- Build in 'Spaces' (for client projects, etc.)

- Split screen view

- Easel (clip *live* parts of web pages)

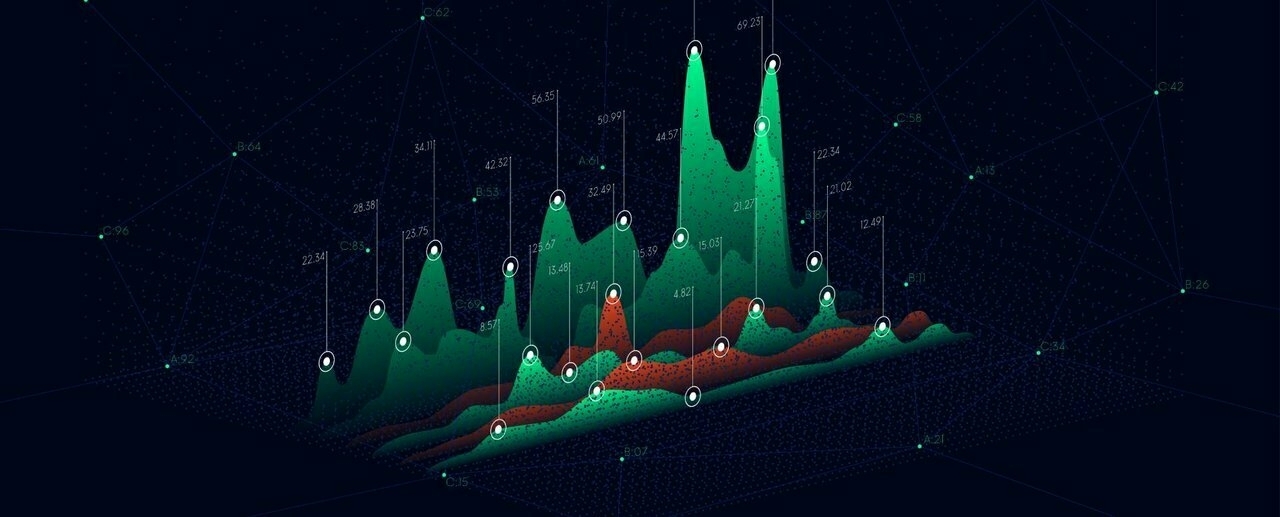

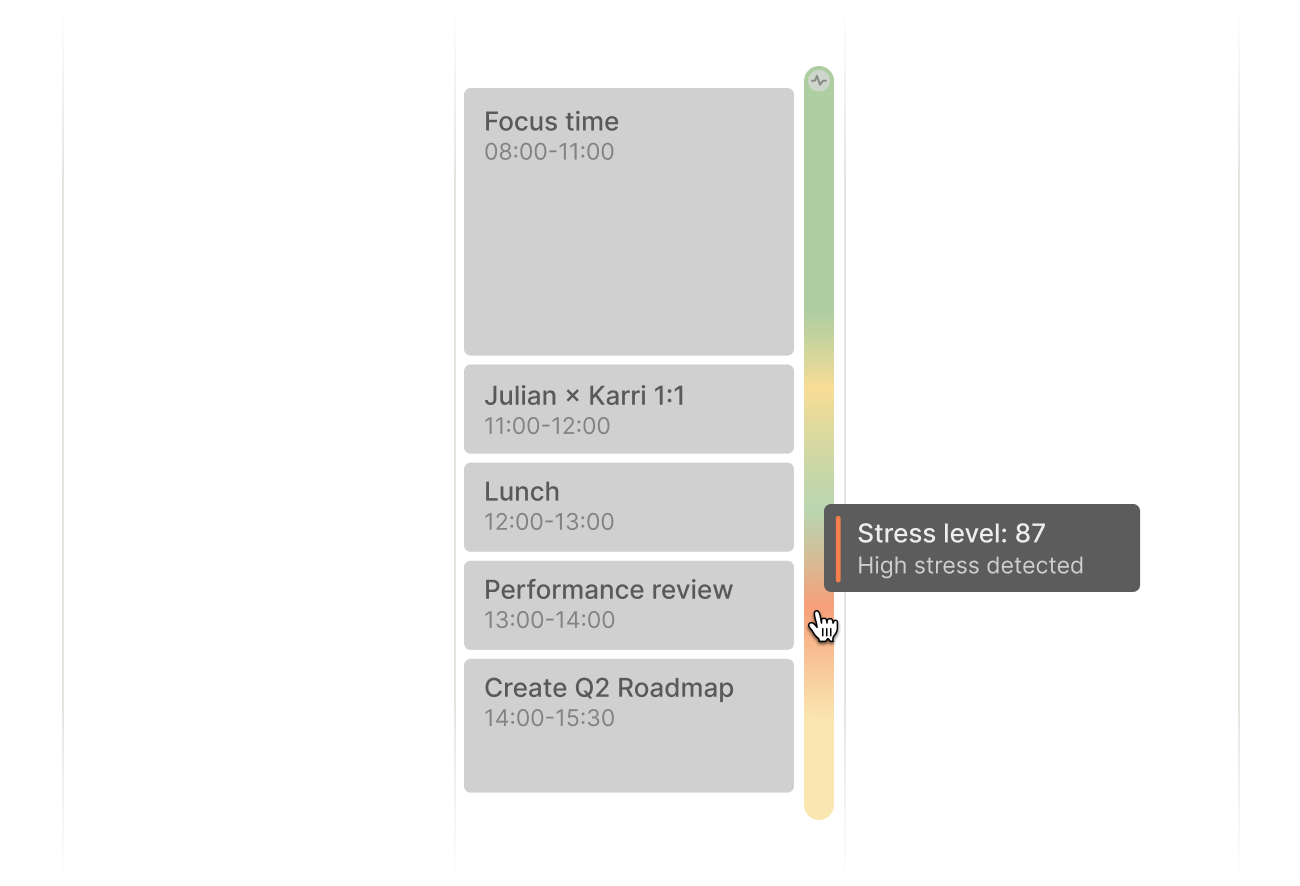

Calendars as data layers

I run my life by Google Calendar, so I found this post about different data layers including both past and future data points really interesting.

As someone who also pays attention to their stress level as reported by a Garmin smartwatch, and as someone who suffers from migraines, this kind of data would be juxtaposition would be super-interesting to me.

Our digital calendars turned out to be just marginally better than their pen and paper predecessors. And since their release, neither Outlook nor Google Calendar have really changed in any meaningful way.Source: Multi-layered calendars | julian.digital[…]

Flights, for example, should be native calendar objects with their own unique attributes to highlight key moments such as boarding times or possible delays.

This gets us to an interesting question: If our calendars were able to support other types of calendar activities, what else could we map onto them?

[…]

Something I never really noticed before is that we only use our calendars to look forward in time, never to reflect on things that happened in the past. That feels like a missed opportunity.

[…]

My biggest gripe with almost all quantified self tools is that they are input-only devices. They are able to collect data, but unable to return any meaningful output. My Garmin watch can tell my current level of stress based on my heart-rate variability, but not what has caused that stress or how I can prevent it in the future. It lacks context.

Once I view the data alongside other events, however, things start to make more sense. Adding workouts or meditation sessions, for example, would give me even more context to understand (and manage) stress.

[…]

Once you start to see the calendar as a time machine that covers more than just future plans, you’ll realize that almost any activity could live in your calendar. As long as it has a time dimension, it can be visualized as a native calendar layer.

Your personal time management strategy sucks

Too many pointless TLAs (Three Letter Acronyms) in this blog post, but it’s redeemed by having a core message that human beings are not cogs in a machine and have a finite time to accomplish their goals.

Although there have been plenty of people I’ve come across in my career who are always “super busy” there’s one person in my orbit in particular at the moment who seems to carry the world on their shoulders. As this post points out, this is due to an inability to focus on what’s important.

(The diagram below exudes peak 1990s management consultancy vibes, so I’m only including it for comedy value.)

