Solarpunk and five climate futures

In this interview with Andrew Dana Hudson, he lays out a brief overview of the five futures he discusses in his book. This, in turn, is based on his Masters thesis.

There’s a lot of optimism in solarpunk approaches to the future, which is attractive. We just need to have the will to realise that it’s not already over.

There is a very optimistic sustainable scenario, full of community and open-hearted kindness and capitalist power fading to a bad memory. But there’s also a scenario of overclocked consumerism, another of neo-feudal inequality, and a third of persistent military conflict and global breakdown. And a middle-of-the-road scenario in which, like today, we slowly make some progress but never, ever enough.Source: Our Shared Storm: An Interview with Andrew Dana Hudson – Solarpunk Magazine[…]

Solarpunk also seems to me a bridge toward a future of energy abundance. It’s funny, given how much solarpunk is (wonderfully) influenced by crusty degrowthers and permacultural downshifters, but it’s possible that if we keep building renewables the way we’re projected to over the next decade or so, we might end up with access to way more energy than human beings have ever had to work with (at least during the day). What do we do with that? Those electrons have to go somewhere. Well, we’ll need a lot of energy to remove a Lake Michigan’s worth of carbon out of the atmosphere, in order to stabilize the climate and roll back ocean acidification. Call that Big Chemistry. But probably there’s room for Big Computation and Big Culture as well. If solar energy becomes cheaper than free, how does that broaden our artistic ambitions? And what does that sometimes-post-scarcity mindset mean for how we treat each other?

If you believe it's over, maybe it will be

A few weeks ago, I linked to Nesta’s predictions for 2022. One of them, climate inactivism, is a form of nihilism and helplessness I also see in relation to the current war in Ukraine.

The historian in me knows that nothing is inevitable. But it’s hard to feel that one has any ability to shape or contribute to things that require aligned geopolitical will — especially while slowly crawling out of a pandemic bunker.

Just about everyone these days is a grumpy old man, obsessed with decline and convinced of its inevitable loom. More than that, the acolytes of this cult, who are everywhere, are deeply suspicious that anything could ever be as good again. The problem with the cult of decline is that it presupposes a certain fixed point of view... and is deliberately blind to all others.Source: Thankfully, Everything is Doomed | Rick Wayne[…]

From the point of view of a barnacle, the whole of the ocean seems to rise and fall. Stand long enough before the tides and eventually you’ll see the erosion of the shore. But what are the tides from inside the ocean? The erosion of one beach leads to its deposition elsewhere. What is decline but the birth of something new?

The cult of decline worships a tautology, a cognitive bias, a bank run. If you believe things are failing, then you won’t expend the energy necessary to sustain them, and they will fail. In a universe like ours, dominated by the Second Law of Thermodynamics, some creative vitality is necessary to sustain anything, even a good mood.

The Roman Empire didn’t succumb to insurmountable tidal forces. There was no tsunami of decrepitude that wiped it away. Everything it faced at the end—wars, barbarians, epidemics—was something it had conquered at least twice before. The difference was that its people no longer cared enough to overcome them. They believed it was over, and so it was.

Challenging capitalism through co-ops and community

The glossy Instagram lifestyle is actually led by a fraction of a fraction of 1% of the world’s population. Instead of us all elbowing each other out of the way in pursuit of that, this article points to a better solution: co-operation.

There are two types of economics active in the world right now — which basically means two radically divergent varieties of economic life. The first is economics as most economists and writers see it and talk about it. The second is economics as most people live it.Source: Co-ops And Community Challenge Capitalism | NoemaCall the first “the top-up.” It’s the economics of competition and asymmetrical knowledge and shareholder value and creative destruction. It’s the dominant system. We know all about the top-up. Tales of the doings of the top-up economy are mainlined into our brains from business articles, financial analysis, stories about our planet’s richest people or corporations or nations. Bezos. Buffett. Gates. Musk. Zuckerberg. The Forbes 400. The Fortune 500. The Nasdaq. The Nikkei. On and on.

Call the second “the bottom-down.” We don’t hear as much about it because it’s a lot less sexy and a lot more sticky. It involves survival mechanisms and community solidarity and cash-in-hand calculations.

