret and experience life as it was lived on the ground. Rather than seeing culture as something fixed and unchanging that needed constant protection, Hall saw it as something that underwent “constant transformation” and was always being made and remade by the people living it, a moving force that perpetually created new identities.Source: Here’s what the right gets wrong about culture: it’s not a monument, but a living thing | The GuardianIt is no coincidence that so many of the primary battlegrounds where today’s culture wars are being staged are the elite institutions that represent a traditional British hierarchy: stately homes, Oxford university common rooms, the Last Night of the Proms. To culture warriors on the right, these institutions best represent Britain’s national culture as a whole. That they are exclusive is part of their appeal: when culture is defined as something that only a few people can access or control, its preservation is best entrusted to high-ranking authorities.

The Puritan Class

Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie reflects on sanctimonious social media:

In certain young people today... I notice what I find increasingly troubling: a cold-blooded grasping, a hunger to take and take and take, but never give; a massive sense of entitlement; an inability to show gratitude; an ease with dishonesty and pretension and selfishness that is couched in the language of self-care; an expectation always to be helped and rewarded no matter whether deserving or not; language that is slick and sleek but with little emotional intelligence; an astonishing level of self-absorption; an unrealistic expectation of puritanism from others; an over-inflated sense of ability, or of talent where there is any at all; an inability to apologize, truly and fully, without justifications; a passionate performance of virtue that is well executed in the public space of Twitter but not in the intimate space of friendship.Source: IT IS OBSCENE: A TRUE REFLECTION IN THREE PARTS | Chimamanda.comI find it obscene.

There are many social-media-savvy people who are choking on sanctimony and lacking in compassion, who can fluidly pontificate on Twitter about kindness but are unable to actually show kindness. People whose social media lives are case studies in emotional aridity. People for whom friendship, and its expectations of loyalty and compassion and support, no longer matter. People who claim to love literature – the messy stories of our humanity – but are also monomaniacally obsessed with whatever is the prevailing ideological orthodoxy. People who demand that you denounce your friends for flimsy reasons in order to remain a member of the chosen puritan class.

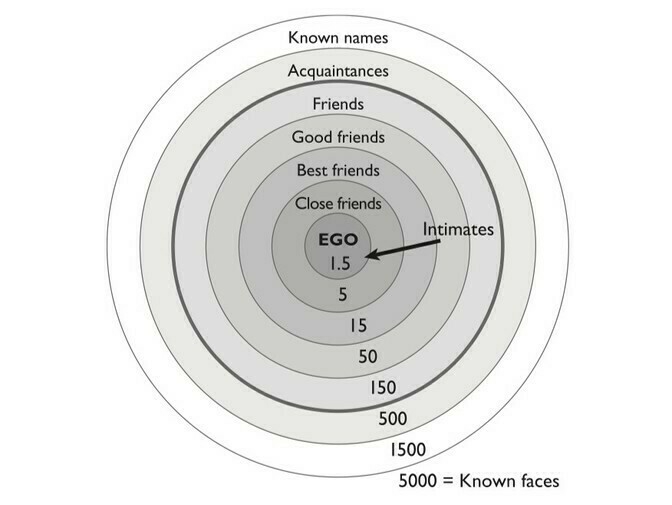

Dunbar's friendship circles

This is interesting: the number of people say they have in different friendship ‘circles’. Extroverts tend to have more than introverts.

Those numbers are aspirational, right? 😅

Dunbar’s number really isn’t a single number. It should be a series of numbers. When collecting data on personal friendships, we asked everybody to list out everybody in their friendship circles, when they last saw them, and how emotionally close they felt to them on a simple numerical scale. Relationships turned out to be highly structured in the sense that people didn’t see or contact everybody in their social network equally. The network was very clumpy.Source: Robin Dunbar Explains Humans' Circles of Friendship | The AtlanticThe distribution of the data formed a series of layers, with each outer layer including everybody in the inner layer. Each layer is three times the size of the layer directly preceding it: 5; 15; 50; 150; 500; 1,500; 5,000.

The innermost layer of 1.5 is [the most intimate]; clearly that has to do with your romantic relationships. The next layer of five is your shoulders-to-cry-on friendships. They are the ones who will drop everything to support us when our world falls apart. The 15 layer includes the previous five, and your core social partners. They are our main social companions, so they provide the context for having fun times. They also provide the main circle for exchange of child care. We trust them enough to leave our children with them. The next layer up, at 50, is your big-weekend-barbecue people. And the 150 layer is your weddings and funerals group who would come to your once-in-a-lifetime event.

The layers come about primarily because the time we have for social interaction is not infinite. You have to decide how to invest that time, bearing in mind that the strength of relationships is directly correlated with how much time and effort we give them.

Anti-social media

As I mentioned on my blog recently, I sometimes feel a strong pull to ‘nuke’ everything and start over again. With Twitter, I actually did this back in 2017, deleting 77.5k spanning 10 years. They now auto-delete every three months.

This article is based on a survey that BuzzFeed News carried out which revealed a shift in attitude, especially among younger people, to social media. (I think we need a different name for social media that any member of the public can see and those that are private to your followers by default?)

Trying to live in the moment isn’t just difficult because so many of us are prone to documenting our days, our phones and social media apps are also intent on continually resurfacing aspects of our past. While some respondents said they were happy to have the reminders (one mentioned loving comments popping up from her late grandmother — “she was hilarious!”), others had more mixed or flat-out negative feelings.Source: COVID Made People Delete Facebook And Instagram | BuzzFeed NewsSeeing versions of ourselves from 5 or 10 years ago can be cringey, which is why a lot of respondents have purged old posts altogether. Ashlee Burke from Boston, who’s in her late 20s, said she made her old Facebook photo albums private because they’re embarrassing, not because they showed any illegal activity or anything — “unless it’s illegal to be the most embarrassing teenager on the face of the Earth.”

