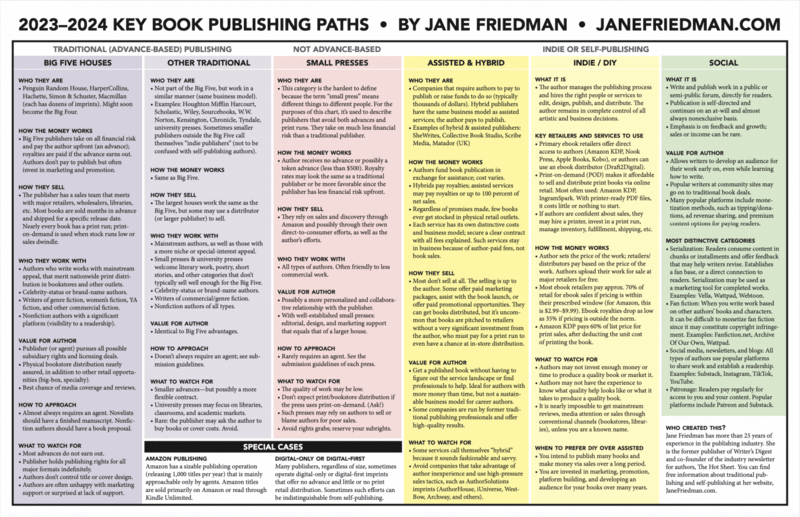

Getting your book published in 2023

This, via Warren Ellis, is a useful resource. I also like that its creator, Jane Friedman, has made it available to be downloaded, printed, and shared “no permission required” (although I wish she’d explicitly used a CC0 license)

When I shared this with a friend, they pointed out that it doesn’t include the ‘kickstarter’ kind of model. While Friedman points out that the chart is primarily for ‘trade press’ (i.e. books with a general audience) there’s a whole different type of approach, which I kind of pioneered a decade ago with OpenBeta and which is more easily achieved these days with platforms such as Leanpub.

(click on image to download PDF)

One of the biggest questions I hear from authors today: Should I traditionally publish or self-publish?Source: The Key Book Publishing Paths: 2023–2024This is an increasingly complicated question to answer because:

Thus, there is no one path or service that’s right for everyone all the time; you should take time to understand the landscape and make a decision based on long-term career goals, as well as the unique qualities of your work. Your choice should also be guided by your own personality (are you an entrepreneurial sort?) and experience as an author (do you have the slightest idea what you’re doing?).

- There are now many varieties of traditional publishing and self-publishing, with evolving models and diverse contracts.

- It’s not an either/or proposition; you can do both. Many successful authors, including myself, decide which path is best based on our goals and career level.

Good writing is good writing

I’ve seen all of the Star Wars films at least once. I’m not big into sci-fi or fantasy, but on the recommendation of seemingly everyone (including my son) I’ve started watching Andor on Disney+.

I’m not even half-way through but it really is excellent, with no ridiculously CGI, just a believable world and an excellent storyline.

Andor largely eschews many Star Wars staples, such as wacky creatures and funny droids, focusing instead on the realities of power and violence. Fantasy author Erin Lindsey, who worked for many years as a UN aid worker, found the show’s depiction of politics to be completely believable. “I think there are clearly people on the writing team who are students of spy novels like [those by] John le Carré and who are students of politics and students of history, who are really looking at how revolution has happened here on Earth and what that looks like,” she says.Source: ‘Andor’ Is a Master Class in Good Writing | WIREDDespite its high quality, Andor‘s ratings have lagged behind Star Wars shows like Obi-Wan Kenobi and The Mandalorian. Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy host David Barr Kirtley hopes that Andor will attract a larger audience in season 2. “It’s so good,” he says. “It deserves higher ratings than it’s gotten so far. And I definitely want to see more shows like this. This is the kind of show—especially the kind of Star Wars show—that I’ve been pining after for all these years. So please let’s all just give it as much support as we can.”

Update your profile photo at least every three years

I think this is good advice. I try to update mine regularly, although I did realise that last year I chose a photo that was five years old! I prefer ‘natural’ photos that are taken in family situations which I then edit, rather than headshots these days.

