- Our inability to distinguish between confidence and competence

- Our love of charasmatic individuals

- The allure of “people with grandiose visions that tap into our own narcissism”

- Blood money is fine with us, says GitLab: Vetting non-evil customers is 'time consuming, potentially distracting' (The Register)

- Revealed: Google made large contributions to climate change deniers (The Guardian)

- Lenovo X270 (Wikipedia)

- Debian Linux

- Asus VivoMini (Wikipedia)

- Don’t ask forgiveness, radiate intent (Elizabeth Ayer) — "I certainly don’t need a reputation as being underhanded or an organizational problem. Especially as a repeat behavior, signalling builds me a track record of openness and predictability, even as I take risks or push boundaries."

- When will we have flying cars? Maybe sooner than you think. (MIT Technology Review) — "An automated air traffic management system in constant communication with every flying car could route them to prevent collisions, with human operators on the ground ready to take over by remote control in an emergency. Still, existing laws and public fears mean there’ll probably have to be pilots at least for a while, even if only as a backup to an autonomous system."

- For Smart Animals, Octopuses Are Very Weird (The Atlantic) — "Unencumbered by a shell, cephalopods became flexible in both body and mind... They could move faster, expand into new habitats, insinuate their arms into crevices in search of prey."

- Cannabidiol in Anxiety and Sleep: A Large Case Series. (PubMed) — "The final sample consisted of 72 adults presenting with primary concerns of anxiety (n = 47) or poor sleep (n = 25). Anxiety scores decreased within the first month in 57 patients (79.2%) and remained decreased during the study duration. Sleep scores improved within the first month in 48 patients (66.7%) but fluctuated over time. In this chart review, CBD was well tolerated in all but 3 patients."

- 22 Lessons I'm Still Learning at 82 (Coach George Raveling) — "We must always fill ourselves with more questions than answers. You should never retire your mind. After you retire mentally, then you are just taking up residence in society. I do not ever just want to be a resident of society. I want to be a contributor to our communities."

- How Boris Johnson's "model bus hobby" non sequitur manipulated the public discourse and his search results (BoingBoing) — "Remember, any time a politician deliberately acts like an idiot in public, there's a good chance that they're doing it deliberately, and even if they're not, public idiocy can be very useful indeed."

- It’s not that we’ve failed to rein in Facebook and Google. We’ve not even tried. (The Guardian) — "Surveillance capitalism is not the same as digital technology. It is an economic logic that has hijacked the digital for its own purposes. The logic of surveillance capitalism begins with unilaterally claiming private human experience as free raw material for production and sales."

- Choose Boring Technology (Dan McKinley) — "The nice thing about boringness (so constrained) is that the capabilities of these things are well understood. But more importantly, their failure modes are well understood."

- What makes a good excuse? A Cambridge philosopher may have the answer (University of Cambridge) — "Intentions are plans for action. To say that your intention was morally adequate is to say that your plan for action was morally sound. So when you make an excuse, you plead that your plan for action was morally fine – it’s just that something went awry in putting it into practice."

- Your Focus Is Priceless. Stop Giving It Away. (Forge) — "To virtually everyone who isn’t you, your focus is a commodity. It is being amassed, collected, repackaged and sold en masse. This makes your attention extremely valuable in aggregate. Collectively, audiences are worth a whole lot. But individually, your attention and my attention don’t mean anything to the eyeball aggregators. It’s a drop in their growing ocean. It’s essentially nothing."

- Be thorough and excellent in everything that you do

- Be smart and funny

- Be disarmingly honest

- Work without division of any kind

- Practise servant leadership

- People Who Claim to Work 75-Hour Weeks Usually Only Work About 50 Hours (New York Magazine) — "People overestimate how often they do all sorts of things they “ought” to be doing, often by even larger margins than with work for pay."

- Employee privacy in the US is at stake as corporate surveillance technology monitors workers’ every move (CNBC) — "In the workplace, almost any consumer privacy law can be waived. Even if companies give employees a choice about whether or not they want to participate, it’s not hard to force employees to agree."

- Workers Should Be in Charge (Jacobin) — "Every day, private equity companies snatch up firms and strip them dry. But there’s an alternative: allow workers to buy their workplace and run it themselves."

- Confusion → lack of Vision: note that this can be a proper lack of vision, or the lack of understanding of that vision, often due to poor communication and syncrhonization [sic] of the people involved.

