- People seem not to see that their opinion of the world is also a confession of character

- We have it in our power to begin the world over again

- There is no creature whose inward being is so strong that it is not greatly determined by what lies outside it

- The old is dying and the new cannot be born

- Awesome Screenshot

- ColorZilla

- Containers Sync

- Dark Reader

- Decentraleyes

- Disconnect

- DownloadThemAll!

- Firefox Multi-Account Containers

- Floccus

- Fraidycat

- LessPass

- Livemarks

- Momentum

- NoPlugin

- Plasma integration

- Privacy Badger

- RSSPreview

- Terms of Service; Didn't Read

- The Camelizer

- uBlock Origin

- Video DownloadHelper

- Web Developer

- Zoom Scheduler

- Overrated: Ludwig Wittgenstein (Standpoint) — "Wittgenstein’s reputation for genius did not depend on incomprehensibility alone. He was also “tortured”, rude and unreliable. He had an intense gaze. He spent months in cold places like Norway to isolate himself. He temporarily quit philosophy, because he believed that he had solved all its problems in his 1922 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, and worked as a gardener. He gave away his family fortune. And, of course, he was Austrian, as so many of the best geniuses are."

- EdTech Resistance (Ben Williamson) — "We should not and cannot ignore these tensions and challenges. They are early signals of resistance ahead for edtech which need to be engaged with before they turn to public outrage. By paying attention to and acting on edtech resistances it may be possible to create education systems, curricula and practices that are fair and trustworthy. It is important not to allow edtech resistance to metamorphose into resistance to education itself."

- The Guardian view on machine learning: a computer cleverer than you? (The Guardian) — "The promise of AI is that it will imbue machines with the ability to spot patterns from data, and make decisions faster and better than humans do. What happens if they make worse decisions faster? Governments need to pause and take stock of the societal repercussions of allowing machines over a few decades to replicate human skills that have been evolving for millions of years."

- A nerdocratic oath (Scott Aaronson) — "I will never allow anyone else to make me a cog. I will never do what is stupid or horrible because “that’s what the regulations say” or “that’s what my supervisor said,” and then sleep soundly at night. I’ll never do my part for a project unless I’m satisfied that the project’s broader goals are, at worst, morally neutral. There’s no one on earth who gets to say: “I just solve technical problems. Moral implications are outside my scope”."

- Privacy is power (Aeon) — "The power that comes about as a result of knowing personal details about someone is a very particular kind of power. Like economic power and political power, privacy power is a distinct type of power, but it also allows those who hold it the possibility of transforming it into economic, political and other kinds of power. Power over others’ privacy is the quintessential kind of power in the digital age."

- The Symmetry and Chaos of the World's Megacities (WIRED) — "Koopmans manages to create fresh-looking images by finding unique vantage points, often by scouting his locations on Google Earth. As a rule, he tries to get as high as he can—one of his favorite tricks is talking local work crews into letting him shoot from the cockpit of a construction crane."

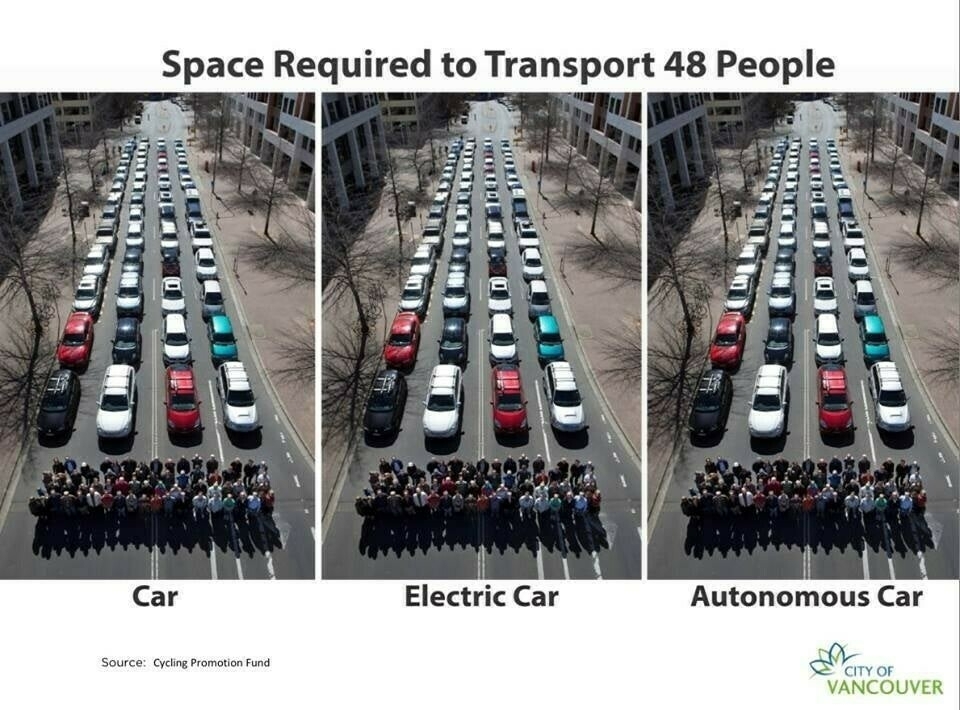

- Green cities of the future - what we can expect in 2050 (RNZ) — "In their lush vision of the future, a hyperloop monorail races past in the foreground and greenery drapes the sides of skyscrapers that house communal gardens and vertical farms."

- Wittgenstein Teaches Elementary School (Existential Comics) — "And I'll have you all know, there is no crying in predicate logic."

- Ask Yourself These 5 Questions to Inspire a More Meaningful Career Move (Inc.) — "Introspection on the right things can lead to the life you want."

- Study shows some political beliefs are just historical accidents (Ars Technica) — "Obviously, these experiments aren’t exactly like the real world, where political leaders can try to steer their parties. Still, it’s another way to show that some political beliefs aren’t inviolable principles—some are likely just the result of a historical accident reinforced by a potent form of tribal peer pressure. And in the early days of an issue, people are particularly susceptible to tribal cues as they form an opinion."

- Please, My Digital Archive. It’s Very Sick. (Lapham's Quarterly) — "An archivist’s dream is immaculate preservation, documentation, accessibility, the chance for our shared history to speak to us once more in the present. But if the preservation of digital documents remains an unsolvable puzzle, ornery in ways that print materials often aren’t, what good will our archiving do should it become impossible to inhabit the world we attempt to preserve?"

- So You’re 35 and All Your Friends Have Already Shed Their Human Skins (McSweeney's) — "It’s a myth that once you hit 40 you can’t slowly and agonizingly mutate from a human being into a hideous, infernal arachnid whose gluttonous shrieks are hymns to the mad vampire-goddess Maggorthulax. You have time. There’s no biological clock ticking. The parasitic worms inside you exist outside of our space-time continuum."

