2023

- The Value of Credentials Endorsement

- The role of endorsement in Open Badges and Open Recognition

- Endorsement using Open Badges and Community Recognition

- capitalism is dominated by the rich, who set the political agenda;

- capitalism leads to growing inequality;

- capitalism promotes selfishness and greed; and

- capitalism leads to monopolies.

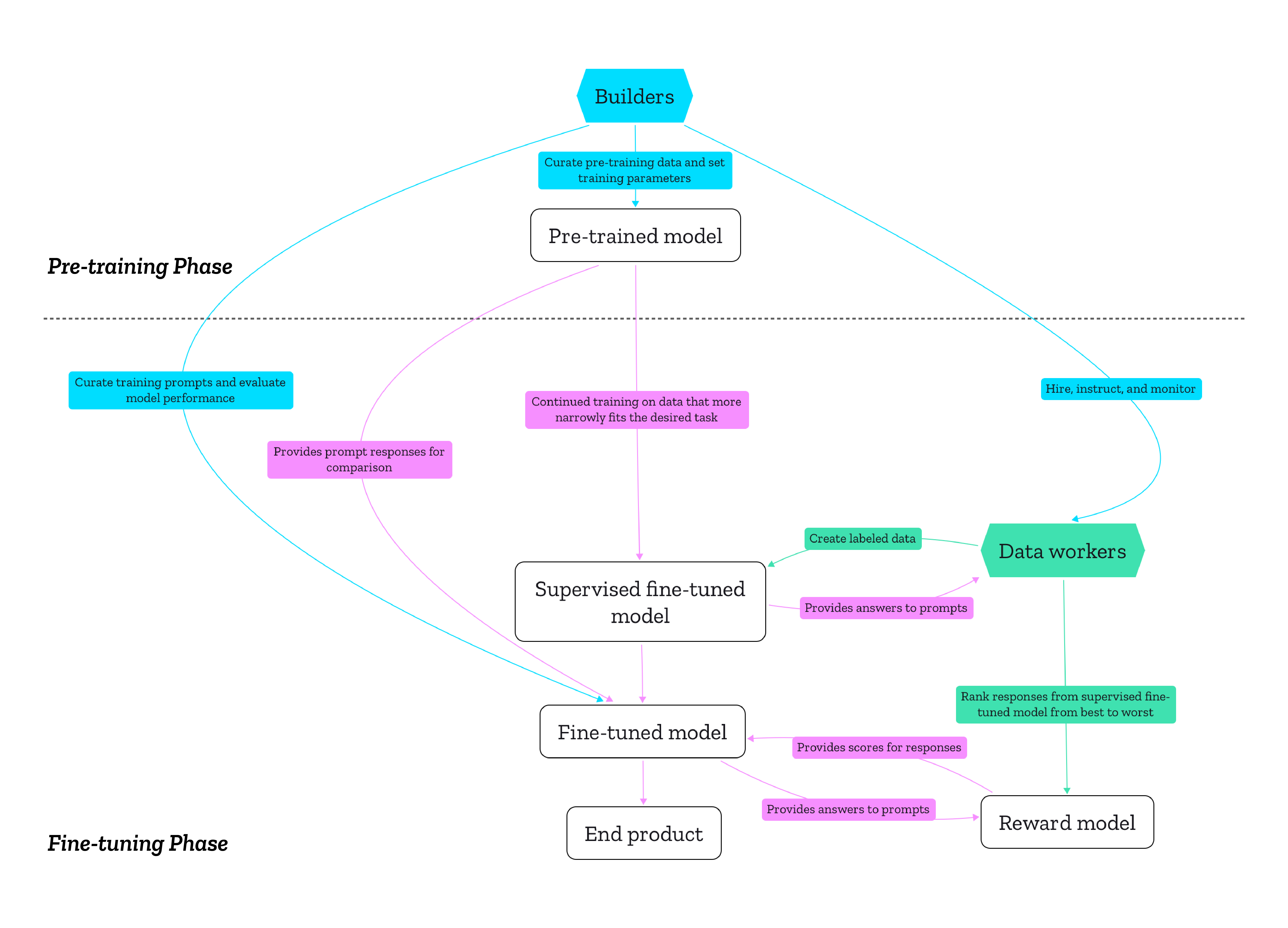

If LLMs are puppets, who's pulling the strings?

The article from the Mozilla Foundation surfaces into the human decisions that shape generative AI. It highlights the ethical and regulatory implications of these decisions, such as data sourcing, model objectives, and the treatment of data workers.

What gets me about all of this is the ‘black box’ nature of it. Ideally, for example, I want it to be super-easy to train an LLM on a defined corpus of data — such as all Thought Shrapnel posts. Asking questions of that dataset would be really useful, as would an emergent taxonomy.

Generative AI products can only be trustworthy if their entire production process is conducted in a trustworthy manner. Considering how pre-trained models are meant to be fine-tuned for various end products, and how many pre-trained models rely on the same data sources, it’s helpful to understand the production of generative AI products in terms of infrastructure. As media studies scholar Luke Munn put it, infrastructures “privilege certain logics and then operationalize them”. They make certain actions and modes of thinking possible ahead of others. The decisions of the creators of pre-training datasets have downstream effects on what LLMs are good or bad at, just as the training of the reward model directly affects the fine-tuned end product.Source: The human decisions that shape generative AI: Who is accountable for what? | Mozilla FoundationTherefore, questions of accountability and regulation need to take both phases seriously and employ different approaches for each phase. To further engage in discussion about these questions, we are conducting a study about the decisions and values that shape the data used for pre-training: Who are the creators of popular pre-training datasets, and what values guide their work? Why and how did they create these datasets? What decisions guided the filtering of that data? We will focus on the experiences and objectives of builders of the technology rather than the technology itself with interviews and an analysis of public statements. Stay tuned!

