Visual music discovery

I’ve got an upcoming interview for a BBC R&D research role and so have been looking at what they’ve been up to recently. As part of that, I came across an experiment called ‘Orbit’ which is a visual way of discovering new music based on listening to audio snippets.

Find 5 new tracks every day from undiscovered artists

Source: Orbit

The Australian ban on social media is probably unworkable

This post by Neil Brown is a couple of years old now, but he linked to it in the wake of news that the Australian government have announced a ban on social media for under-16s.

As he points out by going through examples, this is entirely unworkable. When I tried to explain this to someone less technical, I realised that unless you enforce biometrics at every login, it’s pretty much impossible to enforce in a good-faith way. And that would be a huge privacy violation of children.

Let’s say that there a multiple countries with similar-but-not-identical laws.

Country A, which says that the website operator is not to provide its service to people in Country A who are under 21.

Country B, which says that the website operator is not to provide its service to people in Country B who are under 25.

And Country C, which says that the website operator is not to provide its service to people in Country C at all.

Assuming that the website operator does not want to shut up shop totally - by applying the most restrictive rule, of Country C, to everyone - and that it does care about the laws in other countries (a big “if”, but it’s my example, so…) how does the website operator establish where the user is located at the point at which they access the site, to know which rule to apply?

tl;dr

I don’t think you can, with any reasonable degree of assurance.

Source: Neil’s blog

Image: julien Tromeur

AI identifies more Nazca Lines

A great use for machine learning in finding, and hopefully helping to protect, indigenous art covering miles of ground in southern Peru.

Gouged into a barren stretch of pampa in southern Peru, the Nazca Lines are one of archaeology’s most perplexing mysteries. On the floor of the coastal desert, the shallow markings look like simple furrows. But from the air, hundreds of feet up, they morph into trapezoids, spirals and zigzags in some locations, and stylized hummingbirds and spiders in others. There is even a cat with the tail of a fish. Thousands of lines jump cliffs and traverse ravines without changing course; the longest is bullet-straight and extends for more than 15 miles.

The vast incisions were brought to the world’s attention in the mid-1920s by a Peruvian scientist who spotted them while hiking through the Nazca foothills. Over the next decade, commercial pilots passing over the region revealed the enormousness of the artwork, which is believed to have been created from 200 B.C. to 700 A.D. by a civilization that predated the Inca.

The newly found images — an average of 30 feet across — could have been detected in past flyovers if the pilots had known where to look. But the pampa is so immense that “finding the needle in the haystack becomes practically impossible without the help of automation,” said Marcus Freitag, an IBM physicist who collaborated on the project.

To identify the new geoglyphs, which are smaller than earlier examples, the investigators used an application capable of discerning the outlines from aerial photographs, no matter how faint. “The A.I. was able to eliminate 98 percent of the imagery,” Dr. Freitag said. “Human experts now only need to confirm or reject plausible candidates.”