People inform me they are busy as if it is a badge of honor. For me, it is a signal that they have a weak personal Playing to Win strategy.Source: Being ‘Too Busy’ Means Your Personal Strategy Sucks | Roger Martin[…]

[T]o have an effective personal strategy, you need to be deliberative about choosing where to deploy your limited available hours in tasks that your particular set of capabilities enable you to generate a win by creating disproportionate value for your organization. And, since this doesn’t happen automatically, you need a personal management system for doing it on an ongoing basis — because on this front, eternal vigilance is the price of effectiveness.

[…]

Remember that strategy is what you do not what you say. So, even if you don’t think of yourself as having a personal Playing to Win strategy, step back and reverse engineer what it actually is based on what you actually do.

Saying "I don't know" is a privilege

Paul Graham is a smart guy. He’s a venture capitalist, and here he’s in conversation with Tyler Cowen, an economist. Both men are further to the right, politically, than me — so I winced a little at their references to the ‘far left’.

That being said, it’s an interesting episode and Cowen’s rapid-fire questioning is a useful tactic for getting guests to be more candid than they would otherwise be. What I found fascinating about Graham’s responses was that he would often say “I don’t know” instead of the prosaic “that’s a great question”. I guess once you’ve got the standing he has, there’s no need for him to pretend otherwise.

Source: Paul Graham on Ambition, Art, and Evaluating Talent (Ep. 186) | Conversations with TylerTyler and Y Combinator co-founder Paul Graham sat down at his home in the English countryside to discuss what areas of talent judgment his co-founder and wife Jessica Livingston is better at, whether young founders have gotten rarer, whether he still takes a dim view of solo founders, how to 2x ambition in the developed world, on the minute past which a Y Combinator interviewer is unlikely to change their mind, what YC learned after rejecting companies, how he got over his fear of flying, Florentine history, why almost all good artists are underrated, what’s gone wrong in art, why new homes and neighborhoods are ugly, why he wants to visit the Dark Ages, why he’s optimistic about Britain and San Fransisco, the challenges of regulating AI, whether we’re underinvesting in high-cost interruption activities, walking, soundproofing, fame, and more.

Actions speak louder than words

This article popped up on my feeds a couple of weeks ago and I recognised the organisation behind the website. Having listened to an excellent Art of Manliness podcast episode featuring Dr John Barry, I knew that ‘The Centre for Male Psychology’ is actually legit.

What this article discusses I’ve found true in my own life. I am by temperament introspective, which means for many years I thought the answer to any form of melancholy came in thinking. But, actually, I’ve found the answer to be in action in doing things such as climbing mountains, running, and doing things with my hands.

The two ways of regulating emotions have implications for the field of mental health, which relies predominately on talking therapy – in particular talking about feelings. Does this not suggest that there could be, and perhaps needs to be, more emphasis on discussing the therapeutic value of action? It may not be practical to conduct therapy while engaged in physical activity such as a gym workout or while out walking in the streets, but the therapeutic discussion can at least focus more on the “doing” aspects of a man’s life. For example a therapist might ask how did problem XYZ make a man act out, along with exploring which physical activities or responses might help him to modulate such emotions more optimally in future. Does riding a Jet Ski, or going for a jog, or building some wooden furniture make him feel better or worse? Does that difficult manoeuvre in the video game remind of difficulties in his relationship with his girlfriend? Does the same video game provide some optimism that if he can get past the difficult manoeuvre within the game then perhaps he can find a way around the impasse with his girlfriend? Activities like these provide a symbolic canvas on which men project, and then work through various scenarios of real life, with potential to shift affective resonances in the process.Source: Men tend to regulate their emotions through actions rather than words | The Centre for Male PsychologyWhen a man talks about how he operated a lathe, did some welding, restored a bit of discarded and broken furniture, might he be sharing a strategy of how he successfully redirected suicidal feelings? Perhaps we should not be so quick to shut down these conversations with accusations of being work obsessed, effectively stymieing natural male expressions with injunctions to talk less about activities and to communicate more effusively with feelings words. For many men, activities are the preferred canvases on which they can process feelings and carve out some genuine psychological equilibrium.

