- Study shows some political beliefs are just historical accidents (Ars Technica) — "Obviously, these experiments aren’t exactly like the real world, where political leaders can try to steer their parties. Still, it’s another way to show that some political beliefs aren’t inviolable principles—some are likely just the result of a historical accident reinforced by a potent form of tribal peer pressure. And in the early days of an issue, people are particularly susceptible to tribal cues as they form an opinion."

- Please, My Digital Archive. It’s Very Sick. (Lapham's Quarterly) — "An archivist’s dream is immaculate preservation, documentation, accessibility, the chance for our shared history to speak to us once more in the present. But if the preservation of digital documents remains an unsolvable puzzle, ornery in ways that print materials often aren’t, what good will our archiving do should it become impossible to inhabit the world we attempt to preserve?"

- So You’re 35 and All Your Friends Have Already Shed Their Human Skins (McSweeney's) — "It’s a myth that once you hit 40 you can’t slowly and agonizingly mutate from a human being into a hideous, infernal arachnid whose gluttonous shrieks are hymns to the mad vampire-goddess Maggorthulax. You have time. There’s no biological clock ticking. The parasitic worms inside you exist outside of our space-time continuum."

- Investing in Your Ordinary Powers (Breaking Smart) — "The industrial world is set up to both encourage and coerce you to discover, as early as possible, what makes you special, double down on it, and build a distinguishable identity around it. Your specialness-based identity is in some ways your Industrial True Name. It is how the world picks you out from the crowd."

- Browser Fingerprinting: An Introduction and the Challenges Ahead (The Tor Project) — "This technique is so rooted in mechanisms that exist since the beginning of the web that it is very complex to get rid of it. It is one thing to remove differences between users as much as possible. It is a completely different one to remove device-specific information altogether."

- What is a Blockchain Phone? The HTC Exodus explained (giffgaff) — "HTC believes that in the future, your phone could hold your passport, driving license, wallet, and other important documents. It will only be unlockable by you which makes it more secure than paper documents."

- Debate rages in Austria over enshrining use of cash in the constitution (EURACTIV) — "Academic and author Erich Kirchler, a specialist in economic psychology, says in Austria and Germany, citizens are aware of the dangers of an overmighty state from their World War II experience."

- Cory Doctorow: DRM Broke Its Promise (Locus magazine) — "We gave up on owning things – property now being the exclusive purview of transhuman immortal colony organisms called corporations – and we were promised flexibility and bargains. We got price-gouging and brittleness."

- Five Books That Changed Me In One Summer (Warren Ellis) — "I must have been around 14. Rayleigh Library and the Oxfam shop a few doors down the high street from it, which someone was clearly using to pay things forward and warp younger minds."

- Why Do You Grab Your Bag When Running Off a Burning Plane? (The New York Times) — it turns out that it's less of a decision, more of an impulse.

- If a house was designed by machine, how would it look? (BBC Business) — lighter, more efficient buildings.

- Playdate is an adorable handheld with games from the creators of Qwop, Katamari, and more (The Verge) — a handheld console with a hand crank that's actually used for gameplay instead of charging!

- The true story of the worst video game in history (Engadget) — it was so bad they buried millions of unsold cartridges in the desert.

- E Ink Smartphones are the big new trend of 2019 (Good e-Reader) — I've actually also own a regular phone with an e-ink display, so I can't wait for this to be a thing.

- Download all the information Google has on you.

- Try not to let your smart toaster take down the internet.

- Ensure your AirDrop settings are dick-pic-proof.

- Secure your old Yahoo account.

- 1234 is not an acceptable password.

- Check if you have been pwned.

- Be aware of personalised pricing.

- Say hi to the NSA guy spying on you via your webcam.

- Turn off notifications for anything that’s not another person speaking directly to you.

- Never put your kids on the public internet.

- Leave your phone in your pocket or face down on the table when you’re with friends.

- Sometimes it’s worth just wiping everything and starting over.

- An Echo is fine, but don’t put a camera in your bedroom.

