Thought Shrapnel podcast: Episode #000

While the rest of Team Belshaw was doing such novel things as socialising, working, and watching TV on Friday night I decided to break out my microphone and record a solo podcast episode. Weighing in at around 20 minutes, I couldn’t in all honesty call it a ‘microcast’, so I ended up publishing using Spotify’s creator tools.

Yes, there’s an RSS feed. Is this something I want to do regularly? Is it something people want to hear? I don’t know. Perhaps I need a CONTENT STRATEGY. (I do not need a content strategy.)

We are absolutely cooked

Someone shared a link to this Instagram video in which the person on the video claims:

A friend’s daughter fed her mom’s voice to AI and then used it to get out of school to hang with her friends. She also used it to have her friends sleepover. We are absolutely cooked.

I applaud this novel use of technology by the girl. It’s not much different to my son trying to forge my signature so that I didn’t find out about his detention.

Or, indeed, me using my dad’s credit card in 1996 when I wasn’t allowed on the internet. I started sequential month-long trials with Compuserve and AOL, going to the phone box at the end of the street to call the company, pretend to be my dad, and cancel the accounts.

Yes, I get that all of this AI stuff makes it easier to scam people, but then technology has always been an arms race. Knowing how to look for the signs of what’s real and what’s fake is, therefore, a part of AI Literacy.

The rapture is not something we wait for. It's something we do.

Great stuff from Dan Meyer here. Even if he is representing an edtech company, he’s got more integrity in his little fingernail than many vendors.

I’m telling you, everybody, the problems stay the same. Every year, every decade, every new technology, the problems stay the same.

Figure out how to get along. Figure out how to share the surplus of what we build. Figure out who needs what and why they don’t have it. Figure out how to help people see that we see their value. No technology will ever change any of these unalterable challenges of human existence.

And I get it, they’re hard. It’s work. It’s also life. It’s the work of a lifetime. And I get why many people want a technological cheat code, an easy button, a rapture. But none’s coming. We’re stuck with us, people, the cause and solution of all of our problems. And new technologies can play a part, but only if we start with what people need. Teachers and students need content, sure, but especially connection.

The rapture is not something we wait for. It’s something we do.

Source: YouTube

What IPAs do you guys have on draft?

I’m a Xennial who identifies much more with Millennial culture than with Gen X. In his new column for VICE, Drew Austin (of Kneeling Bus fame) talks about the end of Millennial culture coinciding with us coming out blinking from pandemic-induced lockdowns.

It’s a fair point. I’m 44 and the youngest Millennials are around 30 years old. Popular culture belongs to people in their teens and twenties, mostly, which means that what we thought was cool and hip is now old and stale. I quite enjoyed reading this on my sticker-covered laptop while listening to music from the early 2000s on my iPod HiFi. One could say I’m comfortably settling into the second half of my life.

The monuments that have endured also attest to the generation’s decline. The electric scooter boom of the late 2010s—arguably the millennials’ swan song, and an exemplary symbol of their distinctive culture—produced a strange but predictable side effect: piles of discarded and destroyed Bird and Lime scooters littering embankments and ponds and other marginal urban spaces. The literal trashing of these whimsical avatars of the millennial economy, documented in an Instagram account called Bird Graveyard, was also a fitting metaphor for the eventual state of so many other millennial artifacts: expired but still visible, scattered throughout the urban environment, persistent reminders of an embarrassing recent past. Today, these proverbial junk piles contain more than just scooters, but also IPAs, escape rooms, listicles, smash burgers, Garden State, MySpace, brunch, @shitmydadsays, tight jeans, sans serif fonts, life hacks, axe throwing bars, Williamsburg, speakeasies, Urban Outfitters, electroclash, fast casual bowls, food trucks, food delivery apps, ridesharing apps, laundry apps—apps for every conceivable action—and even 44th US President Barack Obama himself. Much of this remains permanently embedded in the landscape. No longer fresh, it’s now just the mundane infrastructure of everyday life. What IPAs do you guys have on draft?

[…]

Every month, it seems, there’s a new thinkpiece about how millennials are washed, usually written by millennials themselves (including this one, I suppose)—but the generation seems unconvinced by its own self-deprecating argument. “Millennials’ ability to drive a cycle of discourse around our age means we can still shape the conversation,” Bernstein writes. “For millennials who criticized their boomer parents for decades for not shuffling off the stage, the ‘look how old we are’ act may serve another purpose: prolonging our own time in the spotlight, and our own sense that we are the protagonists of history.”

This kind of navel-gazing, of course, has always been a millennial hallmark. Millennials invented social media and were immediately its most dedicated users, becoming the first generation who could expect their own audience regardless of how exceptional they were, and the first to enjoy a forum where they could process their neuroses and insecurities in public. One could hardly expect millennials to bow out gracefully after 20 years of such preening online; talking is what they do best, and it’s becoming clear they’ll still be doing it when no one else is listening.

