Games (and learning) mechanics

The average age of those who play video games? Early thirties, and rising. So, I’m happy to say that purchasing Red Dead Redemption 2 is one of the best decisions I’ve made so far in 2019.

It’s an incredible, immersive game within which you could easily lose a few hours at a time. And, just like games like Fortnite, it’s being tweaked and updated after release to improve the playing experience. Particularly the online aspect.

What interests me in particular as an educator and a technologist is the way that the designers are thinking carefully about the in-game mechanics based on what players actually do. It’s easy to theorise what people might do, but what they actually do is a constant surprise to anyone who’s ever designed something they’ve asked another person to use.

Engadget mentions one update to Red Dead that particularly jumped out at me:

The update also brings a new system that highlights especially aggressive players. The more hostile you are, the more visible you will become to other players on the map with an increasingly darkening dot. Your visibility will increase in line with bad deeds such as attacking players and their horses outside of a structured mode, free roam mission or event. But, start behaving, and your visibility will fade over time. Rockstar is also introducing the ability to parlay with an entire posse, rather than individual players, which should also help to reduce how often players are killed by trolls.In other words, anti-social behaviour is being dealt with by games mechanics that make it harder for people to act inappropriately.

But my favourite update?

The update will also see the arrival of bounties. Any player that's overly aggressive and consistently breaks the law with have a bounty placed on their head, and once it's high enough NPC [Non-Playing Characters] bounty hunters will get on your tail. Another mechanism to dissuade griefing but perhaps a missed opportunity to allow players to become temporary bounty hunters and enact some sweet vengeance on the players that keep ruining their gameplay.We have a tendency in education to simply ban things we don't like. That might be excluding people from courses, or ultimately from institutions. However, when it's customers at stake, games designers have a wide range of options to influence the outcomes for the positive.

I think we’ve got a lot still to learn in education from games design.

Source: Engadget

Image by BagoGames used under a CC BY license

Is edtech even a thing any more?

Until recently, Craig Taylor included the following in his Twitter bio:

Dreaming of a day when we can drop the e from elearning and the m from mobile learning & just crack on.Last week, I noticed that Stephen Downes, in reply to Scott Leslie on Mastodon, had mentioned that he didn't even think that 'e-learning' or 'edtech' was really a thing any more, so perhaps Craig dropping that from his bio was symptomatic of a wider shift?

I'm not sure anyone has any status in online learning any more. I'm wondering, maybe it's not even a discipline any more. There's learning analytics and open pedagogy and experience design, etc., but I'm not sure there's a cohesive community looking at what we used to call ed tech or e-learning.His comments were part of a thread, so I decided not to take it out of context. However, Stephen has subsequently written his own post about it, so it's obviously something on his mind.

Reflecting on what he covers in OLDaily, he notes that, while everything definitely falls within something broadly called ‘educational technology’, there’s very few people working at that meta level — unlike, say, ten years ago:

[I]n 2019 there's no community that encompasses all of these things. Indeed, each one of these topics has not only blossomed its own community, but each one of these communities is at least as complex as the entire field of education technology was some twenty years ago. It's not simply that change is exponential or that change is moving more and more rapidly, it's that change is combinatorial - with each generation, the piece that was previously simple gets more and more complex.I think Stephen's got what Venkatesh Rao might deem an 'elder blog':

The concept is derived from the idea of an elder game in gaming culture -- a game where most players have completed a full playthrough and are focusing on second-order play.In other words, Stephen has spent a long time exploring and mapping the emerging territory. What's happening now, it could be argued, is that new infrastructure is emerging, but using the same territory.

So, to continue the metaphor, a new community springs up around a new bridge or tunnel, but it’s not so different from what went before. It’s more convenient, maybe, and perhaps increases capacity, but it’s not really changing the overall landscape.

So what is the value of OLDaily? I don't know. In one sense, it's the same value it always had - it's a place for me to chronicle all those developments in my field, so I have a record of them, and am more likely to remember them. And I think it's a way - as it always has been - for people who do look at the larger picture to stay literate. Not literate in the sense of "I could build an educational system from scratch" but literate in the sense of "I've heard that term before, and I know it refers to this part of the field."I find Stephen's work invaluable. Along with the likes of Audrey Watters and Martin Weller, we need wise voices guiding us — whether or not we decide to call what we're doing 'edtech'.

