2023

- Poll on Mastodon (Fediverse)

- Poll on LinkedIn

- ChatGPT conversation

- Some of the most important takeaways for me were around:

- There are three main status games: dominance, virtue, and success

- Status games are hard wired into us, and we're essentially just 'status detection systems'

- Social media sites such as Twitter make it easy to signal virtue, whereas those such as Instagram make it easy to signal success.

- Trying to force people to play your type of status game is about dominance.

- Status games are why teenagers, who are new to these games, get embarrassed easily and take lots of risks.

- The types of status games available to you often depend on your socio-economic status. This explains honour killings, quests for dominance, etc.

- The Hedgehog and the Fox by Isaiah Berlin

- We Are Open Co-op

- The role of endorsement in Open Badges and Open Recognition

Microcast #097 — What do we mean by 'consensus'?

Exploring different conceptions of 'consensus' using polls on the Fediverse and LinkedIn, as well as reflecting on my own experience.

Show notes

Image: Unsplash

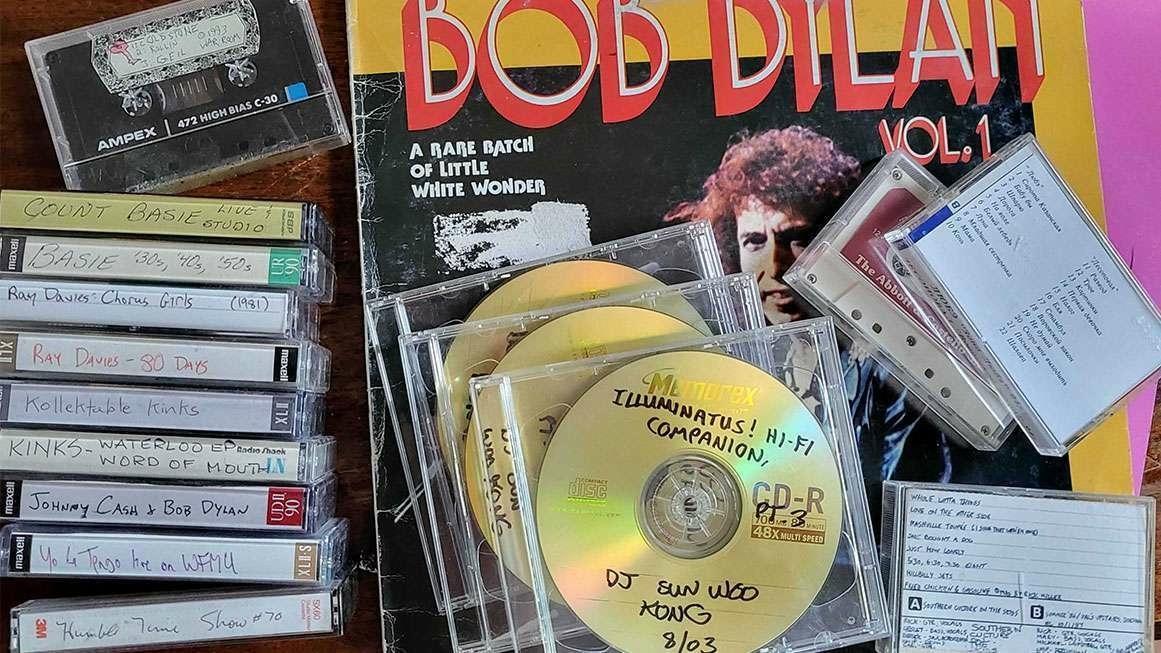

Piracy and the art of cultural archiving

Shortly before Daft Punk’s album Discovery was released, I managed to download a version of it which must have been exfiltrated from the studio. It was subtly different to the version that was released and, to be honest, I preferred it. Sadly, I’ve long since lost the MP3s, and the chance of me finding anything other than the official version these days is minimal.

This article is about the preservation of music, movies, and books. What copyright maximalists don’t realise is that piracy is actually amazing at ensuring that cultural diversity flourishes and is preserved. It’s definitely worth a read.

(It’s also interesting to me how this intersects what I posted earlier about AI-generated music and fandom, because both intersect with ‘official’ narratives and our current understanding of copyright.)

"Your local bookseller cannot creep into your home in the middle of the night and reclaim the contents of your bookshelf," the legal scholars Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz observe in their 2016 book The End of Ownership. "But Amazon exercises a very different kind of practical power over your digital library. Your Kindle runs software written by Amazon, and it features a persistent network connection. That means Amazon can send it instructions—to delete a book or even replace it with a new version—without any intervention from you." The potential for mischief was clear as early as 2009, when someone started selling bootleg Kindle editions of George Orwell's 1984 and Amazon reacted by dispatching even some purchased copies to the memory hole.Source: Online Outlaws Preserve the History of Music, Movies, and Books | ReasonThe fearful mood intensifies whenever politics enters the picture. When books by Agatha Christie, Roald Dahl, and other long-dead authors were reedited to reflect what are said to be “contemporary sensitivities,” many e-books were automatically updated even for readers who had bought them long before. During the George Floyd protests of 2020, several streaming services, unable to stop the abusive policing that set off the unrest, decided instead to edit or eliminate TV episodes where characters appeared in blackface. (This wasn’t an anti-racist gesture so much as a cargo-cult copy of an anti-racist gesture—an elaborate imitation built without figuring out the functions of the component parts—and so it mostly affected shows that had presented blackface with obvious disapproval.) Several songs with words that might offend listeners have gone missing from Spotify or (as with Lizzo’s “Grrrls,” which originally included the term spaz) were replaced with new versions.

