- You Shouldn’t Have to Be Good at Your Job (GEN) — "This is how the 1% justifies itself. They are not simply the best in terms of income, but in terms of humanity itself. They’re the people who get invited into the escape pods when the mega-asteroid is about to hit. They don’t want a fucking thing to do with the rest of the population and, in fact, they have exploited global economic models to suss out who deserves to be among them and who deserves to be obsolete. And, thanks to lax governments far and wide, they’re free to practice their own mass experiments in forced Darwinism. You currently have the privilege of witnessing a worm’s-eye view of this great culling. Fun, isn’t it?"

- We've spent the decade letting our tech define us. It's out of control (The Guardian) — "There is a way out, but it will mean abandoning our fear and contempt for those we have become convinced are our enemies. No one is in charge of this, and no amount of social science or monetary policy can correct for what is ultimately a spiritual deficit. We have surrendered to digital platforms that look at human individuality and variance as “noise” to be corrected, rather than signal to be cherished. Our leading technologists increasingly see human beings as a problem, and technology as the solution – and they use our behavior on their platforms as evidence of our essentially flawed nature."

- How headphones are changing the sound of music (Quartz) — "Another way headphones are changing music is in the production of bass-heavy music. Harding explains that on small speakers, like headphones or those in a laptop, low frequencies are harder to hear than when blasted from the big speakers you might encounter at a concert venue or club. If you ever wondered why the bass feels so powerful when you are out dancing, that’s why. In order for the bass to be heard well on headphones, music producers have to boost bass frequencies in the higher range, the part of the sound spectrum that small speakers handle well."

- The False Promise of Morning Routines (The Atlantic) — "Goat milk or no goat milk, the move toward ritualized morning self-care can seem like merely a palliative attempt to improve work-life balance.It makes sense to wake up 30 minutes earlier than usual because you want to fit in some yoga, an activity that you enjoy. But something sinister seems to be going on if you feel that you have to wake up 30 minutes earlier than usual to improve your well-being, so that you can also work 60 hours a week, cook dinner, run errands, and spend time with your family."

- Giant surveillance balloons are lurking at the edge of space (Ars Technica) — "The idea of a constellation of stratospheric balloons isn’t new—the US military floated the idea back in the ’90s—but technology has finally matured to the point that they’re actually possible. World View’s December launch marks the first time the company has had more than one balloon in the air at a time, if only for a few days. By the time you’re reading this, its other stratollite will have returned to the surface under a steerable parachute after nearly seven weeks in the stratosphere."

- The Unexpected Philosophy Icelanders Live By (BBC Travel) — "Maybe it makes sense, then, that in a place where people were – and still are – so often at the mercy of the weather, the land and the island’s unique geological forces, they’ve learned to give up control, leave things to fate and hope for the best. For these stoic and even-tempered Icelanders, þetta reddast is less a starry-eyed refusal to deal with problems and more an admission that sometimes you must make the best of the hand you’ve been dealt."

- What Happens When Your Career Becomes Your Whole Identity (HBR) — "While identifying closely with your career isn’t necessarily bad, it makes you vulnerable to a painful identity crisis if you burn out, get laid off, or retire. Individuals in these situations frequently suffer anxiety, depression, and despair. By claiming back some time for yourself and diversifying your activities and relationships, you can build a more balanced and robust identity in line with your values."

- Having fun is a virtue, not a guilty pleasure (Quartz) — "There are also, though, many high-status workers who can easily afford to take a break, but opt instead to toil relentlessly. Such widespread workaholism in part reflects the misguided notion that having fun is somehow an indulgence, an act of absconding from proper respectable behavior, rather than embracement of life. "

- It’s Time to Get Personal (Laura Kalbag) — "As designers and developers, it’s easy to accept the status quo. The big tech platforms already exist and are easy to use. There are so many decisions to be made as part of our work, we tend to just go with what’s popular and convenient. But those little decisions can have a big impact, especially on the people using what we build."

- The 100 Worst Ed-Tech Debacles of the Decade (Hack Education) — "Oh yes, I’m sure you can come up with some rousing successes and some triumphant moments that made you thrilled about the 2010s and that give you hope for “the future of education.” Good for you. But that’s not my job. (And honestly, it’s probably not your job either.)"

- Why so many Japanese children refuse to go to school (BBC News) — "Many schools in Japan control every aspect of their pupils' appearance, forcing pupils to dye their brown hair black, or not allowing pupils to wear tights or coats, even in cold weather. In some cases they even decide on the colour of pupils' underwear. "

- The real scam of ‘influencer’ (Seth Godin) — "And a bigger part is that the things you need to do to be popular (the only metric the platforms share) aren’t the things you’d be doing if you were trying to be effective, or grounded, or proud of the work you’re doing."

- What your laptop-holding position says about you (Quartz at Work) — "Over the past few weeks, we’ve been observing Quartzians in their natural habitat and have tried to make sense of their odd office rituals in porting their laptops from one meeting to the next."

- Meritocracy doesn’t exist, and believing it does is bad for you (Fast Company) — "Simply holding meritocracy as a value seems to promote discriminatory behavior."

- Your Body as a Map (Sapiens) — "Reading the human body canvas is much like reading a map. But since we are social beings in complex contemporary situations, the “legend” changes depending on when and where a person looks at the map."