- Anxiety → lack of Skills: this means that the people involved need to have the ability to do the transformation itself and even more importantly to be skilled enough to thrive once the transformation is completed.

- Resistance → lack of Incentives: incentives are important as people tend to have a big inertia to change, not just for fear generated by the unknown, but also because changing takes energy and as such there needs to be a way to offset that effort.

- Frustration → lack of Resources: sometimes change requires very little in terms of practical resources, but a lot in terms of time of the individuals involved (i.e. to learn a new way to do things), lacking resources will make progress very slow and it’s very frustrating to see that everything is aligned and ready, but doesn’t progress.

- False Starts → lack of Action Plan: action plans don’t have to be too complicated, as small transformative changes can be done with little structure, yet, structure has to be there. For example it’s very useful to have one person to lead the charge, and everyone else agreeing they are the right person to make things happen.

- Connect to a mission and purpose

- Reconsider your view of failure

- Cultivate a sense of ownership

- Connect to a mission and purpose

- Reconsider your view of failure

- Cultivate a sense of ownership

- Availability of additional communication mechanisms

- Failure of other communication avenues

- Consequences of anonymity

- Designing the anonymous communication channel

- Long-term considerations

- Hire people who like to work hard and who have something to prove.

- Encourage people to own and manage large blocks of their own time, and give people time to think and make thinking part of the job—not extra.

- Let people rest. Encourage them to go home at sensible times. If they work late give them time off to make up for it.

- Aim for consistency. Set emotional boundaries and expectations, be clear about rewards, and protect people where possible from crises so they can plan their time.

- Make their success their own and credit them for it.

- Don’t promise happiness. Promise fair pay and good work.

OKRs as institutional memory

Rick Klau, formerly of Google Ventures, is a big fan of OKRs (or ‘Objectives and Key Results’). They’re different from KPIs (or ‘Key Performance Indicators’) for various reasons, including the fact that they’re transparent to everyone in the organisation, and build on one another towards organisational goals.

In this post, Klau talks about OKRs as a form of organisational memory, which is why he’s not fond of changing them half-way through a cycle just because there’s new information available.

Let’s not distract ourselves just because someone had a good idea on a Tuesday standup meeting; let’s finish the stuff we said we were going to do. We might not succeed at all of it. In fact, we probably won’t, but we’ll have learned more and more. You can encode that. That becomes part of the institutional memory at the organization. (link and emphasis mine)Source: OKRs as institutional memory | tins ::: Rick Klau's weblog

