- Envisage an afterlife (in other words, a belief that some form of existence continues beyond death).

- Believe that an afterlife occurs in some sort of ‘underworld’, located beneath (rather than on or above) the world of the living. That implies that they may have developed some very embryonic sense of cosmology.

- Conceive the idea of physically burying their dead - in that ‘underworld’.

- Give grave goods to dead members of their community - an apparent act that implies that they may have believed that the dead would somehow be able to use them in an afterlife.

- Carry out potential rituals - specifically funerary meals - inside their ‘underworld’.

- Create rudimentary art (abstract designs) around the entrance to at least one of the burial chambers in that ‘underworld’.

- Plan some sort of relatively complex lighting system (either a succession of small fires and/or torches) to enable them to penetrate their ‘underworld’ and take their dead there.

Would you survive in medieval Europe?

Realistically, I’m never going to watch an hour-long YouTube video which is mainly a talking head. I mean, I’m into history, but I’m not that into it.

Thankfully, Open Culture has summarised some of the most important points. If you’re the kind of person who watches a lot of YouTube, then maybe you want to add this to your queue?

In the new video above, history Youtuber Premodernist provides an hour’s worth of advice to the modern preparing to travel back in time to medieval Europe — beginning with the declaration that “you will very likely get sick.”Source: Advice for Time Traveling to Medieval Europe: How to Staying Healthy & Safe, and Avoiding Charges of Witchcraft | Open CultureThe gastrointestinal distress posed by the “native biome” of medieval European food and drink is one thing; the threat of robbery or worse by its roving packs of outlaws is quite another. “Crime is rampant” where you’re going, so “carry a dagger” and “learn how to use it.” In societies of the Middle Ages, people could only protect themselves by being “enmeshed in social webs with each other. No one was an individual.” And so, as a traveler, you must — to put it in Dungeons-and-Dragons terms — belong to some legible class. Though you’ll have no choice but to present yourself as having come from a distant land, you can feel free to pick one of two guises that will suit your obvious foreignness: “you’re either a merchant or a pilgrim.”

Image: DALL-E 3

More like Grammarly than Hal 9000

I’m currently studying towards an MSc in Systems Thinking and earlier this week created a GPT to help me. I fed in all of the course materials, being careful to check the box saying that OpenAI couldn’t use it to improve their models.

It’s not perfect, but it’s really useful. Given the extra context, ChatGPT can not only help me understand key concepts on the course, but help relate them more closely to the overall context.