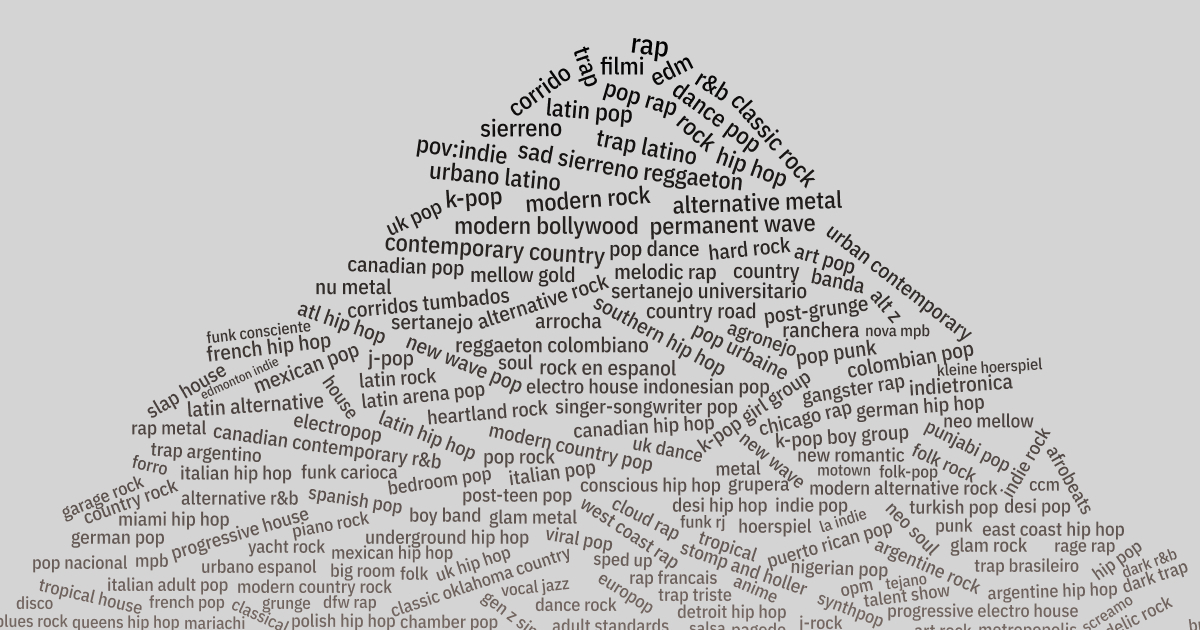

Dynamic ontologies and music genres

As a music lover and someone who has more than a passing interest in dynamic ontologies, I found this analysis of Spotify’s changing categorisation of genres fascinating.

Spotify Unwrapped shows users their most-streamed artists, tracks, and genres at the end of the year. But what if you want to find out at another time? I just had a look at Chosic, which told me that my main ‘parent genres’ are Hip hop, Pop, and Electronic. My top sub-genres are trip hop, downtempo, and electronica.

All of the pushback against genre classifications are valid, whether that's inventing escape room and stomp & holler of what qualifies as r&b vs. pop.Source: You should look at this chart about music genres | pudding.coolBut I still think an always-updating catalog of 6,000 genres is groundbreaking.

I see this effort in the same way I see taxonomy: technically accurate, colloquially useless.

For centuries we had generic names to identify animals, such as “fish.” Everything from squid to crabs (and obviously jellyfish) were lumped into the same “fish” bucket.

But on closer inspection, most of these animals were not related at all. In a research context, scientists have draw boundaries between animals that we mindlessly lumped together.

Similarly, the genre database adds much needed detail to broad categories, like hip hop and rock. For musicologists, it’s an anthropological gold mine. And for Spotify, it likely helps them to better profile their users' music tastes.

But these genres don’t necessarily work in casual conversation: you can describe your music taste as indie, even if, technically, Spotify says it’s escape room. The same goes for biology: people should call figs a fruit, even though it’s technically an inverted flower.

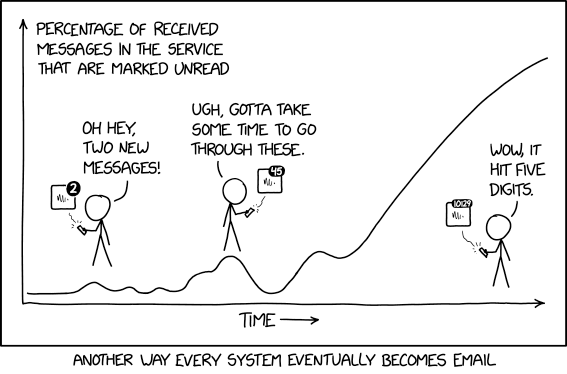

Songs are not meme stocks

Remember NFTs? This article in The Guardian will help remind you of the heady days of early 2022 when digital images of monkeys were apparently extremely valuable. That article ends with a question: “what will the next NFT be? When will it drop? How much money will normal people end up spending on it?”

Here’s one answer: owning a slice of your favourite song. Or perhaps a popular song. Or an up-and-coming song. It’s essentially applying capitalism at the very smallest level possible, and treating cultural artifacts as commodities.

The article below in WIRED discusses a platform which offers this as a service. It’s a terrible idea on many levels, not least because, as we’ve seen recently, AI-generated music is tearing fandoms apart. I’ll sit this one out, thanks.