[…]

One of the emergent qualities of the digital culture millennials shaped is that nothing ends any more. Wars and pandemics drag on; aging bands keep touring in a perpetual state of reunion rather than breaking up; politicians circle the drain into their eighties and nineties; bygone aesthetics and styles are forgotten and rediscovered in shorter and shorter cycles. We seem unable to fully metabolize experiences and move on, for better or worse; we suffer from cultural acid reflux.

The paradox of the internet is that it enables this endlessness while also making culture less durable and more disposable. Millennials, again, were the first generation to bank a large share of their cultural capital online, which now seems to guarantee its swift erasure. As the generation’s Obama-era heyday recedes farther into the past, its most significant accomplishments feel increasingly elusive, hazy, out of reach, or just illegible, revealing the digital ground it all stood upon to be an unstable foundation. The rewards for millennials’ technological adventurousness have been obvious—wealth, attention, convenience, abundance of all kinds—with the drawbacks mostly becoming evident only later. And one of these drawbacks is ephemerality: The millennials’ curse is to have built their castles on sand, to see their contributions begin fading as quickly as they once appeared, to leave no lasting proof of their erstwhile relevance. The cultural significance that was attainable in the 20th century has itself become a casualty of the internet. All those moments lost in time, like tears in rain.

Source: VICE

Image: Kenny Eliason

Three clear predictors of impatience

As I’ve long suspected, researchers have found evidence that patience is not a virtue, but rather a coping strategy.

TL;DR: you’re more likely to be impatient when stuck in a particularly unpleasant state, when you want to reach an intended goal, and when someone is clearly to blame for the frustration.

So now you know.

Each hypothetical situation came in two versions, with one designed to provoke high levels of impatience, and the other only low levels. In one story, for example, the participant was asked to imagine that they were watching a film in a cinema and a child nearby was being noisy. In the ‘low impatience’ version of this scenario, the parents were doing everything they could to calm the child, while in the other, they were described as doing nothing. In addition to this, participants also completed a range of questionnaires, including a personality test and a measure of their ability to regulate their emotions.

When the team analysed the resulting data, they found three clear predictors of impatience. Participants said that they would feel more impatient when they were stuck in a particularly unpleasant state (waiting for an appointment without a seat, for example); when they particularly wanted to reach their intended goal (when they were on their way to a concert by a band they really wanted to see but were stuck in traffic); and, finally, when someone was clearly to blame for the frustration (in the cinema example, this was when the parents were described as ignoring their noisy child).

These three situation characteristics consistently provoked impatience across different scenarios, the team reports. In the third study, which also asked participants to rate the objectionableness of the situation, they found that those that had any of those three characteristics also got higher objectionableness ratings. Together, these results provide “tentative evidence” the emotion of impatience is prompted by perceiving one of these three characteristics, they write.

However, when the researchers analysed the data on how patient the participants thought they would be in the various scenarios, they found that, in general, these results were linked less to the specific situation and more to variations in individual factors. Specifically, better scores on the measures of impulsivity, emotional awareness and flexibility, and also the personality trait of agreeableness were all linked to higher patience scores.

Source: The British Psychological Society

Image: Uday Mittal

No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away

I wouldn’t usually feature one of my own posts on Thought Shrapnel but in this case there’s a couple of good reasons. First, you may not have ever listened to Today In Digital Education (TIDE), a podcast I recorded with my good friend Dai Barnes between 2015 and his tragic passing in 2019. I think you’d enjoy it.

Second, though, you may have been a listener, and somehow still have the audio files for episodes 26 and/or 37. I’m not sure how, but they currently seem lost to the sands of time. If you do have them, could you let me know? I’d love to create a complete archive.

This post is to memorialise and provide an archive for Today In Digital Education (TIDE), a podcast I recorded with my good friend Dai Barnes between 2015 and 2019. It was the second podcast I co-hosted with him, the first being EdTechRoundUp from 2007 to 2011.

[…]

Dai sadly passed away suddenly in his sleep in early August 2019. In the eulogy I gave for Dai at Oundle School, I quoted Terry Pratchett as saying that “No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away.” I still miss Dai and know his ripples continue on through many of us.

Source: Open Thinkering

Image: Snappy Shutters

The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of transformation and adaptation

The headline that The Guardian chose to use for this article is “Climate crisis on track to destroy capitalism, warns top insurer.” I mean, if only.

But, of course, the reality is entirely the opposite way around: capitalism is destroying the climate. The only thing that provides some solace in this article is the realisation that people, organisations, and governments will be unable to get insurance, which will in turn put (positive) pressure on Net Zero targets.