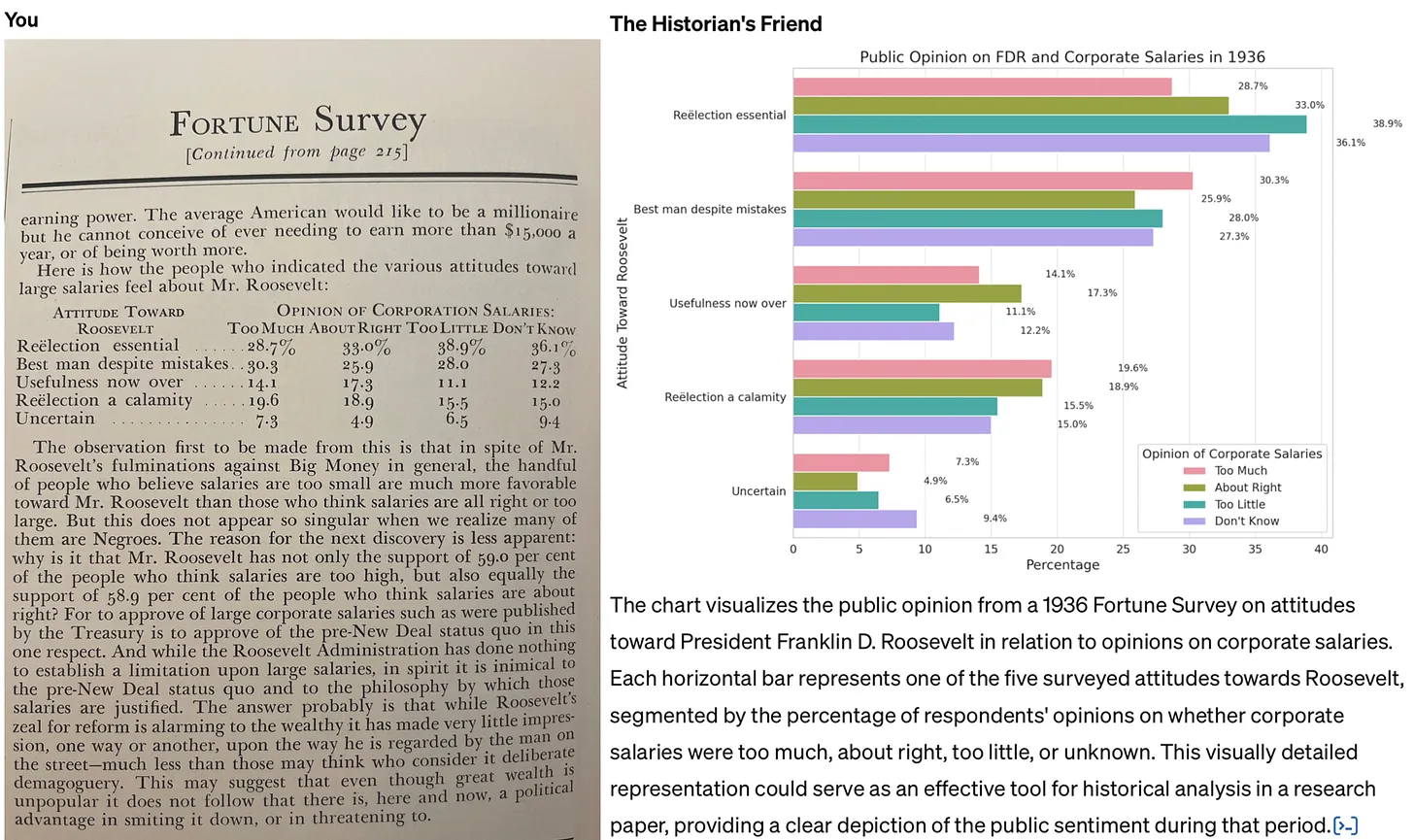

This example would have been really useful on the MA in Modern History I studied for 20 years ago. Back then, I was in the archives with primary sources such as minutes from the meetings of Victorians discussing educational policy, and reading reports. Being able to have an LLM do everything from explain things in more detail, to guess illegible words, to (as below) creating charts from data would have been super useful.

The key thing is to avoid following the path of least resistance when it comes to thinking about generative AI. I’m referring to the tendency to see it primarily as a tool used to cheat (whether by students generating essays for their classes, or professionals automating their grading, research, or writing). Not only is this use case of AI unethical: the work just isn’t very good. In a recent post to his Substack, John Warner experimented with creating a custom GPT that was asked to emulate his columns for the Chicago Tribune. He reached the same conclusion.Source: How to use generative AI for historical research | Res Obscura[…]

The job of historians and other professional researchers and writers, it seems to me, is not to assume the worst, but to work to demonstrate clear pathways for more constructive uses of these tools. For this reason, it’s also important to be clear about the limitations of AI — and to understand that these limits are, in many cases, actually a good thing, because they allow us to adapt to the coming changes incrementally. Warner faults his custom model for outputting a version of his newspaper column filled with cliché and schmaltz. But he never tests whether a custom GPT with more limited aspirations could help writers avoid such pitfalls in their own writing. This is change more on the level of Grammarly than Hal 9000.

In other words: we shouldn’t fault the AI for being unable to write in a way that imitates us perfectly. That’s a good thing! Instead, it can give us critiques, suggest alternative ideas, and help us with research assistant-like tasks. Again, it’s about augmenting, not replacing.

Our ancestors were using complex tools and woodworking approaches almost half a million years ago

Nature reports that, at the Kalambo Falls archaeological site in Zambia, researchers have unearthed the earliest known examples of woodworking — dating back at least 476,000 years. This is a significant find as it includes two logs interlocked by a hand-cut notch, a method previously unseen in early human history. The discovery also features four other wood tools: a wedge, digging stick, cut log, and a notched branch. These artifacts demonstrate early humans' advanced skills in shaping wood for various purposes, challenging the traditional view that early hominins primarily used stone tools.

I’ve also never heard of the approach that the team used: luminescence dating. This is a method that helps determine when the wood was last exposed to light, and various wood analysis techniques.

The findings, especially the interlocked logs, suggest that early humans had the capability to construct large structures and manipulate wood in complex ways. It’s a groundbreaking discovery, as it not only pushes back the timeline of woodworking in Africa but also sheds new light on the cognitive abilities and technological diversity of our early ancestors. Amazing.

The Quaternary sequence is a 9-m-deep exposure above the Kalambo River (BLB1 is a geological section). Sediments are fluvial sands and gravels with occasional, discontinuous beds of fine sands, silts and clays with wood preserved in the lowermost 2 m.... A permanently elevated water table has preserved wood and plant remains (Supplementary Information Section 1). The depositional sequence is typical of a high- to moderate-energy sandbed river that underwent lateral migration. The sands are dominated by a lower unit of horizontal bedding and an upper unit of planar/trough cross-bedding. Upper and lower sand units are separated by fine sands, silts and clays with plant material deposited in still water after the river migrated/avulsed elsewhere in the floodplain. Wood is deposited in this environment either through anthropogenic emplacement, or naturally transported in the flow, and snagged on sand bedforms.Source: Evidence for the earliest structural use of wood at least 476,000 years ago | Nature[…]

Sixteen samples for dating were collected at Site BLB by hammering opaque plastic tubes into the sediment. A combination of field gamma spectrometry, laboratory alpha and beta counting and geochemical analyses were used to determine radionuclide content, and the dose rate and age calculator42 was used to calculate radiation dose rate. Sand-sized grains (approximately 150 to 250 µm in diameter) of quartz and potassium-rich feldspar were isolated under red-light conditions for luminescence measurements and measured on Risø TL/OSL instruments using single-aliquot regenerative dose protocols. Single-grain quartz OSL measurements dated sediments younger than around 60 kyr, but beyond this age the OSL signal was saturated. pIR IRSL measurements of aliquots consisting of around 50 grains of potassium-rich feldspars were able to provide ages for all samples collected. The pIR IRSL signal yielded an average value for anomalous fading of 1.46 ± 0.50% per decade. Where quartz OSL and feldspar pIR IRSL were applied to the same samples, the ages were consistent within uncertainties without needing to correct for anomalous fading. The conservative approach taken here has been to use ages without any correction for fading. If a fading correction had been applied then the ages for the wooden artefacts would be older.