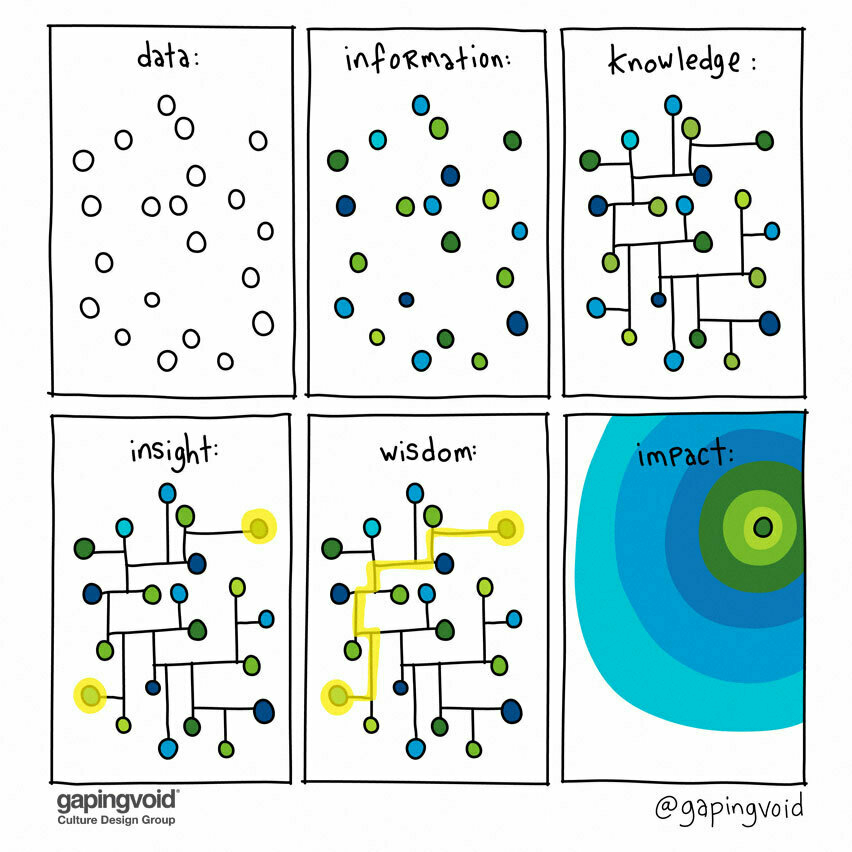

Information is not knowledge (and knowledge is not wisdom)

Some reflections by Nick Milton on why knowledge management within organisations is so poor. If I were him, I would have included the below illustration from gapingvoid as I think it illustrates his five points rather well.

Firstly much of the knowledge of the organisation is never codified as information.Source: Why you can’t solve knowledge problems with information tools alone | Knoco Stories[…]

Secondly, a common problem (a corollary of the first) is that project knowledge may never have been recorded in project documents.

[…]

Thirdly, and a corollary to the first two, the vast majority of project information is not knowledge anyway. If you are relying on project documents as a source of knowledge, you will be relying on a very diluted source - a lot of noise and not much signal.

[…]

Fourthly, if there is codified knowledge in the project documents, it tends to be scattered across many documents and many projects.

[…]

Finally, many of the knowledge problems are cultural. People are incentivised to rush on to the next job rather than to spend time reflecting on lessons, no matter how important.

Let's talk

Wise words from Seth Godin:

Universities and local schools are in crisis with testing in disarray and distant learning ineffective…

[When can we talk about what school is for?]

It’s comfortable to ignore the system, to assume it is as permanent as the water surrounding your goldfish. But the fact that we have these tactical problems is all the evidence we need to see that something is causing them, and that spending time on the underlying structure could make a difference.

Seth Godin, When can we talk about our systems?

It's not just education, or racism, or healthcare, or any of the other things he lists. Organisations are made up of people, and most people don't like conflict.

As a result, we get a constant barrage of tactical responses to emergent situations, rather than focusing on strategies that would prevent them.

The more time we spend on purposeful reflection, the less time we spend putting out fires.

How you do anything is how you do everything

So said Derek Sivers, although I suspect that, originally, it's probably a core principle of Zen Buddhism. In this article I want to talk about management and leadership. But also about emotional intelligence and integrity.

I currently spend part of my working life as a Product Manager. At some organisations, this means that you're in charge of the budget, and pull in colleagues from different disciplines. For example, a designer you're working with on a particular project might report to the Head of UX. Matrix-style management and internal budgeting keeps track of everything.

This approach can get complicated so, at other companies (like the one I'm working with), the Product Manager manages both people and product. It's a lot of work, as both can be complicated.

I think I'm OK at managing people, and other people say I'm good at it, but it's not my favourite thing in the world to do.

That's why, when hiring, I try to do so in one of three ways. Ideally, I want to hire people with whom at least one member of the existing team has already worked and can vouch for. If that doesn't work, then I'm looking for people vouched for my the networks of which the team are part. Failing that, I'm trying to find people who don't wait for direction, but know how to get on with things that need doing.

It's an approach I've developed from the work of Laura Thomson. She's a former colleague at Mozilla, and an advocate of a chaordic style of management and self-organising ducks:

Instead of having ‘all your ducks in a row’ the analogy in chaordic management is to have ‘self-organising ducks’. The idea is to give people enough autonomy, knowledge and skill to be able to do the management themselves.

As I've said before, the default way of organising human beings is hierarchy. That doesn't mean it's the best way. Hierachy tends to lean on processes, paperwork and meetings to 'get things done' but even a cursory glance at Open Source projects shows that all of this isn't strictly necessary.

Last week, a new-ish member of the team said that I can be "too nice". I'm still processing that and digging into what they meant, but I then ended up reading an article by Roddy Millar for Fast Company entitled Here’s why being likable may make you a less effective leader.

