- You Should Own Your Favorite Books in Hard Copy (Lifehacker) — "Most importantly, when you keep physical books around, the people who live with you can browse and try them out too."

- How Creative Commons drives collaboration (Vox) "Although traditional copyright protects creators from others redistributing or repurposing their works entirely, it also restricts access, for both viewers and makers."

- Key Facilitation Skills: Distinguishing Weird from Seductive (Grassroots Economic Organizing) — "As a facilitation trainer the past 15 years, I've collected plenty of data about which lessons have been the most challenging for students to digest."

- Why Being Bored Is Good (The Walrus) — "Boredom, especially the species of it that I am going to label “neoliberal,” depends for its force on the workings of an attention economy in which we are mostly willing participants."

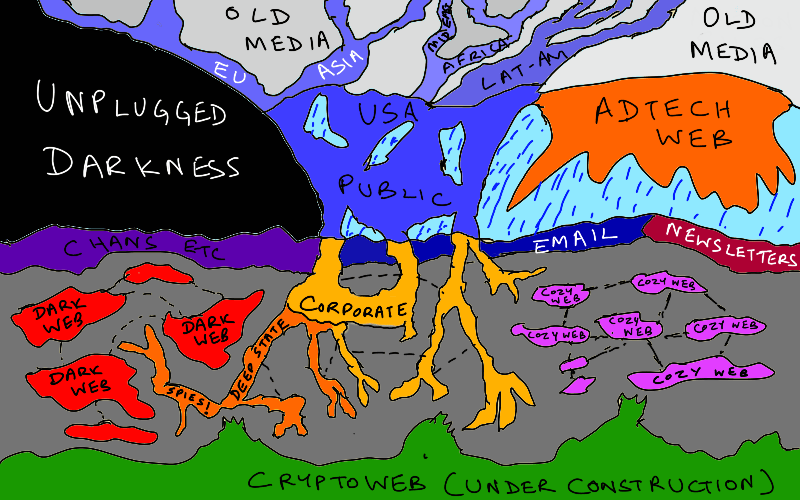

- 5: People having fun on the internet (Near Future Field Notes) — "The internet is still a really great place to explore. But you have to get back into Internet Nature instead of spending all your time in Internet Times Square wondering how everything got so loud and dehumanising."

- The work of a sleepwalking artist offers a glimpse into the fertile slumbering brain (Aeon) "Lee Hadwin has been scribbling in his sleep since early childhood. By the time he was a teen, he was creating elaborate, accomplished drawings and paintings that he had no memory of making – a process that continues today. Even stranger perhaps is that, when he is awake, he has very little interest in or skill for art."

- The Power of One Push-Up (The Atlantic) — "Essentially, these quick metrics serve as surrogates that correlate with all kinds of factors that determine a person’s overall health—which can otherwise be totally impractical, invasive, and expensive to measure directly. If we had to choose a single, simple, universal number to define health, any of these functional metrics might be a better contender than BMI."

- How Wechat censors images in private chats (BoingBoing) — "Wechat maintains a massive index of the MD5 hashes of every image that Chinese censors have prohibited. When a user sends another user an image that matches one of these hashes, it's recognized and blocked at the server before it is transmitted to the recipient, with neither the recipient or the sender being informed that the censorship has taken place."

- It's Never Too Late to Be Successful and Happy (Invincible Career) — "The “race” we are running is a one-person event. The most important comparison is to yourself. Are you doing better than you were last year? Are you a better person than you were yesterday? Are you learning and growing? Are you slowly figuring out what you really want, what makes you happy, and what fulfillment means for you?"

- 'Blitzscaling' Is Choking Innovation—and Wasting Money (WIRED) — "If we learned anything from the dotcom bubble at the turn of the century, it’s that in an environment of abundant capital, money does not necessarily bestow competitive advantage. In fact, spending too much, to soon on unproven business models only heightens the risk that a company's race for global domination can become a race to oblivion."

