- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion.

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job.

- Reduced professional efficacy.

- Your Kids Think You’re Addicted to Your Phone (The New York Times) — "Most parents worry that their kids are addicted to the devices, but about four in 10 teenagers have the same concern about their parents."

- Why the truth about our sugar intake isn't as bad as we are told (New Scientist) — "In fact, the UK government 'Family food datasets', which have detailed UK household food and drink expenditure since 1974, show there has been a 79 per cent decline in the use of sugar since 1974 – not just of table sugar, but also jams, syrups and honey."

- Can We Live Longer But Stay Younger? (The New Yorker) — "Where fifty years ago it was taken for granted that the problem of age was a problem of the inevitable running down of everything, entropy working its worst, now many researchers are inclined to think that the problem is “epigenetic”: it’s a problem in reading the information—the genetic code—in the cells."

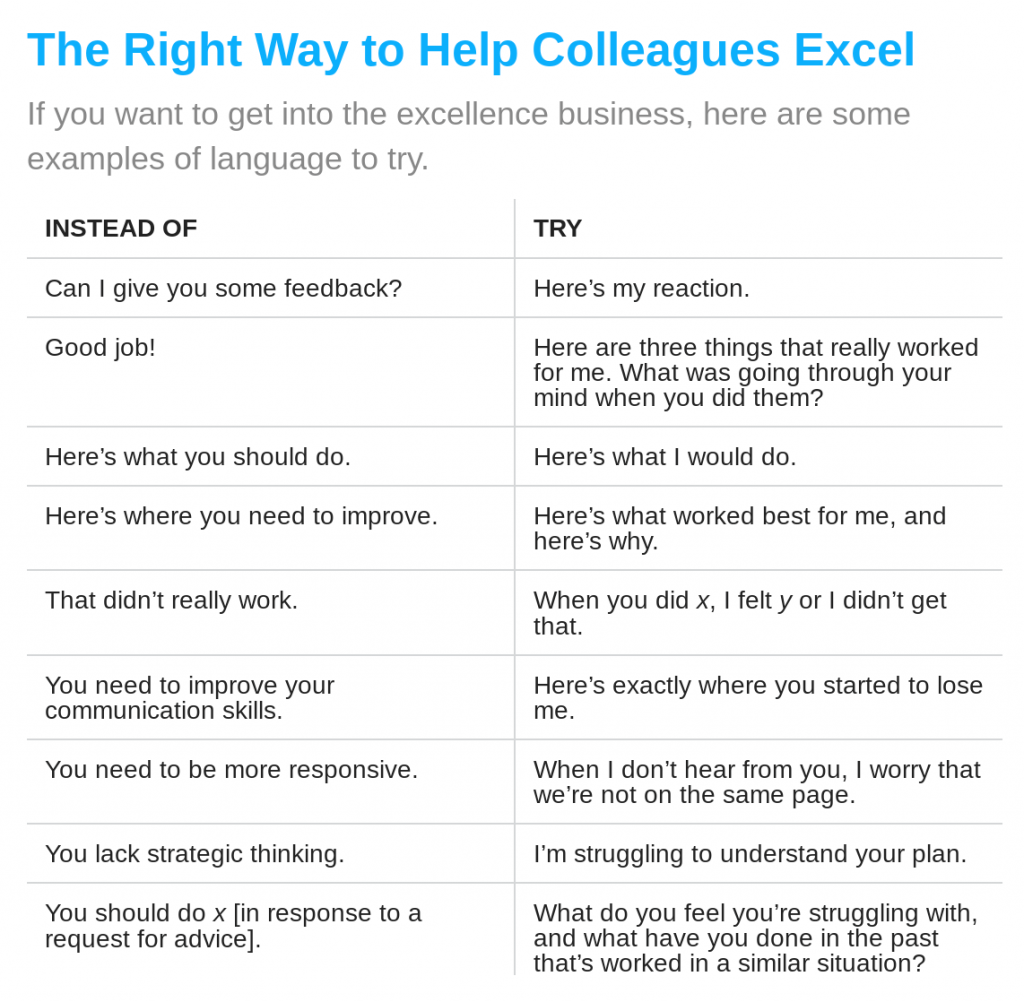

- Other people are more aware than you are of your weaknesses

- You lack certain abilities you need to acquire, so your colleagues should teach them to you

- Great performance is universal, analyzable, and describable, and that once defined, it can be transferred from one person to another, regardless of who each individual is

- Iris Murdoch, The Art of Fiction No. 117 (The Paris Review) — "I would abominate the idea of putting real people into a novel, not only because I think it’s morally questionable, but also because I think it would be terribly dull."

