- Our inability to distinguish between confidence and competence

- Our love of charasmatic individuals

- The allure of “people with grandiose visions that tap into our own narcissism”

Xero starts using consent-based decision making

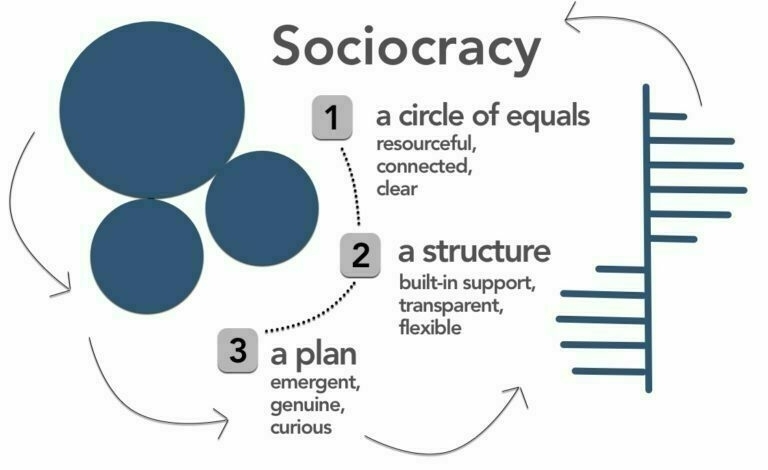

Sociocracy, which includes consent-based decision making, is something we use at WAO. I’ve written about it several times on my personal blog as well as here.

It looks like the approach is working not just for yogurt-knitting vegans who work in co-operatives, but hard-nose businesses like Xero. Who knew?

For the past year, I’ve been lucky enough to work on a big technology project at Xero, where I spend much of my time supporting the leadership team. But it didn’t take long for me to realise that when you have a large number of people bringing their own perspectives and opinions into a complex situation, consensus is going to be challenging (if not impossible).Source: Making better, faster decisions that are good enough for now | Bonnie SlaterSo I decided to introduce consent-based decision making to the leadership team. It’s something that a colleague introduced me to last year. It’s had such a positive impact on my work that I thought I’d share more about it, in the hope that you can use this simple technique in your team as well.

How you do anything is how you do everything

So said Derek Sivers, although I suspect that, originally, it's probably a core principle of Zen Buddhism. In this article I want to talk about management and leadership. But also about emotional intelligence and integrity.

I currently spend part of my working life as a Product Manager. At some organisations, this means that you're in charge of the budget, and pull in colleagues from different disciplines. For example, a designer you're working with on a particular project might report to the Head of UX. Matrix-style management and internal budgeting keeps track of everything.

This approach can get complicated so, at other companies (like the one I'm working with), the Product Manager manages both people and product. It's a lot of work, as both can be complicated.

I think I'm OK at managing people, and other people say I'm good at it, but it's not my favourite thing in the world to do.

That's why, when hiring, I try to do so in one of three ways. Ideally, I want to hire people with whom at least one member of the existing team has already worked and can vouch for. If that doesn't work, then I'm looking for people vouched for my the networks of which the team are part. Failing that, I'm trying to find people who don't wait for direction, but know how to get on with things that need doing.

It's an approach I've developed from the work of Laura Thomson. She's a former colleague at Mozilla, and an advocate of a chaordic style of management and self-organising ducks:

Instead of having ‘all your ducks in a row’ the analogy in chaordic management is to have ‘self-organising ducks’. The idea is to give people enough autonomy, knowledge and skill to be able to do the management themselves.

As I've said before, the default way of organising human beings is hierarchy. That doesn't mean it's the best way. Hierachy tends to lean on processes, paperwork and meetings to 'get things done' but even a cursory glance at Open Source projects shows that all of this isn't strictly necessary.

Last week, a new-ish member of the team said that I can be "too nice". I'm still processing that and digging into what they meant, but I then ended up reading an article by Roddy Millar for Fast Company entitled Here’s why being likable may make you a less effective leader.