Imagine a retirement portfolio stocked with Rihanna hits, or a college fund fueled by Taylor Swift’s 1989. In a post-GameStop, post-NFT-mania world, it sounds plausible enough. Wholesome, even.Source: The Next Meme Stock? Owning a Slice of Your Favorite Song | WIREDA new music royalties marketplace, Jkbx (pronounced “jukebox”), launched this month and plans to officially open for trading later this year. It has filed an application with the US Securities and Exchange Commission and is waiting for notice that the SEC has qualified its offerings. As long as that goes according to plan, Jkbx—god, why no vowels?—will allow fans to buy “royalty shares,” or fractionalized portions of royalties, fees, and other income associated with a particular song. Prices are within reach of regular people. One share of composition royalties for Beyoncé’s “Halo,” for example, is $28.61. You could also buy a slice of the song’s sound recording royalties for the same price.

[…]

Jkbx is debuting with some big-name slices, and is led by a guy with a good track record. “They are very sophisticated,” Round Hill Music founder and CEO Josh Gruss says. “The real deal.” Others agree. “We think they are going to be successful,” Hipgnosis Songs CEO and founder Merck Mercuriadis says.

Still, plenty of industry analysts and insiders view Jkbx, and the larger world of royalty trading, warily. “I think there are going to be very modest levels of return,” says Serona Elton, a music industry professor at the University of Miami.

“There is skepticism about how good of an alternative investment strategy something like this is,” musician and data analyst Chris Dalla Riva says.

“I don’t understand why people keep trying to spin this idea up,” adds producer and music tech researcher Yung Spielburg. “I just don’t get it.”

Piracy and the art of cultural archiving

Shortly before Daft Punk’s album Discovery was released, I managed to download a version of it which must have been exfiltrated from the studio. It was subtly different to the version that was released and, to be honest, I preferred it. Sadly, I’ve long since lost the MP3s, and the chance of me finding anything other than the official version these days is minimal.

This article is about the preservation of music, movies, and books. What copyright maximalists don’t realise is that piracy is actually amazing at ensuring that cultural diversity flourishes and is preserved. It’s definitely worth a read.

(It’s also interesting to me how this intersects what I posted earlier about AI-generated music and fandom, because both intersect with ‘official’ narratives and our current understanding of copyright.)

"Your local bookseller cannot creep into your home in the middle of the night and reclaim the contents of your bookshelf," the legal scholars Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz observe in their 2016 book The End of Ownership. "But Amazon exercises a very different kind of practical power over your digital library. Your Kindle runs software written by Amazon, and it features a persistent network connection. That means Amazon can send it instructions—to delete a book or even replace it with a new version—without any intervention from you." The potential for mischief was clear as early as 2009, when someone started selling bootleg Kindle editions of George Orwell's 1984 and Amazon reacted by dispatching even some purchased copies to the memory hole.Source: Online Outlaws Preserve the History of Music, Movies, and Books | ReasonThe fearful mood intensifies whenever politics enters the picture. When books by Agatha Christie, Roald Dahl, and other long-dead authors were reedited to reflect what are said to be “contemporary sensitivities,” many e-books were automatically updated even for readers who had bought them long before. During the George Floyd protests of 2020, several streaming services, unable to stop the abusive policing that set off the unrest, decided instead to edit or eliminate TV episodes where characters appeared in blackface. (This wasn’t an anti-racist gesture so much as a cargo-cult copy of an anti-racist gesture—an elaborate imitation built without figuring out the functions of the component parts—and so it mostly affected shows that had presented blackface with obvious disapproval.) Several songs with words that might offend listeners have gone missing from Spotify or (as with Lizzo’s “Grrrls,” which originally included the term spaz) were replaced with new versions.

Every time news breaks of one of these deletions, a refrain echoes online: Buy physical media! The internet is too impermanent, the argument goes: The real cultural cornucopia was in the outside world.

As is often the case with nostalgia, this leaves out a lot. We still have access to far more media than we did in the days before the mass internet. Yes, this includes that politically controversial material: It takes less than a minute to dig up the unredacted version of “Grrrls” on YouTube (just search for lizzo grrrls spaz), and it’s not hard to find material that was withdrawn from circulation long before the internet era. (I’m told the ’90s were a less politically correct time than today, but back then you needed to track down a bootleg DVD or videotape if you were curious about Song of the South. Now it’s posted on the Internet Archive.) It’s too easy to take the internet’s riches for granted and to forget how much was inaccessible just a few decades ago.

But while we shouldn’t want to return to those pre-web days, there’s something to be said for that online-offline hybrid space where my old tape-trading network dwelled—if not as a world to recreate, then as a way to think about cultural preservation. And there’s something to be said for the bootleggers and pirates. Whether or not they mean to do it, they’re salvaging pieces of our heritage.

Fandom and AI generated music

If you haven’t discovered AI-generated songs by your favourite artists, then you’re missing a trick. Try I’m a Barbie Girl by Johnny Cash, for example, or Skyfall by Freddie Mercury. Amazing stuff.

This article is about the fandom around artists such as One Direction and Harry Styles, who are paying hard-earned real money for ‘leaks’ which may or may not be AI-generated music. No-one can tell the difference.