Source: OLDaily

Optimise for energy and motivation

While this post has a clickbait-y subtitle (‘Why I quit a $500K job at Amazon to work for myself’) it nevertheless makes an important point:

Last week I left my cushy job at Amazon after 8 years. Despite getting rewarded repeatedly with promotions, compensation, recognition, and praise, I wasn’t motivated enough to do another year.As author Daniel Pink points out in his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, when it comes down to it, neither money nor people saying "good job" is why we go to work. We want to do stuff that's meaningful.

What kind of work would I do if I had to do it forever? Not something that I did until I reached some milestone (an exit), but something that I would consider satisfactory if I continued to do it until I’m 80. What is out there that I could do that would make me excited waking up every day for the next 45 years that could also earn me enough money to cover my expenses? Is that too unambitious? I don’t think so.I'm nowhere near this guy's earnings, but I do earn about twice as much as I did as a senior leader in schools. That would have been a ridiculous amount of money to me a few years ago, but you get used to it. The point is that you have to be doing something sustainable.

The things that don’t wear off are those that I’ve been doing since I was a kid, when nothing was forcing me to do them. Things such as writing code, selling my creations, charting my own path, calling it like I saw it. I know my strengths, and I know what motivates me, so why not do this all the time? I’m lucky to live in a time where I can do something independently in my area of expertise without requiring large amounts of capital or outside investors. So that’s what I’m doing.A couple of weeks ago I volunteered to be an Assistant Scout Leader. I realised how much I missed interacting with kids of that age (over and above my own, of course) but teaching isn't the only way of going about doing that.

The interesting thing is that, if you do something you find interesting, something that gets you out of bed in the morning, the money will come at some point. I’m not naive enough to think that “follow your dreams” is good career advice, but you certainly shouldn’t be doing something you hate. Not long-term, anyway.

On that note, it’s been a delight to see how Bryan Mathers is pulling together his artistic chops (which he’s honed from zero this decade) and his coding skills to create The Remixer Machine. It seemed to come from nowhere but, of course, it’s taken skills and interests that he’s combined to make something worthwhile in the world.

So, what can you do practically if you’re reading this? Optimise for energy and motivation. In practice, that means do something that you love at a time you’ve got most energy. If you’re a morning person, do something that inspires you before work. If you’re super-motivated around lunchtime, do something in your lunch break. Night owl? You know what to do…

Source: Daniel Vassallo

Process and product of change (quote)

“To be in process of change is not an evil, any more than to be the product of change is a good.”

(Marcus Aurelius)

Why the internet is less weird these days

I can remember sneakily accessing the web when I was about fifteen. It was a pretty crazy place, the likes of which you only really see these days in the far-flung corners of the regular internet or on the dark web.

Back then, there were conspiracy theories, there was porn, and there was all kinds of weirdness and wonderfulness that I wouldn’t otherwise have experienced growing up in a northern mining town. Some of it may have been inappropriate, but in the main it opened my eyes to the wider world.

In this Engadget article, Violet Blue points out that the demise of the open web means we’ve also lost meaningful free speech:

It's critical... to understand that apps won, and the open internet lost. In 2013, most users accessing the internet went to mobile and stayed that way. People don't actually browse the internet anymore, and we are in a free-speech nightmare.A very real problem for society at the moment is that we simultaneously want to encourage free-thinking and diversity while at the same time protecting people from distasteful content. I’m not sure what the answer is, but outsourcing the decision to tech companies probably isn’t the answer.Because of Steve Jobs, adult and sex apps are super-banned from Apple’s conservative walled garden. This, combined with Google’s censorious push to purge its Play Store of sex has quietly, insidiously formed a censored duopoly controlled by two companies that make Morality in Media very, very happy. Facebook, even though technically a darknet, rounded it out.