- How an 18th-Century Philosopher Helped Solve My Midlife Crisis (The Atlantic) — "I had found my salvation in the sheer endless curiosity of the human mind—and the sheer endless variety of human experience."

- A brief history of almost everything in five minutes (Aeon) —According to [the artist], the piece ‘is intended for both introspection and self-reflection, as a mirror to ourselves, our own mind and how we make sense of what we see; and also as a window into the mind of the machine, as it tries to make sense of its observations and memories’.

- Why Do You Grab Your Bag When Running Off a Burning Plane? (The New York Times) — it turns out that it's less of a decision, more of an impulse.

- If a house was designed by machine, how would it look? (BBC Business) — lighter, more efficient buildings.

- Playdate is an adorable handheld with games from the creators of Qwop, Katamari, and more (The Verge) — a handheld console with a hand crank that's actually used for gameplay instead of charging!

- The true story of the worst video game in history (Engadget) — it was so bad they buried millions of unsold cartridges in the desert.

- E Ink Smartphones are the big new trend of 2019 (Good e-Reader) — I've actually also own a regular phone with an e-ink display, so I can't wait for this to be a thing.

Inside your pain are the things you care about most deeply

I listened to this episode of The Art of Manliness podcast a while back on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and found it excellent. I've discussed ACT with my CBT therapist who says it can also be a useful approach.

My guest today says we need to free ourselves from these instincts and our default mental programming and learn to just sit with our thoughts, and even turn towards those which hurt the most. His name is Steven Hayes and he’s a professor of psychology, the founder of ACT — Acceptance and Commitment Therapy — and the author of over 40 books, including his latest 'A Liberated Mind: How to Pivot Toward What Matters'. Steven and I spend the first part of our conversation in a very interesting discussion as to why traditional interventions for depression and anxiety — drugs and talk therapy — aren’t very effective in helping people get their minds right, and how ACT takes a different approach to achieving mental health. We then discuss the six skills of psychological flexibility that undergird ACT and how these skills can be used not only by those dealing with depression and anxiety but by anyone who wants to get out of their own way and show up and move forward in every area of their lives.

Something that Hayes says is that "if people don't know what their values are, they take their goals, the concrete things they can achieve, to be their values". This, he says, is why rich people can still be unfulfilled.

Well worth a listen.

Rethinking human responses to adversity

As a parent and former teacher I can get behind this:

ADHD is not a disorder, the study authors argue. Rather it is an evolutionary mismatch to the modern learning environment we have constructed. Edward Hagen, professor of evolutionary anthropology at Washington State University and co-author of the study, pointed out in a press release that “there is little in our evolutionary history that accounts for children sitting at desks quietly while watching a teacher do math equations at a board.”

Alison Escalante, What If Certain Mental Disorders Are Not Disorders At All?, Psychology Today

This is a great article based on a journal article about PTSD, depression, anxiety, and ADHD. As someone who has suffered from depression in the past, and still deals with anxiety, I absolutely think it has an important situational aspect.

That is to say, instead of just medicating people, we need to be thinking about their context.

[T]he stated goal of the paper is not to suddenly change treatments, but to explore new ways of studying these problems. “Research on depression, anxiety, and PTSD, should put greater emphasis on mitigating conflict and adversity and less on manipulating brain chemistry.”

Alison Escalante, What If Certain Mental Disorders Are Not Disorders At All?, Psychology Today

Friday fashionings

When sitting down to put together this week's round-up, which is coming to you slightly later than usual because of <gestures indeterminately> all this, I decided that I'd only focus on things that are positive; things that might either raise a smile or make you think "oh, interesting!"

Let me know if I've succeeded in the comments below, via Twitter, Mastodon, or via email!

Digital Efficiency: the appeal of the minimalist home screen

The real advantage of going with a launcher like this instead of a more traditional one is simple: distraction reduction and productivity increases. Everything done while using this kind of setup is deliberate. There is no scrolling through pages upon pages of apps. There is no scrolling through Google Discover with story after story that you will probably never read. Instead between 3–7 app shortcuts are present, quick links to clock and calendar, and not much else. This setup requires you as the user to do an inventory of what apps you use the most. It really requires the user to rethink how they use their phone and what apps are the priority.