Bad historical maps

Like the author of this article, I love a good map. Whether it’s trekking across hills and mountains with an OS map, or looking through historical maps, there’s something enchanting about understanding territories.

The thing is, though, that maps are literally projections. They leave things out and therefore have to be interpreted. If the maps are out of date, or are being used in a way that’s anachronistic, that leads to a huge problem.

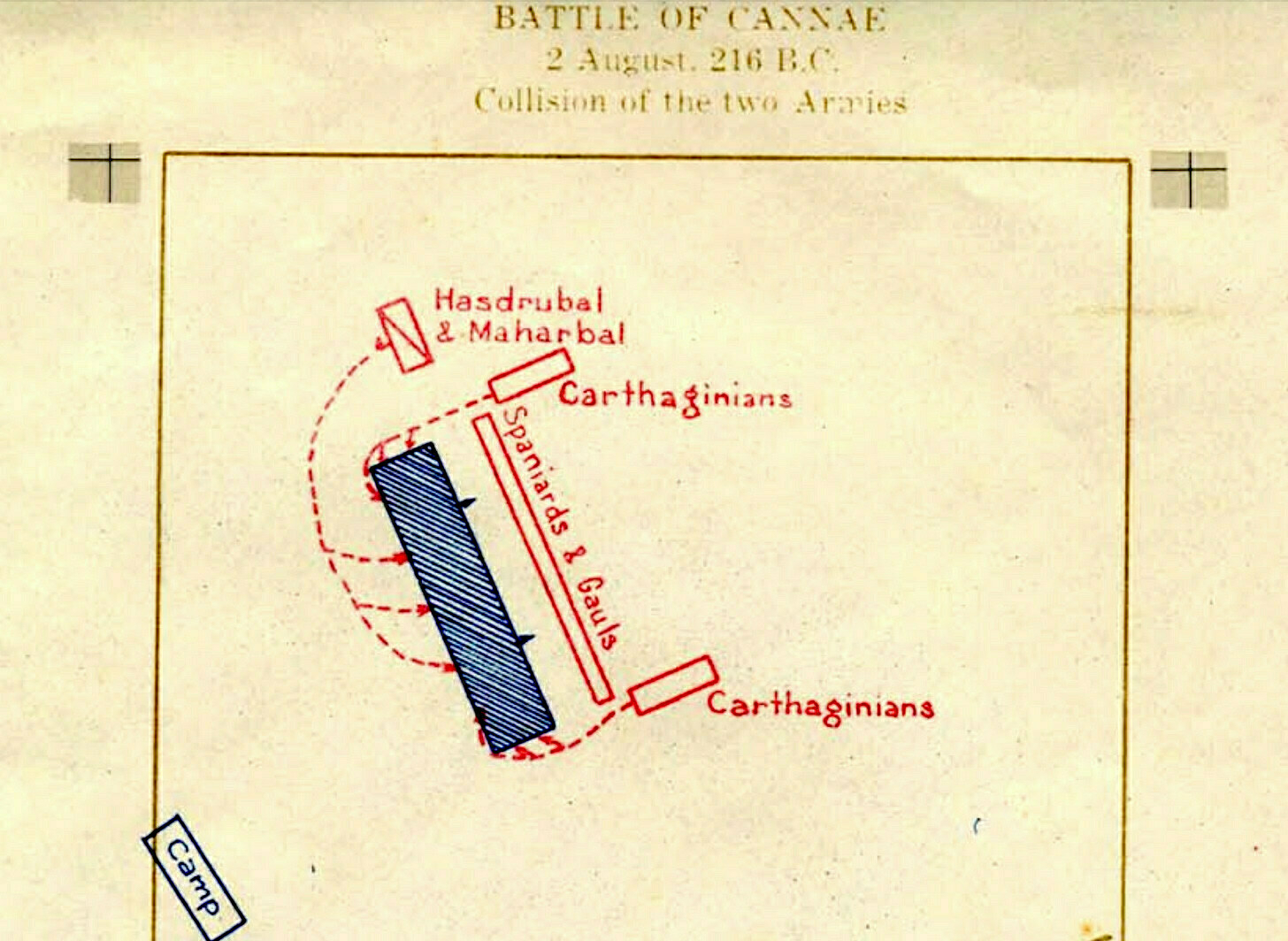

As a History teacher, I used to teach WWI but didn’t know that General von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff, was obsessed with Hannibal and the Battle of Cannae. Apparently he used stories and maps of how it played out to inform his strategy. The problem was that, not only did it happen a couple of millennia beforehand, but it probably didn’t even play out that way.

Maps like this are a big part of why I became a historian. I probably spent more time looking through the volumes of Colin McEvedy’s Penguin Atlas of History series than any other book when I was a kid.... There’s something beguiling about the thought that a simple arrangement of lines might explain the world — like seeing human history as an enormous game of Civilization 6. But of course, that’s also the problem with using maps as a way of understanding history. If you’re not careful, they go from being helpful tools to misleading simplifications.Source: Historical maps probably helped cause World War I | Res Obscura[…]

In her book The Guns of August, Barbara Tuchman argues that the memory of Cannae, which was passed down through a succession of military histories until it became a virtual obsession of strategists in the 19th century, helped push the world into an unimaginable catastrophe.

