Enough is enough

Today, the pedo-authoritarian US and genocidal Israel attacked Iran to distract from respective domestic problems. At the time of writing, reports are that 85 people have died after strikes hit a girls school.

So, to put that in perspective, innocent girls have died in attempt to cover up a president’s obvious involvement in a sex trafficking ring, and another leader’s issues caused by starving a neighbouring country to death.

Source: Bluesky

Super Mario World Map

I don’t know the original source of this, but I think it’s quite old. A reverse image search led to 118 pages of results…

Source: Klaus Zimmerman

WAO is closing

I know some people only read Thought Shrapnel and not the rest of my work, so I’m just going to give a quick update to say that the co-op I helped set up 10 years ago, and which has been a source of creative and collaborative inspiration, will be closing on 1st May 2026.

We’re all still friends. I’m going to be working through my consultancy business, Dynamic Skillset so get in touch if I can help you or your organisation!

After ten years of creative cooperation, we’re announcing that We Are Open Co-op (WAO) will close its doors on our 10th birthday: 1st May 2026. This has been a carefully considered, collaborative decision — the kind we’ve always tried to model as a co-op.

But, as you can imagine, we’re a bit emotional about it, and it also feels a bit weird to finally say it out loud and in public.

WAO is a strong, well-respected brand. We continue to have wonderful clients, meaningful work and good relationships with each other. People are finally waking up to the idea that flat hierarchies and consent-driven businesses are the future.

In some ways, this is a continuation rather than an ending, as we’ll be carrying forward the cooperative principles we’ve practised into new systems and relationships.

Source: WAO blog

Image: CC BY-ND Visual Thinkery for WAO

Agentic commerce is a catastrophe for every business whose moat is made of friction

I’m too young for memories of the original game on the Commodore 64, but I do remember the SEGA Master System version of Spy vs. Spy. While I wasn’t allowed to have a console myself, I would play on friends' devices. The thing I really remember, though, is my parents leaving me to play for a while which was on a demo unit in Fenwick’s toy department in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. It was a game in which you, as either the ‘black’ or ‘white’ spy had to outwit the other spy.

This homely introduction serves to explain the graphic accompanying both this post and the one I’ve take it from — an extremely clear-eyed view of what “agentic commerce” means for brands. Usually, this kind of thing wouldn’t interest me, but I do like clear thinking on things orthogonal to my line of work.

Let’s start with the setup, which involves a post on an influential blog which was more “speculative fiction” than “investor advice”:

For context: Citrini Research is a financial analysis firm focused on thematic investing research with a highly influential Substack. The piece in question, published this past Sunday, is a fictional macro memo written from June 2028, narrating the fallout of what they call the “human intelligence displacement spiral” – a negative feedback loop in which AI capabilities improve rapidly, leading to mass white collar layoffs, spending decreases, margins tightening, companies buying more AI, accelerating the loop. It’s all a “scenario, not a prediction,” and not really all that new: the idea that a (unit of AI capex spend) < (unit of disposable income) circulating in the real economy has been doing the rounds for a while now. Yet Citrini caused a very real market selloff earlier this week. Apparently this scenario wasn’t priced in.

What the smart people at NEMESIS point out is that our current neoliberal version of capitalism in advanced service-based economies has “built a rent-extraction layer on top of human limitations” as “[m]ost people accept a bad price to avoid more clicks or cognitive labor [with] brand familiarity substituting for diligence.”

In Citrini’s scenario, AI agents dismantle this layer entirely. They price-match across platforms, re-shop insurance renewals, assemble travel itineraries, route around interchange fees etc. Agents don’t mind doing the things we find tedious.

Basically what Citrini is describing as the destruction of habitual intermediation is, from the POV of Nemesis HQ, a description of one of the primary economic functions of brands dissolving.

Essentially, brands “reduce the friction of decision-making” because it’s a shortcut to buying more of what you know you like. There’s a reason I’ve got three Patagonia hoodies, four Gant jumpers, and all of my t-shirts are from THG. But what happens when an agent which knows your preferences can go off and do your shopping for you? Book your holiday? Organise your insurance renewals?