Omar Zahran (UX Collective)

A year ago, I wrote a post entitled Change your launcher, change your life about minimalist Android launchers. I'm now using the Before Launcher, because of the way you can easily and without any fuss customise notifications. Thanks to Ian O'Byrne for the heads-up in the We Are Open Slack channel.

It's Time for Shoulder Stretches

Cow face pose is the yoga name for that stretch where one hand reaches down your back, and the other hand reaches up. (There’s a corresponding thing you do with your legs, but forget it for now—we’re focusing on shoulders today.) If you can’t reach your hands together, it feels like a challenging or maybe impossible pose.

Lifehacker UK

I was pretty shocked that I couldn't barely do this with my right hand at the top and my left at the bottom. I was very shocked that I got nowhere near the other way around. It just goes to show that those people who work at home really need to work on back muscles and flexibility.

Dr. Seuss’s Fox in Socks Rapped Over Dr. Dre’s Beats

As someone who a) thinks Dr. Dre was an amazing producer, and b) read Dr. Seuss’s Fox in Socks to his children roughly 1 million times (enough to be able to, eventually, get through the entire book at a comically high rate of speed w/o any tongue twisting slip-ups), I thought Wes Tank’s video of himself rapping Fox in Socks over Dre’s beats was really fun and surprisingly well done.

Jason Kottke

One of the highlights of my kids being a bit younger than they are now was to read Dr. Suess to them. Fox in Socks was my absolute tongue-twisting favourite! So this blew me away, and then when I went through to YouTube, the algorithm recommended Daniel Radcliffe (the Harry Potter star) rapping Blackalicious' Alphabet Aerobics. Whoah.

Google launches free version of Stadia with a two-month Pro trial

Google is launching the free version of its Stadia game streaming service today. Anyone with a Gmail address can sign up, and Google is even providing a free two-month trial of Stadia Pro as part of the launch. It comes just two months after Google promised a free tier was imminent, and it will mean anyone can get access to nine titles, including GRID, Destiny 2: The Collection, and Thumper, free of charge.

Tom Warren (The Verge)

This is exactly the news I've been waiting for! Excellent.

Now is a great time to make some mediocre art

Practicing simple creative acts on a regular basis can give you a psychological boost, according to a 2016 study in the Journal of Positive Psychology. A 2010 review of more than 100 studies of art’s impact on health revealed that pursuits like music, writing, dance, painting, pottery, drawing, and photography improved medical outcomes, mental health, social networks, and positive identity. It was published in the American Journal of Public Health.

Gwen Moran (Fast Company)

I love all of the artists on Twitter and Instagram giving people daily challenges. My family have been following along with some of them!

What do we hear when we dream?

[R]esearchers at Norway's Vestre Viken Hospital Trust and the University of Bergen conducted a small study to quantify the auditory experience of dreamers. Why? Because they wanted to "assess the relevance of dreaming as a model for psychosis." Throughout history, they write, psychologists have considered dreamstates to be a model for psychosis, yet people experiencing psychosis usually suffer from auditory hallucinations far more than visual ones. Basically, what the researchers determined is that the reason so little is known about auditory sensations while dreaming is because, well, nobody asks what people's dreams sound like.

David Pescovitz (Boing boing)

This makes sense, if you think about it. The advice for doing online video is always that you get the audio right first. It would seem that it's the same for dreaming: that we pay attention more to what we 'hear' than what we 'see'.

How boredom can inspire adventure

Humans can’t stand being bored. Studies show we’ll do just about anything to avoid it, from compulsive smartphone scrolling right up to giving ourselves electric shocks. And as emotions go, boredom is incredibly good at parting us from our money – we’ll even try to buy our way out of the feeling with distractions like impulse shopping.

Erin Craig (BBC Travel)

The story in this article about a prisoner of war who dreamed up a daring escape is incredible, but does make the point that dreaming big when you're locked down is a grat idea.

But what could you learn instead?

“What did you learn today,” is a fine question to ask. Particularly right this minute, when we have more time and less peace of mind than is usually the norm.

It’s way easier to get someone to watch–a YouTube comic, a Netflix show, a movie–than it is to encourage them to do something. But it’s the doing that allows us to become our best selves, and it’s the doing that creates our future.

It turns out that learning isn’t in nearly as much demand as it could be. Our culture and our systems don’t push us to learn. They push us to conform and to consume instead.

