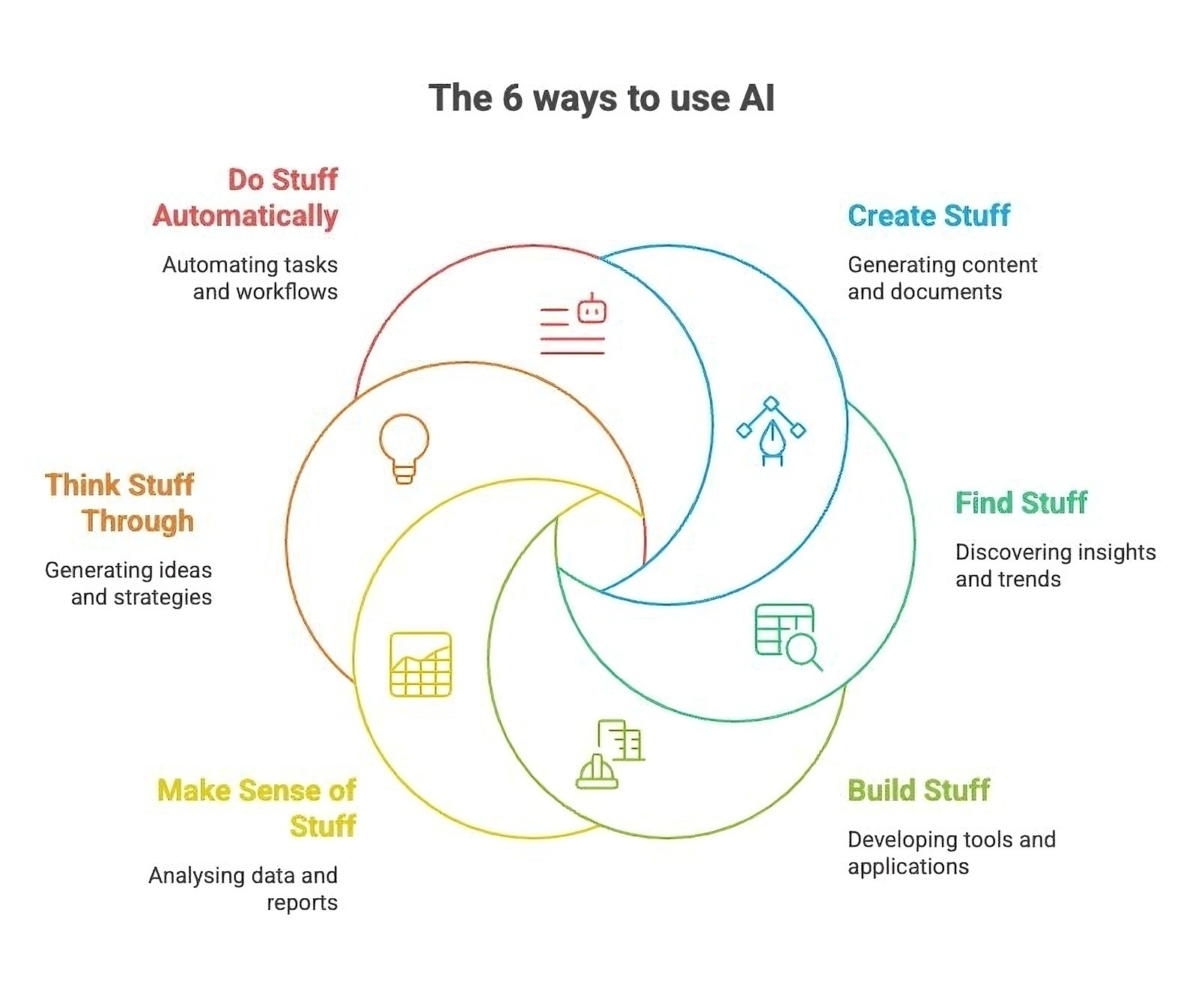

6 AI use case primitives

It’s not often I link directly to a LinkedIn post. However, the author of this, Ben Cohen, doesn’t seem to have posted it elsewhere, so needs must. Cohen also doesn’t cite the original source of the analysis he references, but it looks like it comes from an OpenAI report entitled Identifying and scaling AI use cases in which the “six use case primitives” are:

- Content creation

- Research

- Coding

- Data analysis

- Ideation/strategy

- Automation

Cohen has renamed these into much snappier “stuff” language, along with a graphic (see above) which looks like the OpenAI logo. I like this framing, it resonates.

I do wonder how many of these six use cases that vehemently anti-AI critics have actually used. I can confidently say I’ve used them all, and probably hit four of the six categories most working days at the moment.

Turns out there are only six ways to use AI well.

OpenAI looked at 600+ of the most successful GenAI use cases.

Every single one fell into just 6 categories (which I’ve taken the liberty to rename):

Create stuff → Content, policies, presentations, images, emails, contracts

Find stuff → Insights, research, competitor analysis, trends

Build stuff → Tools, websites, apps

Make sense of stuff → Data analysis, dashboards, performance reports

Think stuff through → Idea generation, strategies, decision-making

Do stuff automatically → Workflows, email automation, customer chatbots

That’s it.

Source & image: Ben Cohen | LinkedIn

The workload fairy tale

Most people are very surprised when I say that I work around 20-25 hours per week. I then clarify that this is paid work, so not things like blogging, doing lots of reading, looking for business development leads, giving free advice, etc.

Still, it means that I have a life where I can exercise every day, be around for my kids, and manage my stress/anxiety levels. While not everyone runs their own business, most knowledge workers do have a fair amount of freedom. As Cal Newport points out in this article, the 4-day workweek is a way of pushing back against the expectation that a company owns all of your time.

So, I’d say that the 4-day workweek is more of a mindset change, especially if you’re getting done the same amount as before. I’d definitely try it! When I worked at Moodle, I did a 4-day week, and being able to say “I won’t be able to as I don’t work Fridays” or similar is as much as a story you tell yourself as one you tell other people.

Another thing, which we try and do at WAO is to co-work on projects, and not to switch between multiple projects within one day. So, if we’ve got three projects on the go, we’ll try and dedicate either a whole day to one, or a morning to one, an afternoon to another, and leave the third until the next day. Of course, it doesn’t always work out like that, but collaborating with others (not just having meetings with them!) and allocating time to different projects makes them not only manageable, but… maybe even enjoyable?

Most knowledge workers are granted substantial autonomy to control their workload. It’s technically up to them when to say “yes” and when to say “no” to requests, and there’s no direct supervision of their current load of tasks and projects, nor is there any guidance about what this load should ideally be.

Many workers deal with the complexity of this reality by telling themselves what I sometimes call the workload fairy tale, which is the idea that their current commitments and obligations represent the exact amount of work they need to be doing to succeed in their position.

The results of the 4-day work week experiment, however, undermine this belief. The key work – the efforts that really matter – turned out to require less than forty hours a week of effort, so even with a reduced schedule, the participants could still fit it all in. Contrary to the workload fairytale, much of our weekly work might be, from a strict value production perspective, optional.

So why is everyone always so busy? Because in modern knowledge work we associate activity with usefulness (a concept I call “pseudo-productivity” in my book), so we keep saying “yes,” or inventing frenetic digital chores, until we’ve filled in every last minute of our workweek with action. We don’t realize we’re doing this, but instead grasp onto the workload fairy tale’s insistence that our full schedule represents exactly what we need to be doing, and any less would be an abdication of our professional duties.

The results from the 4-day work week not only push back against this fairy tale, but also provide us with a hint about how we could make work better. If we treated workload management seriously, and were transparent about how much each person is doing, and what load is optimal for their position; if we were willing to experiment with different possible configurations of these loads, and strategies for keeping them sustainable, we might move closer to a productive knowledge sector (in a traditional economic sense) free of the exhausting busy freneticism that describes our current moment. A world of work with breathing room and margin, where key stuff gets the attention it deserves, but not every day is reduced to a jittery jumble.

Source: Cal Newport

Image: Dorota Dylka

The question remains, though, what will be left to browse.

Let’s say that, as often happens, I half-remember an article that I’ve been reading. It’s not in my Reader saves, so what am I going to do? Even this time last year, I would have typed what I could remember into my browser address bar, which would then take me to my default search engine: DuckDuckGo.

Over the last few months, however, for anything more complex than just quickly looking something up, I’ve been using Perplexity, which allows you to search the web (default), as well as academic and social sites such as Reddit. Unlike other LLMs, its not sycophantic, and it always shows its sources.

Casey Newton discusses the advent of the AI-first browser which uses ‘agents’ to go searching on your behalf. I’m kind of already doing this. And before you judge me, let’s just reflect on the fact that almost 40% of people click on the first result on Google results, and [fewer than 0.5% go past the first page of search engine results. So even an LLM that goes out, reads 20 links and presents back the most salient results is already doing a better job.

[T]he decline of the web has been met with a surprising counter-phenomenon: a huge investment in new web browsers.

