On preparing, issuing, and claiming badges

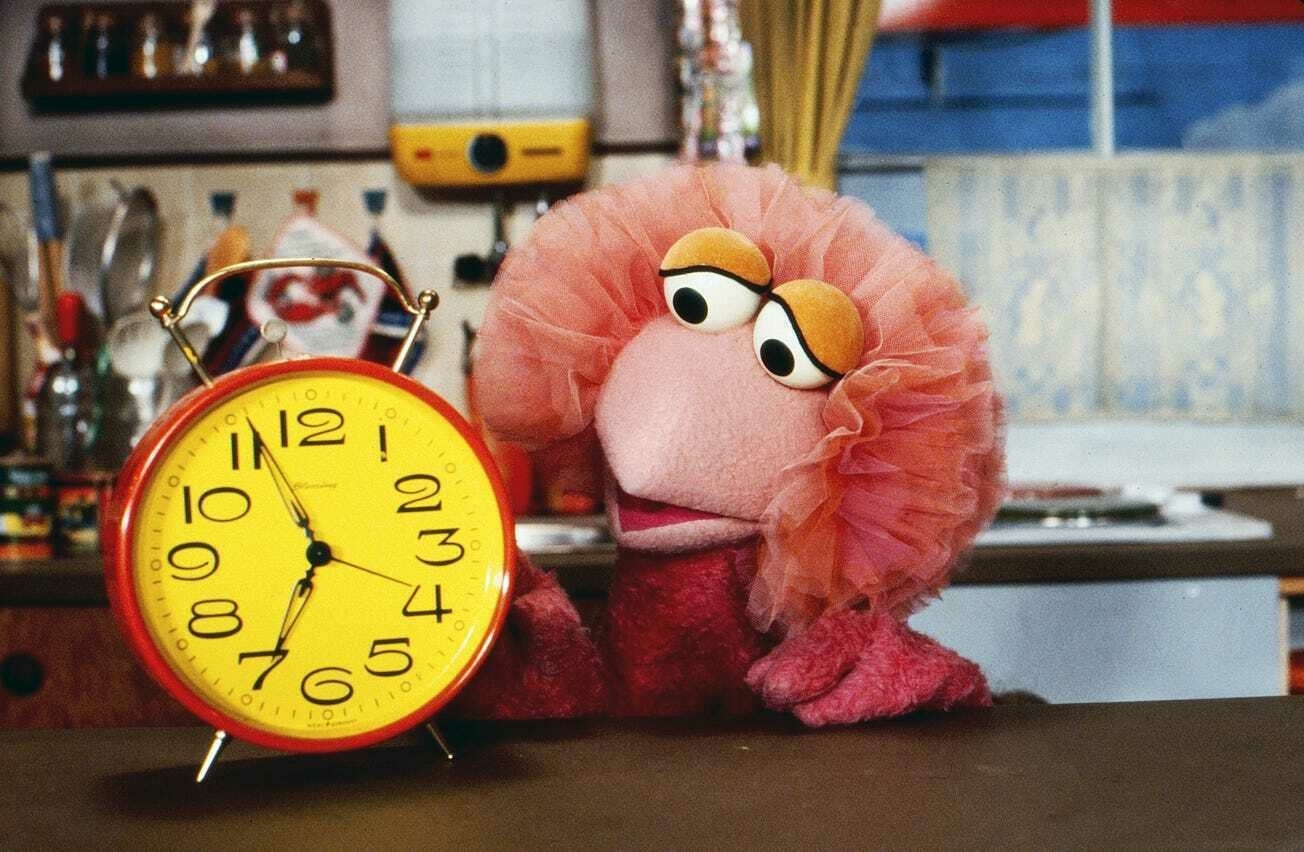

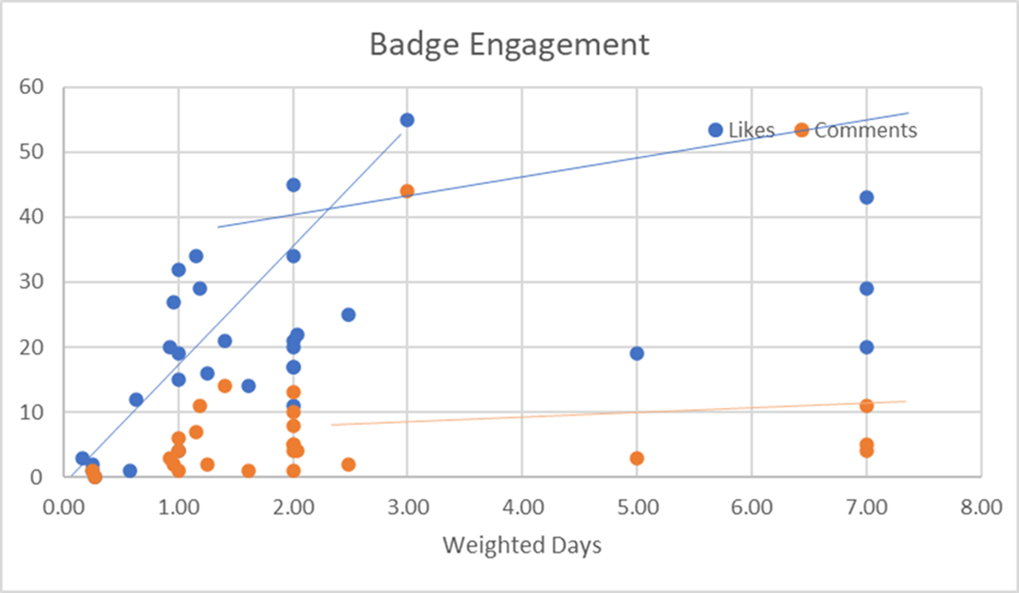

I attended a Navigatr webinar at lunchtime today where they shared this graphic which underscores the importance of encouraging badge earners to share their achievements on social networks.