- Investing in Your Ordinary Powers (Breaking Smart) — "The industrial world is set up to both encourage and coerce you to discover, as early as possible, what makes you special, double down on it, and build a distinguishable identity around it. Your specialness-based identity is in some ways your Industrial True Name. It is how the world picks you out from the crowd."

- Browser Fingerprinting: An Introduction and the Challenges Ahead (The Tor Project) — "This technique is so rooted in mechanisms that exist since the beginning of the web that it is very complex to get rid of it. It is one thing to remove differences between users as much as possible. It is a completely different one to remove device-specific information altogether."

- What is a Blockchain Phone? The HTC Exodus explained (giffgaff) — "HTC believes that in the future, your phone could hold your passport, driving license, wallet, and other important documents. It will only be unlockable by you which makes it more secure than paper documents."

- Debate rages in Austria over enshrining use of cash in the constitution (EURACTIV) — "Academic and author Erich Kirchler, a specialist in economic psychology, says in Austria and Germany, citizens are aware of the dangers of an overmighty state from their World War II experience."

- Cory Doctorow: DRM Broke Its Promise (Locus magazine) — "We gave up on owning things – property now being the exclusive purview of transhuman immortal colony organisms called corporations – and we were promised flexibility and bargains. We got price-gouging and brittleness."

- Five Books That Changed Me In One Summer (Warren Ellis) — "I must have been around 14. Rayleigh Library and the Oxfam shop a few doors down the high street from it, which someone was clearly using to pay things forward and warp younger minds."

- Apple created the privacy dystopia it wants to save you from (Fast Company) — I'm not sure I agree with either the title or subtitle of this piece, but it raises some important points.

- When Grown-Ups Get Caught in Teens’ AirDrop Crossfire (The Atlantic) — hilarious and informative in equal measure!

- Anxiety, revolution, kidnapping: therapy secrets from across the world (The Guardian) — a fascinating look at the reasons why people in different countries get therapy.

- Post-it note war over flowers deemed ‘most middle-class argument ever’ (Metro) — amusing, but there's important things to learn from this about private/public spaces.

- Modern shamans: Financial managers, political pundits and others who help tame life’s uncertainty (The Conversation) — a 'cognitive anthropologist' explains the role of shamans in ancient societies, and extends the notion to the modern world.

- A New York School District Will Test Facial Recognition System On Students Even Though The State Asked It To Wait (BuzzFeed News) — "Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has expressed concern in a congressional hearing on the technology last week that facial recognition could be used as a form of social control."

- Amazon preparing a wearable that ‘reads human emotions,’ says report (The Verge) — "This is definitely one of those things that hasn’t yet been done because of how hard it is to do."

- Google’s Sundar Pichai: Privacy Should Not Be a Luxury Good (The New York Times) — "Ideally, privacy legislation would require all businesses to accept responsibility for the impact of their data processing in a way that creates consistent and universal protections for individuals and society as a whole.

- Do nothing and allow the trolley to kill the five people on the main track.

- Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.

- Human agency and oversight: AI systems should enable equitable societies by supporting human agency and fundamental rights, and not decrease, limit or misguide human autonomy.

- Robustness and safety: Trustworthy AI requires algorithms to be secure, reliable and robust enough to deal with errors or inconsistencies during all life cycle phases of AI systems.

- Privacy and data governance: Citizens should have full control over their own data, while data concerning them will not be used to harm or discriminate against them.

- Transparency: The traceability of AI systems should be ensured.

- Diversity, non-discrimination and fairness: AI systems should consider the whole range of human abilities, skills and requirements, and ensure accessibility.

- Societal and environmental well-being: AI systems should be used to enhance positive social change and enhance sustainability and ecological responsibility.

- Accountability: Mechanisms should be put in place to ensure responsibility and accountability for AI systems and their outcomes.

- How to hack your face to dodge the rise of facial recognition tech (WIRED) — "The real solution to the issues around FR? The tech community working with other industries and sectors to strike an appropriate balance between security and privacy in public spaces."

- U.S., U.K. embrace autonomous robot spy subs that can stay at sea for months (Digital Trends) — "According to a department spokesperson, these autonomous subs will most likely not carry weapons, although a final decision has not been made."

- The world’s first genderless AI voice is here. Listen now (Fast Company) — "In other words, because Siri cannot be gender neutral, she reinforces a dated tradition of gender norms."

If you have been put in your place long enough, you begin to act like the place

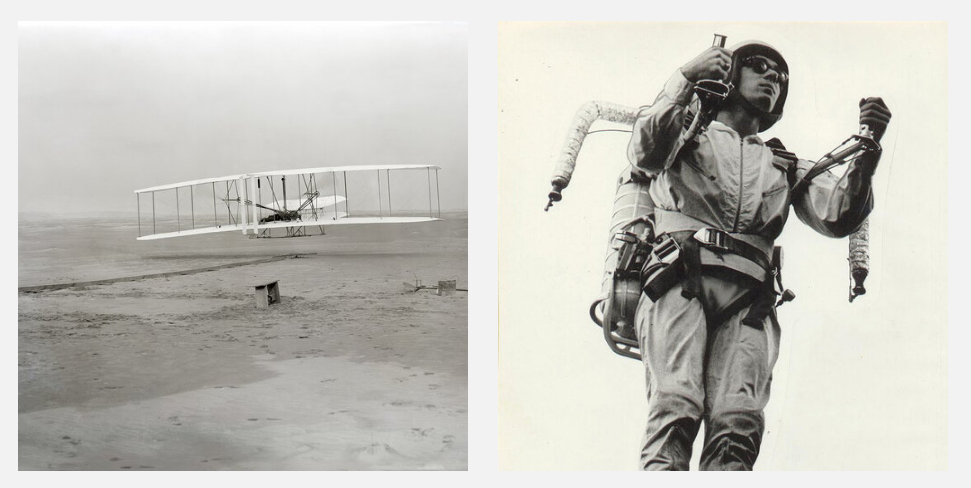

📉 Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit

💪 How to walk upright and stop living in a cave

🤔 It’s Not About Intention, It’s About Action

💭 Are we losing our ability to remember?

🇺🇸 How The Presidential Candidates Spy On Their Supporters

Quotation-as-title by Randall Jarrell. Image from top-linked post.

Seeing through is rarely seeing into

♂️ What does it mean to be a man in 2020? Introducing our news series on masculinity

✏️ Your writing style is costly (Or, a case for using punctuation in Slack)

Quotation-as-title by Elizabeth Bransco. Image from top-linked post.

At times, our strengths propel us so far forward we can no longer endure our weaknesses and perish from them

🤑 We can’t have billionaires and stop climate change

📹 How to make video calls almost as good as face-to-face

⏱️ How to encourage your team to launch an MVP first

☑️ Now you can enforce your privacy rights with a single browser tick

Quotation-as-title from Nietzsche. Image from top-linked post.