- ‘Nation as a service’ is the ultimate goal for digitized governments (TNW) — "Right now in Estonia, when you have a baby, you automatically get child benefits. The user doesn’t have to do anything because the government already has all the data to make sure the citizen receives the benefits they’re entitled to."

- The ethics of smart cities (RTE) — "With ethics-washing, a performative ethics is being practised designed to give the impression that an issue is being taken seriously and meaningful action is occurring, when the real ambition is to avoid formal regulation and legal mechanisms."

- Cities as learning platforms (Harold Jarche) — "For the past century we have compartmentalized the life of the citizen. At work, the citizen is an ‘employee’. Outside the office he may be a ‘consumer’. Sometimes she is referred to as a ‘taxpayer’. All of these are constraining labels, ignoring the full spectrum of citizenship.

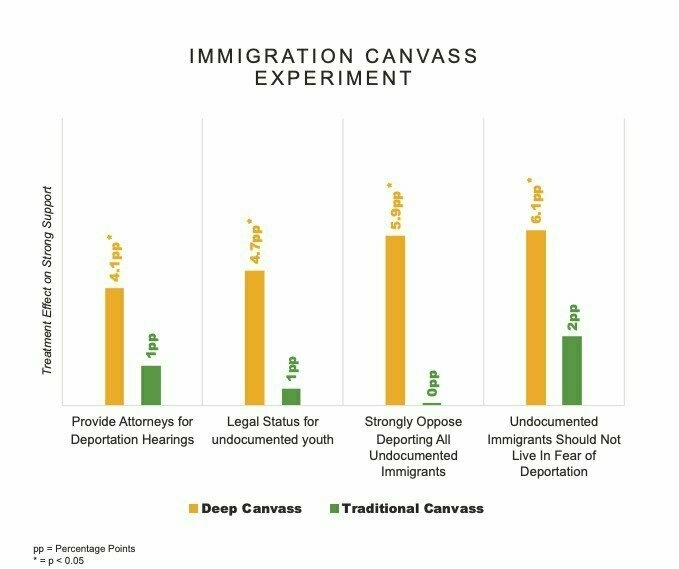

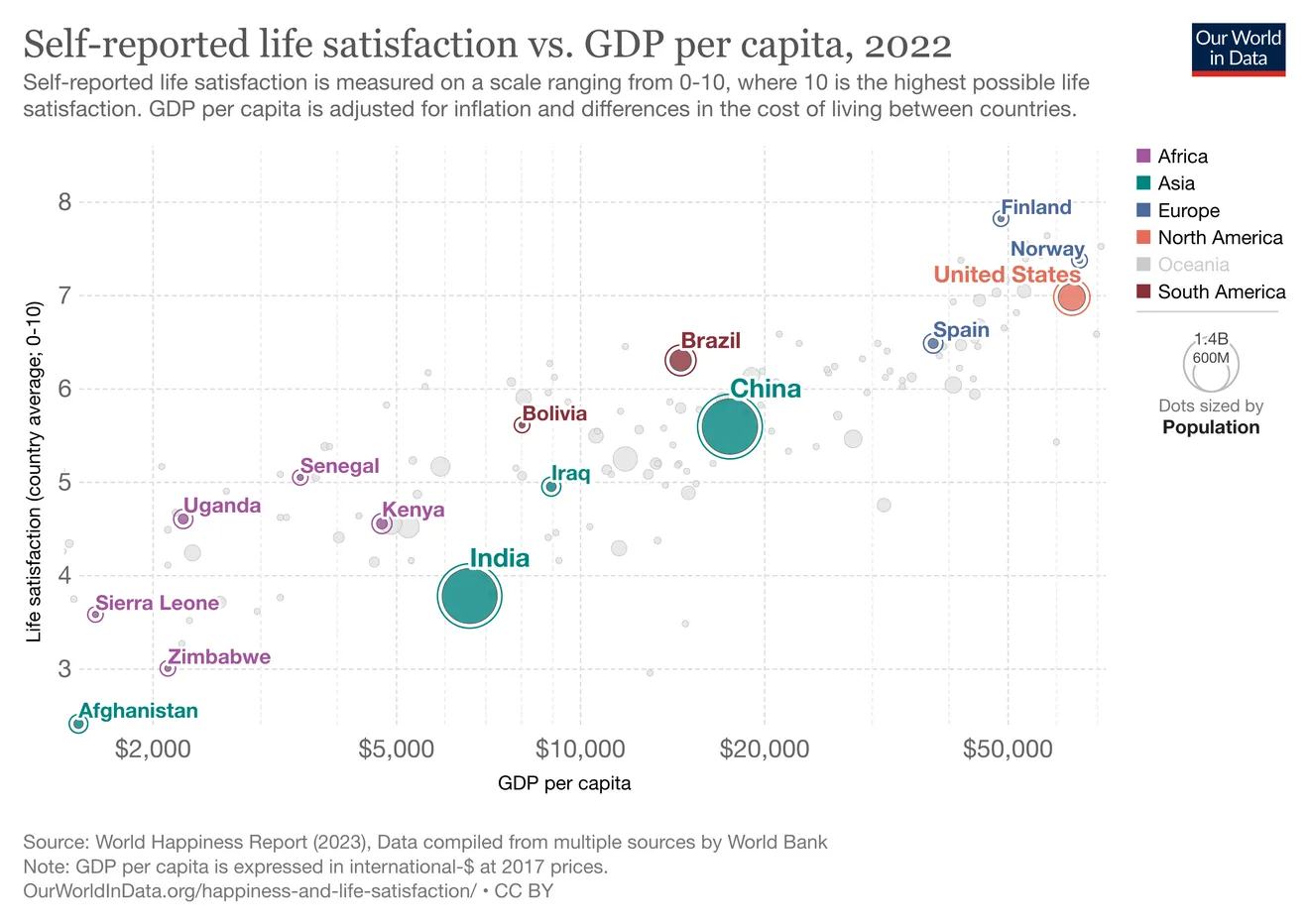

Happiness vs GDP

Making the world a happier, fairer, safer place seems like an idea that most people can get behind. But how do you do it? Although there’s a relationship between average self-reported happiness of a population and increased GDP per capita, there are notable outliers.

So, what to do? Focus on other numbers as well. This article talks about measuring ‘Wellbys’ or ‘well-being-life-adjusted-years’ which involves placing a lot more emphasis on subjective numbers.

The trouble, as anyone who has visited a hospital in England will know, is that self-reported data while useful can be very problematic. For example, when I go into hospital, I know that they will ask me to rate my pain on a scale of 1-10. Being a reasonably stoic kind of person, I used to keep that number low, which not only kept me at the back of the line for being seen, but meant they were less likely to give me painkillers.

Guess what I’ve learned to do? Yep, game the system. People respond to incentives, so although trying to make single numbers go up and to the right might make life easier for those intervening in systems, it doesn’t make those interventions any more effective.

Instead, I’d like to see the focus more on something like the Human Development Index (HDI) which, not only has been around for a while, but is a composite of statistics designed to increase human flourishing.

As we’ve gathered more data on the happiness of different populations, it’s become clear that increasing wealth and health do not always go hand in hand with increasing happiness. By the economists’ objective measures, people in rich countries like the US should be doing great — and yet Americans are only becoming more miserable. And people in some higher-GDP European countries like Portugal and Italy report lower life satisfaction than people in lower-GDP Latin American countries.Source: Make people happier — not just wealthier and healthier | VoxWhat’s going on here? How do we explain the gaps in life satisfaction that objective metrics like GDP don’t explain?