Source: The New York Times

Backup link: Archive Buttons

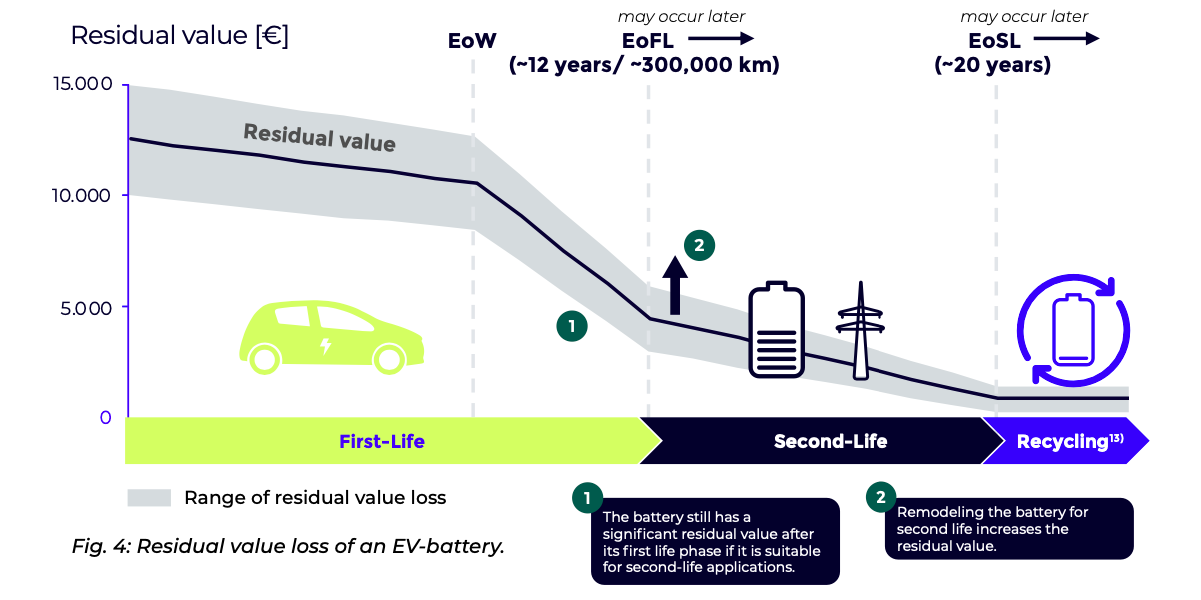

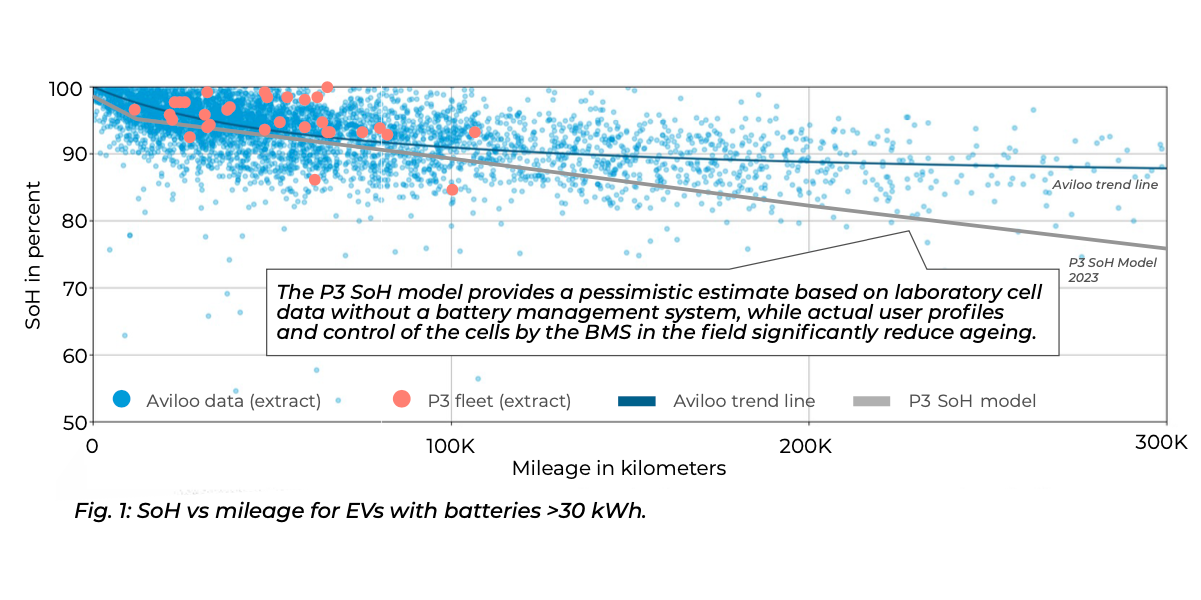

EV batteries live way longer than assumed

Last year, I leased an electric vehicle (EV) for the first time: a Polestar 2. It’s incredible; I wouldn’t even consider any other type of car in future.

I don’t have to worry about how long the physical batteries will last, but it’s something that EV skeptics, conspiracy theorists, and fossil fuel lobbyists tend to focus on. That’s why it’s good to see the management consultancy P3 conducting a study to counter some EV battery myths.

The term ‘state of health’ or SoH doesn’t have a standard definition, so it’s just used in this context to refer to EV battery capacity. The findings? Basically that EV batteries last way longer than was assumed. And, given that they can have a second and even third life after being removed from a car, there’s really no reason not to switch to an EV, pronto.

The field data suggests that the actual battery capacity is maintained longer than assumed under real-life conditions, especially with the often-cited high mileages of 200,000 kilometres and more. Based on the cell lab tests, the SoH model published by P3 in 2023 gave a much more pessimistic forecast for battery health. Up to around 50,000 kilometres, the laboratory model and the field data are roughly the same – above 100,000 kilometres. However, the trend lines diverge significantly. P3 concludes that the actual user-profiles and the control of the cells by the battery management system in the field significantly reduce ageing.

But how can the observed variation be explained? After all, some vehicles still have an extremely high SoH after more than 50,000 kilometres, while individual vehicles are still at 98 per cent after almost 200,000 kilometres – while others quickly fall below 90 per cent. In fact, the charging and usage behaviour of drivers and the vehicles themselves influence this, as do the manufacturers. On the one hand, the intended buffer (i.e., the difference between gross and net capacity) plays an important role in terms of size and utilisation of the buffer. That is because it can be used, for example, to reduce the noticeable ageing during the warranty period – by releasing a little more net capacity over time. On the other hand, the charging behaviour can be adjusted via a software update. On the one hand, this can be a higher charging power for shorter charging times, which leads to more stress in the cell. On the other hand, it is also possible that an update improves the control of the cells, for example, by optimising preconditioning to reduce stress during fast charging under sub-optimal conditions.

Source: electrive

From the 'everything fun is also bad' department

Data, or rather organised data is an incredibly valuable commodity in the modern world. Large Language Models (LLMs) which underpin the latest generative AI applications need ever-increasing amounts of it to develop more complex functionality.

Pokémon Go was controversial when it came out because there were so many people playing it that it was causing chaos when so-called ‘gyms’ and game characters were randomly placed in various real-world neighbourhoods. Now it transpires that the makers of the game are developing the equivalent of an LLM for ‘visual positioning’ and that this might be used for military applications. FML, as they say.

Uh, so here’s something interesting. Niantic, the company behind Pokémon Go, published a long blog post last week outlining a new project they’ve been working on called a Large Geospatial Model, essentially a Large Language Model but for visualizing and mapping physical space. They’re calling it the Visual Positioning System, or VPS, and they plan to use it for future augmented reality products and robotics. The idea of mapping the whole world has been a big priority for Niantic over the last few years.

One new feature for Pokémon Go that uses VPS is called Pokémon Playgrounds and it lets a user place a virtual Pokémon on a location and other players will find that Pokémon where they left it.

Though, as Elise Thomas, over at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, pointed out, it seems almost undeniable that this will not just power fun game mechanics. “It’s so incredibly 2020s coded that Pokemon Go is being used to build an AI system which will almost inevitably end up being used by automated weapons systems to kill people,” Thomas wrote.

Source: Garbage Day

Image: David Grandmougin

Tuvalu's Digital Twin

I initially thought this announcement from Tuvalu was from this month’s COP meeting, COP29. But it turns out that it was announced two years ago, and the update below was announced last year, at COP28.

It’s a sad but fascinating prospect: a nation without land, preserved digitally and with services available to the Tuvaluan diaspora after climate change means their physical territory disappears beneath the waves.

This is a more extreme version of Estonia’s e-Residency programme which was launched a decade ago. In that case, the threat was from other nation states, namely Russia.

I remember quite a few years ago at the Thinking Digital conference, just as the cryptocurrency craze was beginning, someone stood on stage and predicted the death of nation states, with people instead choosing digital nationhood. I don’t think it will be as binary as that. It’s much more likely to be something akin to dual nationality.

With time running out, Tuvalu has no choice but to start planning for this worst-case scenario. At COP27 (2022), Tuvaluan Minister Simon Kofe announced that Tuvalu will become the First Digital Nation: that it would digitally recreate its land, archive its rich history and culture, and move all governmental functions into a digital space.

This digital transformation will allow Tuvalu to retain its identity and continue to function as a state, even after its physical land is gone. It will also facilitate the governance of a Tuvaluan diaspora by creating a virtual space where Tuvaluans can connect with each other, explore ancestry and culture, and access new opportunities for business and commerce in various industries. Moreover, a permanent digital replica of Tuvalu – a new “defined territory” – will aid in the fight for continued sovereignty under international law.

Since the initial announcement of the First Digital Nation, Tuvalu has:

- Completed a comprehensive three-dimensional LIDAR scan of all 124 islands and islets, laying the foundation for its digital nation and helping redefine its territory in the eyes of international law.

- Begun upgrading its national communications infrastructure with the installation of two submarine cables, ensuring sufficient bandwidth for the transition to the cloud.

- Started exploring a digital ID system, which will use the blockchain to connect the Tuvaluan diaspora and allow them to participate in Tuvaluan life, wherever they are.

- Begun building a living archive of Tuvaluan culture, curated by its people. Citizens will be invited to contribute their most treasured personal items for digital preservation, creating a living record of Tuvaluan values.

- Amended its constitution to reflect a new definition of statehood – the first of its kind in the world. The amendment pronounces that the State of Tuvalu within its historical, cultural, and legal framework shall remain in perpetuity in the future, notwithstanding the impacts of climate change or other causes resulting in loss to the physical territory of Tuvalu.

Source: Tuvalu.tv

We don’t write things down to remember them. We write them down to forget.

My workflow for Thought Shrapnel is roughly: come across interesting article, save it to Pocket, revisit and write about it. There are plenty of articles that I don’t write about, and I sometimes go on hiatus from this blog for a while.

As I get older, I don’t really understand the desire to capture all of the things and link them together. It can become fetishistic, and obession. I seem to do alright in my personal and professional lives in terms of remembering stuff and combining them in new and interesting ways. And don’t particularly have a ‘system’. I just remember stuff that I’ve written about, and especially when I’ve written about it multiple times.

This article talks about the freedom of forgetting stuff. We’re loathe to let things go into the ether because we ascribe value to the things we’ve collected. However, I suppose because I’ve collected, written, and jettisoned so much stuff in my life, I’m very comfortable in getting rid of it. I don’t need a million tabs open, a bookmarks manager stuffed with links, or a meticulous system. My approach is based on curiosity, interest, and writing about stuff.

That’s the true value of notebooks, notes apps, bookmarking tools, and everything else built to help us remember. They’re insurance for ideas. They let us forget.

[…]

We need to forget, but we first must feel safe forgetting.

[…]

We didn’t need bookmarks and notes as much as we needed the safety of letting go. Anywhere we could save our thoughts was enough.

Source: Reproof

Image: Omar Al-Ghosson

Scrolling on your phone is not a hobby

I came across this blog post this morning and I can’t stop thinking about it. I wish I’d seen it when it was published a few months ago.

The author gives it the provocative title The Mainstreaming of Loserdom, explaining that it seems to have become normal for people to not only admit to having “no hobbies, no interests, no verve,” but be positively “gleeful” about it. It seems that a trend that had already been set in motion was accelerated due to the pandemic.

I needed to share the post here because I’m conflicted about it. On the one hand, I’ve never had a particularly interesting social life — at least by other people’s standards. On the other, I’m one of the people the author talks about that creates stuff on the internet.

What I think we’ve got is more people online than ever before, and so a larger sub-section of people who are, if not clinically depressed, certainly acting in a way that gives off morose vibes. They’re living life through the lens of consumption, something which our economic system incentivises. After all, it’s difficult to monetise people just hanging out having a chat. Unless it’s a podcast, I guess 😉

It was clear twenty years ago that someone who rarely engaged with their peers, didn’t really have friends, and didn’t really leave their house wasn’t aspirational: they were odd.

I know what people are going to say: not everyone drinks, not everyone parties, we have social anxiety, everything is too expensive… People simply aren’t connecting the way they used to, and I won’t be the bad guy for pointing out that it doesn’t surprise me that people are desperately lonely while also saying their favorite hobby is… staying home.

[…]

I’ll also defend myself preemptively and say not everyone has the same threshold for social interaction, which again, is fine. My issue is that I do not believe that the millions of people engaging with these posts all have very literal tolerance for social interaction.

[…]

I’ve been on the internet for twenty years: I’ve been on fanfiction.net, I’ve been on Livejournal, I’ve been on Tumblr. I was surrounded by people who spent time alone, but they were creating. They were writing, they were generating, they were knitting and sewing and painting and dreaming. The specific activity I’m talking about is a lack of any of this. The people screaming from their rooftops about how they don’t go anywhere and don’t have any friends aren’t the same people writing 70,000 words of Harry/Draco smut, I’m sorry! I know my people, and this feels different. It feels more sinister. Posting fanfiction online is a bid for community. Scrolling on your phone is not.

Source: Telling the Bees

Transmission interrupted: signal lost

Forms of perceptual learning

“The systems approach begins when first you see the world through the eyes of another” wrote C. West Churchman. Seeing things from another’s point of view is usually framed as ‘empathy’ but often what isn’t discussed is the effect that a change in perspective can have on a person themselves. This is sometimes colloquially and humorously referred to as “things we cannot unsee”. It’s automatic: the way we understand the world has changed.

Stephen Downes shared this recently-updated article from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy about a topic which I’ve only studied obliquiely. ‘Perceptual learning’ is about long-lasting changes in perception resulting from practice or experience, and can take four forms: differentiation, unitization, attentional weighting, and stimulus imprinting.

When most people reflect on perceptual learning, the cases that tend to come to mind are cases of differentiation. In differentiation, a person comes to perceive the difference between two properties, where they could not perceive this difference before. It is helpful to think of William James’ case of a person learning to distinguish between the upper and lower half of a particular kind of wine. Prior to learning, one cannot perceive the difference between the upper and lower half. However, through practice one becomes able to distinguish between the upper and lower half. This is a paradigm case of differentiation.

[…]

Unitization is the counterpart to differentiation. In unitization, a person comes to perceive as a single property, what they previously perceived as two or more distinct properties. One example of unitization is the perception of written words. When we perceive a written word in English, we do not simply perceive two or more distinct letters. Rather, we perceive those letters as a single word. Put another way, we perceive written words as a single unit (see Smith & Haviland 1972). This is not the case with non-words. When we perceive short strings of letters that are not words, we do not perceive them as a single unit.

[…]

In attentional weighting, through practice or experience people come to systematically attend toward certain objects and properties and away from other objects and properties. Paradigm cases of attentional weighting have been shown in sports studies, where it has been found, for instance, that expert fencers attend more to their opponents’ upper trunk area, while non-experts attend more to their opponents’ upper leg area (Hagemann et al., 2010). Practice or experience modulates attention as fencers learn, shifting it towards certain areas and away from other areas.

[…]

Recall that in unitization, what previously looked like two or more objects, properties, or events later looks like a single object, property, or event. Cases of “stimulus imprinting” are like cases of unitization in the end state (you detect a whole pattern), but there is no need for the prior state—no need for that pattern to have previously looked like two or more objects, properties, or events. This is because in stimulus imprinting, the perceptual system builds specialized detectors for whole stimuli or parts of stimuli to which a subject has been repeatedly exposed (Goldstone 1998: 591). Cells in the inferior temporal cortex, for instance, can have a heightened response to particular familiar faces (Perrett et al., 1984, cited in Goldstone 1998: 594).

Source: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Image: CHUTTERSNAP

Llama 3 is only free to use until monthly active users exceed 700m

Amidst the drama around the WordPress project at the moment (which is, in my experience only a public version of what goes on behind the scenes of any major Open Source project) I was interested in a post by Matt Mullenweg.

I’ve been using Llama 3 on projects where it wouldn’t be appropriate to use OpenAI’s offerings, but I should have known that, given it’s from Meta, there would be some shenanigans. And so it proves.

I’ll not share the rest of the post, given Matt’s ‘ecosystem thinking’ seems a bit disingenuous given the spat he’s engaged in, but this bit shocked me.

Open Source, once ridiculed and attacked by the professional classes, has taken over as an intellectual and moral movement. Its followers are legion within every major tech company. Yet, even now, false prophets like Meta are trying to co-opt it. Llama, its “open source” AI model, is free to use—at least until “monthly active users of the products or services made available by or for Licensee, or Licensee’s affiliates, is greater than 700 million monthly active users in the preceding calendar month.” Seriously.

Excuse me? Is that registered users? Visitors to WordPress-powered sites? (Which number in the billions.) That’s like if the US Government said you had freedom of speech until you made over 50 grand in the preceding calendar year, at which point your First Amendment rights were revoked. No! That’s not Open Source. That’s not freedom.

I believe Meta should have the right to set their terms—they’re smart business, and an amazing deal for users of Llama—but don’t pretend Llama is Open Source when it doesn’t actually increase humanity’s freedom. It’s a proprietary license, issued at Meta’s discretion and whim. If you use it, you’re effectively a vassal state of Meta.

When corporations disingenuously claim to be “open source” for marketing purposes, it’s a clear sign that Open Source is winning.

Source: Ma.tt

Image: Managing Data Hazards by Yasmin Dwiputri & Data Hazards Project

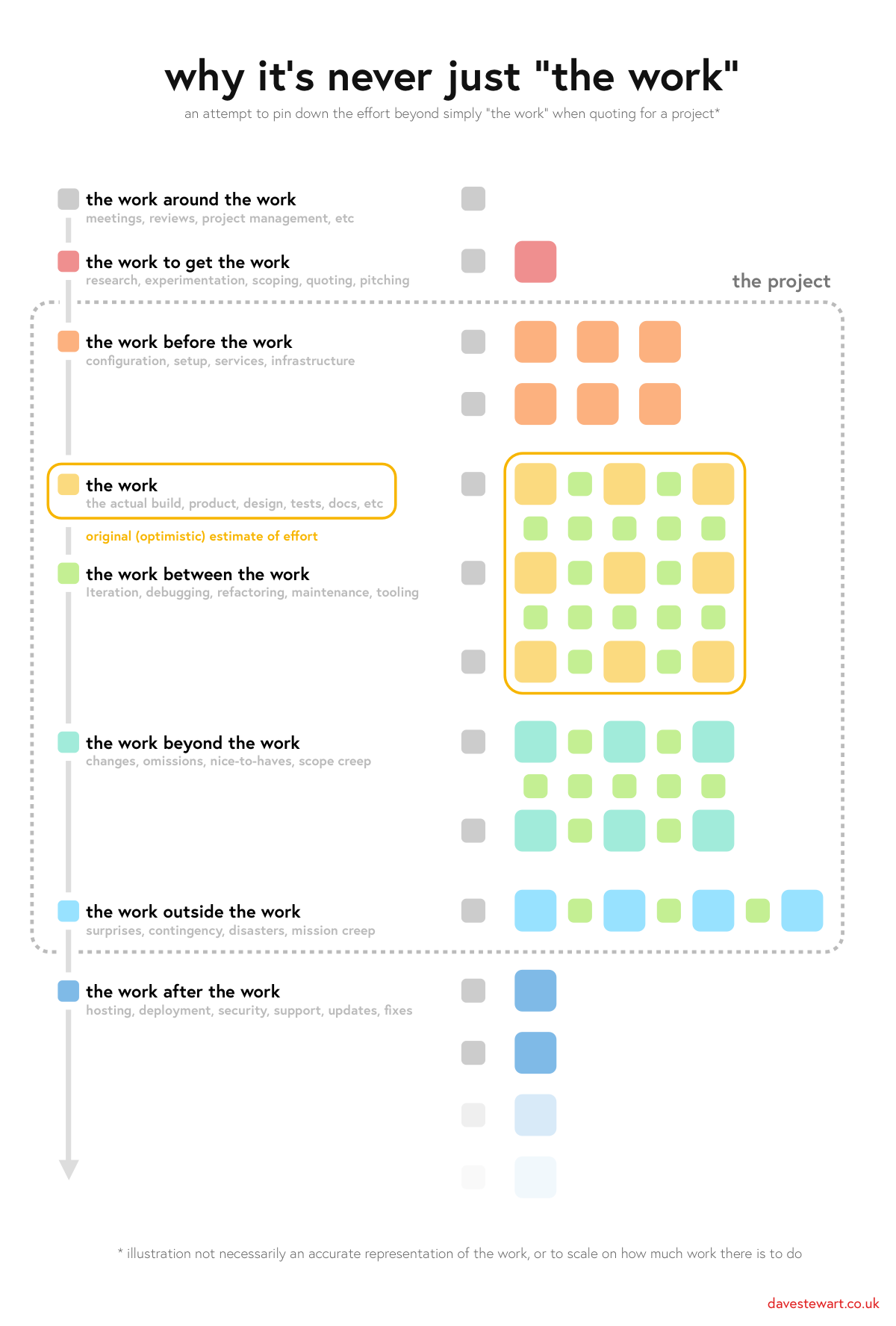

The work to do the work

Abi Handley shared the above image on LinkedIn from a web developer who, back in 2022, worked out all of the time they spent on a project. Unsurprisingly, as anyone who has ever led a project will know, it’s the “work to do the work” which takes the most time.

When you’re younger, enthusiasm, energy and naivety tend to get you to the end of a project. When you’re in your forties, like me, it’s process. This post talks about running a ‘postmortem’ but we insist on pre-mortems as well as retrospectives. We minimise ‘status update’ meetings, using tools such as Trello to track task completion and Loom to explain things that would take too long via email.