This is probably a reason why men talk so much about work, sports, building things, computer games, recreational activities – it may be their preferred way of communicating the ways they wrestle with psychological issues. Sadly, the therapeutic industry is quick to chastise men’s preference for intelligent actions, conflating them with pathological reflexes such as unconscious acts of aggression, dependence on drugs and booze, and other destructive versions of so-called “acting-out” as they are so often branded.

Marginally Employed

For various reasons I will explain elsewhere this post by Dan Sinker, which I read this morning, was particularly important to my life. Dan is awesome, and am thankful for his candor.

A month or so ago I was at a cookout for an old work colleague and friend. It was 100% people who I haven't seen since at least the pandemic hit, and most of them a few years even before that. And so, obviously, the first question anyone would ask is "what are you up to now," and, well, that's sort of a hard question for me to answer. As has been established on this blog before, I do a lot of things. Some of them are job-shaped, while others look, well, like an entire fictional town in Ohio. All of them are important to me and all of them are a little hard to explain.Source: Best Laid Plans | dansinker.comAnd so it was on that night that my brain—sometimes a friend, other times an enemy—responded “Well, I’m marginally employed,” before launching into a full-throated explanation of the wild world of Question Mark, Ohio to increasingly concerned onlookers.

I left the cookout feeling pretty weird, if I’m being honest. Since I’d last seen most of the folks that were there, they’d moved on to really incredible work. And here I was cobbling together bits and pieces of job-shaped things while spinning a yarn about a town plagued with disappearances. And then there was the term I used: marginally employed, which felt right but also felt a little embarrassing.

And then something happened. I talked about this on Says Who afterward and I heard from a bunch of folks who said, basically: Hey, me too. And I realized like, wait a second: I want to be doing work like I’m doing. Work that’s weird and exciting and, admittedly, hard to describe to people while also gnawing on some ribs. I don’t want to be doing a 9-5. I want to be marginally employed.

And so I made a patch. It’s really simple, just maroon on white and set in Cooper Black, my very favorite typeface. It reads, simply, “Marginally Employed.” No apologies, no frills. I love it. You might too. It’s $10 and ships free in the US.

Meredith Whittaker on AI doomerism

This interview with Signal CEO Meredith Whittaker in Slate is so awesome. She brings the AI 'doomer' narrative back time and again both to surveillance capitalism, and the massive mismatch between marginalised people currently having harm done to them and the potential harm done to very powerful people.

Source: A.I. Doom Narratives Are Hiding What We Should Be Most Afraid Of | SlateWhat we’re calling machine learning or artificial intelligence is basically statistical systems that make predictions based on large amounts of data. So in the case of the companies we’re talking about, we’re talking about data that was gathered through surveillance, or some variant of the surveillance business model, that is then used to train these systems, that are then being claimed to be intelligent, or capable of making significant decisions that shape our lives and opportunities—even though this data is often very flimsy.

[...]

We are in a world where private corporations have unfathomably complex and detailed dossiers about billions and billions of people, and increasingly provide the infrastructures for our social and economic institutions. Whether that is providing so-called A.I. models that are outsourcing decision-making or providing cloud support that is ultimately placing incredibly sensitive information, again, in the hands of a handful of corporations that are centralizing these functions with very little transparency and almost no accountability. That is not an inevitable situation: We know who the actors are, we know where they live. We have some sense of what interventions could be healthy for moving toward something that is more supportive of the public good.

[...]

My concern with some of the arguments that are so-called existential, the most existential, is that they are implicitly arguing that we need to wait until the people who are most privileged now, who are not threatened currently, are in fact threatened before we consider a risk big enough to care about. Right now, low-wage workers, people who are historically marginalized, Black people, women, disabled people, people in countries that are on the cusp of climate catastrophe—many, many folks are at risk. Their existence is threatened or otherwise shaped and harmed by the deployment of these systems.... So my concern is that if we wait for an existential threat that also includes the most privileged person in the entire world, we are implicitly saying—maybe not out loud, but the structure of that argument is—that the threats to people who are minoritized and harmed now don’t matter until they matter for that most privileged person in the world. That’s another way of sitting on our hands while these harms play out. That is my core concern with the focus on the long-term, instead of the focus on the short-term.

