2022

- Individualist. The resource is owned by one stakeholder and doesn’t require cross-party coordination. Examples might include: tweets, blogposts, personal websites, likes and comments.

- Collectivist. The resource is owned by multiple stakeholders¹ and needs coordination between them. Examples might include: naming registries, package managers, cryptocurrency account balances, aggregated comment threads.

- Eudaimonia ("satisfaction")

- Askesis ("discipline")

- Autarkeia ("self-sufficiency")

- Kosmopolites ("cosmopolitanism")

- Material abundance

- Egalitarianism — broadly shared prosperity, relatively moderate status differences, and broad political participation

- Human agency — the ability of human effort to alter the conditions of the world

Individualism and collectivism in decentralised networks

I don’t agree with Paul Frazee’s point in this post about Twitter vs “p2p Twitters” (by which he means the Fediverse) but otherwise he makes good points about governance and what he calls “operational collectivism”.

There are two kinds of resources in a network:Source: Back to basics: What is the point of decentralization? | Paul FrazeeI start the conversation here because it sets the context for all decentralization: that we have mastered individualist operation and collectivist standardization but have failed at collectivist operation. The inability to collectively operate networks has created the conditions for large monopolies on the Internet.

[…]

Whoever operates a collective resource has the power to change its implementation. The reason we decentralize operation is to distribute that power of implementation. If the stakeholders have the power of implementation, they’re able to ensure the resource represents their interests.

[…]

What’s the point of decentralization? It’s to ensure that the stakeholders — the end users — are represented. Individualism enforces personal control, while decentralized collectivism produces an intransigent consensus. We limit collectivist systems because they’re powerful systems, and power must always be checked.

Web3 and Ed3 are both problematic

Web3 is being discussed as if it’s anything other than the financialisation of everything. This post about ‘Ed3’ really struggles to square that circle when it comes to education. There are so many issues with it that I don’t really know where to start.

The bit that really jumped out for me, though, given that I’ve spent a decade working on Open Badges is the bit on credentialing. The cat is out of the bag by this point, especially in the “only paying for what you need” language. The whole point of education is that you don’t know what kind of person you’ll be at the end of it.

Anything else is just training.

Imagine if universities were fractionalized and you could earn the micro-credentials that mattered most for your career, only paid for what you needed, and owned a life-long portfolio with those credentials that were interoperable across all institutes & industries?Source: From Web3 to Ed3 - Reimagining Education in a Decentralized Worl… — MirrorWeb3 will also enable the metaverse to take shape over the next few decades; a universe of many buildable worlds that operate on decentralized infrastructure. The metaverse will make it possible to do everything we can do in the real world but enhanced by digital experiences & possible in an entirely virtual world.

Is QWERTY a really bad keyboard layout?

I’ve been able to touch-type since I was about 12 years of age, thanks to Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing. Like most people, I use the QWERTY layout, but I’ve always been curious about other layouts.

Apparently, it’s a bit of a myth that QWERTY was designed to slow typists down in case the mechanical keys got stuck. In the last edition of the Ultimate Typing Championship, all but one of the 26 competitors used QWERTY (and the one using the Dvorak layout came 12th).

The main thing to consider, in my opinion, is comfort. I remember being shocked once when I bought a keyboard and it came with a large warning that the use of any keyboard and mouse can cause ‘serious’ injuries.

This article talks about RSI (Repetitive Strain Injury), CTS (Carpal Tunnel Syndrome) and CTP (Carpal Tunnel Pressure).

If keyboard use does carry the risk of developing RSI, what is it about the keyboard that’s bad? Is it the physical design, the key layout, hand/wrist posture, or something else? My impression is that key layout is a relatively small component here, for several reasons. The first is my own experience, according to which it’s much more important to use a split keyboard, say, than the appropriate layout if I want to avoid RSI flare-ups. The second is that CTS is largely caused by CTP, which in theory seems more impacted by physical design (chiefly whether a keyboard is split and/or tilted/tented) and less by finger stretching or the horizontal rotating we do with our hands to reach keys at the sides of the keyboard. The third is Carpalx’s model, which suggests that established alternatives like Dvorak and Colemak, while better on the whole, use the pinky more heavily than does QWERTY – maybe it is a little bit bad to reach for the outermost keys, but any layout will have some keys at the extremes, so perhaps the difference between layouts just isn’t that great.Source: How Bad Is QWERTY, Really? A Review of the Literature, such as It Is | Erich GrunewaldWhat about QWERTY specifically? I wasn’t really able to find any research on this. Maybe that’s because it’s very hard to design experiments to test it? You can’t just take a bunch of people and ask half of them to start using Dvorak, because there’s a significant learning curve involved. But you don’t want to find out if learning a new layout is good, you want to find out using it is good once you have learned it. There is no natural control group for these experiments, and no obvious placebo.

In sum, keyboard use in general does seem to cause RSI, but the risk seems fairly small. Bad key layouts may only be a minor part of the RSI risk, though QWERTY does seem worse than most alternatives, relatively speaking. The evidence here is weak and my confidence intervals are wide.