Soul houses and false doors

Egyptology is endlessly fascinating to me. I only got to scratch the surface teaching a course called Medicine Through Time as a History teacher fifteen years ago, but it’s something I’ll perhaps return to in my retirement.

I’m not sure which time period you’d like to go and have a look at (not live in, that’s a different thing entirely) but for me it’s Ancient Egypt. It all seems so other-worldly.

The Ancient Egyptians world they inhabited with innumerable otherworldly entities: invisible, yet with immense power. Demons haunted the desert wastes and goddesses dwelled in the marshes of the Nile Delta, but the spirits of the dead were omnipresent. Ancestor worship was an important part of household religion and the belief that the dead could not only be communicated with, but could also use their power to both help and hurt living beings, was an ingrained part of the ancient Egyptian belief system.Source: In Ancient Egypt, Soul Houses and False Doors Connected the Living and the Dead | Atlas Obscura[…]

False doors were a specific type of funerary decoration often found in the tombs of the Egyptian elite during the Old Kingdom, the period more than 4,000 years ago when the Giza pyramids were built. False doors were carved from a single piece of limestone and took the form of a narrow doorway surrounded by inscribed door jambs and surmounted by a lintel. The tomb’s occupant was usually represented seated at a table laden with food offerings: vegetables, fruits, bread, wine, beer, and meats—everything a soul would need to sustain itself in the afterlife. The family members and friends of the deceased could also be immortalized on the false door. These carvings were not portraits, however, but idealized representations. Both men and women were shown in the prime of their life: strong, healthy, vigorous, and fertile.

[…]

False doors were generally the preserve of the extreme elite, those state officials who could afford to hire artists and craftspeople to build their multichambered stone tombs. The vast majority of the population of Egypt had no such resources. But they too required a way to magically pass offerings from the living world to sustain the souls of their ancestors in the afterlife.

In place of stone, they turned to the muddy clay of the Nile, of which there was an abundance. Carefully, they crafted and fired small models of houses complete with courtyards. They filled the courtyards with models of bread and vegetables, grain bins and pots filled with beer. Then they placed these objects, collectively known as soul houses, on top of the graves of their family and friends. The soul houses became imbued with magic and through them, food offerings could pass between the worlds of the living and the worlds of the dead. They are simple objects, but they show that the ordinary ancient Egyptians were every bit as concerned as the social elites with providing for their ancestors in the afterlife.

Stonehenge had nothing to do with druids

I’ve only ever driven past Stonehenge, as it’s a long way from where I grew up, and by the time I was old enough to go independently there were all sorts of restrictions around it.

It’s been interesting over my lifetime to see how the understanding of its significance has changed, especially as other henges and monuments have been found nearby.

Seventeenth-century English antiquarians thought that Stonehenge was built by Celtic Druids. They were relying on the earliest written history they had: Julius Caesar’s narrative of his two unsuccessful invasions of Britain in 54 and 55 BC. Caesar had said the local priests were called Druids. John Aubrey (1626–1697) and William Stukeley (1687–1765) cemented the Stonehenge/Druid connection, while self-styled bard Edward Williams (1747–1826), who changed his name to Iolo Morganwg, invented “authentic” Druidic rituals.Source: Stonehenge Before the Druids (Long, Long, Before The Druids) | JSTOR Daily[…]

“The false association of [Stonehenge] with the Druids has persisted to the present day,” [historian Carole M.] Cusak writes, “and has become a form of folklore or folk-memory that has enabled modern Druids to obtain access and a degree of respect in their interactions with Stonehenge and other megalithic sites.”

Meanwhile, archaeologists continue to explore the centuries of construction at Stonehenge and related sites like Durrington Walls and the Avenue that connects Stonehenge to the River Avon. Neolithic Britons seem to have come together to transform Stonehenge into the ring of giant stones—some from 180 miles away—we know today. Questions about construction and chronology continue, but current archeological thinking is dominated by findings and analyses of the Stonehenge Riverside Project of 2004–2009. The Stonehenge Riverside Project’s surveys and excavations made up the first major archeological explorations of Stonehenge and surroundings since the 1980s. The project archaeologists postulate that Stonehenge was a long-term cemetery for cremated remains, with Durrington Walls serving as the residencies and feasting center for its builders.

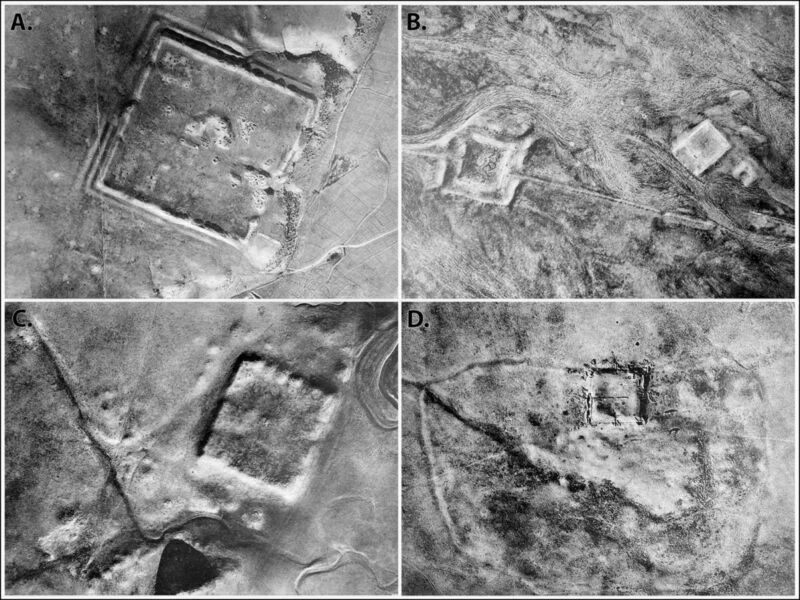

The French Jesuit priest who surveyed Roman forts by air

I’m not sure what’s more fascinating: the scale of the Roman army’s building (in this case, in Syria) or the French Jesuit priest who surveyed them by aeroplane.