Playing the right game

Thanks to Laura for pointing me towards this post by Simone Stolzoff. There’s so much to unpack, which perhaps I’ll do in a separate post. It touches on reputation and credentialing, but also motivation, gamification, and “value self-determination”.

Extracting yourself from the false gods of vanity metrics is hard, but massively liberating. It starts with realising small things like you don’t actually need to keep up a ‘streak’ on Duolingo to learn a language. But there’s a through line from that to coming to the conclusion that you don’t need to win awards for your work, or the status symbol of a fancy car/house.

I interviewed over 100 workers—from kayak guides in Alaska to Wall Street bankers in Manhattan—and met several people who achieved nearly every goal set out for them, only to realize they were winning a game they didn’t enjoy playing.Source: Playing a Career Game You Actually Want to Win | EveryHow do so many of us find ourselves in this position, climbing ladders we don’t truly want to be on? C. Thi Nguyen, a philosopher and game design researcher at the University of Utah, has some answers. Nguyen coined the term “value capture,” a phenomenon that I came to see all around me after I learned about it. Here’s how it works.

Most games establish a world with a clear goal and rankable achievements: Pac-Man must eat all the dots; Mario must save the princess. Video games offer what Nguyen calls “a seductive level of value clarity.” Get points, defeat the boss, win. In many ways, video games are the only true meritocratic games people can play. Everyone plays within clearly defined boundaries, with the same set of inputs. The most skilled wins.

Our careers are different. The games we play with our working hours also come with their own values and metrics that matter. Success is measured by how much money you make—for your company and for yourself. Promotions, bonuses, and raises mark the path to success, like dots along the Pac-Man maze.

These metrics are seductive because of their simplicity. “You might have a nuanced personal definition of success,” Nguyen told me, “but once someone presents you with these simple quantified representations of a value—especially ones that are shared across a company—that clarity trumps your subtler values.” In other words, it is easier to adopt the values of the game than to determine your own. That’s value capture.

There are countless examples of value capture in daily life. You get a Fitbit because you want to improve your health but become obsessed with maximizing your steps. You become a professor in order to inspire students but become fixated on how often your research is cited. You join Twitter because you want to connect with others but become preoccupied by the virality of your content. Naturally, maximizing your steps or citations or retweets is good for the platforms on which these status games are played.

Bad work

Not just artists - we all go through life’s ups and downs, good periods and bad. Right now is the least tolerant time since I’ve been alive. Everyone’s supposed to be on it 24/7.

Viewed in the context of the episode, Sylvester is talking, specifically, about the “professionalization” and “commercialization” of art, and basically the hype machine of the art world.Source: Artists must be allowed to make bad work | Austin Kleon

Digital wallets for verifiable credentials

Purdue University had something like this almost a decade ago, but there’s even more call for this kind of thing now, post-pandemic and in a Verifiable Credentials landscape.

Everyone’s addicted to marrying ‘skills’ with ‘jobs’ but I think there’s definitely an Open Recognition aspect to all of this.

ASU Pocket captures students’ traditional and non-traditional educational credentials, which are now, with the emergence of verifiable credentials, more portable than ever before. This gives students the autonomy to securely own, control and share their holistic evidence of learning with employers.Source: ASU Pocket: A digital wallet to capture learners’ real-time achievementsA digital wallet, like ASU Pocket, holds verifiable credentials – which are digital representations of real-world credentials like government-issued IDs, passports, driver’s licenses, birth certificates, educational degrees, professional certifications, awards, and so on. In the past, these credentials have been stored in physical form, making them susceptible to fraud and loss. However, with advances in technology, these credentials can be stored electronically, using cryptographic techniques to ensure their authenticity. This makes it possible to verify the credential without revealing sensitive information, such as a social security number.

[…]

At ASU Pocket, we also view verifiable credentials as an important tool for social impact. They provide a way for people to document their skills and accomplishments, which can be used to gain new opportunities. For example, someone with a verifiable skill credential for customer service might be able to use it to get a job in a call center. Likewise, someone with a verifiable credential for computer programming might be able to use it to get a job as a software developer.