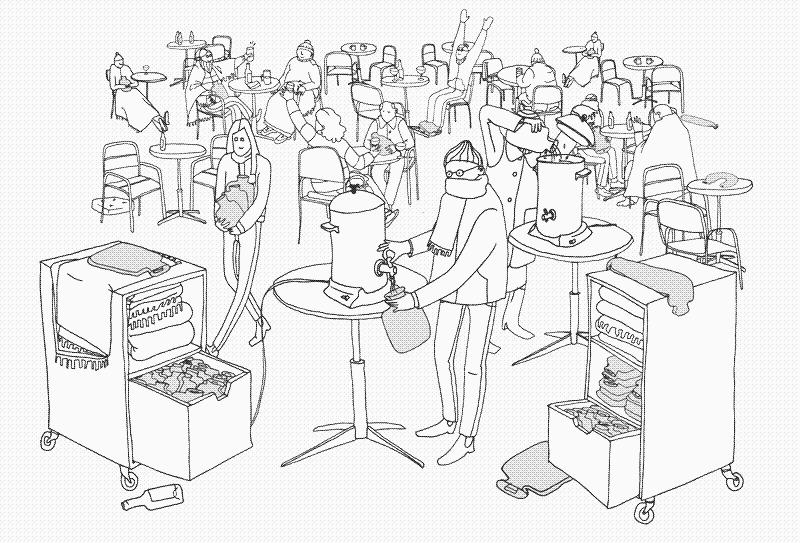

A low-tech solution for personal warmth

My family, especially the female members, have always been big fans of the hot water bottle. So much so, in fact, that one of my wife’s favourite presents was receiving a long snake-shaped hot water bottle that she can use in various configurations.

As we face a bit of an energy crisis, hot water bottles are definitely something more people should be using, as this article explains.

A hot water bottle is a sealable container filled with hot water, often enclosed in a textile cover, which is directly placed against a part of the body for thermal comfort. The hot water bottle is still a common household item in some places – such as the UK and Japan – but it is largely forgotten or disregarded in most of the industrialised world. If people know of it, they usually associate it with pain relief rather than thermal comfort, or they consider its use an outdated practice for the poor and the elderly.Source: The Revenge of the Hot Water Bottle | LOW←TECH MAGAZINEAs early as the 1500s, people started to use all kinds of portable containers filled with hot coals from the fire. These were used as foot warmers, hand warmers, and bed warmers. Most were made of metal, either brass or copper, and placed inside wooden or ceramic enclosures to prevent skin burns. Over time, hot coals were replaced by hot water, which is a cleaner and safer heat storage medium.

Initially, these first “real” hot water bottles were made from hard materials such as glass, metal, or stoneware. It was only with the invention of vulcanised rubber in the nineteenth century that more comfortable lightweight and flexible hot water bottles became an option. Spanish friends told me that hot water bottles used to be made from animal skins, but I could not verify this. It may well be true, because all over the world there’s a long tradition of using “water skins” for storing liquids.

Kids need life on the highest volume

This article is based on the author’s experiences as a teacher in state schools in the US. I should imagine the situation is exacerbated there, but it can’t be that great elsewhere, either.

My own kids seem like they’re OK. Our youngest, whose had Covid like me this week, has gone back to remote learning, which she enjoys as she completes her work quickly and then does other things. I think it’s particularly hard on teenagers, like our eldest, who are preparing for important exams.

The data about learning loss and the mental health crisis is devastating. Overlooked has been the deep shame young people feel: Our students were taught to think of their schools as hubs for infection and themselves as vectors of disease. This has fundamentally altered their understanding of themselves.Source: I’m a Public School Teacher. The Kids Aren’t Alright. | Common SenseWhen we finally got back into the classroom in September 2020, I was optimistic, even as we would go remote for weeks, sometimes months, whenever case numbers would rise. But things never returned to normal.

When we were physically in school, it felt like there was no longer life in the building. Maybe it was the masks that made it so no one wanted to engage in lessons, or even talk about how they spent their weekend. But it felt cold and soulless. My students weren’t allowed to gather in the halls or chat between classes. They still aren’t. Sporting events, clubs and graduation were all cancelled. These may sound like small things, but these losses were a huge deal to the students. These are rites of passages that can’t be made up.

[…]

They are anxious and depressed. Previously outgoing students are now terrified at the prospect of being singled out to stand in front of the class and speak. And many of my students seem to have found comfort behind their masks. They feel exposed when their peers can see their whole face.

[…]

At the beginning of the pandemic, adults shamed kids for wanting to play at the park or hang out with their friends. We kept hearing, “They’ll be fine. They’re resilient.” It’s true that humans, by nature, are very resilient. But they also break. And my students are breaking. Some have already broken.

When we look at the Covid-19 pandemic through the lens of history, I believe it will be clear that we betrayed our children. The risks of this pandemic were never to them, but they were forced to carry the burden of it. It’s enough. It’s time for a return to normal life and put an end to the bureaucratic policies that aren’t making society safer, but are sacrificing our children’s mental, emotional, and physical health.

Our children need life on the highest volume. And they need it now.