Nowadays, a growing chorus of experts argues that helping people is ultimately about making them happier — not just wealthier or healthier — and the best way to find out how happy people are is to just ask them directly. This camp says we should focus a lot more on subjective well-being: how happy people are, or how satisfied they are with their lives, based on what they say matters most to them — not just based on objective metrics like GDP. Subjective well-being can tell us things that objective metrics can’t.

[…]

Instead, [Michael} Plant [who leads the Happier Lives Institute] argues we should compare how much good different things do in a single “currency” — specifically, how many well-being-adjusted life years, or Wellbys, they produce. Producing one Wellby means increasing life satisfaction by one point (on the 0-10 life satisfaction scale) for one year. It’s a metric that some economists, including those behind the World Happiness Report, are coming to embrace. If we were to evaluate every policy in terms of how many Wellbys it produces, that would allow for direct apples-to-apples comparisons.

“I’m pretty bullish about just using well-being as the [single] measure,” Plant told me.

Using semesters for goal-setting

This article suggests using the academic calendar as a framework for setting and achieving personal goals, breaking life into “semesters” to focus on mini-goals that contribute to larger ambitions. It argues that this approach can aid in time management, motivation, and skill development, offering a structured yet flexible way to make meaningful progress in various aspects of life.

As someone who spent a long time in formal education, was a teacher, and spent time working in Higher Education, it’s difficult to get out of the habit of the academic year and breaking your work into ‘terms’. Perhaps I should be leaning into it?

While it’s important to set goals, the roadmap for how to attain them can be murky. Instead of embarking without a plan toward broad ambitions, there’s value in incremental objectives in service of a larger aim. Take a page from the educational system and divide the future into “semesters” — traditionally 15 to 17 weeks long at American colleges — in which to implement minigoals to help get you where you want to go. Use the traditional academic year as a guide to help you stay on track, says Rachel Wu, an associate professor of psychology at the University of California Riverside. Many community classes and educational opportunities are offered roughly on a quarter or semester basis. “At the very least, it will help people, maybe, feel young again. I think that’s a huge benefit,” Wu says. “They can think back to that point in their life when they had that kind of organization and that might be something that works for them.” (You don’t need to follow a traditional academic structure by any means, but having a firm start and end date within a few months’ span in which to focus on certain skills or activities can help keep you motivated.)Source: Semesters for adults: How the academic school year can help with goal-setting, time management, and motivation | Vox[…]

Modeling your life after academic years allows you to adequately mark your process. It’s difficult to determine improvement with daily or even weekly goals, Fishbach says. But with a quarterly or biannual milestone, you’re more easily able to track your progress; you can more clearly look back on what you’ve learned after a 20-week intro to coding class as opposed to after a few days of instruction. The end of a semester allows for these report cards. “It just helps you feel that you’re growing as a person,” Fishbach says. “You’re not the person you were three months ago.”

[…]

A self-imposed semester system also lends itself to increased motivation due, in part, to the fresh start effect, where people are more driven to pursue goals after a “fresh start” like a new year or semester. (Fully embrace the back-to-school energy and buy some new school supplies, Wu says, “and then learn something.”) With goals that have an endpoint, called an all-or-nothing goal, Fishbach says, motivation increases as you approach the deadline. Having a distinct cutoff to your personal semester can help you stay driven knowing there’s an end in sight.

