Piracy and the art of cultural archiving

Shortly before Daft Punk’s album Discovery was released, I managed to download a version of it which must have been exfiltrated from the studio. It was subtly different to the version that was released and, to be honest, I preferred it. Sadly, I’ve long since lost the MP3s, and the chance of me finding anything other than the official version these days is minimal.

This article is about the preservation of music, movies, and books. What copyright maximalists don’t realise is that piracy is actually amazing at ensuring that cultural diversity flourishes and is preserved. It’s definitely worth a read.

(It’s also interesting to me how this intersects what I posted earlier about AI-generated music and fandom, because both intersect with ‘official’ narratives and our current understanding of copyright.)

"Your local bookseller cannot creep into your home in the middle of the night and reclaim the contents of your bookshelf," the legal scholars Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz observe in their 2016 book The End of Ownership. "But Amazon exercises a very different kind of practical power over your digital library. Your Kindle runs software written by Amazon, and it features a persistent network connection. That means Amazon can send it instructions—to delete a book or even replace it with a new version—without any intervention from you." The potential for mischief was clear as early as 2009, when someone started selling bootleg Kindle editions of George Orwell's 1984 and Amazon reacted by dispatching even some purchased copies to the memory hole.Source: Online Outlaws Preserve the History of Music, Movies, and Books | ReasonThe fearful mood intensifies whenever politics enters the picture. When books by Agatha Christie, Roald Dahl, and other long-dead authors were reedited to reflect what are said to be “contemporary sensitivities,” many e-books were automatically updated even for readers who had bought them long before. During the George Floyd protests of 2020, several streaming services, unable to stop the abusive policing that set off the unrest, decided instead to edit or eliminate TV episodes where characters appeared in blackface. (This wasn’t an anti-racist gesture so much as a cargo-cult copy of an anti-racist gesture—an elaborate imitation built without figuring out the functions of the component parts—and so it mostly affected shows that had presented blackface with obvious disapproval.) Several songs with words that might offend listeners have gone missing from Spotify or (as with Lizzo’s “Grrrls,” which originally included the term spaz) were replaced with new versions.

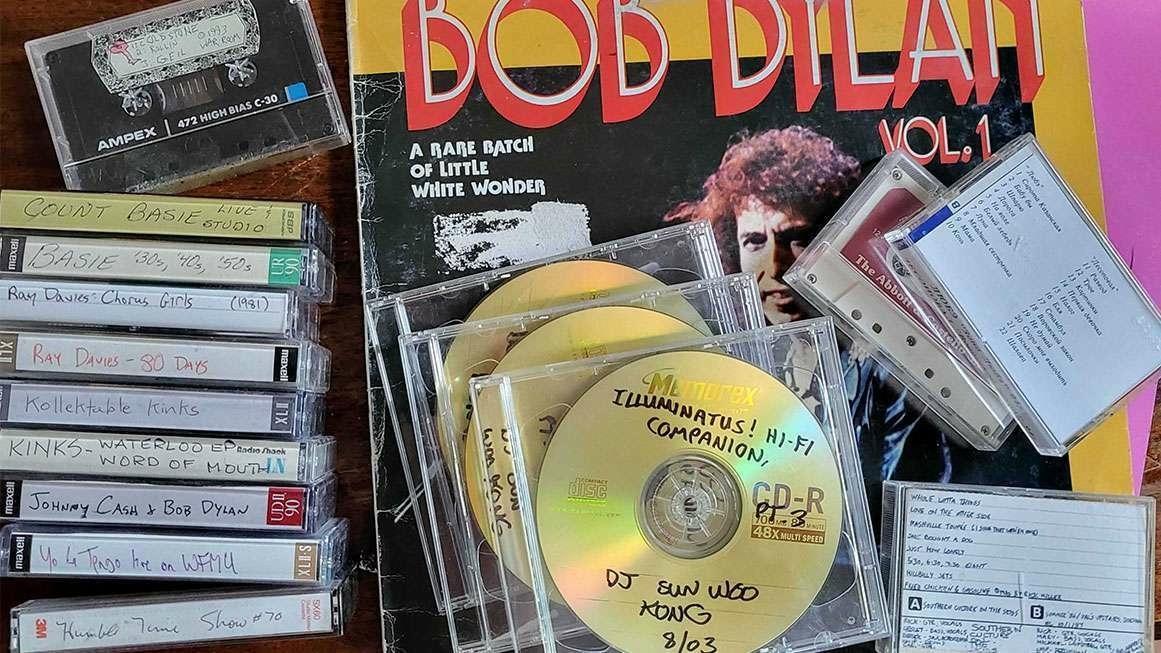

Every time news breaks of one of these deletions, a refrain echoes online: Buy physical media! The internet is too impermanent, the argument goes: The real cultural cornucopia was in the outside world.

As is often the case with nostalgia, this leaves out a lot. We still have access to far more media than we did in the days before the mass internet. Yes, this includes that politically controversial material: It takes less than a minute to dig up the unredacted version of “Grrrls” on YouTube (just search for lizzo grrrls spaz), and it’s not hard to find material that was withdrawn from circulation long before the internet era. (I’m told the ’90s were a less politically correct time than today, but back then you needed to track down a bootleg DVD or videotape if you were curious about Song of the South. Now it’s posted on the Internet Archive.) It’s too easy to take the internet’s riches for granted and to forget how much was inaccessible just a few decades ago.

But while we shouldn’t want to return to those pre-web days, there’s something to be said for that online-offline hybrid space where my old tape-trading network dwelled—if not as a world to recreate, then as a way to think about cultural preservation. And there’s something to be said for the bootleggers and pirates. Whether or not they mean to do it, they’re salvaging pieces of our heritage.