But it’s the economic system of the global majority, and this makes it the more important of the two.

[…]

The top-up economic sphere functions like a gated community in which people who have money can pretend that everything they do and have in life is based on merit, and that the communal and cooperative boosts from which they profit are nothing but natural outgrowths of that merit.

[…]

Change always comes from below — and it is in the bottom-down relationships where growth and egalitarianism can flourish. Every volunteer fire department is a community platform. Every mutually managed water system demonstrates that neighbors can build things when they need each other. Every community-based childcare network or parent-teacher association is a nascent collective. Every civic association, neighborhood or church council, social action network or food pantry gives people a broader perspective. Every collectively run savings and credit association demonstrates that communal trust can give people a leg up.

Some fairy tales may be 6,000 years old

It’s fascinating to think that children’s stories may have been told and re-told across languages and cultures for millennia. It just goes to show the power of narrative structure!

Fairy tales are transmitted through language, and the shoots and branches of the Indo-European language tree are well-defined, so the scientists could trace a tale's history back up the tree—and thus back in time. If both Slavic languages and Celtic languages had a version of Jack and the Beanstalk (and the analysis revealed they might), for example, chances are the story can be traced back to the "last common ancestor." That would be the Proto-Western-Indo-Europeans from whom both lineages split at least 6800 years ago. The approach mirrors how an evolutionary biologist might conclude that two species came from a common ancestor if their genes both contain the same mutation not found in other modern animals.Source: Some fairy tales may be 6000 years old | AAAS[…]

Tehrani says that the successful fairy tales may persist because they’re “minimally counterintuitive narratives.” That means they all contain some cognitively dissonant elements—like fantastic creatures or magic—but are mostly easy to comprehend. Beauty and the Beast, for example, contains a man who has been magically transformed into a hideous creature, but it also tells a simple story about family, romance, and not judging people based on appearance. The fantasy makes these tales stand out, but the ordinary elements make them easy to understand and remember. This combination of strange, but not too strange, Tehrani says, may be the key to their persistence across millennia.

A weird tip for weight loss

Hacker News isn’t just a great resource for tech-related news. The ‘Ask HN’ threads can also be a wonderful source of information or just provide different ways of thinking about the world.

In this example, the top-voted answer to a question about weight loss had me thinking about gut bacteria ‘craving’ sugar. Weird, but a useful framing.

This is a weird tip I think I could only share with the hacker news crowd. Once I learned about gut bacteria I started thinking of my cravings as something external to me. Like instead of saying "I'm hungry and I'm in the mood for something sweet" I would realize "the hormone ghrelin is sending hunger signals to my brain and the gut bacteria in my body is asking for something that's not actually in my best interest." Being able to emotionally distance myself from my feelings let me make decisions that I knew were better for me.Source: Ask HN: Any weird tips for weight loss? | Hacker News

The week as an human construct

This article in Aeon was published at around the same time as I published a post on my personal blog about time as a human construct. In that post, I talked about the French Republican calendar and the link between it and the weather.

What’s interesting in this article is that the author, David Henkin, a history professor, talks about the success of the week as being because it’s not attached to religious, cultural, or climatological norms.

Weeks serve as powerful mnemonic anchors because they are fundamentally artificial. Unlike days, months and years, all of which track, approximate, mimic or at least allude to some natural process (with hours, minutes and seconds representing neat fractions of those larger units), the week finds its foundation entirely in history. To say ‘today is Tuesday’ is to make a claim about the past rather than about the stars or the tides or the weather. We are asserting that a certain number of days, reckoned by uninterrupted counts of seven, separate today from some earlier moment.Source: How we came to depend on the week despite its artificiality | Aeon[…]

The modern week has superimposed upon the ancient week a rhythm that is fundamentally social, incorporating an awareness of the demands and constraints of other people. Yet the modern week is also somewhat individualised, inasmuch as its rhythms are shaped by all sorts of private decisions we make, especially as consumers. Whereas Sabbath counts and astrological dominions subject everyone to the same schedule, the modern week makes us aware of our relationship to our networks and to the habits of others, while simultaneously highlighting the variety of our networks and the contingency of those habits.