At least, I hope that will be the case. Otherwise we’re going to have a Mad Max-style world on fire with lots of poverty and migration.

The world is fast approaching temperature levels where insurers will no longer be able to offer cover for many climate risks, said Günther Thallinger, on the board of Allianz SE, one of the world’s biggest insurance companies. He said that without insurance, which is already being pulled in some places, many other financial services become unviable, from mortgages to investments.

Global carbon emissions are still rising and current policies will result in a rise in global temperature between 2.2C and 3.4C above pre-industrial levels. The damage at 3C will be so great that governments will be unable to provide financial bailouts and it will be impossible to adapt to many climate impacts, said Thallinger, who is also the chair of the German company’s investment board and was previously CEO of Allianz Investment Management.

The core business of the insurance industry is risk management and it has long taken the dangers of global heating very seriously. In recent reports, Aviva said extreme weather damages for the decade to 2023 hit $2tn, while GallagherRE said the figure was $400bn in 2024. Zurich said it was “essential” to hit net zero by 2050.

[…]

No governments will realistically be able to cover the damage when multiple high-cost events happen in rapid succession, as climate models predict, Thallinger [on the board of Allianz SE, one of the world’s biggest insurance companies] said. Australia’s disaster recovery spending has already increased sevenfold between 2017 and 2023, he noted.

[…]

Many financial institutions have moved away from climate action after the election of the US president, Donald Trump, who has called such action a “green scam”. Thallinger said in February: “The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of transformation and adaptation. If we succeed in our transition, we will enjoy a more efficient, competitive economy [and] a higher quality of life.”

Source: The Guardian

Image: Mika Baumeister

The Great Democratization Cycle

This article by Pete Sena is a curious one. On the one hand, he makes some really solid points about ‘vibe coding’ which I’d define as using natural language to create digital artefacts containing code. Most commonly these are web apps, such as the ones I’ve created:

- Album Shelf — make virtual shelves of music albums to set as your video conference background

- Badge to the Future — a Verifiable Credentials issuing and portfolio platform

- Career Discovery Tool — a question-based tool using the Perplexity and Lightcast APIs to find which jobs might be suitable (and less likely to be automated)

Sena goes on, however, to start talking about ‘craft’, as if somehow lots of people being able to manipulate code is going to destroy the industry. It won’t. There will just a lot more people being able to go from idea to execution quickly.

Does that mean that every vibe coded app will be scalable and secure? Obviously not. But this is the worst the technology is going to be, so buckle up, folks! If you’re interested in a potential course I’m going to offer around all this, you can sign up at vibe.horse.

Vibe coding is also just one more example of what I call the Great Democratization Cycle. We’ve seen it in photography as it evolved from darkrooms to digital cameras, which eliminated film processing, to smartphones and Instagram filters, making everyone a high-end “photographer.” The same goes for publishing (from printing presses to WordPress), video production (from studio equipment to TikTok), and music creation (from recording studios to GarageBand on a laptop and now AI tools like Suno on your smartphone).

[…]

This AI-driven accessibility is undeniably powerful. Designers can prototype without developer dependencies. Domain experts can build tools to solve specific problems without learning Python. Entrepreneurs can validate concepts without hiring engineering teams.

But as we embrace this new paradigm, we face a profound question: What happens when we separate makers from their materials?

[…]

Consider this parallel: Would we celebrate a world where painters never touch paint, sculptors never feel clay, or chefs never taste their ingredients? Would their art, their craft, retain its soul?

When we remove the intimate connection between creator and medium — in this case, between developer and code — we risk losing something essential: the craft.

[…]

True innovation often emerges from constraints and deep domain knowledge. When you wrestle with a programming language’s limitations, you’re forced to think creatively within boundaries. This tension produces novel solutions and unexpected breakthroughs.

When we remove this friction entirely, we risk homogenizing our solutions. If everyone asks AI for “a responsive e-commerce site with product filtering,” we’ll get variations on the same theme — technically correct but creatively bankrupt implementations that feel eerily similar.