Every time news breaks of one of these deletions, a refrain echoes online: Buy physical media! The internet is too impermanent, the argument goes: The real cultural cornucopia was in the outside world.

As is often the case with nostalgia, this leaves out a lot. We still have access to far more media than we did in the days before the mass internet. Yes, this includes that politically controversial material: It takes less than a minute to dig up the unredacted version of “Grrrls” on YouTube (just search for lizzo grrrls spaz), and it’s not hard to find material that was withdrawn from circulation long before the internet era. (I’m told the ’90s were a less politically correct time than today, but back then you needed to track down a bootleg DVD or videotape if you were curious about Song of the South. Now it’s posted on the Internet Archive.) It’s too easy to take the internet’s riches for granted and to forget how much was inaccessible just a few decades ago.

But while we shouldn’t want to return to those pre-web days, there’s something to be said for that online-offline hybrid space where my old tape-trading network dwelled—if not as a world to recreate, then as a way to think about cultural preservation. And there’s something to be said for the bootleggers and pirates. Whether or not they mean to do it, they’re salvaging pieces of our heritage.

Greatest films of all time?

I confess to only having watched one of the top 10 films on this list, which is put together mainly be critics and people who work in the film industry. Must rectify that.

On the other hand, I have watched seven of the top 10 films on the IMDB top 250 list…

In 1952, the Sight and Sound team had the novel idea of asking critics to name the greatest films of all time. The tradition became decennial, increasing in size and prestige as the decades passed.Source: The Greatest Films of All Time | BFIThe Sight and Sound poll is now a major bellwether of critical opinion on cinema and this year’s edition (its eighth) is the largest ever, with 1,639 participating critics, programmers, curators, archivists and academics each submitting their top ten ballot. What has risen up the ranks? What has fallen? Has 2012’s winner Vertigo held on to its title? Find out below.

Fandom and AI generated music

If you haven’t discovered AI-generated songs by your favourite artists, then you’re missing a trick. Try I’m a Barbie Girl by Johnny Cash, for example, or Skyfall by Freddie Mercury. Amazing stuff.

This article is about the fandom around artists such as One Direction and Harry Styles, who are paying hard-earned real money for ‘leaks’ which may or may not be AI-generated music. No-one can tell the difference.

Discord communities within the Harry Styles and One Direction fandom are tearing themselves apart over “leaked snippets” of supposed demo songs that may or may not be AI-generated and are being sold to superfans for hundreds of dollars each.Source: The Specter of AI-Generated ‘Leaked Songs’ Is Tearing the Harry Styles Fandom Apart | 404 MediaThe controversy has turned into a days-long crowdsourced investigation and communitywide obsession, in which no one is really sure what’s real, what’s fake, whether they’re being scammed, or who or what made the songs that they’re listening to.

Over the last few weeks, a flurry of Harry Styles and One Direction snippets—which are short samples of a track designed to prove legitimacy so people will pay of the full thing—have begun popping up on YouTube, TikTok, and, most importantly, Discord, where they are being sold. The problem is no one can tell which, if any, of the songs are real, including AI-analysis companies who listened to the tracks for 404 Media.