What I appreciated about the webinar was the way in which the team explained the importance of preparing for and then following up the issue of the badge to ensure that it’s claimed.

Our study of several recently shared digital badges on social media as shown below showed that on average, a posted badge received 500-1k impressions and 25 interactions, of which, 4-5 were actual comments. We found that the number of connections and days since posted lead to increases in the number of interactions. Engagement seemed to plateau around 4-5 days and those with several hundred to 500+ connections were most likely to receive numerous interactions. Location – whether the US or abroad did not seem to matter, suggesting the power of social media is universal when it comes to engagement.Source: Improve Brand Engagement with Digital Badges | BadgeCert

Calendars as data layers

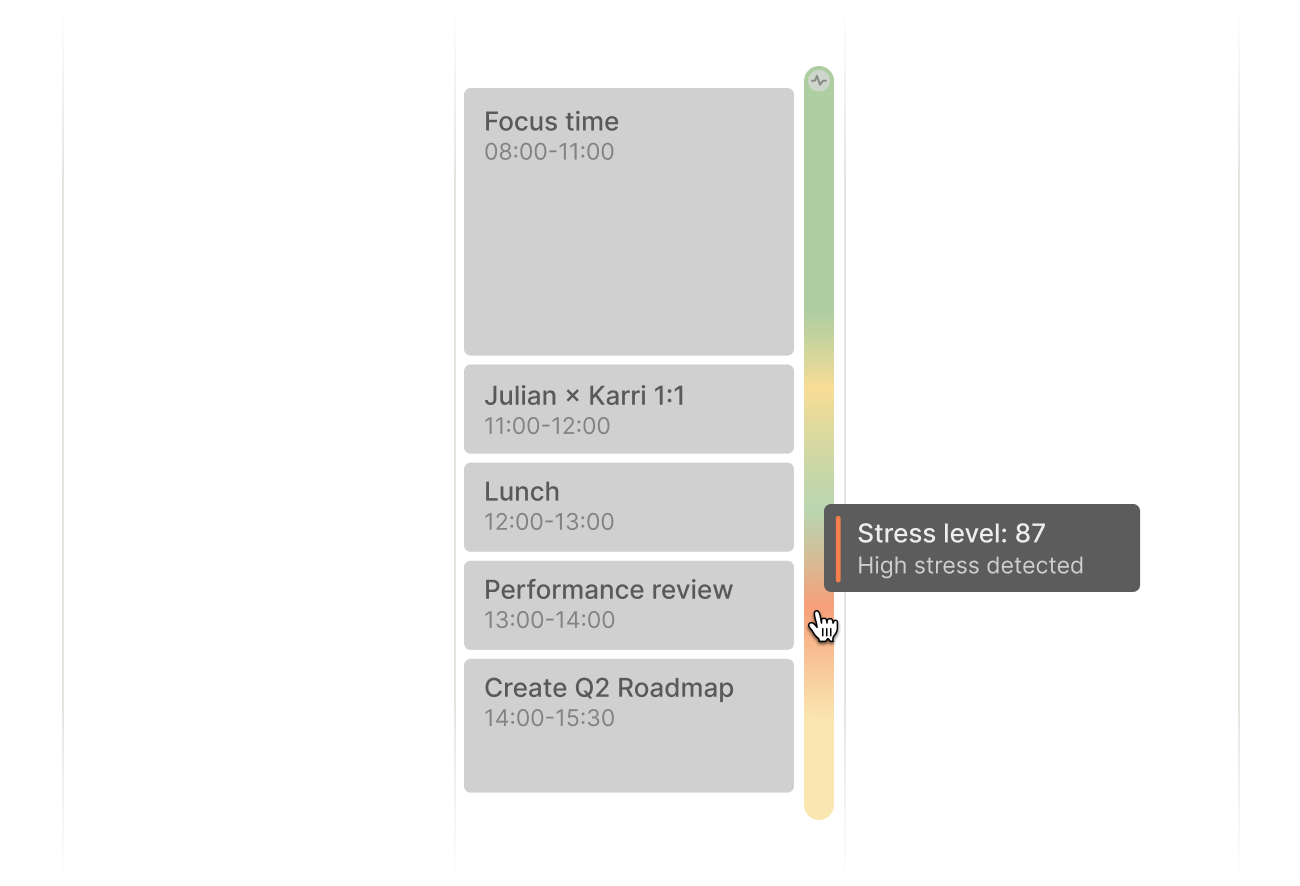

I run my life by Google Calendar, so I found this post about different data layers including both past and future data points really interesting.

As someone who also pays attention to their stress level as reported by a Garmin smartwatch, and as someone who suffers from migraines, this kind of data would be juxtaposition would be super-interesting to me.

Our digital calendars turned out to be just marginally better than their pen and paper predecessors. And since their release, neither Outlook nor Google Calendar have really changed in any meaningful way.Source: Multi-layered calendars | julian.digital[…]

Flights, for example, should be native calendar objects with their own unique attributes to highlight key moments such as boarding times or possible delays.

This gets us to an interesting question: If our calendars were able to support other types of calendar activities, what else could we map onto them?

[…]

Something I never really noticed before is that we only use our calendars to look forward in time, never to reflect on things that happened in the past. That feels like a missed opportunity.

[…]

My biggest gripe with almost all quantified self tools is that they are input-only devices. They are able to collect data, but unable to return any meaningful output. My Garmin watch can tell my current level of stress based on my heart-rate variability, but not what has caused that stress or how I can prevent it in the future. It lacks context.

Once I view the data alongside other events, however, things start to make more sense. Adding workouts or meditation sessions, for example, would give me even more context to understand (and manage) stress.