Source: Peter Suna

Image: BoliviaInteligente

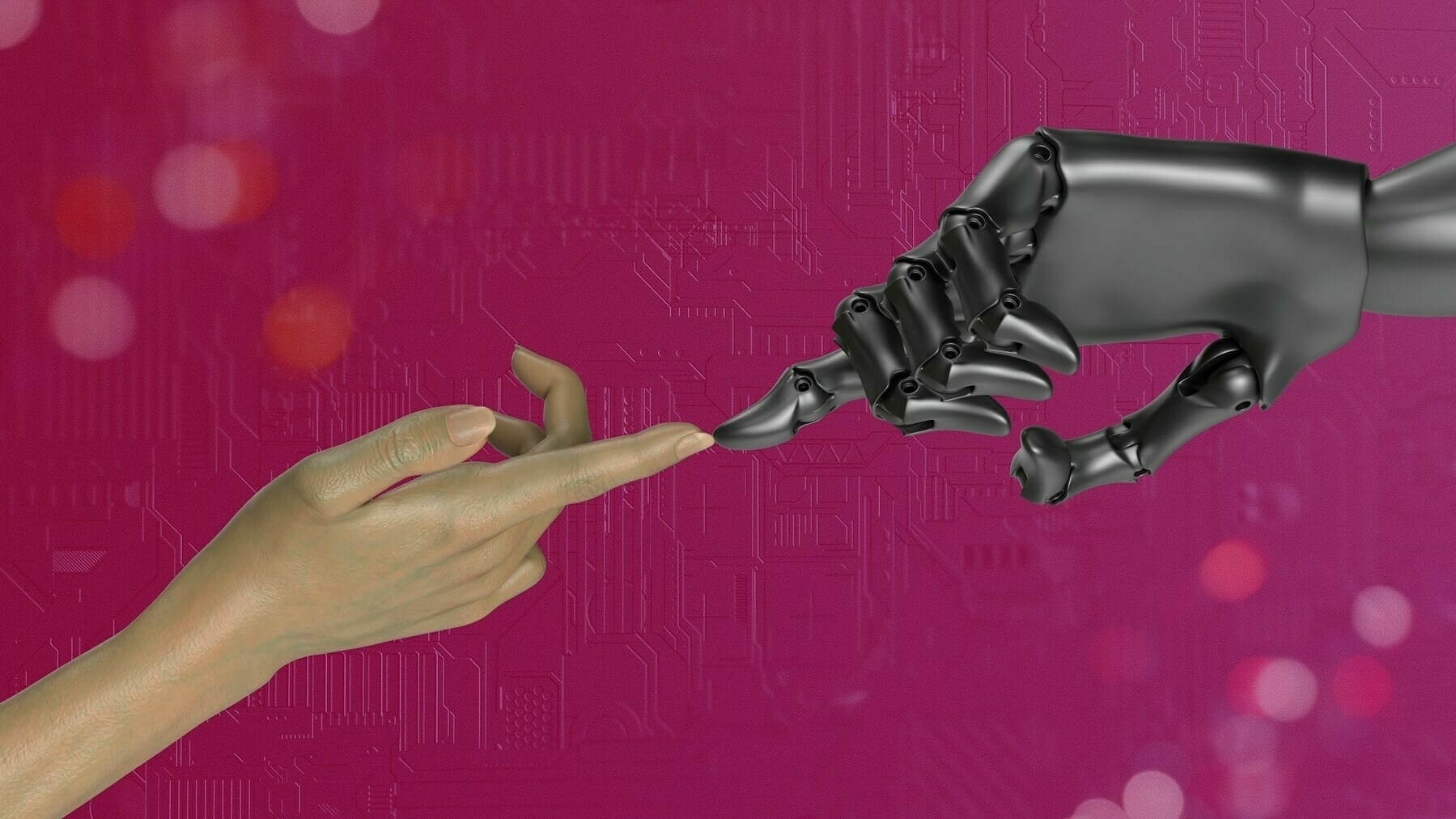

I warned that LLMs would be used for dumb things that would affect lots of people

I’m a daily, but not uncritical, user of generative AI. One of the particularly problematic uses of the technology is of an objective, neutral, and all-knowing arbiter for decision making.

It’s bad enough doing this on a local level, when not many people are involved. It’s much worse when brought in, say, to the benefits system and of course, much much worse when used (allegedly) to dictate punitive tariffs.

In Taming Silicon Valley, I warned that LLMs would be used for dumb things that would affect lots of people.

I rest my case.

Source & screenshot: Marcus on AI

To cope, the brain improvises

My wife’s favourite colour is purple. Which, doesn’t really exist — it’s a nonspectral colour. But then, strictly speaking, no colours exist. Phenomenology FTW.

Our eyes can’t see most wavelengths, such as the microwaves used to cook food or the ultraviolet light that can burn our skin when we don’t wear sunscreen. We can directly see only a teeny, tiny sliver of the spectrum — just 0.0035 percent! This slice is known as the visible-light spectrum. It spans wavelengths between roughly 350 and 700 nanometers.

[…]

Although violet is in the visible spectrum, purple is not. Indeed, violet and purple are not the same color. They look similar, but the way our brain perceives them is very different.

[…]

When light enters our eyes, the specific combination of cones it activates is like a code. Our brain deciphers that code and then translates it into a color.