Unfortunately, some people will make assumptions about you based on a photo, and those impressions paint a picture of how we perceive someone. “The first thing people encounter is the delta” between how you represent yourself in a photo and how you look in person, Marion Dino, a retired human resources executive and career coach explains. “You want to convey that you are trustworthy. Most people aren’t intentionally judging, but we all have unconscious biases, and you leave yourself open to the interpretation of being less than honest if you don’t represent yourself accurately.” Most of the time, a résumé doesn’t include a profile photo, but “recruiters do look at LinkedIn and other social media platforms,” Dino says. “You don’t want to leave the impression that you aren’t authentic.”Source: How Often Should You Update Your Profile Photos? | WIRED[…]

And how often should you update your photos, so they don’t give someone pause when you meet in person? “Profile pictures should be updated every three years unless there is a significant change in appearance. Then, they should be taken sooner.” So, the next time you scroll LinkedIn, log in to a Zoom meeting, or even send an email with a thumbnail profile photo, think about how you want to be perceived, and don’t hesitate to use a picture that fully represents who you are.

Let's make private schools help pay for state schools

I’m delighted to hear about this and I hope the vote passes. It’s a farce that place of privilege should gain tax breaks and have ‘charitable status’. As I’ve said many times before, opting out of state education and the NHS should be, either impossible or ridiculously expensive.

Labour will attempt to force a binding vote on ending private schools’ tax breaks and use the £1.7bn a year raised from this to drive new teacher recruitment.Source: Labour look to force vote on ending private schools’ tax breaks | The GuardianThe motion submitted by Keir Starmer’s party for the opposition day debate on Wednesday is drafted to push the charitable status scheme that many private schools enjoy to be investigated, as the party attempts to shift the political focus on to education.

[…]

Labour will hope the motion will force the government to make its MPs vote down an issue, rather than ignoring the process. A Labour source has previously said: “Conservative MPs voting against our motion are voting against higher standards in state schools for the majority of children in our country.”

Chameleon e-ink car

Most of the things at the annual CES tech show in Las Vegas every year are either pointless (at least to me) or in some way enabling of ever-greater surveillance.

However, this e-ink car really caught my imagination. I’m a big fan of both e-ink (it’s easy on the eyes) and customisation, so this is really in my sweet spot. I did wonder for half a second about a whole movie plot using e-ink for a getaway car, and then I realised that every car these days has a GPS chip and SIM card in it…

Introduced by Arnold Schwarzenegger, BMW’s i Vision Dee caught the attention with its E-ink outer skin, which can change colour in an instant. Don’t expect that on a car you can buy any time soon but it also has a head-up display projected across the full width of the windscreen, which will be available from 2025.Source: Chameleon cars, urine scanners and other standouts from CES 2023 | The Guardian

Level 3 busy-ness

Discovered via Kottke, this ‘seven levels of busy’ makes me realise that I don’t really want to be beyond Level 3 most weeks. Level 4 is OK on occasion.

It’s over a decade since I’ve experienced Levels 5 and 6, I reckon. And I’ve never let things get to Level 7.

Level 3: SIGNIFICANT COMMITMENTS I have enough commitments that I need to keep track of them in a tool because I can no longer organically triage. My calendar is a thing I check infrequently, but I do check it to remind myself of the flavor of this particular day.Source: The Seven Levels of Busy | Rands in Repose

Photo: Dan Freeman

Nick Cave's plans for 2023

The artist Nick Cave has a (newsletter? blog?) called The Red Hand Files in which he answers questions from his fans. Somebody pointed me towards a recent post where he talks about his aim to write and record a new album in 2023.

I love the way he talks about the creative process, and how mysterious it is.

My plan for this year is to make a new record with the Bad Seeds. This is both good news and bad news. Good news because who doesn’t want a new Bad Seeds record? Bad news because I’ve got to write the bloody thing.Source: Nick Cave - The Red Hand Files - Issue #217[…]

Writing lyrics is the pits. It’s like jumping for frogs, Fred. It’s the shits. It’s the bogs. It actually hurts. It comes in spurts, but few and far between. There is something obscene about the whole affair. Like crimes that rhyme. I hope this doesn’t last long. I’m actually scared. But it always does. Last long. To write a song. You hope to God there is something left. You are bereft. I’m going to stop this letter. It isn’t making things better. It’s like flogging a dead horse. Worse. It’s a hearse. A hearse of dead verse. Dead, Fred. Dead.