Additionally, some people seem to think that being ‘professional’ means not bringing your emotions to work. But emotion is what makes us human, and so acknowledging this and factoring it into to projects is one of the keys to running them successfully.

I had been aware during the project that there seemed to be a lot of “extra work”, but putting it down on paper highlighted the multitude of “invisible” tasks and challenges which every web development project has.

There were two common threads:

- much of the work was the “work to do the work” rather than the “actual” work

- most of the work was under- or un-estimated because it wasn’t the “actual” work

Source: Dave Stewart

About time to head south for winter

I don’t think this is a new ‘False Knees’ cartoon, but it’s a great one and gave me a chuckle, especially at this time of the year. My SAD light is out, and it’s chilly in Northumberland.

Source: False Knees

Ocean acidification approaches the boundary

I feel like this should perhaps be bigger news?

Boundaries that have already been exceeded have to do with climate change, freshwater availability, biodiversity, land use, nutrient pollution (such as phosphorus and nitrogen) and the introduction of synthetic chemicals and plastics to the environment.

Ocean acidification is one of the systems that has not yet crossed its planetary boundary, along with ozone depletion and aerosols in the atmosphere. But while ocean acidification is still in the “green zone,” the new report finds it’s trending in the wrong direction. Scientists now say this metric is on the brink and may cross out of the safe zone in the next few years.

Earth’s oceans absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, providing a valuable carbon sink as humans burn fossil fuels. But this process also makes the oceans more acidic, which can disturb the formation of shells and coral skeletons and affect fish life cycles, per the report.

As ocean acidification approaches the boundary, scientists are particularly concerned about certain regions, like the Arctic and Southern oceans. These areas are vital for carbon and global nutrient cycles, “which support marine productivity, biodiversity and global fisheries,” the report says.

Source: Smithsonian Magazine

A Troll's Charter

Given the groups who financed Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to see the events relating to the platform over the past few years as an attempt to stifle progressive discourse.

It’s been seven years since I deleted 77.5k tweets I composed between 2007 and 2017. I could see the way the wind was blowing, even before Musk’s acquisition. The latest news is that blocked users will still be able to see the tweets of the person who’s blocked them, which is just a troll’s charter.

If, for some reason, you’re still on there, perhaps it’s time to leave?

X will now make your posts visible to users you’ve blocked. In a reply on Monday, X owner Elon Musk said the “block function will block that account from engaging with, but not block seeing, public post.”

[…]

Musk has been vocal about his dislike of the block button. Last year, he said the feature “makes no sense” and that “it needs to be deprecated in favor of a stronger form of mute.” He also threatened to stop letting users block people on the platform completely, except for direct messages.

Source: The Verge

Image: BoliviaInteligente

A countercultural perspective to the capitalist notion of 'productivity'

This article examines how religious communities, particularly nuns and monks, approach productivity differently from the modern, output-driven culture. It highlights how members of religious orders redefine productivity as rooted in spiritual fulfilment, sufficiency, and human connection rather than constant work and economic gain.

These experiences suggest that true productivity lies in fruitfulness and grace, not in relentless efficiency, which offers somewhat of a countercultural perspective to the capitalist emphasis on always doing more.

We are conditioned to listen to podcasts while washing up, read books on the commute and dash out emails while drinking a morning coffee. I can’t even ‘just’ watch a Netflix show without needing something else to do, so resort to doing cross stitch in front of the TV in order to put my phone down. This is the efficiency for which we congratulate ourselves, getting more done in the same time. I draw the line at the growing trend for listening to podcasts at double speed to inhale the same information more efficiently, less fruitfully.

When I first raised the idea of writing this piece, and put out the rather niche call for nuns, priests and monks willing to be interviewed about productivity culture, I was struck by the number of responses from people desperate to read it. The desire for wisdom about life and work that isn’t geared just towards increasing the latter is real.

There were points in every one of the conversations I had with Sister Liz, Sister Gabriel, Father Thomas and Father Sam, in the middle of my working day, that felt like a mirror being held up, both gently and painfully, to the busyness and imbalance of my own life. If Melville was right that nothing is what it is except for contrast, then the lessons of the religious life for those of us grappling with the need to be ‘productive’ are surely our greatest example.

Source: THEOS

A landscape of havoc and fracture

The last paragraph of this post by Julian Stodd, which I discovered via OLDaily, points to something emancipatory about generative AI that I think some people may have missed:

An interesting feature of the Generative AI revolution is that whilst the technologies themselves are monumental, both in terms of complexity and physical energy and scale, it may well be individuals, at scale, who drive the true change. Not a single technology that breaks in, but rather people breaking out. Breaking out of restrictive and constrained structure.

Stodd is part of a doctoral programme, and (with no lack of hyperbole) discusses how his cohort is likely to be “the last to really read books… to really write for myself… to be confused and lost in thought.” He calls this a “landscape of havoc and fracture” and points to four dimensions of this shift:

Dialogic Engines – synchronous iteration and exploration of ideas, warping legacy ideas of trust, self doubt, foolishness, failure, and curiosity. As we wrote in ‘Engines of Enagement’, Generative AI makes high quality dialogue a commodity, but not simply as a service – it shifts the social context of such. So we can be in dialogue as a solo feature, removing all social judgement of curiosity and ignorance, if we dare.