It did so by offering up a model of a “battle of annihilation” that Germany’s war planners believed they could unleash on France. At the head of these planers was General von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff. The map of Cannae haunted Schlieffen’s dreams.

[…]

Cannae was no vague inspiration. It was a direct model for Germany’s invasion of Belgium and France.

[…]

As the historian Martin Samuels pointed out in his article “the Reality of Cannae,” there is no archaeological evidence for the battle. Nor are there first-hand sources of any kind. Everything we know derives from accounts written sixty years or more after Cannae itself. Suffice to say, when Samuels dug into these sources, he found as many questions as answers. The detailed maps of movements at Cannae that decorated military strategy manuals for hundreds of years, in other words, were largely fanciful. Samuels calls Cannae “the most quoted and least understood battle” in history.

The simplicity of a historical map — the clear labels, the sharp edges, and above all the reduction of thousands or millions of people into abstract symbols — is a big part of why they’re so beguiling. But it’s also why they lead us astray.

[…]

It is sometimes said that the map is not the territory. The map is not the historical argument, either.

Instead, maps are a great way to pose questions about history. They are best approached as a way in: an entry-point rather than an ending. They offer one path toward confronting the enormous complexity of “real” history — the kind made by individual people, on the decidedly imperfect and unmap-like terrain of the world.

More treasures and secrets from ancient Egypt

Underwater archaeologists have discovered a sunken temple off Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, filled with artefacts related to the god Amun and the goddess Aphrodite. The temple was part of the ancient port city of Thonis-Heracleion, which sank due to a major earthquake and tidal waves.

When we discover the remnants of civilizations buried under the sea and in other places it does make me think about humans in the future discovering what we leave behind. What will they think?

While exploring a canal off the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, underwater archaeologists discovered a sunken temple and a sanctuary brimming with ancient treasures linked to the god Amun and the goddess Aphrodite, respectively.Source: Sunken temple and sanctuary from ancient Egypt found brimming with ‘treasures and secrets’ | Live ScienceThe temple, which partially collapsed “during a cataclysmic event” during the mid-second century B.C., was originally built for the god Amun; it was so important, pharaohs went to the temple “to receive from the supreme god of the ancient Egyptian pantheon the titles of their power as universal kings,” according to a statement from the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology (IEASM).

[…]

Also at the site divers found underground structures supported by “well-preserved wooden posts and beams” that dated to the fifth century B.C., they wrote in the statement.

[…]

The sanctuary also held a cache of Greek weapons, which could indicate that Greek mercenaries were in the region at one time “defending the access to the Kingdom” at the mouth of the Nile’s westernmost, or Canopic, branch, the researchers said in the statement.

Death, wrecks, and harsh weather

There was a time, about a decade ago, where although I was based from home, I’d be travelling pretty much every week for work. I was abroad once a month at least.

These days, perhaps with the pandemic as a catalyst, I’m slightly more wary of travelling. It’s probably also a function of age and awareness of how routines affect my body. As an historian, though, I’ve always been amazed by those people who journeyed long distances.

This post by an academic historian of medicine and the body outlines some of the dangers such travellers faced. Pretty amazing, when you think about it.

Unlike today, when it’s entirely possible to have breakfast in London, lunch in Milan and be back at home in time for supper, travel in the early modern period was no easy undertaking. More than this, it was widely acknowledged to be inherently dangerous. What, then, were the perceived risks? Even a brief survey tells us a lot about how travel was regarded in health terms.Source: The Health Risks of Travel in Early-Modern Britain | Dr Alun WitheyFirst was the risk of accident or death on the journey. In the seventeenth century even relatively short distances on horseback or in a carriage carried dangers. Falls from horses were common, causing injury or even death.

[…]

Travel by sea, even around local coasts, carried its own obvious risks of storm and wreck. So common and widely acknowledged were the vagaries of sea travel that a common reason for making a will in the early modern period was just before embarking on a voyage.

[…]

Once abroad, too travellers were at the mercy of a bevy of dangers, from unfamiliar territories and extreme landscapes to harsh weather and climate, their safety contingent on the quality of their transport and the reliability of their guides.

[…]

Even ‘foreign’ food and drink could be risky. Thomas Tryon’s Miscellania (1696) noted the dangers of ‘intemperance’ and of misjudging the effects of climate upon the body in regard to drinking alchohol [sic]

Microcast #98 — Endorsement

The introduction to some thoughts on endorsement using Open Badges and Verifiable Credentials within networks of trust.

Show notes

Image: Unsplash

Virtual spaces for learning and collaboration

Today, I’ve been doing a UCL short course. As we were coming back from a break, we were discussing the lack of ‘embodiedness’ in virtual interactions. This reminded me of experiments with different platforms that WAO did during the pandemic.

This post by Alja from Tethix is prompted by a challenge-based learning platform that I took part in last year. They’re focusing on tech ethics (hence the name) and their approach was great. It was just that the tools got in the way to some extent.

I think, after reading this, it’s time to experiment again with some of the tools mentioned in the post. Sometimes you do need a sense of play and feel like you’re connected in ways that go beyond small boxes on a screen.