The Un-Grammable Hang Zone

Instagram has never been a place I’ve ever wanted to spend any time or attention. But its impact on physical spaces is undeniable.

This post (newsletter issue?) by Drew Austin cites a couple of other authors who perfectly skewer the Instagram aesthetic as being a grammar that quickly conveys that somebody… did a thing.

The Blackbird Spyplane newsletter recently made a valuable contribution to the pantheon of essays about how the internet has transformed the physical world: a hopeful manifesto in praise of the “Un-Grammable Hang Zone,” the definition of which will be obvious if you’ve spent enough time in the Instagram-optimized settings that have proliferated in cities during the past decade—places that BBSP describes as a “high-efficiency, low-humanity kind of eatery where you point yr phone at a QR code and do contactless payment before eating a room-temp grain bowl under a pink neon sign that says ‘Living My Best Life’ in cursive.”Source: #178: I Can See It (But I Can’t Feel It) | Kneeling Bus[…]

Affirming the interchangeability of “millennial” and “Instragrammable” as descriptors, Fischer pinpoints the force that really drives them: Instagrammable “does not mean ‘beautiful’ or even quite ‘photogenic’; it means something more like ‘readable.’ The viewer could scroll past an image and still grasp its meaning, e.g., ‘I saw fireworks,’ ‘I am on vacation,’ or ‘I have friends.’” If Instagram as a medium demands readability, in other words, it puts pressure on the physical environment to simplify itself accordingly, at least in the long run.

A hardwired obedience to the capitalist system that we exist within

I’m not sure where I came across this, but Ian Nesbitt is undertaking a modern pilgrimage on a recently-uncovered medieval route from Southampton to Canterbury.

He talks about the ‘inner journey’ as well as the actual one-foot-in-front-of-another journey. Sounds interesting, so I’ve added his blog to my feed reader.

Then there was a pandemic. During that period, Iike many others, I found myself looking inwards and, in the relative stasis of those months, began to question parts of myself that I never questioned before, in particular the drive to progress and keep moving on to the next thing, to keep producing. I began to wonder if that wasn’t just part of my character, so to speak, but actually a hardwired obedience to the capitalist system that we exist within.Source: Pilgrimage #1: the adequate step | The Book of Visions

What if I never change?

Oliver Burkeman on Jocelyn K. Glei’s Hurrry Slowly is an absolute treat. In particular, he quotes Jim Benson on how we can easily become “a limitless reservoir for other people’s expectations”. I also liked the discussion around the “internalised capitalism” of “clock time”.

The title comes from an important point that Burkeman makes about so many of our hopes and dreams being based on somehow in the future being a radically different person to who we are now.

It reminded me of a section in Alain de Botton’s The Art of Travel in which he summarises Seneca by saying that the problem about going somewhere to escape things is that you always take yourself (and your mental/emotional baggage) with you…

Oliver Burkeman on why we try to control time, how perfectionism holds us back, and the problems with a “when-i-finally” mindset.Source: Oliver Burkeman: What if I never change? | Hurry Slowly

Switching from Telegram to Signal

Like many people in a relationship, I have a persistent backchannel with my wife. I have never used WhatsApp, and so we ended up using Telegram. After reading this article from the EFF, an organisation I donate to on a monthly basis, we’ve switched to Signal.

My wife’s family moved to Signal after one of the privacy debacles around data sharing between WhatsApp and Facebook. Many people I know have switched from Telegram to Matrix for group chat.

So the only people left on Telegram that I contact regularly are my parents, my sister, and a few random people I probably haven’t messaged for a while…

Source: Telegram Harm Reduction for Users in Russia and Ukraine | Electronic Frontier Foundation

If you do not have [Telegram’s] secret chat turned on, your chat communications can be exposed or seen just like channels and groups. If you do turn on secret chat, then Telegram cannot see the contents of your communication, but they still have access to metadata about the communications, including who you talked to and when you talked to them. It may be possible to draw very specific conclusions about what you are doing based only on the metadata about your conversation.