In 1997, Ann Powers wrote an essay called "In Defense of Nasty Art." It took progressives to task for not defending rap music because it was "obscene" and sexually graphic. Powers puts it mildly when she states, "Their apprehension makes the fight to preserve freedom of expression seem hollow." This is an old problem. So it's no surprise that the same websites forbidding, banning, and blocking "sexually suggestive" art content also claim to care about free speech.As a parent of a 12 year-old boy and eight year-old girl, I check the PEGI age ratings for the games they play. I also trust Common Sense Media to tell me about the content of films they want to watch, and I'm careful about what they can and can't access on the web.

Violet Blue’s article is a short one, so focuses on the tech companies, but the real issue here is one level down. The problem is neoliberalism. As Byung-Chul Han comments in Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power, which I’m reading at the moment:

Neoliberalism represents a highly efficient, indeed an intelligent, system for exploiting freedom. Everything that belongs to practices and expressive forms of liberty –emotion, play and communication –comes to be exploited.Almost everything is free at the point of access these days, which means, in the oft-repeated phrase, that we are the product. This means that in order to extract maximum value, nobody can be offended. I'm not so sure that I want to live in an inoffensive future.

Dis-trust and blockchain technologies

Serge Ravet is a deep thinker, a great guy, and a tireless advocate of Open Badges. In the first of a series of posts on his Learning Futures blog he explains why, in his opinion, blockchain-based credentials “are the wrong solution to a false problem”.

I wouldn’t phrase things with Serge’s colourful metaphors and language inspired by his native France, but I share many of his sentiments about the utility of blockchain-based technologies. Stephen Downes commented that he didn’t like the tone of the post, with “the metaphors and imagery seem[ing] more appropriate to a junior year fraternity chat room that to a discussion of blockchain and academics”.

It’s not my job as a commentator to be the tone police, but rather to gather up the nuggets and share them with you:

My attention was recently attracted to an article describing blockchains as “distributed trust” which they are not, but makes a nice and closer to the truth acronym: dis-trust…Blockchains are, in some circumstances, a great replacement for a centralised database. I find it difficult to get excited about that, as does Serge:

It is time for a copernican revolution, moving Blockchains from the centre of all designs to its periphery, as an accessory worth exploiting, or not. If there is a need for a database, the database doesn’t have to be distributed, if there are decisions to be made, they do not have to be left to an inflexible algorithm. On the other hand, if the design requires computer synchronisation, then blockchains might be one of the possible solutions, though not the only one.One of the difficulties, of course, is that hype perpetuates hype. If you're a vendor and your client (or potential client) asks you a question, you'd better be ready with a positive answer:

In the current strands for European funding, knowing that the European Union has decided to establish a “European blockchain infrastructure” in 2019, who will dare not to mention blockchains in their responses to the calls for tenders? And if you are a business and a client asks “when will you have a blockchain solution” what is the response most likely to get her attention: that’s not relevant to your problem or we have a blockchain solution that just matches your needs? How to resist the blockchain mania while providing clients and investors with something that sounds like what they want to hear?It's been four years since I first wrote about blockchain and badges. Since then, I co-founded a research project called BadgeChain, reflected on some of Serge's earlier work about a 'bit of trust', confirmed that BlockCerts and badges are friends, commented on why blockchain-based credentials are best used for high-stakes situations, written about blockchain and GDPR, called out blockchain as a futuristic integrity wand, agreed with Adam Greenfield that blockchain technologies are a stepping stone, reflected on the use of blockchain-based credentials in Higher Education, sighed about most examples of blockchain being bullshit, and explained that blockchain is about trust minimisation.

I think you can see where people like Serge and I stand on all this. It’s my considered opinion that blockchain would not have been seen as a ‘sexy’ technology if there wasn’t a huge cryptocurrency bubble attached to it.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: you need to understand a technology before you add it to the ‘essential’ box for any given project. There are high-stakes use cases for blockchain-based credentials, but they’re few and far between.

Source: Learning Futures

Image adapted from one in the Public Domain

Why it's so hard to quit Big Tech

I’m writing this on a Google Pixelbook. Earlier this evening I wiped it, fully intending to install Linux on it, and then… meh. Partly, that’s because the Pixelbook now supports Linux apps in a sandboxed environment (which is great!) but mostly because using ChromeOS on decent hardware is just a lovely user experience.