In both cases, the verifiable credential provides a way for the individual to demonstrate their skills and qualifications gained through or outside of traditional learning pathways. This is especially impactful for marginalized groups who may have difficulty obtaining traditional credentials, such as degrees or certifications.

AI generated art aesthetic

Yes, it’s “just typing prompts” but then drawing is “just making marks on paper”. Love this aesthetic.

Source: An Improbable Future

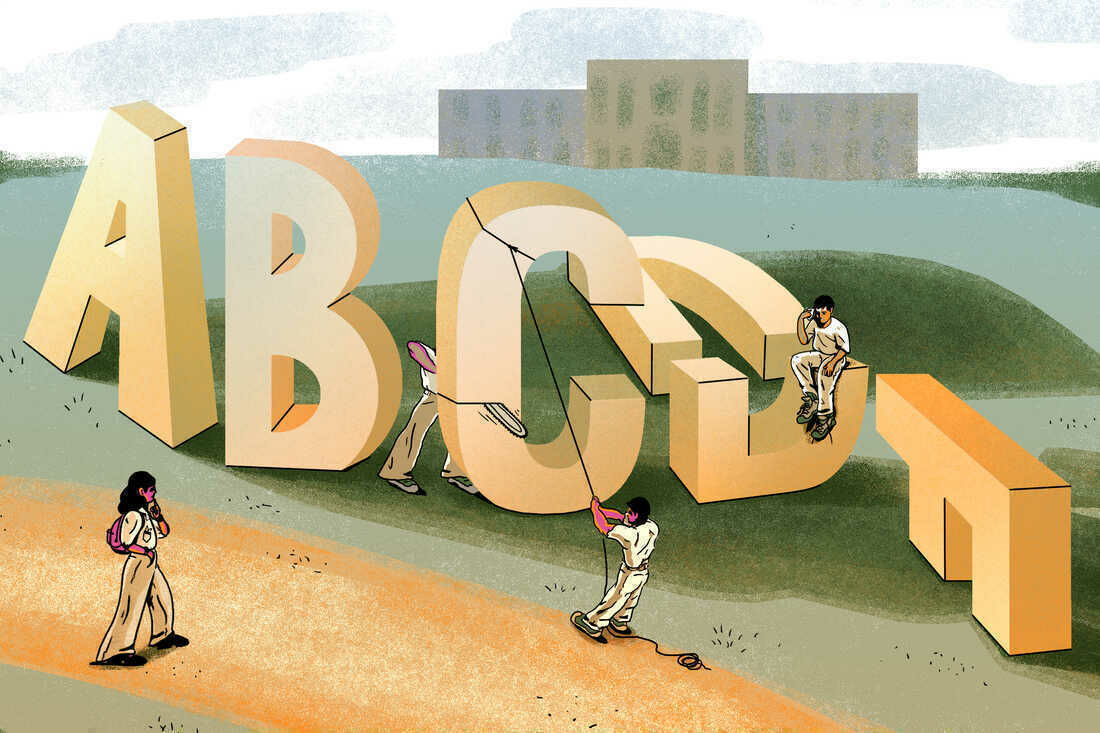

Ungrading the university experience

There’s some discussion of students ‘gaming the system’ in this article about ungrading university courses, but nothing much about AI tools like ChatGPT. This movement has been gathering pace for years, and I think that we’re at a tipping point.

Hopefully, this will lead to more Open Recognition practices rather than just breaking down chunky credentials into microcredentials.

[A]dvocates say the most important reason to adopt un-grading is that students have become so preoccupied with grades, they aren't actually learning.Source: Some colleges are eliminating freshman grades by ‘ungrading’ | NPR“Grades are not a representation of student learning, as hard as it is for us to break the mindset that if the student got an A it means they learned,” said Jody Greene, special adviser to the provost for educational equity and academic success at UCSC, where several faculty are experimenting with various forms of un-grading.

If a student already knew the material before taking the class and got that A, “they didn’t learn anything,” said Greene. And “if the student came in and struggled to get a C-plus, they may have learned a lot.”