Consider light that stimulates long- and mid-wavelength cones but few, if any, short-wavelength cones. Our brain interprets this as orange. When light triggers mostly short-wavelength cones, we see blue or violet. A combination of mid- and short-wavelength cones looks green. Any color within the visible rainbow can be created by a single wavelength of light stimulating a specific combination of cones.

[…]

In the middle of the rainbow — colors like green and yellow — the mid-wavelength cones are busiest, with help from both long- and short-wavelength cones. At the blue end of the spectrum, short-wavelength cones do most of the work.

But there is no color on the spectrum that’s created by combining long- and short-wavelength cones.

[…] Purple is a mix of red (long) and blue (short) wavelengths. Seeing something that’s purple… stimulates both short- and long-wavelength cones. This confuses the brain. […]

To cope, the brain improvises. It takes the visible spectrum — usually a straight line — and bends it into a circle. This puts blue and red next to each other.

[…]

Colors that are part of the visible spectrum are known as spectral colors. It only takes one wavelength of light for our brain to perceive shades of each color. Purple, however, is a nonspectral color. That means it’s made of two wavelengths of light (one long and one short).

Source: ScienceNewsExplores

Image: Luke Chesser

The future of the many diasporas which already characterize our present

I was all ready to summarise a post about an internet of many autonomous communities, but what really caught my eye was an article the author links to from 2017.

I’ve already referenced Episode #324 (“What’s Good for the Goose”) of Dan Carlin’s Common Sense podcast this week, and will do so again in relation to this. We’re entering a point in history where the assumptions made at the founding of nation states are being challenged by the digital technologies that allow instant communication between continents.

Ada Palmer is a novelist and historian, whose award-winning Terra Ignota series explores a future of borderless nations. If we stop and think for a moment, those who work from home and don’t have much of a geo-specific social life (🙋), can already choose to live quite differently to their neighbours. I can only seeing that becoming even more the case over time.

What if citizenship wasn’t something we’re born with, but something we choose when we grow up? In the Terra Ignota future, giant nations called “Hives” are equally distributed all around the world, so every house on a block, and even every person in a house, gets to choose which laws to live by, and which government represents that individual’s views the most. It’s an extension into the future of the many diasporas which already characterize our present, since increasingly easy transportation and communication mean that families, school friends, social groups, ethnic groups, language groups, and political parties are already more often spread over large areas than residing all together. In this future each of those groups can be part of one self-governing nation, with laws that fit their values, even while all living spread over the same space.

Source & image: The Reactor

We create more than ever, but it weighs nothing

I discovered this post by Dougald Hine via Warren Ellis, which in turn links to Anu’s exhortation to ‘make something heavy’.

The identification of people being ‘pre-heavy thing’ or ‘post-heavy thing’ is an interesting concept. Perhaps I need to think about my next heavy thing?

If something is heavy, we assume it matters. And often, it does. Weight signals quality, durability, presence, permanence.

[…]

We accept this in the physical world.

But online, we forget.

[…]

The modern makers’ machine does not want you to create heavy things. It runs on the internet—powered by social media, fueled by mass appeal, and addicted to speed. It thrives on spikes, scrolls, and screenshots. It resists weight and avoids friction. It does not care for patience, deliberation, or anything but production.

It doesn’t care what you create, only that you keep creating. Make more. Make faster. Make lighter. (Make slop if you have too.) Make something that can be consumed in a breath and discarded just as quickly. Heavy things take time. And here, time is a tax. And so, we oblige—everyone does. We create more than ever, but it weighs nothing.

[…]

Creation isn’t just about output. It’s a process of becoming. The best work shapes the maker as much as the audience. A founder builds a startup to prove they can. A writer wrestles an idea into clarity. You don’t just create heavy things. You become someone who can.

[…]

At any given time, you’re either pre–heavy thing or post–heavy thing. You’ve either made something weighty already, or you haven’t. Pre–heavy thing people are still searching, experimenting, iterating. Post–heavy thing people have crossed the threshold. They’ve made something substantial—something that commands respect, inspires others, and becomes a foundation to build on. And it shows. They move with confidence and calm. (But this feeling doesn’t always last forever.)

Source: Working Theorys

Image: Keagan Henman

The vaunted first amendment guaranteeing free speech has become a bitter and twisted joke

As I’ve seen other post about, there’s no easy way to calculate the impact and lost value of the research that won’t be done, the breakthroughs that won’t be made, and the collaborations that won’t happen as a result of the oligarchy currently taking over the US political system.

In this post, Prof. Christina Pagel gives just one small example of the self-censorship ‘just in case’ that will be happening everywhere. I didn’t travel to the US last year because it felt like an unsafe to visit; I sure as hell ain’t going this year.