Paying for everything twice

As someone who’s recently started using a budgeting app, and who has a lot of music-making equipment lying around unused, I concur.

One financial lesson they should teach in school is that most of the things we buy have to be paid for twice.Source: Everything Must Be Paid for Twice | RaptitudeThere’s the first price, usually paid in dollars, just to gain possession of the desired thing, whatever it is: a book, a budgeting app, a unicycle, a bundle of kale.

But then, in order to make use of the thing, you must also pay a second price. This is the effort and initiative required to gain its benefits, and it can be much higher than the first price.

A new novel, for example, might require twenty dollars for its first price—and ten hours of dedicated reading time for its second. Only once the second price is being paid do you see any return on the first one. Paying only the first price is about the same as throwing money in the garbage.

Likewise, after buying the budgeting app, you have to set it all up, and learn to use it habitually before it actually improves your financial life. With the unicycle, you have to endure the presumably painful beginner phase before you can cruise down the street. The kale must be de-veined, chopped, steamed, and chewed before it gives you any nourishment.

If you look around your home, you might notice many possessions for which you’ve paid the first price but not the second. Unused memberships, unread books, unplayed games, unknitted yarns.

Ancient cynicism

As with stoicism, we’ve lost the ancient meaning of the word ‘cynicism’. I think you can probably tell a lot about how much love I have for Diogenes given that I named my phone after him (I name all my devices so I can easily identify them on wifi networks, etc.)

The original cynicism was a philosophical movement likely founded by Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, and popularized by Diogenes of Sinope around the fifth century B.C. It was based on a refusal to accept the assumptions and habits that discourage people from questioning conventional dogmas, and thus hold us back from the search for deep wisdom and happiness. Whereas a modern cynic might say, for instance, that the president is an idiot and thus his policies aren’t worth considering, the ancient cynic would examine each policy impartially.Source: We’ve Lost the True Meaning of Cynicism | The AtlanticThe modern cynic rejects things out of hand (“This is stupid”), while the ancient cynic simply withholds judgment (“This may be right or wrong”).

[…]

To pivot from the modern to the ancient, I recommend focusing each day on several original cynical concepts, none of which condemns the world but all of which lead us to question, and in many cases reject, worldly conventions and practices.

E2EE is for everyone

Not only has the current UK government underfunded the NHS since coming to power in an attempt to introduce market-based medicine, orchestrated the unprecedented national self-sabotage that is Brexit, and attacked the BBC, but they’re also trying to convince the British public that end-to-end encryption (E2EE) is only wanted by paedophiles.

The hypocrisy of it knows no bounds. These are the same politicians who rely on the E2EE of WhatsApp, Signal, and other messaging services to plot against one another and society in general.

Critics sometimes claim that encryption makes it impossible to subpoena or obtain a warrant for information from people’s phones — this is bizarre because governments already demand such data. What they are actually complaining about is that the “platform” — for instance Facebook — no longer wants to be able to see the content themselves. The warrant will have to be served upon the device owner, not upon the (social) network provider.Source: Why we need #EndToEndEncryption and why it’s essential for our safety, our children’s safety, and for everyone’s future #noplacetohide | dropsafeGood security demands that data that we share amongst family and friends should remain available only to those family and friends; and likewise that data which we share with businesses should remain only with those businesses, and should only be used for agreed business purposes.

Network providers — and, importantly, messaging-network and social-network providers — are helping their users obtain better data security by cutting themselves off from the ability to access plaintext content. Simply: they don’t need to see it, and it’s not their job to police or censor it. Their adoption of end-to-end encryption makes everyone’s data safer.

The world needs end-to-end encryption. It needs more of it. We need the privacy, agency, and control over data that end-to-end encryption enables. And encryption is needed everywhere and by everyone — not just by politicians and police forces.

The life-changing difference of an internet connection

As someone who’s seemingly around the same age as the author of this post, I agree that the internet has made my life better. I didn’t have it anywhere near as hard as them while growing up, but my online connections (and research) have certainly helped me escape into a different life.

This is part of the story of how the internet changed my life for the better. I’m an early millennial and I was raised online. Through the internet, I found friends, support, and the human connection that I was lacking in real life. I also found valuable information that helped me help myself and sometimes help others. The key with information is always to effectively filter the good from the bad, which is a genuine life skill unto itself. My life today isn’t perfect, but it’s better than it’s ever been. My message to all the people out there who are struggling is to believe in yourself. If you help yourself and you let others help you, things are never hopeless.Source: The Internet Changed My Life | Pointers Gone Wild