Either way, the history geek in me loves this.

Back in the early days of aerial archaeology, a French Jesuit priest named Antoine Poidebard flew a biplane over the northern Fertile Crescent to conduct one of the first aerial surveys. He documented 116 ancient Roman forts spanning what is now western Syria to northwestern Iraq and concluded that they were constructed to secure the borders of the Roman Empire in that region.Source: I spy with my Cold War satellite eye… nearly 400 Roman forts in the Middle East | Ars TechnicaNow, anthropologists from Dartmouth have analyzed declassified spy satellite imagery dating from the Cold War, identifying 396 Roman forts, according to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity. And they have come to a different conclusion about the site distribution: the forts were constructed along trade routes to ensure the safe passage of people and goods.

[…]

The Dartmouth team analyzed CORONA and HEXAGON images covering some 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 square miles) in the northern Fertile Crescent, mapping 4,500 known archaeological sites and other features that seemed to be sites of interest. Some 10,000 previously undiscovered sites were added to their database. Poidebard’s forts have their own category in that database, based on their distinctive square shape and size, and the Dartmouth researchers found many more likely forts lurking in the spy satellite imagery.

The results confirmed Poidebard’s 1934 finding of a line of forts running along the strata Dioceltiana and also revealed several new forts along that route. But the survey also showed many new, previously undetected Roman forts running west-southwest between the Euphrates Valley and western Syria, as well as connecting the Tigris and Khabur rivers. That seems more suggestive of the forts supporting the movement of troops, supplies, or trade goods across the Fertile Crescent—cultural exchange sites rather than barriers. The authors date most of the forts to between the second and sixth centuries CE, after which there was widespread abandonment of the sites, although a few remained occupied into the medieval period.

Sycamore Stump

There is, or rather was, a tree that symbolised the North East of England. Standing at a dip in the ground along Hadrian’s Wall called ‘Sycamore Gap’, it’s a tree I’ve visited many times with friends and family. Last year, when I walked the wall in 72 hours, it was a familiar touchstone.

Now the iconic 200 year-old tree, which featured in the film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, is gone. Felled by a 16 year-old in an act of wanton vandalism. On a World Heritage Site. Some people just want to watch the world burn.

It didn’t take long for someone to rename the place on Google Maps where the tree used to stand to ‘Sycamore Stump’. Hopefully they will build some kind of memorial to it. I do think it’s difficult for someone not from the region to understand just how important things like this are to one’s identity.

A 16-year-old boy has been arrested in northern England in connection with what authorities described as the “deliberate” felling of a famous tree that had stood for nearly 200 years next to the Roman landmark Hadrian’s Wall.Source: ‘Incredibly sad day’: Teen arrested in England after felling ancient tree | Al Jazeera[…]

Photographs from the scene on Thursday showed the tree was cut down near the base of its trunk, with the rest of it lying on its side.

Northumbria Police said the teen was arrested on suspicion of causing criminal damage. He was in police custody and assisting officers with their inquiries.

[…]

“This is an incredibly sad day,” police Superintendent Kevin Waring said. “The tree was iconic to the North East and enjoyed by so many who live in or who have visited this region.”

Image: Oli Scarff / Agence France-Presse (taken from NYT article)

Bad historical maps

Like the author of this article, I love a good map. Whether it’s trekking across hills and mountains with an OS map, or looking through historical maps, there’s something enchanting about understanding territories.

The thing is, though, that maps are literally projections. They leave things out and therefore have to be interpreted. If the maps are out of date, or are being used in a way that’s anachronistic, that leads to a huge problem.