It's a slightly oddly-framed article that quotes Prof. Karen Cates from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management :

Leaders should not put likability above effectiveness. There are times when the humor and smiles need to go and a let’s-get-this-done approach is required. Cates goes further: “Even the ‘nasty boss approach’ can be really effective—but in short, small doses—to get everyone’s attention and say ‘Hey, we’ve got to make some changes around here.’ You can then create—with an earnest approach—that more likable persona as you move forward. Likability is a good thing to have in your leadership toolkit, but it shouldn’t be the biggest hammer in the box.”

Roddy Millar

I think there's a difference between 'trying to be likeable' and 'treating your colleagues with dignity and respect'.

If you're being nice to be just to liked by your team, you're probably doing it wrong. It's a bit like, back when I was teaching, teachers who wanted to be liked by the kids they taught.

The other approach is to simply treat the people around you with dignity and respect, realising that all of human life involves suffering, so let's not add to the burden through our everyday working lives.

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The above is one of my favourite quotations. We don't need to crack the whip or wield some kind of totem of hierarchical power over other people. We just need to ensure people are in the right place (physically and emotoinally), with the right things (tools, skills, and information) to get things done.

In managers are for caring, Harold Jarche points a finger at hierarchical organisations, stating that they are "what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator".

Jarche wonders instead what would happen if they were structured more like communities of practice?

What would an organization look like with looser hierarchies and stronger networks? A lot more human, retrieving some of the intimacy and cooperation of tribal groups. We already have other ways of organizing work. Orchestras are not teams, and neither are jazz ensembles. There may be teamwork on a theatre production but the cast is not a team. It is more like a community of practice, with strong and weak social ties.

Harold Jarche

I think part of the problem, to be honest, is emotional intelligence, or rather the lack of it, in many organisations.

Unfortunately, the way to earn more money in organisations is to start managing people. Which is fine for the subset of people who have the skills to be able to handle this. For others, it's a frustrating experience that takes them away from doing the work.

For TED Ideas, organisational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic asks Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? And what can we do about it? He lists three reasons why we have so many incompetent (male) leaders:

He suggests three ways to fix this. The other two are all well and good, but I just want to focus on the first solution he suggests:

The first solution is to follow the signs and look for the qualities that actually make people better leaders. There is a pathological mismatch between the attributes that seduce us in a leader and those that are needed to be an effective leader. If we want to improve the performance of our leaders, we should focus on the right traits. Instead of falling for people who are confident, narcissistic and charismatic, we should promote people because of competence, humility and integrity. Incidentally, this would also lead to a higher proportion of female than male leaders — large-scale scientific studies show that women score higher than men on measures of competence, humility and integrity. But the point is that we would significantly improve the quality of our leaders.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

The best leaders I've worked for exhibited high levels of emotional intelligence. Most of them were women.

Developing emotional intelligence is difficult and goodness knows I'm no expert. What I think we perhaps need to do is to remove our corporate dependency on hierarchy. In hierarchies, emotion and trust is removed as an impediment to action.

However, in my experience, hierarchy is inherently patriarchal and competitive. It's not something that's necessarily useful in every industry in the 21st century. And hierarchies are not places that I, and people like me, particularly thrive.

Instead, I think we require trust-based ways of organising — ways that emphasis human relationships. I think these are also more conducive to human flourishing.

Right now, approaches such as sociocracy take a while to get our collective heads around as they're opposed to our "default operating system" of hierarchy. However, over time I think we'll see versions of this becoming the norm, as it becomes ever easier to co-ordinate people at a distance.

To sum up, what it means to be an effective leader is changing. Returning to the article cited above by Harold Jarche, he writes:

Hierarchical teams are what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator. In a creative economy, the unity of hierarchical teams is counter-productive, as it shuts off opportunities for serendipity and innovation. In a complex and networked economy workers need more autonomy and managers should have less control.

Harold Jarche

Many people no longer live in a world of the 'permanent job' and 'career ladder'. What counts as success for them is not necessarily a steadily-increasing paycheck, but measures such as social justice or 'making a dent in the universe'. This is where hierarchy fails, and where emergent, emotionally-intelligent leaders with teams of self-organising ducks, thrive.