Writing for TechCrunch, Danny Crichton writes:

Privacy advocates will tell you that the lack of a wide boycott against Google and particularly Facebook is symptomatic of a lack of information: if people really understood what was happening with their data, they would galvanize immediately for other platforms. Indeed, this is the very foundation for the GDPR policy in Europe: users should have a choice about how their data is used, and be fully-informed on its uses in order to make the right decision for them.This is true for all kinds of things. If people only knew about the real cost of Brexit, about what Donald Trump was really like, about the facts of global warning... and on, and on.

I think it’s interesting to compare climate change and Big Tech. We all know that we should probably change our actions, but the symptoms only affect us directly very occasionally. I’m just pleased that I’ve been able to stay off Facebook for the last nine years…

Alternatives exist for every feature and app offered by these companies, and they are not hard to find. You can use Signal for chatting, DuckDuckGo for search, FastMail for email, 500px or Flickr for photos, and on and on. Far from being shameless clones of their competitors, in many cases these products are even superior to their originals, with better designs and novel features.It's not good enough just to create a moral choice and talk about privacy. Just look at the Firefox web browser from Mozilla, which now stands at less than 5% market share. That's why I think that we need to be thinking about regulation (like GDPR!) to change things, not expect individual users to make some kind of stand.

I mean, just look at things like this recent article that talks about building your own computer, sideloading APK files onto an Android device with a modified bootloader, and setting up your own ‘cloud’ service. It’s do-able, and I’ve done it in the past, but it’s not fun. And it’s not a sustainable solution for 99% of the population.

Source: TechCrunch

Why it's so hard to quit Big Tech

I’m writing this on a Google Pixelbook. Earlier this evening I wiped it, fully intending to install Linux on it, and then… meh. Partly, that’s because the Pixelbook now supports Linux apps in a sandboxed environment (which is great!) but mostly because using ChromeOS on decent hardware is just a lovely user experience.

Writing for TechCrunch, Danny Crichton writes:

Privacy advocates will tell you that the lack of a wide boycott against Google and particularly Facebook is symptomatic of a lack of information: if people really understood what was happening with their data, they would galvanize immediately for other platforms. Indeed, this is the very foundation for the GDPR policy in Europe: users should have a choice about how their data is used, and be fully-informed on its uses in order to make the right decision for them.This is true for all kinds of things. If people only knew about the real cost of Brexit, about what Donald Trump was really like, about the facts of global warning... and on, and on.

I think it’s interesting to compare climate change and Big Tech. We all know that we should probably change our actions, but the symptoms only affect us directly very occasionally. I’m just pleased that I’ve been able to stay off Facebook for the last nine years…

Alternatives exist for every feature and app offered by these companies, and they are not hard to find. You can use Signal for chatting, DuckDuckGo for search, FastMail for email, 500px or Flickr for photos, and on and on. Far from being shameless clones of their competitors, in many cases these products are even superior to their originals, with better designs and novel features.It's not good enough just to create a moral choice and talk about privacy. Just look at the Firefox web browser from Mozilla, which now stands at less than 5% market share. That's why I think that we need to be thinking about regulation (like GDPR!) to change things, not expect individual users to make some kind of stand.

I mean, just look at things like this recent article that talks about building your own computer, sideloading APK files onto an Android device with a modified bootloader, and setting up your own ‘cloud’ service. It’s do-able, and I’ve done it in the past, but it’s not fun. And it’s not a sustainable solution for 99% of the population.

Source: TechCrunch

Let's (not) let children get bored again

Is boredom a good thing? Is there a direct link between having nothing to do and being creative? I’m not sure. Pamela Paul, writing in The New York Times, certainly thinks so:

Paul doesn't give any evidence beyond anecdote for boredom being 'good for you'. She gives a post hoc argument stating that because someone's creative life came after (what they remembered as) a childhood punctuated by boredom, the boredom must have caused the creativity.[B]oredom is something to experience rather than hastily swipe away. And not as some kind of cruel Victorian conditioning, recommended because it’s awful and toughens you up. Despite the lesson most adults learned growing up — boredom is for boring people — boredom is useful. It’s good for you.

I don’t think that’s true at all. You need space to be creative, but that space isn’t physical, it’s mental. You can carve it out in any situation, whether that’s while watching a TV programme or staring out of a window.