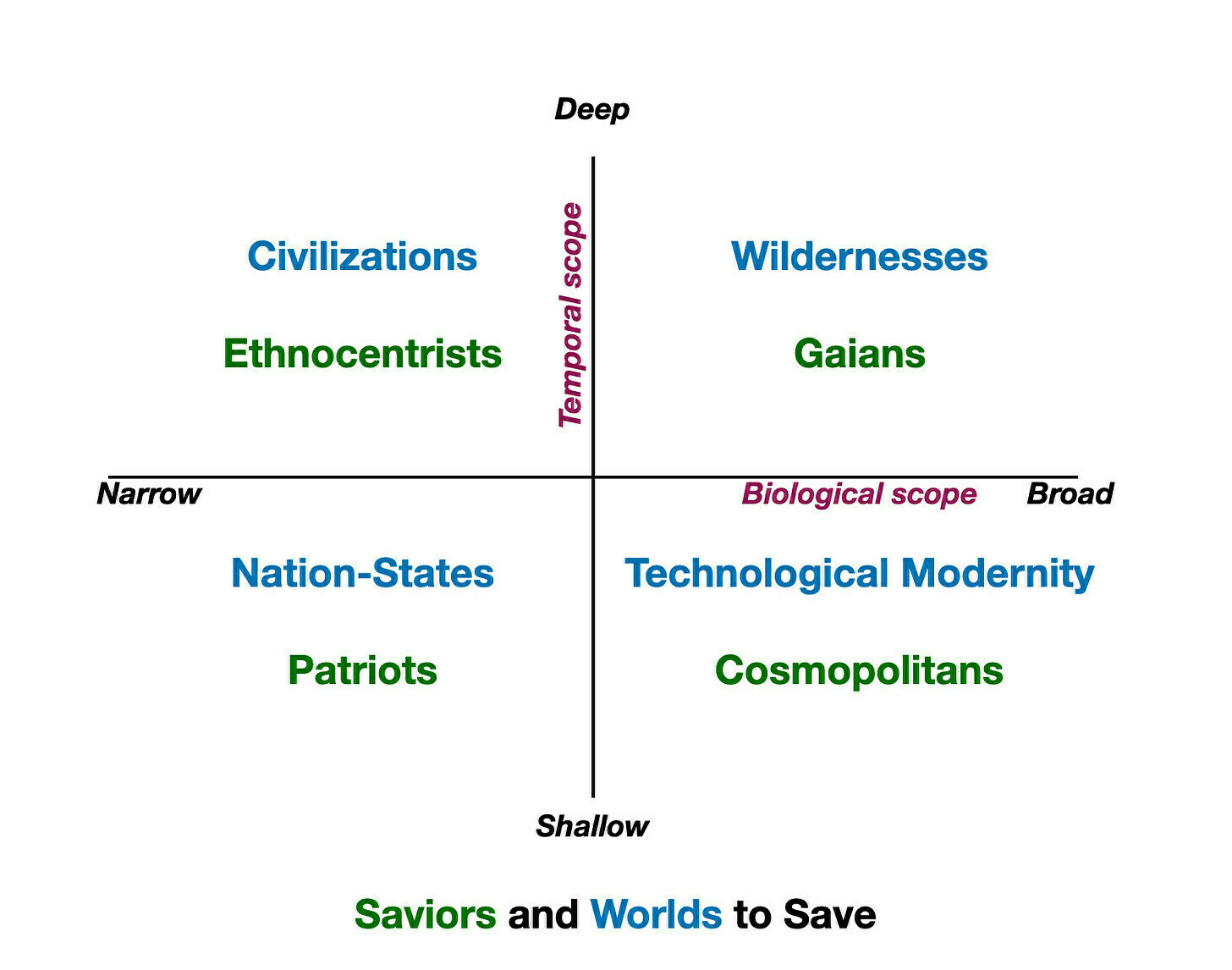

Saving the world using a 2x2 matrix

I’m a fan of Venkatesh Rao’s writing, and in this post he explores what we mean by ‘saving’ when we talk about ‘saving the world’. To do this, he uses a 2x2 matrix, categorising people’s motivations along two axes: biological scope and temporal scope. He identifies four types of “worlds” people aim to save: Civilisations, represented by ethnocentrists; Technological Modernity, represented by cosmopolitans; Modern Nations, represented by patriots; and the World as Wildernesses, represented by Gaians.

Rao himself identifies as a “cosmopolitan with Gaian tendencies,” advocating for a world that is rich in both contemporary technological potentialities and natural history. He argues that the focus should not be on saving the world but on “rewilding” it so that it becomes self-sustaining and doesn’t require saving.

Worlds constructed with biologically narrow scopes (which I’d define as somewhere between family/kinship groups to ethnicities and races, with perhaps a few animal species of cultural significance included, but always falling short of including all of humanity, let alone all of the biosphere) have all sorts of analytical problems that makes them intellectually fragile. But my main problem with them is that they are boringly impoverished to the point of deadness. Even if I could, with careful construction, make them “work” as worlds-to-save, and imagine sustainable futures where they are the entirety of the world, I don’t see the point.Source: What we seek to save when we seek to save the world | RibbonfarmBut apparently, a significant portion of humanity disagrees with me on this front. Many are attracted to the idea that their world-to-save can expand to become all that is; replacing a messy, illegible pluralism with a gloriously insipid and legible monoculture that reigns supreme with a firm, dead hand. I suspect the very intellectual fragility of these worlds is part of their appeal, much as fragility is part of the appeal of house-of-cards games.

[…]

For a cosmopolitan with Gaian tendencies, to save the modern world is to rewild and grow the global web of already slightly wild technological capabilities. Along with all the knowledge and resources — globally distributed in ways that cannot be cleanly factored across nations, civilizations, and other collective narcissisms — that is required to drive that web sustainably. And in the process, perhaps letting notions of civilization — including wishful notions of regulating and governing technology in “human centric” ways — fall by the wayside if they lack the vitality and imagination to accommodate technological modernity.

The complexities of distraction

I really enjoyed this essay by David Schurman Wallace in The Paris Review about being distracted while writing. It reminded me of a much shorter version of one my favourite books about writing: Out of Sheer Rage by Geoff Dyer.

Wallace delves into the complexities of distraction, using Gustave Flaubert’s unfinished novel Bouvard and Pécuchet as a lens to explore how our pursuits, whether intellectual or mundane, often become a chain of distractions. He argues that distraction isn’t necessarily a negative state but could be an essential part of the human condition, a byproduct of our ceaseless quest for knowledge and meaning.

I began writing this essay while putting off writing another one. My apartment is full of books I haven’t read, and others I read so long ago that I barely remember what’s in them. When I’m writing something, I’m often tempted to pick one up that has nothing to do with my subject. I’ve always wanted to read this, I think, idly flipping through, my eyes fixing on a stray phrase or two. Maybe it will give me a new idea.Source: In This Essay I Will: On Distraction | The Paris ReviewIn this moment of mild delusion, I’m distracted. I’ve always wanted to write an essay about distraction, I think. Add it to the laundry list of incomplete ideas I continue to nurse because some part of me suspects they will never come to fruition, and so will never have to be endured by readers. These are things you can keep in the drawer of your mind, glittering with unrealized potential. In the top row of my bedroom bookshelf is a copy of Flaubert’s final novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet. Something about it seems appropriate, though I’m not sure exactly what. I pluck it down.