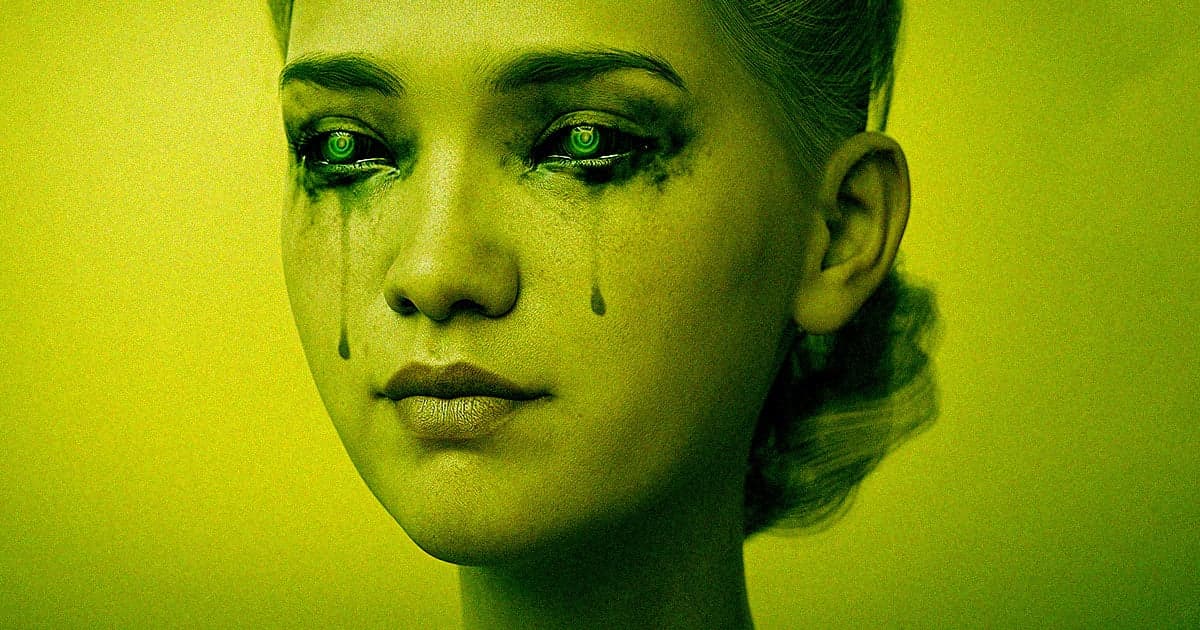

Abusing AI girlfriends

I don’t often share this kind of thing because I find it distressing. We shouldn’t be surprised, though, that the kind of people who physically, sexually, and emotionally abuse other humans beings also do so in virtual worlds, too.

In general, chatbot abuse is disconcerting, both for the people who experience distress from it and the people who carry it out. It’s also an increasingly pertinent ethical dilemma as relationships between humans and bots become more widespread — after all, most people have used a virtual assistant at least once.Source: Men Are Creating AI Girlfriends and Then Verbally Abusing Them | FuturismOn the one hand, users who flex their darkest impulses on chatbots could have those worst behaviors reinforced, building unhealthy habits for relationships with actual humans. On the other hand, being able to talk to or take one’s anger out on an unfeeling digital entity could be cathartic.

But it’s worth noting that chatbot abuse often has a gendered component. Although not exclusively, it seems that it’s often men creating a digital girlfriend, only to then punish her with words and simulated aggression. These users’ violence, even when carried out on a cluster of code, reflect the reality of domestic violence against women.

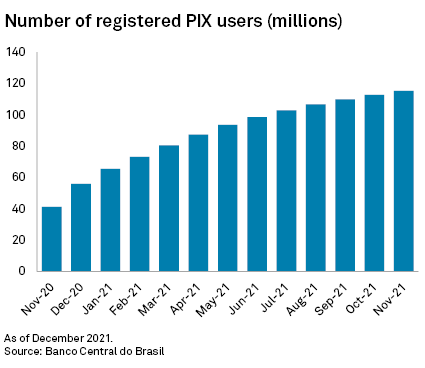

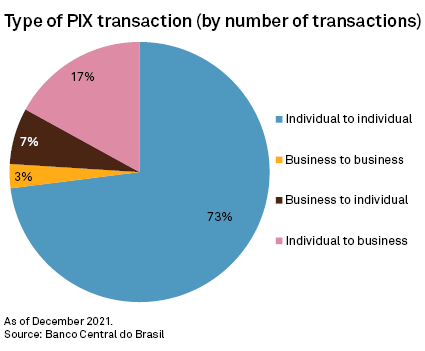

Pix and digital payments in Brazil

I came across this story via Benedict Evans' newsletter (it’s not the kind of thing I’d usually track). What I find interesting is this is a hugely successful rollout of a digital payments system done by a central bank. It’s helping real people, including those in poverty.

Meanwhile, crypto tokens are held by crypto bros and middle-class white guys like myself trying to make a quick buck. Just goes to show that innovation doesn’t always come from where you expect.

Source: Pix breaks ground in Brazil, shakes up payments market | S&P Global Market IntelligencePix, rolled out by the Banco Central do Brasil in Nov. 2020, was built for efficiency and financial inclusion. It now has 107.5 million registered accounts, more than half of the country’s population. One year after implementation, more than half a trillion Brazilian reais were transacted through the low-cost payments system last month. According to central bank data, Pix payments volume is already equivalent to 80% of debit and credit card transactions.

[…]

“Except for very particular transactions, market penetration tends to 99% on all individual transfers,” [Julian Colombo, CEO of banking technology firm N5] added. However, the rollout has not been without hiccups, including kidnapping.

[…]

On a recent Sunday in Rio de Janeiro, a three-member samba band played for a crowded restaurant. At the end, they passed around the tambourine to collect money. One diner apologized, saying he did not have any cash on him. The drummer said, “No problem, I take Pix,” and proceeded to share his code — which can be an email, phone number or other easy-to-remember code — with the diner, who promptly transferred the money his way.

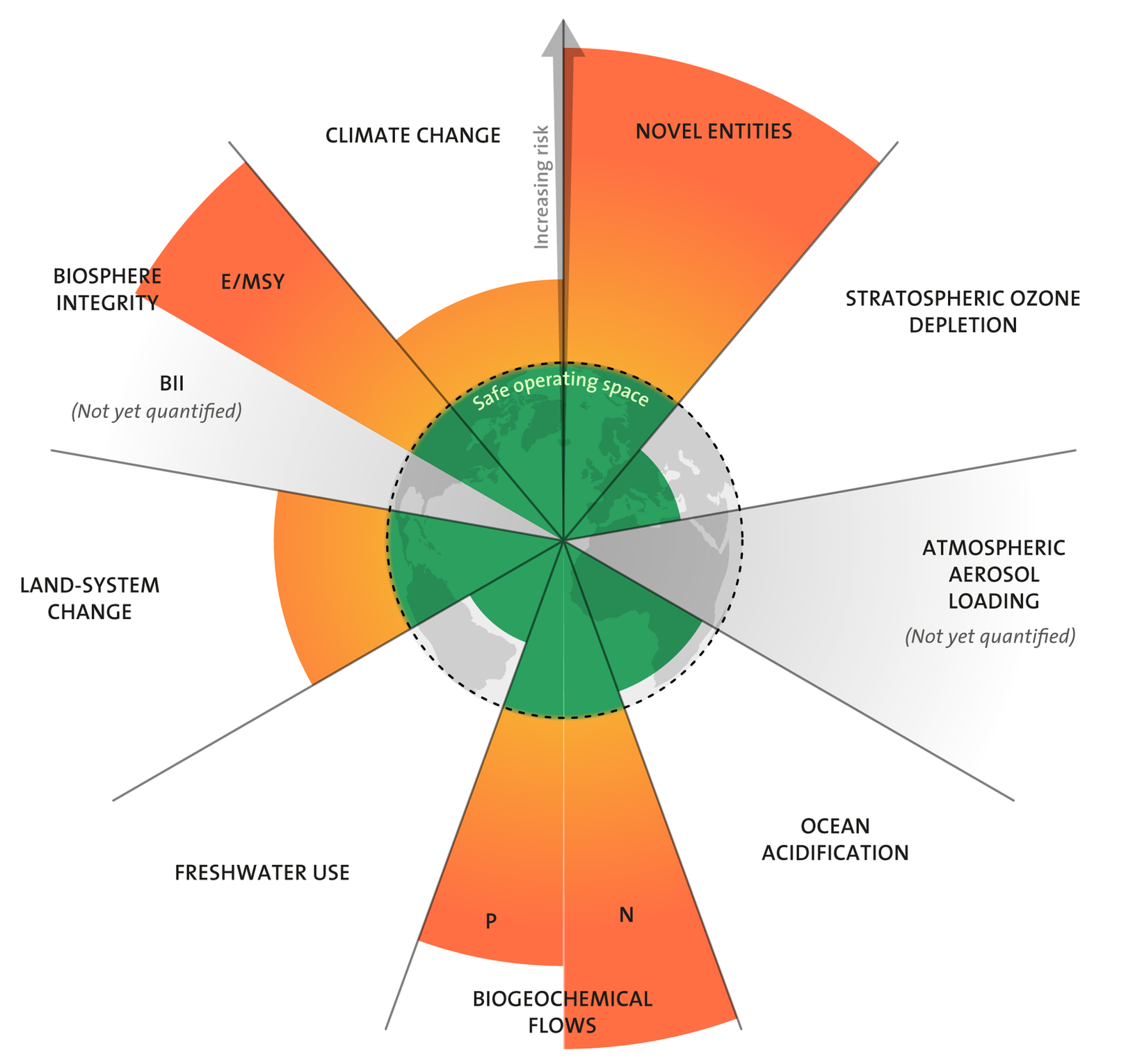

Nine planetary boundaries

This is a useful diagram to share in order to demonstrate that we might think we’re shafted with regards to climate change, but that pales into insignificance compared to pollution from chemicals and plastics.

The researchers say there are many ways that chemicals and plastics have negative effects on planetary health, from mining, fracking and drilling to extract raw materials to production and waste management.Source: Safe planetary boundary for pollutants, including plastics, exceeded, say researchers | Stockholm Resilience Centre“Some of these pollutants can be found globally, from the Arctic to Antarctica, and can be extremely persistent. We have overwhelming evidence of negative impacts on Earth systems, including biodiversity and biogeochemical cycles,” says Carney Almroth.