The good news is that each of us, without permission from anyone else, can change that.

Seth Godin

A timely, inspirational post from the always readable (and listen-worthy) Seth Godin.

The Three Equations for a Happy Life, Even During a Pandemic

This column has been in the works for some time, but my hope is that launching it during the pandemic will help you leverage a contemplative mindset while you have the time to think about what matters most to you. I hope this column will enrich your life, and equip you to enrich the lives of the people you love and lead.

Arthur C. Brooks (The atlantic)

A really handy way of looking at things, and I'm hoping that further articles in the series are just as good.

Images by Kevin Burg and Jamie Beck (they're all over Giphy so I just went to the original source and used the hi-res versions)

Situations can be described but not given names

So said that most enigmatic of philosophers, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Today's article is about the effect of external stimulants on us as human beings, whether or not we can adequately name them.

Let's start with music, one of my favourite things in all the world. If the word 'passionate' hadn't been devalued from rampant overuse, I'd say that I'm passionate about music. One of the reasons is because it produces such a dramatic physiological response in me; my hairs stand on end and I get a surge of endophins — especially if I'm also running.

That's why Greg Evans' piece for The Independent makes me feel quite special. He reports on (admittedly small-scale) academic research which shows that some people really do feel music differently to others:

Matthew Sachs a former undergraduate at Harvard, last year studied individuals who get chills from music to see how this feeling was triggered.

The research examined 20 students, 10 of which admitted to experiencing the aforementioned feelings in relation to music and 10 that didn't and took brain scans of all of them all.

He discovered that those that had managed to make the emotional and physical attachment to music actually have different brain structures than those that don't.

The research showed that they tended to have a denser volume of fibres that connect their auditory cortex and areas that process emotions, meaning the two can communicate better.

Greg Evans

This totally makes sense to me. I'm extremely emotionally invested in almost everything I do, especially my work. For example, I find it almost unbearably difficult to work on something that I don't agree with or think is important.

The trouble with this, of course, and for people like me, is that unless we're careful we're much more likely to become 'burned out' by our work. Nate Swanner reports for Dice that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has recently recognised burnout as a legitimate medical syndrome:

The actual definition is difficult to pin down, but the WHO defines burnout by these three markers:

Interestingly enough, the actual description of burnout asks that all three of the above criteria be met. You can’t be really happy and not producing at work; that’s not burnout.

As the article suggests, now burnout is a recognised medical term, we now face the prospect of employers being liable for causing an environment that causes burnout in their employees. It will no longer, hopefully, be a badge of honour to have burned yourself out for the sake of a venture capital-backed startup.

Having experienced burnout in my twenties, the road to recovery can take a while, and it has an effect on the people around you. You have to replace negative thoughts and habits with new ones. I ultimately ended up moving both house and sectors to get over it.

As Jason Fried notes on Signal v. Noise, we humans always form habits:

When we talk about habits, we generally talk about learning good habits. Or forming good habits. Both of these outcomes suggest we can end up with the habits we want. And technically we can! But most of the habits we have are habits we ended up with after years of unconscious behavior. They’re not intentional. They’ve been planting deep roots under the surface, sight unseen. Fertilized, watered, and well-fed by recurring behavior. Trying to pull that habit out of the ground later is going to be incredibly difficult. Your grip has to be better than its grip, and it rarely is.

Jason Fried

This is a great analogy. It's easy for weeds to grow in the garden of our mind. If we're not careful, as Fried points out, these can be extremely difficult to get rid of once established. That's why, as I've discussed before, tracking one's habits is itself a good habit to get into.

Over a decade ago, a couple of years after suffering from burnout, I wrote a post outlining what I rather grandly called The Vortex of Uncompetence. Let's just say that, if you recognise yourself in any of what I write in that post, it's time to get out. And quickly.

Also check out:

We never look at just one thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves

Today's title comes from John Berger's Ways of Seeing, which is an incredible book. Soon after the above quotation, he continues,

The eye of the other combines with our own eye to make it fully credible that we are part of the visible world.

John Berger

That period of time when you come to be you is really interesting. As an adolescent, and before films like The Matrix, I can remember thinking that the world literally revolved around me; that other people were testing me in some way. I hope that's kind of normal, and I'd add somewhat hastily that I grew out of that way of thinking a long time ago. Obviously.