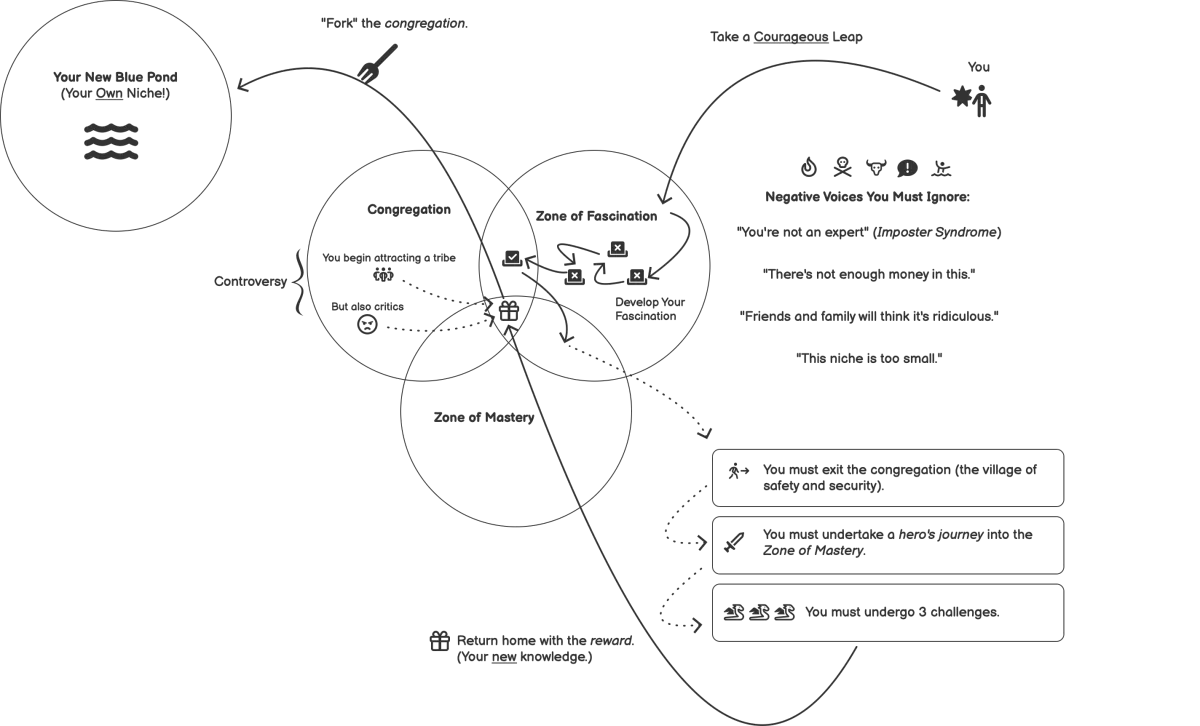

Developing your niche

The website of the guy behind this post is a bit too heavy on the self-marketing for my liking, but I did like the diagram in this post about developing rather than ‘finding’ your niche.

The diagram is contrasted with the kind of Ikigai approach you usually see which, he points out, doesn’t tell you where to actually start.

First, you need to take a courageous leap.Source: It’s Not about Finding Your Niche, It’s about Developing Your Niche | Scott P. ScheperYou need to ignore the negative voices of self-doubt, and you need to ignore feelings of “imposter syndrome.”

Next, you need to begin exploring the odd thing(s) you find fascinating. I call this phase, the “Zone of Fascination.”

Next, you must find a congregation of people who share your irrational fascination. For myself, I found this in r/Zettelkasten.

After this, you need to exit the congregation and go deeper than anyone else in a specific area. You must undergo three challenges. Think of these as “quests” in a hero’s journey.

Monday morning feeling

This is definitely a mood.

Just a cat pondering the meaning of life.Source: Who the Hell Are You? | The New Yorker