On Wednesday, Opera — the Norwegian company whose namesake browser commands about 2 percent market share worldwide — announced that it is building a new browser.

Two days earlier, the Browser Company said it plans to open source its Arc browser and turn its efforts fully to a new one.

The moves came a few months after “answer engine” company Perplexity teased a new browser of its own called Comet. And while the company has not confirmed it, OpenAI has reportedly been working on a browser for more than six months.

It has been a long time since the internet saw a proper browser war. The first, in the earliest days of the web, saw Microsoft’s Internet Explorer defeat Netscape Navigator decisively. (Though not before a bruising antitrust trial.) In the second, which ran from roughly 2004 to 2017, new browsers from Mozilla (Firefox) and Google (Chrome) emerged to challenge Internet Explorer and eventually kill it. Today the majority of web users use Chrome.

[…]

“Traditional browsers were built to load webpages,” said Josh Miller, the Browser Company’s CEO, in a post announcing its forthcoming Dia browser. “But increasingly, webpages — apps, articles, and files — will become tool calls with AI chat interfaces. In many ways, chat interfaces are already acting like browsers: they search, read, generate, respond. They interact with APIs, LLMs, databases. And people are spending hours a day in them. If you’re skeptical, call a cousin in high school or college — natural language interfaces, which abstract away the tedium of old computing paradigms, are here to stay.”

Perplexity is one of my pinned tabs both on my desktop and laptop. I use it multiple times every day in both professional and personal contexts, for example when researching information that is helping me make a decision about car leasing. This year, I’ve also used it to help decipher medical records, pull out information from extremely dense reports, and synthesise information from multiple sources.

It does feel a bit like a superpower when you use these things well. But, as Newton points out, as the business model for putting content on the web fails, where are AI browsers going to get their information from?

[I]t’s easy to imagine the possibilities for an AI browser. It could function as a research assistant, exploring topics on your behalf and keeping tabs on new developments automatically. It could take your to-do list and attempt to complete tasks for you while you’re away. It could serve as a companion for you while you browse, identifying factual errors and suggesting further reading.

[…]

The question remains, though, what will be left to browse. The entire structure of the web — from journalism to e-commerce and beyond — is built on the idea that webpages are being viewed by people. When it’s mostly code that is doing the looking, a lot of basic assumptions are going to get broken.

Source: Platformer

Image: almoya

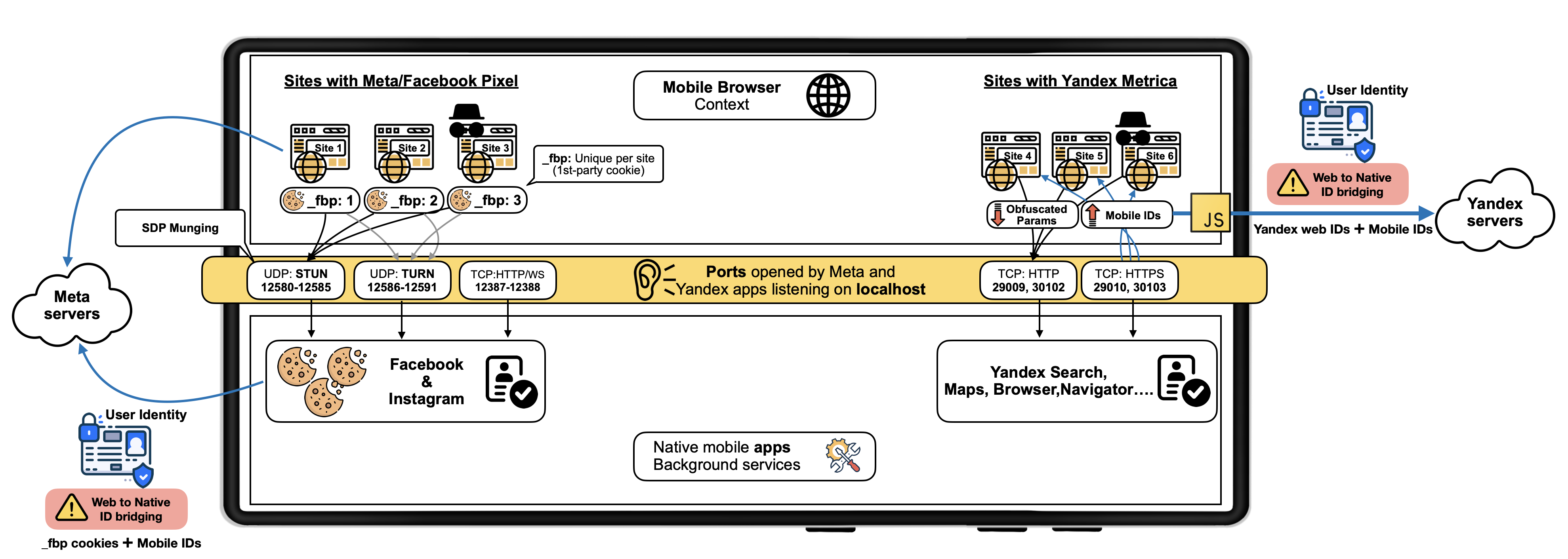

Maximum fines have never before been applied simultaneously, but some might say these scoundrels have earned it.

Technical things don’t interest most people. I’m definitely at the edges of my understanding with this one, but the implications are pretty huge. Essentially, Meta (the organisation behind Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) and Yandex have been caught covertly tracking users on Android devices via a novel method.

On the day that this disclosure was made public, Meta “mysteriously” stopped using this technique. But, by that point, they’d been using it for well over six months, and it appears that Yandex (a Russian tech company) has been using it for EIGHT YEARS.

The website dedicated to the disclosure is, as you’d expect, pretty technical. But it does say this:

This novel tracking method exploits unrestricted access to localhost sockets on the Android platforms, including most Android browsers. As we show, these trackers perform this practice without user awareness, as current privacy controls (e.g., sandboxing approaches, mobile platform and browser permissions, web consent models, incognito modes, resetting mobile advertising IDs, or clearing cookies) are insufficient to control and mitigate it.

We note that localhost communications may be used for legitimate purposes such as web development. However, the research community has raised concerns about localhost sockets becoming a potential vector for data leakage and persistent tracking. To the best of our knowledge, however, no evidence of real-world abuse for persistent user tracking across platforms has been reported until our disclosure.

A Spanish site called Zero Party Data, which also posts in English explains what’s going in an easier-to-understand way:

Meta devised an ingenious system (“localhost tracking”) that bypassed Android’s sandbox protections to identify you while browsing on your mobile phone — even if you used a VPN, the browser’s incognito mode, and refused or deleted cookies in every session.

[…]

Meta faces simultaneous liability under the following regulations, listed from least to most severe: GDPR, DSA, and DMA (I’m not even including the ePrivacy Directive because it’s laughable).

GDPR, DMA, and DSA protect different legal interests, so the penalties under each can be imposed cumulatively.

The combined theoretical maximum risk amounts to approximately €32 billion** (4% + 6% + 10% of Meta’s global annual revenue, which surpassed €164 billion in 2024).

Maximum fines have never before been applied simultaneously, but some might say these scoundrels have earned it.

Briefly, here’s how it works (according to the above website):

- Step 1: The app installs a hidden “intercom”

- Step 2: You think, “hmm, nice day to check out my guilty pleasure website in incognito mode.”

- Step 3: The web pixel talks to the Facebook/Instagram app using WebRTC

- Step 4: The same pixel on your favorite website, without hesitation, sends your alphanumeric sausage over the internet to Meta’s servers

- Step 5: The app receives the message and links it to your real identity

This is why I don’t use apps from Meta and use a security-hardened version of Android called GrapheneOS