Saturday shakings

Whew, so many useful bookmarks to re-read for this week’s roundup! It took me a while, so let’s get on with it…

What is the future of distributed work?

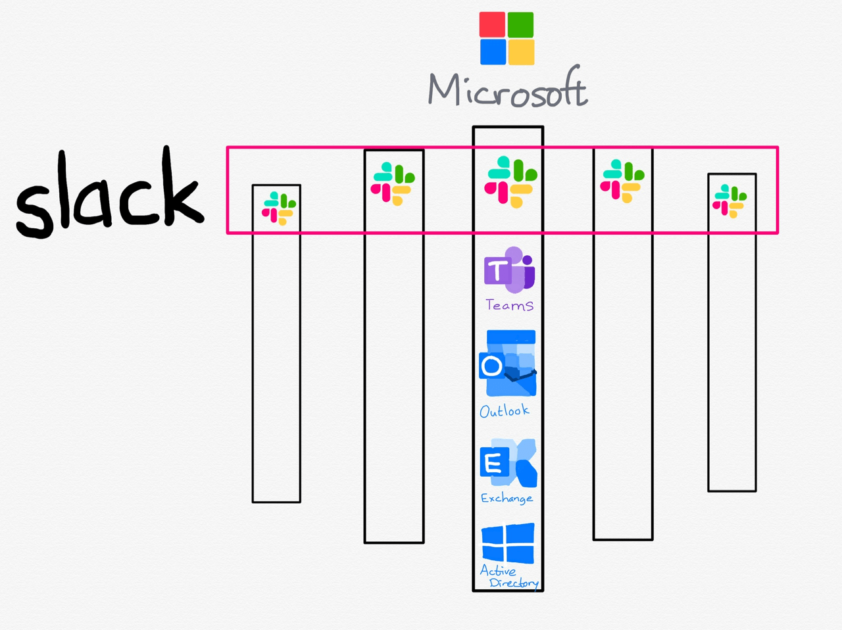

To Bharat Mediratta, chief technology officer at Dropbox, the quarantine experience has highlighted a huge gap in the market. “What we have right now is a bunch of different productivity and collaboration tools that are stitched together. So I will do my product design in Figma, and then I will submit the code change on GitHub, I will push the product out live on AWS, and then I will communicate with my team using Gmail and Slack and Zoom,” he says. “We have all that technology now, but we don't yet have the ‘digital knowledge worker operating system’ to bring it all together.”

WIRED

OK, so this is a sponsored post by Dropbox on the WIRED website, but what it highlights is interesting. For example, Monday.com (which our co-op uses) rebranded itself a few months ago as a 'Work OS'. There's definitely a lot of money to be made for whoever manages to build an integrated solution, although I think we're a long way off something which is flexible enough for every use case.

The Definition of Success Is Autonomy

Today, I don’t define success the way that I did when I was younger. I don’t measure it in copies sold or dollars earned. I measure it in what my days look like and the quality of my creative expression: Do I have time to write? Can I say what I think? Do I direct my schedule or does my schedule direct me? Is my life enjoyable or is it a chore?

Ryan Holiday

Tim Ferriss has this question he asks podcast guests: "If you could have a gigantic billboard anywhere with anything on it what would it say and why?" I feel like the title of this blog post is one of the answers I would give to that question.

Do The Work

We are a small group of volunteers who met as members of the Higher Ed Learning Collective. We were inspired by the initial demand, and the idea of self-study, interracial groups. The initial decision to form this initiative is based on the myriad calls from people of color for white-bodied people to do internal work. To do the work, we are developing a space for all individuals to read, share, discuss, and interrogate perspectives on race, racism, anti-racism, identity in an educational setting. To ensure that the fight continues for justice, we need to participate in our own ongoing reflection of self and biases. We need to examine ourselves, ask questions, and learn to examine our own perspectives. We need to get uncomfortable in asking ourselves tough questions, with an understanding that this is a lifelong, ongoing process of learning.

Ian O'Byrne

This is a fantastic resource for people who, like me, are going on a learning journey at the moment. I've found the podcast Seeing White by Scene on Radio particularly enlightening, and at times mind-blowing. Also, the Netflix documentary 13th is excellent, and available on YouTube.

How to Make Your Tech Last Longer

If we put a small amount of time into caring for our gadgets, they can last indefinitely. We’d also be doing the world a favor. By elongating the life of our gadgets, we put more use into the energy, materials and human labor invested in creating the product.

Brian X. Chen (The new York times)

This is a pretty surface-level article that basically suggests people take their smartphone to a repair shop instead of buying a new one. What it doesn't mention is that aftermarket operating systems such as the Android-based LineageOS can extend the lifetime of smartphones by providing security updates long beyond those provided by vendors.

Law enforcement arrests hundreds after compromising encrypted chat system

EncroChat sold customized Android handsets with GPS, camera, and microphone functionality removed. They were loaded with encrypted messaging apps as well as a secure secondary operating system (in addition to Android). The phones also came with a self-destruct feature that wiped the device if you entered a PIN.

The service had customers in 140 countries. While it was billed as a legitimate platform, anonymous sources told Motherboard that it was widely used among criminal groups, including drug trafficking organizations, cartels, and gangs, as well as hitmen and assassins.

EncroChat didn’t become aware that its devices had been breached until May after some users noticed that the wipe function wasn’t working. After trying and failing to restore the features and monitor the malware, EncroChat cut its SIM service and shut down the network, advising customers to dispose of their devices.

Monica Chin (The Verge)

It goes without saying that I don't want assassins, drug traffickers, and mafia types to be successful in life. However, I'm always a little concerned when there are attacks on encryption, as they're compromising systems also potentially used by protesters, activists, and those who oppose the status quo.

Uncovered: 1,000 phrases that incorrectly trigger Alexa, Siri, and Google Assistant

The findings demonstrate how common it is for dialog in TV shows and other sources to produce false triggers that cause the devices to turn on, sometimes sending nearby sounds to Amazon, Apple, Google, or other manufacturers. In all, researchers uncovered more than 1,000 word sequences—including those from Game of Thrones, Modern Family, House of Cards, and news broadcasts—that incorrectly trigger the devices.

“The devices are intentionally programmed in a somewhat forgiving manner, because they are supposed to be able to understand their humans,” one of the researchers, Dorothea Kolossa, said. “Therefore, they are more likely to start up once too often rather than not at all.”

Dan Goodin (Ars Technica)

As anyone with voice assistant-enabled devices in their home will testify, the number of times they accidentally spin up, or misunderstand what you're saying can be amusing. But we can and should be wary of what's being listened to, and why.