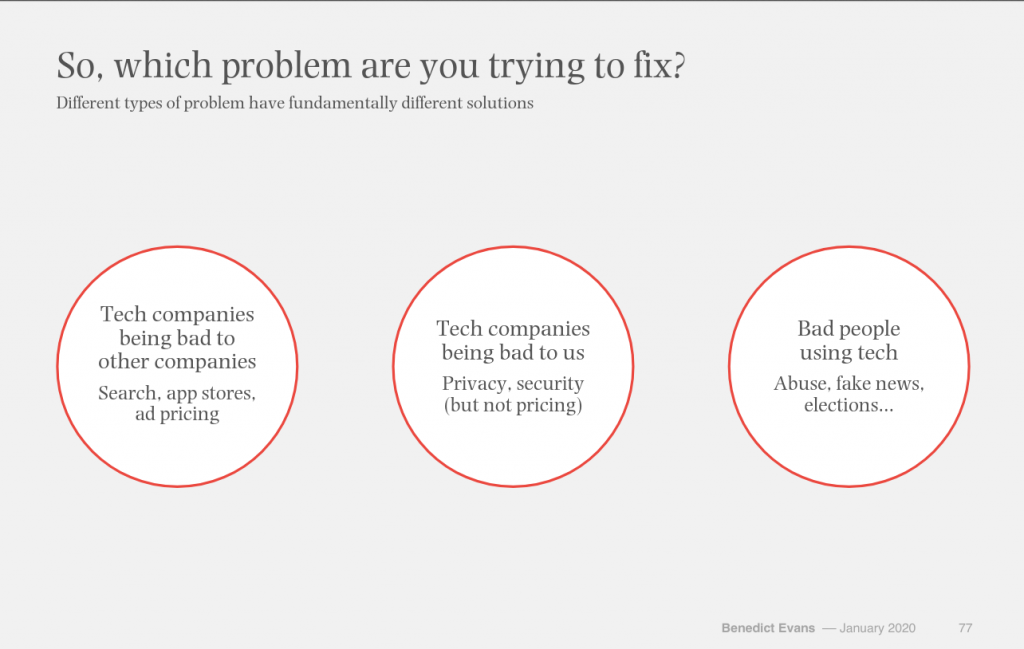

Should we "resist trying to make things better" when it comes to online misinformation?

This is a provocative interview with Alex Stamos, “the former head of security at Facebook who now heads up the Stanford Internet Observatory, which does deep dives into the ways people abuse the internet”. His argument is that social media companies (like Twitter) sometimes try to hard to make the world better, which he thinks should be “resisted”.

I’m not sure what to make of this. On the one hand, I think we absolutely do need to be worried about misinformation. On the other, he does have a very good point about people being complicit in their own radicalisation. It’s complicated.

I think what has happened is there was a massive overestimation of the capability of mis- and disinformation to change people’s minds — of its actual persuasive power. That doesn’t mean it’s not a problem, but we have to reframe how we look at it — as less of something that is done to us and more of a supply and demand problem. We live in a world where people can choose to seal themselves into an information environment that reinforces their preconceived notions, that reinforces the things they want to believe about themselves and about others. And in doing so, they can participate in their own radicalization. They can participate in fooling themselves, but that is not something that’s necessarily being done to them.Source: Are we too worried about misinformation? | Vox[…]

The fundamental problem is that there’s a fundamental disagreement inside people’s heads — that people are inconsistent on what responsibility they believe information intermediaries should have for making society better. People generally believe that if something is against their side, that the platforms have a huge responsibility. And if something is on their side, [the platforms] should have no responsibility. It’s extremely rare to find people who are consistent in this.

[…]

Any technological innovation, you’re going to have some kind of balancing act. The problem is, our political discussion of these things never takes those balances into effect. If you are super into privacy, then you have to also recognize that when you provide people private communication, that some subset of people will use that in ways that you disagree with, in ways that are illegal in ways, and sometimes in some cases that are extremely harmful. The reality is that we have to have these kinds of trade-offs.

Why large tree-planting initiatives often fail

‘Carbon offsetting’ is just a way of the western middle classes assuaging their climate guilt. We can do better by thinking holistically.

In one recent study in the journal Nature, for example, researchers examined long-term restoration efforts in northern India, a country that has invested huge amounts of money into planting over the last 50 years. The authors found “no evidence” that planting offered substantial climate benefits or supported the livelihoods of local communities.Source: Climate change: How to plant trillions of trees without hurting people and the planet | VoxThe study is among the most comprehensive analyses of restoration projects to date, but it’s just one example in a litany of failed campaigns that call into question the value of big tree-planting initiatives. Often, the allure of bold targets obscures the challenges involved in seeing them through, and the underlying forces that destroy ecosystems in the first place.