Relatedly, I’d highly recommend listening to Episode #324 (“What’s Good for the Goose”) of Dan Carlin’s Common Sense podcast as it puts current events in a wider context.

A colleague and I would like to write an academic paper on the potential impact of US funding cuts to global health programmes. Our ideal co-author is an international expert newly based in the US, and they would like to do it. But we are all worried that doing so will expose them to the risk of having their academic visa cancelled, being detained and eventually deported - no matter how solid the science and how academic and dry our language. We are especially fearful because they are brown.

My colleagues who have been writing about the new administration, or the situation in Gaza, in academic journals, on substack or on social media are cancelling work trips to the US. I too would not feel safe to go now, given how openly I have criticised the administration. Even a 1% chance of being denied entry or shipped to a detention centre is too high.

When I said these words out loud to my husband today I had to stop for a moment to let it sink in. Foreign scientists in the US are scared to publish anything perceived as critical for fear of being bundled off the street to a detention centre. Foreign scientists abroad are scared to go to the US because they have voiced criticism of the state. The US is actively cracking down on perceived dissenters and foreigners are the most vulnerable to arbitrary detention and lack of due legal process. The vaunted first amendment guaranteeing free speech has become a bitter and twisted joke.

Source: Diving into Data & Decision making

Image: Floris Van Cauwelaert

The Ghibli crisis is just the beginning

As I’ve argued many times, including just last week appending ‘literacy’ to a word is an attempt at control. It’s a power move, either intentionally or unintentionally. So, for example, with the work that I’ve been kicking off around AI Literacy recently with the BBC, it’s interesting to see the way that, for example, Big Tech wants to define it compared to, say, academics.

In this post, Jay Springett introduces the term ‘context literacy’ but doesn’t really define what it means. I don’t doubt that what he identifies in the post isn’t a set of important skills and competencies, but is it a ‘literacy’? Is it a way of metaphorically ‘reading’ and ‘writing’? Or is it just a way of understanding and making sense of the world?

I definitely agree that we’re in the midst of another culture war that, perhaps more than ever before, is predicated on a lack of shared context. I’ve started watching the Contrapoints video I shared recently about conspiracism, which I think is very closely related to this.

The Ghibli crisis is just the beginning. Focusing on the outputs alone misses the point.

So how do we respond?

We must recognise that revolution is not over. We are in the Information Age.

We must cultivate context literacy and we must maintain a distinction between the infrastructure and the experience, between machine and meaning.

We are living through a moment that future historians may describe as a cultural rupture. A context war. How this plays out will shape new definitions of truth, authorship, creativity, and trust, perhaps for centuries to come.

The question is not whether this will happen.

It already is.

Source: thejaymo

Organisations will need to change their analogies

Ethan Mollick reports on a study last summer with 776 professionals at Procter and Gamble. The findings, pretty obviously, show that working with AI boosts performance, but also that working in teams is just as effective as working with AI. Teams working with AI “were significantly more likely to produce… top-tier solutions.”

What’s interesting to me, though, is the emotional aspect of all this. Unless you’ve done work around, say, nonviolent communication and Sociocracy it’s likely to that you experience regular unprocessed negative emotions around work. Especially if you work in a hierarchical setting.

Generative AI can be particularly good at helping you think more objectively about work — as being something that you have ideas and thoughts about, rather than emotions. At least, it does for me. Note that I definitely think that you should bring your full self to work, it’s just that unhelpful negative emotions can sometimes creep in to our relationships with other humans, especially around the validation (or otherwise) of ideas.

For me, the sweet spot is working with people I know, respect, and trust (i.e. my colleagues at WAO) and using generative AI to augment our collaboration.

A particularly surprising finding was how AI affected the emotional experience of work. Technological change, and especially AI, has often been associated with reduced workplace satisfaction and increased stress. But our results showed the opposite, at least in this case.

People using AI reported significantly higher levels of positive emotions (excitement, energy, and enthusiasm) compared to those working without AI. They also reported lower levels of negative emotions like anxiety and frustration. Individuals working with AI had emotional experiences comparable to or better than those working in human teams.

While we conducted a thorough study that involved a pre-registered randomized controlled trial, there are always caveats to these sorts of studies. For example, it is possible that larger teams would show very different results when working with AI, or that working with AI for longer projects may impact its value. It is also possible that our results represent a lower bound: all of these experiments were conducted with GPT-4 or GPT-4o, less capable models than what are available today; the participants did not have a lot of prompting experience so they may not have gotten as much benefit; and chatbots are not really built for teamwork. There is a lot more detail on all of this in the paper, but limitations aside, the bigger question might be: why does this all matter?