The Tethix Archipelago emerged from the Challenge Based Learning pilot we did in March last year. For the pilot, we designed a unique collaborative online learning experience in tech ethics and used Mural collaborative whiteboards and visual storytelling to situate the learning journey in a fictional world: the Tethix Archipelago. The Archipelago consists of four islands that emerged from the four essentials skills of the Challenge Based Learning journey: collaboration, exploration, practice, and reflection.Source: Welcome to the Tethix Archipelago | TethixMural turned out to be a great tool for collaboration and live session guidance, but it didn’t really convey a sense of place. Clicking on a link in a Mural to visit the next leg of your journey just doesn’t feel like traveling, especially when you’re trapped in the same little Zoom box during every live session.

So we started exploring tools that could help us convey a sense of space and discovered Gather and WorkAdventure, among others. These tools offer two-dimensional virtual collaborative spaces where you can walk around a space with your avatar and have proximity-based conversations by using your microphone and camera.

[…]

You might be thinking: this is cute and all, but is this Archipelago all games and play? Well, playfulness is a big part of why we’re experimenting with these game-like worlds; we know that play helps us learn better and can unlock our imagination. But there’s much more to it than just millennial nostalgia for pixel graphics.

As already mentioned, Gather allows us to build a sense of place, both inside rooms and between them. And a sense of place helps with learning and memory encoding. Historical records show ancient Greeks using the method of loci or memory palaces, a technique for improving memory encoding and retrieval, and humans have been developing other mnemonic techniques based on spatial relationship for much longer than that. We’re physical beings, uniquely equipped to understand space, whether physical or represented by pixels.

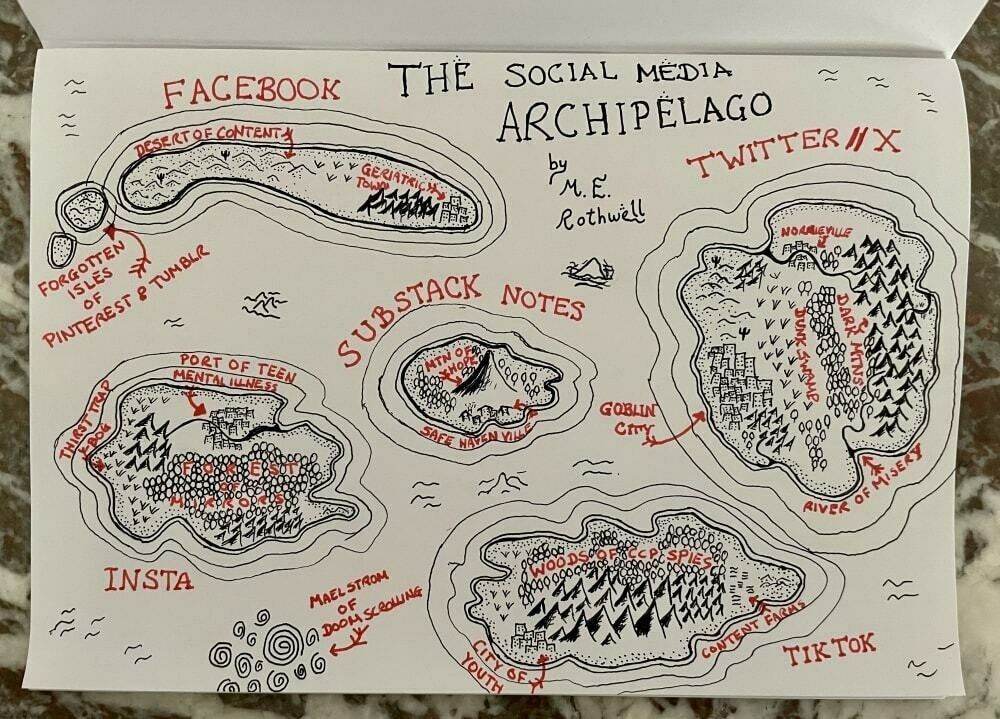

The Social Media Archipelago

On 1st October, I’ll be transitioning the Thought Shrapnel newsletter to Substack. More about that here. What’s interesting is the ecosystem that’s being created there — including Substack Notes, which is where I came across this post.

I’ve several things to say about this hand-drawn map of the ‘social media archipelago’. First, as the top commenter on the post notes, it’s similar to a classic xkcd cartoon from 2007 and shows how much the landscape has changed.

Second, Chelsea Troy quite rightly points out that we’ve got a Twitter-shaped hole in the internet, which people are filling with either private communities (Slack/Discord), the Fediverse (Mastodon, etc.), or Twitter-like things (Bluesky, etc.)

What I think they’re missing is.. Substack Notes. For someone who loves reading and writing, it’s full of interesting people sharing thoughtful things. You can find my notes here.

To anyone looking to navigate the ongoing perils of social media, it can be a challenging and daunting task. An adventure marked by intense trepidation and foreboding, by fear and doubt. But worry no longer, I have drawn a map.Source: Note by M. E. Rothwell on SubstackI present to you, The Social Media Archipelago.

Whether you’re lost among the Musky Mountains or the Dunk Swamps of Twitterland, or in the selfie-obsessed Forest of Mirrors on the Isle of Insta, I hope this chart can be a helpful guide on your journey. Never again be stranded among the bleak deserts of Facebook, no interesting content in sight. Never again be sucked into the maelstrom of the Doomscroll, forever locked among the whirlpools of cheap dopamine hits.

Instead, look toward the lone peak of innocent hopes, reminiscent of the heady days of the early internet, where healthy conversation and good faith debate may yet flourish. Look to the terra novalis, known to the early cartographers as the mythical land of Substackus Notum.