It's a slightly oddly-framed article that quotes Prof. Karen Cates from Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management :

Leaders should not put likability above effectiveness. There are times when the humor and smiles need to go and a let’s-get-this-done approach is required. Cates goes further: “Even the ‘nasty boss approach’ can be really effective—but in short, small doses—to get everyone’s attention and say ‘Hey, we’ve got to make some changes around here.’ You can then create—with an earnest approach—that more likable persona as you move forward. Likability is a good thing to have in your leadership toolkit, but it shouldn’t be the biggest hammer in the box.”

Roddy Millar

I think there's a difference between 'trying to be likeable' and 'treating your colleagues with dignity and respect'.

If you're being nice to be just to liked by your team, you're probably doing it wrong. It's a bit like, back when I was teaching, teachers who wanted to be liked by the kids they taught.

The other approach is to simply treat the people around you with dignity and respect, realising that all of human life involves suffering, so let's not add to the burden through our everyday working lives.

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The above is one of my favourite quotations. We don't need to crack the whip or wield some kind of totem of hierarchical power over other people. We just need to ensure people are in the right place (physically and emotoinally), with the right things (tools, skills, and information) to get things done.

In managers are for caring, Harold Jarche points a finger at hierarchical organisations, stating that they are "what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator".

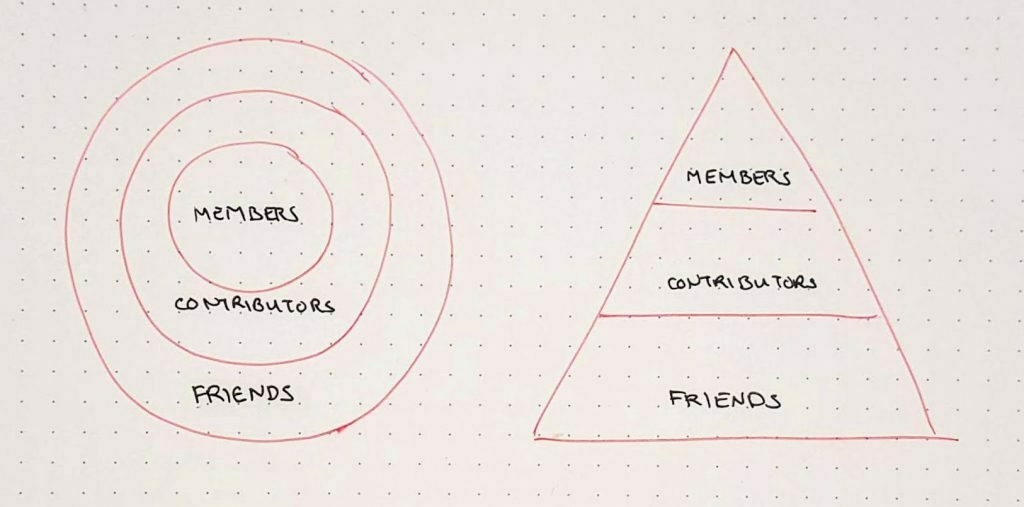

Jarche wonders instead what would happen if they were structured more like communities of practice?

What would an organization look like with looser hierarchies and stronger networks? A lot more human, retrieving some of the intimacy and cooperation of tribal groups. We already have other ways of organizing work. Orchestras are not teams, and neither are jazz ensembles. There may be teamwork on a theatre production but the cast is not a team. It is more like a community of practice, with strong and weak social ties.

Harold Jarche

I think part of the problem, to be honest, is emotional intelligence, or rather the lack of it, in many organisations.

Unfortunately, the way to earn more money in organisations is to start managing people. Which is fine for the subset of people who have the skills to be able to handle this. For others, it's a frustrating experience that takes them away from doing the work.

For TED Ideas, organisational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic asks Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? And what can we do about it? He lists three reasons why we have so many incompetent (male) leaders:

He suggests three ways to fix this. The other two are all well and good, but I just want to focus on the first solution he suggests:

The first solution is to follow the signs and look for the qualities that actually make people better leaders. There is a pathological mismatch between the attributes that seduce us in a leader and those that are needed to be an effective leader. If we want to improve the performance of our leaders, we should focus on the right traits. Instead of falling for people who are confident, narcissistic and charismatic, we should promote people because of competence, humility and integrity. Incidentally, this would also lead to a higher proportion of female than male leaders — large-scale scientific studies show that women score higher than men on measures of competence, humility and integrity. But the point is that we would significantly improve the quality of our leaders.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

The best leaders I've worked for exhibited high levels of emotional intelligence. Most of them were women.