Walking around like Lionel Messi

I didn’t get a chance to read this excellent article in The New Yorker about Lionel Messi until today. It was published the week leading up to the World Cup Final, which of course Argentina won, making Messi possibly the greatest player of all time (behind Pele? RIP.)

What I like about it is that it shows that ‘work’ doesn’t always look like running around the place looking ‘busy’. In fact, the greatest people at a given thing are usually involved in the background while people are concentrating solely on the foreground.

Messi is soccer’s great ambler. To keep your eyes fixed on him throughout a match is both spellbinding and deadly dull. It is also a lesson in the art and science of watching a soccer match. If you ask any astute observer—an experienced coach or player or tactically tuned-in analyst—how to understand the game, they will advise you to take your eyes off the ball. There may well be an analogous precept, with a German name, in philosophy or art history or mechanical physics. The idea is this: to apprehend the main thrust of the narrative, to really wrap your mind around what’s going on, you must shift your focus from the foreground to the background.Source: The Genius of Lionel Messi Just Walking Around | The New Yorker[…]

[I]f you happen to be watching a match featuring Leo Messi, you’ll notice that something on the order of eighty-five per cent of the time, he can be found off the ball, strolling and dawdling and looking mildly uninterested. It is the kind of behavior associated with selfish players, prima donnas who expend no effort on defense and bestir themselves only when goal-scoring opportunities arise. Messi, of course, is one of the most prolific scorers of all time, with a career total of nearly eight hundred goals in club and international competition. His penchant for walking is not a symptom of indolence or entitlement; it’s a practice that reveals supreme footballing intelligence and a commitment to the efficient expenditure of energy. Also, it’s a ruse—the greatest con job in the history of the game.

A famous aphorism, usually attributed to the Spanish manager Vicente del Bosque, sums up the subtly visionary play of the midfielder Sergio Busquets this way: when you watch the game, you don’t see Busquets—but when you watch Busquets, you see the whole game. Something related might be said about the great Argentinean: when you watch Messi, you watch him watching the game. Another manager, Manchester City’s Pep Guardiola, who coached Messi for four years at Barcelona, has described his walking, especially in the early stages of a game, as form of cartography—an exercise in scanning and surveying, taking the measure of the defense, noticing where the vulnerabilities lie, and calculating when and how opportunities might be seized. “After five, ten minutes, he’ll have a map in his eyes and in his brain,” Guardiola has said. “[He’ll] know exactly what is the space and what is the panorama.”

Spreading joy in 2023

I love the idea behind this list of 52 acts of kindness. Realistically, number 14, 16, and 38 are the ones I’m likely to do (because I already do them!)

14. Pay a compliment “You’re looking nice,” is good. “You have great skin” or “I love your shoes” is better. Someone once told me I had “cute ears” and I treasured it for years.Source: 52 acts of kindness: how to spread joy in every week of 2023 | The Guardian16. Make a mixtape Give someone a curated Spotify or YouTube playlist of stuff you think they would like.

38. Drive kindly If you’re sure it’s safe, flash your lights or wave your hand at someone waiting to cross the road in front of you.

Preparation is everything

I used to have a quotation on the wall of my classroom when I was a teacher that has been attributed to various different people, but reads: “Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work."

The point of the quotation is that to have any kind of success in life that isn’t luck-dependent, you have to be ready. That looks different depending on the situation, but (for me at least) involves thinking about different scenarios, what could play out, etc.

This post, found via HN, is from a developer thinking about software projects. But the point he makes is universal: preparing effectively means that you can get on and focus on delivering without having to keep stopping.