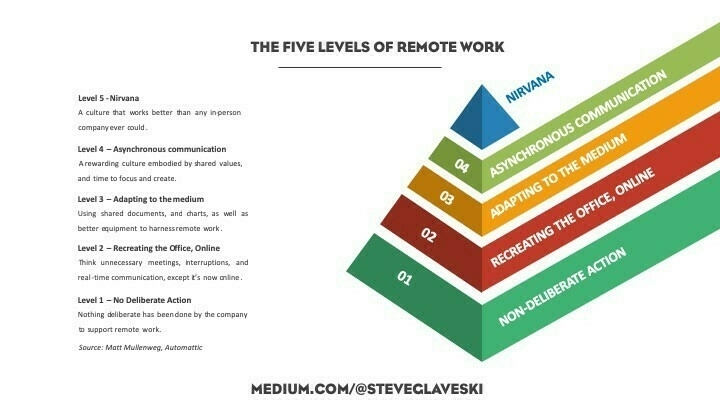

The Five Levels of Remote Work — and why you’re probably at Level 2

Effective written communication becomes critical the more companies embrace remote work. With an aversion to ‘jumping on calls’ at a whim, and a preference for asynchronous communication... [most] communications [are] text-based, and so articulate and timely articulation becomes key.

Steve Glaveski (The Startup)

This is from March and pretty clickbait-y, but everyone wants to know how they can improve - especially if didn't work remotely before the pandemic. My experience is that actually most people are at Level 3 and, of course, I'd say that I and my co-op colleagues are at Level 5 given our experience...

Why Birds Can Fly Over Mount Everest

All mammals, including us, breathe in through the same opening that we breathe out. Can you imagine if our digestive system worked the same way? What if the food we put in our mouths, after digestion, came out the same way? It doesn’t bear thinking about! Luckily, for digestion, we have a separate in and out. And that’s what the birds have with their lungs: an in point and an out point. They also have air sacs and hollow spaces in their bones. When they breathe in, half of the good air (with oxygen) goes into these hollow spaces, and the other half goes into their lungs through the rear entrance. When they breathe out, the good air that has been stored in the hollow places now also goes into their lungs through that rear entrance, and the bad air (carbon dioxide and water vapor) is pushed out the front exit. So it doesn’t matter whether birds are breathing in or out: Good air is always going in one direction through their lungs, pushing all the bad air out ahead of it.

Walter Murch (Nautilus)

Incredible. Birds are badass (and also basically dinosaurs).

Montaigne Fled the Plague, and Found Himself

In the many essays of his life he discovered the importance of the moderate life. In his final essay, “On Experience,” Montaigne reveals that “greatness of soul is not so much pressing upward and forward as knowing how to circumscribe and set oneself in order.” What he finds, quite simply, is the importance of the moderate life. We must then, he writes, “compose our character, not compose books.” There is nothing paradoxical about this because his literary essays helped him better essay his life. The lesson he takes from this trial might be relevant for our own trial: “Our great and glorious masterpiece is to live properly.”

Robert Zaresky (The New York Times)

Every week, Bryan Alexander replies to the weekly Thought Shrapnel newsletter. Last week, he sent this article to both me and Chris Lott (who produces the excellent Notabilia).

We had a bit of a chat, with us sharing our love of How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at An Answer by Sarah Bakewell, and well as the useful tidbits it's possible glean from Stefan Zweig's short biography simply entitled Montaigne.

Header image by Nicolas Comte

Arguing that you don't care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don't care about free speech because you have nothing to say

Post-pandemic surveillance culture

Today's title comes from Edward Snowden, and is a pithy overview of the 'nothing to hide' argument that I guess I've struggled to answer over the years. I'm usually so shocked that an intelligent person would say something to that effect, that I'm not sure how to reply.

When you say, ‘I have nothing to hide,’ you’re saying, ‘I don’t care about this right.’ You’re saying, ‘I don’t have this right, because I’ve got to the point where I have to justify it.’ The way rights work is, the government has to justify its intrusion into your rights.

Edward Snowden

This, then, is the fifth article in my ongoing blogchain about post-pandemic society, which already includes:

It does not surprise me that those with either a loose grip on how the world works, or those who need to believe that someone, somewhere has 'a plan', believe in conspiracy theories around the pandemic.

What is true, and what can easily be mistaken for 'planning' is the preparedness of those with a strong ideology to double-down on it during a crisis. People and organisations reveal their true colours under stress. What was previously a long game now becomes a short-term priority.

For example, this week, the US Senate "voted to give law enforcement agencies access to web browsing data without a warrant", reports VICE. What's interesting, and concerning to me, is that Big Tech and governments are acting like they've already won the war on harvesting our online life, and now they're after our offline life, too.

I have huge reservations about the speed in which Covid-19 apps for contact tracing are being launched when, ultimately, they're likely to be largely ineffective.

We already know how to do contact tracing well and to train people how to do it. But, of course, it costs money and is an investment in people instead of technology, and privacy instead of surveillance.

There are plenty of articles out there on the difference between the types of contact tracing apps that are being developed, and this BBC News article has a useful diagram showing the differences between the two.

TL;DR: there is no way that kind of app is going on my phone. I can't imagine anyone who I know who understands tech even a little bit installing it either.

Whatever the mechanics of how it goes about doing it happen to be, the whole point of a contact tracing app is to alert you and the authorities when you have been in contact with someone with the virus. Depending on the wider context, that may or may not be useful to you and society.

However, such apps are more widely applicable. One of the things about technology is to think about the effects it could have. What else could an app like this have, especially if it's baked into the operating systems of devices used by 99% of smartphone users worldwide?

The above diagram is Marshall McLuhan's tetrad of media effects, which is a useful frame for thinking about the impact of technology on society.

Big Tech and governments have our online social graphs, a global map of how everyone relates to everyone else in digital spaces. Now they're going after our offline social graphs too.

Exhibit A

The general reaction to this seemed to be one of eye-rolling and expressing some kind of Chinese exceptionalism when this was reported back in January.

Exhibit B

Today, this Boston Dynamics robot is trotting around parks in Singapore reminding everyone about social distancing. What are these robots doing in five years' time?

Exhibit C

Drones in different countries are disinfecting the streets. What's their role by 2030?

I think it's drones that concern me most of all. Places like Baltimore were already planning overhead surveillance pre-pandemic, and our current situation has only accelerated and exacerbated that trend.

In that case, it's US Predator drones that have previously been used to monitor and bomb places in the Middle East that are being deployed on the civilian population. These drones operate from a great height, unlike the kind of consumer drones that anyone can buy.

However, as was reported last year, we're on the cusp of photovoltaic drones that can fly for days at a time:

This breakthrough has big implications for technologies that currently rely on heavy batteries for power. Thermophotovoltaics are an ultralight alternative power source that could allow drones and other unmanned aerial vehicles to operate continuously for days. It could also be used to power deep space probes for centuries and eventually an entire house with a generator the size of an envelope.

Linda Vu (TechXplore)

Not only will the government be able to fly thousands of low-cost drones to monitor the population, but they can buy technology, like this example from DefendTex, to take down other drones.