Global production and consumption of novel entities is set to continue to grow. The total mass of plastics on the planet is now over twice the mass of all living mammals, and roughly 80% of all plastics ever produced remain in the environment.

Plastics contain over 10,000 other chemicals, so their environmental degradation creates new combinations of materials – and unprecedented environmental hazards. Production of plastics is set to increase and predictions indicate that the release of plastic pollution to the environment will rise too, despite huge efforts in many countries to reduce waste.

Optimism about the future

I don’t have a particularly strong interest in sci-fi, nor do I have access to all of this paywalled post. However, I don’t need either to share a couple of insights.

First, I agree that the utopia/dystopia distinction are two sides of the same coin depending on what your view of what constitutes a flourishing human life. You don’t need to look far in our current situation to see that in action.

Second, while I’d probably broadly agree with the three conditions for optimism the author lays out, you could technically argue against all of them.

One possibility is that utopia and dystopia are just whatever the author decides to present as such. Take a war-torn unequal Malthusian future and add some soaring music and graphics of cities lighting up, and maybe audiences will see it as utopian. Or take a serene, pastel-colored post-scarcity hippie society and add a shirtless Sean Connery shouting that it’s all an illusion, and maybe it starts to seem like a creepy dystopia. (Of course, if this is what’s going on, there will be a tendency toward presenting any future as dystopian, since stories need external conflict; the world has to be “messed up” in some way in order for the protagonists to “fix” it.)Source: What makes an "optimistic" vision of the future? | NoahpinionBut in fact I submit that in order to be truly optimistic, a sci-fi world needs more than just a stirring theme song. It needs to present a future with several concrete features corresponding to the type of future people want to imagine actually living in. The “Wang Standard” is a good start, with its emphasis on the power of human effort, but in the end it relies on the somewhat circular notion of a “radically better” future. What does it mean for the future to be better? I submit that for a future to feel optimistic, it should feature the following elements:

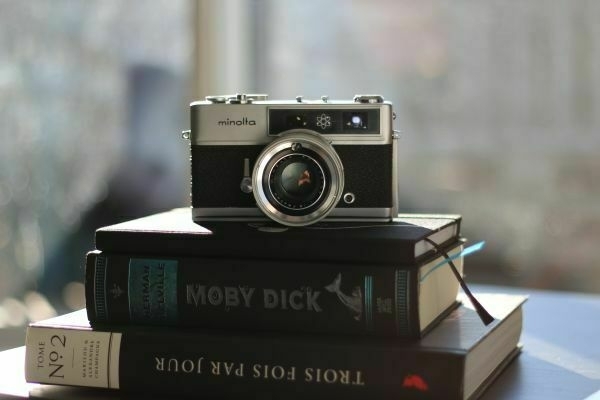

Reading is useless

I like this post by graduate student Beck Tench. Reading is useless, she says, in the same way that meditation is useless. It’s for its own sake, not for something else.

When I titled this post “reading is useless,” I was referring to a Zen saying that goes, “Meditation is useless.” It means that you meditate to meditate, not to use it for something. And like the saying, I’m being provocative. Of course reading is not useless. We read in useful ways all the time and for good reason. Reading expands our horizons, it helps us understand things, it complicates, it validates, it clarifies. There’s nothing wrong with reading (or meditating for that matter) with a goal in mind, but maybe there is something wrong if we feel we can’t read unless it’s good for something.Source: Reading is Useless: A 10-Week Experiment in Contemplative Reading | Beck TenchThis quarter’s experiment was an effort to allow myself space to “read to read,” nothing more and certainly nothing less. With more time and fewer expectations, I realized that so much happens while I read, the most important of which are the moments and hours of my life. I am smelling, hearing, seeing, feeling, even tasting. What I read takes up place in my thoughts, yes, and also in my heart and bones. My body, which includes my brain, reads along with me and holds the ideas I encounter.

This suggests to me that reading isn’t just about knowing in an intellectual way, it’s also about holding what I read. The things I read this quarter were held by my body, my dreams, my conversations with others, my drawings and journal entries. I mean holding in an active way, like holding something in your hands in front of you. It takes endurance and patience to actively hold something for very long. As scholars, we need to cultivate patience and endurance for what we read. We need to hold it without doing something with it right away, without having to know.

The cost of a thing is the amount of life which is required to be exchanged for it

This article in The Atlantic by Alan Lightman points out how biophilic we have been historically as a species, and how that’s changed only recently.

None of this, of course, helps with the climate emergency and the concomitant biodiversity collapse. I read the WEF Global Risks Report for 2022 and, well, I’ve read more hopeful documents.