[…]

Once you start to see the calendar as a time machine that covers more than just future plans, you’ll realize that almost any activity could live in your calendar. As long as it has a time dimension, it can be visualized as a native calendar layer.

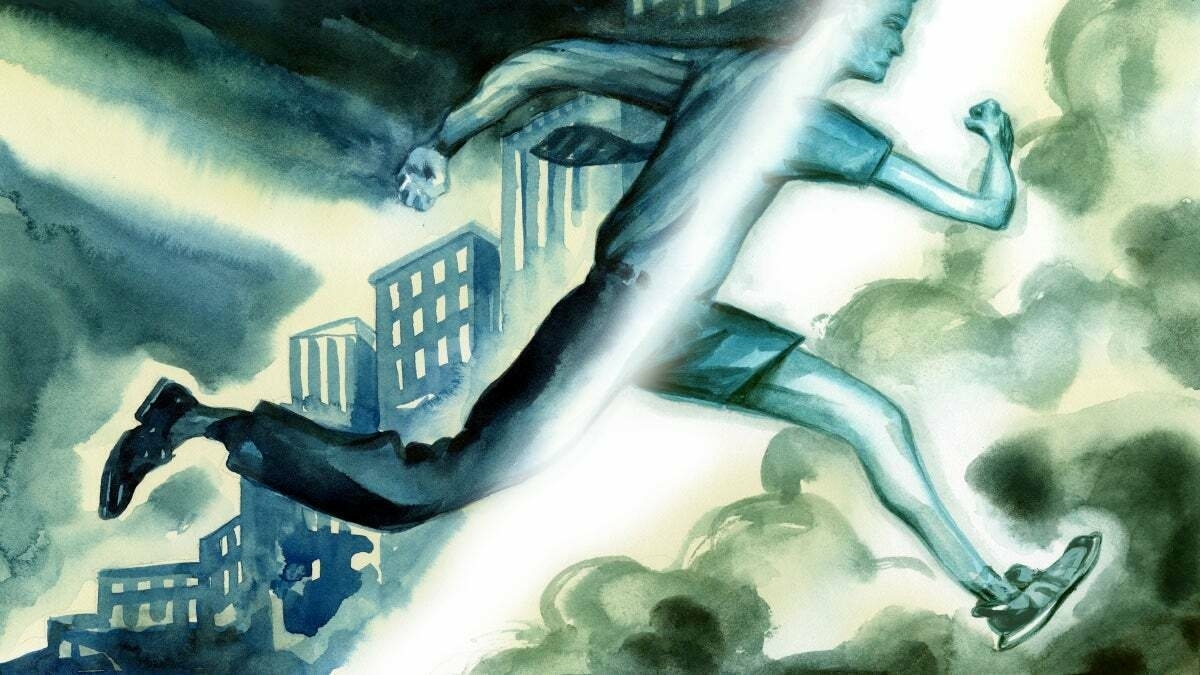

Getting serious

This is a great article by Katherine Boyle that talks about the lack of ‘seriousness’ in the USA, but also considers the wider geopolitical situation. We’re living at a time when world leaders are ever-older, and people between the ages of 18 and 29 just don’t have… that much to do with their time?

The Boomer ascendancy in America and industrialized nations has left us with a global gerontocracy and a languishing generation waiting in the wings. Not only does extended adolescence—what psychologist Erik Erikson first referred to as a “psychosocial moratorium” or the interim years between childhood and adulthood— affect the public life of younger generations, but their private lives as well.Source: It’s Time to Get Serious | The Free Press[…]

In many ways, the emergence of extended adolescence was designed both to coddle the young and to conceal an obvious fact: that the usual leadership turnover across institutions is no longer happening. That the old are quite happy to continue delaying aging and the finality it brings, while the young dither away their prime years with convenient excuses and even better TikTok videos.

[…]

So in 2023, here we are: in a tri-polar geopolitical order led by septuagenarians and octogenarians. Xi Jinping, Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin have little in common, but all three are entering their 70s and 80s, orchestrating the final acts of their political careers and frankly, their lives. That we are beholden to the decisions of leaders whose worldviews were shaped by the wars, famines, and innovations of a bygone world, pre-Internet and before widespread mass education, is in part why our political culture feels so stale. That the gerontocracy is a global phenomenon and not just an American quirk should concern us: younger generations who are native to technological strength, modern science and emerging cultural ailments are still sidelined and pursuing status markers they should have achieved a decade ago.

The week as an human construct

This article in Aeon was published at around the same time as I published a post on my personal blog about time as a human construct. In that post, I talked about the French Republican calendar and the link between it and the weather.

What’s interesting in this article is that the author, David Henkin, a history professor, talks about the success of the week as being because it’s not attached to religious, cultural, or climatological norms.

Weeks serve as powerful mnemonic anchors because they are fundamentally artificial. Unlike days, months and years, all of which track, approximate, mimic or at least allude to some natural process (with hours, minutes and seconds representing neat fractions of those larger units), the week finds its foundation entirely in history. To say ‘today is Tuesday’ is to make a claim about the past rather than about the stars or the tides or the weather. We are asserting that a certain number of days, reckoned by uninterrupted counts of seven, separate today from some earlier moment.Source: How we came to depend on the week despite its artificiality | Aeon[…]

The modern week has superimposed upon the ancient week a rhythm that is fundamentally social, incorporating an awareness of the demands and constraints of other people. Yet the modern week is also somewhat individualised, inasmuch as its rhythms are shaped by all sorts of private decisions we make, especially as consumers. Whereas Sabbath counts and astrological dominions subject everyone to the same schedule, the modern week makes us aware of our relationship to our networks and to the habits of others, while simultaneously highlighting the variety of our networks and the contingency of those habits.