Discord communities within the Harry Styles and One Direction fandom are tearing themselves apart over “leaked snippets” of supposed demo songs that may or may not be AI-generated and are being sold to superfans for hundreds of dollars each.Source: The Specter of AI-Generated ‘Leaked Songs’ Is Tearing the Harry Styles Fandom Apart | 404 MediaThe controversy has turned into a days-long crowdsourced investigation and communitywide obsession, in which no one is really sure what’s real, what’s fake, whether they’re being scammed, or who or what made the songs that they’re listening to.

Over the last few weeks, a flurry of Harry Styles and One Direction snippets—which are short samples of a track designed to prove legitimacy so people will pay of the full thing—have begun popping up on YouTube, TikTok, and, most importantly, Discord, where they are being sold. The problem is no one can tell which, if any, of the songs are real, including AI-analysis companies who listened to the tracks for 404 Media.

You can‘t ruminate and listen at the same time

David Cain at Raptitude has a post which is somewhat bizarrely entitled 10 Things I Want to Communicate to the Human Species Before I Die. The first point is about shopping trolleys, so I’m not sure how tongue-in-cheek it all is.

Anyway, without saying whether I agree or disagree with any of the other statements, I want to draw attention to the last one. Ruminating is a complete waste of time, and as someone susceptible to it I want to +1 the advice to get out of your head and listen if you’re succumbing to it.

For me, that often means listening to my iPod in the early hours of the morning while lying sleepless in bed. But it can mean listening to other people, or just your surroundings.

The tendency of the modern human is to live in their head — almost perpetually monologuing and forecasting and rehashing. This is a seldom-helpful habit most of us reinforce constantly by tumbling along with its momentum. You can weaken the grip of the ruminative mind by frequently taking a few seconds to be quiet and listen to your surroundings. Doing this reveals something interesting: when you actively use your attention for listening (or in any other intentional way) it cannot be used for more rumination. Each time you do this, the gravity of the monologuing mind weakens. If even a fraction of the population learned how to perforate their ongoing ruminative thought-mill like this, it might be a different world.Source: 10 Things I Want to Communicate to the Human Species Before I Die | Raptitude

An urgency to somehow bend the algorithms

The album ‘Homework’ by Daft Punk came out in 1997 when I was 16 years old. That’s the same age as my son is now. I think it’s fair to say that it changed my life.

When I worked in HMV as a student, I used my access to the huge database to discover and order in rare Japan-only releases of Daft Punk’s music. I also discovered music that the duo behind Daft Punk, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo, released on their own labels.

I was sad when I learned that Daft Punk was to be no more, but reading this interview with Thomas Bangalter in The Guardian helps make sense. I think it’s particularly important in life not to become a caricature of yourself. For Bangalter going from scoring a film like Irréversible to ballet couldn’t be more different, really.

Did the future lose its allure at some point? “It’s interesting,” he ponders. “You either have the content or the form. Every artist wants to create their own little revolution and try to do things that haven’t been done. That’s kind of the punk aspect. But you ultimately become a caricature of yourself once you succeed.” The point, he says, is to do something different every time. “It works in opposition. These robots, they’re like the glorification of technology. But even in 2005, when we made this film Electroma, they wanted to become human. It’s human nature – the grass is always greener on the other side.”Source: Up all night to get jeté! Thomas Bangalter on hanging up his Daft Punk helmet – and leaping into ballet | The Guardian[…]

Where does Bangalter feel Daft Punk’s influence now? “There used to be a lot of barriers between genres of music. I was hopeful there was a possibility to break these. That was part of the message of what we did musically.” Pop tribalism is indeed over, and while that can’t be credited to Daft Punk alone – piracy, streaming and three decades of internet did their bit – his hunch was once again correct.

“In some way the world is much more polarised now, but not really musically – musically there is this ability to mix and match and create levels of conflicting aesthetics or clashing ideas. I just hope that the tolerance existing right now in music will exist more in society as well.” The defecting robot has one more warning: “Now there is an urgency to somehow bend the algorithms.”

Nick Cave's plans for 2023

The artist Nick Cave has a (newsletter? blog?) called The Red Hand Files in which he answers questions from his fans. Somebody pointed me towards a recent post where he talks about his aim to write and record a new album in 2023.

I love the way he talks about the creative process, and how mysterious it is.

My plan for this year is to make a new record with the Bad Seeds. This is both good news and bad news. Good news because who doesn’t want a new Bad Seeds record? Bad news because I’ve got to write the bloody thing.Source: Nick Cave - The Red Hand Files - Issue #217[…]

Writing lyrics is the pits. It’s like jumping for frogs, Fred. It’s the shits. It’s the bogs. It actually hurts. It comes in spurts, but few and far between. There is something obscene about the whole affair. Like crimes that rhyme. I hope this doesn’t last long. I’m actually scared. But it always does. Last long. To write a song. You hope to God there is something left. You are bereft. I’m going to stop this letter. It isn’t making things better. It’s like flogging a dead horse. Worse. It’s a hearse. A hearse of dead verse. Dead, Fred. Dead.