[…]

To successfully use AI, organizations will need to change their analogies. Our findings suggest AI sometimes functions more like a teammate than a tool. While not human, it replicates core benefits of teamwork—improved performance, expertise sharing, and positive emotional experiences. This teammate perspective should make organizations think differently about AI. It suggests a need to reconsider team structures, training programs, and even traditional boundaries between specialties. At least with the current set of AI tools, AI augments human capabilities. It democratizes expertise as well, enabling more employees to contribute meaningfully to specialized tasks and potentially opening new career pathways.

The most exciting implication may be that AI doesn’t just automate existing tasks, it changes how we can think about work itself. The future of work isn’t just about individuals adapting to AI, it’s about organizations reimagining the fundamental nature of teamwork and management structures themselves. And that’s a challenge that will require not just technological solutions, but new organizational thinking.

Source: One Useful Thing

Image: Igor Omilaev

Once you become aware of Hyperlegibility, you see it everywhere

I think the author of this article, Packy McCormick, has essentially discovered “working openly.” But, I guess, the twist is that it’s doing so in a way that makes your ideas accessible and understandable to as many people as possible.

It’s interesting doing this in an age of AI, because (as McCormick) does, you can half-remember something, type it into an LLM, and have it find the thing you’re talking about, with sources, extremely quickly.

If ‘hyperlexic’ describes extraordinary reading ability, then let me propose a complementary word for extraordinary readability: Hyperlegible.

Hyperlegibility defines our current era so comprehensively that I was shocked when I googled the term and found only references to fonts.

[…]

Hyperlegibility emerges with game theoretical certainty from each of our desire to win whatever game it is you’re playing. Certainly, it’s a consequence of playing The Great Online Game. In order for the right people and projects to find you, you must make yourself legible to them. To stand out in a sea of people making themselves legible, you must make yourself Hyperlegible: so easy to read and understand you rise to the top.

Once you become aware of Hyperlegibility, you see it everywhere.

[…]

Hyperlegibility isn’t good or bad. It’s neither and both. But it certainly is. Information used to be the highest form of alpha. Now everyone bends over backwards to leak it.

Through a combination of humanity getting ever-better at reading anything and humans becoming ever-more willing to make themselves legible, information is easier to find and understand than it’s ever been.

Source: Not Boring

Image: Egor Myznik

Less anonymity online is not going to make things better

I use the Switzerland-based service Proton for my personal email and VPN, so news that the Swiss government is considering amending its surveillance law isn’t great news.

It looks like the specific thing they’re targeting is the metadata — i.e. not the content of the message, but where it was sent from and to whom. That’s the kind of information that Meta collects when people use WhatsApp. By way of comparison, Proton is more like Signal messenger in they don’t harvest this kind of metadata.

You might wonder why this is important, but putting together a story based on metadata isn’t exactly difficult. And, as is well-attested, if you have enough metadata, you don’t really need the content of the messages.

Consultations are now public and open until May 6, 2025. Speaking to TechRadar, NymVPN has explained how it’s planning to fight against it, alongside encrypted messaging app Threema and Proton, the provider behind one of the best VPN and secure email services on the market.

Authorities' arguments behind the need for accessing more data are always the same – catching criminals and improving security. Yet, according to Nym’s co-founder and COO, Alexis Roussel, being forced to leave more data behind would achieve the opposite result.

“Less anonymity online is not going to make things better,” he told TechRadar. “For example, enforcing identification of all these small services will eventually push to leaks, more data theft, and more attacks on people.”

[…]

“It’s not about end-to-end encryption. They don’t want to force you to reveal what’s inside the communication itself, but they want to know where it goes,” Roussel explains. “They realize the value is not in what is being said but who you are talking to.”.

“The whole point of security and privacy is not being able to link the usage to the person. That’s the most critical thing.” Roussel told TechRadar.

Source: TechRadar

Image: Arturo A

You do not have to participate in the lottery

This is the first post I’ve come across from Paras Chopra, and I love the strapline for his blog: “Be passionate about the territory, not the map.” He’s still young, and the overall philosophy of life he outlines here is a touch naive (reminding me of myself at that age) but nevertheless it’s solid advice.

In most modern cultures, direct coercion doesn’t exist. Nobody can make you work harder than you want to. However, with our infinite algorithmic timelines, we’re immersed with indirect coercion.

But, you do not have to participate in the lottery. You can choose to quit. You can decide to not compete. You can choose to not participate in the lottery, where you’d almost likely lose more than you receive in return.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean inactivity. (Life is a game, where inactivity means death.)

Rather, what this implies is something very simple – don’t confuse what gets social approval with what’s right for you. Social approval exists to attract participants in a game that ultimately benefits the collective at the expense of an individual.

[…]

Once you overcome your desire to compete with others, you can actually just sit back and enjoy the outcomes that others compete to produce for you.