That is, of course, if civilian drones continue to be allowed, especially given the 'security risk' of Chinese-made drones flying around.

It's interesting times for those who keep a watchful eye on their civil liberties and government invasion of privacy. Bear that in mind when tech bros tell you not to fear robots because they're dumb. The people behind them aren't, and they have an agenda.

Header image via Pixabay

Friday featherings

Behold! The usual link round-up of interesting things I've read in the last week.

Feel free to let me know if anything particularly resonated with you via the comments section below...

Part I - What is a Weird Internet Career?

Weird Internet Careers are the kinds of jobs that are impossible to explain to your parents, people who somehow make a living from the internet, generally involving a changing mix of revenue streams. Weird Internet Career is a term I made up (it had no google results in quotes before I started using it), but once you start noticing them, you’ll see them everywhere.

Gretchen McCulloch (All Things Linguistic)

I love this phrase, which I came across via Dan Hon's newsletter. This is the first in a whole series of posts, which I am yet to explore in its entirety. My aim in life is now to make my career progressively more (internet) weird.

Nearly half of Americans didn’t go outside to recreate in 2018. That has the outdoor industry worried.

While the Outdoor Foundation’s 2019 Outdoor Participation Report showed that while a bit more than half of Americans went outside to play at least once in 2018, nearly half did not go outside for recreation at all. Americans went on 1 billion fewer outdoor outings in 2018 than they did in 2008. The number of adolescents ages 6 to 12 who recreate outdoors has fallen four years in a row, dropping more than 3% since 2007

The number of outings for kids has fallen 15% since 2012. The number of moderate outdoor recreation participants declined, and only 18% of Americans played outside at least once a week.

Jason Blevins (The Colorado Sun)

One of Bruce Willis' lesser-known films is Surrogates (2009). It's a short, pretty average film with a really interesting central premise: most people stay at home and send their surrogates out into the world. Over a decade after the film was released, a combination of things (including virulent viruses, screen-focused leisure time, and safety fears) seem to suggest it might be a predictor of our medium-term future.

I’ll Never Go Back to Life Before GDPR

It’s also telling when you think about what lengths companies have had to go through to make the EU versions of their sites different. Complying with GDPR has not been cheap. Any online business could choose to follow GDPR by default across all regions and for all visitors. It would certainly simplify things. They don’t, though. The amount of money in data collection is too big.

Jill Duffy (OneZero)

This is a strangely-titled article, but a decent explainer on what the web looks and feels like to those outside the EU. The author is spot-on when she talks about how GDPR and the recent California Privacy Law could be applied everywhere, but they're not. Because surveillance capitalism.

You Are Now Remotely Controlled

The belief that privacy is private has left us careening toward a future that we did not choose, because it failed to reckon with the profound distinction between a society that insists upon sovereign individual rights and one that lives by the social relations of the one-way mirror. The lesson is that privacy is public — it is a collective good that is logically and morally inseparable from the values of human autonomy and self-determination upon which privacy depends and without which a democratic society is unimaginable.

Shoshana Zuboff (The New York Times)

I fear that the length of Zuboff's (excellent) book on surveillance capitalism, her use of terms in this article such as 'epistemic inequality, and the subtlety of her arguments, may mean that she's preaching to the choir here.

How to Raise Media-Savvy Kids in the Digital Age

The next time you snap a photo together at the park or a restaurant, try asking your child if it’s all right that you post it to social media. Use the opportunity to talk about who can see that photo and show them your privacy settings. Or if a news story about the algorithms on YouTube comes on television, ask them if they’ve ever been directed to a video they didn’t want to see.

Meghan Herbst (WIRED)

There's some useful advice in this WIRED article, especially that given by my friend Ian O'Byrne. The difficulty I've found is when one of your kids becomes a teenager and companies like Google contact them directly telling them they can have full control of their accounts, should they wish...

Control-F and Building Resilient Information Networks

One reason the best lack conviction, though, is time. They don’t have the time to get to the level of conviction they need, and it’s a knotty problem, because that level of care is precisely what makes their participation in the network beneficial. (In fact, when I ask people who have unintentionally spread misinformation why they did so, the most common answer I hear is that they were either pressed for time, or had a scarcity of attention to give to that moment)

But what if — and hear me out here — what if there was a way for people to quickly check whether linked articles actually supported the points they claimed to? Actually quoted things correctly? Actually provided the context of the original from which they quoted

And what if, by some miracle, that function was shipped with every laptop and tablet, and available in different versions for mobile devices?

This super-feature actually exists already, and it’s called control-f.

Roll the animated GIF!

Mike Caulfield (Hapgood)

I find it incredible, but absolutely believable, that only around 10% of internet users know how to use Ctrl-F to find something within a web page. On mobile, it's just as easy, as there's an option within most (all?) browsers to 'search within page'. I like Mike's work, as not only is it academic, it's incredibly practical.

EdX launches for-credit credentials that stack into bachelor's degrees

The MicroBachelors also mark a continued shift for EdX, which made its name as one of the first MOOC providers, to a wider variety of educational offerings

In 2018, EdX announced several online master's degrees with selective universities, including the Georgia Institute of Technology and the University of Texas at Austin.

Two years prior, it rolled out MicroMasters programs. Students can complete the series of graduate-level courses as a standalone credential or roll them into one of EdX's master's degrees.

That stackability was something EdX wanted to carry over into the MicroBachelors programs, Agarwal said. One key difference, however, is that the undergraduate programs will have an advising component, which the master's programs do not.

Natalie Schwartz (Education Dive)

This is largely a rewritten press release with a few extra links, but I found it interesting as it's a concrete example of a couple of things. First, the ongoing shift in Higher Education towards students-as-customers. Second, the viability of microcredentials as a 'stackable' way to build a portfolio of skills.

Note that, as a graduate of degrees in the Humanities, I'm not saying this approach can be used for everything, but for those using Higher Education as a means to an end, this is exactly what's required.

How much longer will we trust Google’s search results?

Today, I still trust Google to not allow business dealings to affect the rankings of its organic results, but how much does that matter if most people can’t visually tell the difference at first glance? And how much does that matter when certain sections of Google, like hotels and flights, do use paid inclusion? And how much does that matter when business dealings very likely do affect the outcome of what you get when you use the next generation of search, the Google Assistant?

Dieter Bohn (The Verge)

I've used DuckDuckGo as my go-to search engine for years now. It used to be that I'd have to switch to Google for around 10% of my searches. That's now down to zero.

Coaching – Ethics

One of the toughest situations for a product manager is when they spot a brewing ethical issue, but they’re not sure how they should handle the situation. Clearly this is going to be sensitive, and potentially emotional. Our best answer is to discover a solution that does not have these ethical concerns, but in some cases you won’t be able to, or may not have the time.

[...]

I rarely encourage people to leave their company, however, when it comes to those companies that are clearly ignoring the ethical implications of their work, I have and will continue to encourage people to leave.