Paying for everything twice

As someone who’s recently started using a budgeting app, and who has a lot of music-making equipment lying around unused, I concur.

One financial lesson they should teach in school is that most of the things we buy have to be paid for twice.Source: Everything Must Be Paid for Twice | RaptitudeThere’s the first price, usually paid in dollars, just to gain possession of the desired thing, whatever it is: a book, a budgeting app, a unicycle, a bundle of kale.

But then, in order to make use of the thing, you must also pay a second price. This is the effort and initiative required to gain its benefits, and it can be much higher than the first price.

A new novel, for example, might require twenty dollars for its first price—and ten hours of dedicated reading time for its second. Only once the second price is being paid do you see any return on the first one. Paying only the first price is about the same as throwing money in the garbage.

Likewise, after buying the budgeting app, you have to set it all up, and learn to use it habitually before it actually improves your financial life. With the unicycle, you have to endure the presumably painful beginner phase before you can cruise down the street. The kale must be de-veined, chopped, steamed, and chewed before it gives you any nourishment.

If you look around your home, you might notice many possessions for which you’ve paid the first price but not the second. Unused memberships, unread books, unplayed games, unknitted yarns.

Introspections on timewasting

What I’ve learned over the years from my own experience is that what one person calls a “waste of time” is the complete opposite for someone else. It also has a temporal/timing element to it, as well, I’d argue.

For example, I spent an inordinate amount of time on Twitter between 2007 and 2012, but this paid off massively in terms of my career. I learned a lot and made really valuable connections in the process. My wife thought it was a waste of my time. These days, it absolutely would be.

In this post, the author reflects on why they “waste time” and look at different reasons as well as various ways they’ve sought to combat it. As someone who’s been through therapy, I’d suggest that there’s always something below the surface that needs a skilled professional to draw out.

That’s what seems missing here.

I spend way too much time on reddit, hacker news, twitter, feedly, coinbase, robinhood, email, etc. I’d like to spend time on things that are more meaningful - chess, digital painting, side projects, reading, video games, exercising, meditating, etc. This has been a problem for years.Source: Scattered Thoughts on Why I Waste My Own Time | Just a blogThis post is only slightly adapted from my personal notes, so excuse the lack of structure; I didn’t want to try to twist this jumble of thoughts into a narrative.

Image: CC BY mysza831

Middle class pursuit of pain through endurance sports is a thing

Oh this is fascinating. Get to your forties and everyone seems to be interested in marathons, triathlons, and putting on lycra to go and cycle somewhere.

This article explains that this is a function not only of access to the required time and money, but is a deep-seated need for those who are doing well out of the capitalist system.

Participating in endurance sports requires two main things: lots of time and money. Time because training, traveling, racing, recovery, and the inevitable hours one spends tinkering with gear accumulate—training just one hour per day, for example, adds up to more than two full weeks over the course of a year. And money because, well, our sports are not cheap: According to the New York Times, the total cost of running a marathon—arguably the least gear-intensive and costly of all endurance sports—can easily be north of $1,600.Source: Why Do Rich People Love Endurance Sports? - Outside Online[…]

There are a handful of obvious reasons the vast majority of endurance athletes are employed, educated, and financially secure. As stated, the ability to train and compete demands that one has time, money, access to facilities, and a safe space to practice, says William Bridel, a professor at the University of Calgary who studies the sociocultural aspects of sport. “The cost of equipment, race entry fees, and travel to events works to exclude lower socioeconomic status individuals,” he says, adding that those in a higher socioeconomic bracket tend to have nine-to-five jobs that provide some freedom to, for example, train before or after work or even at at lunch. “Almost all of the non-elite Ironman athletes who I’ve interviewed for my research had what would be considered white-collar jobs and commented on the flexibility this provided,” says Bridel.

[…]

Even so, there are myriad ways for relatively comfortable middle-to-upper-class individuals to spend their time and money. What is it about the voluntary suffering of endurance sports that attracts them?

This is a question sociologists are just beginning to unpack. One hypothesis is that endurance sports offer something that most modern-day knowledge economy jobs do not: the chance to pursue a clear and measurable goal with a direct line back to the work they have put in. In his book Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work, philosopher Matthew Crawford writes that “despite the proliferation of contrived metrics,” most knowledge economy jobs suffer from “a lack of objective standards.”

[…]

Another reason white-collar workers are flocking to endurance sports has to do with the sheer physicality involved. For a study published in the Journal of Consumer Research this past February, a group of international researchers set out to understand why people with desk jobs are attracted to grueling athletic events. They interviewed 26 Tough Mudder participants and read online forums dedicated to obstacle course racing. What emerged was a resounding theme: the pursuit of pain.

“By flooding the consciousness with gnawing unpleasantness, pain provides a temporary relief from the burdens of self-awareness,” write the researchers. “When leaving marks and wounds, pain helps consumers create the story of a fulfilled life. In a context of decreased physicality, [obstacle course races] play a major role in selling pain to the saturated selves of knowledge workers, who use pain as a way to simultaneously escape reflexivity and craft their life narrative.” The pursuit of pain has become so common among well-to-do endurance athletes that scientific articles have been written about what researchers are calling “white-collar rhabdomyolysis,” referring to a condition in which extreme exercise causes kidney damage.

Time millionaires

Same idea, new name: there’s nothing new about the idea of prioritising the amount of time and agency you have over the amount of money you make.

It’s just that, after the pandemic, more people have realised that chasing money is a fool’s errand. So, whatever you call it, putting your own wellbeing before the treadmill of work and career is always a smart move.