For me, the elephant in the room here is the art of parenting. Not a week goes by without the media beating up parents for not doing a good enough job. This is particularly true of the bizarre concept of ‘screentime’ (something that Ian O’Byrne and Kristen Turner are investigating as part of a new project).

In the article, Paul admits that previous generations ‘underparented’. However, in her article she creates a false dichotomy between that and ‘relentless’ modern helicopter parents. Where’s the happy medium that most of us inhabit?

So parents who provide for their children by enrolling them in classes and activities to explore and develop their talents are somehow doing them a disservice? I don't get it. Fair enough if they're forcing them into those activities, but I don't know too many parents who are doing that.Only a few short decades ago, during the lost age of underparenting, grown-ups thought a certain amount of boredom was appropriate. And children came to appreciate their empty agendas. In an interview with GQ magazine, Lin-Manuel Miranda credited his unattended afternoons with fostering inspiration. “Because there is nothing better to spur creativity than a blank page or an empty bedroom,” he said.

Nowadays, subjecting a child to such inactivity is viewed as a dereliction of parental duty. In a much-read story in The Times, “The Relentlessness of Modern Parenting,” Claire Cain Miller cited a recent study that found that regardless of class, income or race, parents believed that “children who were bored after school should be enrolled in extracurricular activities, and that parents who were busy should stop their task and draw with their children if asked.”

Ultimately, Paul and I have very different expectations and experiences of adult life. I don’t expect to be bored whether at work our out of it. There’s so much to do in the world, online and offline, that I don’t particularly get the fetishisation of boredom. To me, as soon as someone uses the word ‘realistic’, they’ve lost the argument:

No, perhaps we should make more engaging, and provide more than bullshit jobs. Perhaps we should seek out interesting things ourselves, so that our children do likewise?But surely teaching children to endure boredom rather than ratcheting up the entertainment will prepare them for a more realistic future, one that doesn’t raise false expectations of what work or life itself actually entails. One day, even in a job they otherwise love, our kids may have to spend an entire day answering Friday’s leftover email. They may have to check spreadsheets. Or assist robots at a vast internet-ready warehouse.

This sounds boring, you might conclude. It sounds like work, and it sounds like life. Perhaps we should get used to it again, and use it to our benefit. Perhaps in an incessant, up-the-ante world, we could do with a little less excitement.

Source: The New York Times

The robot economy and social-emotional skills

Ben Williamson writes:

The steady shift of the knowledge economy into a robot economy, characterized by machine learning, artificial intelligence, automation and data analytics, is now bringing about changes in the ways that many influential organizations conceptualize education moving towards the 2020s. Although this is not an epochal or decisive shift in economic conditions, but rather a slow metamorphosis involving machine intelligence in the production of capital, it is bringing about fresh concerns with rethinking the purposes and aims of education as global competition is increasingly linked to robot capital rather than human capital alone.A plethora of reports and pronouncements by 'thought-leaders' and think tanks warn us about a medium-term future where jobs are 'under threat'. This has a concomitant impact on education:

The first is that education needs to de-emphasize rote skills of the kind that are easy for computers to replace and stress instead more digital upskilling, coding and computer science. The second is that humans must be educated to do things that computerization cannot replace, particularly by upgrading their ‘social-emotional skills’.A few years ago, I remember asking someone who ran different types of coding bootcamps which would be best approach for me. Somewhat conspiratorially, he told me that I didn't need to learn to code, I just needed to learn how to manage those who do the coding. As robots and AI become more sophisticated and can write their own programs, I suspect this 'management' will include non-human actors.

Of all of the things I’ve had to learn for and during my (so-called) career, the hardest has been gaining the social-emotional skills to work remotely. This isn’t an easy thing to unpack, especially when we’re all encouraged to have a ‘mission’ in life and to be emotionally invested in our work.