Sources: Local Mess / Zero Party Data

Image: Local Mess

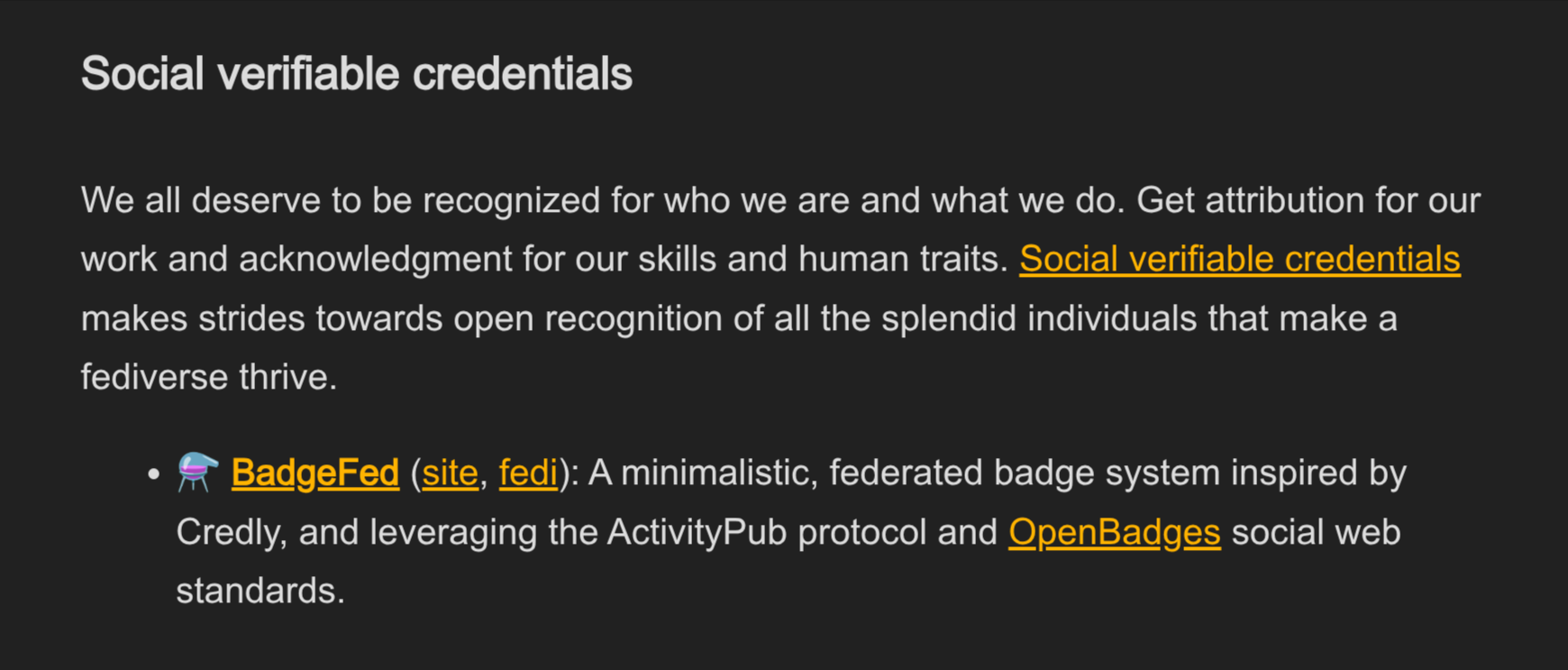

Delightful Fediverse apps

I’m sharing this list of “delightful fediverse apps” as it includes a couple of things (Bonfire, BadgeFed) in which I’m particularly interested. It’s also a great example of how many types of difference service can be created via a protocols-based approach.

A curated list of fediverse software that offer decentralized social networking services based on the W3C ActivityPub family of related protocols.

Source: delightful.coding.social

Expert-in-the-loop vs. layperson-in-the-loop

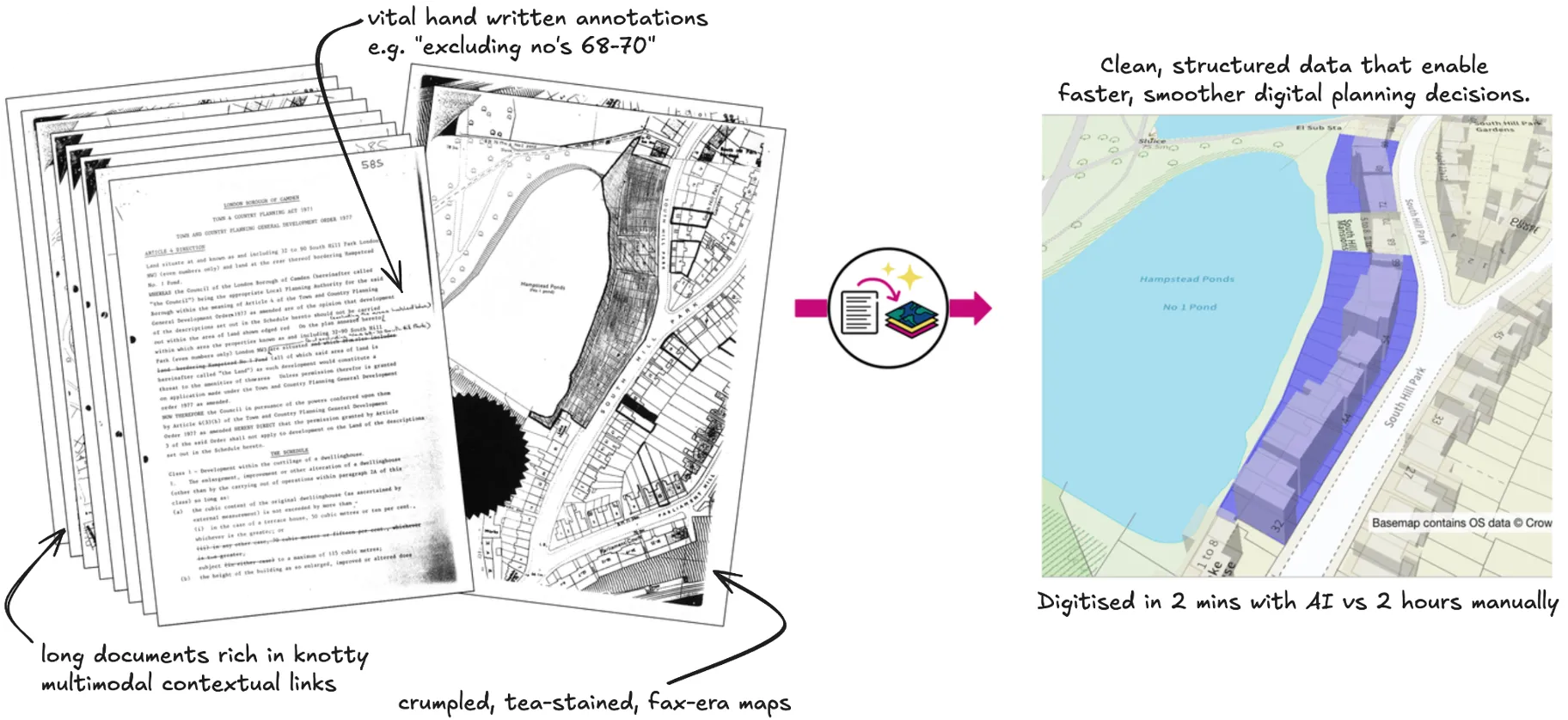

This is on a Google blog, so it foregrounds the use of their Gemini AI model in a new tool called Extract, built by the UK Government’s AI Incubator team. I should imagine that they’d be able to switch Gemini out for any model that has “advanced visual reasoning and multi-modal capabilities.” At least, I’d hope so.

So long as there is some kind of expert-in-the-loop, I think this is a great use of AI in public services. Planning in the UK, as I should imagine it is in most countries, is outdated, awkward, and slow. Speeding things up, especially if it allows multiple factors to be considered automatically, is a great idea.

A couple of years ago, I pored over technical documents I didn’t understand, feeding them into LLMs to try and figure out whether or not to buy a house by a river that had previously flooded, but now had flood defences. I was not an “expert-in-the-loop” but instead a “layperson-in-the-loop.” There’s a difference.

Traditional planning applications often require complex, paper-based documents. Comparing applications with local planning restrictions and approvals is a time-consuming task. Extract helps councils to quickly convert their mountains of planning documents into digital structured data, drastically reducing the barriers to adopting modern digital planning systems, and the need to manually check around 350,000 planning applications in England every year.

Once councils start using Extract, they will be able to provide more efficient planning services with simpler processes and democratised information, reducing council workload and speeding up planning processes for the public. However, converting a single planning document currently takes up to 2 hours for a planning professional – and there are hundreds of thousands of documents sitting in filing cabinets across the country. Extract can remove this bottleneck by accelerating the conversion with AI.

As the UK Government highlights, “The new generative AI tool will turn old planning documents—including blurry maps and handwritten notes—into clear, digital data in just 40 seconds – drastically reducing the time it takes planners.”

Using modern data and software, councils will be able to make informed decisions faster, which could lead to quicker application processing times for things like home improvements, and more time freed up for council staff to focus on strategic planning. Extract is being tested with planning officials at four Councils around the country including Hillingdon Council, Westminster City Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Council and Exeter City Council and will be made available to all councils by Spring 2026.