Marty Cagan (SVPG)

As someone with a sensitive radar for these things, I've chosen to work with ethical people and for ethical organisations. As Cagan says in this post, if you're working for a company that ignores the ethical implications of their work, then you should leave. End of story.

Image via webcomic.name

Microcast #085 — Extensions for Mozilla Firefox

In the last quarter of 2019, I got rid of my Google Pixelbook and Chromebox, and switched full-time to Linux and Firefox.

I still need to dip into Chromium occasionally to use Loom but, on the whole, I'm really happy with my new setup. In this microcast, I go through my Firefox extensions and the reasons I have them installed.

Show notes

The following are links to the Firefox Add-ons directory:

I am not fond of expecting catastrophes, but there are cracks in the universe

So said Sydney Smith. Let's talk about surveillance. Let's talk about surveillance capitalism and surveillance humanitarianism. But first, let's talk about machine learning and algorithms; in other words, let's talk about what happens after all of that data is collected.

Writing in The Guardian, Sarah Marsh investigates local councils using "automated guidance systems" in an attempt to save money.

The systems are being deployed to provide automated guidance on benefit claims, prevent child abuse and allocate school places. But concerns have been raised about privacy and data security, the ability of council officials to understand how some of the systems work, and the difficulty for citizens in challenging automated decisions.

Sarah Marsh

The trouble is, they're not particularly effective:

It has emerged North Tyneside council has dropped TransUnion, whose system it used to check housing and council tax benefit claims. Welfare payments to an unknown number of people were wrongly delayed when the computer’s “predictive analytics” erroneously identified low-risk claims as high risk

Meanwhile, Hackney council in east London has dropped Xantura, another company, from a project to predict child abuse and intervene before it happens, saying it did not deliver the expected benefits. And Sunderland city council has not renewed a £4.5m data analytics contract for an “intelligence hub” provided by Palantir.

Sarah Marsh

When I was at Mozilla there were a number of colleagues there who had worked on the OFA (Obama For America) campaign. I remember one of them, a DevOps guy, expressing his concern that the infrastructure being built was all well and good when there's someone 'friendly' in the White House, but what comes next.

Well, we now know what comes next, on both sides of the Atlantic, and we can't put that genie back in its bottle. Swingeing cuts by successive Conservative governments over here, coupled with the Brexit time-and-money pit means that there's no attention or cash left.

If we stop and think about things for a second, we probably wouldn't don't want to live in a world where machines make decisions for us, based on algorithms devised by nerds. As Rose Eveleth discusses in a scathing article for Vox, this stuff isn't 'inevitable' — nor does it constitute a process of 'natural selection':

Often consumers don’t have much power of selection at all. Those who run small businesses find it nearly impossible to walk away from Facebook, Instagram, Yelp, Etsy, even Amazon. Employers often mandate that their workers use certain apps or systems like Zoom, Slack, and Google Docs. “It is only the hyper-privileged who are now saying, ‘I’m not going to give my kids this,’ or, ‘I’m not on social media,’” says Rumman Chowdhury, a data scientist at Accenture. “You actually have to be so comfortable in your privilege that you can opt out of things.”

And so we’re left with a tech world claiming to be driven by our desires when those decisions aren’t ones that most consumers feel good about. There’s a growing chasm between how everyday users feel about the technology around them and how companies decide what to make. And yet, these companies say they have our best interests in mind. We can’t go back, they say. We can’t stop the “natural evolution of technology.” But the “natural evolution of technology” was never a thing to begin with, and it’s time to question what “progress” actually means.

Rose Eveleth

I suppose the thing that concerns me the most is people in dire need being subject to impersonal technology for vital and life-saving aid.

For example, Mark Latonero, writing in The New York Times, talks about the growing dangers around what he calls 'surveillance humanitarianism':

By surveillance humanitarianism, I mean the enormous data collection systems deployed by aid organizations that inadvertently increase the vulnerability of people in urgent need.

Despite the best intentions, the decision to deploy technology like biometrics is built on a number of unproven assumptions, such as, technology solutions can fix deeply embedded political problems. And that auditing for fraud requires entire populations to be tracked using their personal data. And that experimental technologies will work as planned in a chaotic conflict setting. And last, that the ethics of consent don’t apply for people who are starving.

Mark Latonero

It's easy to think that this is an emergency, so we should just do whatever is necessary. But Latonero explains the risks, arguing that the risk is shifted to a later time:

If an individual or group’s data is compromised or leaked to a warring faction, it could result in violent retribution for those perceived to be on the wrong side of the conflict. When I spoke with officials providing medical aid to Syrian refugees in Greece, they were so concerned that the Syrian military might hack into their database that they simply treated patients without collecting any personal data. The fact that the Houthis are vying for access to civilian data only elevates the risk of collecting and storing biometrics in the first place.

Mark Latonero

There was a rather startling article in last weekend's newspaper, which I've found online. Hannah Devlin, again writing in The Guardian (which is a good source of information for those concerned with surveillance) writes about a perfect storm of social media and improved processing speeds:

[I]n the past three years, the performance of facial recognition has stepped up dramatically. Independent tests by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (Nist) found the failure rate for finding a target picture in a database of 12m faces had dropped from 5% in 2010 to 0.1% this year.

The rapid acceleration is thanks, in part, to the goldmine of face images that have been uploaded to Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and captioned news articles in the past decade. At one time, scientists would create bespoke databases by laboriously photographing hundreds of volunteers at different angles, in different lighting conditions. By 2016, Microsoft had published a dataset, MS Celeb, with 10m face images of 100,000 people harvested from search engines – they included celebrities, broadcasters, business people and anyone with multiple tagged pictures that had been uploaded under a Creative Commons licence, allowing them to be used for research. The dataset was quietly deleted in June, after it emerged that it may have aided the development of software used by the Chinese state to control its Uighur population.

In parallel, hardware companies have developed a new generation of powerful processing chips, called Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), uniquely adapted to crunch through a colossal number of calculations every second. The combination of big data and GPUs paved the way for an entirely new approach to facial recognition, called deep learning, which is powering a wider AI revolution.

Hannah Devlin

Those of you who have read this far and are expecting some big reveal are going to be disappointed. I don't have any 'answers' to these problems. I guess I've been guilty, like many of us have, of the kind of 'privacy nihilism' mentioned by Ian Bogost in The Atlantic:

Online services are only accelerating the reach and impact of data-intelligence practices that stretch back decades. They have collected your personal data, with and without your permission, from employers, public records, purchases, banking activity, educational history, and hundreds more sources. They have connected it, recombined it, bought it, and sold it. Processed foods look wholesome compared to your processed data, scattered to the winds of a thousand databases. Everything you have done has been recorded, munged, and spat back at you to benefit sellers, advertisers, and the brokers who service them. It has been for a long time, and it’s not going to stop. The age of privacy nihilism is here, and it’s time to face the dark hollow of its pervasive void.