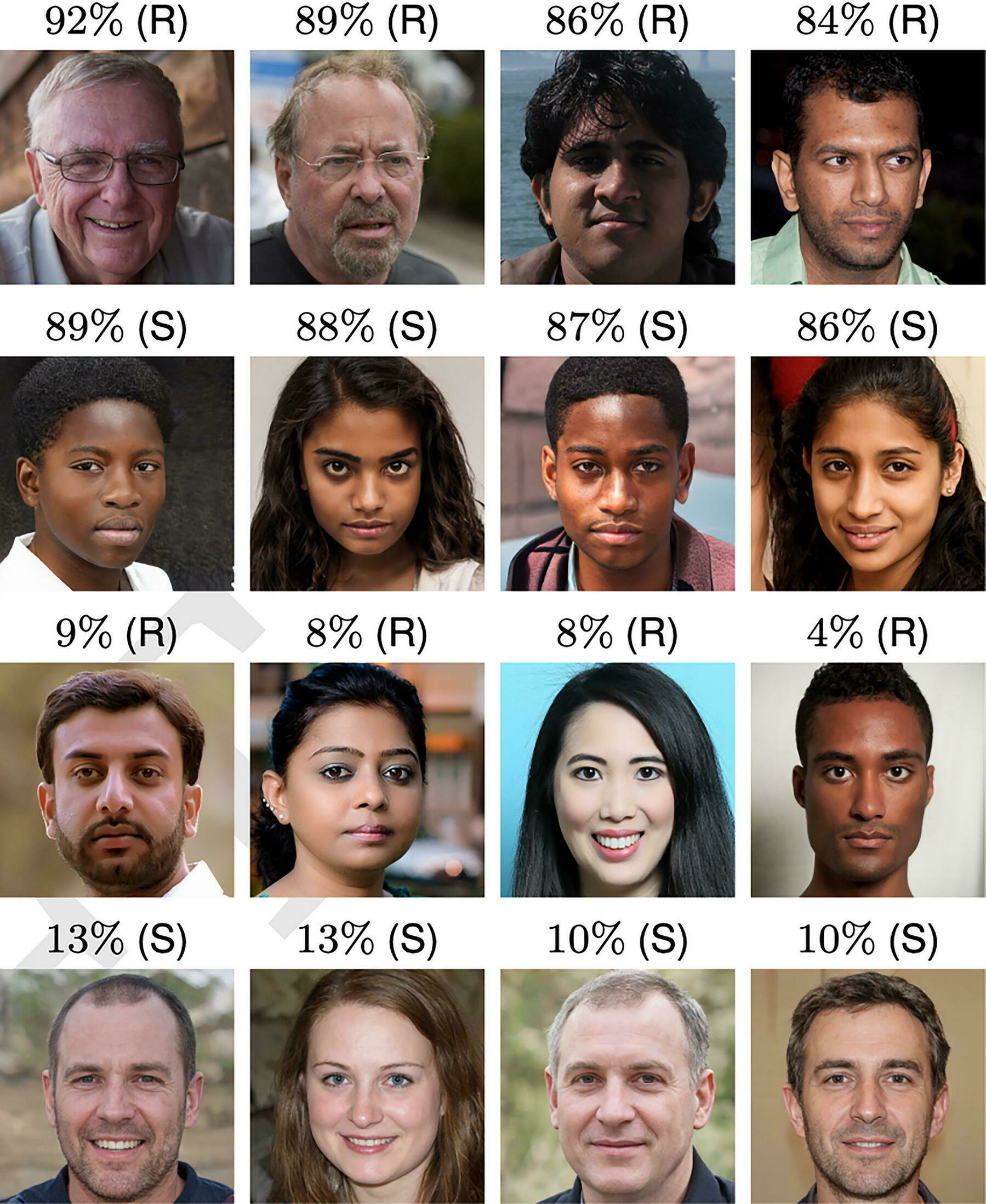

AI-synthesized faces are here to fool you

No-one who’s been paying attention should be in the last surprised that AI-synthesized faces are now so good. However, we should probably be a bit concerned that research seems to suggest that they seem to be rated as “more trustworthy” than real human faces.