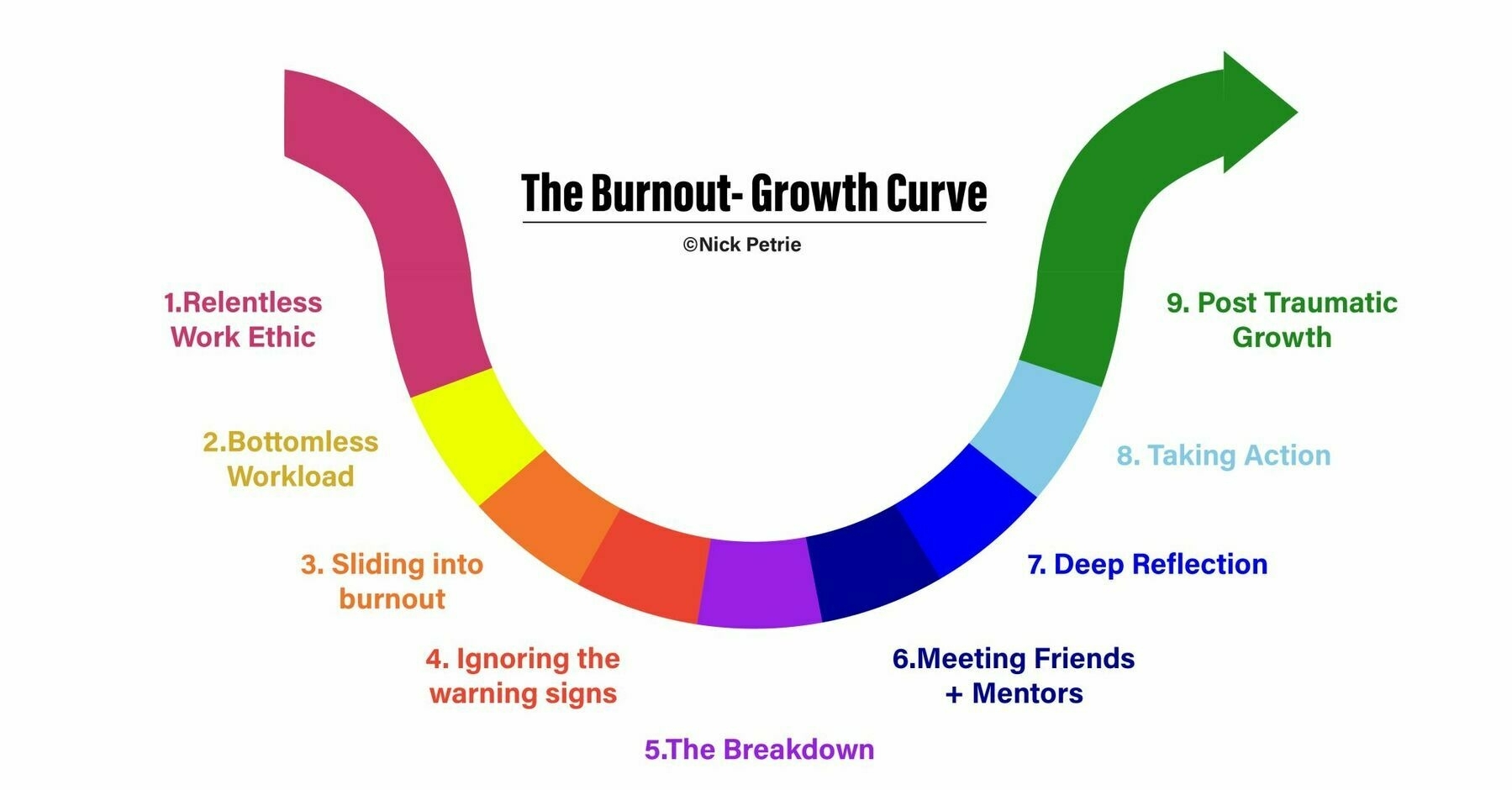

The burnout curve

I stumbled across this on LinkedIn. There doesn't seem to be an authoritative source yet other than the author's (Nick Petrie) social media posts, which is a shame. So I'm quoting most of it here so I can find and refer to it in future.

In terms of my own experience, I slid down that slope pretty quickly in my teaching career, and definitely experienced the 'trap' of going back into a similar situation in a different school. It was also toxic as I had been promoted quickly and, looking back, probably beyond my abilities and experience at the time.

But the great thing about this graphic is that it shows that it's possible to dig your way out, as I did, by realising that a different path is possible. It hasn't always been plain sailing, and there have been other, lesser, traumas since. But I've definitely grown from my earlier experiences, and this is a handy chart to show people who are near the bottom of the curve.

When we interviewed people who had burned out, they told us remarkably similar stories.1. A relentless work ethic – they had a set of beliefs and stories that drove them to work hard - I will deliver, I won’t let people down, I must give 100% at all times.2. Bottomless workload – they joined organizations that rewarded their work ethic with endless work. The harder they worked the more they were given.3. Sliding into burnout – thoughts of work became constant. They had trouble switching off in the evenings, work was taking over their life.4. Ignoring the warning signs – their body was sending signals that something needed to change. They were tense, irritated, exhausted. But they couldn’t slow down – there was too much to do.5. The breakdown – For those who would not listen, the body and brain had a last resort. They shut down. People couldn’t get out of bed, couldn’t drive, couldn’t read. The body refused to go on.The trap for many people is the belief that rest is the solution. So, they took a break – a week, a month or a year. They then went back to the same work, with the same mindset and the same behaviors. They got the same result.The people we interviewed who genuinely overcame burnout followed a common path.6. Meeting friends and mentors – they realized they couldn’t repeat their past. They needed new perspectives and a new approach. They got these from family, peers, coaches, therapists and support groups.7. Deep reflection – they came off autopilot for the first time in years. They reflected deeply on the past – what caused me to burnout? What was driving me? Then the future – what sort of work and life do I want going forward? How can I move myself towards this vision?8. Taking action – they took new actions, sometimes big – change of job, change of career - sometimes small - they set new boundaries, restarted a hobby, got a therapist. Some things helped, some things did not. It didn’t matter. The key thing was they were doing NEW things. They were not repeating their old habits. New actions led to new insights and habits.9. Post traumatic growth – when we interviewed people who took this path 2 years after their burnout, the most surprising thing was how much they had grown from the experience.

Source: Nick Petrie | LinkedIn

Status detection systems

I listened to a fascinating episode of the You Are Not So Smart podcast while out running over the weekend. The focus was on a new book by Will Storr called The Status Game and he was full of insights.

In this episode we welcome back author Will Storr whose new book, The Status Game, feels like required reading for anyone confused, curious, or worried about how politics, cults, conspiracy theories communities, social media, religious fundamentalism, polarization, and extremism are affecting us – everywhere, on and offline, across cultures, and across the world.Source: The game we can’t escape, the psychology behind our perpetual drive to pursue status | You Are Not So SmartWhat is The Status Game? It’s our primate propensity to perpetually pursue points that will provide a higher level of regard among the people who can (if we provoked such a response) take those points away. And deeper still, it’s the propensity to, once we find a group of people who regularly give us those points, care about what they think more than just about anything else.

In the interview, we discuss our inescapable obsession with reputation and why we are deeply motivated to avoid losing this game through the fear of shame, ostracism, embarrassment, and humiliation while also deeply motivated to win this game by earning what will provide pride, fame, adoration, respect, and status.

The punishment for being authentic is becoming someone else’s content

This short piece by Drew Austin reminds me of a couple of links I posted yesterday about Non-places and TikTok’s effect on migration. There are so many quotable parts, including that when it comes to social media, “the only place left to go is outside”.