All of this is a roundabout way of saying that we cannot know the 'inner lives' of other people, or in fact that they have them. Writing in The Guardian, psychologist Oliver Burkeman notes that we sail through life assuming that we experience everything similarly, when that's not true at all:

A new study on a technical-sounding topic – “genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire” – is a reminder that we smell the world differently... Researchers found that a single genetic mutation accounts for many of those differences: the way beetroot smells (and tastes) like disgustingly dirty soil to some people, or how others can’t detect the smokiness of whisky, or smell lily of the valley in perfumes.

Oliver Burkeman

I know that my wife sees colours differently to me, as purple is one of her favourite colours. Neither of us is colour-blind, but some things she calls 'purple' are in no way 'purple' to me.

So when it comes to giving one another feedback, where should we even begin? How can we know the intentions or the thought processes behind someone's actions? In an article for Harvard Business Review, Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall explain that our theories about feedback are based on three theories:

All of these, the author's claim, are false:

What the research has revealed is that we’re all color-blind when it comes to abstract attributes, such as strategic thinking, potential, and political savvy. Our inability to rate others on them is predictable and explainable—it is systematic. We cannot remove the error by adding more data inputs and averaging them out, and doing that actually makes the error bigger.

Buckingham & Goodall

What I liked was their actionable advice about how to help colleagues thrive, captured in this table:

Finally, as an educator and parent, I've noticed that human learning doesn't follow a linear trajectory. Anything but, in fact. Yet we talk and interact as though it does. That's why I found Good Things By Their Nature Are Fragile by Jason Kottke so interesting, quoting a 2005 post from Michael Barrish. I'm going to quote the same section as Kottke:

In 1988 Laura and I created a three-stage model of what we called “living process.” We called the three stages Good Thing, Rut, and Transition. As we saw it, Good Thing becomes Rut, Rut becomes Transition, and Transition becomes Good Thing. It’s a continuous circuit.

A Good Thing never leads directly to a Transition, in large part because it has no reason to. A Good Thing wants to remain a Good Thing, and this is precisely why it becomes a Rut. Ruts, on the other hand, want desperately to change into something else.

Transitions can be indistinguishable from Ruts. The only important difference is that new events can occur during Transitions, whereas Ruts, by definition, consist of the same thing happening over and over.

Michael Barrish

In life, sometimes we don't even know what stage we're in, never mind other people. So let's cut one another some slack, dispel the three myths about feedback listed above, and allow people to be different to us in diverse and glorious ways.

Also check out:

Header image: webcomicname.com

Friday fumblings

These were the things I came across this week that made me smile:

Image via Why WhatsApp Will Never Be Secure (Pavel Durov)

What do happy teenagers do?

This chart, via Psychology Today, is pretty unequivocal. It shows the activities correlated with happiness (green) and unhappiness (red) in American teenagers:

I discussed this with our eleven year-old son, who pretty much just nodded his head. I’m not sure he knew what to say, given that most of the things he enjoys doing in his free time are red on that chart!

Take a look at the bottom of the chart: Listening to music shows the strongest correlation with unhappiness. That may seem strange at first, but consider how most teens listen to music these days: On their phones, with earbuds firmly in place. Although listening to music is not screen time per se, it is a phone activity for the vast majority of teens. Teens who spend hours listening to music are often shutting out the world, effectively isolating themselves in a cocoon of sound.This stuff isn't rocket science, I guess:

There’s another way to look at this chart – with the exception of sleep, activities that usually involve being with other people are the most strongly correlated with happiness, and those that involve being alone are the most strongly correlated with unhappiness. That might be why listening to music, which most teens do alone, is linked to unhappiness, while going to music concerts, which is done with other people, is linked to happiness. It’s not the music that’s linked to unhappiness; it’s the way it’s enjoyed. There are a few gray areas here. Talking on a cell phone and using video chat are linked to less happiness – perhaps because talking on the phone, although social connection, is not as satisfying as actually being with others, or because they are a phone activities even though they are not, strictly speaking, screen time. Working, usually done with others, is a wash, perhaps because most of the jobs teens have are not particularly fulfilling.I might pin this up in the house somewhere for future reference...

Source: Psychology Today

Childhood amnesia

My kids will often ask me about what I was like at their age. It might be about how fast I swam a couple of length freestyle, it could be what music I was into, or when I went on a particular holiday I mentioned in passing. Of course, as I didn’t keep a diary as a child, these questions are almost impossible to answer. I simply can’t remember how old I was when certain things happened.