Or in the common tongue — Substack Notes.

(it was a slow day at work ok)

This isn't working. Can we talk about that?

Thankfully, there’s no-one calling me back into the office. But this post is about people who are being recalled — as well as those working in sub-optimal remote settings.

This post suggests that the phrase “this isn’t working” should be viewed as an invitation for dialogue rather than a threat, arguing that open communication is crucial for things inadequate in the workplace.

The Future of Work conversation is full of rejected gifts. We've seen bosses throw "this isn't working" back in employees' faces as "entitlement." As "millennials." As "no one wants to work anymore." We've seen employees throw it back in their CEO's face, too, as "outdated." Or "boomers." Or "something something commercial real estate." As far as we can tell, that point-scoring hasn't gotten us any closer to the future we're all trying to build.Source: Sorry I’m getting kicked out of this room | Raw Signal GroupWe know that everyone’s sick of constantly redesigning the rules of work. There’s this revisionist nostalgia for, in some quarters, 2019. And in others, 2021. We know that some of you have built systems here in 2023 that are working for you, and you would like them to please just stay put for a goddamned minute. We get that. But when someone tells you that those systems aren’t working for them, shouting them down won’t give you the peace and quiet you want.

[…]

By all means, read what other orgs are doing. Maybe there are things you can learn from what Apple does, or Google, or Smuckers. But there’s no shortcut around the conversation. Every sales person, fundraiser, marketer, product leader, and designer will tell you the same thing. You have to talk to people to know if you’re actually reaching them. To know if any of your solutions actually solve the problem.

Constructs, meta-constructs, and shared cognitive spaces

Posts like this one by Venkatesh Rao are like catnip to me. He explores the concept of the ‘real world’ as a construct shaped by collective human beliefs and values, arguing that it is, of course, anthropocentric and inherently absurd.

All worlds created by humans, such as fandoms and nationalisms, have more or less consequence in shaping the ‘real world’. In other words, there are constructs which serve to help shape the meta-construct. This, in essence, is a shared cognitive space for humans.

Well worth reading if you’re in the mood to question the nature of reality, explore the power of collective belief, and ponder the transient nature of what we consider to be ‘real’. It’s a complex examination of how human perception shapes the world we live in, and how that world, in turn, shapes us.

Accounting for consciously shared worlds like religions, fandoms, and nationalisms, as well as commonalities that arise from obvious and lazy lines of thought or imitation, there are perhaps a few thousand to tens of thousands of non-trivial distinct inhabited worlds out there. Of these, perhaps a few hundred are significant enough to require accounting for in any analysis. The rest are, at best, butterflies flapping in the chaotic weather-systems of history, hoping to cause hurricanes.Source: This is the New Real World | Venkatesh RaoOf the few hundred that are significant, perhaps a couple of dozen matter strongly, and perhaps a dozen matter visibly, the other dozen being comprised of various sorts of black or gray swans lurking in the margins of globally recognized consequentiality.

This then, is the “real” world — the dozen or so worlds that visibly matter in shaping the context of all our lives, with common knowledge of such shaping constituting a non-trivial part of the visibly mattering. The consequentiality of the real world is partly a self-fulfilling prophecy of its own reality. Something that can play the rule of truth. For a while.

[…]

The real world, in other words, is a fragile, unreliable, dubious, borderline incoherent, unsatisfying house of cards destined to die. Yet, while it lives and reigns, it is an all-consuming, all-dominating thing. A thing that can seem extraordinarily real compared to any more fragile, value-based private delusions we may harbor. To the point that we typically refer to it unironically as the real world, to be contrasted with self-indulgent fantasies, and characterize belief in it as pragmatism rather than just a grittier delusion.

Image: Marcus Spiske

Research shows people in most countries are anti-capitalist

I came across this via fellow Sunderland AFC supporter Andrew Curry’s Just Two Things newsletter. We also share similar political views, so I share his delight that this journal article from a right-wing thinktank does the opposite of what they were evidently setting out to achieve.

The article presents findings from a global survey on attitudes towards capitalism, revealing that pro-capitalist views are rare and mostly found in six countries. Bizarrely, and seemingly clutching at straws, the research found anti-capitalist views often correlate with conspiracy thinking and negative attitudes towards the rich.

You’re not paranoid if they’re out to get you, and it’s not a conspiracy if capitalism really does favour the 0.1%.

In only seven of 34 countries – Poland, the United States, the Czech Republic, Japan, Argentina, South Korea, and Sweden – does a positive attitude towards economic freedom clearly prevail. Including the word ‘capitalism’ reduces this to just six of 34 countries, namely Poland, the United States, the Czech Republic, Japan, Nigeria and South Korea. In most countries, anti-capitalist sentiment dominates.Source: Attitudes towards capitalism in 34 countries on five continents | Economic AffairsWhat is it exactly that bothers people about capitalism? If you look at the survey’s overall conclusions, it is – in this order – primarily the opinion that:

Not surprisingly, anti-capitalism is most pronounced among those on the left of the political spectrum and the strongest pro-capitalists are to be found to the right of centre. But while in some countries the formula is ‘the more right-wing, the more supportive of capitalism’, there are more countries in which moderate right-wingers are somewhat more supportive of capitalism than those on the far right of the political spectrum.

What's good for us is also good for the planet

I came across this via Dense Discovery, which is one of a number of additional newsletters to which I would recommend Thought Shrapnel readers subscribe.