What I think is interesting is how online and offline used to be seen as completely separate. Then we realised the impact that offline life had on online life, and now we’re seeing the reverse: Instagram, TikTok, etc. having a huge impact on the spaces in which we exist offline.

“In the next few years,” Kyle Chayka tweeted yesterday, “the last desperate search for shreds of authentic local culture will convulse the globe as the internet consumes every interesting quirk and scales it up to the size of TikTok.” That all-too-plausible prediction fits well alongside Chayka’s concept of AirSpace and his observations about overtourism, each examining how social media has come to shape the physical world (or at least vent its noxious exhaust there) instead of merely reflecting it. If AirSpace represents the homogenizing tendency of globally scaled algorithmic platforms like Instagram and Airbnb, which herd everything they touch into aesthetic alignment, then TikTok’s impact seems like the opposite: the cultivation and amplification of difference by a desperate horde of content creators scouring the ends of the earth for new material. The latter ultimately has the same entropic effect as the former, reframing local nuances as temporary viral microtrends that diffuse through culture, form the basis for a thinkpiece or two, and then recede back to their original modest scale. This may be ephemeral but it is pervasive and ongoing. In the contemporary landscape, the punishment for being authentic is becoming someone else’s content.Source: I’m Beginning to See the Light | Kneeling Bus[…]

The illusion that the internet and “real life” are two separate universes has been thoroughly dispelled by now, but the nature of their interaction is complex and evolving. The social media era seems to have already peaked, as I predicted at the end of last year, calling our present moment a “saturation point of cultural self-consciousness that represents the fullest possible synthesis of reality and our digitally mediated perception of it.” The metaverse concept was dead on arrival; there’s nowhere left to go but outside. And that’s what we’re doing: TikTok is the social network for the internet’s decadent era, embodying the worldview that becoming viral content is the highest calling, the end state to which everything aspires and strives. You visit Italy not to enjoy yourself but to help Italy fulfill its destiny as a meme.

Job crafting, identity, and fulfilment

This article by Lan Nguyen Chaplin, a professor of marketing at a prestigious business school, reflects my own experience. Those jobs I’ve thought were ‘big’ and ‘important’ have been the ones that have drained me of energy, made me sad, and generally changed me for the worse.

Instead, as Chaplin says, the important thing is to align your work your values and personal strengths. This (eventually) allows you to transform what you do into a sustainable, balanced, and purposeful career. Sometimes, though, you have to know what you’re willing to tolerate and what you’re not, which can involve going precipitously close to the fire.

Outside of my fancy new title, I had begun to feel empty. In just a few months, my identity had quite literally become “my job” and I lost sight of the many things that fulfilled me outside of it. I didn’t have time or energy for family and friends. Activities that brought me joy, like running and lacrosse, went out the window. I traveled for work instead of pleasure. I had no time to give back to my community.Source: What You Should Chase Instead of a Dream Job | AscendInstead, I jotted down research ideas on bar napkins, replied to emails when everyone else was offline, and had a growing portfolio of projects in development. I didn’t know how to disconnect without feeling unproductive. For hours, I sat with my laptop in isolation, working on research that might never be published.

[…]

The moment you have found your dream job is the moment you have stopped growing, evolving, and finding new ways to experience joy in your role. Remember, you were hired because you offer something the organization is missing. They need change. They need you to bring your whole self to work, and that means doing things differently with the added flare that is you. A job that inspires you and gives you the space you need to be your full self is the dreamiest job out there.

AI writing detectors don’t work

If you understand how LLMs such as ChatGPT work then it’s pretty obvious that there’s no way “it” can “know” anything. This includes being able to spot LLM-generated text.

This article discusses OpenAI’s recent admission that AI writing detectors are ineffective, often yielding false positives and failing to reliably distinguish between human and AI-generated content. They advise against the use of automated AI detection tools, something that educational institutions will inevitably ignore.

In a section of the FAQ titled "Do AI detectors work?", OpenAI writes, "In short, no. While some (including OpenAI) have released tools that purport to detect AI-generated content, none of these have proven to reliably distinguish between AI-generated and human-generated content."Source: OpenAI confirms that AI writing detectors don’t work | Ars Technica[…]

OpenAI’s new FAQ also addresses another big misconception, which is that ChatGPT itself can know whether text is AI-written or not. OpenAI writes, “Additionally, ChatGPT has no ‘knowledge’ of what content could be AI-generated. It will sometimes make up responses to questions like ‘did you write this [essay]?’ or ‘could this have been written by AI?’ These responses are random and have no basis in fact.”

[…]

As the technology stands today, it’s safest to avoid automated AI detection tools completely. “As of now, AI writing is undetectable and likely to remain so,” frequent AI analyst and Wharton professor Ethan Mollick told Ars in July. “AI detectors have high false positive rates, and they should not be used as a result."

Microcast #096 — Getting back in the saddle

Explaining what I've been up to and the difference between being a hedgehog and a fox.

Show notes

Image: Pexels

Non-places

I’m a big fan of Guy Debord’s work but have never read that of Marc Augé, who came up with the concept of ‘non-places’. These are spaces like airports and hotels where human interaction is largely transactional, leading to a form of psychic isolation.

This article outlines Augé argument that to counteract the dehumanising effects of these non-places, individuals should engage in active observation, storytelling, and even talking to strangers. In this way we essentially become ‘supermodern flaneurs’, restoring a social element to these otherwise isolating spaces.