The recommendations by researchers for “incorporating robust watermarks into the image and video synthesis networks” are kind of ridiculous to enforce in practice, so we need to ensure that we’re ready for the onslaught of deepfakes.

This is likely to have significant consequences by the end of this year at the latest, with everything that’s happening in the world at the moment…

Synthetically generated faces are not just highly photorealistic, they are nearly indistinguishable from real faces and are judged more trustworthy. This hyperphotorealism is consistent with recent findings. These two studies did not contain the same diversity of race and gender as ours, nor did they match the real and synthetic faces as we did to minimize the chance of inadvertent cues. While it is less surprising that White male faces are highly realistic—because these faces dominate the neural network training—we find that the realism of synthetic faces extends across race and gender. Perhaps most interestingly, we find that synthetically generated faces are more trustworthy than real faces. This may be because synthesized faces tend to look more like average faces which themselves are deemed more trustworthy. Regardless of the underlying reason, synthetically generated faces have emerged on the other side of the uncanny valley. This should be considered a success for the fields of computer graphics and vision. At the same time, easy access (https://thispersondoesnotexist.com) to such high-quality fake imagery has led and will continue to lead to various problems, including more convincing online fake profiles and—as synthetic audio and video generation continues to improve—problems of nonconsensual intimate imagery, fraud, and disinformation campaigns, with serious implications for individuals, societies, and democracies.Source: AI-synthesized faces are indistinguishable from real faces and more trustworthy | PNAS

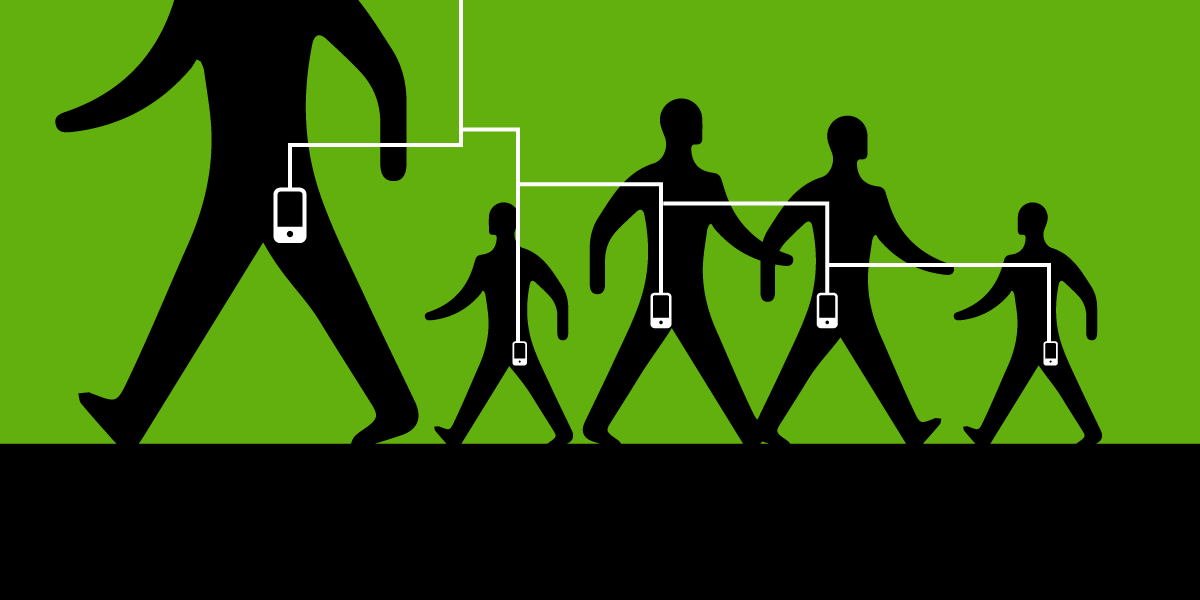

Lizard brain vs infinite scroll

It’s funny that the author of this article uses Reddit’s app as an example of the problems with infinite scroll, as it’s the app I’ve most recently deleted on my phone. I installed it because I had to in order to continue reading a particular subreddit that I needed access to, but then the front page is just, so interesting for easily-distracted people (i.e. all of us) that I had delete it a few days later.