[…]

[S]everal colleges and universities… already practice unconventional forms of grading. At Reed College in Oregon, students aren’t shown their grades so that they can “focus on learning, not on grades,” the college says. Students at New College of Florida complete contracts establishing their goals, then get written evaluations about how they’re doing. And students at Brown University in Rhode Island have a choice among written evaluations that only they see, results of “satisfactory” or “no credit,” and letter grades — A, B or C, but no D or F.

MIT has what it calls “ramp-up grading” for first-year students. In their first semesters, they get only a “pass,” without a letter; if they don’t pass, no grade is recorded at all. In their second semesters, they get letter grades, but grades of D and F are not recorded on their transcripts.

Reducing website carbon emissions by blocking ads

Blocking advertising on the web is not only good for increasing the speed and privacy of your own web browsing, but also good for the planet.

What is the environmental impact of visiting the homepage of a media site? What part do advertising, and analytics, play when it comes to the carbon footprint? We tried to answer these questions using GreenFrame, a solution we developed to measure the footprint of our own developments.Source: Media Websites: 70% of the Carbon Footprint Caused by Ads and Stats | MarmelabThe results are insightful: up to 70% of the electricity consumption (and therefore carbon emissions) caused by visiting a French media site is triggered by advertisements and stats. Therefore, using an ad blocker even becomes an ecological gesture.

[…]

Overall we observe the same thing: the carbon footprint of a website decreases if there are no ads or trackers on the website. The difference is significant: Between 32% and 70% of the energy consumed by the browser and the network is due to monetization.

The websites analyzed generate between 70 and 130 million visits per month, and their work has therefore a real impact on the environment.

Reducing the consumption of one of these sites by only 10% (20mWh), per visit for a site with 100 million monthly visitors is equivalent to saving 24,000 kWh per year.

Switching to Arc

It’s not often I’ll post tools here, but after a few days of using it, I’m sold on the Arc browser.

My web browser history over the last quarter of a century goes something like: Netscape Navigator –> Internet Explorer –> Firefox –> Chrome –> Brave –> Arc.

Perhaps I should record a screencast, but the three things I like most about Arc are:

Experience a calmer, more personal internet in this browser designed for you. Let go of the clicks, the clutter, the distractions.Source: Arc | The Browser Company

The sleight of hand of crypto

Cory Doctorow is doing the rounds for his new book at the moment. But because he’s Cory, he’s not just phoning it in, or parroting the same lines.

Take this interview in Jacobin, for example. Yes, he’s talking about why he decided to write a story about crypto, but he’s so well informed about this stuff on a technical level that it’s a joy to read the way he explains things.

There’s this kind of performative complexity in a lot of the wickedness in our world — things are made complex so they’ll be hard to understand. The pretense is they’re hard to understand because they’re intrinsically complex. And there’s a term in the finance sector for this, which is “MEGO:” My Eyes Glaze Over. It’s a trick.Source: Cory Doctorow Explains Why Big Tech Is Making the Internet Terrible | Jacobin[…]

A lot of the crypto stuff starts with what a sleight-of-hand artist would do. “Alright, we know that cryptography works and can keep secrets and we know that money is just an agreement among people to treat something as valuable. What if we could use that secrecy when processing payments and in so doing prevent governments from interrupting payments?”

After this setup, the con artist can get the mark to pick his or her poison: “It will stop big government from interfering with the free market” or “It will stop US hegemony from interdicting individuals who are hostile to American interests in other countries and allow them to make transactions” or “It will let you send money to dissident whistleblowers who are being blocked by Visa and American Express.” These are all applications that, depending on the mark’s political views, will affirm the rightness of the endeavor. The mark will think, that is a totally legitimate application.

It starts with a sleight of hand because all the premises that the mark is agreeing with are actually only sort of right. It’s a first approximation of right and there are a lot of devils in the details. And understanding those details requires a pretty sophisticated technical understanding.

AI writing, thinking, and human laziness

In a Twitter thread by Paul Graham that I came across via Hacker News he discusses how it’s always safe to bet on human laziness. Ergo, most writing will be AI-generated in a year’s time.

However, as he says, to write is to think. So while it’s important to learn how to use AI tools, it’s also important to learn how to write.