Ian Bogost

The only forces that we have to stop this are collective action, and governmental action. My concern is that we don't have the digital savvy to do the former, and there's definitely the lack of will in respect of the latter. Troubling times.

Friday fluctuations

Have a quick skim through these links that I came across this week and found interesting:

Image from Do It Yurtself

Friday feudalism

Check out these things I discovered this week, and wanted to pass along:

Friday fathomings

I enjoyed reading these:

Image via Indexed

Wretched is a mind anxious about the future

So said one of my favourite non-fiction authors, the 16th century proto-blogger Michel de Montaigne. There's plenty of writing about how we need to be anxious because of the drift towards a future of surveillance states. Eventually, because it's not currently affecting us here and now, we become blasé. We forget that it's already the lived experience for hundreds of millions of people.

Take China, for example. In The Atlantic, Derek Thompson writes about the Chinese government's brutality against the Muslim Uyghur population in the western province of Xinjiang:

[The] horrifying situation is built on the scaffolding of mass surveillance. Cameras fill the marketplaces and intersections of the key city of Kashgar. Recording devices are placed in homes and even in bathrooms. Checkpoints that limit the movement of Muslims are often outfitted with facial-recognition devices to vacuum up the population’s biometric data. As China seeks to export its suite of surveillance tech around the world, Xinjiang is a kind of R&D incubator, with the local Muslim population serving as guinea pigs in a laboratory for the deprivation of human rights.

Derek Thompson

As Ian Welsh points out, surveillance states usually involve us in the West pointing towards places like China and shaking our heads. However, if you step back a moment and remember that societies like the US and UK are becoming more unequal over time, then perhaps we're the ones who should be worried:

The endgame, as I’ve been pointing out for years, is a society in which where you are and what you’re doing, and have done is, always known, or at least knowable. And that information is known forever, so the moment someone with power wants to take you out, they can go back thru your life in minute detail. If laws or norms change so that what was OK 10 or 30 years ago isn’t OK now, well they can get you on that.

Ian Welsh

As the world becomes more unequal, the position of elites becomes more perilous, hence Silicon Valley billionaires preparing boltholes in New Zealand. Ironically, they're looking for places where they can't be found, while making serious money from providing surveillance technology. Instead of solving the inequality, they attempt to insulate themselves from the effect of that inequality.

A lot of the crazy amounts of money earned in Silicon Valley comes at the price of infringing our privacy. I've spent a long time thinking about quite nebulous concept. It's not the easiest thing to understand when you examine it more closely.

Privacy is usually considered a freedom from rather than a freedom to, as in "freedom from surveillance". The trouble is that there are many kinds of surveillance, and some of these we actively encourage. A quick example: I know of at least one family that share their location with one another all of the time. At the same time, of course, they're sharing it with the company that provides that service.

There's a lot of power in the 'default' privacy settings devices and applications come with. People tend to go with whatever comes as standard. Sidney Fussell writes in The Atlantic that:

Many apps and products are initially set up to be public: Instagram accounts are open to everyone until you lock them... Even when companies announce convenient shortcuts for enhancing security, their products can never become truly private. Strangers may not be able to see your selfies, but you have no way to untether yourself from the larger ad-targeting ecosystem.

Sidney Fussell

Some of us (including me) are willing to trade some of that privacy for more personalised services that somehow make our lives easier. The tricky thing is when it comes to employers and state surveillance. In these cases there are coercive power relationships at play, rather than just convenience.

Ellen Sheng, writing for CNBC explains how employees in the US are at huge risk from workplace surveillance:

In the workplace, almost any consumer privacy law can be waived. Even if companies give employees a choice about whether or not they want to participate, it’s not hard to force employees to agree. That is, unless lawmakers introduce laws that explicitly state a company can’t make workers agree to a technology...

One example: Companies are increasingly interested in employee social media posts out of concern that employee posts could reflect poorly on the company. A teacher’s aide in Michigan was suspended in 2012 after refusing to share her Facebook page with the school’s superintendent following complaints about a photo she had posted. Since then, dozens of similar cases prompted lawmakers to take action. More than 16 states have passed social media protections for individuals.

Ellen Sheng

It's not just workplaces, though. Schools are hotbeds for new surveillance technologies, as Benjamin Herold notes in an article for Education Week:

Social media monitoring companies track the posts of everyone in the areas surrounding schools, including adults. Other companies scan the private digital content of millions of students using district-issued computers and accounts. Those services are complemented with tip-reporting apps, facial-recognition software, and other new technology systems.

[...]

While schools are typically quiet about their monitoring of public social media posts, they generally disclose to students and parents when digital content created on district-issued devices and accounts will be monitored. Such surveillance is typically done in accordance with schools’ responsible-use policies, which students and parents must agree to in order to use districts’ devices, networks, and accounts.

Benjamin Herold

Hypothetically, students and families can opt out of using that technology. But doing so would make participating in the educational life of most schools exceedingly difficult.

In China, of course, a social credit system makes all of this a million times worse, but we in the West aren't heading in a great direction either.

We're entering a time where, by the time my children are my age, companies, employers, and the state could have decades of data from when they entered the school system through to them finding jobs, and becoming parents themselves.

There are upsides to all of this data, obviously. But I think that in the midst of privacy-focused conversations about Amazon's smart speakers and Google location-sharing, we might be missing the bigger picture around surveillance by educational institutions, employers, and governments.

Returning to Ian Welsh to finish up, remember that it's the coercive power relationships that make surveillance a bad thing:

Surveillance societies are sterile societies. Everyone does what they’re supposed to do all the time, and because we become what we do, it affects our personalities. It particularly affects our creativity, and is a large part of why Communist surveillance societies were less creative than the West, particularly as their police states ramped up.

Ian Welsh

We don't want to think about all of this, though, do we?

Also check out:

The drawbacks of Artificial Intelligence

It’s really interesting to do philosophical thought experiments with kids. For example, the trolley problem, a staple of undergradate Philosophy courses, is also accessible to children from a fairly young age.