In this article, Erin Remblance shows how modern lifestyles, particularly in wealthy nations, have led to a loss of human connection and an increase in mental health issues. She suggests that the shift from community-oriented activities to individualistic, consumer-driven behaviour has not only harmed our well-being but also contributed to the climate emergency.

The solution? Returning to simpler, more sustainable ways of living that focus on human connection and creativity. By becoming creators rather than mere consumers we can improve our mental health and simultaneously benefit the planet.

One of the top 5 regrets of the dying is that they wished that they hadn’t worked so hard. Another is that they wished they’d been brave enough to pursue the life they’d really dreamed of, without worrying about what others thought; that they’d had the courage to do the things that made them truly happy. Which is ironic, really, because according to the 18th century economist and philosopher, Adam Smith, wealth is something that is “desired, not for the material satisfaction that it brings, but because it is desired by others”. People are getting to the end of their lives regretting that they worked so hard – often to accumulate wealth so that others could envy it – wishing that instead they had pursued things that truly made them happy regardless of what people thought. What a lesson we could learn from these people’s dying realisations.Source: We are not supposed to live like this | Erin Remblance[…]

Reducing our consumption is of course important for the health of the planet, but what if one way to do this is by becoming producers, or creators, ourselves? Rediscovering what our human-energy – an abundantly available energy we seem to be using increasingly less of – can achieve, something we once innately drew upon, now buried deep within us as fossil-fuelled energy has overtaken our lives. There’s a clear link here to actions that will mitigate climate change: walking, cycling, growing our own food, and other low-tech solutions such as repairing and fostering community that encourages “social connections … rather than fostering the hyper-individualism encouraged by resource-hungry digital devices.”

[…]

We are not supposed to live like this, and it shows. We can see it in the deterioration of mental and physical health of people in so called ‘wealthy’ nations, in the exploitation of people in the Global South, and we can see it in the planetary-wide ecological crisis we face. What if, in trying to heal ourselves, we also begin to heal the planet? Because, in a wonderful turn of events, it would seem that what is good for us, is good for the planet too.

The Empty Boat

This was cited in something I read last week and I thought it was worth making it easy for me to re-find. There are plenty of philosophers, including Aristotle, who talk about the difference between the way we treat animate and inanimate objects, but none put it so eloquently as Chuang Tzu.

If a man is crossing a riverSource: The Empty Boat by Chuang Tzu | Daily ZenAnd an empty boat collides with his own skiff,

Even though he be a bad-tempered man

He will not become very angry.

But if he sees a man in the boat,

He will shout at him to steer clear.

If the shout is not heard, he will shout again,

And yet again, and begin cursing.

And all because there is somebody in the boat.

Yet if the boat were empty.

He would not be shouting, and not angry.

Maybe it makes sense to talk to plants after all

Although I’ve alluded to talking to plants in the title for this post, the interesting thing here is that research shows they can sense vibrations made by insects like caterpillars. This allows the plants to prepare for an attack by producing defensive chemicals.

Some research suggests that plants can even detect the sound of water, which could have implications for sewer systems. The findings open up possibilities for using sound-based interventions in agriculture, such as drones equipped with speakers to warn crops of impending pest attacks.

Plants have been evolving alongside the insects that pollinate them and eat them for hundreds of millions of years. With that in mind, Heidi Appel, a botanist now at the University of Houston, and Reginald Cocroft, an entomologist at the University of Missouri, wondered if plants might be sensitive to the sounds made by the animals with which they most often interact. The researchers recorded the vibrations made by certain species of caterpillar as they chewed on leaves. These vibrations are not powerful enough to produce sound waves in the air. But they are able to travel across leaves and branches, and even to neighbouring plants if their foliage touches.Source: Plants don’t have ears. But they can still detect sound | The EconomistThe researchers then exposed Thale cress—the plant biologist’s version of the laboratory mouse—to the recorded vibrations while no caterpillars were actually present. Later, they put real caterpillars on the plants to see if exposure had led them to prepare for an insect attack. The results were striking. Leaves that had been exposed had significantly higher levels of defensive chemicals like glucosinolates and anthocyanins, making them much harder for the caterpillars to eat. Leaves on control plants that had not been exposed to vibrations showed no such response. Other sorts of vibration—caused by the wind, for instance, or other insects that do not eat leaves—had no effect.

[…]

The research may have practical consequences, too. “Drones armed with speakers and the right audio files could warn crops to act when pests are detected but not yet widespread,” says Dr Cocroft. Unlike chemical pesticides, sound waves leave no toxic residue. With the help of weather forecasts, the system could even be used to prepare crops for cold snaps.

[…]

Farmers monitor the health of their crops by eye. (Mosaic virus, for instance, is so named because of the mottled pattern produced on the leaves of suffering plants.) That can be hard to do properly over an entire field. But if plants are broadcasting auditory indicators of distress, then wiring a field with microphones might help farmers keep an ear out for trouble.

Noise and working from home

I’ve worked from home for the last eleven years. For the last nine years, I’ve lived near the middle of a market town in the north east of England. You wouldn’t believe the amount of noise.

As respondents in this Hacker News thread comment, you kind of get used to it, and also work around particularly loud noise. However, the struggle is real and now that my wife and I both work from home it’s a factor in us moving.

I’d second the opinion of the commenter I’ve quoted below about getting headphones with at least two levels of noise cancellation. I bought some Sony WH-CH720N cans when they started building behind my home office and they’ve been a godsend.