Motivation is the willingness to want to do something. This is of course an important first step in potentially being productive. We are better at things we want to do, rather than things we’re forced to do by others, or by our own self discipline.Source: To Be Productive, Be Prepared | Martin RueBut motivation is nothing more than that. It helps us start, but it doesn’t mean we’ll finish, or even produce half of what we want to. Even when we are motivated, if we don’t make enough progress our motivation has a way of epically [sic] disappearing.

[…]

Knowing how to make progress and making progress are two different things, but we often conflate them and treat them as the same thing. We basically jump into the task and start.

[…]

Productivity doesn’t come from feeling motivated, it comes from knowing what you need to do in enough detail that you can complete it without continually stopping and losing your focus.

Image: Brett Jordan

That was 2022

Inspired by Warren Ellis closing his LTD site until 2023, this is a notification that Thought Shrapnel is done for the year!

I may send out a 'best of the year' newsletter (sign up here!) if I don't end up in a mince pie coma, but either way thanks for your attention and appreciation. See you in January!

Image by Kelly Sikkema

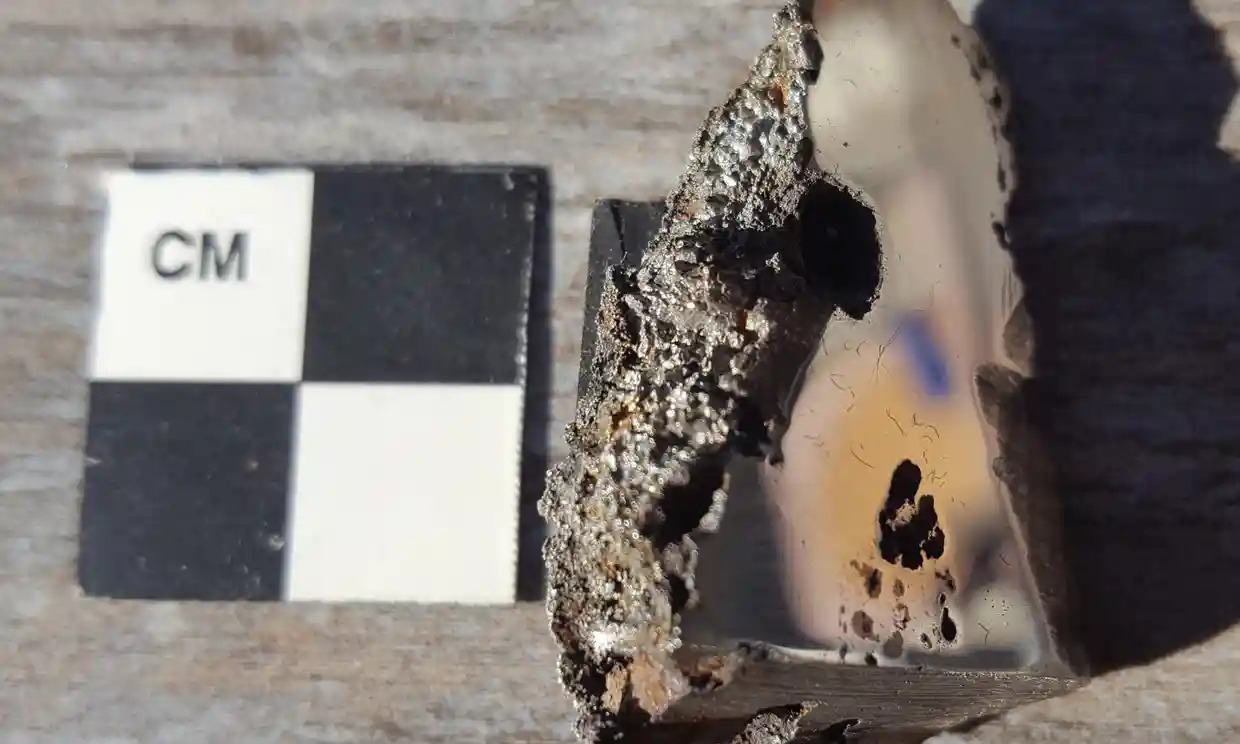

'Nightfall' meteorite contains new and unusual minerals

OK, so it’s not Vibranium, but discovering potentially three new minerals in a meteorite found in Somalia is pretty exciting! I wonder what new substances we’ll find as we further explore space, and what uses we’ll discover for them?