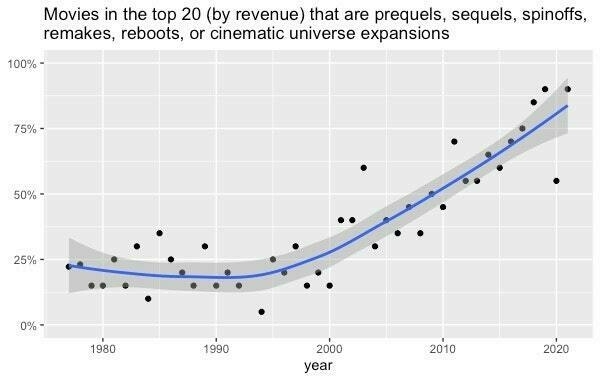

Popular culture has become an endless parade of sequels

Once you start recognising colour schemes and sound effects, every new film ends up looking and sounding the same.

Yes, I’m getting old, but as Adam Mastroianni from Experimental History explains, there’s shifts happening in everything from books to video games.

The problem isn’t that the mean has decreased. It’s that the variance has shrunk. Movies, TV, music, books, and video games should expand our consciousness, jumpstart our imaginations, and introduce us to new worlds and stories and feelings. They should alienate us sometimes, or make us mad, or make us think. But they can’t do any of that if they only feed us sequels and spinoffs. It’s like eating macaroni and cheese every single night forever: it may be comfortable, but eventually you’re going to get scurvy.Source: Pop Culture Has Become an Oligopoly | Experimental History[…]

Fortunately, there’s a cure for our cultural anemia. While the top of the charts has been oligopolized, the bottom remains a vibrant anarchy. There are weird books and funky movies and bangers from across the sea. Two of the most interesting video games of the past decade put you in the role of an immigration officer and an insurance claims adjuster. Every strange thing, wonderful and terrible, is available to you, but they’ll die out if you don’t nourish them with your attention. Finding them takes some foraging and digging, and then you’ll have to stomach some very odd, unfamiliar flavors. That’s good. Learning to like unfamiliar things is one of the noblest human pursuits; it builds our empathy for unfamiliar people. And it kindles that delicate, precious fire inside us––without it, we might as well be algorithms. Humankind does not live on bread alone, nor can our spirits long survive on a diet of reruns.

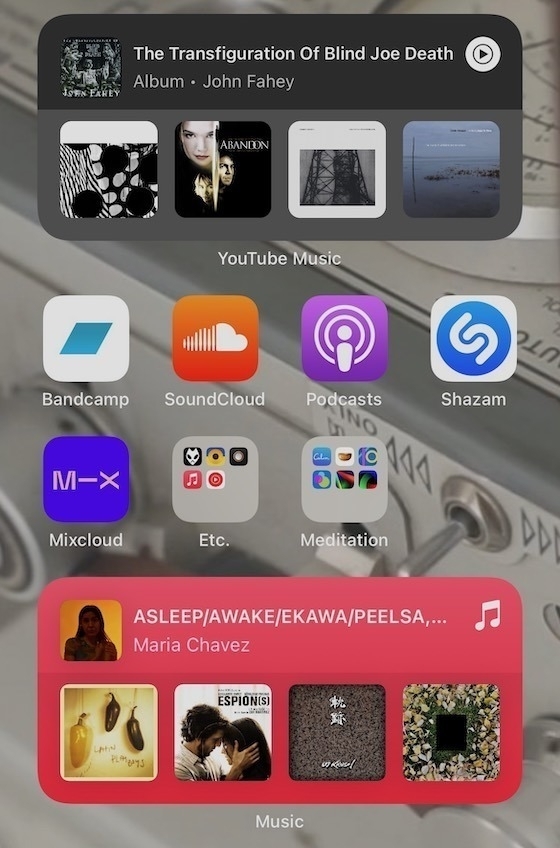

Dedicated portable digital media players and central listening devices

I listen to music. A lot. In fact, I’m listening while I write this (Busker Flow by Kofi Stone). This absolutely rinses my phone battery unless it’s plugged in, or if I’m playing via one of the smart speakers in every room of our house.

I’ve considered buying a dedicated digital media player, specifically one of the Sony Walkman series. But even the reasonably-priced ones are almost the cost of a smartphone and, well, I carry my phone everywhere.

It’s interesting, therefore, to see Warren Ellis' newsletter shoutout being responded to by Marc Weidenbaum. It seems they both have dedicated ‘music’ screens on their smartphones. Personally, I use an Android launcher that makes that impracticle. Also, I tend to switch between only four apps: Spotify (I’ve been a paid subscriber for 13 years now), Auxio (for MP3s), BBC Sounds (for radio/podcasts), and AntennaPod (for other podcasts). I don’t use ‘widgets’ other than the player in the notifications bar, if that counts.

Are we in a post-album era for music?

One of the downsides of getting older is that things you took to be sacred all of a sudden seem to be obsolete. For example, music albums, which have always been a part of my life, seem to now be referred to in the past tense?

There’s a whole Wikipedia article on the ‘album era’ so… it must be true.

The album era was a period in English-language popular music from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s in which the album was the dominant form of recorded music expression and consumption. It was primarily driven by three successive music recording formats: the 33⅓ rpm long-playing record (LP), the audiocassette, and the compact disc. Rock musicians from the US and the UK were often at the forefront of the era, which is sometimes called the album-rock era in reference to their sphere of influence and activity. The term "album era" is also used to refer to the marketing and aesthetic period surrounding a recording artist's album release.Source: Album era | Wikipedia

Upgrading an iPod Video for use in 2022

I’m an OG when it comes to MP3 players, having owned an Archos MP3 Jukebox while I was at uni in about 2001. It was ridiculously expensive for me as a student, but I was working at HMV at the time, and I was (and still am!) really into music.