As a parent, there are some apps I don’t allow my kids to access at all, and other ones I kind of tolerate if they access them through the browser. The combination of notifications and infinite scroll is a dangerous drug for the mind.

When I take a minute to think about the things I enjoy doing with my devices, it helps me realize that they’re the ones where I’m deliberately using it. Talking to people I know, for example. Watching that movie I had been looking forward to. Looking up the origin of an oddly spelled word. Creating, rather than just consuming, and using it as a tool to improve my life, even if that little improvement is a one word answer to a tiny question that had been bugging me.Source: My lizard brain is no match for infinite scroll | Caffeinspiration[…]

I don’t have any quick fixes or easy answers. I’ve struggled with this for a very long time. I’ve gotten much better at dealing with it, but I find I have to remain conscious of it. That’s where admitting defeat helps; I know how my brain works, and I can work with it. Let’s not install that app with the infinite scroll, since we can probably get by with just the mobile web version. Let’s not log in, unless there’s a reason you need to, since they’re after you with recommendations for your account. Let’s try to be conscious of how much time you end up spending on certain sites.

Xero starts using consent-based decision making

Sociocracy, which includes consent-based decision making, is something we use at WAO. I’ve written about it several times on my personal blog as well as here.

It looks like the approach is working not just for yogurt-knitting vegans who work in co-operatives, but hard-nose businesses like Xero. Who knew?

For the past year, I’ve been lucky enough to work on a big technology project at Xero, where I spend much of my time supporting the leadership team. But it didn’t take long for me to realise that when you have a large number of people bringing their own perspectives and opinions into a complex situation, consensus is going to be challenging (if not impossible).Source: Making better, faster decisions that are good enough for now | Bonnie SlaterSo I decided to introduce consent-based decision making to the leadership team. It’s something that a colleague introduced me to last year. It’s had such a positive impact on my work that I thought I’d share more about it, in the hope that you can use this simple technique in your team as well.

What makes writing more readable?

I had the pleasure of interviewing Georgia Bullen, Executive Director of Simply Secure yesterday. I noticed that her website links to an active RSS feed from her Instapaper account, which I immediately added to my feed reader.

My first gleaning from that feed came today, when I came across this clever website which not just explains, but shows how to make writing more readable. Highly recommended.

Technology alone isn’t the answer. Even the most thoughtful algorithms and robust data sets lack context. Ultimately, the effectiveness of plain language translations comes down to engagement with your audience. Engagement that doesn’t make assumptions about what the audience understands, but will instead ask them to find out. Engagement that’s willing to work directly with people with disabilities or limited access to education, and not through intermediaries. As disabled advocates and organizations led by disabled people have been saying all along: “Nothing about us without us.”...and the plain language version:

Source: What makes writing more readable? | pudding.cool

Audrey Watters on the technology of wellness and mis/disinformation

Audrey Watters is turning her large brain to the topic of “wellness” and, in this first article, talks about mis/disinformation. This is obviously front of mind for me given my involvement in user research for the Zappa project from Bonfire.

In February 2014, I happened to catch a couple of venture capitalists complaining about journalism on Twitter. (Honestly, you could probably pick any month or year and find the same.) “When you know about a situation, you often realize journalists don’t know that much,” one tweeted. “When you don’t know anything, you assume they’re right.” Another VC responded, “there’s a name for this and I think Murray Gell-Mann came up with it but I’m sick today and too lazy to search for it.” A journalist helpfully weighed in: “Michael Crichton called it the ”Murray Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect," providing a link to a blog with an excerpt in which Crichton explains the concept.Source: The Technology of Wellness, Part 1: What I Don't Know | Hack Education

Offline for 3 days

David Cain took three days offline. It sounds like something that wouldn’t have been amazing 15 years ago, but these days goes straight to the front page of Hacker News.