Agentic Retrieval – not just a search engine, but a context setting system. These tools can shift the boundaries of context – not telling us what we asked for, but giving us what we may need. And from a perspective of virtually unbounded knowledge. We can factor this into our dialogue – asking for breadth and challenge to our thinking – or we may find it just lands. I think that systems shifting context is highly significant, as the fracture and evolution of context is a key part of insight and even paradigmatic change.

Trans-disciplinarity as the norm: our taxonomies of knowledge are not natural, but rather shaped by legacy mechanisms of need, discovery, ownership, and understanding. We have tended to segment our knowledge and hence structures of learning (as well as power, status, and identity) vertically around these themes. So we have engineers and poets, but not many poetic engineers. I think Generative AI changes this in significant ways, if we allow it to: permits a broadening of vocabulary and conception, a translation engine if you like, but also a provocative one – if we ask or if it offers.

The Primacy of Sense Making: I’ve said for some time that knowledge itself is shifting in the context of the Social Age, and Generative AI scales this change. The latest GenAI tools are Engines of Synthesis, reflection and contextualisation, leaving us in a radically broadened landscape of sense making as individual and collective feature. And I don’t think sense making per se is at threat of absorption by technology. Not that the Engines cannot make sense, just that our act of consumption is inherently linked to re-contextualisation and insight. In other words, if the technology has already chewed it over, we will chew it over again. It just broadens the space and foundations for us to do so.

I’ve been using GPT-4o for my MSc and it’s so much better and deeper to learn with an assistant than to rely on what’s provided to you as a student, and what you can discover by just wading through books and articles.

Source: Julian Stodd’s Learning Blog

Leadership, gender, and 'abusive supervision'

Prof. Ivona Hideg writes about a study she carried out during the pandemic around men and women leaders. While both experienced higher levels of anxiety, the amount of ‘abusive supervision’ was lower in women. The study was limited in terms of gender identification and sexual orientation, but it’s still interesting.

For me, this study supports what I have experienced in my career to date: women tend to be better at regulating their emotions, which the exact opposite of the stereotype of women in leadership positions.

In our research, we investigated 137 leader-report pairs working in Europe (primarily the Netherlands) in the service (38%), public (28%), or information and technology (23%) sectors during the early phases of the pandemic in 2020. The majority of leaders were men (56%), Dutch (59%), white (92%), and heterosexual (95%). The majority of direct reports were women (56%), Dutch (60%), white (89%), and heterosexual (88%). These leaders reported their emotions during the pandemic; their reports then rated their leaders’ behaviors.

Women leaders reported higher levels of anxiety regarding the pandemic than men leaders. There were no gender differences in feelings of hope toward the pandemic. When leaders’ anxiety was higher, so was their abusive supervision, whereas when leaders’ hope was higher, so was their family-supportive supervision. Critically, supporting our hypotheses, we found that these relationships between leaders’ emotions and behaviors depended on their gender. Leaders’ emotions were only related to their leadership behaviors if they were men, but not if they were women.

Namely, in line with gender role and emotional labor theory, women leaders engaged in low levels of abusive supervision regardless of how anxious they felt about the pandemic. By contrast, men leaders engaged in more abusive supervision, including behaviors such as being rude, ridiculing, yelling at, or lying to their reports when their anxiety was higher. Women leaders also provided high levels of family-supportive supervision irrespective of how hopeful they felt about the pandemic. By contrast, men leaders provided family-supportive supervision only when they felt more hopeful.