Developing emotional intelligence is difficult and goodness knows I'm no expert. What I think we perhaps need to do is to remove our corporate dependency on hierarchy. In hierarchies, emotion and trust is removed as an impediment to action.

However, in my experience, hierarchy is inherently patriarchal and competitive. It's not something that's necessarily useful in every industry in the 21st century. And hierarchies are not places that I, and people like me, particularly thrive.

Instead, I think we require trust-based ways of organising — ways that emphasis human relationships. I think these are also more conducive to human flourishing.

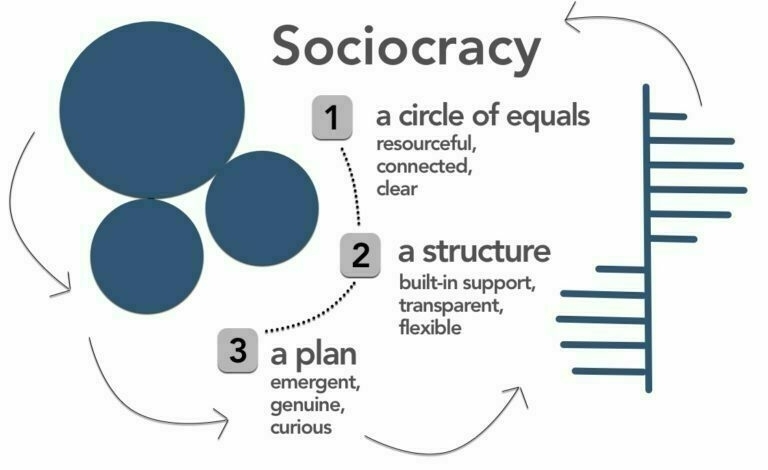

Right now, approaches such as sociocracy take a while to get our collective heads around as they're opposed to our "default operating system" of hierarchy. However, over time I think we'll see versions of this becoming the norm, as it becomes ever easier to co-ordinate people at a distance.

To sum up, what it means to be an effective leader is changing. Returning to the article cited above by Harold Jarche, he writes:

Hierarchical teams are what we get when we use the blunt stick of economic consequences with financial quid pro quo as the prime motivator. In a creative economy, the unity of hierarchical teams is counter-productive, as it shuts off opportunities for serendipity and innovation. In a complex and networked economy workers need more autonomy and managers should have less control.

Harold Jarche

Many people no longer live in a world of the 'permanent job' and 'career ladder'. What counts as success for them is not necessarily a steadily-increasing paycheck, but measures such as social justice or 'making a dent in the universe'. This is where hierarchy fails, and where emergent, emotionally-intelligent leaders with teams of self-organising ducks, thrive.

Microcast #078 — Values-based organisations

I've decided to post these microcasts, which I previously made available only through Patreon, here instead.

Microcasts focus on what I've been up to and thinking about, and also provide a way to answer questions from supporters and other readers/listeners!

This microcast covers ethics in decision-making for technology companies and (related!) some recent purchases I've made.

Show notes

Do not impose one's own standard on the work of others. Mutual moderation and cooperation will proffer better results.

I think I must have come across the above saying from Hsing Yun via Mayel de Borniol. It captures some of what I want to discuss in this article which centres around decision-making within organisations.

Let's start with a great article from Roman Imankulov from Doist. He looks to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)'s approach, as enshrined in a document from 2014, explaining their 'rough consensus' approach:

Rough consensus isn’t majority rule. It’s okay to go ahead with a solution that may not look like the best choice for everyone or even the majority. "Not the best choice" means that you believe there is a better way to solve the problem, but you accept that this one will work too. That type of feedback should be welcomed, but it shouldn’t be allowed to slow down a decision.

Roman Imankulov

If they try hard enough, everyone can come up with a reason why an idea or approach won't work. My experience is that many middle-aged white men see it as their sworn duty to come up with as many of those reasons as possible 🙄

What the IETF calls 'rough consensus' I think I'd probably call 'alignment'. You don't all have to agree that a proposal is without problems, but those problems should be surmountable. Within CoTech, a network of co-operatives to which We Are Open belongs, we use Loomio. It has a number of decision tools, including the 'proposal':

As you can see, there's the ability for anyone to 'Block' a proposal, meaning that it can't be passed in its current form. People can 'Abstain' if there's a conflict of interest, or if they don't feel like they've got enough experience or expertise. Note that it's entirely possible for someone to 'Disagree' and the motion to still go ahead.