I can understand why it’s weird to live in the hybrid world of being middle-aged and being alive before everything and everyone was online. But the big thing we need to do is to help the next generations understand that there is an offline world which is rich and worthwhile.

This simplicity was disorienting in a way. Many times a day I would finish whatever activity I was doing, and realize there was nothing to do but consciously choose another activity and then do that. This is how I made my first bombshell discovery: I take out my phone every time I finish doing basically anything, knowing there will be new emails or mentions or some other dopaminergic prize to collect. I have been inserting an open-ended period of pointless dithering after every intentional task.Source: Raptitude.com – Getting Better at Being Human

Facebook is dying

While I only deleted my Twitter account at the end of last year, it’s been about 12 years since I deleted my Facebook one. As Cory Doctorow points out, it’s a terrible organisation that no-one should work for, and whose products no-one should use.

Even before its stock fell off a cliff, Facebook was mired in a multi-year hiring crisis. Nobody wanted to work for Facebook because it’s a terrible company that makes terrible products that everyone hates and only use because the company has rigged the system to punish users for switching.Source: I’ve been waiting 15 years for Facebook to die. I’m more hopeful than ever | The GuardianFacebook was already paying a wage premium, offering sweeteners to in-demand workers in exchange for checking their consciences at the door. Those sweeteners mostly took the form of shares, which means that all those morally flexible “Metamates” got a hefty pay-cut when the company’s stock price fell off a cliff. Expect a lot of them to leave – and expect the company to have to pay even more to replace them. Companies with falling share prices can’t use share grants to attract workers.

Facebook is now famously trying to pivot (ugh) to virtual reality to save itself. It’s an expensive gambit. It’s going to alienate a lot of its users. It’s going to alienate a lot of its in-demand workers. It’s going to freak out a lot of regulators.

Meanwhile, the switching costs for people who want to jump ship keep getting lower. It’s not merely that fewer and fewer of the people you want to talk with are still on Facebook. Even if there’s someone whose virtual company you can’t bear to part with, lawmakers in the US and Europe are working on legislation that would force Facebook to allow third parties to “federate” new services with it. That would mean that you could quit Facebook and join an upstart rival – say, one by a privacy-respecting nonprofit or even a user-owned co-op – and still exchange messages with the communities, customers and family you left behind on Facebook’s sinking ship.

The hard part of the work is doing the work

I am thankful every working day that I set up a co-operative with friends and former colleagues so that while I’m in control of my own destiny, I also have awesome people to work alongside.

Freelancing is like having a job without a boss (alas)Source: Common pitfalls and myths of the new economy | Seth’s BlogWell, you still have a boss. It’s you. And you might not be a good one. Freelancers spend part of their day doing the work, and the rest of the time earning better clients.

AI cannot hold copyright (yet)

I think common sense would suggest that copyright should only apply to human-created works. But the line between what human brains and artificial ones do when working together is a thin one, so I don’t think this ruling is the last word.

A Recent Entrance to Paradise is part of a series Creativity Machine produced on the subject of a near-death experience. Thaler said the work “was autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine,” according to court documents.Source: U.S. Copyright Office Rules That AI Cannot Hold Copyright | ARTnews.comThe U.S. Copyright review board said that this goes against the basic tenets of copyright law, which suggest that the work must be the product of a human mind. “Thaler must either provide evidence that the Work is the product of human authorship or convince the Office to depart from a century of copyright jurisprudence. He has done neither,” wrote the review board in its decision.

Technology and productivity

Julian Stodd’s personal realisation that what the people who make ‘productivity tools’ want and what he wants might be two different things.

See also: Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman

I fear that the suites of tools and features that allow me to work from anywhere do, in fact, distract me everywhere.Source: The Delusion of Productivity | Julian Stodd’s Learning BlogI feel that at time i have lost the art of long form and collapsed into the conversational and reactive.

[…]

Does technology always make us more productive – or can technology hold us apart? Do we need to be together to forge culture, and to find meaning, or can being together make us more busy than wise?

I suspect my personal (and perhaps our organisational) challenge is one of separation: to separate out my segregated spaces – to separate my thinking and doing, my learning and acting, my reflection and practice.