Do not impose one's own standard on the work of others. Mutual moderation and cooperation will proffer better results.

I think I must have come across the above saying from Hsing Yun via Mayel de Borniol. It captures some of what I want to discuss in this article which centres around decision-making within organisations.

Let's start with a great article from Roman Imankulov from Doist. He looks to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)'s approach, as enshrined in a document from 2014, explaining their 'rough consensus' approach:

Rough consensus isn’t majority rule. It’s okay to go ahead with a solution that may not look like the best choice for everyone or even the majority. "Not the best choice" means that you believe there is a better way to solve the problem, but you accept that this one will work too. That type of feedback should be welcomed, but it shouldn’t be allowed to slow down a decision.

Roman Imankulov

If they try hard enough, everyone can come up with a reason why an idea or approach won't work. My experience is that many middle-aged white men see it as their sworn duty to come up with as many of those reasons as possible 🙄

What the IETF calls 'rough consensus' I think I'd probably call 'alignment'. You don't all have to agree that a proposal is without problems, but those problems should be surmountable. Within CoTech, a network of co-operatives to which We Are Open belongs, we use Loomio. It has a number of decision tools, including the 'proposal':

As you can see, there's the ability for anyone to 'Block' a proposal, meaning that it can't be passed in its current form. People can 'Abstain' if there's a conflict of interest, or if they don't feel like they've got enough experience or expertise. Note that it's entirely possible for someone to 'Disagree' and the motion to still go ahead.

What I like about Loomio is a tool is that it focuses on decision-making. It's not about endless discussion and debate, but about having a bias towards action. You can separate the planning process from the implementation stage:

Rough consensus doesn’t mean that we don’t aim for perfection in the actual implementation of the solution. When implementing, we should always aim for technical excellence. Commitment to the implementation is often what makes a solution the right one. (This is similar to Amazon’s "disagree and commitment" philosophy.)

Roman Imankulov

I can't, by my nature, stand hierarchy. Unfortunately, it's the default operating system of most organisations, and despite our best efforts, we haven't got a one-size-fits-all alternative to it. I think this is partly because nobody has to teach you how hierarchy works.

Over the weekend, while we were walking in the Lake District, Tom Broughton and I were discussing sociocracy:

Sociocracy, also known as dynamic governance, is a system of governance which seeks to achieve solutions that create harmonious social environments as well as productive organizations and businesses. It is distinguished by the use of consent rather than majority voting in decision-making, and decision-making after discussion by people who know each other.

Wikipedia

Tom's a Quaker and so used to consent-based decision-making. I explained that we'd asked Outlandish (a CoTech member) to run a sociocratic design sprint to kick off our work around MoodleNet. It was based on the Google design sprint approach, but — as Kayleigh from Outlandish points out — featured an important twist:

We decided to remove the ‘decider’ role that a Google Sprint employs. We weren’t comfortable with the responsibility and authority of decisions sitting with one person, and having spent a few years practising sociocracy already, it just wouldn’t have felt right.

[...]

Martin, Moodle’s CEO and founder joined us for the duration of the sprint. While Martin naturally had the most expertise in the domain, the most ‘skin in the game’ and the had done the most background thinking sociocracy meant that he still needed to convince the rest of the sprint team as to why his ideas were best, and take on board other suggestions and compromises. We feel that it led to better outputs at each stage of the design sprint.

Kayleigh Walsh

It was the first time I'd seen a CEO give up their hierarchical power in the interests of ensuring that we designed something that could be the best it could possibly be. In fact, that week last May is probably one of the highlights of my career to date.

That was one week into which was poured a lot of time, attention, and money. But what if you want to practise something like sociocracy on a day-to-day basis? You have to think about structure of organisations, as there's no such thing as 'structureless' group:

Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved. The very fact that we are individuals, with different talents, predispositions, and backgrounds makes this inevitable. Only if we refused to relate or interact on any basis whatsoever could we approximate structurelessness -- and that is not the nature of a human group.

Jo Freeman

It's only within the last year that I've discovered left-libertarianism as a coherent political and social philosophy that helps me reconcile two things that I've previously found difficult. On the one hand, I believe in a small state. On the other, I believe we have a duty to one another and should help out wherever possible.