The meteorite, the ninth largest recorded at over 2 metres wide, was unearthed in Somalia in 2020, although local camel herders say it was well known to them for generations and named Nightfall in their songs and poems.Source: Researchers discover two new minerals on meteorite grounded in Somalia | The Guardian[…]

Dr Chris Herd, a professor in the department of earth and atmospheric sciences and the curator of the collection, said that while he was classifying the rock he noticed “unusual” minerals. Herd asked Andrew Locock, the head of the university’s electron microprobe laboratory, to investigate.

[…]

Similar minerals had been synthetically created in a lab in the 1980s but never recorded as appearing in nature, Herd said, adding that these new minerals could help understand how “nature’s laboratory” works and may have as yet unknown real-world uses. A third potentially new mineral is being analysed.

No benefits to post-Brexit deregulation

Coupled with the pandemic and the energy crisis, Brexit is absolutely destroying the UK at the moment. If you haven’t watched The Brexit Effect made by the Financial Times, then you really, really should.

This article in the New Statesman argues that the deregulation touted as a huge benefit of Brexit isn’t wanted or needed by most UK businesses. It’s the red tape added by being outside the EU single market that’s the problem.

Most businesses have no interest or understanding of the government’s plans for post-Brexit deregulation. And a majority of companies could not name a single EU law that they would change or remove to become more profitable, according to findings shared exclusively with the New Statesman by the British Chambers of Commerce.Source: Exclusive: Most UK businesses see no benefit in post-Brexit deregulation | New Statesman[…]

In a new survey of 938 businesses, made up largely of SMEs (and therefore representative of the UK economy), just 14 per cent specified an EU regulation they would remove; 58 per cent of firms had no preference over the amendment or removal of any EU regulation. Half said that deregulation is either a low priority or not a priority at all.

Study shows no link between age at getting first smartphone and mental health issues

Where we live is unusual for the UK: we have first, middle, and high schools. The knock-on effect of this in the 21st century is that kids aged nine years old are walking to school and, often, taking a smartphone with them.

This study shows that the average age children were given a phone by parents was 11.6 years old, which meshes with the ‘norm’ (I would argue) in the UK of giving kids one when they go to secondary school.

What I like about these findings are that parents overall seem to do a pretty good job. It’s been a constant battle with our eldest, who is almost 16, to be honest, but I think he’s developed some useful habits around technology.

Parents fretting over when to get their children a cell phone can take heart: A rigorous new study from Stanford Medicine did not find a meaningful association between the age at which kids received their first phones and their well-being, as measured by grades, sleep habits and depression symptoms.Source: Age that kids acquire mobile phones not linked to well-being, says Stanford Medicine study | Stanford Medicine[…]

The research team followed a group of low-income Latino children in Northern California as part of a larger project aimed to prevent childhood obesity. Little prior research has focused on technology acquisition in non-white or low-income populations, the researchers said.

The average age at which children received their first phones was 11.6 years old, with phone acquisition climbing steeply between 10.7 and 12.5 years of age, a period during which half of the children acquired their first phones. According to the researchers, the results may suggest that each family timed the decision to what they thought was best for their child.

“One possible explanation for these results is that parents are doing a good job matching their decisions to give their kids phones to their child’s and family’s needs,” Robinson said. “These results should be seen as empowering parents to do what they think is right for their family.”

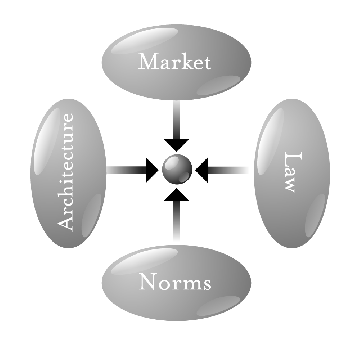

Four forces that constrain our actions

‘Pathetic Dot’ is not a great name for a theory, and the diagram on the Wikipedia page isn’t the best, but Christina Bowen reminded me of it during an introductory conversation yesterday.