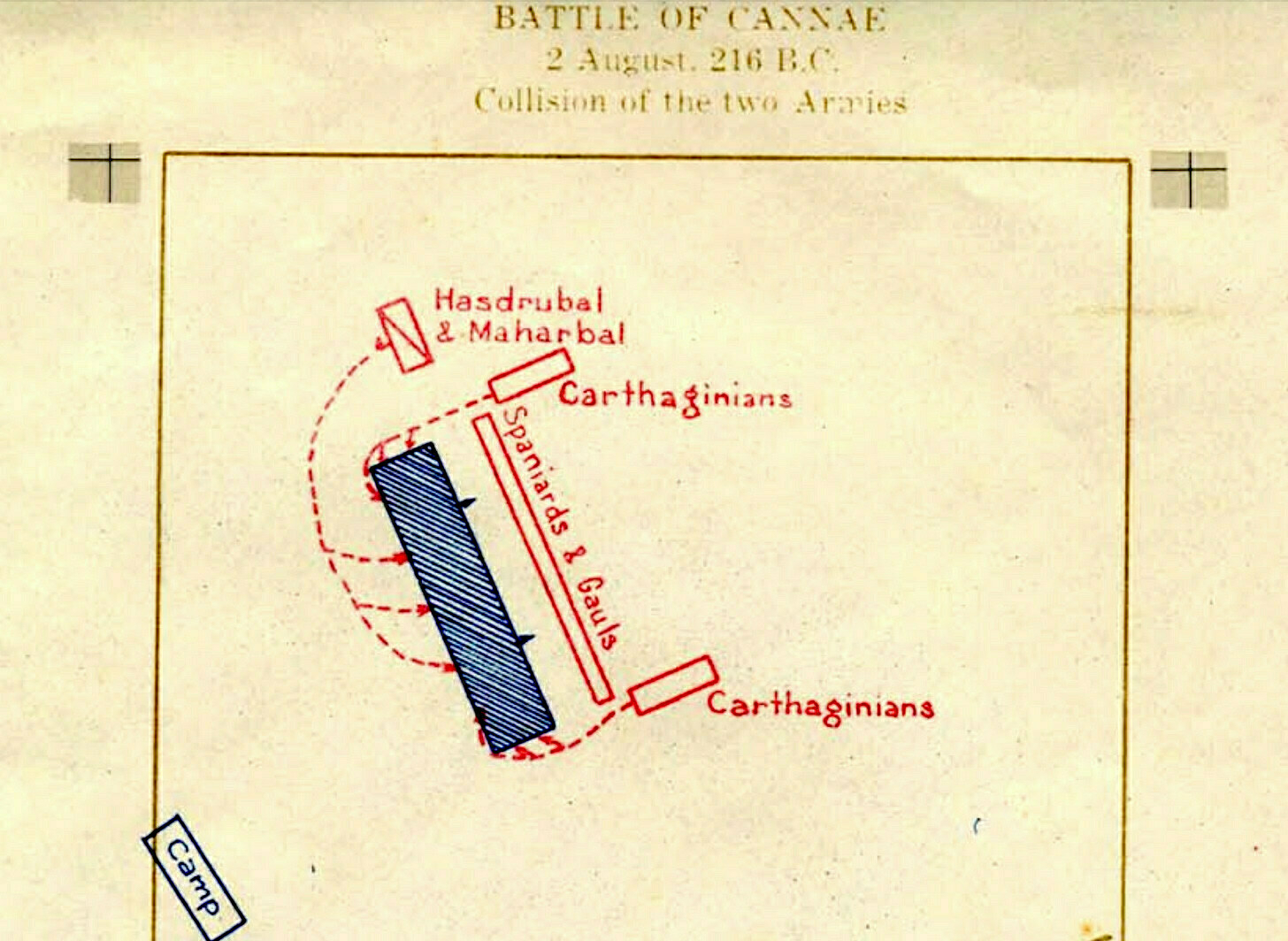

As a History teacher, I used to teach WWI but didn’t know that General von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff, was obsessed with Hannibal and the Battle of Cannae. Apparently he used stories and maps of how it played out to inform his strategy. The problem was that, not only did it happen a couple of millennia beforehand, but it probably didn’t even play out that way.

Maps like this are a big part of why I became a historian. I probably spent more time looking through the volumes of Colin McEvedy’s Penguin Atlas of History series than any other book when I was a kid.... There’s something beguiling about the thought that a simple arrangement of lines might explain the world — like seeing human history as an enormous game of Civilization 6. But of course, that’s also the problem with using maps as a way of understanding history. If you’re not careful, they go from being helpful tools to misleading simplifications.Source: Historical maps probably helped cause World War I | Res Obscura[…]

In her book The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman argues that the memory of Cannae, which was passed down through a succession of military histories until it became a virtual obsession of strategists in the 19th century, helped push the world into an unimaginable catastrophe.

It did so by offering up a model of a “battle of annihilation” that Germany’s war planners believed they could unleash on France. At the head of these planers was General von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff. The map of Cannae haunted Schlieffen’s dreams.

[…]

Cannae was no vague inspiration. It was a direct model for Germany’s invasion of Belgium and France.

[…]

As the historian Martin Samuels pointed out in his article “the Reality of Cannae,” there is no archaeological evidence for the battle. Nor are there first-hand sources of any kind. Everything we know derives from accounts written sixty years or more after Cannae itself. Suffice to say, when Samuels dug into these sources, he found as many questions as answers. The detailed maps of movements at Cannae that decorated military strategy manuals for hundreds of years, in other words, were largely fanciful. Samuels calls Cannae “the most quoted and least understood battle” in history.

The simplicity of a historical map — the clear labels, the sharp edges, and above all the reduction of thousands or millions of people into abstract symbols — is a big part of why they’re so beguiling. But it’s also why they lead us astray.

[…]

It is sometimes said that the map is not the territory. The map is not the historical argument, either.

Instead, maps are a great way to pose questions about history. They are best approached as a way in: an entry-point rather than an ending. They offer one path toward confronting the enormous complexity of “real” history — the kind made by individual people, on the decidedly imperfect and unmap-like terrain of the world.

Death, wrecks, and harsh weather

There was a time, about a decade ago, where although I was based from home, I’d be travelling pretty much every week for work. I was abroad once a month at least.

These days, perhaps with the pandemic as a catalyst, I’m slightly more wary of travelling. It’s probably also a function of age and awareness of how routines affect my body. As an historian, though, I’ve always been amazed by those people who journeyed long distances.

This post by an academic historian of medicine and the body outlines some of the dangers such travellers faced. Pretty amazing, when you think about it.