First named by the writer Nilanjana Roy in a 2016 column in the Financial Times, time millionaires measure their worth not in terms of financial capital, but according to the seconds, minutes and hours they claw back from employment for leisure and recreation. “Wealth can bring comfort and security in its wake,” says Roy. “But I wish we were taught to place as high a value on our time as we do on our bank accounts – because how you spend your hours and your days is how you spend your life.”Source: Time millionaires: meet the people pursuing the pleasure of leisure | The GuardianAnd the pandemic has created a new cohort of time millionaires. The UK and the US are currently in the grip of a workforce crisis. One recent survey found that more than 56% of unemployed people were not actively looking for a new job. Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that many people are not returning to their pre-pandemic jobs, or if they are, they are requesting to work from home, clawing back all those hours previously lost to commuting.

Five-hour workdays

I’ve been saying for as long as anyone will listen to me that I can do a maximum of four hours high-quality knowledge work per day. Add on some time for emails and ‘sync’ meetings, and five seems about right.

The difficulty, of course, is the financial side of things. If you’re employed, will your employer pay you the same amount for working fewer hours? (even if productivity increases). And if you’re self-employed, will clients sign-off contracts that stipulate five-hour days?

The eight-hour working day is a relatively new concept, widely accepted to have been cemented by Ford Motor Company a century ago as a means of keeping production going 24 hours a day without putting undue demands on individual members of staff. Ford’s experiment led to an increase in overall productivity; but proponents of five-hour days, including Californian ecommerce business Tower Paddle Boards and German digital consultancy Rheingans, say they experienced a similar phenomenon when they moved to compressed-hour models.Source: The perfect number of hours to work every day? Five | WIREDLike Corcoran, Tower CEO Stephan Aarstol says he was startled by the results when the business adopted a five-hour working day in 2015. Staff worked from 8am to 1pm with no breaks and, because employees became so focused on maximising output in order to have the afternoons to themselves, turnover increased by 50 per cent.

Aren’t you ashamed to reserve for yourself only the remnants of your life and to dedicate to wisdom only that time can’t be directed to business?

Once you remove the specific details from the lives of the ancients, their lives were remarkably like ours. Take today's title, for example, which is a quotation from Seneca. He knew what it was like to be so busy doing 'productive' things to the exclusion of almost everything else.

My good friend Laura Hilliger wears her heart on her sleeve, and is the most no-nonsense person I know. By observing the way she lives and works, I'm learning to set limits and say exactly what I think:

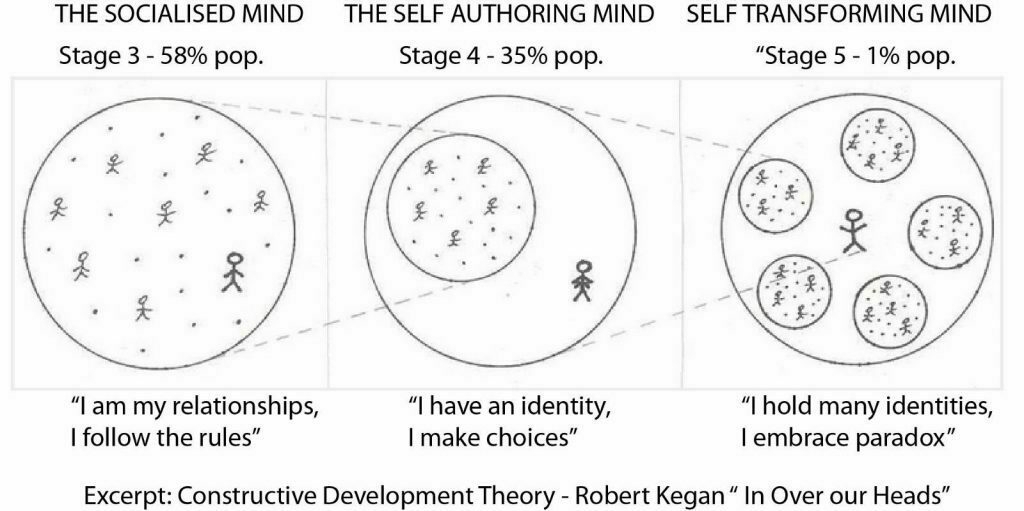

The thing is that western society, implicitly at least, assumes that people are 'fixed' in terms of their personality and likes. But that's just the way that we choose to see ourselves:

I feel that the biggest thing that constrains us is our view of how we think other people see us. That perceived expectation becomes internalised, creating a 'psychic prison' which becomes an extremely limited playground. For better or for worse, we perform the role of how we think other people have come to see us.

One way many people find to avoid responsibility for their life choices is to play the 'busy' card. They're too busy to make good decisions, to look after their mental and physical health, to ensure that they're doing your best work.