I can’t find it again quickly, but this also reminds me of a discussion I saw about how credit scores can exert almost as much unseen social control over people in the West as very visible social control mechanisms in more authoritarian countries.

The pathetic dot theory or the New Chicago School theory was introduced by Lawrence Lessig in a 1998 article and popularized in his 1999 book, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace. It is a socioeconomic theory of regulation. It discusses how lives of individuals (the pathetic dots in question) are regulated by four forces: the law, social norms, the market, and architecture (technical infrastructure).Source: Pathetic dot theory | WikipediaLessig identifies four forces that constrain our actions: the law, social norms, the market, and architecture. The law threatens sanction if it is not obeyed. Social norms are enforced by the community. Markets through supply and demand set a price on various items or behaviors. The final force is the (social) architecture. By that Lessig means “features of the world, whether made, or found”; noting that facts like biology, geography, technology and others constrain our actions. Together, those four forces are the totality of what constrains our action, in fashion both direct and indirect, ex post and ex ante.

[…]

The theory can be applied to many aspects of life (such as how smoking is regulated), but it has been popularized by Lessig’s subsequent usage of it in the context of the regulation of the Internet.

French views of Brexit

It’s always interesting reading articles from foreign newspapers about the state of the UK. I wish it were true that conversations about Brexit and the damage it’s done were on the table. But I just don’t see it.

Brexit is once again at the heart of the British debate. Experts and the media are openly criticizing its negative effects on the UK economy. On the BBC's flagship politics show Question Time and on the popular LBC talk radio station, the audience is increasingly critical of the UK's divorce from the European Union. According to a poll by the YouGov institute published on November 17, 56% of respondents believe that the country "was wrong to leave the EU" on December 31, 2020.Source: Amid an economic and social crisis, anti-Brexit sentiment is growing in the UK[…]

The presentation of an austerity budget by new Prime Minister Rishi Sunak's government on November 17 in an attempt to restore the country's financial credibility (after the disastrous episode of the Liz Truss "mini-budget") has loosened tongues. On this occasion, the Office for Budget Responsibility estimated that British living standards would plummet by 7% over the next two years. This independent government body said that Brexit "has had a significant negative impact" on British foreign trade, with the decline amounting to 15% over the long term.

Who wants to live forever?

I definitely feel the middle-aged white guy urge to focus on health, nutrition, etc. But I just felt really sorry when I watched the start of a video where Bryan Johnson, who sold his company to PayPal, goes through his routine. He just looks… lonely?

Photo below is of Jack Dorsey, former Twitter CEO, who also follows an ascetic lifestyle.

Who wants to live for ever? Not me, with all due respect to Freddie Mercury for asking, and possibly not you either. Only a third of Britons even want to make it to 100, according to a recent Ipsos poll carried out for the British not-for-profit initiative the Longevity Forum. This suggests less a death wish than a fear of what growing old may actually involve. Tellingly, the older the respondent already was, the less enthusiastic they were about getting very much older. Extreme age can look brutal, up close.Source: Who wants to live to 100 on a diet of lentil and broccoli slurry? Mostly rich men | The GuardianPersonally, I want very much to live until my child no longer needs me, whenever that may be, and to enjoy some kind of retirement. But beyond that, I just want to live until it feels like enough, and then ideally to have some control over the end. I’d rather have a busy, happy, meaningful life and drop dead at 75 than make it to 150 and run out of ways to fill the endless days.

Japanese miniature dioramas

I love these so much.

Miniature Calendar is an incredible ongoing project by Japanese artist Tatsuya Tanaka, that features beautiful miniature dioramas of everyday life using common household objects such as food, cloth, stationery, electronic devices, and even masks.Source: Japanese Artist Creates Amazing Miniature Dioramas Every Day For 10 Years | Digital Synopsis