Williams notes:

The OECD’s Andreas Schleicher is especially explicit about the perceived strategic importance of cultivating social-emotional skills to work with artificial intelligence, writing that ‘the kinds of things that are easy to teach have become easy to digitise and automate. The future is about pairing the artificial intelligence of computers with the cognitive, social and emotional skills, and values of human beings’.I’m less bothered about Schleicher’s link between social-emotional skills and the robot economy. I reckon that, no matter what time period you live in, there are knowledge and skills you need to be successful when interacting with other human beings.Moreover, he casts this in clearly economic terms, noting that ‘humans are in danger of losing their economic value, as biological and computer engineering make many forms of human activity redundant and decouple intelligence from consciousness’. As such, human emotional intelligence is seen as complementary to computerized artificial intelligence, as both possess complementary economic value. Indeed, by pairing human and machine intelligence, economic potential would be maximized.

[…]

The keywords of the knowledge economy have been replaced by the keywords of the robot economy. Even if robotization does not pose an immediate threat to the future jobs and labour market prospects of students today, education systems are being pressured to change in anticipation of this economic transformation.

That being said, there are ways of interacting with machines that are important to learn to get ahead. I stand by what I said in 2013 about the importance of including computational thinking in school curricula. To me, education is about producing healthy, engaged citizens. They need to understand the world around them, be (digitally) confident in it, and have the conceptual tools to be able to problem-solve.

Source: Code Acts in Education

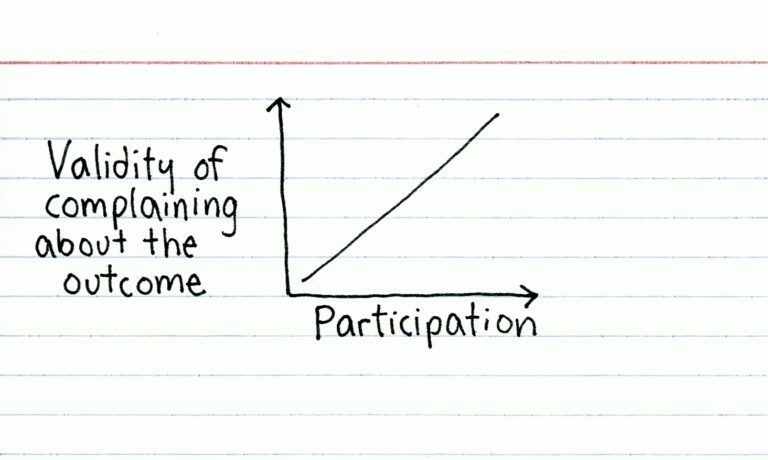

At the end of the day, everything in life is a 'group project'

I like to surround myself with doers, people who are happy, like me, to roll their sleeves up and get stuff done. Unfortunately, there’s plenty of people in life who seem to busy themselves with putting up roadblocks and finding ways why their participation isn’t possible.

Source: Indexed

Make art, tell a story

As detailed here, our co-op decided last week to lift our sights, expand our vision, and represent ourselves more holistically.

So when I stumbled upon Paul Jarvis' post on the importance of making art, it really chimed with me:

What makes the content you create awesome is that it’s a story told through your unique lens. It’s you, telling a story. It’s you not giving a fuck about anything but telling that story. It doesn’t matter if it’s a blog post about banking software or a video on how to make nut milk, the content will be better if you let your real personality shine.He gives some specific tips in the short post, which is definitely worth your time.

From my point of view with Thought Shrapnel, I don’t track open rates, etc. because it means I can focus on what I’m interested in, rather than whatever I can get people to click on.

Source: Paul Jarvis

Make art, tell a story

As detailed here, our co-op decided last week to lift our sights, expand our vision, and represent ourselves more holistically.

So when I stumbled upon Paul Jarvis' post on the importance of making art, it really chimed with me:

What makes the content you create awesome is that it’s a story told through your unique lens. It’s you, telling a story. It’s you not giving a fuck about anything but telling that story. It doesn’t matter if it’s a blog post about banking software or a video on how to make nut milk, the content will be better if you let your real personality shine.He gives some specific tips in the short post, which is definitely worth your time.

From my point of view with Thought Shrapnel, I don’t track open rates, etc. because it means I can focus on what I’m interested in, rather than whatever I can get people to click on.

Source: Paul Jarvis

Fun smartphone-based party games

At our co-op meetup last week, once we’d got business out of the way for the day, we decided to play some games. Bryan’s got a projector in his living room which he can hook up to his laptop, and he invited us all to create a Kahoot! quiz. We then played each others' quizzes, which was fun.