Over and above that, though, there’s some things that I’ve just completely forgotten. I only realise this when I see, hear, or perhaps smell something that reminds me of a thing that my conscious mind had chosen to leave behind. It’s particularly true of experiences from when we are very young. This phenomenon is known as ‘childhood amnesia’, as an article in Nautilus explains:

On average, people’s memories stretch no farther than age three and a half. Everything before then is a dark abyss. “This is a phenomenon of longstanding focus,” says Patricia Bauer of Emory University, a leading expert on memory development. “It demands our attention because it’s a paradox: Very young children show evidence of memory for events in their lives, yet as adults we have relatively few of these memories.”Interestingly, our seven year-old daughter is on the cusp of this forgetting. She’s slowly forgetting things that she had no problem recalling even last year, and has to be prompted by photographs of the event or experience.In the last few years, scientists have finally started to unravel precisely what is happening in the brain around the time that we forsake recollection of our earliest years. “What we are adding to the story now is the biological basis,” says Paul Frankland, a neuroscientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. This new science suggests that as a necessary part of the passage into adulthood, the brain must let go of much of our childhood.

One experiment after another revealed that the memories of children 3 and younger do in fact persist, albeit with limitations. At 6 months of age, infants’ memories last for at least a day; at 9 months, for a month; by age 2, for a year. And in a landmark 1991 study, researchers discovered that four-and-a-half-year-olds could recall detailed memories from a trip to Disney World 18 months prior. Around age 6, however, children begin to forget many of these earliest memories. In a 2005 experiment by Bauer and her colleagues, five-and-a-half-year-olds remembered more than 80 percent of experiences they had at age 3, whereas seven-and-a-half-year-olds remembered less than 40 percent.It's fascinating, and also true of later experiences, although to a lesser extent. Our brains conceal some of our memories by rewiring our brain. This is all part of growing up.

This restructuring of memory circuits means that, while some of our childhood memories are truly gone, others persist in a scrambled, refracted way. Studies have shown that people can retrieve at least some childhood memories by responding to specific prompts—dredging up the earliest recollection associated with the word “milk,” for example—or by imagining a house, school, or specific location tied to a certain age and allowing the relevant memories to bubble up on their own.So we shouldn't worry too much about remembering childhood experiences in high-fidelity. After all, it's important to be able to tell new stories to both ourselves and other people, casting prior experiences in a new light.

Source: Nautilus

Childhood amnesia

My kids will often ask me about what I was like at their age. It might be about how fast I swam a couple of length freestyle, it could be what music I was into, or when I went on a particular holiday I mentioned in passing. Of course, as I didn’t keep a diary as a child, these questions are almost impossible to answer. I simply can’t remember how old I was when certain things happened.

Over and above that, though, there’s some things that I’ve just completely forgotten. I only realise this when I see, hear, or perhaps smell something that reminds me of a thing that my conscious mind had chosen to leave behind. It’s particularly true of experiences from when we are very young. This phenomenon is known as ‘childhood amnesia’, as an article in Nautilus explains:

On average, people’s memories stretch no farther than age three and a half. Everything before then is a dark abyss. “This is a phenomenon of longstanding focus,” says Patricia Bauer of Emory University, a leading expert on memory development. “It demands our attention because it’s a paradox: Very young children show evidence of memory for events in their lives, yet as adults we have relatively few of these memories.”Interestingly, our seven year-old daughter is on the cusp of this forgetting. She’s slowly forgetting things that she had no problem recalling even last year, and has to be prompted by photographs of the event or experience.In the last few years, scientists have finally started to unravel precisely what is happening in the brain around the time that we forsake recollection of our earliest years. “What we are adding to the story now is the biological basis,” says Paul Frankland, a neuroscientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. This new science suggests that as a necessary part of the passage into adulthood, the brain must let go of much of our childhood.

One experiment after another revealed that the memories of children 3 and younger do in fact persist, albeit with limitations. At 6 months of age, infants’ memories last for at least a day; at 9 months, for a month; by age 2, for a year. And in a landmark 1991 study, researchers discovered that four-and-a-half-year-olds could recall detailed memories from a trip to Disney World 18 months prior. Around age 6, however, children begin to forget many of these earliest memories. In a 2005 experiment by Bauer and her colleagues, five-and-a-half-year-olds remembered more than 80 percent of experiences they had at age 3, whereas seven-and-a-half-year-olds remembered less than 40 percent.It's fascinating, and also true of later experiences, although to a lesser extent. Our brains conceal some of our memories by rewiring our brain. This is all part of growing up.