- Have as many social-media-free days in the week as you have alcohol-free days.

- Retrain your brain to focus.

- Don’t let the algorithms pick what you do.

- Do what you want with your data, but guard your friends’ info with your life.

- Finally, remember your privacy is worth protecting.

The rich are scared we're going to eat them

I’m reading Roots at the moment, the novel by Alex Haley about an African man captured and sold into slavery. I’m at the point of the story where his daughter’s ‘massa’ gets spooked about a slave uprising.

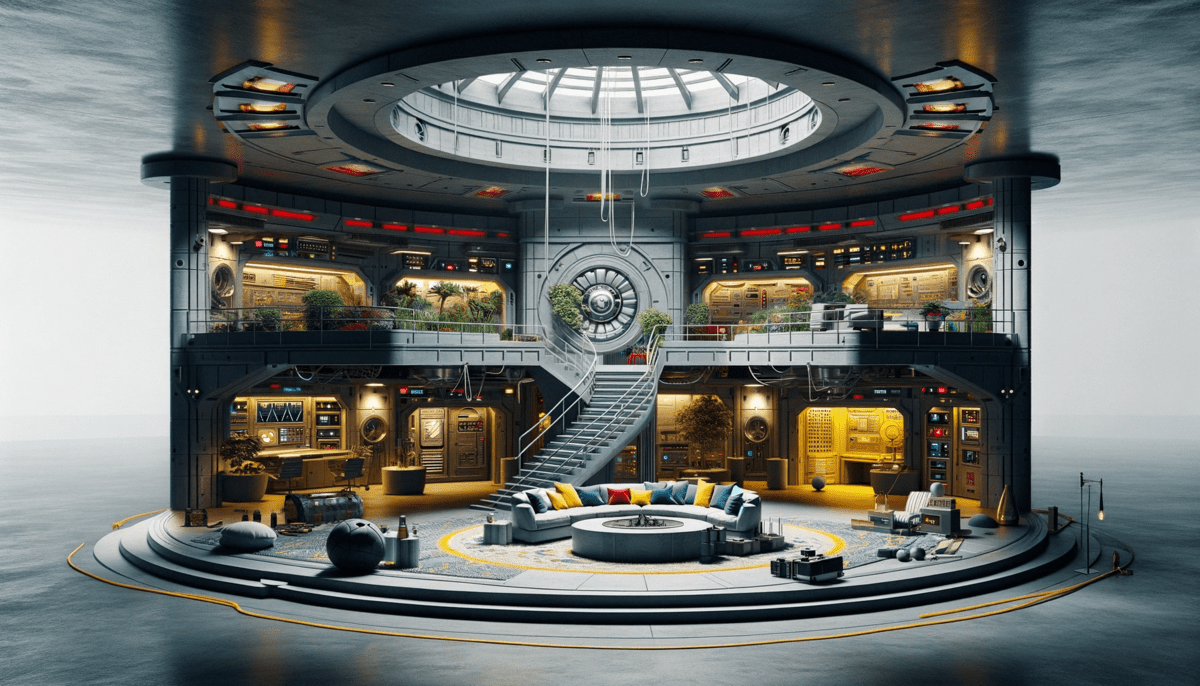

It’s difficult not to draw parallels when reading about an apparent trend towards billionaires building luxury ‘bunkers’ with supplies and blast-proof doors. They would do well to worry, given the amount of inequality in the world.

One prevalent speculation that has circulated suggests that these billionaires might possess knowledge beyond the scope of the average person. The idea is that their vast resources are being channeled into constructing secure retreats as a form of preparation for potential global upheavals or crises. This speculation plays into the notion that these elite individuals may be privy to information that the general public is not, prompting them to take unprecedented measures to safeguard their well-being. Moreover, some fear that the escalating global tensions and geopolitical uncertainties may be driving these billionaires to prepare for worst-case scenarios, including the prospect of war.Source: Zuckerberg's Bunker Plans Fuel Speculation on Billionaires Building Bunkers | Decode Today

Image: DALL-E 3

Assume that your devices are compromised

I was in Catalonia in 2017 during the independence referendum. The way that people were treated when trying to exercise democratic power I still believe to be shameful.