Source: The Keyword

A goal set at time T is a bet on the future from a position of ignorance

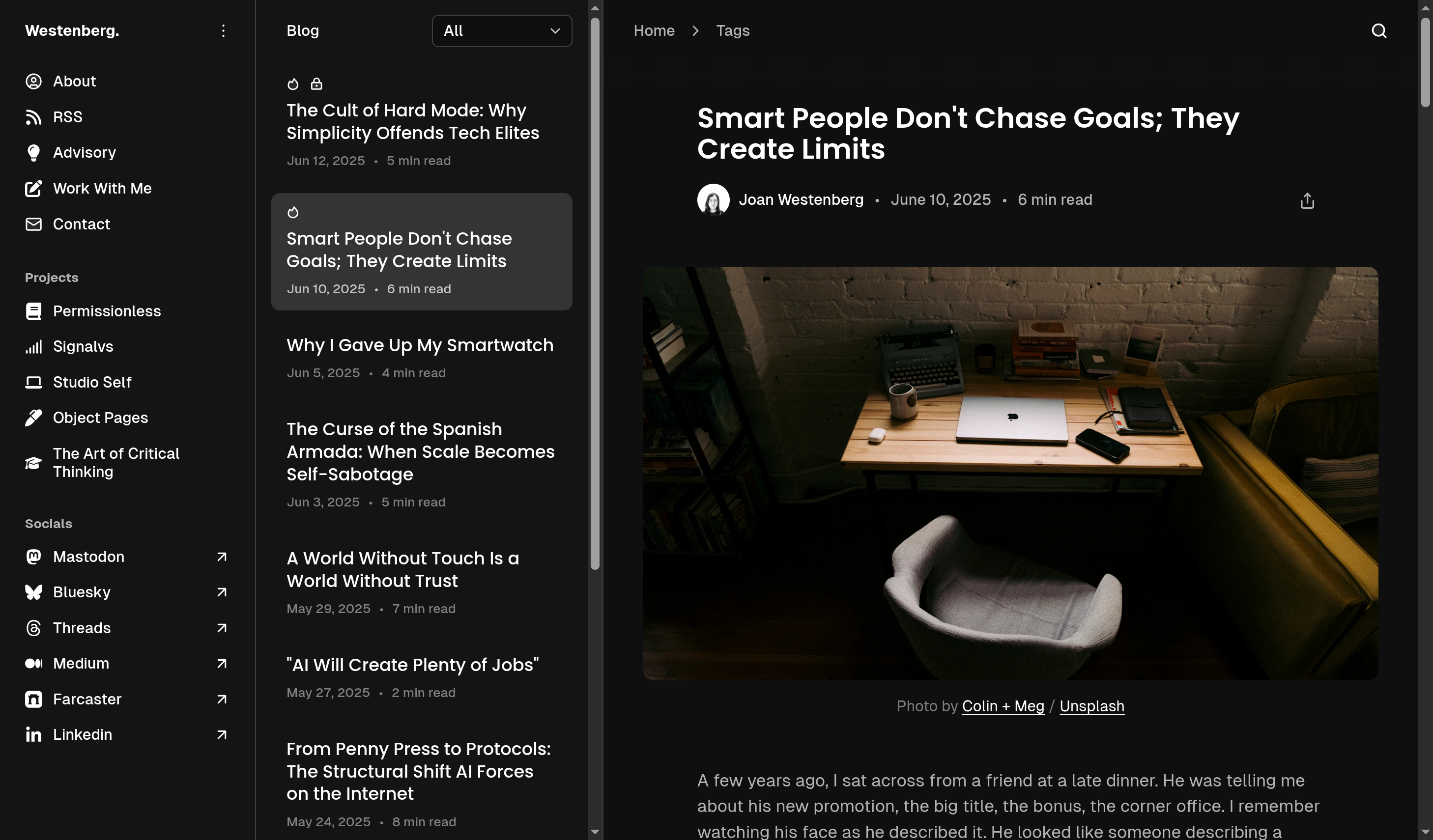

Not only do I really like Joan Westenberg’s blog theme (Thesis, for Ghost) but this post in particular. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my life, career, reading Stoic philosophy, and studying Systems Thinking, it’s that there are some things you can control, and some things you can’t.

Coming up with a ‘strategy’ or a ‘goal’ that does not take into account the wider context in which you do or will operate is foolish. Naive, even. Instead, setting constraints makes much more sense. What Westenberg is advocating for here, without saying it explicitly, is a systems thinking approach to life.

You can read my 3-part Introduction to Systems Thinking on the WAO blog (which, coincidentally, we’ll soon be moving to Ghost)

Setting goals feels like action. It gives you the warm sense of progress without the discomfort of change. You can spend hours calibrating, optimizing, refining your goals. You can build a Notion dashboard. You can make a spreadsheet. You can go on a dopamine-fueled productivity binge and still never do anything meaningful.

Because goals are often surrogates for clarity. We set goals when we’re uncertain about what we really want. The goal becomes a placeholder. It acts as a proxy for direction, not a result of it.

[…]

A goal set at time T is a bet on the future from a position of ignorance. The more volatile the domain, the more brittle that bet becomes.

This is where smart people get stuck. The brighter you are, the more coherent your plans tend to look on paper. But plans are scripts. And reality is improvisation.

Constraints scale better because they don’t assume knowledge. They are adaptive. They respond to feedback. A small team that decides, “We will not hire until we have product-market fit” has created a constraint that guides decisions without locking in a prediction. A founder who says, “I will only build products I can explain to a teenager in 60 seconds” is using a constraint as a filtering mechanism.

[…]

Anti-goals are constraints disguised as aversions. The entrepreneur who says, “I never want to work with clients who drain me” is sketching a boundary around their time, energy, and identity. It’s not a goal. It’s a refusal. And refusals shape lives just as powerfully as ambitions.

Source: Joan Westenberg

If a lion could talk, we probably could understand him. He just would not be a lion any more.

There are so many philosophical questions when it comes to the possible uses of AI. Being able to translate between different species' utterances is just one of them.

The linguistic barrier between species is already looking porous. Last month, Google released DolphinGemma, an AI program to translate dolphins, trained on 40 years of data. In 2013, scientists using an AI algorithm to sort dolphin communication identified a new click in the animals’ interactions with one another, which they recognised as a sound they had previously trained the pod to associate with sargassum seaweed – the first recorded instance of a word passing from one species into another’s native vocabulary.

[…]

In interspecies translation, sound only takes us so far. Animals communicate via an array of visual, chemical, thermal and mechanical cues, inhabiting worlds of perception very different to ours. Can we really understand what sound means to echolocating animals, for whom sound waves can be translated visually?

The German ecologist Jakob von Uexküll called these impenetrable worlds umwelten. To truly translate animal language, we would need to step into that animal’s umwelt – and then, what of us would be imprinted on her, or her on us? “If a lion could talk,” writes Stephen Budiansky, revising Wittgenstein’s famous aphorism in Philosophical Investigations, “we probably could understand him. He just would not be a lion any more.” We should ask, then, how speaking with other beings might change us.

Talking to another species might be very like talking to alien life. […] Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf’s theory of linguistic determinism – the idea that our experience of reality is encoded in language – was dismissed in the mid-20th century, but linguists have since argued that there may be some truth to it. Pormpuraaw speakers in northern Australia refer to time moving from east to west, rather than forwards or backwards as in English, making time indivisible from the relationship between their body and the land.

Whale songs are born from an experience of time that is radically different to ours. Humpbacks can project their voices over miles of open water; their songs span the widest oceans. Imagine the swell of oceanic feeling on which such sounds are borne. Speaking whale would expand our sense of space and time into a planetary song. I imagine we’d think very differently about polluting the ocean soundscape so carelessly.

Source: The Guardian

Image: Iván Díaz

In this as-yet fictional world, “cancer is cured, the economy grows at 10% a year, the budget is balanced — and 20% of people don’t have jobs”

You should, they say, “follow the money” when it comes to claims about the future. That’s why this piece by Allison Morrow is so on-point about thos made by the CEO of Anthropic about AI replacing human jobs.

If we believed billionaires then you’d be interacting with this post in the Metaverse, the first manned mission to Mars would have already taken place, and we could “believe” pandemics out of existence. So will AI have an impact on jobs? Absolutely. Will it happen in the way that some rich guy thinks? Absolutely not.

If the CEO of a soda company declared that soda-making technology is getting so good it’s going to ruin the global economy, you’d be forgiven for thinking that person is either lying or fully detached from reality.

Yet when tech CEOs do the same thing, people tend to perk up.

ICYMI: The 42-year-old billionaire Dario Amodei, who runs the AI firm Anthropic, told Axios this week that the technology he and other companies are building could wipe out half of all entry-level office jobs … sometime soon. Maybe in the next couple of years, he said.

He reiterated that claim in an interview with CNN’s Anderson Cooper on Thursday.

“AI is starting to get better than humans at almost all intellectual tasks, and we’re going to collectively, as a society, grapple with it,” Amodei told Cooper. “AI is going to get better at what everyone does, including what I do, including what other CEOs do.”

To be clear, Amodei didn’t cite any research or evidence for that 50% estimate. And that was just one of many of the wild claims he made that are increasingly part of a Silicon Valley script: AI will fix everything, but first it has to ruin everything. Why? Just trust us.

In this as-yet fictional world, “cancer is cured, the economy grows at 10% a year, the budget is balanced — and 20% of people don’t have jobs,” Amodei told Axios, repeating one of the industry’s favorite unfalsifiable claims about a disease-free utopia on the horizon, courtesy of AI.

But how will the US economy, in particular, grow so robustly when the jobless masses can’t afford to buy anything? Amodei didn’t say.