Left-libertarianism, also known as left-wing libertarianism, names several related yet distinct approaches to political and social theory which stress both individual freedom and social equality. In its classical usage, left-libertarianism is a synonym for anti-authoritarian varieties of left-wing politics such as libertarian socialism which includes anarchism and libertarian Marxism among others.

[...]

While maintaining full respect for personal property, left-libertarians are skeptical of or fully against private ownership of natural resources, arguing in contrast to right-libertarians that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights and maintain that natural resources (raw land, oil, gold, the electromagnetic spectrum, air-space and so on) should be held in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively. Those left-libertarians who support private property do so under occupation and use property norms or under the condition that recompense is offered to the local or even global community.

Wikipedia

In other words, you don't have to be a Marxist, communist, or anarchist to be a left-libertarian. It means you can start from a basis of personal autonomy, but end with an egalitarian approach to the world where resources (especially natural resources) are collectively owned.

To me, this is the position from which we should start when we think about decision-making within organisations. First of all, we should ask: who owns the organisation? Why? Second, we should consider how the organisation should be structured. Ten layers of management might be bad, but so is a completely flat structure for 700 people. And finally, we should think about appropriate mechanisms for decision-making.

The usual criticisms of sociocracy and other consent-based decision-making systems is that they are too slow, that they don't work in practice. In my experience, by participating in the Outlandish/Moodle design sprint, witnessing a Mozilla Festival session in which participants quickly got up-to-speed on sociocracy, and through CoTech gatherings (both online and offline), I'd say sociocracy is a viable solution.

The best decisions aren't ones where you have all of the information to hand. That's impossible. The best decisions are based on trust and consent.

As I get older, I'm realising that the best way we can improve the world is to improve its governance. It's not that we haven't got extremely talented people in the world, it's that we don't always know how to make good decision. I'd like to change that.

Rethinking hierarchy

This study featured on the blog of the Stanford Graduate School of Business talks about the difference between hierarchical and non-hierarchical structures. It cites work by Lisanne van Bunderen from University of Amsterdam, who found that egalitarianism seemed to lead to better performance:

Context, of course, is vital. One place where hierarchy and a command-and-control approach seems impotant is in high stakes situations such as the battlefield or hospital operating theatres during delicate operations. Lindred Greer, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, nevertheless believes that, even in these situations, the amount of hierarchy can be reduced:“The egalitarian teams were more focused on the group because they felt like ‘we’re in the same boat, we have a common fate,’” says van Bunderen. “They were able to work together, while the hierarchical team members felt a need to fend for themselves, likely at the expense of others.”

In some cases, hierarchy is an unavoidable part of the work. Greer is currently studying the interaction between surgeons and nurses, and surgeons lead by necessity. “If you took the surgeon out of the operating room, you would have some issues,” she says. But surgeons’ dominance in the operating room can also be problematic, creating dysfunctional power dynamics. To help solve this problem, Greer believes that the expression of hierarchy can be moderated. That is, surgeons can learn to behave in a way that’s less hierarchical.While hierarchy is necessary in some situations, what we need is a more fluid approach to organising, as I've written about recently. The article gives the very practical example of Navy SEALs:

Like the article's author, I'm still looking for something that's going to gain more traction than Holacracy. Perhaps the sociocratic approach could work well, but does require people to be inducted into it. After all, hierarchy and capitalism is what we're born into these days. It feels 'natural' to people.Navy SEALS exemplify this idea. Strict hierarchy dominates out in the field: When a leader says go left, they go left. But when the team returns for debrief, “they literally leave their stripes at the door,” says Greer. The hierarchy disappears; nobody is a leader, nobody a follower. “They fluidly shift out of these hierarchical structures,” she says. “It would be great if business leaders could do this too: Shift from top-down command to a position in which everyone has a say.” Importantly, she reiterated, this kind of change is not only about keeping employees happy, but also about enhancing performance and benefiting the bottom line.

Source: Stanford Graduate School of Business (via Stowe Boyd)