Instead of focusing on planting huge numbers of trees, experts told Vox, we should focus on growing trees for the long haul, protecting and restoring ecosystems beyond just forests, and empowering the local communities that are best positioned to care for them.

The album is no longer the unit of musical currency

I’m sitting listening to the new Kings of Convenience album while writing this. As this article points out, listening to albums is an increasingly unlikely thing to in the era of streaming music services.

This isn’t accidental: it’s easy to hop between services when the unit of currency is an ‘album’. But when it’s a regularly-updated playlist that’s only available on a particular platform (e.g. Spotify) that’s a different proposition altogether.

To help listeners find their way in the endless aisles of digital music, streaming providers created playlists — but this new way of listening has created unintended consequences for artists and songwriters. Today, three services make up two-thirds of the streaming economy: Spotify, which has an estimated 32 percent of the market, Apple Music (18 percent), and Amazon Music (14 percent). But Spotify dominates the conversation both because of its market power and its immensely popular playlists. In 2017, 68 percent of all listening on Spotify was from a company or user playlist, according to the company’s 2018 Securities and Exchange Commission filing. Its platform has more than 4 billion playlists, 3,000 of which are owned by Spotify, curated by a mix of algorithms and editors.Source: How streaming made hit songs more important than the pop stars who sing them | VoxIts most prominent playlists have serious cultural power. RapCaviar shapes the sound of hip-hop, and can turn indie rappers into household names. The genre-agnostic, slightly quirky playlist Lorem curates the vibe for Spotify’s Gen Z listeners. In 2020, listeners ages 16 to 40 used playlists as their primary source for discovering new music on the platform, according to the company. So today, a placement atop one of its playlists can make or break a song.

Spotify isn’t shy about the marketing power of its playlists. In its SEC filing, the company wrote as much, crediting Lorde’s breakout global success to her placement on a single playlist: Sean Parker’s Hipster International. But her example may be an outlier. The challenge for most artists is that playlist listeners frequently don’t know who they’re listening to. A song with high completion rates on a playlist might end up on more playlists, accumulating millions of streams for an artist who remains effectively nameless. In the best-case scenario, these streams, which pay very low royalties compared to radio, could help land the song a coveted advertisement, or better yet, pique the attention of Top 40 radio programmers.

Friday federations

These things piqued my interest this week:

Image: Federation Square by Julien used under a Creative Commons license

Form is the possibility of structure

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein with today's quotation-as-title. I'm using it as a way in to discuss some things around city planning, and in particular an article I've been meaning to discuss for what seems like ages.

In an article for The LA Times, Jessica Roy highlights a phenomenon I wish I could take back and show my 12 year-old self:

Thirty years ago, Maxis released “SimCity” for Mac and Amiga. It was succeeded by “SimCity 2000” in 1993, “SimCity 3000” in 1999, “SimCity 4” in 2003, a version for the Nintendo DS in 2007, “SimCity: BuildIt” in 2013 and an app launched in 2014.

Along the way, the games have introduced millions of players to the joys and frustrations of zoning, street grids and infrastructure funding — and influenced a generation of people who plan cities for a living. For many urban and transit planners, architects, government officials and activists, “SimCity” was their first taste of running a city. It was the first time they realized that neighborhoods, towns and cities were things that were planned, and that it was someone's job to decide where streets, schools, bus stops and stores were supposed to go.

Jessica Roy

Some games are just awesome. SimCity is still popular now on touchscreen devices, and my kids play it occasionally. It's interesting to read in the article how different people, now responsible for real cities, played the game, for example Roy quotes the Vice President of Transportation and Housing at the non-profit Silicon Valley Leadership Group

"I was not one of the players who enjoyed Godzilla running through your city and destroying it. I enjoyed making my city run well."