In this post by Alan Levine, he complains about ChatGPT’s inability to write good code. But the most interesting paragraph (cited below) is the last one in which we, consciously or unconsciously, put the machine on the pedestal and try and cajole it into doing something we can already do.

I’m reading Humanly Possible by Sarah Bakewell at the moment, so I feel like all of this links to humanism in some way. But I’ll save those thoughts until later and I’ve finished the book.

ChatGPT is not lying or really hallucinating, it is just statistically wrong.Source: Lying, Hallucinating? I, MuddGPT | CogDogBlogAnd the thing I am worried about is that in this process, knowing I was likely getting wrong results, I clung to hope it would work. I also found myself skipping my own reasoning and thinking, in the rush to refine my prompts.

Taxing land rather than labour

I think I’ve always been somewhat of a Georgist, but perhaps didn’t know the name for it. The central tenet is that governments should be funded by a tax on land rather than labour.

There’s also the idea that this tax would replace all other taxes, which I guess is kind of the mirror of Universal Basic Income replacing all other benefits. I’m happy to be convinced on that, but already sold on the land tax idea.

Georgism, in some sense, is the idea that no one really owns land, but instead, you rent its exclusive use from everyone else through Land Value Taxes.Source: Developing an intuition for Georgism | Atoms vs Bits[…]

If I claimed to own a 1-dimensional line that ran on the ground, and that you need to step over it, or that I owned a 6-inch cube floating off the ground, and you needed to duck under it, you’d rightly think I was insane.

However, if I own a plot of land, i.e. a 2D space on the surface of the earth, it’s considered either insane (or tragically primitive) to not believe in this.

(Yes, through air rights you own 3D space, but it generally has to be above 2D land, floating cubes still seem nonsensical).

Image: Gautier Pfeiffer

AI and work socialisation

I've bolded what I consider to be the most important part of this article by danah boyd. It's a reflection on two different 'camps' when it comes to AI and jobs, but she surfaces an important change that's already happened in society when it comes to the workforce: we just don't train people any more.

Couple this with AI potentially replacing lower-paid jobs (where people might 'learn the ropes while working) and... well, it's going to be interesting.

Source: Deskilling on the Job | danah boydWhile getting into what it means to be human is likely to be a topic of a later blog post, I want to take a moment to think about the future of work. Camp Automation sees the sky as falling. Camp Augmentation is more focused on how things will just change. If we take Camp Augmentation’s stance, the next question is: what changes should we interrogate more deeply? The first instinct is to focus on how changes can lead to an increase in inequality. This is indeed the most important kinds of analysis to be done. But I want to noodle around for a moment with a different issue: deskilling.

[...]

Today, you are expected to come to most jobs with skills because employers don’t see the point of training you on the job. This helps explain a lot of places where we have serious gaps in talent and opportunity. No one can imagine a nurse trained on the job. But sadly, we don’t even build many structures to create software engineers on the job.

However, there are plenty of places where you are socialized into a profession through menial labor. Consider the legal profession. The work that young lawyers do is junk labor. It is dreadfully boring and doesn’t require a law degree. Moreover, a lot of it is automate-able in ways that would reduce the need for young lawyers. But what does it do to the legal field to not have that training? What do new training pipelines look like? We may be fine with deskilling junior lawyers now, but how do we generate future legal professionals who do the work that machines can’t do?

This is also a challenge in education. Congratulations, students: you now have tools at your disposal that can help you cut corners in new ways (or outright cheat). But what if we deskill young people through technology? How do we help them make the leap into professions that require more advanced skills?

[...]

Whether you are in Camp Augmentation or Camp Automation, it’s really important to look holistically about how skills and jobs fit into society. Even if you dream of automating away all of the jobs, consider what happens on the other side. How do you ensure a future with highly skilled people? This is a lesson that too many war-torn countries have learned the hard way. I’m not worried about the coming dawn of the Terminator, but I am worried that we will use AI to wage war on our own labor forces in pursuit of efficiency. As with all wars, it’s the unintended consequences that will matter most. Who is thinking about the ripple effects of those choices?