These days, I run the most secure version of an open operating system on my mobile device that I can. And yet I still need to assume it's been compromised.

In Catalonia, more than sixty phones—owned by Catalan politicians, lawyers, and activists in Spain and across Europe—have been targeted using Pegasus. This is the largest forensically documented cluster of such attacks and infections on record. Among the victims are three members of the European Parliament, including Solé. Catalan politicians believe that the likely perpetrators of the hacking campaign are Spanish officials, and the Citizen Lab’s analysis suggests that the Spanish government has used Pegasus. A former NSO employee confirmed that the company has an account in Spain. (Government agencies did not respond to requests for comment.) The results of the Citizen Lab’s investigation are being disclosed for the first time in this article. I spoke with more than forty of the targeted individuals, and the conversations revealed an atmosphere of paranoia and mistrust. Solé said, “That kind of surveillance in democratic countries and democratic states—I mean, it’s unbelievable.”

[...]

[T]here is evidence that Pegasus is being used in at least forty-five countries, and it and similar tools have been purchased by law-enforcement agencies in the United States and across Europe. Cristin Flynn Goodwin, a Microsoft executive who has led the company’s efforts to fight spyware, told me, “The big, dirty secret is that governments are buying this stuff—not just authoritarian governments but all types of governments.”

[...]

The Citizen Lab’s researchers concluded that, on July 7, 2020, Pegasus was used to infect a device connected to the network at 10 Downing Street, the office of Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. A government official confirmed to me that the network was compromised, without specifying the spyware used. “When we found the No. 10 case, my jaw dropped,” John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at the Citizen Lab, recalled. “We suspect this included the exfiltration of data,” Bill Marczak, another senior researcher there, added. The official told me that the National Cyber Security Centre, a branch of British intelligence, tested several phones at Downing Street, including Johnson’s. It was difficult to conduct a thorough search of phones—“It’s a bloody hard job,” the official said—and the agency was unable to locate the infected device. The nature of any data that may have been taken was never determined.

Source: How Democracies Spy On Their Citizens | The New Yorker

How to be a darknet drug lord

Wow, who knew how difficult it was to be a criminal? Found via HN.

You're an aspiring drug kingpin. Go out and pay cash for another computer. It doesn't have to be the best or most expensive, but it needs to be able to run Linux. For additional safety, don't lord over your new onion empire from your mother's basement, or any location normally associated with you. Leave your phone behind when you head out to manage your enterprise so you aren't tracked by cell towers. Last but not least for this paragraph, don't talk about the same subjects across identities and take counter-measures to alter your writing style.Source: So, you want to be a darknet drug lord… | nachash[…]

Disinformation is critical to your continued freedom. Give barium meat tests to your contacts liberally. It doesn’t matter if they realize they’re being tested. Make sure that if you’re caught making small talk, you inject false details about yourself and your life. You don’t want to be like Ernest Lehmitz, a German spy during World War II who sent otherwise boring letters about himself containing hidden writing about ship movements. He got caught because the non-secret portion of his letters gave up various minor personal details the FBI correlated and used to find him after intercepting just 12 letters. Spreading disinformation about yourself takes time, but after a while the tapestry of deceptions will practically weave itself.

[…]

Take-away: If you rely only on tor to protect yourself, you’re going to get owned and people like me are going to laugh at you. Remember that someone out there is always watching, and know when to walk away. Do try to stay safe while breaking the law. In the words of Sam Spade, “Success to crime!"

Securing your digital life

Usually, guides to securing your digital life are very introductory and basic. This one from Ars Technica, however, is a bit more advanced. I particularly appreciate the advice to use authenticator apps for 2FA.

Remember, if it’s inconvenient for you it’s probably orders of magnitude more inconvenient for would-be attackers. To get into one of my cryptocurrency accounts, for example, I’ve set it so I need a password and three other forms of authentication.