In Citrini’s 2028 world of agentic commerce, brand loyalty is nothing but a tax. When given license to do so, the agent doesn’t care about your favorite app or branded commodity, feel the pull of a well-designed checkout UX flow or default to the app your thumb navigates to the easiest on your home screen. It evaluates every option on price, fit, speed, or whatever other parameters you’ve set. The entire edifice of brand preference built over decades of advertising, design and behavioral psychology becomes, from the agent’s perspective, noise.

Though its not a wholesale “end of brands” it is a catastrophe for every business whose moat is made of friction. And a remarkable number of moats are made pretty much of only friction (think: insurance, financial services, telecom, energy, SaaS, most platforms, Big Grocery, airlines, cars, etc.). Generally speaking, this is a good thing (creative destruction!), and frees the labor of large swaths of branding and marketing professionals to societally more useful ends.

What I think scares people is uncertainty. I probably have a higher tolerance for different forms of ambiguity than most people I know. Well, cognitively, at least; sometimes the body keeps the score.

Source & image: NEMESIS

Units of attention

Good stuff from Jay Springett, who also links to a 60-page PDF called Paying Attention that I… haven’t paid attention to (yet!)

The attention economy rewards the same behaviours regardless of whether the content being spread is a coordinated disinformation campaign or a genuinely interesting essay. The platform does not distinguish between the two. It just measures the engagement.

There is a practical implication buried somewhere in the above though I think.

That if the first units of attention are the ones that change behaviour most, then being liberal with the like button actually matters. dLeaving a comment, sharing a post, replying to something you found worthwhile are small acts that actually work. In the face of “the firehose” the modest counter-move is to be deliberate about where your attention goes, and cultivating the things that you want to see more of.

This is interesting when juxtaposed with something Nita Farahany says in the transcript of a conversation posted on The Exponential View:

This gets at a fundamental question about what it means to act autonomously. Are you acting in a way consistent with your own desires, or are you being steered by somebody else’s desires? There’s very little we do these days that is steered by our own desires.

I’m teaching a class this semester at Duke on mental privacy, advanced topics in AI law and policy. I ran an attention audit on my students. They recorded how many times they picked up their devices over three days, and what they spent their attention on. Day one: record it, don’t change your behaviour. Day two: no apps that algorithmically steer you — which meant basically nothing was allowed. Day three: do whatever you want, record it again. Day two was remarkable. Somebody read a book. They couldn’t remember the last time they’d done that. These are students. Someone finished a puzzle they’d been convinced they didn’t have time for. And day three? Worse than day one. Utterly sucked back in.

I was flicking back through my notebook, which I have not used enough in the last 18 months or so, and came across a note I’d made while reading Oliver Burkeman’s excellent book Four Thousand Weeks. He quotes Harry Frankfurt as saying that our devices distract us from more important matters — it’s as if we let what they show us define what counts as “important”. As such, our capacity to “want what we want to want” is sabotaged.

Sources:

Image: Marcus Spiske

👋 A reminder that I’ve been on holiday this week, so no Thought Shrapnel.

However, I’ve still been saving things to my Are.na channels if you’d like to peruse those…

– Doug

TechFreedom

As explained in this post, Tom Watson and I are putting together an offer to help organisations with their digital sovereignty.

Sign up if you’re interested in joining our first cohort. No obligation.

You cannot manage what you cannot see. Most organisations operate in a fog of invisible reliance; you rely on platforms that obscure their workings behind slick interfaces and terms you never read.

TechFreedom helps you clear the air. We give you the tools to look past Big Tech’s version of the Cloud and build a digital infrastructure that is open, visible, and under your control.

Source: techfreedom.eu

A range of authentic selves?

Jo Hutchinson reshared this on LinkedIn a few days ago, and I wanted to save/share my comments on it. The original post was by Tricia Riddell, a Professor of Applied Neuroscience and includes a short video. In it, she talks about there being “a range of authentic selves” that people can bring to a situation rather than a single “authentic self.”