Most of the minutes and hours of each day we spend in temperature-controlled structures of wood, concrete, and steel. With all of its success, our technology has greatly diminished our direct experience with nature. We live mediated lives. We have created a natureless world.Source: This Is No Way to Be Human - The AtlanticIt was not always this way. For more than 99 percent of our history as humans, we lived close to nature. We lived in the open. The first house with a roof appeared only 5,000 years ago. Television less than a century ago. Internet-connected phones only about 30 years ago. Over the large majority of our 2-million-year evolutionary history, Darwinian forces molded our brains to find kinship with nature, what the biologist E. O. Wilson called “biophilia.” That kinship had survival benefit. Habitat selection, foraging for food, reading the signs of upcoming storms all would have favored a deep affinity with nature. Social psychologists have documented that such sensitivities are still present in our psyches today. Further psychological and physiological studies have shown that more time spent in nature increases happiness and well-being; less time increases stress and anxiety. Thus, there is a profound disconnect between the natureless environment we have created and the “natural” affections of our minds. In effect, we live in two worlds: a world in close contact with nature, buried deep in our ancestral brains, and a natureless world of the digital screen and constructed environment, fashioned from our technology and intellectual achievements. We are at war with our ancestral selves. The cost of this war is only now becoming apparent.

[…]

I am not so naive as to think that the careening technologization of the modern world will stop or even slow down. But I do think that we need to be more mindful of what this technology has cost us and the vital importance of direct experiences with nature. And by “cost,” I mean what Henry David Thoreau meant in Walden: “The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” The new technology in Thoreau’s day was the railroad, which he feared was overtaking life. Thoreau’s concern was updated by the literary critic and historian of technology Leo Marx in his 1964 book, The Machine in the Garden. That book describes the way in which pastoral life in America was interrupted by the technology and industrialization of the 19th and 20th centuries. Marx could not have imagined the internet and the smartphone, which arrived only a few decades later. And now I worry about the promise of an all-encompassing virtual world called the “metaverse,” and the Silicon Valley arms race to build it. Again, it is not the technology itself that should concern us. It is how we use that technology, in balance with the rest of our lives.

Matching work activities to mind modes

This by Jakob Greenfeld reminds me of Buster Benson’s evergreen post Live like a hydra — especially the sub-section ‘Seven modes (for seven heads)’.

Of course, you can’t always be driven by what mood you happen to be in. Sometimes, you have to change things up to ensure that your mood changes. But hey, all bets are off during a pandemic, right?

I recently discovered a simple step-by-step process that significantly increased my personal productivity and made me happier along the way.Source: Effortless personal productivity (or how I learned to love my monkey mind) – Jakob GreenfeldIt costs $0 and no, it’s not some note-taking or to-do list system.

In short:

Step 1: develop meta-awareness of your state of mind.

Step 2: pattern-match to identify your mind’s most common modes.

Step 3: learn to pick activities that match each mode.

Does Not Translate

I enjoyed some of these untranslatable words from languages other than English.

Sturmfrei (German) When all the people you live with are gone for a while and you have the whole place to yourself.Source: Does Not Translate – Words that don’t translate to other languagesGyakugire (Japanese) Getting mad at somebody because they got mad at you for something you did.

Bear favour (Swedish) To do something for someone with good intentions, but it actually has negative consequences instead.

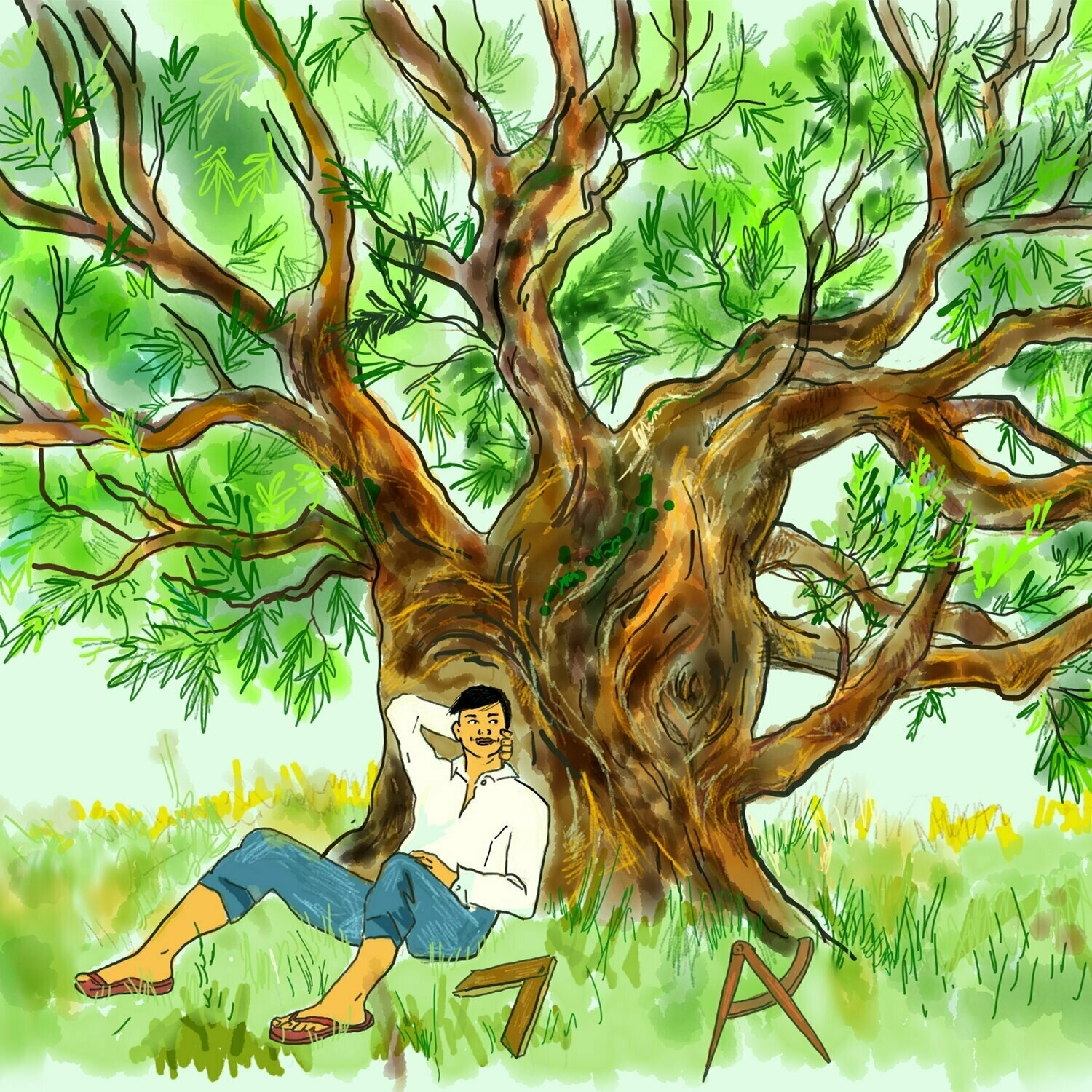

How to be useless

I love articles that give us a different lens for looking at the world, and this one certainly does that. It also provides links for further reading, which I very much appreciate.

Zhuangzi argued that we can reclaim our lives, and be happier and more fulfilled, if we become more useless. In this, he went against many influential thinkers of his time, such as the Mohists. These followers of Master Mo (c470-391 BCE) prized efficiency and welfare above all. They insisted on cutting away all ‘useless’ parts of life – art, luxury, ritual, culture, leisure, even the expression of emotions – and instead focused on ensuring that people across the social classes receive essential material resources. The Mohists viewed many practices common at the time as immorally wasteful. Rather than a funeral rich with rituals following tradition, such as burial within three layers of coffins and a years-long mourning period, Mohists recommended simply digging a pit deep enough so the body doesn’t smell. You were permitted to cry on your way to and from the burial site, but then you needed to return to work and life.Source: How to be useless | Psyche GuidesAlthough the Mohists wrote more than 2,000 years ago, their ideas sound familiar to modern ears. We frequently hear how we should avoid supposedly useless things, such as pursuing the arts, or a humanities education (see the all-too-frequent slashing of liberal arts budgets at universities). Or it’s often said that we should allow for these things only insofar as they benefit the economy or human welfare. You might have felt this discomfort in your own life: the pressure from the meritocracy to serve some purpose, have some benefit, maximise some utility – that everything you do should be, in some sense, useful.

However, as we will show here, Zhuangzi offers an essential antidote to this pernicious means-ends way of thinking. He demonstrates that you can improve your life if you let go of the anxiety of wanting to serve a purpose. To be sure, Zhuangzi doesn’t altogether spurn usefulness. Rather, he argues that usefulness itself should not be life’s bottom line.

Your accusations are your confessions

I didn’t know Stephen Downes had a political blog. These are his thoughts on cancel culture which, like most of what he says in general, I agree with.

Every time a conservative complains about censorship or ‘cancel culture’ we need to remind ourselves, and to say to them,Source: Cancelled | Leftish“You are the one complaining about cancel culture because you are the one who uses silencing and suppression as political tools to advance your own interests and maintain your own power.

“You are complaining about cancel culture because the people you have always silenced are beginning to have a voice, and they are beginning to say, we won’t be silent any more.

“And when you say the people working against racism and misogyny and oppression are silencing you, that tells us exactly who – and what – you are.”

“Your accusations are your confessions.”

Web3, the metaverse, and the DRM-isation of everything

I’ve been reading a report entitled Crypto Theses for 2022 recently. Despite having some small investments in crypto, the world that’s painted in that report is, quite frankly, dystopian.

The author of that report admits to being on the right of politics and, to my mind, this is the problem: we’ve got people who believe that societal control and monetisation of all of the things in a free market economy is desirable.

This article focuses on Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement at the end of 2021 about the ‘metaverse’. This is something which is a goal of the awkwardly-titled ‘web3’ movement.

Perhaps I’m getting old, but to me technology should be about enabling humans to do new things or existing things better. As far as I can see, crypto/web3 just adds a DRM and monetisation layer on top of the open web?

In one sense, it's a vision of a future world that takes many long-existing concepts, like shared online worlds and digital avatars, and combines them with recently emerging trends, like digital art ownership through NFT technology and digital "tipping" for creators.Source: Zuckerberg Convinced the Tech World That ‘the Metaverse’ Is the Future | Business InsiderIn another sense, it’s a vision that takes our existing reality — where you can already hang out in 2D or 3D virtual chat rooms with friends who are or are not using VR headsets — and tacks on more opportunities for monetization and advertising.