Overkill? Probably. But it dramatically reduces the likelihood that someone else will make off with my meme stocks…

Security measures vary. I discovered after my Twitter experience that setting up 2FA wasn’t enough to protect my account—there’s another setting called “password protection” that prevents password change requests without authentication through email. Sending a request to reset my password and change the email account associated with it disabled my 2FA and reset the password. Fortunately, the account was frozen after multiple reset requests, and the attacker couldn’t gain control.Source: Securing your digital life, part two: The bigger picture—and special circumstances | Ars TechnicaThis is an example of a situation where “normal” risk mitigation measures don’t stack up. In this case, I was targeted because I had a verified account. You don’t necessarily have to be a celebrity to be targeted by an attacker (I certainly don’t think of myself as one)—you just need to have some information leaked that makes you a tempting target.

For example, earlier I mentioned that 2FA based on text messages is easier to bypass than app-based 2FA. One targeted scam we see frequently in the security world is SIM cloning—where an attacker convinces a mobile provider to send a new SIM card for an existing phone number and uses the new SIM to hijack the number. If you’re using SMS-based 2FA, a quick clone of your mobile number means that an attacker now receives all your two-factor codes.

Additionally, weaknesses in the way SMS messages are routed have been used in the past to send them to places they shouldn’t go. Until earlier this year, some services could hijack text messages, and all that was required was the destination phone number and $16. And there are still flaws in Signaling System 7 (SS7), a key telephone network protocol, that can result in text message rerouting if abused.

Friday feudalism

Check out these things I discovered this week, and wanted to pass along:

Friday fumblings

These were the things I came across this week that made me smile:

Image via Why WhatsApp Will Never Be Secure (Pavel Durov)

Blockchains: not so 'unhackable' after all?

As I wrote earlier this month, blockchain technology is not about trust, it’s about distrust. So we shouldn’t be surprised in such an environment that bad actors thrive.

Reporting on a blockchain-based currency (‘cryptocurrency’) hack, MIT Technology Review comment:

We shouldn’t be surprised. Blockchains are particularly attractive to thieves because fraudulent transactions can’t be reversed as they often can be in the traditional financial system. Besides that, we’ve long known that just as blockchains have unique security features, they have unique vulnerabilities. Marketing slogans and headlines that called the technology “unhackable” were dead wrong.The more complicated something is, the more you have to trust technological wizards to verify something is true, then the more problems you're storing up:

But the more complex a blockchain system is, the more ways there are to make mistakes while setting it up. Earlier this month, the company in charge of Zcash—a cryptocurrency that uses extremely complicated math to let users transact in private—revealed that it had secretly fixed a “subtle cryptographic flaw” accidentally baked into the protocol. An attacker could have exploited it to make unlimited counterfeit Zcash. Fortunately, no one seems to have actually done that.It's bad enough when people lose money through these kinds of hacks, but when we start talking about programmable blockchains (so-called 'smart contracts') then we're in a whole different territory.

A smart contract is a computer program that runs on a blockchain network. It can be used to automate the movement of cryptocurrency according to prescribed rules and conditions. This has many potential uses, such as facilitating real legal contracts or complicated financial transactions. Another use—the case of interest here—is to create a voting mechanism by which all the investors in a venture capital fund can collectively decide how to allocate the money.Human culture is dynamic and ever-changing, it's not something we should be hard-coding. And it's certainly not something we should be hard-coding based on the very narrow worldview of those who understand the intricacies of blockchain technology.

It’s particularly delicious that it’s the MIT Technology Review commenting on all of this, given that they’ve been the motive force behind Blockcerts, “the open standard for blockchain credentials” (that nobody actually needs).

Source: MIT Technology Review

Blockchains: not so 'unhackable' after all?

As I wrote earlier this month, blockchain technology is not about trust, it’s about distrust. So we shouldn’t be surprised in such an environment that bad actors thrive.

Reporting on a blockchain-based currency (‘cryptocurrency’) hack, MIT Technology Review comment:

We shouldn’t be surprised. Blockchains are particularly attractive to thieves because fraudulent transactions can’t be reversed as they often can be in the traditional financial system. Besides that, we’ve long known that just as blockchains have unique security features, they have unique vulnerabilities. Marketing slogans and headlines that called the technology “unhackable” were dead wrong.The more complicated something is, the more you have to trust technological wizards to verify something is true, then the more problems you're storing up:

But the more complex a blockchain system is, the more ways there are to make mistakes while setting it up. Earlier this month, the company in charge of Zcash—a cryptocurrency that uses extremely complicated math to let users transact in private—revealed that it had secretly fixed a “subtle cryptographic flaw” accidentally baked into the protocol. An attacker could have exploited it to make unlimited counterfeit Zcash. Fortunately, no one seems to have actually done that.It's bad enough when people lose money through these kinds of hacks, but when we start talking about programmable blockchains (so-called 'smart contracts') then we're in a whole different territory.

A smart contract is a computer program that runs on a blockchain network. It can be used to automate the movement of cryptocurrency according to prescribed rules and conditions. This has many potential uses, such as facilitating real legal contracts or complicated financial transactions. Another use—the case of interest here—is to create a voting mechanism by which all the investors in a venture capital fund can collectively decide how to allocate the money.Human culture is dynamic and ever-changing, it's not something we should be hard-coding. And it's certainly not something we should be hard-coding based on the very narrow worldview of those who understand the intricacies of blockchain technology.

It’s particularly delicious that it’s the MIT Technology Review commenting on all of this, given that they’ve been the motive force behind Blockcerts, “the open standard for blockchain credentials” (that nobody actually needs).

Source: MIT Technology Review

Configuring your iPhone for productivity (and privacy, security?)

At an estimated read time of 70 minutes, though, this article is the longest I’ve seen on Medium! It includes a bunch of advice from ‘Coach Tony’, the CEO of Coach.me, about how he uses his iPhone, and perhaps how you should too:

The iPhone could be an incredible tool, but most people use their phone as a life-shortening distraction device.As an aside, I appreciate the way he sets up different ways to read the post, from skimming the headlines through to reading the whole thing in-depth.However, if you take the time to follow the steps in this article you will be more productive, more focused, and — I’m not joking at all — live longer.

Practically every iPhone setup decision has tradeoffs. I will give you optimal defaults and then trust you to make an adult decision about whether that default is right for you.

However, the problem is that for a post that the author describes as a ‘very very complete’ guide to configuring your iPhone to ‘work for you, not against you’, it doesn’t go into enough depth about privacy and security for my liking. I’m kind of tired of people thinking that using a password manager and increasing your lockscreen password length is enough.

For example, Coach Tony talks about basically going all-in on Google Cloud. When people point out the privacy concerns of doing this, he basically uses the tinfoil hat defence in response:

Moving to the Google cloud does trade privacy for productivity. Google will use your data to advertise to you. However, this is a productivity article. If you wish it were a privacy article, then use Protonmail. Last, it’s not consistent that I have you turn off Apple’s ad tracking while then making yourself fully available to Google’s ad tracking. This is a tradeoff. You can turn off Apple’s tracking with zero downside, so do it. With Google, I think it’s worthwhile to use their services and then fight ads in other places. The Reader feature in Safari basically hides most Google ads that you’d see on your phone. On your computer, try an ad blocker.It's all very well saying that it's a productivity article rather than a privacy article. But it's 2018, you need to do both. Don't recommend things to people that give them gains in one area but causes them new problems in others.

That being said, I appreciate Coach Tony’s focus on what I would call ‘notification literacy’. Perhaps read his article, ignore the bits where he suggests compromising your privacy, and follow his advice on configuring your device for a calmer existence.

Source: Better Humans

Survival in the age of surveillance

The Guardian has a list of 18 tips to ‘survive’ (i.e. be safe) in an age where everyone wants to know everything about you — so that they can package up your data and sell it to the highest bidder.

On the internet, the adage goes, nobody knows you’re a dog. That joke is only 15 years old, but seems as if it is from an entirely different era. Once upon a time the internet was associated with anonymity; today it is synonymous with surveillance. Not only do modern technology companies know full well you’re not a dog (not even an extremely precocious poodle), they know whether you own a dog and what sort of dog it is. And, based on your preferred category of canine, they can go a long way to inferring – and influencing – your political views.Mozilla has pointed out in a recent blog post that the containers feature in Firefox can increase your privacy and prevent 'leakage' between tabs as you navigate the web. But there's more to privacy and security than just that.

Here’s the Guardian’s list:

A bit of a random list in places, but useful all the same.

Source: The Guardian

The security guide as literary genre

I stumbled across this conference presentation from back in January by Jeffrey Monro, “a doctoral student in English at the University of Maryland, College Park, where [he studies] the textual and material histories of media technologies”.

It’s a short, but very interesting one, taking a step back from the current state of play to ask what we’re actually doing as a society.

Over the past year, in an unsurprising response to a host of new geopolitical realities, we’ve seen a cottage industry of security recommendations pop up in venues as varied as The New York Times, Vice, and even Teen Vogue. Together, these recommendations form a standard suite of answers to some of the most messy questions of our digital lives. “How do I stop advertisers from surveilling me?” “How do I protect my internet history from the highest bidder?” And “how do I protect my privacy in the face of an invasive or authoritarian government?”It's all very well having a plethora of guides to secure ourselves against digital adversaries, but this isn't something that we need to really think about in a physical setting within the developed world. When I pop down to the shops, I don't think about the route I take in case someone robs me at gunpoint.

So Monro is thinking about these security guides as a kind of ‘literary genre’:

I’m less interested in whether or not these tools are effective as such. Rather, I want to ask how these tools in particular orient us toward digital space, engage imaginaries of privacy and security, and structure relationships between users, hackers, governments, infrastructures, or machines themselves? In short: what are we asking for when we construe security as a browser plugin?There's a wider issue here about the pace of digital interactions, security theatre, and most of us getting news from an industry hyper-focused on online advertising. A recent article in the New York Times was thought-provoking in that sense, comparing what it's like going back to (or in some cases, getting for the first time) all of your news from print media.

We live in a digital world where everyone’s seemingly agitated and angry, all of the time:

The increasing popularity of these guides evinces a watchful anxiety permeating even the most benign of online interactions, a paranoia that emerges from an epistemological collapse of the categories of “private” and “public.” These guides offer a way through the wilderness, techniques by which users can harden that private/public boundary.The problem with this 'genre' of security guide, says Monro, is that even the good ones from groups like EFF (of which I'm a member) make you feel like locking down everything. The problem with that, of course, is that it's very limiting.

Communication, by its very nature, demands some dimension of insecurity, some material vector for possible attack. Communication is always already a vulnerable act. The perfectly secure machine, as Chun notes, would be unusable: it would cease to be a computer at all. We can then only ever approach security asymptotically, always leaving avenues for attack, for it is precisely through those avenues that communication occurs.I'm a great believer in serendipity, but the problem with that from a technical point of view is that it increases my attack surface. It's a source of tension that I actually feel most days.

There is no room, or at least less room, in a world of locked-down browsers, encrypted messaging apps, and verified communication for qualities like serendipity or chance encounters. Certainly in a world chock-full with bad actors, I am not arguing for less security, particularly for those of us most vulnerable to attack online... But I have to wonder how our intensive speculative energies, so far directed toward all possibility for attack, might be put to use in imagining a digital world that sees vulnerability as a value.At the end of the day, this kind of article serves to show just how different our online, digital environment is from our physical reality. It's a fascinating sideways look, looking at the security guide as a 'genre'. A recommended read in its entirety — and I really like the look of his blog!

Source: Jeffrey Moro

More haste, less speed

In the last couple of years, there’s been a move to give names to security vulnerabilities that would be otherwise too arcane to discuss in the mainstream media. For example, back in 2014, Heartbleed, “a security bug in the OpenSSL cryptography library, which is a widely used implementation of the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol”, had not only a name but a logo.