Augé was keen to explain how the transformations of the contemporary world had made anthropology more complicated. “We are in an era characterized by changes of scale,” he wrote. “Images of all sorts, relayed by satellites and caught by the aerials that bristle on the roofs of our remotest hamlets, can give us an instant, sometimes simultaneous vision of an event taking place on the other side of the planet.” So far, so postmodern; what Augé called the “acceleration” of events is an idea that crops up repeatedly in political theory. The specifically supermodern condition that he identifies is the dominance of non-places.Source: Non-places are robbing us of life | UnHerdWe live in “a world where people are born in the clinic and die in hospital, where transit points and temporary abodes are proliferating under luxurious or inhuman conditions” — from “hotel chains and squats, holiday clubs and refugee camps”. In non-places, exchange between human beings is transactional: you buy a sandwich, or a massage, or a train ticket. Speech is replaced by text; signs direct behaviour, instead of people, giving instructions and advertising products. We are, therefore, isolated, in “a solitude made all the more baffling by the fact that it echoes millions of others”.

TikTok's algorithm and its effect on migration

Kukes, Albania is one of the poorest cities in Europe. Since the end of pandemic lockdowns, the city has seen a sharp rise in the number of Albanians, especially men, seeking asylum in the UK.

This article is a real eye-opener as to what’s going on, and talks about everything from TikTok propaganda to criminal gangs and cannabis houses. Well worth a read, especially to show the other side of the “small boats” rhetoric.

In 2022, the number of people leaving Albania for the U.K. ticked up dramatically, as well as the number of those seeking asylum, at around 16,000, more than triple the previous year. According to the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, one reason for the uptick in claims may be that Albanians who lack proper immigration status are more likely to be identified, leading them to claim asylum in order to delay being deported. But Albanians claiming asylum are also often victims of blood feuds — long-standing disputes between communities, often resulting in cycles of revenge — and viciously exploitative trafficking networks that threaten them and their families if they return to Albania.Source: The Albanian town that TikTok emptied | Coda StoryBy 2022, Albanian criminal gangs in Britain were in control of the country’s illegal marijuana-growing trade, taking over from Vietnamese gangs who had previously dominated the market. The U.K.’s lockdown — with its quiet streets and newly empty businesses and buildings — likely created the perfect conditions for setting up new cannabis farms all over the country. During lockdown, these gangs expanded production and needed an ever-growing labor force to tend the plants — growing them under high-wattage lamps, watering them and treating them with chemicals and fertilizers. So they started recruiting.

Everyone in Kukes remembers it: The price of passage from Albania to the U.K. on a truck or small boat suddenly dropped when Covid-19 restrictions began to ease. Before the pandemic, smugglers typically charged 18,000 pounds (around $22,800) to take Albanians across the channel. But last year, posts started popping up on TikTok advertising knock-down prices to Britain starting at around 4,000 pounds (around $5,000).

People in Kukes told me that even if they weren’t interested in being smuggled abroad, TikTok’s algorithm would feed them smuggling content — so while they were watching other unrelated videos, suddenly an anonymous post advertising cheap passage to the U.K. would appear on their “For You” feed.

Walking 1,000 miles across Europe

As I know from personal experience, walking a long way by yourself is hard work, both mentally and physically. As this article points out, doing so as a woman is even harder, so good on Lea Page for not only walking a thousand miles across Europe, but writing about how the biggest danger is… men.

When I walk alone, the consequences of every good or bad choice I make fall entirely on me: a responsibility and a freedom. As a woman and a mother, I rarely only have to consider what I want and need without having to first attend to other people. I know there are risks, but each time I come out of that “forest”, I feel stronger and more confident. Weighed against the simple daily rhythms of a long-distance walk and the joy and wonder I experience, risk – reasonable risk – becomes a small part of the equation, and one I am willing to accept.Source: I walked 1,000 miles alone through Europe – and learned that fear is the price of freedom | The Guardian[…]

One other time, while walking along a river just outside Colle di Val D’Elsa in Tuscany, I felt that familiar clench of panic. This river, a glacial robin’s-egg blue, meandered and tumbled gently. The gorge was not deep, but a lonely wooded path just outside a city struck me as the perfect place for an ambush. Clearly, men exist everywhere, so it made no sense to be frightened in that one particular place. I knew that, statistically, women are safer out in the world than they are at home, but in that moment, knowledge felt like thin protection. Unable to shake my feelings of dread, I called my husband, and we talked about inconsequential things so I could hear his sleepy voice and keep putting one foot in front of another.

And that’s what women are really talking about when we talk about being afraid. We are talking about men. But there is, I learned, a difference between being afraid and being unsafe.