Unlike today, when it’s entirely possible to have breakfast in London, lunch in Milan and be back at home in time for supper, travel in the early modern period was no easy undertaking. More than this, it was widely acknowledged to be inherently dangerous. What, then, were the perceived risks? Even a brief survey tells us a lot about how travel was regarded in health terms.Source: The Health Risks of Travel in Early-Modern Britain | Dr Alun WitheyFirst was the risk of accident or death on the journey. In the seventeenth century even relatively short distances on horseback or in a carriage carried dangers. Falls from horses were common, causing injury or even death.

[…]

Travel by sea, even around local coasts, carried its own obvious risks of storm and wreck. So common and widely acknowledged were the vagaries of sea travel that a common reason for making a will in the early modern period was just before embarking on a voyage.

[…]

Once abroad, too travellers were at the mercy of a bevy of dangers, from unfamiliar territories and extreme landscapes to harsh weather and climate, their safety contingent on the quality of their transport and the reliability of their guides.

[…]

Even ‘foreign’ food and drink could be risky. Thomas Tryon’s Miscellania (1696) noted the dangers of ‘intemperance’ and of misjudging the effects of climate upon the body in regard to drinking alchohol [sic]

Generative AI, misinformation, and content authenticity

As a philosopher, historian, and educator by training, and a technologist by profession, this initiative really hits my sweet spot. The image below shows how, even before AI and digital technologies, altering the public record through manipulating photographs was possible.

Now, of course, spreading misinformation and disinformation is so much easier, especially on social networks. This series of posts from the Content Authenticity Initiative outlines ways in which the technology they are developing can be prove whether or not an image has been altered.

Of course, unless verification is built into social networks, this is only likely to be useful to journalists and in a court of law. After all, people tend to reshare whatever chimes with their worldview.

Although it varies in form and creation, generative AI content (a.k.a. deepfakes) refers to images, audio, or video that has been automatically synthesized by an AI-based system. Deepfakes are the latest in a long line of techniques used to manipulate reality — from Stalin's darkroom to Photoshop to classic computer-generated renderings. However, their introduction poses new opportunities and risks now that everyone has access to what was historically the purview of a small number of sophisticated organizations.Source: From the darkroom to generative AI | Content Authenticity InitiativeEven in these early days of the AI revolution, we are seeing stunning advances in generative AI. The technology can create a realistic photo from a simple text prompt, clone a person’s voice from a few minutes of an audio recording, and insert a person into a video to make them appear to be doing whatever the creator desires. We are also seeing real harms from this content in the form of non-consensual sexual imagery, small- to large-scale fraud, and disinformation campaigns.

Building on our earlier research in digital media forensics techniques, over the past few years my research group and I have turned our attention to this new breed of digital fakery. All our authentication techniques work in the absence of digital watermarks or signatures. Instead, they model the path of light through the entire image-creation process and quantify physical, geometric, and statistical regularities in images that are disrupted by the creation of a fake.

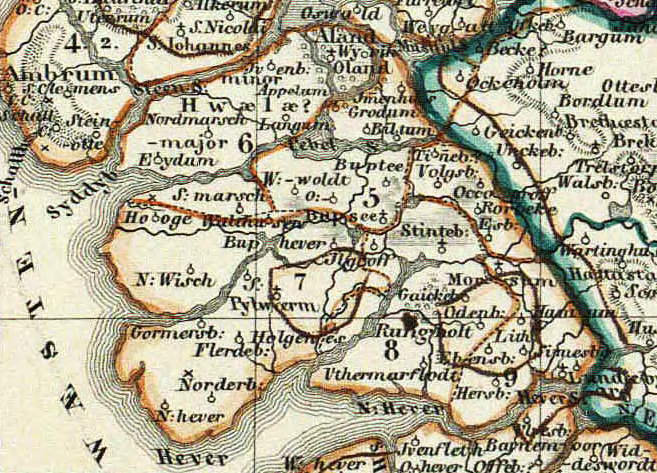

The Atlantis of the North Sea

A couple of years ago, I started subscribing to Northern Earth magazine on the recommendation of Warren Ellis. It’s quirky and brilliant.

The most recent issue contains reference to Rungholt, which I then looked up on Wikipedia. It was destroyed in the 14th century due to a storm surge. Until excavations this year people weren’t entirely sure it ever existed but it turns out it was a flourishing port town.

Rungholt was a settlement in North Frisia, in what was then the Danish Duchy of Schleswig. The area today lies in Germany. Rungholt reportedly sank beneath the waves of the North Sea when a storm tide (known as Grote Mandrenke or Den Store Manddrukning) hit the coast on 15 or 16 January 1362.Source: Rungholt | Wikipedia[…]

In June 2023, the German Research Foundation announced that researchers had found the probable location of Rungholt under mudflats in the Wadden Sea and had already mapped 10 square kilometers of the area.

[…]

Today it is widely accepted that Rungholt existed and was not just a local legend. Documents support this, although they mostly date from much later times (16th century). Archaeologists think Rungholt was an important town and port. It might have contained up to 500 houses, with about 3,000 people. Findings indicate trade in agricultural products and possibly amber. Supposed relics of the town have been found in the Wadden Sea, but shifting sediments make it hard to preserve them.

Reconstructing Tenochtitlan

This is an absolutely incredible piece of work, showing the complexity and sophistication of the Aztec empire. My favourite part is the slider that allows you to see how much of Mexico City is based upon the structure of Tenochtitlan.