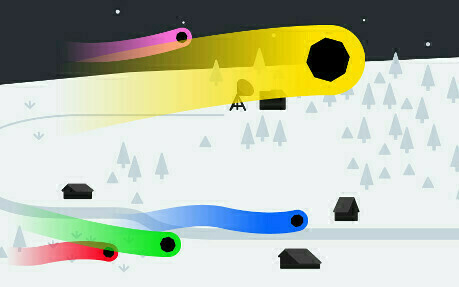

Back at home, I’d already introduced my two children to AirConsole, which they use to play games using their tablets as controllers. I searched for games we could play on the big screen without having to download anything and the first one we played was called Multeor. This involves each player controlling a ‘meteor’ which destroys things to collect points.

A list I found on Reddit was also useful, although some of them are games that have to be purchased via the Steam marketplace. We played Spaceteam which, appropriately enough for our meetup describes itself as “a cooperative shouting game for phones and tablets”. It didn’t require the project, and was great fun. I even played it with my wife when I got home!

While I’m on the subject of games, Laura introduced me to Paddle Force, which our former Mozilla colleagues Bobby Richter and Luke Pacholski created. It’s like Pong on steroids, and my children love it! Luke’s also created Pixel Drift, which reminds me a lot of playing Super Off Road at the arcades as a kid!

Fun smartphone-based party games

At our co-op meetup last week, once we’d got business out of the way for the day, we decided to play some games. Bryan’s got a projector in his living room which he can hook up to his laptop, and he invited us all to create a Kahoot! quiz. We then played each others' quizzes, which was fun.

Back at home, I’d already introduced my two children to AirConsole, which they use to play games using their tablets as controllers. I searched for games we could play on the big screen without having to download anything and the first one we played was called Multeor. This involves each player controlling a ‘meteor’ which destroys things to collect points.

A list I found on Reddit was also useful, although some of them are games that have to be purchased via the Steam marketplace. We played Spaceteam which, appropriately enough for our meetup describes itself as “a cooperative shouting game for phones and tablets”. It didn’t require the project, and was great fun. I even played it with my wife when I got home!

While I’m on the subject of games, Laura introduced me to Paddle Force, which our former Mozilla colleagues Bobby Richter and Luke Pacholski created. It’s like Pong on steroids, and my children love it! Luke’s also created Pixel Drift, which reminds me a lot of playing Super Off Road at the arcades as a kid!

Cal Newport on the dangers of 'techno-maximalism'

I have to say that I was not expecting to enjoy Cal Newport’s book Deep Work when I read it a couple of years ago. As someone who’s always been fascinated by technology, and who has spent most of his career working in and around it, I assume it was going to contain the approach of a Luddite working in his academic ivory tower.

It turns out I was completely wrong in this assumption, and the book was one of the best I read in 2017. Newport is back with a new book that I’ve eagerly pre-ordered called Digital Minimalism: On Living Better with Less Technology. It comes out next week. Again, the title is something that would usually be off-putting to me, but it’s hard to argue about the points that he makes in his blog posts since Deep Work.

As you would expect with a new book coming out, Newport is doing the rounds of interviews. In one with GQ magazine, he talks about the dangers of ‘digital maximalism’, which he defines in the following way:

The basic idea is that technological innovations can bring value and convenience into your life. So, you assess new technological tools with respect to what value or convenience it can bring into your life. And if you can find one, then the conclusion is, "If I can afford it, I should probably have this." It just looks at the positives. And it's view is "more is better than less," because more things that bring you benefits means more total benefits. This is what maximalism is: "If there's something that brings value, you should get it."That type of thinking is dangerous, as:

We see these tools, and we have this narrative that, "You can do this on Facebook," or "This new feature on this device means you can do this, which would be convenient." What you don't factor in is, "Okay, well what's the cost in terms of my time attention required to have this device in my life?" Facebook might have some particular thing that's valuable, but then you have the average U.S. user spending something like 50 minutes a day on Facebook products. That's actually a pretty big [amount of life] that you're now trading in order to get whatever the potential small benefit is.Newport calls for a new philosophy of technology which includes things like ‘digital minimalism’ (the subject of his new book):[Maximalism] ignores the opportunity cost. And as Thoreau pointed out hundreds of years ago, it’s actually in the opportunity cost that all the interesting math happens.