This restructuring of memory circuits means that, while some of our childhood memories are truly gone, others persist in a scrambled, refracted way. Studies have shown that people can retrieve at least some childhood memories by responding to specific prompts—dredging up the earliest recollection associated with the word “milk,” for example—or by imagining a house, school, or specific location tied to a certain age and allowing the relevant memories to bubble up on their own.So we shouldn't worry too much about remembering childhood experiences in high-fidelity. After all, it's important to be able to tell new stories to both ourselves and other people, casting prior experiences in a new light.

Source: Nautilus

The 'loudness' of our thoughts affects how we judge external sounds

This is really interesting:

No-one but you knows what it's like to be inside your head and be subject to the constant barrage of hopes, fears, dreams — and thoughts:The "loudness" of our thoughts -- or how we imagine saying something -- influences how we judge the loudness of real, external sounds, a team of researchers from NYU Shanghai and NYU has found.

"Our 'thoughts' are silent to others -- but not to ourselves, in our own heads -- so the loudness in our thoughts influences the loudness of what we hear," says Poeppel, a professor of psychology and neural science.This is why meditation, both in terms of trying to still your mind, and meditating on positive things you read, is such a useful activity.Using an imagery-perception repetition paradigm, the team found that auditory imagery will decrease the sensitivity of actual loudness perception, with support from both behavioural loudness ratings and human electrophysiological (EEG and MEG) results.

“That is, after imagined speaking in your mind, the actual sounds you hear will become softer – the louder the volume during imagery, the softer perception will be,” explains Tian, assistant professor of neural and cognitive sciences at NYU Shanghai. “This is because imagery and perception activate the same auditory brain areas. The preceding imagery already activates the auditory areas once, and when the same brain regions are needed for perception, they are ‘tired’ and will respond less."

As anyone who’s studied philosophy, psychology, and/or neuroscience knows, we don’t experience the world directly, but find ways to interpret the “bloomin' buzzin' confusion”:

According to Tian, the study demonstrates that perception is a result of interaction between top-down (e.g. our cognition) and bottom-up (e.g. sensory processing of external stimulation) processes. This is because human beings not only receive and analyze upcoming external signals passively, but also interpret and manipulate them actively to form perception.Source: Science Daily

The Goldilocks Rule

In this article from 2016, James Clear investigates motivation:

Why do we stay motivated to reach some goals, but not others? Why do we say we want something, but give up on it after a few days? What is the difference between the areas where we naturally stay motivated and those where we give up?The answer, which is obvious when we think about it, is that we need appropriate challenges in our lives:

Tasks that are significantly below your current abilities are boring. Tasks that are significantly beyond your current abilities are discouraging. But tasks that are right on the border of success and failure are incredibly motivating to our human brains. We want nothing more than to master a skill just beyond our current horizon.But he doesn’t stop there. He goes on to talk about Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s notion of peak performance, or ‘flow’ states:We can call this phenomenonThe Goldilocks Rule. The Goldilocks Rule states that humans experience peak motivation when working on tasks that are right on the edge of their current abilities. Not too hard. Not too easy. Just right.

In order to reach this state of peak performance... you not only need to work on challenges at the right degree of difficulty, but also measure your immediate progress. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt explains, one of the keys to reaching a flow state is that “you get immediate feedback about how you are doing at each step.”Video games are great at inducing flow states; traditional classroom-based learning experiences, not so much. The key is to create these experiences yourself by finding optimum challenge and immediate feedback.

Source: Lifehacker

Your brain is not a computer

I finally got around to reading this article after it was shared in so many places I frequent over the last couple of days. As someone who has studied Philosophy, History, and Education, I find it well-written but unremarkable. Surely we all know this… right?

Misleading headlines notwithstanding, no one really has the slightest idea how the brain changes after we have learned to sing a song or recite a poem. But neither the song nor the poem has been ‘stored’ in it. The brain has simply changed in an orderly way that now allows us to sing the song or recite the poem under certain conditions. When called on to perform, neither the song nor the poem is in any sense ‘retrieved’ from anywhere in the brain, any more than my finger movements are ‘retrieved’ when I tap my finger on my desk. We simply sing or recite – no retrieval necessary.Source: Aeon