In the end, I ‘upgraded’ the battery in it and managed to melt the entire thing, then switched to Spotify for all of my music in 2009. But there’s definitely part of me that wants to get back to what I would consider ‘real’ music listening.

While I do have plenty of MP3s and FLAC files on my smartphone, there’s just something about having a separate device for music. And you don’t get more iconic than an iPod. So this project is super-cool and once again has me thinking…

See also: How To Enjoy Your Own Digital Music

See also: ListenBrainz

I realised something not so long ago - I was being very lazy. I'd often just play my weekly/daily mix, or some playlist I made up a long time ago. I'd never really think about what music I liked + what music I wanted to listen to. I think this is in part due to the fact that almost any music was available - which made choosing even more difficult.Source: Building an iPod for 2022 | Ellie.wtfAnyway. Over the weekend I took apart a 5.5th gen iPod Classic (or iPod Video) and made it suit 2022 a little better :D

The album is no longer the unit of musical currency

I’m sitting listening to the new Kings of Convenience album while writing this. As this article points out, listening to albums is an increasingly unlikely thing to in the era of streaming music services.

This isn’t accidental: it’s easy to hop between services when the unit of currency is an ‘album’. But when it’s a regularly-updated playlist that’s only available on a particular platform (e.g. Spotify) that’s a different proposition altogether.

To help listeners find their way in the endless aisles of digital music, streaming providers created playlists — but this new way of listening has created unintended consequences for artists and songwriters. Today, three services make up two-thirds of the streaming economy: Spotify, which has an estimated 32 percent of the market, Apple Music (18 percent), and Amazon Music (14 percent). But Spotify dominates the conversation both because of its market power and its immensely popular playlists. In 2017, 68 percent of all listening on Spotify was from a company or user playlist, according to the company’s 2018 Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Its platform has more than 4 billion playlists, 3,000 of which are owned by Spotify, curated by a mix of algorithms and editors.Source: How streaming made hit songs more important than the pop stars who sing them | VoxIts most prominent playlists have serious cultural power. RapCaviar shapes the sound of hip-hop, and can turn indie rappers into household names. The genre-agnostic, slightly quirky playlist Lorem curates the vibe for Spotify’s Gen Z listeners. In 2020, listeners ages 16 to 40 used playlists as their primary source for discovering new music on the platform, according to the company. So today, a placement atop one of its playlists can make or break a song.

Spotify isn’t shy about the marketing power of its playlists. In its SEC filing, the company wrote as much, crediting Lorde’s breakout global success to her placement on a single playlist: Sean Parker’s Hipster International. But her example may be an outlier. The challenge for most artists is that playlist listeners frequently don’t know who they’re listening to. A song with high completion rates on a playlist might end up on more playlists, accumulating millions of streams for an artist who remains effectively nameless. In the best-case scenario, these streams, which pay very low royalties compared to radio, could help land the song a coveted advertisement, or better yet, pique the attention of Top 40 radio programmers.