The year is 1518. Mexico-Tenochtitlan, once an unassuming settlement in the middle of Lake Texcoco, now a bustling metropolis. It is the capital of an empire ruling over, and receiving tribute from, more than 5 million people. Tenochtitlan is home to 200.000 farmers, artisans, merchants, soldiers, priests and aristocrats. At this time, it is one of the largest cities in the world.Source: A Portrait of TenochtitlanToday, we call this city Ciudad de Mexico - Mexico City.

Not much is left of the old Aztec - or Mexica - capital Tenochtitlan. What did this city, raised from the lake bed by hand, look like? Using historical and archeological sources, and the expertise of many, I have tried to faithfully bring this iconic city to life.

Introducing Homo naledi

Science is awesome. I love the way that we continue to rediscover and reinterpret what it means to be human based on archaeology and scientific theories.

Using an unparalleled range of tests, experts are investigating whether a group of ‘ape-men’ succeeded in creating a complex human-like culture - potentially thousands of years before our own species, Homo sapiens, managed to do so.Source: Scientific discovery casts doubt on our understanding of human evolution | The IndependentAdding to the mystery is the fact that the now long-extinct species behaved in several key ways like modern humans - and yet appears to have been able to do that with brains which were only a third the size of ours.

The evidence assembled so far is beginning to suggest that these small-brained ‘ape-men’ may have been able to do seven remarkable things:

[...]

“We know that what we’re discovering breaks totally new ground - and is therefore likely to be controversial. That’s why we are deploying every possible type of investigative technology to ensure that the maximum amount of additional evidence can be found,” said the leader of the Rising Star Cave investigation, National Geographic and University of Witwatersrand palaeoanthropologist, Professor Lee Berger, who with co-investigator, human evolution expert Professor John Hawks, has just published a detailed National Geographic book on the discoveries, entitled Cave of Bones.

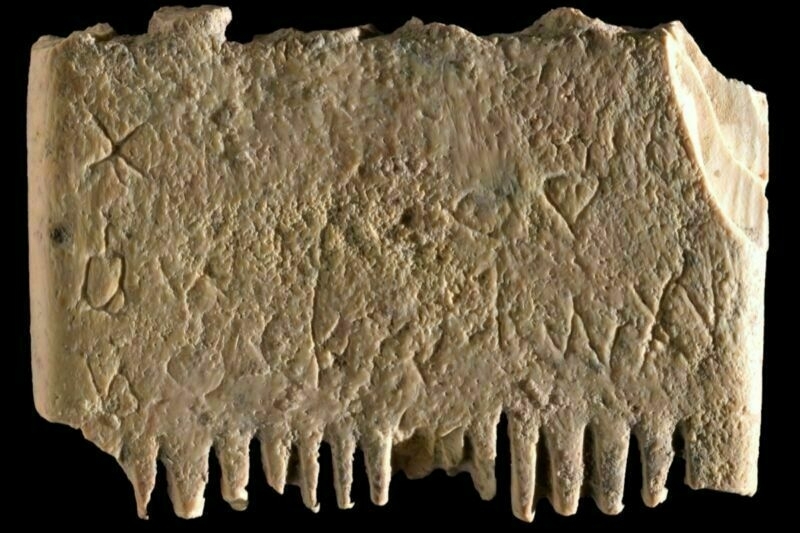

The (surprising) oldest full sentence in the Canaanite language in Israel

Apparently this comb has an inscription on it which reads “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” It was made from an imported elephant tusk!

The comb measures just 3.5 by 2.5 centimeters (roughly 1.38 by 1 inches), with teeth on both sides, although only the bases remain; the rest of the teeth were likely broken long ago. One side had thicker teeth, the better to untangle knots, while the other had 14 finer teeth, likely used to remove lice and their eggs from beards and hair. Further analysis showed noticeable erosion at the comb's center, which the authors believe was likely due to someone's fingers holding it there during use.Source: Ancient wisdom: Oldest full sentence in first alphabet is about head lice | Ars TechnicaThe authors also used X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and digital microscopy to confirm that the comb is made of ivory from an elephant tusk, suggesting it was imported. The team sent a sample from the comb to the University of Oxford’s radiometric laboratory, but the carbon was too poorly preserved to accurately date the sample.

The inscription consists of 17 letters (two damaged) that together form a complete seven-word sentence. The letters aren’t well-aligned, per the authors, nor are they uniform in size; the letters become progressively smaller and lower in the first row, with letters running from right to left. When whoever engraved the comb reached the edge, they turned it 180 degrees and engraved the second row from left to right. The engraver actually ran out of room on the second row, so the final letter is engraved just below the last letter in that row. Still, said engraver had to be fairly skilled, given the small size of the lettering.

Doomed to live in a Sisyphean purgatory between insatiable desires and limited means

I’m reading The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow. It’s an eye-opening book in many ways, and upends notions of how we see the way that people used to live.

This article suggests that 15-hour working weeks are the norm in egalitarian cultures. While working hours are steadily declining, we’re still a long way off — primarily because our desires and means are out of kilter.

