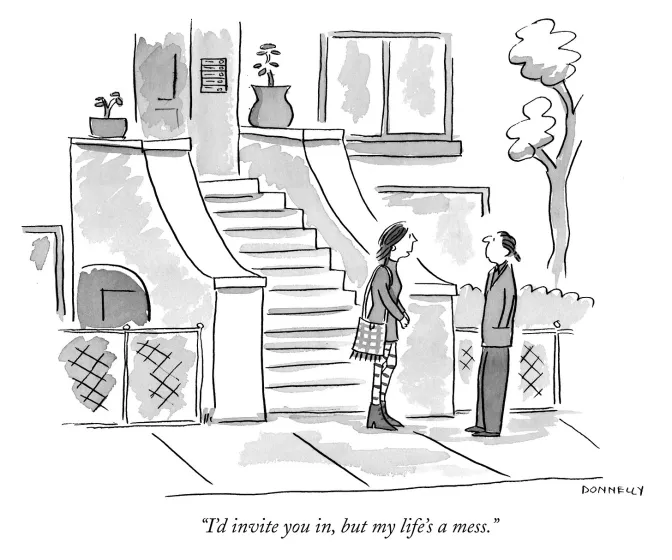

Telling stories using cartoons

Liza Donnelly is a cartoonist for the New Yorker. In this article, which is an output from some preparatory work for a talk she’s preparing, she talks about how the best cartoons work.

I’ve had the privilege of working with Bryan Mathers over the last decade and it really is a fascinating process. In fact, he’s just delivered a bunch of artwork for the work we’re doing around Open Recognition. Check it out here!

Story is everywhere. In single panel cartoons, they have to be kept in one image. It’s tricky and challenging and I love it. I like to say that a single panel cartoon is like a mini stage. The artist is a set designer, choreographer, script writer, costume designer, casting director. Each element in the drawing needs to be necessary for the idea, no more, no less; there are exceptions of course. Some creators are known for a style that is overly detailed and complicated, and that is part of the voice of the artist and contributes to the story. The image is a moment in time, and you have to feel that there is time before the moment you see, and a continuation after that moment. And the characters are well “described” in the execution.Source: Storytelling In Drawing | Seeing Things[…]

Bottom line: story in the best New Yorker cartoons tell us a story about the characters that are in the drawing, and about ourselves. This is why we love them so much—they are fun, entertaining and are about us.

Bad coffee

I love this essay, not because I necessarily agree with it, but because I agree with the vibe of it. It’s from 2019, so it must have come via my social feeds.

Keith Pandolfi used to own a coffee shop which served the best barista-crafted flat whites, etc. in the area. These days he drinks Maxwell House. Likewise, there’s areas of my life in which I’ve gone from being very fussy to not really caring. It’s the letting go that matters.

The best cup of coffee I ever had was the dirty Viennese blend my teenage friends and I would sip out of chipped ceramic mugs at a cafe near the University of Cincinnati while smoking clove cigarettes and listening to Sisters of Mercy records, imagining what it would be like to be older than we were. The best cup of coffee was the one I enjoyed alone each morning during my freshman year at Ohio State, huddled in the back of a Rax restaurant reading the college paper and dealing with the onset of an anxiety disorder that would never quite be cured.Source: The Case for Bad Coffee | Serious Eats[…]

I don’t have memories of… bonding experiences taking place over a flat white at a Manhattan coffee shop or a $5 cup of nitro iced coffee at a Brooklyn cafe. High-end coffee doesn’t usually lend itself to such moments. Instead, it’s something to be fussed over and praised; you talk more about its origin and its roaster, its flavor notes and its brewing method than you talk to the person you’re enjoying it with. Bad coffee is the stuff you make a full pot of on the weekends just in case some friends stop by. It’s what you sip when you’re alone at the mechanic’s shop getting your oil change, thinking about where your life has taken you; what you nurse as you wait for a loved one to get through a tough surgery. It’s the Sanka you share with an elderly great aunt while listening to her tell stories you’ve heard a thousand times before. Bad coffee is there for you. It is bottomless. It is perfect.

Some fairy tales may be 6,000 years old

It’s fascinating to think that children’s stories may have been told and re-told across languages and cultures for millennia. It just goes to show the power of narrative structure!

Fairy tales are transmitted through language, and the shoots and branches of the Indo-European language tree are well-defined, so the scientists could trace a tale's history back up the tree—and thus back in time. If both Slavic languages and Celtic languages had a version of Jack and the Beanstalk (and the analysis revealed they might), for example, chances are the story can be traced back to the "last common ancestor." That would be the Proto-Western-Indo-Europeans from whom both lineages split at least 6800 years ago. The approach mirrors how an evolutionary biologist might conclude that two species came from a common ancestor if their genes both contain the same mutation not found in other modern animals.Source: Some fairy tales may be 6000 years old | AAAS[…]

Tehrani says that the successful fairy tales may persist because they’re “minimally counterintuitive narratives.” That means they all contain some cognitively dissonant elements—like fantastic creatures or magic—but are mostly easy to comprehend. Beauty and the Beast, for example, contains a man who has been magically transformed into a hideous creature, but it also tells a simple story about family, romance, and not judging people based on appearance. The fantasy makes these tales stand out, but the ordinary elements make them easy to understand and remember. This combination of strange, but not too strange, Tehrani says, may be the key to their persistence across millennia.