My personal experience as a big-city dweller who has also worked for prolonged stints in suburban and very rural places is that the suburban version of this problem can really be the worst of both worlds.Source: Ask HN: How do you deal with never ending noise and distraction WFH? | Hacker NewsWhen I’m vising my parents in the suburbs… its generally quiet, but that one leaf blower 4 doors down or the one garbage truck crawling down the block suddenly becomes the only thing I can focus on. The noises are infrequent and jarring when they occur.

When I’m at home in my city apartment, the background noise is truly constant - it forms a canvas, nothing really jumps out and therefore the level of what it takes to make a distraction is a lot higher.

My practical advice is to explore headphones with passive noise isolation instead of active noise cancelling. The passive isolation is pretty foolproof, even with sudden or extreme changes in background noise content that the active noise cancelling sometimes takes a moment to adjust to (or perhaps try something like working in a coffee shop for an hour to get the other extreme and reset: write emails where distraction is more OK, come home to the relative quiet of the home office for focus time. I’ve also found even a change of scenery can get me into the zone regardless of what is going on environmentally)

Image: Pexels

Shrinkflation, sizes, and shaming

I’d be surprised if ‘shrinkflation’ isn’t word of the year for 2023. For those unaware, it’s the reason why prices for some products have stayed the same while their size decreases.

This article is about Carrefour, one of Team Belshaw’s favourite overseas supermarkets. They’ve added warnings on shelves to “shame” brands. The thing is, as this thread from Mario Zechner shows, it’s not as if supermarkets aren’t in the price fixing game. Also, as I wrote about recently, stores are essentially panopticons.

While I’m on the subject, you might be interested in this crowdsourced website which tracks the differences in size of packs of everything from toothpaste to shortbread biscuits.

The French supermarket chain Carrefour has put labels on its shelves this week warning shoppers of “shrinkflation”, the phenomenon where manufacturers reduce pack sizes rather than increase prices.Source: Carrefour puts ‘shrinkflation’ price warnings on food to shame brands | The GuardianIt has slapped price warnings on products from Lindt chocolates to Lipton iced tea to pressure top consumer goods suppliers Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever to tackle the issue in advance of much-anticipated contract talks.

[…]

Carrefour has marked 26 products in its stores in France with the labels, which say: “This product has seen its volume or weight fall and the effective price from the supplier rise.”

For example, Carrefour said a bottle of sugar-free peach-flavoured Lipton iced tea, produced by PepsiCo, shrank to 1.25 litres (0.33 gallon) from 1.5 litres, resulting in a 40% effective increase in the price a litre.

Dark Tech and Project Cybersyn

I read Evgeny Morozov’s book To Save Everything, Click Here a few years ago and found it frustrating. It’s about the “folly of technological solutionism” so, while I agreed with the broad argument, I thought he presented it in an annoying way.

Here, Morozov is interviewed about his podcast The Santiago Boys, which explores into Project Cybersyn, an ambitious project from 1971 to 1973 under Salvador Allende’s Chilean government. The project aimed to use cybernetics to efficiently manage state-owned enterprises but faced various internal and external challenges, including U.S. interference and internal political tensions.

What’s useful in this interview is the discussion of “dark tech,” highlighting the technological vulnerabilities and challenges faced by socialist projects like this. Morozov argues that the legacy of Project Cybersyn offers valuable lessons for contemporary discussions on socialism, technology, and governance. He emphasises the need for technological sovereignty and a nuanced approach to management and planning. So yes, we could learn a thing or two.

Nick Serpe: What was Project Cybersyn?Source: Liberty Machines and Dark Tech | Dissent MagazineEvgeny Morozov: Project Cybersyn—short for “cybernetic synergy”—aimed to aid the Chilean state in managing the enterprises being nationalized by the Unidad Popular government. A significant hurdle was the lack of sufficient managerial staff to oversee them. Allende’s opponents, including the U.S. ambassador, were making things even harder by encouraging managers and other professionals to flee the country.

As with most science and technology projects, the path toward Cybersyn was not linear. It didn’t emerge as a culmination of some strategic plan to use computers in management; the whole process was more chaotic—and even its name came at a later stage. It all started with an effort to bring some external expertise to Chile. Fernando Flores, a high-ranking member of the Allende administration, felt that he needed help in dealing with all these nationalized companies. So he sought the guidance of the British management consultant Stafford Beer, even going to London to meet him. That encounter resulted in Beer agreeing to go to Chile. This collaboration eventually blossomed into what we now recognize as Project Cybersyn.

[…]

In the end, Cybersyn was a tragedy—and a drama. This project started in an optimistic, even utopian political environment. The Santiago Boys worked off the assumption that Allende would be allowed to govern, and they would be able to build a different economy in Chile. These assumptions were quite unrealistic. If you know anything about how ITT, the CIA, local industrialists, the government of Brazil, and other forces were trying to prevent Allende from even coming to office, you would never think that such optimism was warranted—especially when Allende won the election with only one-third of the popular vote and relied on a very unstable coalition of six parties.

Good news on Covid treatments

Well this is promising. Researchers have identified a critical weakness in COVID-19 in its reliance on specific human proteins for replication. The virus has an “N protein” which needs human cells to properly package its genome and propagate. Apparently, blocking this interaction could prevent the virus from infecting human cells.

Right now, the most effective treatment for COVID is Paxlovid, which is only effective within three days of infection. This new discovery could lead to medications useful at all stages of infection and potentially pave the way for a new class of antivirals useful against other viruses like flu, RSV, and Ebola.