Digital minimalism is a clear philosophy: you figure out what's valuable to you. For each of these things you say, "What's the best way I need to use technology to support that value?" And then you happily miss out on everything else. It's about additively building up a digital life from scratch to be very specifically, intentionally designed to make your life much better.I’ve never really the type of person to go to a book club, but what with this coming out and Company of One by Paul Jarvis arriving yesterday, perhaps I need to set up a virtual one?There might be other philosophies, just like in health in fitness. More important to me than everyone becoming a digital minimalist, is people in general getting used to this idea that, “I have a philosophy that’s really clear and grounded in my values that tells me how I approach technology.” Moving past this ad-hoc stage of like, “Whatever, I just kind of signed up for maximalist stage,” and into something a little bit more intentional.

Source: GQ

Staying for nothing and shrinking from nothing (quote)

“If you do the task before you always adhering to strict reason with zeal and energy and yet with humanity, disregarding all lesser ends and keeping the divinity within you pure and upright, as though you were even now faced with its recall — if you hold steadily to this, staying for nothing and shrinking from nothing, only seeking in each passing action a conformity with nature and in each word and utterance a fearless truthfulness, then shall the good life be yours. And from this course no man has the power to hold you back.”

(Marcus Aurelius)

Through the looking-glass

Earlier this month, George Dyson, historian of technology and author of books including Darwin Among the Machines, published an article at Edge.org.

In it, he cites Childhood’s End, a story by Arthur C. Clarke in which benevolent overlords arrive on earth. “It does not end well”, he says. There’s lots of scaremongering in the world at the moment and, indeed, some people have said for a few years now that software is eating the world.

Dyson comments:

The genius — sometimes deliberate, sometimes accidental — of the enterprises now on such a steep ascent is that they have found their way through the looking-glass and emerged as something else. Their models are no longer models. The search engine is no longer a model of human knowledge, it is human knowledge. What began as a mapping of human meaning now defines human meaning, and has begun to control, rather than simply catalog or index, human thought. No one is at the controls. If enough drivers subscribe to a real-time map, traffic is controlled, with no central model except the traffic itself. The successful social network is no longer a model of the social graph, it is the social graph. This is why it is a winner-take-all game. Governments, with an allegiance to antiquated models and control systems, are being left behind.

I think that’s an insightful point: human knowledge is seen to be that indexed by Google, friendships are mediated by Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and to some extent what possible/desirable/interesting is dictated to us rather than originating from us.

We imagine that individuals, or individual algorithms, are still behind the curtain somewhere, in control. We are fooling ourselves. The new gatekeepers, by controlling the flow of information, rule a growing sector of the world.What deserves our full attention is not the success of a few companies that have harnessed the powers of hybrid analog/digital computing, but what is happening as these powers escape into the wild and consume the rest of the world

Indeed. We need to raise our sights a little here and start asking governments to use their dwindling powers to break up mega corporations before Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook are too powerful to stop. However, given how enmeshed they are in everyday life, I’m not sure at this point it’s reasonable to ask the general population to stop using their products and services.

Source: Edge.org

Surfacing popular Google Sheets to create simple web apps

I was struck by the huge potential impact of this idea from Marcel van Remmerden:

Here is a simple but efficient way to spot Enterprise Software ideas — just look at what Excel sheets are being circulated over emails inside any organization. Every single Excel sheet is a billion-dollar enterprise software business waiting to happen.I searched "google sheet" education and "google sheet" learning on Twitter just now and, within about 30 seconds found:

…and:

…and:

These are all examples of things that could (and perhaps should) be simple web apps.In the article, van Remmerden explains how he created a website based on someone else’s Google Sheet (with full attribution) and started generating revenue.

It’s a little-known fact outside the world of developers that Google Sheets can serve as a very simple database for web applications. So if you’ve got an awkward web-based spreadsheet that’s being used by lots of people in your organisation, maybe it’s time to productise it?

Source: Marcel van Remmerden