The recent media storm around the so-called ‘Spectre’ and ‘Meltdown’ shows how effective this approach is. It also helps that they sound a little like James Bond science fiction.

In this article, Zeynep Tufekci argues that the security vulnerabilities are built on our collective desire for speed:

We have built the digital world too rapidly. It was constructed layer upon layer, and many of the early layers were never meant to guard so many valuable things: our personal correspondence, our finances, the very infrastructure of our lives. Design shortcuts and other techniques for optimization — in particular, sacrificing security for speed or memory space — may have made sense when computers played a relatively small role in our lives. But those early layers are now emerging as enormous liabilities. The vulnerabilities announced last week have been around for decades, perhaps lurking unnoticed by anyone or perhaps long exploited.Helpfully, she gives a layperson's explanation of what went wrong with these two security vulnerabilities:

Right now, she argues, systems have to employ more and more tricks to squeeze performance out of hardware because the software we use is riddled with surveillance and spyware.Almost all modern microprocessors employ tricks to squeeze more performance out of a computer program. A common trick involves having the microprocessor predict what the program is about to do and start doing it before it has been asked to do it — say, fetching data from memory. In a way, modern microprocessors act like attentive butlers, pouring that second glass of wine before you knew you were going to ask for it.

But what if you weren’t going to ask for that wine? What if you were going to switch to port? No problem: The butler just dumps the mistaken glass and gets the port. Yes, some time has been wasted. But in the long run, as long as the overall amount of time gained by anticipating your needs exceeds the time lost, all is well.

Except all is not well. Imagine that you don’t want others to know about the details of the wine cellar. It turns out that by watching your butler’s movements, other people can infer a lot about the cellar. Information is revealed that would not have been had the butler patiently waited for each of your commands, rather than anticipating them. Almost all modern microprocessors make these butler movements, with their revealing traces, and hackers can take advantage.

There have been patches going out over the past few weeks since the vulnerabilities came to light from major vendors. For-profit companies have limited resources, of course, and proprietary, closed-source code. This means there'll be some devices that won't get the security updates at all, leaving end users in a tricky situation: their hardware is now almost worthless. So do they (a) keep on using it, crossing their fingers that nothing bad happens, or (b) bite the bullet and upgrade?But the truth is that our computers are already quite fast. When they are slow for the end-user, it is often because of “bloatware”: badly written programs or advertising scripts that wreak havoc as they try to track your activity online. If we were to fix that problem, we would gain speed (and avoid threatening and needless surveillance of our behavior).

As things stand, we suffer through hack after hack, security failure after security failure. If commercial airplanes fell out of the sky regularly, we wouldn’t just shrug. We would invest in understanding flight dynamics, hold companies accountable that did not use established safety procedures, and dissect and learn from new incidents that caught us by surprise.

And indeed, with airplanes, we did all that. There is no reason we cannot do the same for safety and security of our digital systems.

What I think the communities I’m part of could have done better at is shout loudly that there’s an option (c): open source software. No matter how old your hardware, the chances are that someone, somewhere, with the requisite skills will want to fix the vulnerabilities on that device.

Source: The New York Times

The NSA (and GCHQ) can find you by your 'voiceprint' even if you're speaking a foreign language on a burner phone

This is pretty incredible:

Americans most regularly encounter this technology, known as speaker recognition, or speaker identification, when they wake up Amazon’s Alexa or call their bank. But a decade before voice commands like “Hello Siri” and “OK Google” became common household phrases, the NSA was using speaker recognition to monitor terrorists, politicians, drug lords, spies, and even agency employees.Hmmm….The technology works by analyzing the physical and behavioral features that make each person’s voice distinctive, such as the pitch, shape of the mouth, and length of the larynx. An algorithm then creates a dynamic computer model of the individual’s vocal characteristics. This is what’s popularly referred to as a “voiceprint.” The entire process — capturing a few spoken words, turning those words into a voiceprint, and comparing that representation to other “voiceprints” already stored in the database — can happen almost instantaneously. Although the NSA is known to rely on finger and face prints to identify targets, voiceprints, according to a 2008 agency document, are “where NSA reigns supreme.”