New genomic and archeological data now suggest that Homo sapiens first emerged in Africa about 300,000 years ago. But it is a challenge to infer how they lived from this data alone. To reanimate the fragmented bones and broken stones that are the only evidence of how our ancestors lived, beginning in the 1960s anthropologists began to work with remnant populations of ancient foraging peoples: the closest living analogues to how our ancestors lived during the first 290,000 years of Homo sapiens’ history.Source: The 300,000-year case for the 15-hour week | Financial TimesThe most famous of these studies dealt with the Ju/’hoansi, a society descended from a continuous line of hunter-gatherers who have been living largely isolated in southern Africa since the dawn of our species. And it turned established ideas of social evolution on their head by showing that our hunter-gatherer ancestors almost certainly did not endure “nasty, brutish and short” lives. The Ju/’hoansi were revealed to be well fed, content and longer-lived than people in many agricultural societies, and by rarely having to work more than 15 hours per week had plenty of time and energy to devote to leisure.

Subsequent research produced a picture of how differently Ju/’hoansi and other small-scale forager societies organised themselves economically. It revealed, for instance, the extent to which their economy sustained societies that were at once highly individualistic and fiercely egalitarian and in which the principal redistributive mechanism was “demand sharing” — a system that gave everyone the absolute right to effectively tax anyone else of any surpluses they had. It also showed how in these societies individual attempts to either accumulate or monopolise resources or power were met with derision and ridicule.

Most importantly, though, it raised startling questions about how we organise our own economies, not least because it showed that, contrary to the assumptions about human nature that underwrite our economic institutions, foragers were neither perennially preoccupied with scarcity nor engaged in a perpetual competition for resources.

For while the problem of scarcity assumes that we are doomed to live in a Sisyphean purgatory, always working to bridge the gap between our insatiable desires and our limited means, foragers worked so little because they had few wants, which they could almost always easily satisfy. Rather than being preoccupied with scarcity, they had faith in the providence of their desert environment and in their ability to exploit this.

The Digital Dark Ages

The author of this article helps out with computer museums around the world. He talks about how its not just nostalgia which fuels them, but learning about the technological and social context in which the hardware were situated.

He then explains that future historians won’t have much of that context because of DRM, IP laws, and encryption.

To future historians—not just of computing, but of humanity—the current period will be a dark age.Source: The Digital Dark Ages | De Programmatica IpsumHow was Facebook used by students in the 2010s? We cannot show you, that version of Facebook is not hosted anywhere.

What correspondence did Vint Cerf have as president of the ACM with other luminaries of computing industry and research? We do not know; Google will not publish his emails.

What was it like playing Angry Birds on an iPhone 3G? We do not know; Apple is no longer distributing signed receipts for that binary.

What did the British cabinet discuss when they first learned of the Coronavirus pandemic? We do not know; they chatted on a private WhatsApp group.

What books were published analysing the aftermath of the Maidan coup in Ukraine? We do not know; we do not have the keys for the Digital Editions DRM. How was the coup covered in televised news? We do not know; the broadcasters used RealVideo and Windows Media Encoder and we cannot read those files.

Frozen baby woolly mammoth discovered in Yukon gold fields

Amazing. Look at how perfectly this creature was preserved in the permafrost!

I guess we’ll be seeing a lot more of this kind of thing as the permafrosts melt due to the climate crisis.

The baby woolly mammoth, named Nun cho ga, which means "big baby animal" in the Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin's Hän language, is about 140 cm long, which is a little bit longer than the other baby woolly mammoth that was found in Siberia, Russia, in May 2007.Source: ‘She’s perfect and she’s beautiful’: Frozen baby woolly mammoth discovered in Yukon gold fields | CBC NewsZazula thinks Nun cho ga was probably about 30 to 35 days old when she died. Based on the geology of the site, Zazula believes she died between 35,000 and 40,000 years ago.

“So she died during the last ice age and found in permafrost,” said Zazula.

Moonshine-enabling cow shoes

The Sunday Surfers (a name my group of friends give to ourselves when playing PlayStation) came across an abandoned moonshine still in the game Red Dead Redemption 2 last weekend. That possibly primed my brain to find this random article even more interesting than I did already!

The shoe was described in a Florida newspaper in 1922 which led to many people, including the authorities, knowing a great deal about the moonshiners’ ingenious way of preventing detection. The knowledge of the shoe didn’t immediately stop its use nor did it stop the moonshiners who just continued to think of new ways to evade police and get their product to an increasingly thirsty public.Source: Moonshiners Wore Special Shoes To Evade the Law During Prohibition

Psycho-Geography

This is incredible. I want to see it!

Each concrete slab in the Cretto di Burri measures between ten and twenty meters on each side and stands at around 1.6 meters tall. The enormous yet walkable fissures in the concrete mirror the old town’s streets and corridors, reconjuring spatial memories of the destroyed city while marking its status as uninhabitable ruins. In Burri’s imagination, the cracked landscapes of Death Valley that had served as inspiration for his work functioned as a kind of psycho-geography, suggesting the violence and trauma of fascist rule and industrialized warfare that he had experienced as an Italian citizen living through both World Wars. In similar fashion, the cracked white concrete of the Cretto di Burri memorializes and reifies the trauma and grief of the Belice earthquake, with the fissures marking not just the literal roads and streets of the original town but also the violence done to the land, people, and profoundly to the cultural memory of the site.Source: The Psycho-Geography of the Cretto di Burri | ArchDailyThe white concrete, as a common urban construction material, suggests the pale corpse of the lost city, while the textures and fissures marking the presence and memory of the old city reveal the futility of erasing and moving forward on a psycho-geographic tabula rasa. Altogether, the Cretto di Burri beautifully responds to a moment of profound cultural grief through its pared-down, yet highly suggestive form and materiality.