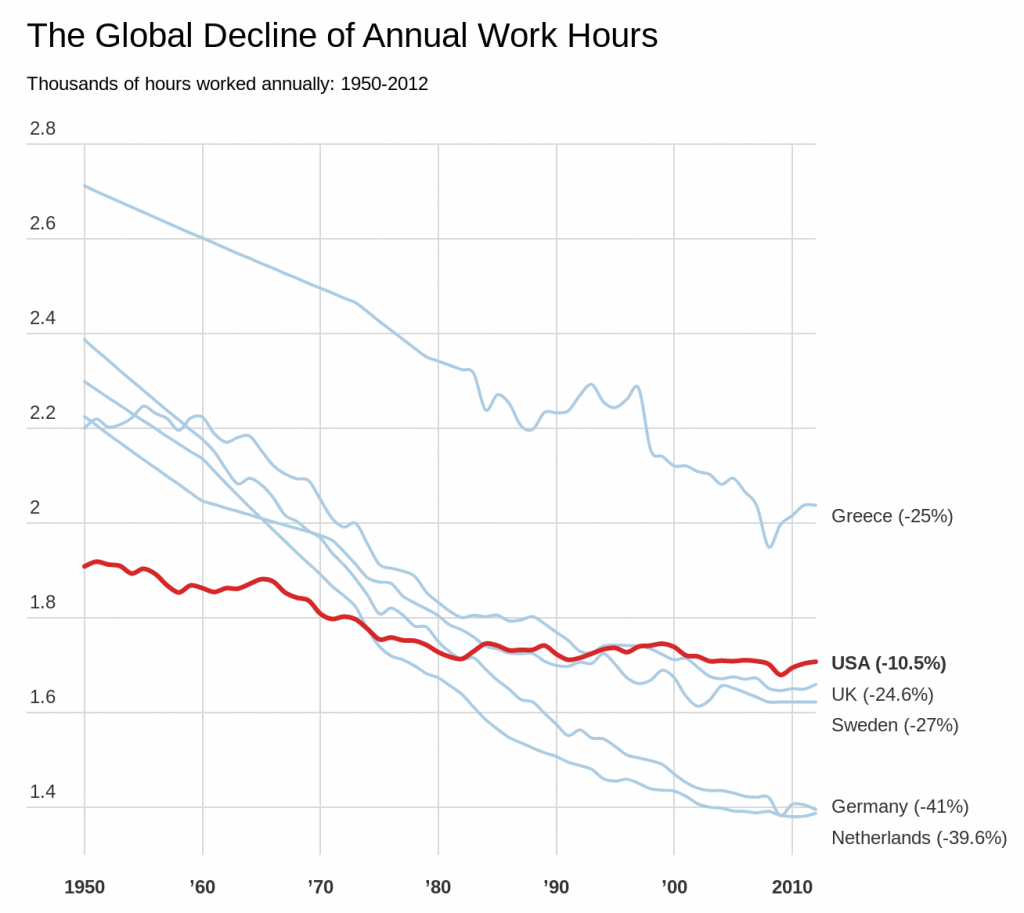

The trouble is, that's simply not true. We've got more free time than our parents and grandparents:

As the above chart demonstrates, it's not true that we actually work more hours. Instead, I think, it's that we're so concerned about how other people see us that we spend time doing things that feel like work but are mostly to do with presentation of self. Hence the amount of time spent on social networks like Instagram trying to create the highlights reel of our lives to show others.