The voice is a unique and readily accessible biometric: Unlike DNA, it can be collected passively and from a great distance, without a subject’s knowledge or consent. Accuracy varies considerably depending on how closely the conditions of the collected voice match those of previous recordings. But in controlled settings — with low background noise, a familiar acoustic environment, and good signal quality — the technology can use a few spoken sentences to precisely match individuals. And the more samples of a given voice that are fed into the computer’s model, the stronger and more “mature” that model becomes.So yeah, let's put a microphone in every room of our house so that we can tell Alexa to turn off the lights. What could possibly go wrong?

Source: The Intercept

WTF is GDPR?

I have to say, I was quite dismissive of the impact of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) when I first heard about it. I thought it was going to be another debacle like the ‘this website uses cookies’ thing.

However, I have to say I’m impressed with what’s going to happen in May. It’s going to have a worldwide impact, too — as this article explains:

For an even shorter tl;dr the [European Commission's] theory is that consumer trust is essential to fostering growth in the digital economy. And it thinks trust can be won by giving users of digital services more information and greater control over how their data is used. Which is — frankly speaking — a pretty refreshing idea when you consider the clandestine data brokering that pervades the tech industry. Mass surveillance isn’t just something governments do.

It’s a big deal:

[GDPR is] set to apply across the 28-Member State bloc as of May 25, 2018. That means EU countries are busy transposing it into national law via their own legislative updates (such as the UK’s new Data Protection Bill — yes, despite the fact the country is currently in the process of (br)exiting the EU, the government has nonetheless committed to implementing the regulation because it needs to keep EU-UK data flowing freely in the post-brexit future. Which gives an early indication of the pulling power of GDPR....and unlike other regulations, actually has some teeth:

The maximum fine that organizations can be hit with for the most serious infringements of the regulation is 4% of their global annual turnover (or €20M, whichever is greater). Though data protection agencies will of course be able to impose smaller fines too. And, indeed, there’s a tiered system of fines — with a lower level of penalties of up to 2% of global turnover (or €10MI'm having conversations about it wherever I go, from my work at Moodle (an company headquartered in Australia) to the local Scouts.

Source: TechCrunch

Barely anyone uses 2FA

This is crazy.

In a presentation at Usenix's Enigma 2018 security conference in California, Google software engineer Grzegorz Milka today revealed that, right now, less than 10 per cent of active Google accounts use two-step authentication to lock down their services. He also said only about 12 per cent of Americans have a password manager to protect their accounts, according to a 2016 Pew study.Two-factor authentication (2FA), especially the kind where you use an app authenticator is so awesome you can use a much weaker password than normal, should you wish. (I, however, stick to the 16-digit one created by a deterministic password manager.)

Please, if you haven't already done so, just enable two-step authentication. This means when you or someone else tries to log into your account, they need not only your password but authorization from another device, such as your phone. So, simply stealing your password isn't enough – they need your unlocked phone, or similar, to to get in.I can't understand people who basically live their lives permanently one step away from being hacked. And for what? A very slightly more convenient life? Mad.

Source: The Register

Choose your connected silo

The Verge reports back from CES, the yearly gathering where people usually get excited about shiny thing. This year, however, people are bit more wary…

And it’s not just privacy and security that people need to think about. There’s also lock-in. You can’t just buy a connected gadget, you have to choose an ecosystem to live in. Does it work with HomeKit? Will it work with Alexa? Will some tech company get into a spat with another tech company and pull its services from that hardware thing you just bought?In other words, the kind of digital literacies required by the average consumer just went up a notch.

It won't be long before we'll be inviting techies around to debug our houses...Here’s the thing: it’s unlikely that the connected toothpaste will go back in the tube at this point. Consumer products will be more connected, not less. Some day not long from now, the average person’s stroll down the aisle at Target or Best Buy will be just like our experiences at futuristic trade shows: everything is connected, and not all of it makes sense.

Source: The Verge