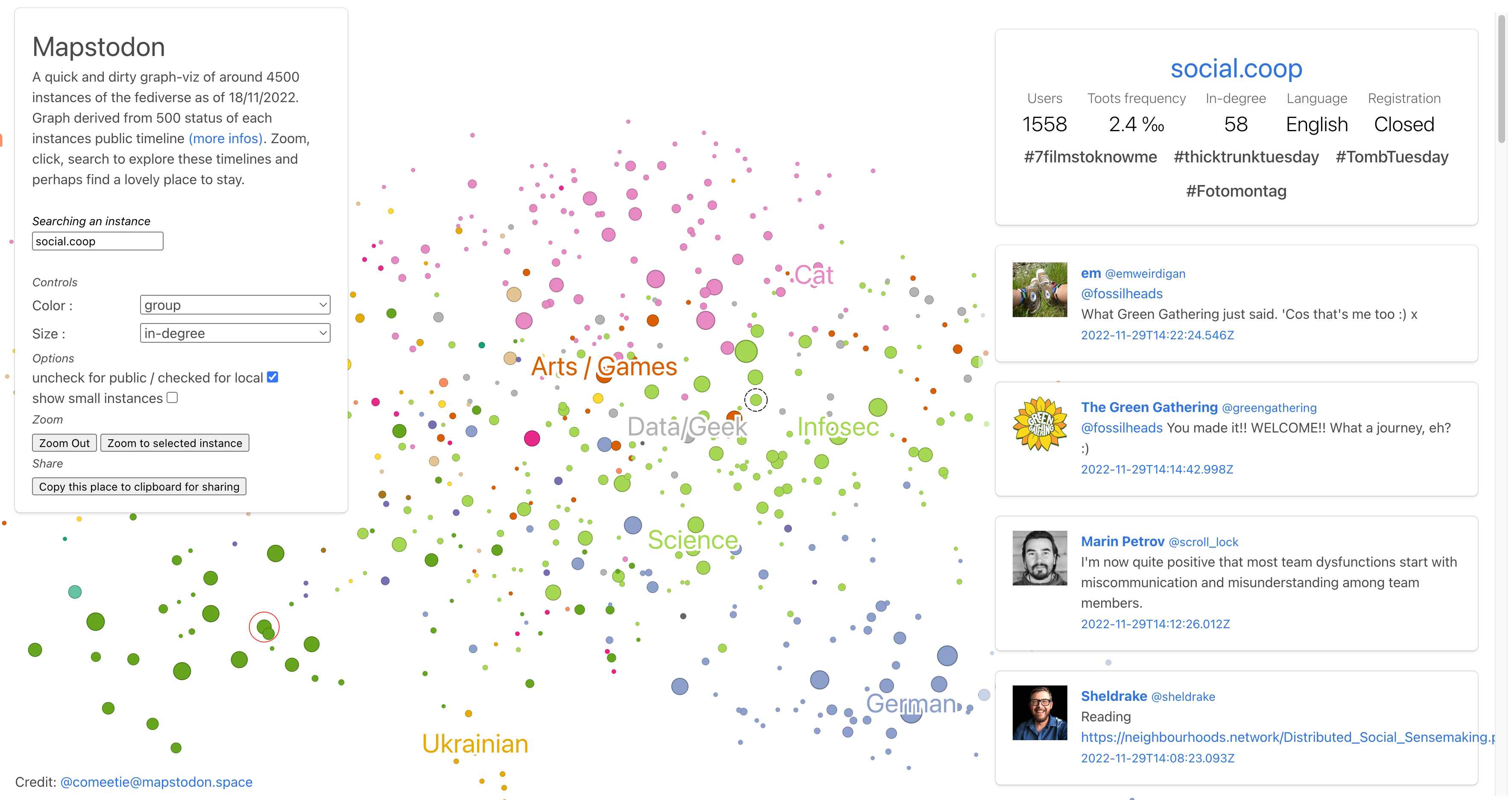

(Partially) visualising the Fediverse

About a decade ago, it was possible to visualise your LinkedIn network. I really liked it, especially as I had three distinct groups of connections (EdTech, schools, and Higher Ed).

This website allows you to visualise around 4.5k Fediverse instances, as of last week. You can change the colour and size of the dots depending on number of users, posts, theme, etc.

Exercise.cafe isn’t on there, nor is wao.wtf. But it’s still a useful tool.

Source: Mapstodon