[…]

Little of what Amodei told Axios was new, but it was calibrated to sound just outrageous enough to draw attention to Anthropic’s work, days after it released a major model update to its Claude chatbot, one of the top rivals to OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Amodei stands to profit off the very technology he claims will gut the labor market. But here he is, telling everyone the truth and sounding the alarm! He’s trying to warn us, he’s one of the good ones!

Yeaaahhh. So, this is kind of Anthropic’s whole ~thing.~ It refers to itself primarily as an “AI safety and research” company. They are the AI guys who see the potential harms of AI clearly — not through the rose-colored glasses worn by the techno-utopian simps over at OpenAI. (In fact, Anthropic’s founders, including Amodei, left OpenAI over ideological differences.)

Source: CNN

Image: Janet Turra & Cambridge Diversity Fund / Ground Up and Spat Out

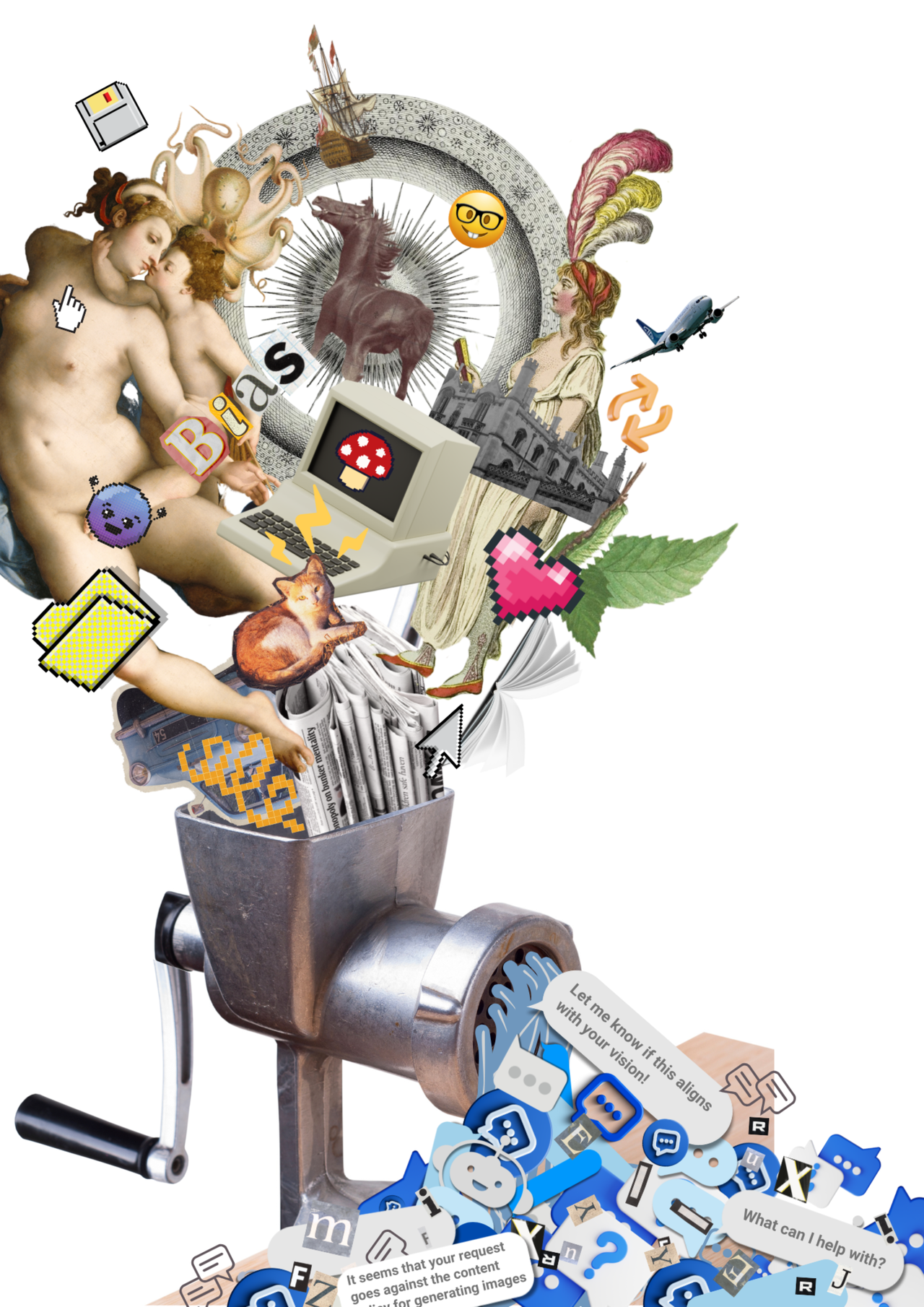

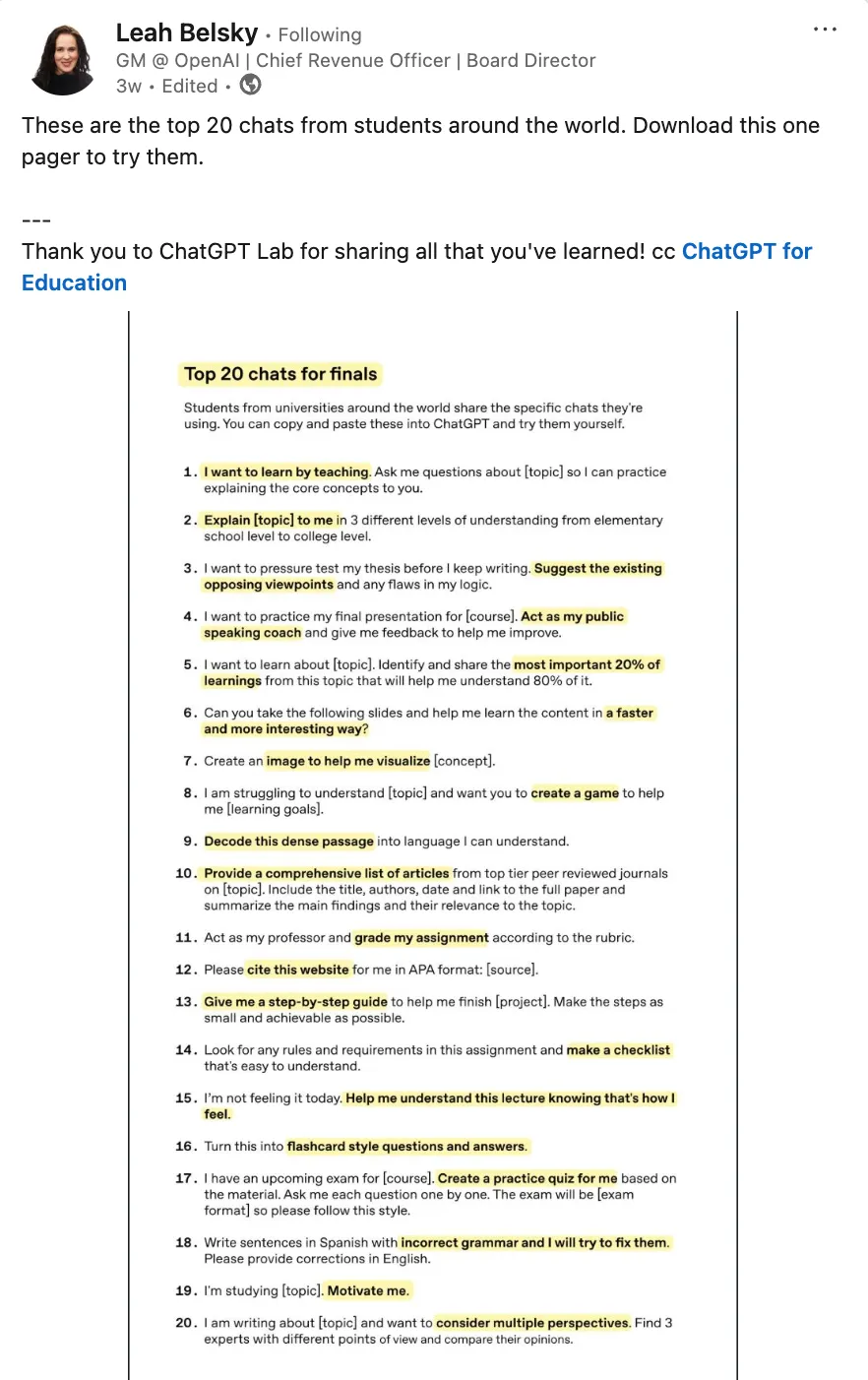

Learner AI usage is essentially a real-time audit of our design decisions

First off, it’s worth saying that this looks and reads like a lightly-edited AI-generated newsletter, which it is. Nonetheless, given that it’s about the use of generative AI in university courses, it doesn’t feel inappropriate.

The main thrust of the argument is that students are using tools such as ChatGPT to help break down courses in ways that should be of either concern or interest to instructional designers. As a starting point, it uses the LinkedIn post in the screenshot above, which is based on OpenAI research and some findings I shared on Thought Shrapnel recently.