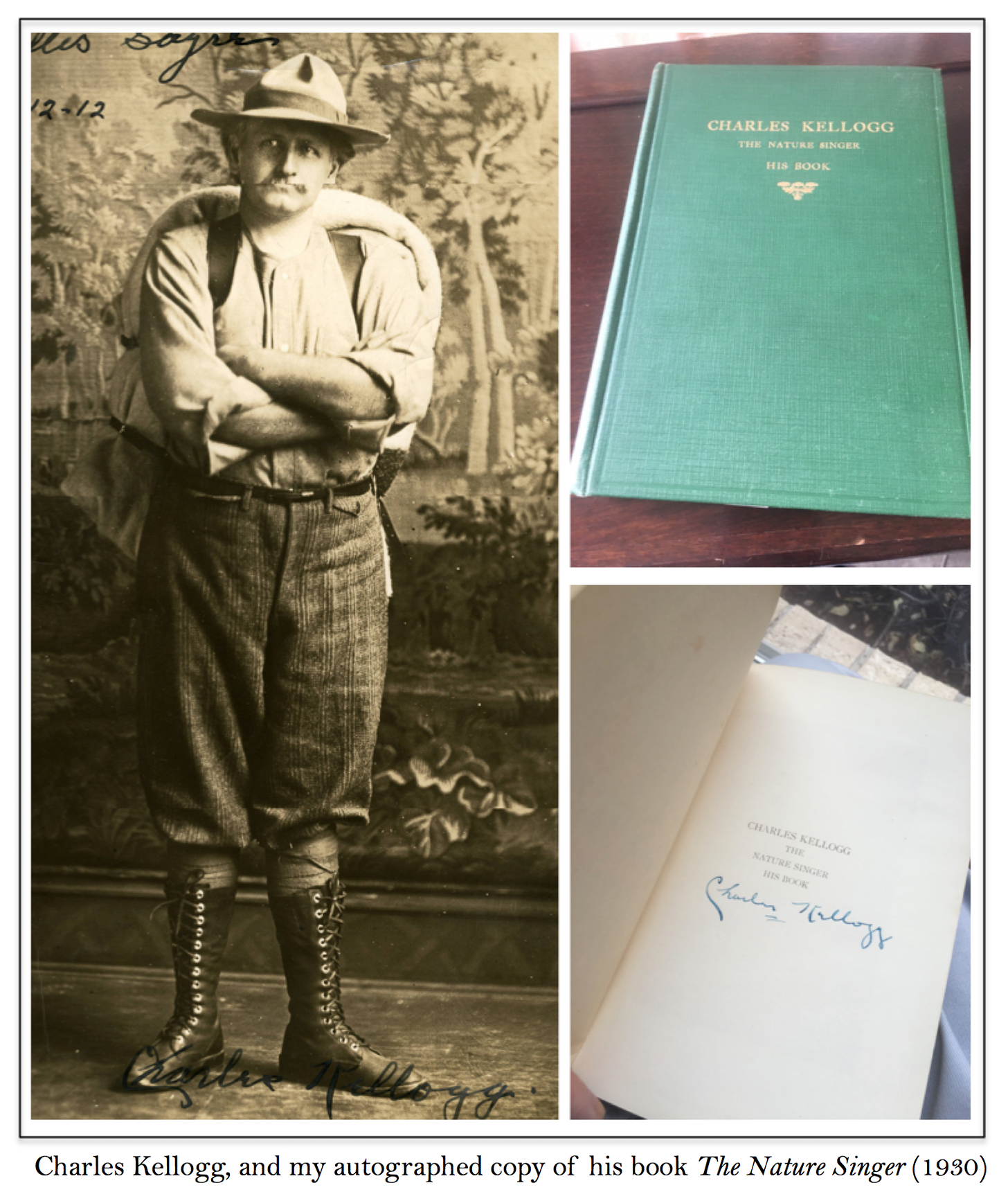

People pay selective attention to what they deem important

I really enjoyed this article, ostensibly about the amazing vocal technique of one Charles Kellogg who could “put out fire by singing”. Apparently he could also imitate birdsong perfectly. There’s an interesting video at the end of the article about that.

More interesting to me, however, is the anecdote about what Kellogg’s ear was attuned to, even in a busy urban environment.

Perhaps the most revealing anecdote tells of him walking down the street during a visit to New York, when Kellogg stopped short at the intersection of Broadway and West 34th Street. He turned to his companion and said: “Listen, I hear a cricket.” His friend responded: “Impossible—with all this racket you couldn’t hear a tiny sound like that.” And it was true: cars, trolleys, passersby, shouting newspaper vendors created such a hustle and bustle that no cricket could possibly be discerned in the hubbub.Source: The Man Who Put Out Fires with Music | Culture Notes of an Honest BrokerBut, true to his word, Kellogg scrutinized their busy surroundings, and a moment later crossed the street with his companion following along—and there on a window ledge pointed to a tiny cricket. “What astonishing hearing you have,” his friend marveled. But instead of responding, Kellogg reached into his pocket and pulled out a dime, which he dropped on the sidewalk. The moment the coin hit the pavement it made a small pinging noise, and everybody within 50 feet of the sound stopped and started looking for the coin. People listen for what’s most important for them, he later explained: for New Yorkers it’s the sound of money, for Charles Kellogg it was the chirping of a cricket.

Like the flight of a sparrow through a lighted hall, from darkness into darkness

⚽ Is it too late to halt football’s final descent into a dystopian digital circus?

🎧 Why Music is Helpful for Concentration

😬 I Lived Through Collapse. America Is Already There.

😷 COVID-19 map for schools (UK)

Quotation-as-title from St Bede. Image from top-linked post.

The truth is too simple: one must always get there by a complicated route

😍 Drone Awards 2020: the world seen from above

😷 Adequate Vitamin D Levels Cuts Risk Of Dying From Covid-19 In Half, Study Finds

🔊 The BBC is releasing over 16,000 sound effects for free download

👍 Proposal would give EU power to boot tech giants out of European market

🎧 The Hidden Costs of Streaming Music

Quotation-as-title by George Sand. Image from top-linked post.

To be happy, we must not be too concerned with others

🧠 Your Brain Is On the Brink of Chaos

😫 ‘Ugh fields’, or why you can’t even bear to think about that task

👍 The Craft of Teaching Confidence

🏝️ Log on, chill out: holiday resorts lure remote workers to fill gap left by tourists

🎧 Producer 9th Wonder on Producing Beats for Kendrick Lamar

Quotation-as-title by Albert Camus. Image from top-linked article.

Friday fertilisations

I've read so much stuff over the past couple of months that it's been a real job whittling down these links. In the end I gave up and shared a few more than usual!

Image via Kottke.org

That which we do not bring to consciousness appears in our lives as fate

Today's title is quotation from Carl Jung, via a recent issue of New Philosopher magazine. I thought it was a useful frame for a discussion around a few things I've been reading recently, including an untranslatable Finnish word, music and teen internet culture, as well as whether life does indeed get better once you turn forty.

Let's start with that Finnish word, discussed in Quartzy by Olivia Goldhill:

At some point in life, all of us get that unexpected call on a Tuesday afternoon that distorts our world and makes everything else irrelevant: There’s been an accident. Or, you need surgery. Or, come home now, he’s dying. We get through that time, somehow, drawing on energy reserves we never knew we had and persevering, despite the exhaustion. There’s no word in English for the specific strength it takes to pull through, but there is a word in Finnish: sisu.