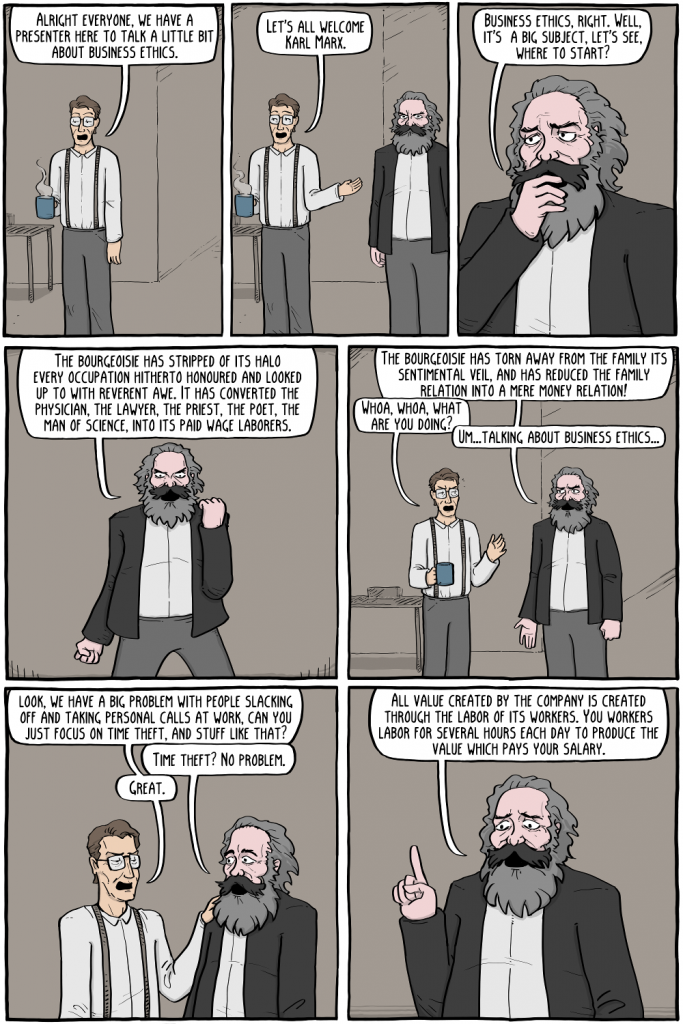

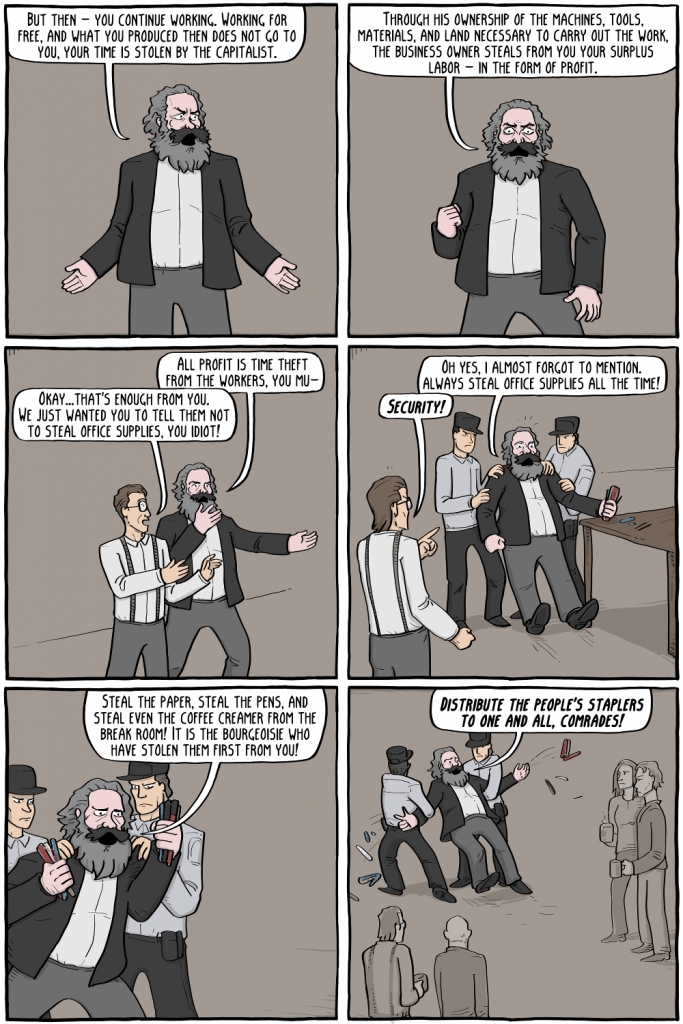

One way of viewing this is that we've collectively internalised capitalism. The logic of the market has become as invisible to us as an ideology as water is to fish. In fact, some people say it's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism!

Of course, it's become something of a cliché in our pseudo-enlightened times to talk of capitalism as the meta-problem behind everything. But that doesn't make it any less true.

Our identity is mediated by the market, by what we produce instead of who we are. I keep coming back to a fantastic episode of Jocelyn K. Glei's Hurry Slowly podcast entitled Who Are You Without The Doing? in which she explains that we should learn to 'sit with ourselves', learning that change comes from within:

You have to completely conquer the feeling that there is something fundamentally wrong with your human nature, and that therefore you need discipline to correct your behavior. As long as you feel the discipline comes from the outside, there is still a feeling that something is lacking in you.

Jocelyn K. Glei

Derek Sivers uses the metaphor of 'doors' to explain where he finds value and wants to spend time doing. Some doors he opens and it helps him grow as a person and fosters positive relationships.

But one door is really no fun to open. I’m horrified at all the shouting, the second I open it. It’s an infinite dark room filled with psychologically tortured people, trying to get attention. Strangers screaming at strangers, starting fights. Businesses set up shop there, showing who’s said and done bad things today, because they make money when people get mad.

Derek Sivers

We keep wringing our hands about people's behaviour online, but it's that way for a reason. Hate is profitable for social networks:

Massive platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube “optimize for engagement,” and make automatic, algorithmic suggestions for every bit of content or action. From “you might also like” to “recommended just for you” to prioritizing things — anything — that will get you to click, comment, or share.

[...]

They know what will catch your attention. They know what will get you “engaged.” They know what will be more likely to lead you deeper into a rabbit hole, and what will make it harder to climb back out. Is it a literal, iron-clad trap? No. But the slippery, spiral path that leads people to the darkest corners of the internet is not an accident.

[...]

Hate is profitable. Conflict is profitable. Schadenfreude and shame are profitable. While we smugly point fingers, tsk-tsk, and think we’re being clever as we strategically dole out likes and shares, we forget that we are all just gruel-fed hamsters running on wheels deep inside giant, hyper-engineered, artificially intelligent, fully gamified, corporate-controlled virtual worlds that we absurdly think belong to us.

Ryan Ozawa

This all comes back to the time equation. Because we feel like we don't have enough time to curate things ourselves, we outsource that to others. That ends up with handing our information environments over to others to manipulate and control. It's curate or be curated.

Nobody cares about how much money you earn. Nobody cares how productive you are. Not really.

Also, without sounding harsh, nobody else cares how productive you are. Of course, productivity is important for important things, and “getting stuff done” or whatever, but it doesn’t define you in any way. What does is things like your sense of humour, where your passions lie, how you comfort a friend who’s upset, and that weird noise you make when the delivery guy calls you to say he’s outside with your food.

Leila Mitwally

The trouble is that we don't want to have this conversation, because it questions our identity, and everything we've been working for over our careers and throughout our lives:

But we don’t want to hear that because accepting this truth means asking a lot of complicated questions about our society, in which work is glorified as the pinnacle of self-expression, and personal earnings are viewed as a measure of merit and esteem.

Instead, we would instead read about buy into the idea that success in our work life is a merely a matter of being more productive. If you just follow the ‘right’ set of algorithms or rules, you too can achieve ‘success’ in your work life, along with fame and recognition and a fat bank account.

Richard Whittall

So, to finish, let me revisit a link I shared recently from Jason Hickel. We can choose to live differently, to recognise the abundance of time and resources we have in the world. To slow down, to take stock, and reject economic growth as in any way a useful indicator of human flourishing:

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can call a halt to the madness – throw a wrench in the juggernaut. By de-enclosing social goods and restoring the commons, we can ensure that people are able to access the things that they need to live a good life without having to generate piles of income in order to do so, and without feeding the never-ending growth machine. “Private riches” may shrink, as Lauderdale pointed out, but public wealth will increase.

Jason Hickel

It doesn't have to be difficult. We can just, as Dan Lyons mentions in his book Lab Rats, decide to work on things that 'close the gap' or 'increase the gap'. What that means to you, in your context, is a different matter.

Audiobooks vs reading

Although I listen to a lot of podcasts (here’s my OPML file) I don’t listen to many audiobooks. That’s partly because I never feel up-to-date with my podcast listening, but also because I often read before going to sleep. It’s much more difficult to find your place again if you drift off while listening than while reading!