When we ask for advice we are usually looking for an accomplice

🏡 What can we learn from the great working-from-home experiment? — "A few knowledge jobs, such as IT support, are properly systematised to allow focused work without endless ad hoc emails. [Cal] Newport believes that others will follow once we all wise up. Or we may find that certain kinds of knowledge work are too unruly to systematise. Improvisation will remain the only mode of working — and, for that, face-to-face contact seems essential."

I disagree with this, having spent almost a decade doing creative, improvisational work, mostly from my home office.

✊ They left Mozilla to make the internet better. Now they’re spreading its gospel for a new generation. — "Plenty of older tech companies spawned networks of industry leaders. Mozilla has, too, only it's a different kind of group: a collection of values-driven engineers, marketers, program managers and founders. Most of them share a common story: Looking for a sense of purpose in tech, they took a financial hit for the chance to become part of the company's cult-like obsession with openness and privacy. Though the company had its flaws, they left feeling deep loyalty to the mission, and a sense of betrayal from those who went on to work for the tech giants Mozilla has been battling. "

Some companies act as a filter for a certain type of person. Mozilla is like that, and while I was there I worked with some of the most ethical and awesome people I've ever come across.

🤪 Why It’s Usually Crazier Than You Expect — "The idea that people like (or hate) what other people like (or hate) is important, because it lets small ideas grow bigger than you’d guess if you assume everything is ranked by quality alone. Social momentum is hard to model on a spreadsheet, so it’s hard to predict or think about in terms that seem rational. But it’s so powerful."

The standard economic model is that people act in their individual and group self-interest. But humans are much more complicated than that.

🎓 Academics Are Really, Really Worried About Their Freedom — "Some will process this as a kind of whining, supposing that all we should really be concerned about is whether people are outright dismissed. However, elsewhere a hostile work environment is considered a breach of civil rights, and as one correspondent wrote, “It isn’t just fear of firing that motivates professors and grad students to be quiet. It is a desire to have friends, to be part of a community. This is a fundamental part of human psychology. Indeed, experiments examining the effects of ostracism highlight what a powerful existential threat it is to be ignored, excluded, or rejected. This has been documented at the neurological level. Ostracism is a form of social death. It is a very potent threat.”

Given how conservative humanity has been for the past tens of thousands of years, and given how radical we need to be to fix the world, I don't have lots of sympathy with this view. Especially when tenured professors have the kind of job security most people can only dream of.

👩💻 Where we are with digital learning adoption — "We should have less big bang summative exams sat in big rooms with invigilators, there are plenty of alternatives. Online assessment systems can at least allow for typing, which is more authentic, and why not also speaking, and drawing? And in the scenarios where an unseen timed assessment is the only option and it has to be online: sometimes proctoring might be useful. It shouldn’t be the default. But it might have a place, sometimes."

I'm sharing this to +1,000,000 Amber's suggestion that, for assessment purposes, speaking and drawing should be as authentic as typing and writing.

Quotation-as-title by Marquis de la Grange. Image: Changing the Letter, 1908, by Joseph Edward Southall

Better to write for yourself and have no public, than to write for the public and have no self

📚 Bookshelf designs as unique as you are: Part 2 — "Stuffing all your favorite novels into a single space without damaging any of them, and making sure the whole affair looks presentable as well? Now, that’s a tough task. So, we’ve rounded up some super cool, functional and not to mention aesthetically pleasing bookshelf designs for you to store your paperback companions in!"

📱 How to overcome Phone Addiction [Solutions + Research] — "Phone addiction goes hand in hand with anxiety and that anxiety often lowers the motivation to engage with people in real life. This is a huge problem because re-connecting with people in the offline world is a solution that improves the quality of life. The unnecessary drop in motivation because of addiction makes it that much harder to maintain social health."

⚙️ From Tech Critique to Ways of Living — "This technological enframing of human life, says Heidegger, first “endanger[s] man in his relationship to himself and to everything that is” and then, beyond that, “banishes” us from our home. And that is a great, great peril."

🎨 Finding time for creativity will give you respite from worries — "According to one study examining the links between art and health, a cost-benefit analysis showed a 37% drop in GP consultation rates and a 27% reduction in hospital admissions when patients were involved in creative pursuits. Other studies have found similar results. For example, when people were asked to write about a trauma for 15 minutes a day, it resulted in fewer subsequent visits to the doctor, compared to a control group."

🧑🤝🧑 For psychologists, the pandemic has shown people’s capacity for cooperation — "In short, what we have seen is a psychology of collective resilience supplanting a psychology of individual frailty. Such a shift has profound implications for the relationship between the citizen and the state. For the role of the state becomes less a matter of substituting for the deficiencies of the individual and more to do with scaffolding and supporting communal self-organisation."

Quotation-as-title by Cyril Connolly. Image from top-linked post.

At times, our strengths propel us so far forward we can no longer endure our weaknesses and perish from them

🤑 We can’t have billionaires and stop climate change

📹 How to make video calls almost as good as face-to-face

⏱️ How to encourage your team to launch an MVP first

☑️ Now you can enforce your privacy rights with a single browser tick

Quotation-as-title from Nietzsche. Image from top-linked post.