Riddell wonders whether this is what leads to imposter syndrome, which is usually suffered by high-achievers. “You cannot feel like an imposter,” she says, “unless there is something you believe you’re failing to live up to.”

My response, because it’s easier for me to re-find things here rather than on social media:

As someone who suffers from imposter syndrome most days of my life, it resonates.

I am, though, reminded of something that John Bayley wrote in one of the biographies of his wife, the philosopher Iris Murdoch. He said that Iris believed that she “didn’t have a strong sense of self.” I’ve thought about this over two decades, and I think it maps onto what’s being discussed here.

On the one hand, you could say that those with a strong sense of self want to bring a single “authentic” self to every situation. Which, as Tricia Riddell points out, would mean that they’re not bringing other stories into the situation.

Or, on the other hand, you might say that those without a strong sense of self have a fragmented view of themselves. The imposter syndrome is the price that is paid for an integrated sense of self.

I haven’t figured it out yet, but I find the whole thing fascinating.

Source: LinkedIn

Image: Amy Vann

Each culture is made of shared framings—ontologies of things that are taken to exist

Most of this post talks about the differences between Japan and Italy, which makes it well worth reading in full. What I like about it, though, is that it goes beyond “mental models” to talk about framings and how these are the unseen, and somewhat hidden things that make cultures different. Fascinating.

A mental model is a simulation of “how things might unfold”, and we all build and rebuild hundreds of mental models every day. A framing, on the other hand, is “what things exist in the first place”, and it is much more stable and subtle. Every mental model is based on some framing, but we tend to be oblivious to which framing we’re using most of the time […].

Framings are the basis of how we think and what we are even able to perceive, and they’re the most consequential thing that spreads through a population in what we call “culture”.

[…]

Each culture is made of shared framings—ontologies of things that are taken to exist and play a role in mental models—that arose in those same arbitrary but self-reinforcing ways. Anthropologist Joseph Henrich, in The Secret of Our Success, brings up several studies demonstrating the cultural differences in framings.

He mentions studies that estimated the average IQ of Americans in the early 1800’s to have been around 70—not because they were dumber, but because their culture at the time was much poorer in sophisticated concepts. Their framings had fewer and less-defined moving parts, which translated into poorer mental models. Other studies found that children in Western countries are brought up with very general and abstract categories for animals, like “fish” and “bird”, while children in small-scale societies tend to think in terms of more specific categories, such as “robin” and “jaguar”, leading to different ways to understand and interface with the world.

But framings affect more than understanding. They influence how we take in the information from the world around us.

Source: Aether Mug

Image: Maksym Tymchyk

Like it or not, it is a basic fact of human cognition that we think and act politically as members of social groups.

This post on the blog of the American Philosophical Association (APA) talks about political epistemology. Samuel Bagg is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of South Carolina and argues that the reason presenting people with facts doesn’t change their political opinions is due to our social identities.

This resonates with me more than the usual framing where in which we’re told that we need to appeal to people’s emotions. Social identity makes much more sense, and so (as Bagg argues) the way out of this mess isn’t to “ensure every citizen employs optimal epistemic practices” but instead to strengthen our “broadly reliable collective practices.”

I’ve often said that one of the reasons for Brexit was the [attack on expertise by Michael Gove]9www.ft.com/content/3…). Attacking institutions which are proxies through which people can know and understand the world is corrosive, divisive, and ultimately, a cynically populist move.

On the individual level, we are right to worry about the epistemic impact of motivated reasoning, cognitive biases, and “political ignorance.” And at the systemic level, we are right to lament the rise of talk radio, cable news, social media, and the attention economy, along with the corresponding decline of local news, professional journalism, content standards, and so on. Trends in our political economy have indeed conspired with underlying human frailties to undermine the epistemic foundations of a stable and functioning democracy—even in its most minimal form.

Yet this diagnosis is also crucially incomplete, in ways that distort our search for solutions. When we understand the problem in epistemic terms, we naturally seek epistemic answers: better fact-checking, more deliberation, better education, greater media balance. We aim to develop the “civic” and “epistemic virtues” of unbiased, fair-minded citizens. And indeed, such projects are surely worth pursuing. The epistemic failures they aim to address have deeper roots in our political psychology, however—and overcoming them requires grappling with those roots more directly.

In short, decades of research have demonstrated that our political beliefs and behavior are thoroughly motivated and mediated by our social identities: i.e., the many cross-cutting social groupings we feel affinity with. And as long as we do not account for this profound and pervasive dependence, our attempts to address the epistemic failures threatening contemporary democracies will inevitably fall short. More than any particular institutional, technological, or educational reform, promoting a healthier democracy requires reshaping the social identity landscape that ultimately anchors other democratic pathologies.

[…]

We do not generally decide which groups to identify with on the basis of their epistemic credentials regarding political questions. And even if we were to use such a standard, our judgments about which groups satisfy it would be inescapably colored by our pre-existing identities, formed on other bases or inherited from childhood. Developing certain “epistemic virtues” may mitigate some of our blind spots, finally, but it is hubris to think anyone can escape such biases entirely. Like it or not, it is a basic fact of human cognition that we think and act politically as members of social groups.

[…]

The trouble is not that reliable collective truth-making practices no longer exist, but that significant portions of the population no longer trust them—and that as a result, the truths they establish no longer constrain those in power.

[…]

What best explains contemporary epistemic failures… is not the decay of individual epistemic virtues, but the growing chasm between reliable collective truth-making practices and the social identities embraced by large numbers of people. And as a result, the only feasible way out of the mess we are in is not to ensure every citizen employs optimal epistemic practices, but to weaken their social identification with cranks and conspiracy theorists, and strengthen their identification with the broadly reliable collective practices of science, scholarship, journalism, law, and so on. The most visible manifestations of the problem might be epistemic, in other words, but its roots lie in social identity. And the most promising solutions will therefore tackle those roots.

Source: Blog of the APA

Image: Steve Johnson

Digital sovereignty, French-style

In the wake of Big Tech propping up Trump’s increasingly authoritarian regime, European countries and organisations are taking seriously the issue of digital sovereignty.

This initiative from the French didn’t spring out of nowhere — their Open Source Docs offering was something I experimented with last year — but they’ve now got ‘La Suite’ which offers more. The site is, probably entirely intentionally only in French (of which I only have a schoolboy understanding) so I translated their About page.

It’s pretty awesome that they’re a co-op, that they see digital technology as political (which of course it is), and that they want to contribute to the digital commons 🤘

A political ambition

Digital technology is political. The choice of our creation and collaboration tools can either perpetuate the captive income of proprietary publishers or support open source alternatives that set us free. This choice comes at a price: most organisations do not have the means to design tailor-made tools or manage their own free software instances.

With LaSuite.coop, we are creating a modular offering to enable associations, cooperatives, social and solidarity economy enterprises, institutions and universities to equip themselves with the best open source solutions and be supported by dedicated teams. A world is dying, and this project is our contribution to the future that is being built thanks to the actions of all these organisations.

A model for contributing to the commons

To compete in the long term with proprietary software financed by venture capital and its quest for hegemony and profitability, we want every LaSuite.coop application to be based on a true digital commons. That is to say, free software developed, financed and governed in an open and transparent manner by a plurality of public and private actors. The Decidim project and the French government’s digital suite are among our main sources of inspiration.

With LaSuite.coop, we donate a portion of our revenue to the communities that maintain and develop the software we offer. In this way, we contribute directly to a virtuous and resilient circle of mutualisation and collective decision-making.

A cooperative venture

The organisations behind LaSuite.coop have been committed to promoting free and democratic digital technology since their inception. We pool our years of complementary experience in hosting, development, technical project management, training and strategic consulting.

Source: La Suite

How to Be Less Wrong in a Polycrisis

A rare cross-post for me from my Open Thinkering blog. I’m really rather pleased with this and would like you to read it.

Source: Open Thinkering

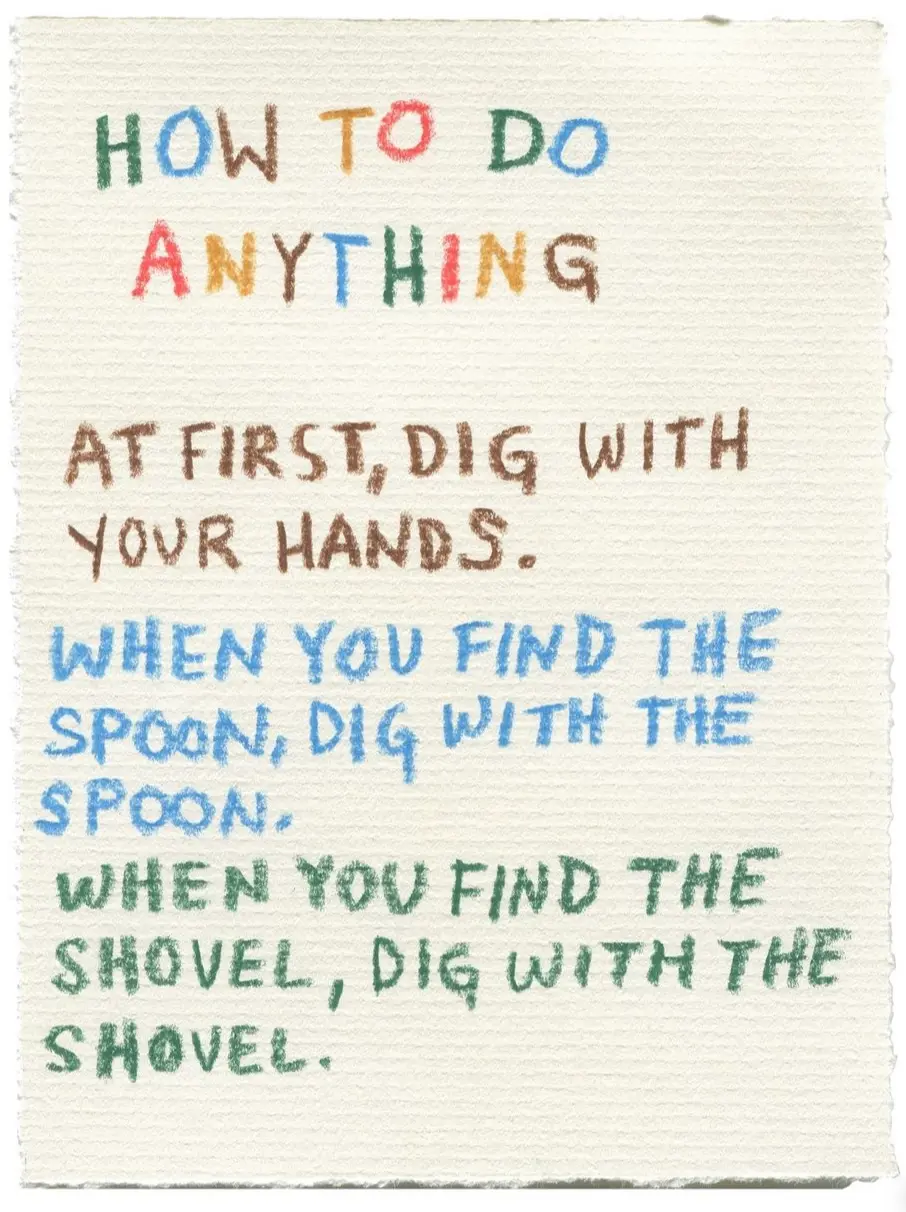

Hands, spoon, shovel

I’ve been using Claude Opus 4.6 over the last couple of weeks, and let me tell you: it feels like digging with a SHOVEL.

Source: Are.na

A rough attempt at laying out what in philosophy is most relevant for AI.

While I expected studying Philosophy as an undergraduate to be personally useful and indirectly useful to my professional career, I didn’t forsee how relevant it would be to our increasingly AI-infused world.

While I expected studying Philosophy as an undergraduate to be personally useful and indirectly useful to my professional career, I didn’t forsee how relevant it would be to our increasingly AI-infused world.

In this post, Matt Mandel, after “[coming] to realize that using LLMs is pushing all of us to more closely examine our philosophical assumptions” has sketched out “a rough attempt at laying out what in philosophy is most relevant for AI.”

I’ve taken the list — covering things with which I’m familiar and those things I’d like to follow-up on — and added links. The “What is agency?" section is particularly timely, as I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently but need to do more reading.

Part 1: Philosophical Concepts

What is a mind?

- Nagel, What is it like to be a bat

- Chalmers, Facing up to the problem of consciousness

- Putnam, The Nature of Mental States

- Searle, Minds, Brains, and Programs

What is agency?

- Anscombe, Intention

- Dennett, The Intentional Stance

- Bratman, Shared Cooperative Activity

- Applbaum, Legitimacy (group agents)

Who has moral status?

- Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals (indirect duties)

- Singer, Animal Liberation

- Korsgaard, Fellow Creatures

What are reasons and values?

- Hume, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

- Parfit, On What Matters (Volume II, Part 6)

- Mackie, Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong

- Korsgaard, The Sources of Normativity

Part 2: How should we build AI

How might AIs come to implement our values?

- Kripke, Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language

- Bostrom, The Superintelligent Will

- Plato, The Republic (Book I)

- Anthropic, Emergent Misalignment

How should AI be involved in governance?

- Applbaum, Legitimacy (“domination by a stone”)

- Séb Krier, Coasean Bargaining at Scale

- Newsom, Snell v United Specialty Insurance Company (concurrence)

- Cass Sunstein and Vermeule, Law and Leviathan

How might AI impact human flourishing?

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

- Mill, On Liberty

- Frankfurt, Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person

- Brendan McCord, Live by the Claude, Die by the Claude

How do we find meaning in a post-AGI world?

- Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

- Nozick, Philosophical Explanations (Philosophy and the Meaning of Life)

- Bostrom, Deep Utopia

- Mandel, The Top Three AGI-Proof Careers and What They Reveal About Our Humanity and The Future

In terms of Part 1, to the What is a mind? section it’s definitely worth adding Turing’s foundational paper from 1950 asking “can machines think?” It’s the one that introduces the “Turing test” and directly sets up the questions that Searle and Nagel are responding to.

I’d also add a section entitled What is knowledge? and include:

- Dreyfus, What Computers Can’t Do — which argues that embodied, situated knowledge resists formalisation.

- Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations — not the easiest of reads, but it’s where we get notions of the impossibility of a private language and the difficulty of defining terms such as “game”.

I had to ask Perplexity for help with Part 2. I haven’t read any of these but apparently they’re relevant additions:

- How should we build AI?

- Vallor, Technology and the Virtues — A virtue-ethics framework for emerging technology which Perplexity describes as “arguably the most important contemporary work bridging classical ethics and AI practice.” The original list focuses on alignment as a technical problem, whereas Vallor asks what kind of people we need to be to build good technology.

- How might AI impact human flourishing?

- Crawford, Atlas of AI — I’ve had this book on my shelf for a while but haven’t read it yet. It’s a materialist analysis of AI’s supply chains, labour exploitation, and environmental costs, which sounded too depressing for me to read last year.

- What does AI mean for how we know things?

- Floridi, The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence — A framework of five principles for ethical AI (beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, justice, and explicability) which apparently is “the standard reference in AI governance circles.”

- Nguyen, Games: Agency as Art — Explores how gamification narrows our values into simplified metrics and therefore relevant to AI alignment. If we have to specify values precisely enough for machines to optimise, do we inevitably impoverish them?

Source: Substack Notes

Image: Hanna Barakat