This article in TIME magazine (is it still a ‘magazine’?) looks at the research into whether listening to an audiobook is like reading using your eyes. Well, first off, it would seem that there’s no difference in recall of facts given a non-fiction text:

For a 2016 study, Rogowsky put her assumptions to the test. One group in her study listened to sections of Unbroken, a nonfiction book about World War II by Laura Hillenbrand, while a second group read the same parts on an e-reader. She included a third group that both read and listened at the same time. Afterward, everyone took a quiz designed to measure how well they had absorbed the material. “We found no significant differences in comprehension between reading, listening, or reading and listening simultaneously,” Rogowsky says.However, the difficulty here is that there's already an observed discrepancy in recall between dead-tree books and e-books. So perhaps audiobooks are as good as e-books, but both aren't as good as printed matter?

There’s a really interesting point made in the article about how dead-tree books allow for a slight ‘rest’ while you’re reading:

If you’re reading, it’s pretty easy to go back and find the point at which you zoned out. It’s not so easy if you’re listening to a recording, Daniel says. Especially if you’re grappling with a complicated text, the ability to quickly backtrack and re-examine the material may aid learning, and this is likely easier to do while reading than while listening. “Turning the page of a book also gives you a slight break,” he says. This brief pause may create space for your brain to store or savor the information you’re absorbing.This reminds me of an article on Lifehacker a few years ago that quoted a YouTuber who swears by reading a book while also listening to it:

First of all, it combines two senses…so you end up with really good comprehension while being really efficient at the same time. ...Another possibly even more important benefit is…it keeps you going. So you’re not going back and rereading things, you’re not taking all kinds of unnecessary breaks and pauses, your eyes aren’t running around all the time, and you’re not getting distracted every two minutes.Since switching to an open source e-reader, I'm no longer using the Amazon Kindle ecosystem so much these days. If I were, I'd be experimenting with their WhisperSync technology that allows you to either pick up where you left up with one medium — or, indeed, use both at the same time.

Source: TIME / Lifehacker

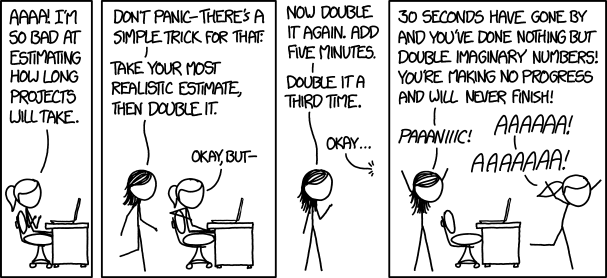

Arbitrary deadlines are the enemy of creativity

People like deadlines because people like accountability. There’s nothing wrong with that, apart from the fact that sometimes it’s impossible to know how long something will take, or cost, or even look like in advance. Creativity, in other words, is at odds with arbitrary deadlines:

We may tease them for their diva-like behaviors when they feel persecuted by a deadline, but we have to admit that “develop an amazing new idea” is not something that slides into your schedule, like pick up lunch or respond to new clients. Nor can systems be tweaked and extra hands hired to help hit a goal that requires innovation, the way they can when mundane busy work is piling up. And yet deadlines are a fact of life for any company that wants to stay competitive.Time is a human construct, not something that's objectively 'out there' in the world. As a result it can be interpreted differently in various situations:

Creative work operates on “event time,” meaning it always requires as much time as needed to organically get the job done. (Think of novel writers or other artists.) Other types of work operate on “clock time,” and are aligned with scheduled events. (A teacher obeys classroom hours and the semester calendar, for instance. An Amazon warehouse manager knows the number of customer orders that can be fulfilled in an hour.)I don't particularly like the phrase 'creative people' in this article, as I believe everyone is (or at least can be) creative. Having said that, I agree with the sentiment:

Creative people need another scarce commodity: mental space. Working in a large team and constantly collaborating as a group doesn’t allow a person the clarity of mind to solve problems with fresh ingenious ideas. “Alone time or working with just one close collaborator seemed to be the key under the low time pressure conditions,” says Amabile.Source: QuartzCreative people, she adds, “have to be protected. They have to be isolated in a way, from all the other stuff that comes up during a work day. They can’t be called into meetings that are unrelated to this serious problem that they’re trying to address.”

Arbitrary deadlines are the enemy of creativity

People like deadlines because people like accountability. There’s nothing wrong with that, apart from the fact that sometimes it’s impossible to know how long something will take, or cost, or even look like in advance. Creativity, in other words, is at odds with arbitrary deadlines:

We may tease them for their diva-like behaviors when they feel persecuted by a deadline, but we have to admit that “develop an amazing new idea” is not something that slides into your schedule, like pick up lunch or respond to new clients. Nor can systems be tweaked and extra hands hired to help hit a goal that requires innovation, the way they can when mundane busy work is piling up. And yet deadlines are a fact of life for any company that wants to stay competitive.Time is a human construct, not something that's objectively 'out there' in the world. As a result it can be interpreted differently in various situations:

Creative work operates on “event time,” meaning it always requires as much time as needed to organically get the job done. (Think of novel writers or other artists.) Other types of work operate on “clock time,” and are aligned with scheduled events. (A teacher obeys classroom hours and the semester calendar, for instance. An Amazon warehouse manager knows the number of customer orders that can be fulfilled in an hour.)I don't particularly like the phrase 'creative people' in this article, as I believe everyone is (or at least can be) creative. Having said that, I agree with the sentiment:

Creative people need another scarce commodity: mental space. Working in a large team and constantly collaborating as a group doesn’t allow a person the clarity of mind to solve problems with fresh ingenious ideas. “Alone time or working with just one close collaborator seemed to be the key under the low time pressure conditions,” says Amabile.Source: QuartzCreative people, she adds, “have to be protected. They have to be isolated in a way, from all the other stuff that comes up during a work day. They can’t be called into meetings that are unrelated to this serious problem that they’re trying to address.”