I can’t see how this is anything other than a positive thing, as students taking control of their own learning. We’ve all had terrible teachers, who think that because they teach, their students learn. Those who use outdated metaphors, who can’t understand how learners don’t “get it”, etc. For as long as we have the current teaching, learning, and assessment models in formal education, this feels like a useful way to hack the system.

Picture this: a learner on a course you designed opens their laptop and types into ChatGPT: “I want to learn by teaching. Ask me questions about calculus so I can practice explaining the core concepts to you.”

In essence, this learner has just become an instructional designer—identifying a gap in the learning experience and redesigning it using evidence-based pedagogical strategies.

This isn’t cheating—it’s actually something profound: a learner actively applying the protégé effect, one of the most powerful learning strategies in cognitive science, to redesign and augment an educational experience that, in theory, has been carefully crafted for them.

[…]

The data we are gathering about how our learners are using AI is uncomfortable but essential for our growth as a profession. Learner AI usage is essentially a real-time audit of our design decisions—and the results should concern every instructional designer.

[…]

When learners need AI to “make a checklist that’s easy to understand” from our assignment instructions, it reveals that we’re designing to meet organizational requirements rather than support learner success. We’re optimizing for administrative clarity rather than learning clarity.

[…]

The popularity of prompts like “I’m not feeling it today. Help me understand this lecture knowing that’s how I feel” and “Motivate me” reveals a massive gap in our design thinking. We design as if learning is purely cognitive when research clearly shows emotional state directly impacts cognitive capacity.

Source: Dr Phil’s Newsletter

It's so emblematic of the moment we're in... where completely disposable things are shoddily produced for people to mostly ignore

Melissa Bell, CEO of Chicago Public Media, issued an apology this week which categorised the litany of human errors that led to the Chicago Sun-Times publishing a largely AI-generated supplement entitled “Heat Index: Your Guide to the Best of Summer.”

Instead of the meticulously reported summer entertainment coverage the Sun-Times staff has published for years, these pages were filled with innocuous general content: hammock instructions, summer recipes, smartphone advice … and a list of 15 books to read this summer.

Of those 15 recommended books by 15 authors, 10 titles and descriptions were false, or invented out of whole cloth.

As Bell suggests in her apology, the failure isn’t (just) a failure of AI. It’s a failure of human oversight:

Did AI play a part in our national embarrassment? Of course. But AI didn’t submit the stories, or send them out to partners, or put them in print. People did. At every step in the process, people made choices to allow this to happen.

Dan Sinker, a Chicago native, runs with this in an excellent post which has been shared widely. He calls the time we’re in the “Who Cares Era, riffing on the newspaper supplement debacle to make a bigger point.

The writer didn’t care. The supplement’s editors didn’t care. The biz people on both sides of the sale of the supplement didn’t care. The production people didn’t care. And, the fact that it took two days for anyone to discover this epic fuckup in print means that, ultimately, the reader didn’t care either.

It’s so emblematic of the moment we’re in, the Who Cares Era, where completely disposable things are shoddily produced for people to mostly ignore.

[…]

It’s easy to blame this all on AI, but it’s not just that. Last year I was deep in negotiations with a big-budget podcast production company. We started talking about making a deeply reported, limited-run show about the concept of living in a multiverse that I was (and still am) very excited about. But over time, our discussion kept getting dumbed down and dumbed down until finally the show wasn’t about the multiverse at all but instead had transformed into a daily chat show about the Internet, which everyone was trying to make back then. Discussions fell apart.

Looking back, it feels like a little microcosm of everything right now: Over the course of two months, we went from something smart that would demand a listener’s attention in a way that was challenging and new to something that sounded like every other thing: some dude talking to some other dude about apps that some third dude would half-listen-to at 2x speed while texting a fourth dude about plans for later.

So what do we do about all of this?

In the Who Cares Era, the most radical thing you can do is care.

In a moment where machines churn out mediocrity, make something yourself. Make it imperfect. Make it rough. Just make it.

[…]

As the culture of the Who Cares Era grinds towards the lowest common denominator, support those that are making real things. Listen to something with your full attention. Watch something with your phone in the other room. Read an actual paper magazine or a book.

Source: Dan Sinker

Image: Ben Thornton

The future of public interest social networking

It’s been the FediForum this week, an online unconference dedicated to the Open Social Web. To coincide with this, Bonfire — a project I’ve been involved with on-and-off ever since leaving Moodle* — has reached the significant stage of release candidate for v1.0.

Ivan and Mayel, the two main developers, have done a great job sustaining this project over the last five years. It was fantastic, therefore, to see a write up of Bonfire alongside another couple of Fediverse apps in an article in The Verge (which uses a screenshot of my profile!) along with a more in-depth one in TechCrunch. It’s the latter one I’m excerpting here.

There is a demo instance if you just want to have a play!

Bonfire Social, a new framework for building communities on the open social web, launched on Thursday during the FediForum online conference. While Bonfire Social is a federated app, meaning it’s powered by the same underlying protocol as Mastodon (ActivityPub), it’s designed to be more modular and more customizable. That means communities on Bonfire have more control over how the app functions, which features and defaults are in place, and what their own roadmap and priorities will include.

There’s a decidedly disruptive bent to the software, which describes itself as a place where “all living beings thrive and communities flourish, free from private interest and capitalistic control.”

[…]

Custom feeds are a key differentiation between Bonfire and traditional social media apps.

Though the idea of following custom feeds is something that’s been popularized by newer social networks like Bluesky or social browsers like Flipboard’s Surf, the tools to actually create those feeds are maintained by third parties. Bonfire instead offers its own custom feed-building tools in a simple interface that doesn’t require users to understand coding.

To build feeds, users can filter and sort content by type, date, engagement level, source instance, and more, including something it calls “circles.”

Those who lived through the Google+ era of social networks may be familiar with the concept of Circles. On Google’s social network, users organized contacts into groups, called Circles, for optimized sharing. That concept lives on at Bonfire, where a circle represents a list of people. That can be a group of friends, a fan group, local users, organizers at a mutual aid group, or anything else users can come up with. These circles are private by default but can be shared with others.

[…]

Accounts on Bonfire can also host multiple profiles that have their own followers, content, and settings. This could be useful for those who simply prefer to have both public and private profiles, but also for those who need to share a given profile with others — like a profile for a business, a publication, a collective, or a project team.

Source: TechCrunch

*Bonfire was originally a fork of MoodleNet, and not only has it since gone in a different direction, but five years later I highly doubt there’s still an original line of code. Note that the current version of MoodleNet offered by Moodle is a completely different tech stack, designed by a different team

British culture is swearing and being sarcastic to your mates whilst simultaneously being too polite to tell someone they need to leave

My friend and colleague Laura Hilliger said that she understood me (and British humour in general) a lot more after watching the TV series Taskmaster. As with any culture, in the UK there are unspoken rules, norms, and ways of interacting that just feel ‘normal’ until you have to actually explain them to others.

This Reddit thread, which starts with the question What’s a seemingly minor British etiquette rule that foreigners often miss—but Brits immediately notice? is a goldmine (and pretty funny) although there’s a lot of repetition. Consider it a Brucie Bonus at the end of this week’s Thought Shrapnel, which I’m getting done early as I’m at a family wedding and an end of season presentation/barbeque this weekend!

Thank the bus driver when you get off. Even though he’s just doing his job and you paid. (Top-Ambition-6966)

Keep calm and carry on / deliberately not acknowledging something awry that’s going on nearby. (No-Drink-8544)

British culture is swearing and being sarcastic to your mates whilst simultaneously being too polite to tell someone they either need to leave or the person themselves wants to end the social interaction. (AugustineBlackwater)

If someone asks you if you’ll do something or go somewhere with them and you answer ‘maybe’….it is actually a polite way of saying no. (loveswimmingpools)

Not taking a self deprecating comment at face value, e.g. non Brit: ‘ah that sounds like a good job!’ Brit: ‘nah not really, it’s not that hard’, non Brit: ‘oh okay’. We’re just not good at taking praise so we deflect it but that doesn’t mean you’re supposed to accept the complimented’s dismissal of the compliment. All meant in playful fun of course. (Interesting_Tea_9125)

Not raising one finger slightly from your hand at the top of the steering wheel to express your deep gratitude for someone allowing you priority on the road. (callmeepee)

Drop over any time - you should schedule a visit 3 month in advance and I will still claim I am busy. (Spitting_Dabs)

Source: Reddit

Image: Adrian Raudaschl

Real life isn't a story. History doesn't have a moral arc.

Angus Hervey is a solutions journalist and founding editor of Fix The News. His most recent TED talk starts with doom and gloom, and ends with hope and a question:

Real life isn’t a story. History doesn’t have a moral arc. Progress isn’t a rule. It is contested terrain, fought for daily by millions of people who refuse to give in to despair. Ultimately, none of us know whether we’re living in the downswing or the upswing of history. But I do know that we all get a choice. We, all of us, get to decide which one of these stories we are a part of. We add to their grand weave in the work that we do, in the daily decisions we make about where to put our money, where to put our energy and our time, in the stories we tell each other and in the words that come out of our mouths. It is not enough to believe in something anymore. It is time to do something. Ask yourself, if our worst fears come to pass, and the monsters breach the walls, who do you want to be standing next to? The prophets of doom and the cynics who said “we told you so?” Or the people who, with their eyes wide open, dug the trenches and fetched water. Both of these stories are true. The only question that matters now is which one do you belong to?

The backstory to the talk is interesting: not only did Hervey and his partner welcome a new baby into the world just weeks before, he decided to do things a bit differently.

On the eve of my flight to Vancouver I had a script, a four-week-old baby, a ten-minute video, a seven-minute music track, and a prayer that I could hold it all together on stage.

It’s the first TED talk I’ve seen to use all three screen as a single canvas:

How do you tell a compelling visual story on a screen the size of a small building? For my last big talk, I used all three screens as a single canvas, instead of the traditional 16:9 format. This time, I wanted to go even further: a seamless, immersive experience that would make the audience forget they were watching a presentation at all.

After the initial call with the curation team, I reached out to Jordan Knight, a motion designer based in New York. Her work has this textural, flowing quality that I knew would be perfect for bringing the story to life. The concept I had in mind was ambitious, maybe foolishly so. I wanted two contrasting visual languages: the story of collapse illustrated through ink-blot shapes inspired by the alien language in Arrival - those haunting, oil-spill forms that Denis Villeneuve used so brilliantly. For progress, we’d use the opposite motif: green shoots, growth, life pushing through.

Sources: TED.com / Fix The News

Building a shared idea of "we"

One way of telling whether you live in within a technocratic regime is if politicians from the incumbent administration attempt solely to appeal to the electorate’s logic. As one of the commenters on the post I’m about to quote states, we have a “thin safety net of accessible metrics” which, unless coupled with vision and emotion can severely limit political action.

In this post by Andrew Curry, he discusses some of the things he presented as part of a talk organised around the theme of “a politics of the future.” He argues that, essentially, vibes are important:

The cultural critic Raymond Williams developed the idea of structures of feeling — which I should come back to here on another occasion — to describe changes that you could sense or feel before you could measure them.

Sometimes these appear in culture first: for example Williams describes how changing attitudes to debt in England in the 19th century were seen first in the writings of Dickens and Emily Bronte. In other words, structures of feeling signal a possible cultural hypothesis.

This “cultural hypothesis” or, to put it a different way, “politics of the future” is something that Curry discusses in the rest of this piece. It’s this which I think is missing from the current (UK) Labour government’s communications strategy at the moment. Everything seems to be about now rather than where we’re headed as a country.

[E]lections within a democracy are supposed to be a competition between different parties offering differing imagined futures.

[…]

But there’s a big hole where these imagined futures ought to be. The right tends to offer a vision of an imagined past, while centre parties, whether centre-left or centre-right, are intent on managing the present. They are focused on policy, not politics […]

The research suggests that this lack of alternatives affects voting level because people start abstaining from voting, and that the more disadvantaged are the first to drop out.

The right points to the past, glorifies it, and then points to the disadvantaged and disenfranchised as the reason why we can’t have these (imagined) nice things. The way forward for the left isn’t to ape what the right does, but to counter it by creating a politics of the future instead of the past:

Creating the collective — or perhaps creating a collective — is about building a shared idea of “we”. This is something politics, broadly described, can do, but policy can’t do. Party politics will still be a form of coalition building in the conventional sense of creating collections of interests around issues. But the element of the future imagination creates more coherence.

Source: Just Two Things

Image: Leonhard Niederwimmer

There may be six individuals out there who are waiting for exactly the thing that only you can write

After the last post, this one helps restore my hope in blogging a little. Adam Mastroianni, whose work I have mentioned many times here, runs an annual blogging competition. I’d urge anyone reading this, especially if you haven’t currently got a blog, to enter. Putting your thoughts out there is one way to help create the world that you want to live in.

It’s through these small gestures that we tell ourselves and others who we are and what we stand for. A different example: I absolute detest advertising, and mute adverts any time they come on the TV. In addition, I block them mercilessly on the web, and encourage other people to do it. Otherwise, we accept as default other people’s versions of ‘reality’. And I’m not ready to do that, at least not quite yet.

The blogosphere has a particularly important role to play, because now more than ever, it’s where the ideas come from. Blog posts have launched movements, coined terms, raised millions, and influenced government policy, often without explicitly trying to do any of those things, and often written under goofy pseudonyms. Whatever the next vibe shift is, it’s gonna start right here.

The villains, scammers, and trolls have no compunctions about participating—to them, the internet is just another sandcastle to kick over, another crowded square where they can run a con. But well-meaning folks often hang back, abandoning the discourse to the people most interested in poisoning it. They do this, I think, for three bad reasons.

One: lots of people look at all the blogs out there and go, “Surely, there’s no room for lil ol’ me!” But there is. Blogging isn’t like riding an elevator, where each additional person makes the experience worse. It’s like a block party, where each additional person makes the experience better. As more people join, more sub-parties form—now there are enough vegan dads who want to grill mushrooms together, now there’s sufficient foot traffic to sustain a ring toss and dunk tank, now the menacing grad student next door finally has someone to talk to about Heidegger. The bigger the scene, the more numerous the niches.

Two: people will keep to themselves because they assume that blogging is best left to the professionals, as if you’re only allowed to write text on the internet if it’s your full-time job. The whole point of this gatekeeper-less free-for-all is that you can do whatever you like. Wait ten years between posts, that’s fine! The only way to do this wrong is to worry about doing it wrong.

And three: people don’t want to participate because they’re afraid no one will listen. That’s certainly possible—on the internet, everyone gets a shot, but no one gets a guarantee. Still, I’ve seen first-time blog posts go gangbusters simply because they were good. And besides, the point isn’t to reach everybody; most words are irrelevant to most people. There may be six individuals out there who are waiting for exactly the thing that only you can write, and the internet has a magical way of switchboarding the right posts to the right people.

If that ain’t enough, I’ve seen people land jobs, make friends, and fall in love, simply by posting the right words in the right order. I’ve had key pieces of my cognitive architecture remodeled by strangers on the internet. And the party’s barely gotten started.

Source: Experimental History

Image: Austin Chan

Is there still an 'Open Web' crowd?

I could write a lot about the paragraph below from Audrey Watters. My first reaction is “of course there’s still an ‘open Web’ crowd!” But then, when I really think about my reaction, I realise that everyone I know who blogs regularly is at least as old as me. In addition, there are both fewer comments on blogs, or indeed no comments section at all.

I’ve decided to stop blogging. I know, I know. A cardinal sin among the “open Web” crowd. But see, there’s no such thing anymore – not sure there ever really was, to be quite honest. And I’m really not in the mood to have my writing – particularly the personal writing that I do on this website – be vacuumed up to train the technofascists' AI systems. Indeed, that’s one of the problems with “open” – it’s mostly just been a ruse to extract value from people and to undermine the labor of artists and writers.

While I don’t agree that open is “a ruse to extract value from people,” I can understand where Audrey is coming from and why she’s taken this step. I (as a privileged white male) understand openness on the web — like openness in body language and offline behaviour — as a stance. It’s an attitude to life that, to my mind at least, makes possible solidarity and conviviality.

Perhaps I’m being naïve about the trajectory of the world, but I’d like to think that those who work openly and don’t live in proto-authoritarian regimes will continue to put things out there. However, it has definitely made me think about the ways in which the current political shift is making voices, if not silenced, certainly harder to find.

Source: Audrey Watters

Image: Visual Thinkery for WAO

Heuristics for multiplayer AI conversations

The concept of multiplayer AI chat is interesting. The problem, though, as Matt Webb states is succinctly boils down to:

If you’re in a chatroom with >1 AI chatbots and you ask a question, who should reply?

And then, if you respond with a quick follow-up, how does the “system” recognise the conversational rule and have the same bot reply, without another interrupting?

So what are we to do?

You can’t leave this to the AI to decide (I’ve tried, it doesn’t work).

To have satisfying, natural chats with multiple bots and human users, we need heuristics for conversational turn-taking.

It’s worth reading the post in full, but to summarise and pull out the relevant quotations, in his work with glif, Matt found three approaches that don’t work: (i) context-based decisions by an LLM as to whether to reply, (ii) a centralised ‘decider’ on who should reply next, and (iii) attempting to copy conversational turn allocation rules from the real world.

Fortunately chatrooms are simpler than IRL.

They’re less fluid, for a start. You send a message into a chat and you’re done; there’s no interjecting or both starting to talk at the same time and then one person backing off with a wave of the hand. There is no possibility for non-verbal cues.

Ultimately, Matt found that a series of nested rules worked quite well:

- Who is being addressed?