Source: Harvard Business Review

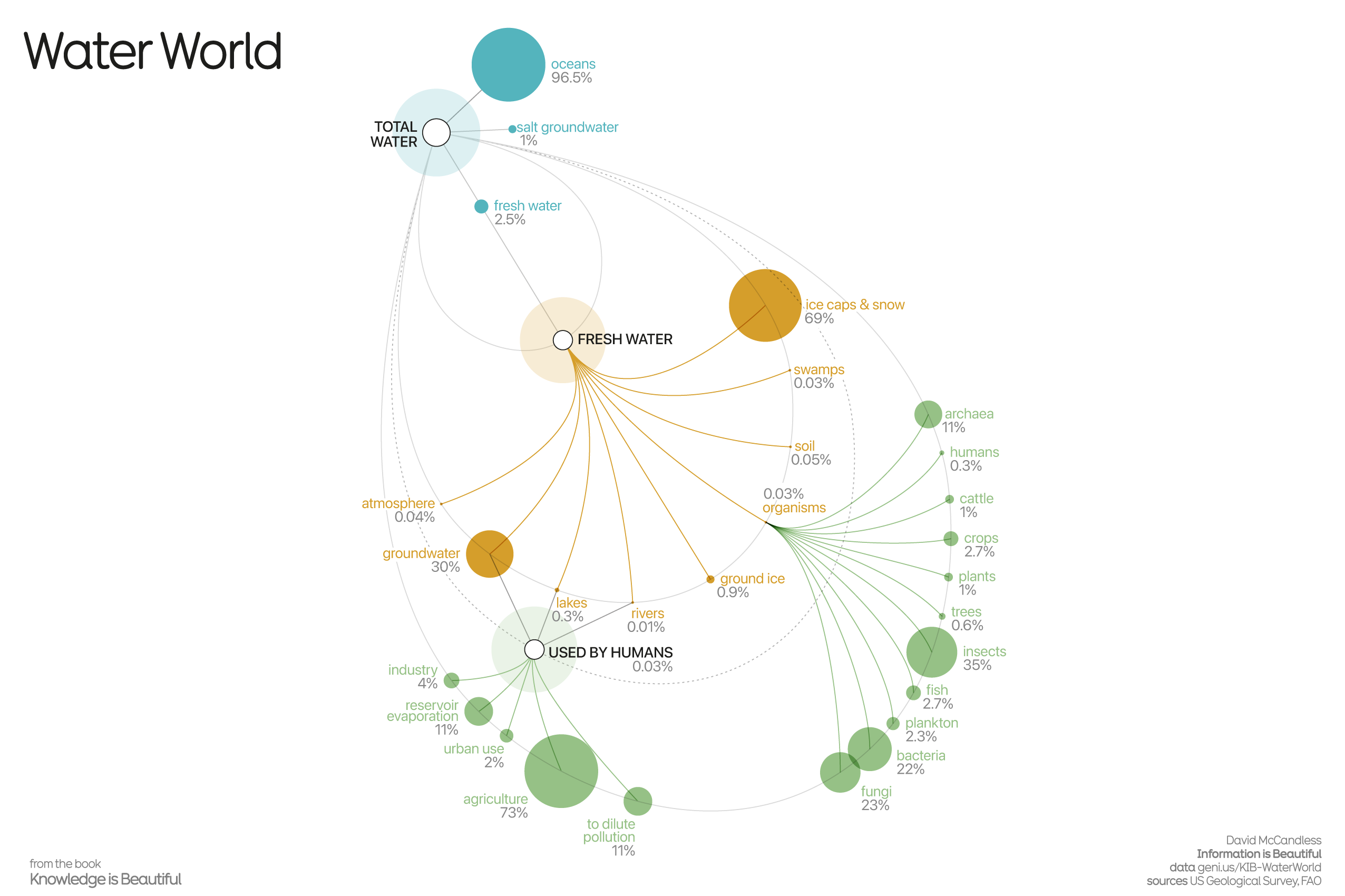

Water use literacy

We’ve just started on a Mozilla-funded Friends of the Earth project at the moment around sustainability principles for AI. There seems to be a lot of noise around the amount of water employed to cool the data centres used to train large language models (LLMs).

While we should always be cognisant of the amount of the energy and water used to provide us with new (and existing) technologies, I think there’s a lack of statistical numeracy going on here. For example, in the UK, 51 litres of water per person are lost due to leakage every day. That’s over a trillion litres per year!

Alan Levine shared a link to this visualisation in the thread where I was discussing this stuff on the Fediverse.

Source: Information is Beautiful

Against cyberlibertarianism

A long-ish and important post by Paris Marx in which he argues for a middle path between the ‘cyberlibertarianism’ of Silicon Valley and the China firewall approach. Just as the laws in most countries have a common based but a different flavour, so I think we’ll see an increasing alignment of what’s allowed online with what’s allowed offline in various jurisdictions.

Instead of solely fighting for digital rights, it’s time to expand that focus to digital sovereignty that considers not just privacy and speech, but the political economy of the internet and the rights of people in different countries to carve out their own visions for their digital futures that don’t align with a cyberlibertarian approach. When we look at the internet today, the primary threat we face comes from massive corporations and the billionaires that control them, and they can only be effectively challenged by wielding the power of government to push back on them. Ultimately, rights are about power, and ceding the power of the state to right-wing, anti-democratic forces is a recipe for disaster, not for the achievement of a libertarian digital utopia. We need to be on guard for when governments overstep, but the kneejerk opposition to internet regulation and disingenuous criticism that comes from some digital rights groups do us no good.

The actions of France and Brazil do have implications for speech, particularly in the case of Twitter/X, but sometimes those restrictions are justified — whether it’s placing stricter rules on what content is allowable on social media platforms, limiting when platforms can knowingly ignore criminal activity, and even banning platforms outright for breaching a country’s local rules. We’re entering a period where internet restrictions can’t just be easily dismissed as abusive actions taken by authoritarian governments, but one where they’re implemented by democratic states with the support of voting publics that are fed up with the reality of what the internet has become. They have no time for cyberlibertarian fantasies.

Counter to the suggestions that come out of the United States, the Chinese model is not the only alternative to Silicon Valley’s continued dominance. There is an opportunity to chart a course that rejects both, along with the pressures for surveillance, profit, and control that drive their growth and expansion. Those geopolitical rivals are a threat to any alternative vision that rejects the existing neo-colonial model of digital technology in favor of one that gives countries authority over the digital domain and the ability for their citizens to consider what tech innovation for the public good could look like. Digital sovereignty will look quite different from the digital world we’ve come to expect, but if the internet has any hope for a future, it’s a path we must fight to be allowed to take.

Source: Disconnect

Image: Tjeerd Royaards