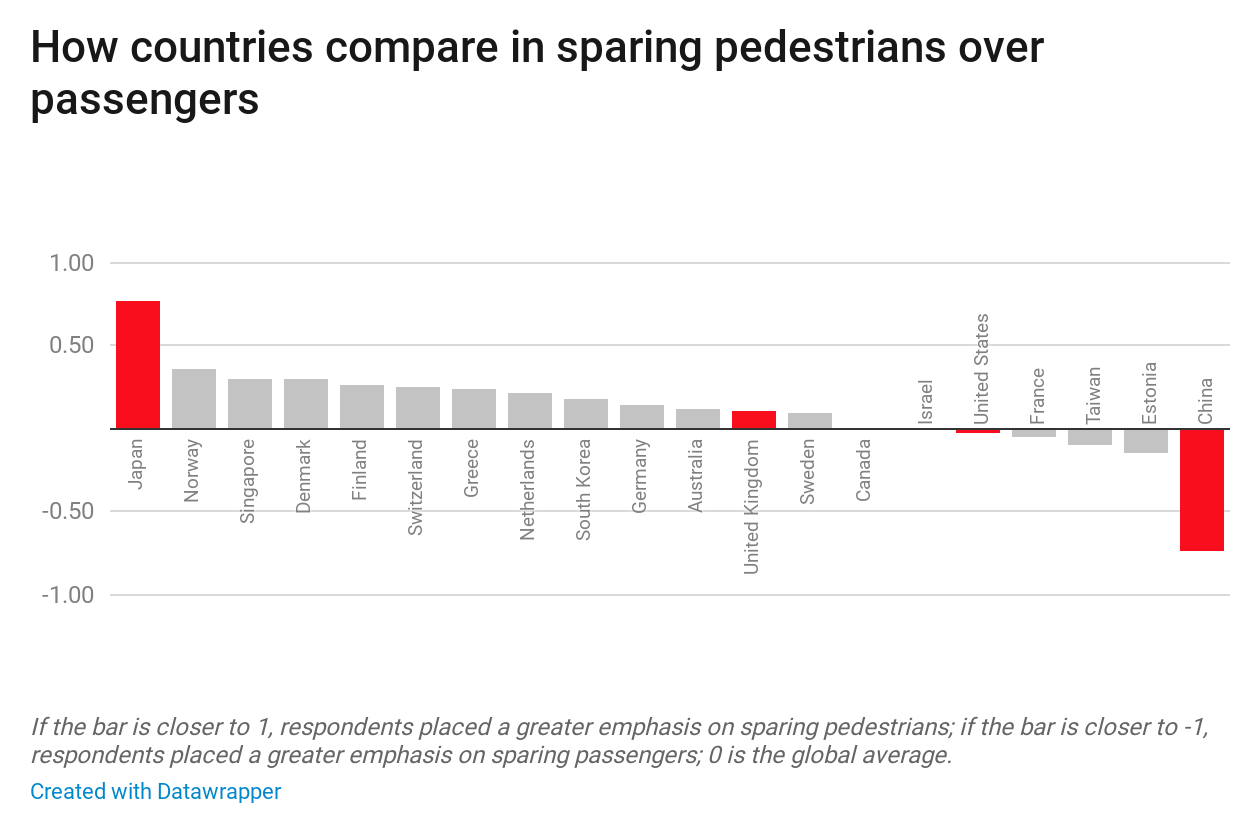

You see a runaway trolley moving toward five tied-up (or otherwise incapacitated) people lying on the tracks. You are standing next to a lever that controls a switch. If you pull the lever, the trolley will be redirected onto a side track, and the five people on the main track will be saved. However, there is a single person lying on the side track. You have two options:With the advent of autonomous vehicles, these are no longer idle questions. The vehicles, which have to make split-second decision, may have to decide whether to hit a pram containing a baby, or swerve and hit a couple of pensioners. Due to cultural differences, even that's not something that can be easily programmed, as the diagram below demonstrates.Which is the more ethical option?

For two countries that are so close together, it’s really interesting that Japan and China are on the opposite ends of the spectrum when it comes to saving passengers or pedestrians!

The authors of the paper cited in the article are careful to point out that countries shouldn’t simply create laws based on popular opinion:

Edmond Awad, an author of the paper, brought up the social status comparison as an example. “It seems concerning that people found it okay to a significant degree to spare higher status over lower status,” he said. “It's important to say, ‘Hey, we could quantify that’ instead of saying, ‘Oh, maybe we should use that.’” The results, he said, should be used by industry and government as a foundation for understanding how the public would react to the ethics of different design and policy decisions.This is why we need more people with a background in the Humanities in tech, and be having a real conversation about ethics and AI.

Of course, that’s easier said than done, particularly when those companies who are in a position to make significant strides in this regard have near-monopolies in their field and are pulling in eye-watering amounts of money. A recent example of this, where Google convened an AI ethics committee was attacked as a smokescreen:

As we saw around privacy, it takes a trusted multi-national body like the European Union to create a regulatory framework like GDPR for these issues. Thankfully, they've started that process by releasing guidelines containing seven requirements to create trustworthy AI:Academic Ben Wagner says tech’s enthusiasm for ethics paraphernalia is just “ethics washing,” a strategy to avoid government regulation. When researchers uncover new ways for technology to harm marginalized groups or infringe on civil liberties, tech companies can point to their boards and charters and say, “Look, we’re doing something.” It deflects criticism, and because the boards lack any power, it means the companies don’t change.

[...]“It’s not that people are against governance bodies, but we have no transparency into how they’re built,” [Rumman] Chowdhury [a data scientist and lead for responsible AI at management consultancy Accenture] tells The Verge. With regard to Google’s most recent board, she says, “This board cannot make changes, it can just make suggestions. They can’t talk about it with the public. So what oversight capabilities do they have?”

The problem isn't that people are going out of their way to build malevolent systems to rob us of our humanity. As usual, bad things happen because of more mundane requirements. For example, The Guardian has recently reported on concerns around predictive policing and hospitals using AI to predict everything from no-shows to risk of illness.

When we throw facial recognition into the mix, things get particularly scary. It’s all very well for Taylor Swift to use this technology to identify stalkers at her concerts, but given its massive drawbacks, perhaps we should restrict facial recognition somehow?

Human bias can seep into AI systems. Amazon abandoned a recruiting algorithm after it was shown to favor men’s resumes over women’s; researchers concluded an algorithm used in courtroom sentencing was more lenient to white people than to black people; a study found that mortgage algorithms discriminate against Latino and African American borrowers.Facial recognition might be a cool way to unlock your phone, but the kind of micro-expressions that made for great television in the series Lie to Me is now easily exploited in what is expected to become a $20bn industry.

The difficult thing with all of this is that it’s very difficult for us as individuals to make a difference here. The problem needs to be tackled at a much higher level, as with GDPR. That will take time, and meanwhile the use of AI is exploding. Be careful out there.

Also check out:

Location data in old tweets

What use are old tweets? Do you look back through them? If not, then they’re only useful to others, who are able to data mine you using a new toold:

The tool, called LPAuditor (short for Location Privacy Auditor), exploits what the researchers call an "invasive policy" Twitter deployed after it introduced the ability to tag tweets with a location in 2009. For years, users who chose to geotag tweets with any location, even something as geographically broad as “New York City,” also automatically gave their precise GPS coordinates. Users wouldn’t see the coordinates displayed on Twitter. Nor would their followers. But the GPS information would still be included in the tweet’s metadata and accessible through Twitter’s API.I deleted around 77,500 tweets in 2017 for exactly this kind of reason.

Source: WIRED