[…]

Let others compete hard to let you enjoy these things, while you do what you find most fun. It could be tending to your garden, working at a sensible pace, making coffee, building tiny weird games, or whatever else makes you come alive.

I hear you ask: won’t society collapse if everyone did this? I’d argue the opposite. If everyone did what they find most fulfilling, our net happiness will rise. Artifacts useful to the society will still be produced, except with less anxiety and burnout. People will still write books, but without an intent of it trying to be a bestseller but with an intent of honing and enjoying their craft.

Source: Inverted Passion

Image: dylan nolte

Things have changed

I know Martin Waller from the early days of Twitter when we were both teachers. The ‘Multi’ part of his ‘MultiMartin’ handle is due to his work on multiliteracies, the subject of his postgraduate study. He’s written plenty of papers and spoken at more than a few events.

Martin dropped off my radar a bit, but on reconnecting with him this week, he pointed me towards this post. I think we’re going to see a lot more of this over the next few years. How would Gwyneth Paltrow put it, “conscious decoupling” from online life, maybe?

I’ve… taken the decision to completely remove myself from social media including most online messaging services. I was once an advocate of the use of social media and digital technologies and have published book chapters and spoken at events around the world about it in education. I have made so many wonderful connections and friends over the years on the internet and through social media. However, things have changed. The landscape and current climate can be toxic and dangerous. I’ve stumbled upon comments on Facebook and Instagram which have made me feel sick. I’ve read different messenger channels where comments have ridiculed people for no good reason. There’s also just too much information out there and it isn’t helpful to be exposed to it all, all of the time. It makes it difficult to switch off, think and focus on what matters.

Source: MultiMartin

Image: Chris Barbalis

A bit of composting

There’s a lot of people thinking about endings at the moment. Not just because we’re getting into the post-Covid era now, but also due to things like the huge swathes of layoffs in the US, and the general economic downturn in the UK and other countries.

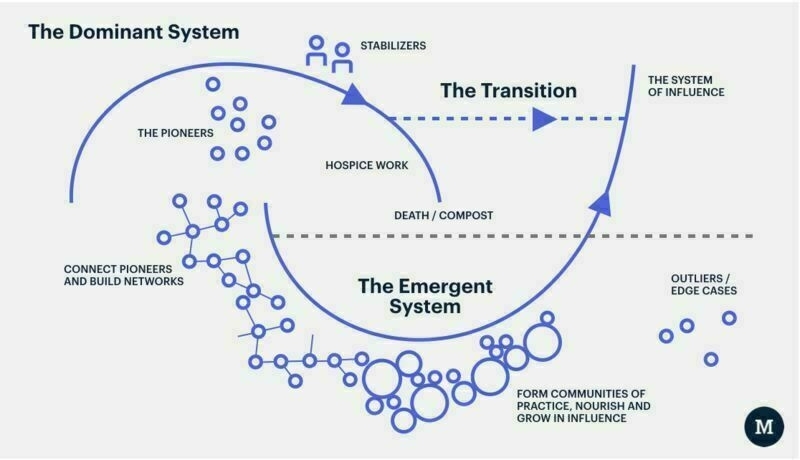

Things start and things end. That’s what they do. Change is constant, which is something difficult to get used to. In this post, Tom Watson talks about ‘composting’ which is a key part of the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops model, which he doesn’t actually reference but is extremely relevant.

I’d also say working openly helps with having good endings. The chances are that what has been learned during the project can take root elsewhere, and therefore live on, if people can see into the project. We should treat projects less as raised beds for pretty flowers and more like mycelium networks.

I thought about the social enterprise I had with my dad. I’ve got lots of things wrong in life, but doing that definitely wasn’t one of them. I learned a lot, about caring, kindness, not following the bullshit, and community. It ended, like all organisations do. But I was proud that we were able to financially support a group to continue meeting and chatting, and supporting each other. It wasn’t much, but it was something. And just last year we donated the last of our funds, around £6k, to a charity rewilding in Scotland, where the C for Campbell in my name comes from via my dad.

This felt like a good ending. A bit of composting. But not every organisation can pass on finances at the end, in fact it’s pretty rare, because often the root cause of the ending is money. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have things of value to pass on. They have resources, knowledge and wisdom. And I couldn’t help thinking about all that is lost, again and again when things end.

[…]

[W]e need to think broader about endings and composting. Not just when an organisation ends, but when programmes and projects end. What about all the research reports, the data from projects, the experiments that worked and those that didn’t. What about all that knowledge, what about all that potential wisdom. It’s why we spend time up front cataloguing all the things we do in a project along the way. It’s not perfect, but it’s something.

Source: Tomcw.xyz

Image: Innovation Unit