Olivia Goldhill

I'm guessing Goldhill is American, as we English have a term for that: Blitz spirit. It's even been invoked as a way of getting us through the vagaries of Brexit! 🙄

Despite my flippancy, there are, of course, words that are pretty untranslatable between languages. But one thing that unites us no matter what language we speak is music. Interestingly, Alexis Petridis in The Guardian notes that there's teenage musicians making music in their bedrooms that really resonates across language barriers:

For want of a better name, you might call it underground bedroom pop, an alternate musical universe that feels like a manifestation of a generation gap: big with teenagers – particularly girls – and invisible to anyone over the age of 20, because it exists largely in an online world that tweens and teens find easy to navigate, but anyone older finds baffling or risible. It doesn’t need Radio 1 or what is left of the music press to become popular because it exists in a self-contained community of YouTube videos and influencers; some bedroom pop artists found their music spread thanks to its use in the background of makeup tutorials or “aesthetic” videos, the latter a phenomenon whereby vloggers post atmospheric videos of, well, aesthetically pleasing things.

Alexis Petridis

Some people find this scary. I find it completely awesome, but may be over-compensating now that I've passed 35 years of age. Who wants to listen to and like the same music as everyone else?

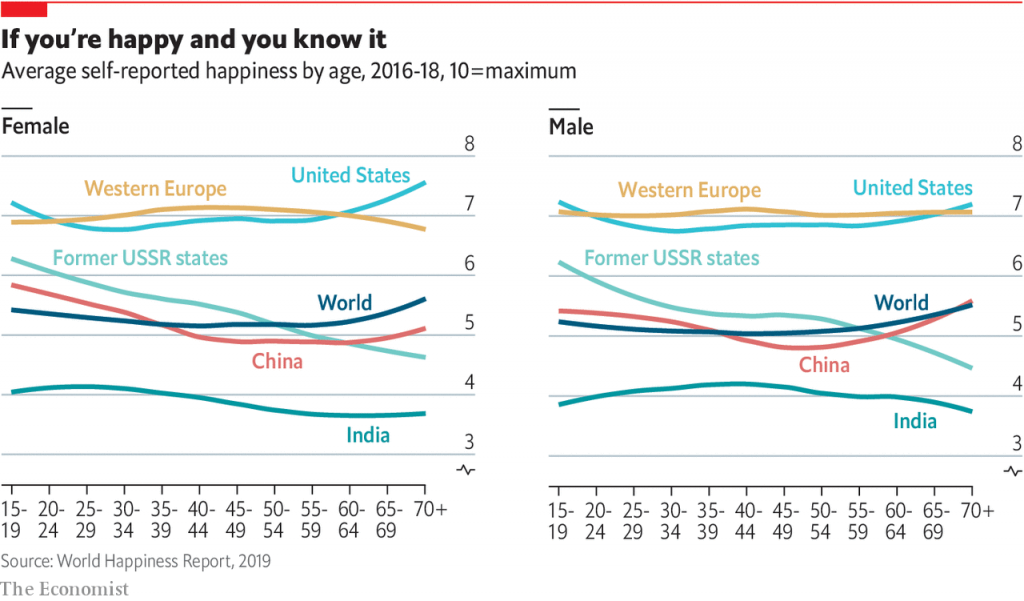

Talking of getting older, there's a saying that "life begins at forty". Well, an article in The Economist would suggest that, on average, the happiness of males in Western Europe doesn't vary that much.

I'd love to know what causes that decline in the former USSR states, and the uptick in the United States? The article isn't particularly forthcoming, which is a shame.

Perhaps as you get to middle-age there's a realisation that this is pretty much going to be it for the rest of your life. In some places, if you have the respect of your family, friends, and culture, and are reasonably well-off, that's no bad thing. In other cultures, that might be a sobering thought.

One of the great things about studying Philosophy since my teenage years is that I feel very prepared for getting old. Perhaps that's what's needed here? More philosophical thinking and training? I don't think it would go amiss.

Also check out:

Creating media, not just consuming it

My wife and I are fans of Common Sense Media, and often use their film and TV reviews when deciding what to watch as a family. In their newsletter, they had a link to an article about strategies to help kids create media, rather than just consume it:

Kids actually love to express themselves, but sometimes they feel like they don't have much of a voice. Encouraging your kid to be more of a maker might just be a matter of pointing to someone or something they admire and giving them the technology to make their vision come alive. No matter your kids' ages and interests, there's a method and medium to encourage creativity.They link to apps for younger and older children, and break things down by what kind of kids you've got. It's a cliché, but nevertheless true, that every child is different. My son, for example, has just given up playing the piano, but loves making electronic music:

Most kids love music right out of the womb, so transferring that love into creation isn't hard when they're little. Banging on pots and pans is a good place to start -- but they can take that experience with them using apps that let them play around with sound. Little kids can start to learn about instruments and how sounds fit together into music. Whether they're budding musicians or just appreciators, older kids can use tools to compose, stay motivated, and practice regularly. And when tweens and teens want to start laying down some tracks, they can record, edit, and share their stuff.The post is chock-full of links, so there's something for everyone. I'm delighted to be able to pair it with a recent image Amy shared in our Slack channel which lists the rules she has for her teenage daughter around screentime. I'd like to frame it for our house!

Source: Common Sense Media

Image: Amy Burvall (you can hire her)