Jason Baker

I, on the other hand, particularly enjoyed booting up 'scenario mode' where you had to rescue a city that had been ravaged by Godzilla, aliens, or a natural disaster.

This isn't an article about nostalgia, though, and if you read the article in more depth you realise that it's an interesting insight into our psychology around governance of cities and nations. For example, going back to an article from 2018 that also references SimCity, Devon Zuegel writes:

The way we live is shaped by our infrastructure — the public spaces, building codes, and utilities that serve a city or region. It can act as the foundation for thriving communities, but it can also establish unhealthy patterns when designed poorly.

[...]

People choose to drive despite its costs because they lack reasonable alternatives. Unfortunately, this isn’t an accident of history. Our transportation system has been overly focused on automobile traffic flow as its metric of success. This single-minded focus has come at the cost of infrastructure that supports alternative ways to travel. Traffic flow should, instead, be one goal out of many. Communities would be far healthier if our infrastructure actively encouraged walking, cycling, and other forms of transportation rather than subsidizing driving and ignoring alternatives.

Devon Zuegel

In other words, the decisions we ask our representatives to make have a material impact in shaping our environment. That, in turn, affects our decisions about how to live and work.

When we don't have data about what people actually do, it's easy for ideology and opinions to get in the way. That's why I'm interested in what Los Angeles is doing with its public transport system. As reported by Adam Rogers in WIRED, the city is using mobile phone data to see how it can 'reboot' its bus system. It turns out that the people running the system had completely the wrong assumptions:

In fact, Metro's whole approach turned out to be skewed to the wrong kinds of trips. “Traditionally we're trying to provide fast service for long-distance trips,” [Anurag Komanduri, a data anlyst] says. That's something the Orange Line and trains are good at. But the cell phone data showed that only 16 percent of trips in LA County were longer than 10 miles. Two-thirds of all travel was less than five miles. Short hops, not long hauls, rule the roads.

Adam Rogers

There's some discussion later in the article about the "baller move" of ripping down some of the freeways to force people to use public transportation. Perhaps that's actually what's required.

In Barcelona, for example, "fiery leftist housing activist" Ada Colau became the city's mayor in 2015. Since then, they've been doing some radical experimentation. David Roberts reports for Vox on what they've done with one area of the city that I've actually seen with my own eyes:

Inside the superblock in the Poblenou neighborhood, in the middle of what used to be an intersection, there’s a small playground, with a set of about a dozen picnic tables next to it, just outside a local cafe. On an early October evening, neighbors sit and sip drinks to the sound of children’s shouts and laughter. The sun is still out, and the warm air smells of wild grasses growing in the fresh plantings nearby.

David Roberts

I can highly recommended watching this five-minute video overview of the benefits of this approach:

So if it work, why aren't we seeing more of this? Perhaps it's because, as Simon Wren-Lewis points out on his blog, most of us are governed by incompetents:

An ideology is a collection of ideas that can form a political imperative that overrides evidence. Indeed most right wing think tanks are designed to turn the ideology of neoliberalism into policy based evidence. It was this ideology that led to austerity, the failed health reforms and the privatisation of the probation service. It also played a role in Brexit, with many of its protagonists dreaming of a UK free from regulations on workers rights and the environment. It is why most of the recent examples of incompetence come from the political right.

Simon Wren-Lewis

A pluralist democracy has checks and balances in part to guard against incompetence by a government or ministers. That is one reason why Trump and the Brexiters so often attack elements of a pluralist democracy. The ultimate check on incompetence should be democracy itself: incompetent politicians are thrown out. But when a large part of the media encourage rather than expose acts of incompetence, and the non-partisan media treat knowledge as just another opinion, that safegurd against persistent incompetence is put in danger.

We seem to have started with SimCity and ended with Trump and Brexit. Sorry about that, but without decent government, we can't hope to improve our communities and environment.

Also check out: