- Appoint someone as online executor

- State in a formal document how profiles and accounts are handled

- Understand privacy policies

- Provide online executor list of websites and logins

- State in the will that the online executor must have a copy of the death certificate

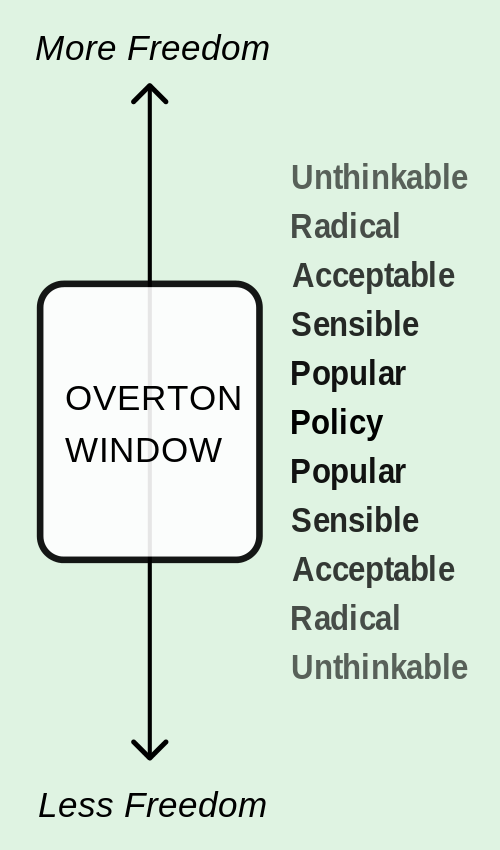

- Really important to my legacy

- Kind of important

- Not important

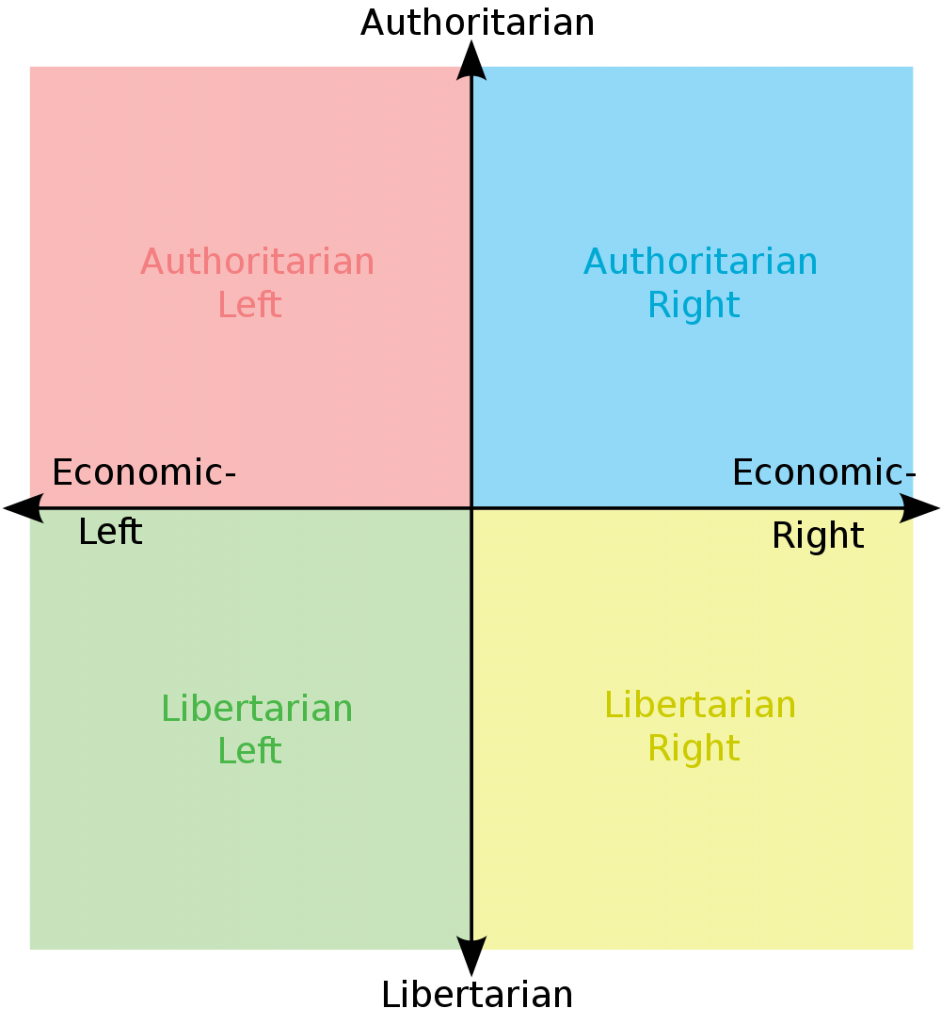

- Reactionary neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, within an exclusionary vision of a racist, patriarchal, and homophobic society.

- Progressive neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, while using the banner of 'diversity' to assimilate equality and meritocracy.

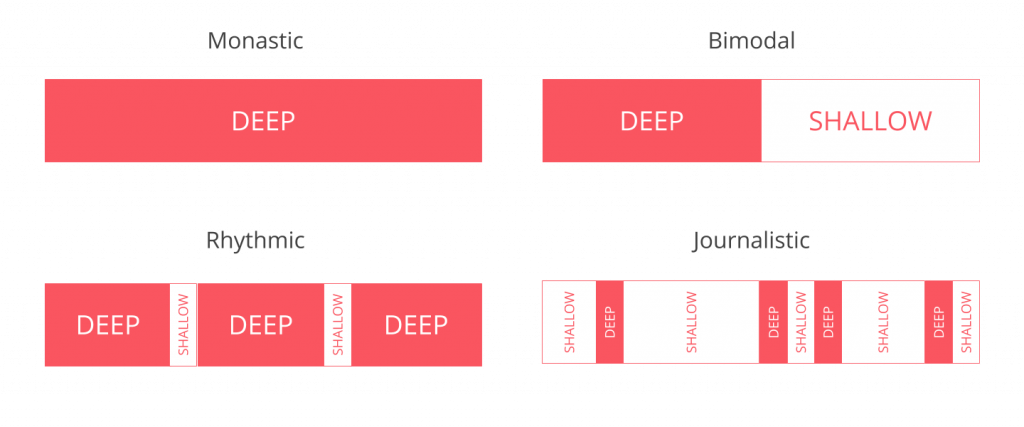

- More workers want to slow down to get things right — "In reality, 61% of workers said they wanted to “slow down to get things right” while only 41%* wanted to “go fast to achieve more.” The divide was even starker among older workers."

- Workers strongly value uninterrupted focus at work, but most will make an exception to help others — "The results suggest we need to be more thoughtful about when we break our concentration, or ask others to do so. When people know they are helping others in a meaningful way, they tend to be okay with some distraction. But the busywork of meetings, alerts, and emails can quickly disrupt a person’s flow—one of the most important values we polled."

- Most workers have slightly more trust in people closest to the work, rather than people in upper management — "Among all respondents, 53% trusted people “closest to the work,” while only 45% trusted “upper management.” You might assume that younger workers would be the most likely to trust peers over management, but in fact, the opposite was true."

- Workers are torn between idealism and pragmatism — "It’s tempting to assume that addressing just one piece—like taking a stand on societal issues—will necessarily get in the way of the work itself. But our research suggests we can begin to solve the two in tandem, as more equality, inclusion, and diversity tends to come hand-in-hand with a healthier mindset about work."

- Health effects of job insecurity (IZA) — "Workers’ health is not just a matter for employees and employers, but also for public policy. Governments should count the health cost of restrictive policies that generate unemployment and insecurity, while promoting employability through skills training."

- Will your organization change itself to death? (opensource.com) — "Sometimes, an organization returns to the same state after sensing a stimulus. Think about a kid's balancing doll: You can push it and it'll wobble around, but it always returns to its upright state... Resilient organizations undergo change, but they do so in the service of maintaining equilibrium."

- Your Brain Can Only Take So Much Focus (HBR) — "The problem is that excessive focus exhausts the focus circuits in your brain. It can drain your energy and make you lose self-control. This energy drain can also make you more impulsive and less helpful. As a result, decisions are poorly thought-out, and you become less collaborative."

- Say Hello to the World

- An Invitation to Earth

- Small Changes, Big Impact

- The Neutral Point of View

- The Veil of Verifiability

- The Civility Code

- Looking Good Together

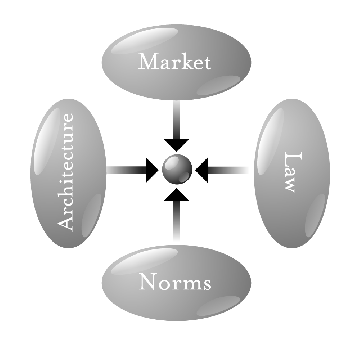

Four forces that constrain our actions

‘Pathetic Dot’ is not a great name for a theory, and the diagram on the Wikipedia page isn’t the best, but Christina Bowen reminded me of it during an introductory conversation yesterday.

I can’t find it again quickly, but this also reminds me of a discussion I saw about how credit scores can exert almost as much unseen social control over people in the West as very visible social control mechanisms in more authoritarian countries.

The pathetic dot theory or the New Chicago School theory was introduced by Lawrence Lessig in a 1998 article and popularized in his 1999 book, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace. It is a socioeconomic theory of regulation. It discusses how lives of individuals (the pathetic dots in question) are regulated by four forces: the law, social norms, the market, and architecture (technical infrastructure).Source: Pathetic dot theory | WikipediaLessig identifies four forces that constrain our actions: the law, social norms, the market, and architecture. The law threatens sanction if it is not obeyed. Social norms are enforced by the community. Markets through supply and demand set a price on various items or behaviors. The final force is the (social) architecture. By that Lessig means “features of the world, whether made, or found”; noting that facts like biology, geography, technology and others constrain our actions. Together, those four forces are the totality of what constrains our action, in fashion both direct and indirect, ex post and ex ante.

[…]

The theory can be applied to many aspects of life (such as how smoking is regulated), but it has been popularized by Lessig’s subsequent usage of it in the context of the regulation of the Internet.

Are we in a post-album era for music?

One of the downsides of getting older is that things you took to be sacred all of a sudden seem to be obsolete. For example, music albums, which have always been a part of my life, seem to now be referred to in the past tense?

There’s a whole Wikipedia article on the ‘album era’ so… it must be true.

The album era was a period in English-language popular music from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s in which the album was the dominant form of recorded music expression and consumption. It was primarily driven by three successive music recording formats: the 33⅓ rpm long-playing record (LP), the audiocassette, and the compact disc. Rock musicians from the US and the UK were often at the forefront of the era, which is sometimes called the album-rock era in reference to their sphere of influence and activity. The term "album era" is also used to refer to the marketing and aesthetic period surrounding a recording artist's album release.Source: Album era | Wikipedia

Nothing is repeated, and everything is unparalleled

🤔 We need more than deplatforming — "But as reprehensible as the actions of Donald Trump are, the rampant use of the internet to foment violence and hate, and reinforce white supremacy is about more than any one personality. Donald Trump is certainly not the first politician to exploit the architecture of the internet in this way, and he won’t be the last. We need solutions that don’t start after untold damage has been done."

💪 Demands and Responsibilities — "If you demand rights for yourself, you have to demand those same rights for others. You have to take on the responsibility of collective action, and you yourself act in a way that benefits the collective. If you want credit, you have to give credit. If you want community, you have to be communal. If you want to be satiated, you have to allow others to be sated. If you want your vote to be respected, you have to respect the votes of others."

🗯️ Parler Pitched Itself as Twitter Without Rules. Not Anymore, Apple and Google Said. — "Google said in a statement that it had pulled the app because Parler was not enforcing its own moderation policies, despite a recent reminder from Google, and because of continued posts on the app that sought to incite violence."

🙅 Hello! You've Been Referred Here Because You're Wrong About Section 230 Of The Communications Decency Act — "While this may all feel kind of mean, it's not meant to be. Unless you're one of the people who is purposefully saying wrong things about Section 230, like Senator Ted Cruz or Rep. Nancy Pelosi (being wrong about 230 is bipartisan). For them, it's meant to be mean. For you, let's just assume you made an honest mistake -- perhaps because deliberately wrong people like Ted Cruz and Nancy Pelosi steered you wrong. So let's correct that."

🧐 What Wikipedia saw during election week in the U.S., and what we’re doing next — "To help meet this goal, we hope to invest in resources that we can share with international Wikipedia communities that will help mitigate future disinformation risks on the sites. We’re also looking to bring together administrators from different language Wikipedias for a global forum on disinformation. Together, we aim to build more tools to support our volunteer editors, and to combat disinformation."

Quotation-as-title by the Goncourt Brothers. Image from top-linked post.

There are persons who, when they cease to shock us, cease to interest us

It's difficult not to say "I told you so" when things play out exactly as predicted. Four years ago, when Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th President of the USA, many had ominous forebodings.

Donald Trump’s inaugural address was a declaration of war on everything represented by these choreographed civilities. President Trump – it’s time to begin to get used to those jarringly ill-fitting words – did not conjure a deathless phrase for the day. His words will not lodge in the brain in any of the various uplifting ways that the likes of Lincoln, Roosevelt, Kennedy or Reagan once achieved. But the new president’s message could not have been clearer. He came to shatter the veneer of unity and continuity represented by the peaceful handover. And he may have succeeded. In 1933, Roosevelt challenged the world to overcome fear. In 2017, Mr Trump told the world to be very afraid.

The Guardian view on Donald Trump’s inauguration: a declaration of political war (January 2017)

He was all bluster, we were told. That it was rhetoric and would never be followed up with action.

Leaders are judged by their first 100 days in office. Wikipedia has a page outlining what Trump did during his, including things that, looking back from the vantage point of 2021, seem like warning shots: rolling back gun control legislation, stoking fears around voter fraud, cracking down on illegal immigration, freezing federal job hiring (except military), and engaging in tax reform to the benefit of the rich.

As a History teacher, it always struck me as odd that Adolf Hitler, a man born in Austria with brown hair, managed to lead a fascist party that extolled the virtues of being German and having blond hair. These days, I'm equally baffled that some of the richest people in our society — Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees-Mogg — can pass themselves off as 'anti-elite'.

Much of their ability to do so is by creating an alternative reality with the aid of social networks like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. These replace traditional gatekeepers to information with algorithms tweaked for engagement, attention, and profit.

As we know, whipping up hatred and peddling conspiracy theories puts these algorithms into overdrive, and ensure those who agree with the content see what's shared. But this approach also reaches those who don't agree with it, by virtue of people seeking to reject and push back on it. Meanwhile, of course, the platforms rake in $$$ from advertisers.

I get the feeling that there are a great number of people who do not understand the way the world works in 2021. I am probably one of them. In fact, given how much control we've given to algorithms in recent years, perhaps no-one truly understands.

One thing for sure, though, is that banning Donald Trump from Facebook and Instagram indefinitely is too little, too late. These platforms, among with others, downplayed his and other 'alt-right' hate speech for fear of being penalised.

Pandora's Box is open. Those who realise that everything is a construct and theory-laden will control those who don't. The latter will be reduced to merely wandering around an alternative reality, like protesters in Statuary Hall, waiting to be told what to do next.

Quotation-as-title by F.H. Bradley

Why we can't have nice things

There's a phrase, mostly used by Americans, in relation to something bad happening: "this is why we can't have nice things".

I'd suggest that the reason things go south is usually because people don't care enough to fix, maintain, or otherwise care for them. That goes for everything from your garden, to a giant wiki-based encyclopedia that is used as the go-to place to check facts online.

The challenge for Wikipedia in 2020 is to maintain its status as one of the last objective places on the internet, and emerge from the insanity of a pandemic and a polarizing election without being twisted into yet another tool for misinformation. Or, to put it bluntly, Wikipedia must not end up like the great, negligent social networks who barely resist as their platforms are put to nefarious uses.

Noam Cohen, Wikipedia's Plan to Resist Election Day Misinformation (WIRED)

Wikipedia's approach is based on a evolving process, one that is the opposite of "go fast and break things".

Moving slowly has been a Wikipedia super-power. By boringly adhering to rules of fairness and sourcing, and often slowly deliberating over knotty questions of accuracy and fairness, the resource has become less interesting to those bent on campaigns of misinformation with immediate payoffs.

Noam Cohen, Wikipedia's Plan to Resist Election Day Misinformation (WIRED)

I'm in danger of sounding old, and even worse, old-fashioned, but everything isn't about entertainment. Someone or something has to be the keeper of the flame.

Being a stickler for accuracy is a drag. It requires making enemies and pushing aside people or institutions who don’t act in good faith.

Noam Cohen, Wikipedia's Plan to Resist Election Day Misinformation (WIRED)

Fighting health disinformation on Wikipedia

This is great to see:

As part of efforts to stop the spread of false information about the coronavirus pandemic, Wikipedia and the World Health Organization announced a collaboration on Thursday: The health agency will grant the online encyclopedia free use of its published information, graphics and videos.

Donald G. McNeil Jr., Wikipedia and W.H.O. Join to Combat Covid Misinformation (The New York Times)

Compared to Twitter's dismal efforts at fighting disinformation, the collaboration is welcome news.

The first W.H.O. items used under the agreement are its “Mythbusters” infographics, which debunk more than two dozen false notions about Covid-19. Future additions could include, for example, treatment guidelines for doctors, said Ryan Merkley, chief of staff at the Wikimedia Foundation, which produces Wikipedia.

Donald G. McNeil Jr., Wikipedia and W.H.O. Join to Combat Covid Misinformation (The New York Times)

More proof that the for-profit private sector is in no way more 'innovative' or effective than non-profits, NGOs, and government agencies.

Saturday soundings

Black Lives Matter. The money from this month's kind supporters of Thought Shrapnel has gone directly to the 70+ community bail funds, mutual aid funds, and racial justice organizers listed here.

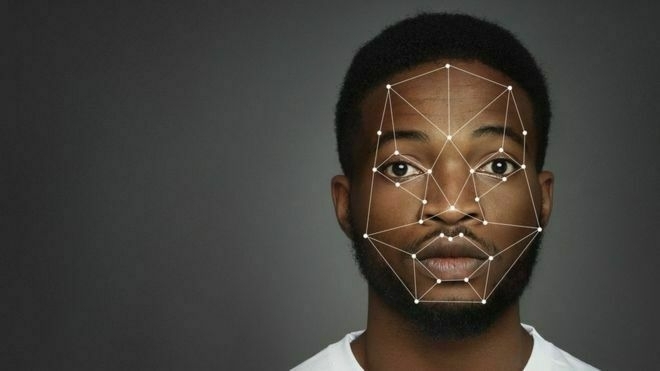

IBM abandons 'biased' facial recognition tech

A 2019 study conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that none of the facial recognition tools from Microsoft, Amazon and IBM were 100% accurate when it came to recognising men and women with dark skin.

And a study from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology suggested facial recognition algorithms were far less accurate at identifying African-American and Asian faces compared with Caucasian ones.

Amazon, whose Rekognition software is used by police departments in the US, is one of the biggest players in the field, but there are also a host of smaller players such as Facewatch, which operates in the UK. Clearview AI, which has been told to stop using images from Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, also sells its software to US police forces.

Maria Axente, AI ethics expert at consultancy firm PwC, said facial recognition had demonstrated "significant ethical risks, mainly in enhancing existing bias and discrimination".

BBC News

Like many newer technologies, facial recognition is already a battleground for people of colour. This is a welcome, if potential cynical move, by IBM who let's not forget literally provided technology to the Nazis.

How Wikipedia Became a Battleground for Racial Justice

If there is one reason to be optimistic about Wikipedia’s coverage of racial justice, it’s this: The project is by nature open-ended and, well, editable. The spike in volunteer Wikipedia contributions stemming from the George Floyd protests is certainly not neutral, at least to the extent that word means being passive in this moment. Still, Koerner cautioned that any long-term change of focus to knowledge equity was unlikely to be easy for the Wikipedia editing community. “I hope that instead of struggling against it they instead lean into their discomfort,” she said. “When we’re uncomfortable, change happens.”

Stephen Harrison (Slate)

This is a fascinating glimpse into Wikipedia and how the commitment to 'neutrality' affects coverage of different types of people and event feeds.

Deeds, not words

Recent events have revealed, again, that the systems we inhabit and use as educators are perfectly designed to get the results they get. The stated desire is there to change the systems we use. Let’s be able to look back to this point in two years and say that we have made a genuine difference.

Nick Dennis

Some great questions here from Nick, some of which are specific to education, whereas others are applicable everywhere.

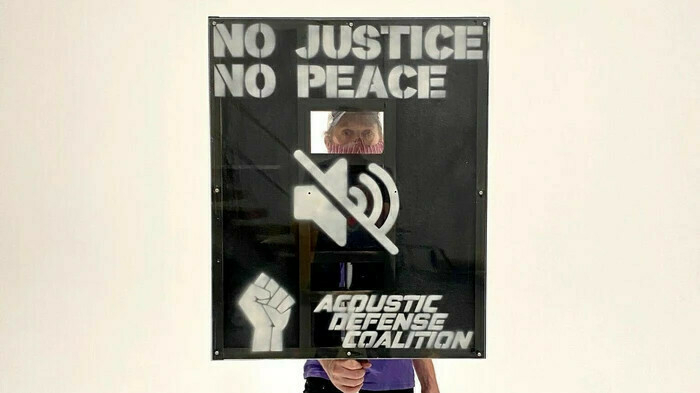

Audio Engineers Built a Shield to Deflect Police Sound Cannons

Since the protests began, demonstrators in multiple cities have reported spotting LRADs, or Long-Range Acoustic Devices, sonic weapons that blast sound waves at crowds over large distances and can cause permanent hearing loss. In response, two audio engineers from New York City have designed and built a shield which they say can block and even partially reflect these harmful sonic blasts back at the police.

Janus Rose (Vice)

For those not familiar with the increasing militarisation of police in the US, this is an interesting read.

CMA to look into Facebook's purchase of gif search engine

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is inviting comments about Facebook’s purchase of a company that currently provides gif search across many of the social network’s competitors, including Twitter and the messaging service Signal.

[...]

[F]or Facebook, the more compelling reason for the purchase may be the data that Giphy has about communication across the web. Since many services that integrate with the platform not only use it to find gifs, but also leave the original clip hosted on Giphy’s servers, the company receives information such as when a message is sent and received, the IP address of both parties, and details about the platforms they are using.

Alex Hern (The Guardian)

In my 2012 TEDx Talk I discussed the memetic power of gifs. Others might find this news surprising, but I don't think I would have been surprised even back then that it would be such a hot topic in 2020.

Also by the Hern this week is an article on Twitter's experiments around getting people to actually read things before they tweet/retweet them. What times we live in.

Human cycles: History as science

To Peter Turchin, who studies population dynamics at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, the appearance of three peaks of political instability at roughly 50-year intervals is not a coincidence. For the past 15 years, Turchin has been taking the mathematical techniques that once allowed him to track predator–prey cycles in forest ecosystems, and applying them to human history. He has analysed historical records on economic activity, demographic trends and outbursts of violence in the United States, and has come to the conclusion that a new wave of internal strife is already on its way1. The peak should occur in about 2020, he says, and will probably be at least as high as the one in around 1970. “I hope it won't be as bad as 1870,” he adds.

Laura Spinney (Nature)

I'm not sure about this at all, because if you go looking for examples of something to fit your theory, you'll find it. Especially when your theory is as generic as this one. It seems like a kind of reverse fortune-telling?

Universal Basic Everything

Much of our economies in the west have been built on the idea of unique ideas, or inventions, which are then protected and monetised. It’s a centuries old way of looking at ideas, but today we also recognise that this method of creating and growing markets around IP protected products has created an unsustainable use of the world’s natural resources and generated too much carbon emission and waste.

Open source and creative commons moves us significantly in the right direction. From open sharing of ideas we can start to think of ideas, services, systems, products and activities which might be essential or basic for sustaining life within the ecological ceiling, whilst also re-inforcing social foundations.

TessyBritton

I'm proud to be part of a co-op that focuses on openness of all forms. This article is a great introduction to anyone who wants a new way of looking at our post-COVID future.

World faces worst food crisis for at least 50 years, UN warns

Lockdowns are slowing harvests, while millions of seasonal labourers are unable to work. Food waste has reached damaging levels, with farmers forced to dump perishable produce as the result of supply chain problems, and in the meat industry plants have been forced to close in some countries.

Even before the lockdowns, the global food system was failing in many areas, according to the UN. The report pointed to conflict, natural disasters, the climate crisis, and the arrival of pests and plant and animal plagues as existing problems. East Africa, for instance, is facing the worst swarms of locusts for decades, while heavy rain is hampering relief efforts.

The additional impact of the coronavirus crisis and lockdowns, and the resulting recession, would compound the damage and tip millions into dire hunger, experts warned.

Fiona Harvey (The Guardian)

The knock-on effects of COVID-19 are going to be with us for a long time yet. And these second-order effects will themselves have effects which, with climate change also being in the mix, could lead to mass migrations and conflict by 2025.

Mice on Acid

What exactly a mouse sees when she’s tripping on DOI—whether the plexiglass walls of her cage begin to melt, or whether the wood chips begin to crawl around like caterpillars—is tied up in the private mysteries of what it’s like to be a mouse. We can’t ask her directly, and, even if we did, her answer probably wouldn’t be of much help.

Cody Kommers (Nautilus)

The bit about 'ego disillusion' in this article, which is ostensibly about how to get legal hallucinogens to market, is really interesting.

Header image by Dmitry Demidov

Microcast #081 - Anarchy, Federation, and the IndieWeb

Happy New Year! It's good to be back.

This week's microcast answers a question from John Johnston about federation and the IndieWeb. I also discuss anarchism and left-libertarianism, for good measure.

Show notes

It’s not a revolution if nobody loses

Thanks to Clay Shirky for today's title. It's true, isn't it? You can't claim something to be a true revolution unless someone, some organisation, or some group of people loses.

I'm happy to say that it's the turn of some older white men to be losing right now, and particularly delighted that those who have spent decades abusing and repressing people are getting their comeuppance.

Enough has been written about Epstein and the fallout from it. You can read about comments made by Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation, in this Washington Post article. I've only met RMS (as he's known) in person once, at the Indie Tech Summit five years ago, but it wasn't a great experience. While I'm willing to cut visionary people some slack, he mostly acted like a jerk.

RMS is a revered figure in Free Software circles and it's actually quite difficult not to agree with his stance on many political and technological matters. That being said, he deserves everything he gets though for the comments he made about child abuse, for the way he's treated women for the past few decades, and his dictator-like approach to software projects.

In an article for WIRED entitled Richard Stallman’s Exit Heralds a New Era in Tech, Noam Cohen writes that we're entering a new age. I certainly hope so.

This is a lesson we are fast learning about freedom as it promoted by the tech world. It is not about ensuring that everyone can express their views and feelings. Freedom, in this telling, is about exclusion. The freedom to drive others away. And, until recently, freedom from consequences.

After 40 years of excluding those who didn’t serve his purposes, however, Stallman finds himself excluded by his peers. Freedom.

Maybe freedom, defined in this crude, top-down way, isn’t the be-all, end-all. Creating a vibrant inclusive community, it turns out, is as important to a software project as a coding breakthrough. Or, to put it in more familiar terms—driving away women, investing your hopes in a single, unassailable leader is a critical bug. The best patch will be to start a movement that is respectful, inclusive, and democratic.

Noam Cohen

One of the things that the next leaders of the Free Software Movement will have to address is how to take practical steps to guarantee our basic freedoms in a world where Big Tech provides surveillance to ever-more-powerful governments.

Cory Doctorow is an obvious person to look to in this regard. He has a history of understanding what's going on and writing about it in ways that people understand. In an article for The Globe and Mail, Doctorow notes that a decline in trust of political systems and experts more generally isn't because people are more gullible:

40 years of rising inequality and industry consolidation have turned our truth-seeking exercises into auctions, in which lawmakers, regulators and administrators are beholden to a small cohort of increasingly wealthy people who hold their financial and career futures in their hands.

[...]

To be in a world where the truth is up for auction is to be set adrift from rationality. No one is qualified to assess all the intensely technical truths required for survival: even if you can master media literacy and sort reputable scientific journals from junk pay-for-play ones; even if you can acquire the statistical literacy to evaluate studies for rigour; even if you can acquire the expertise to evaluate claims about the safety of opioids, you can’t do it all over again for your city’s building code, the aviation-safety standards governing your next flight, the food-safety standards governing the dinner you just ordered.

Cory Doctorow

What's this got to do with technology, and in particular Free Software?

Big Tech is part of this problem... because they have monopolies, thanks to decades of buying nascent competitors and merging with their largest competitors, of cornering vertical markets and crushing rivals who won't sell. Big Tech means that one company is in charge of the social lives of 2.3 billion people; it means another company controls the way we answer every question it occurs to us to ask. It means that companies can assert the right to control which software your devices can run, who can fix them, and when they must be sent to a landfill.

These companies, with their tax evasion, labour abuses, cavalier attitudes toward our privacy and their completely ordinary human frailty and self-deception, are unfit to rule our lives. But no one is fit to be our ruler. We deserve technological self-determination, not a corporatized internet made up of five giant services each filled with screenshots from the other four.

Cory Doctorow

Doctorow suggests breaking up these companies to end their de facto monopolies and level the playing field.

The problem of tech monopolies is something that Stowe Boyd explored in a recent article entitled Are Platforms Commons? Citing previous precedents around railroads, Boyd has many questions, including whether successful platforms be bound with the legal principles of 'common carriers', and finishes with this:

However, just one more question for today: what if ecosystems were constructed so that they were governed by the participants, rather by the hypercapitalist strivings of the platform owners — such as Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook — or the heavy-handed regulators? Is there a middle ground where the needs of the end user and those building, marketing, and shipping products and services can be balanced, and a fair share of the profits are distributed not just through common carrier laws but by the shared economics of a commons, and where the platform orchestrator gets a fair share, as well? We may need to shift our thinking from common carrier to commons carrier, in the near future.

Stowe Boyd

The trouble is, simply establishing a commons doesn't solve all of the problems. In fact, what tends to happen next is well known:

The tragedy of the commons is a situation in a shared-resource system where individual users, acting independently according to their own self-interest, behave contrary to the common good of all users, by depleting or spoiling that resource through their collective action.

Wikipedia

An article in The Economist outlines the usual remedies to the 'tragedy of the commons': either governmental regulation (e.g. airspace), or property rights (e.g. land). However, the article cites the work of Elinor Ostrom, a Nobel prizewinning economist, showing that another way is possible:

An exclusive focus on states and markets as ways to control the use of commons neglects a varied menagerie of institutions throughout history. The information age provides modern examples, for example Wikipedia, a free, user-edited encyclopedia. The digital age would not have dawned without the private rewards that flowed to successful entrepreneurs. But vast swathes of the web that might function well as commons have been left in the hands of rich, relatively unaccountable tech firms.

[...]

A world rich in healthy commons would of necessity be one full of distributed, overlapping institutions of community governance. Cultivating these would be less politically rewarding than privatisation, which allows governments to trade responsibility for cash. But empowering commoners could mend rents in the civic fabric and alleviate frustration with out-of-touch elites.

The Economist

I count myself as someone on the left of politics, if that's how we're measuring things today. However, I don't think we need representation at any higher level than is strictly necessary.

In a time when technology allows you, to a great extent, to represent yourself, perhaps we need ways of demonstrating how complex and multi-faceted some issues are? Perhaps we need to try 'liquid democracy':

Liquid democracy lies between direct and representative democracy. In direct democracy, participants must vote personally on all issues, while in representative democracy participants vote for representatives once in certain election cycles. Meanwhile, liquid democracy does not depend on representatives but rather on a weighted and transitory delegation of votes. Liquid democracy through elections can empower individuals to become sole interpreters of the interests of the nation. It allows for citizens to vote directly on policy issues, delegate their votes on one or multiple policy areas to delegates of their choosing, delegate votes to one or more people, delegated to them as a weighted voter, or get rid of their votes' delegations whenever they please.

WIkipedia

I think, given the state that politics is in right now, it's well worth a try. The problem, of course, is that the losers would be the political elites, the current incumbents. But, hey, it's not a revolution if nobody loses, right?

All is petty, inconstant, and perishable

So said Marcus Aurelius. Today's short article is about what happens after you die. We're all aware of the importance of making a will, particularly if you have dependants. But that's primarily for your analogue, offline life. What about your digital life?

In a recent TechCrunch article, Jon Evans writes:

I really wish I hadn’t had cause to write this piece, but it recently came to my attention, in an especially unfortunate way, that death in the modern era can have a complex and difficult technical aftermath. You should make a will, of course. Of course you should make a will. But many wills only dictate the disposal of your assets. What will happen to the other digital aspects of your life, when you’re gone?

Jon Evans

The article points to a template for a Digital Estate Planning Document which you can use to list all of the places that you're active. Interestingly, the suggestion is to have a 'digital executor', which makes sense as the more technical you are the more likely that other members of your family might not be able to follow your instructions.

Interestingly, the Wikipedia article on digital wills has some very specific advice of which the above-mentioned document is only a part:

I hadn't really thought about this, but the chances of identity theft after someone has died are as great, if not greater, as when they were alive:

An article by Magder in the newspaper The Gazette provides a reminder that identity theft can potentially continue to be a problem even after death if their information is released to the wrong people. This is why online networks and digital executors require proof of a death certificate from a family member of the deceased person in order to acquire access to accounts. There are instances when access may still be denied, because of the prevalence of false death certificates.

Wikipedia

Zooming out a bit, and thinking about this from my own perspective, it's a good idea to insist on good security practices for your nearest and dearest. Ensure they know how to use password managers and use two-factor authentication on their accounts. If they do this for themselves, they'll understand how to do it with your accounts when you're gone.

One thing it's made think about is the length of time for which I renew domain names. I tend to just renew mine (I have quite a few) on a yearly basis. But what if the worst happened? Those payment details would be declined, and my sites would be offline in a year or less.

All of this makes me think that the important thing here is to keep things as simple as possible. As I've discussed in another article, the way people remember us after we're gone is kind of important.

Most of us could, I think, divide our online life into three buckets:

So if, for example, I died tomorrow, the domain renewal for Thought Shrapnel lapsed next year, and a scammer took it over, that would be terrible. It's part of the reason why I still renew domains I don't use. So this would go in the 'really important to my legacy' bucket.

On the other hand, my experiments with various tools and platforms I'm less bothered about. They would probably go in the 'not important' bucket.

Then there's that awkward middle space. Things like the site for my doctoral thesis when the 'official' copy is in the Durham University e-Theses repository.

Ultimately, it's a conversation to have with those close to you. For me, it's on my mind after the death of a good friend and so something I should get to before life goes back to some version of normality. After all, figuring out someone else's digital life admin is the last thing people want when they're already dealing with grief.

Neoliberalism in any guise is not the solution but the problem

Today's quotation-as-title is from Nancy Fraser, whose short book The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born in turn gets its title from a quotation from Antonio Gramsci.

It's an excellent book; quick to read, straight to the point, and it helped me to understand some of what is going on at the moment in both US and world politics.

First, let's explain terms, as it is a book that presupposes some knowledge of political philosophy. 'Neoliberalism' isn't an easy term to define, as its meaning has mutated over time, and it's usually used in a derogatory way.

There's a whole history of the term at Wikipedia, but I'll use definitions from Investopedia and The Guardian:

Neoliberalism is a policy model—bridging politics, social studies, and economics—that seeks to transfer control of economic factors to the private sector from the public sector. It tends towards free-market capitalism and away from government spending, regulation, and public ownership.

Investopedia

In short, “neoliberalism” is not simply a name for pro-market policies, or for the compromises with finance capitalism made by failing social democratic parties. It is a name for a premise that, quietly, has come to regulate all we practise and believe: that competition is the only legitimate organising principle for human activity.

Guardian

To me, it's the reason why humans go out of their way to engineer situations where people and organisations are pitted against each other to compete for 'awards', no matter how made-up or paid-for they may be. It's a way of framing society, human interactions, and reducing everything to $$$.

In that vein, the most recent issue of New Philosopher, features an essay by Warwick Smith where he uses the thought experiment of an AI 'paperclip maximiser'. This runs amok and turns the entire universe into paperclips:

I recently heard Daniel Schmachtenberger taking this thought experiment in a very interesting direction by saying that human society is already the paperclip maximiser but instead of making paperclips we're making dollars — which are primarily just zeroes and ones in bank databases. Our collective intelligence system has on overriding purpose: to turn everything into money — trees, labour, water... everything. It is also very good at learning how to learn and is extremely good at eliminating any threats.

Warwick Smith

This attempt to turn everything into money is basically the neoliberal project. What Nancy Fraser does is identify two different strains of neoliberalism, which she explains through the lenses of 'distribution' and 'recognition':

The difference between these two strands of neoliberalism, then, comes in the way that they recognise people. Note that the method of distribution remains the same:

The political universe that Trump upended was highly restrictive. It was built around the opposition between two versions of neoliberalism, distinguished chiefly on an axis of recognition. Granted, one could choose between multiculturalism and ethnonationalism. But one was stuck, either way, with financialization and deindustrialization. With the menu limited to progressive and reactionary neoliberalism, there was no force to oppose the decimation of working-class and middle-class standards of living. Antineoliberal projects were severely marginalized, if not simply excluded from the public sphere.

Nancy Fraser

It's as if the Overton Window of acceptable public political discourse served up a menu of only different flavours of neoliberalism:

Ideologies are oriented within a narrative that spans the past, present, and future. We can argue over visions of what education should look like within a society, for example, because we're interested in how the next generation will turn out.

In Present Shock, Douglas Rushkoff explains that instead of shackling themselves to ideologies, Trump and other populist politicians take advantage of the 24/7 'always on' media landscape to provide a constant knee-jerk presentism:

A presentist mediascape may prevent the construction of false and misleading narratives by elites who mean us no good, but it also tends to leave everyone looking for direction and responding or overresponding to every bump in the road.

Douglas Rushkoff

What we're witnessing is essentially the end of politics as we know it, says Rushkoff:

As a result, what used to be called statecraft devolves into a constant struggle with crisis management. Leaders cannot get on top of issues, much less ahead of them, as they instead seek merely to respond to the emerging chaos in a way that makes them look authoritative.

[...]

If we have no destination toward we are progressing, then the only thing that motivates our movement is to get away from something threatening. We move from problem to problem, avoiding calamity as best we can, our worldview increasingly characterized by a sense of panic.

[...]

Blatant shock is the only surefire strategy for gaining viewers in the now.

Douglas Rushkoff

We might be witnessing the end of progressive neoliberalism, but it's not as if that's being replaced by anything different, anything better.

What, then, can we expect in the near term? Absent a secure hegemony, we face an unstable interregnum and the continuation of the political crisis. In this situation, the words of Gramsci ring true: "The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear."

Nancy Fraser

No matter what the question is, neoliberalism is never the answer. The trouble, I think, is that two-dimensional diagrams of political options are far too simplistic:

For example, as Edurne Scott Loinaz shows, even within the Libertarian Left (the 'lower left') there are many different positions:

The Libertarian Left has perhaps the best to offer in terms of fighting neoliberalism and populists like Trump. The problem is unity, and use of language:

When binary language is used within the lower left it does untold violence to our communities and makes solidarity impossible: if one can switch between binary language to speak truth about capitalists and authoritarians, and switch to dimensional language within the zone of solidarity with fellow lower leftists, it will be easier to nurture solidarity within the lower left.

Edurne Scott Loinaz

For the first time in my life, I'm actually somewhat fearful of what comes next, politically speaking. Are we going to end up with populists entrenching the authoritarian right, going back full circle to reactionary neoliberalism? Or does this current crisis mean that something new can emerge?

Header image by Guillaume Paumier used under a Creative Commons license

Everyone hustles his life along, and is troubled by a longing for the future and weariness of the present

Thanks to Seneca for today's quotation, taken from his still-all-too-relevant On the Shortness of Life. We're constantly being told that we need to 'hustle' to make it in today's society. However, as Dan Lyons points out in a book I'm currently reading called Lab Rats: how Silicon Valley made work miserable for the rest of us, we're actually being 'immiserated' for the benefit of Venture Capitalists.

As anyone who's read Daniel Kahneman's book Thinking, Fast and Slow will know, there are two dominant types of thinking:

The central thesis is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. The book delineates cognitive biases associated with each type of thinking, starting with Kahneman's own research on loss aversion. From framing choices to people's tendency to replace a difficult question with one which is easy to answer, the book highlights several decades of academic research to suggest that people place too much confidence in human judgement.

WIkipedia

Cal Newport, in a book of the same name, calls 'System 2' something else: Deep Work. Seneca, Kahneman, and Newport, are all basically saying the same thing but with different emphasis. We need to allow ourselves time for the slower and deliberative work that makes us uniquely human.

That kind of work doesn't happen when you're being constantly interrupted, nor when you're in an environment that isn't comfortable, nor when you're fearful that your job may not exist next week. A post for the Nuclino blog entitled Slack Is Not Where 'Deep Work' Happens uses a potentially-apocryphal tale to illustrate the point:

On one morning in 1797, the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was composing his famous poem Kubla Khan, which came to him in an opium-induced dream the night before. Upon waking, he set about writing until he was interrupted by an unknown person from Porlock. The interruption caused him to forget the rest of the lines, and Kubla Khan, only 54 lines long, was never completed.

Nuclino blog

What we're actually doing by forcing everyone to use synchronous tools like Slack is a form of journalistic rhythm — but without everyone being synced-up:

If you haven't read Deep Work, never fear, because there's an epic article by Fadeke Adegbuyi for doist entitled The Complete Guide to Deep Work which is particularly useful:

This is an actionable guide based directly on Newport’s strategies in Deep Work. While we fully recommend reading the book in its entirety, this guide distills all of the research and recommendations into a single actionable resource that you can reference again and again as you build your deep work practice. You’ll learn how to integrate deep work into your life in order to execute at a higher level and discover the rewards that come with regularly losing yourself in meaningful work.

Fadeke Adegbuyi

Lots of articles and podcast episodes say they're 'actionable' or provide 'tactics' for success. I have to say this one delivers. I'd still read Newport's book, though.

Interestingly, despite all of the ridiculousness spouted by VC's, people are pretty clear about how they can do their best work. After a Dropbox survey of 500 US-based workers in the knowledge economy, Ben Taylor outlines four 'lessons' they've learned:

I think we need to reclaim workplace culture from the hustlers, shallow thinkers, and those focused on short-term profit. Let's reflect on how things actually work in practice. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb says about being 'antifragile', let's "look for habits and rules that have been around for a long time".

Also check out:

Gamifying Wikipedia for new editors

Hands up who uses Wikipedia? OK, keep your hands up if you edit it too? Ah.

Not only does Wikipedia need our financial donations to keep running, it also needs our time. To encourage people to edit it, the Wikimedia Foundation have created an ‘adventure’ by way of orientation.

It’s split into seven stages:

Source: Wikipedia (via Scott Leslie)

Atlas of Hillforts

This makes me happy.

Back in 2013, archaeologists at Oxford and Edinburgh teamed up to work on the Atlas of Hillforts. Their four-year mission was identify every single hill fort in Britain and Ireland and their key features. This had never been done before, and as Oxford’s Prof. Gary Lock said it would allow archaeologists to “shed new light on why they were created and how they were used”.Although prehistory is 'not my period' as an historian, I'm fascinated by it, and often incorporate looking for a hill fort during my mountain walks.

When the project was under development, Wikimedia UK was supporting a Wikimedian in Residence (WIR) at the British Library, Andrew Gray. He talked to the the people involved in the project and suggested using Wikipedia to share the results of the project. After all they were going to create a free-to-access online database. Perhaps the information could be used to update Wikipedia’s various lists of hillforts?That data is now live. What a resource! The internet, and in particular working openly, is awesome.

Source: Wikipedia UK