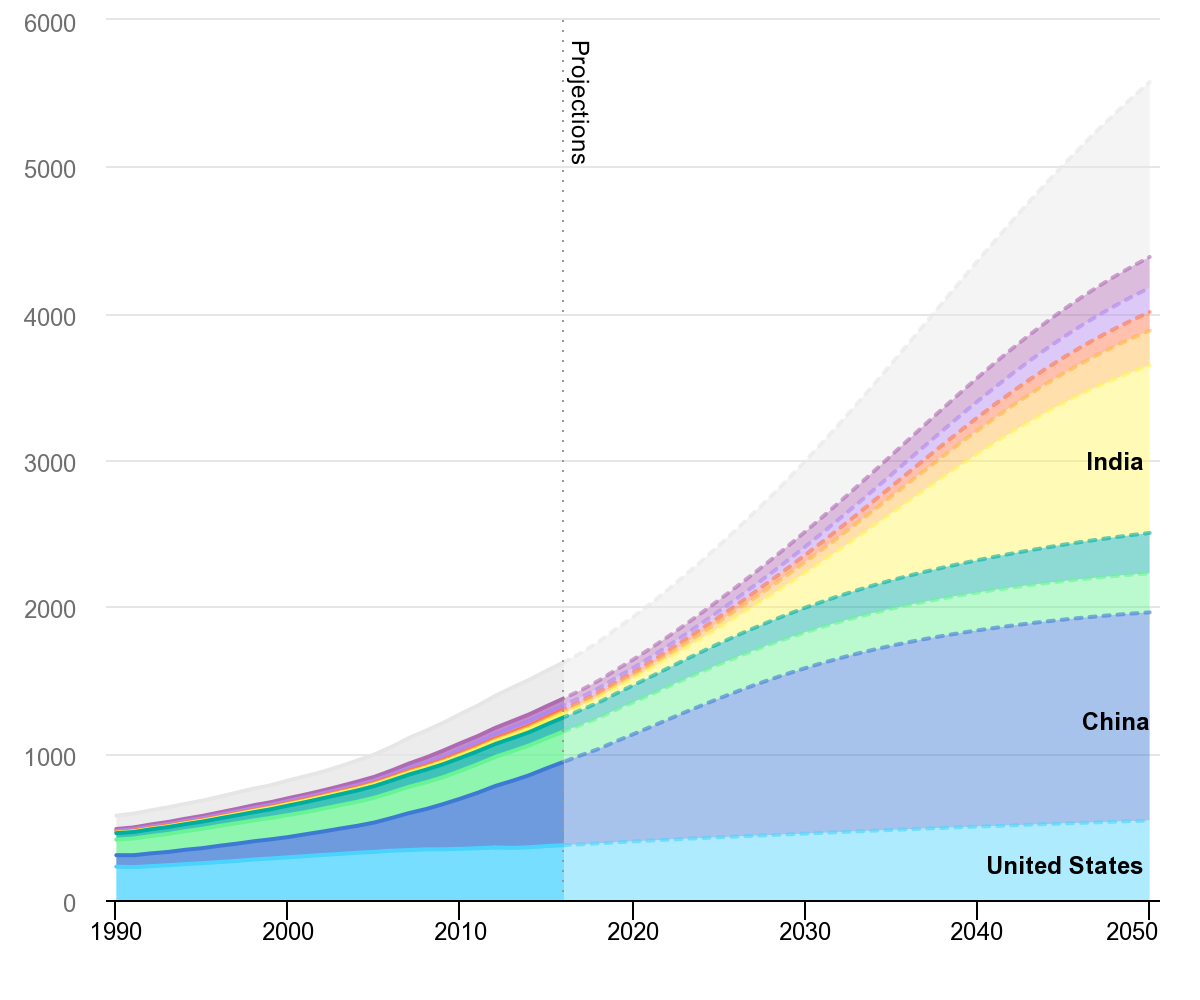

Cooling down is hotting up

As the world heats up, humans are going to need to cool down. The use of air conditioning already accounts for nearly 20% of electricity used in buildings worldwide, so this report highlights the urgent need for higher efficiency standards in cooling technologies to mitigate the strain on energy systems and reduce emissions.

Apparently, effective policies could halve future energy demand and cut costs by $3 trillion by 2050. More importantly than the financial impact, I guess, more efficient air conditioning means that less hot air is dumped into urban environment, which tends to create heat islands (and affects weather patterns).

Cooling down is catching on. As incomes rise and populations grow, especially in the world’s hotter regions, the use of air conditioners is becoming increasingly common. In fact, the use of air conditioners and electric fans already accounts for about a fifth of the total electricity in buildings around the world – or 10% of all global electricity consumption.Source: The Future of Cooling | IEAOver the next three decades, the use of ACs is set to soar, becoming one of the top drivers of global electricity demand. A new analysis by the International Energy Agency shows how new standards can help the world avoid facing such a “cold crunch” by helping improve efficiency while also staying cool.

Indigenous knowledge, sustainable design, and long-term thinking

This is a perfect example of the kind of sustainable design and long-term thinking we lose when we ignore indigenous knowledge.

In Western Australia, Marri trees, known as Gnaama Boorna in the Menang language, have been pruned by Aboriginal people for generations to collect and store rainwater. The ancient practice involves shaping the trees into a bowl-like structure, making them vital water sources in areas where water is scarce, and they are often found in ceremonial areas or high hills.

Source: Specially pruned for centuries in WA, marri trees provide a vital source of water for traditional owners | ABC NewsGnaama, meaning hole for water, and Boorna, meaning tree or timber.

[...]By pruning and trimming parts of specific trees as they grow, traditional owners encourage them to take on a unique, bowl-like shape — helping collect and store rain water.

Some advice for readers

Less ‘rules’ than notes, this post by Ryan Holiday (himself a prolific author) is worth reading. I like the part where he turns the tables, “You say you don’t have time to read but what does the screen time app on your phone say? What does your calendar say?"

Along the way, Holiday emphasises the importance of a systematic approach over speed reading, advocates for physical books, note-taking, and seeking wisdom rather than mere facts. He also encourages readers to share impactful books with others. (You can check out my reading list and reviews here.)

So the question I am asked most often is:Source: These 38 Reading Rules Changed My Life | RyanHoliday.netHow do you read so much? What’s the secret?

The answer is not “I’m a speedreader.” As I’ve written before, speed reading is a scam. The answer is that I have a system, a process that helps me be a productive reader. It’s not my system exactly, as I’ve taken many strategies from history’s greatest readers. Nor is this a system designed around speed or quantity. Reading is wonderful in and of itself, why would I try to rush through it? No, I try to do it well. I try to enjoy it.