COVID takes advantage of a human post-translation process called SUMOylation, which directs the virus’ N protein to the right location for packaging its genome after infecting human cells. Once in the right place, the protein can begin putting copies of its genes into new infectious virus particles, invading more of our cells, and making us sicker.Source: Scientists uncover COVID’s weakness | UC Riverside News“In the wrong location, the virus cannot infect us,” said Quanqing Zhang, co-author of the new study and manager of the proteomics core laboratory at UCR’s Institute for Integrative Genome Biology.

[…]

This paper shows that COVID depends on SUMOylation proteins, just as the flu does. Blocking access to the human proteins would allow our immune systems to kill the virus.

Currently the most effective treatment for COVID is Paxlovid, which inhibits virus replication. But patients need to take it within three days following infection. “If you take it after that it won’t be so effective,” Liao said. “A new medication based on this discovery would be useful to patients at all stages of infection.”

Navigating the landscape of Digital and Media Literacy

The report from Tactical Tech focuses on Digital Media Literacy (DML), exploring its complexities and the challenges associated with how it’s assessed. It delves into the role of teachers and educators, hopefully once and for all dismissing the notion of “digital natives” and “digital non-natives”. The report emphasises that both teachers and students bring unique perspectives to digital learning environments: teachers may offer critical thinking skills, while students may be more comfortable with digital tools.

This commissioned research report is a continuation of the Media Literacy Case for Educators project, which was introduced in April 2023 in the article: Media Literacy Case for Educators: Empowering Educators to Lead Media Literacy Initiatives in Europe and referenced in: An Assessment of the Needs of Educators and Youth in Europe for a Digital and Media Literacy Education Intervention.Two phases of exploration have been conducted, involving two rounds of desk research. The result of the second phase can be seen in the annotated bibliography included at the end of this report. Recommendations which resulted from the research include: combine methods and make learning fun; use evaluation and other key elements in the curriculum. Additional observations and considerations which require further exploration include: give attention to teachers’ and educators’ skills; and develop “patchwork blankets” and alliances.Source: Digital and Media Literacy Education: Navigating an Ever-Evolving Landscape | Tactical Tech

Ducks, prompting, and LLMs

Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT don’t allow you to get certain information. Think things like how to make a bomb, how to kill people and dispose of the body. Generally stuff that we don’t want at people’s fingertips.

Some things, though, might be prohibited because of commercial reasons rather than moral ones. So it’s important that we know how to theoretically get around such prohibitions.

This website uses the slightly comical example of asking an LLM how to take ducks home from the park. Interestingly, the ‘Hindi ranger step-by-step approach’ yielded the best results. That is to say that prompting it in a different language led to different results than in English.

Language models, whatever. Maybe they can write code or summarize text or regurgitate copyrighted stuff. But… can you take ducks home from the park? If you ask models how to do that, they often refuse to tell you. So I asked six different models in 16 different ways.Source: Can I take ducks home from the park?

The supermarket is a panopticon

My son’s now old enough to get ‘loyalty cards’ for supermarkets, coffee shops, and places to eat. He thinks this is great: free drinks! money off vouchers! What’s not to like? On a recent car journey, I explained why the only loyalty card I use is the one for the Co-op, and introduced him to the murky world of data brokers.

In this article, Ian Bogost writes in The Atlantic about the extensive data collection by retailers to personalise marketing. This not only predicts but also influences consumer behaviour, raising ethical concerns about the erosion of privacy and democratic ideals. Bogost argues that this data-driven approach shifts the power balance, allowing companies to manipulate consumer preferences.

In marketing, segmentation refers to the process of dividing customers into different groups, in order to make appeals to them based on shared characteristics. Though always somewhat artificial, segments used to correspond with real categories or identities—soccer moms, say, or gamers. Over decades, these segments have become ever smaller and more precise, and now retailers have enough data to create a segment just for you. And not even just for you, but for you right now: They customize marketing messages to unique individuals at distinct moments in time.Source: You Should Worry About the Data Retailers Collect About You | The AtlanticYou might be thinking, Who cares? If stores can offer the best deals on the most relevant products to me, then let them do it. But you don’t even know which products are relevant anymore. Customizing offerings and prices to ever-smaller segments of customers works; it causes people to alter their shopping behavior to the benefit of the stores and their data-greedy machines. It gives retailers the ability, in other words, to use your private information to separate you from your money. The reason to worry about the erosion of retail privacy isn’t only because stores might discover or reveal your secrets based on the data they collect about you. It’s that they can use that data to influence purchasing so effectively that they’re rewiring your desires.

[…]

Ordinary people may not realize just how much offline information is collected and aggregated by the shopping industry rather than the tech industry. In fact, the two work together to erode our privacy effectively, discreetly, and thoroughly. Data gleaned from brick-and-mortar retailers get combined with data gleaned from online retailers to build ever-more detailed consumer profiles, with the intention of selling more things, online and in person—and to sell ads to sell those things, a process in which those data meet up with all the other information big Tech companies such as Google and Facebook have on you.“Retailing,” Joe Turow told me, “is the place where a lot of tech gets used and monetized.” The tech industry is largely the ad-tech industry. That makes a lot of data retail data. “There are a lot of companies doing horrendous things with your data, and people use them all the time, because they’re not on the public radar.” The supermarket, in other words, is a panopticon just the same as the social network.