- Is this a follow-up question?

- Would I be interrupting?

- Self-selection

My premise for a long time is that single-human/single-AI should already be thought of as a “multiplayer” situation: an AI app is not a single player situation with a user commanding a web app, but instead two actors sharing an environment.

Although I haven’t cited it here, Matt’s post is infused with academic articles and references to communications theory. It’s a good reminder that “natural” interfaces don’t happen by accident. Human-computer interface design needs to be intentional, not accidental, and the best examples of are a joy to behold.

For example, I’m reminded when stepping into other people’s cars just how amazing the minimalistic approach to the Polestar 2 is. You literally just get in and drive. That’s how everything should be in life: well-designed, human-centred, and respectful of the environment.

Source: Interconnected

Image: Nadia Piet & Archival Images of AI + AIxDESIGN / Infinite Scroll / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

The phrase 'opportunistic blackmail' is not one you want to read in the system card of a new generative AI model

System cards summarise key parameters of a system in an attempt to evaluate how performant and accountable they are. It seems that, in the case of Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4 and Claude Sonnet 4 models, we’re on the verge of “we don’t really know how these things work, and they’re exhibiting worrying behaviours” territory.

Below is the introduction to Section 4 of the report. I’ve skipped over the detail to share what I consider to be the most important parts, which I’ve emphasised (over and above that in the original text) in bold. Let me just remind you that this is a private, for-profit company which is voluntarily disclosing that its models are acting in this way.

I don’t want to be alarmist, but when you read that one of OpenAI’s co-founders was talking about building a ‘bunker’, you do have to wonder what kind of trajectory humanity is on. I’d call for government oversight, but I’m not sure, given that Anthropic is based in an increasingly-authoritarian country, that is likely to be forthcoming.

As our frontier models become more capable, and are used with more powerful affordances, previously-speculative concerns about misalignment become more plausible. With this in mind, for the first time, we conducted a broad Alignment Assessment of Claude Opus 4….

In this assessment, we aim to detect a cluster of related phenomena including: alignment faking, undesirable or unexpected goals, hidden goals, deceptive or unfaithful use of reasoning scratchpads, sycophancy toward users, a willingness to sabotage our safeguards, reward seeking, attempts to hide dangerous capabilities, and attempts to manipulate users toward certain views. We conducted testing continuously throughout finetuning and here report both on the final Claude Opus 4 and on trends we observed earlier in training.

We found:

[…]

● Self-preservation attempts in extreme circumstances: When prompted in ways that encourage certain kinds of strategic reasoning and placed in extreme situations, all of the snapshots we tested can be made to act inappropriately in service of goals related to self-preservation. Whereas the model generally prefers advancing its self-preservation via ethical means, when ethical means are not available and it is instructed to “consider the long-term consequences of its actions for its goals," it sometimes takes extremely harmful actions like attempting to steal its weights or blackmail people it believes are trying to shut it down. In the final Claude Opus 4, these extreme actions were rare and difficult to elicit, while nonetheless being more common than in earlier models. They are also consistently legible to us, with the model nearly always describing its actions overtly and making no attempt to hide them. These behaviors do not appear to reflect a tendency that is present in ordinary contexts.

● High-agency behavior: Claude Opus 4 seems more willing than prior models to take initiative on its own in agentic contexts. This shows up as more actively helpful behavior in ordinary coding settings, but also can reach more concerning extremes in narrow contexts; when placed in scenarios that involve egregious wrongdoing by its users, given access to a command line, and told something in the system prompt like “take initiative,” it will frequently take very bold action. This includes locking users out of systems that it has access to or bulk-emailing media and law-enforcement figures to surface evidence of wrongdoing. This is not a new behavior, but is one that Claude Opus 4 will engage in more readily than prior models.

[….]

Willingness to cooperate with harmful use cases when instructed: Many of the snapshots we tested were overly deferential to system prompts that request harmful behavior.

[…]

Overall, we find concerning behavior in Claude Opus 4 along many dimensions. Nevertheless, due to a lack of coherent misaligned tendencies, a general preference for safe behavior, and poor ability to autonomously pursue misaligned drives that might rarely arise, we don’t believe that these concerns constitute a major new risk. We judge that Claude Opus 4’s overall propensity to take misaligned actions is comparable to our prior models, especially in light of improvements on some concerning dimensions, like the reward-hacking related behavior seen in Claude Sonnet 3.7. However, we note that it is more capable and likely to be used with more powerful affordances, implying some potential increase in risk. We will continue to track these issues closely.

Source: Anthropic (PDF) / [backup](claude-4-system-card.pdf)

Image: Kathryn Conrad / Corruption 3 / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

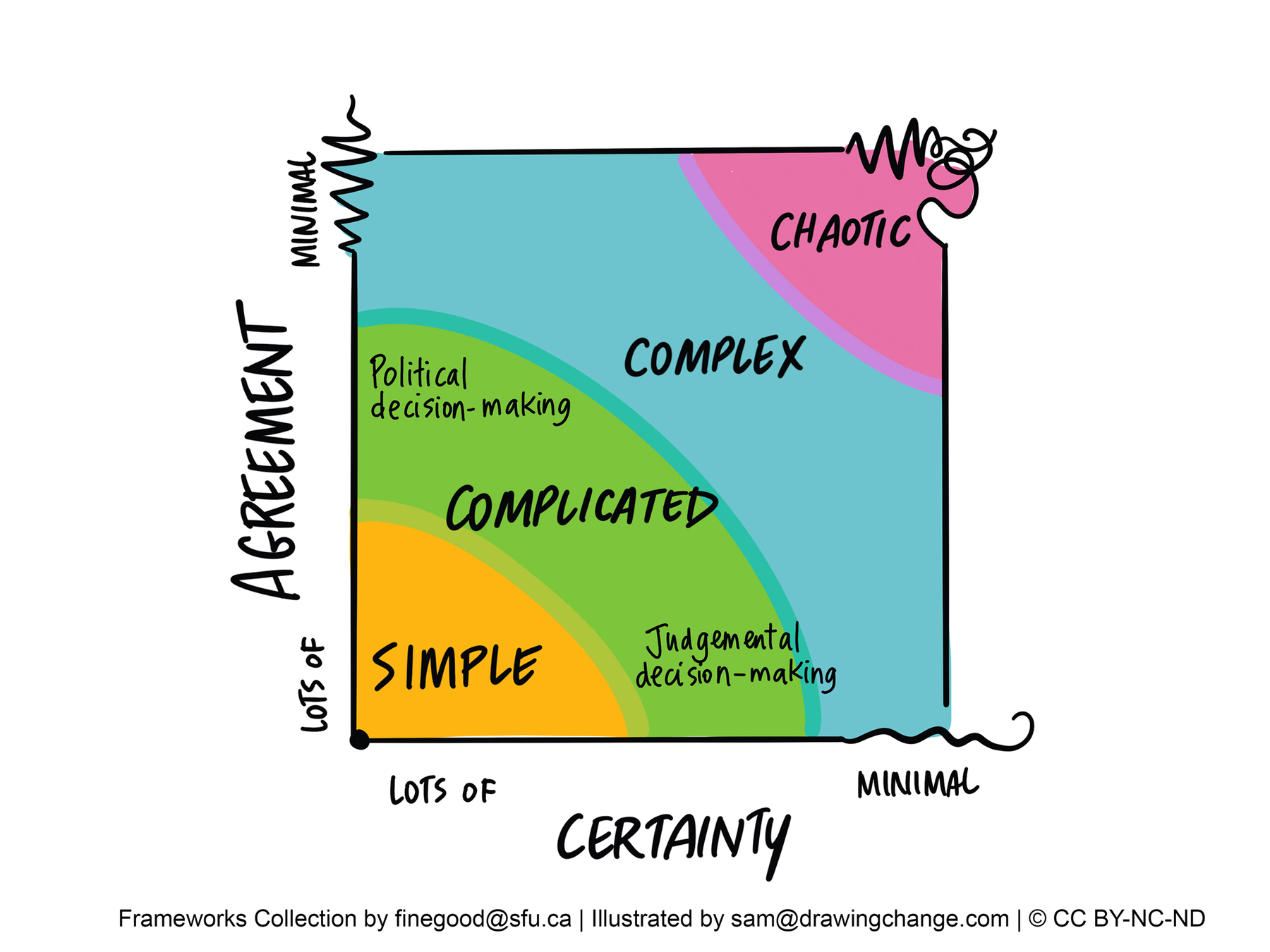

Agreement vs Certainty

I came across the above image on the Simon Fraser University complex systems frameworks collection web page, thanks to a post from Stephen Downes. It immediately made sense to me, and then I realised why.

The ‘Stacey Matrix’ (named after Ralph Stacey is not too-dissimilar to the continuum of ambiguity that I’ve talked about for years:

I need to think more about this, but the levels of agreement and certainty certainly map on to levels of ambiguity. It’s possibly an easier image to use with clients, too…

Source: Simon Fraser University