What I like about Loomio is a tool is that it focuses on decision-making. It's not about endless discussion and debate, but about having a bias towards action. You can separate the planning process from the implementation stage:

Rough consensus doesn’t mean that we don’t aim for perfection in the actual implementation of the solution. When implementing, we should always aim for technical excellence. Commitment to the implementation is often what makes a solution the right one. (This is similar to Amazon’s "disagree and commitment" philosophy.)

Roman Imankulov

I can't, by my nature, stand hierarchy. Unfortunately, it's the default operating system of most organisations, and despite our best efforts, we haven't got a one-size-fits-all alternative to it. I think this is partly because nobody has to teach you how hierarchy works.

Over the weekend, while we were walking in the Lake District, Tom Broughton and I were discussing sociocracy:

Sociocracy, also known as dynamic governance, is a system of governance which seeks to achieve solutions that create harmonious social environments as well as productive organizations and businesses. It is distinguished by the use of consent rather than majority voting in decision-making, and decision-making after discussion by people who know each other.

Wikipedia

Tom's a Quaker and so used to consent-based decision-making. I explained that we'd asked Outlandish (a CoTech member) to run a sociocratic design sprint to kick off our work around MoodleNet. It was based on the Google design sprint approach, but — as Kayleigh from Outlandish points out — featured an important twist:

We decided to remove the ‘decider’ role that a Google Sprint employs. We weren’t comfortable with the responsibility and authority of decisions sitting with one person, and having spent a few years practising sociocracy already, it just wouldn’t have felt right.

[...]

Martin, Moodle’s CEO and founder joined us for the duration of the sprint. While Martin naturally had the most expertise in the domain, the most ‘skin in the game’ and the had done the most background thinking sociocracy meant that he still needed to convince the rest of the sprint team as to why his ideas were best, and take on board other suggestions and compromises. We feel that it led to better outputs at each stage of the design sprint.

Kayleigh Walsh

It was the first time I'd seen a CEO give up their hierarchical power in the interests of ensuring that we designed something that could be the best it could possibly be. In fact, that week last May is probably one of the highlights of my career to date.

That was one week into which was poured a lot of time, attention, and money. But what if you want to practise something like sociocracy on a day-to-day basis? You have to think about structure of organisations, as there's no such thing as 'structureless' group:

Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved. The very fact that we are individuals, with different talents, predispositions, and backgrounds makes this inevitable. Only if we refused to relate or interact on any basis whatsoever could we approximate structurelessness -- and that is not the nature of a human group.

Jo Freeman

It's only within the last year that I've discovered left-libertarianism as a coherent political and social philosophy that helps me reconcile two things that I've previously found difficult. On the one hand, I believe in a small state. On the other, I believe we have a duty to one another and should help out wherever possible.

Left-libertarianism, also known as left-wing libertarianism, names several related yet distinct approaches to political and social theory which stress both individual freedom and social equality. In its classical usage, left-libertarianism is a synonym for anti-authoritarian varieties of left-wing politics such as libertarian socialism which includes anarchism and libertarian Marxism among others.

[...]

While maintaining full respect for personal property, left-libertarians are skeptical of or fully against private ownership of natural resources, arguing in contrast to right-libertarians that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights and maintain that natural resources (raw land, oil, gold, the electromagnetic spectrum, air-space and so on) should be held in an egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively. Those left-libertarians who support private property do so under occupation and use property norms or under the condition that recompense is offered to the local or even global community.

Wikipedia

In other words, you don't have to be a Marxist, communist, or anarchist to be a left-libertarian. It means you can start from a basis of personal autonomy, but end with an egalitarian approach to the world where resources (especially natural resources) are collectively owned.

To me, this is the position from which we should start when we think about decision-making within organisations. First of all, we should ask: who owns the organisation? Why? Second, we should consider how the organisation should be structured. Ten layers of management might be bad, but so is a completely flat structure for 700 people. And finally, we should think about appropriate mechanisms for decision-making.

The usual criticisms of sociocracy and other consent-based decision-making systems is that they are too slow, that they don't work in practice. In my experience, by participating in the Outlandish/Moodle design sprint, witnessing a Mozilla Festival session in which participants quickly got up-to-speed on sociocracy, and through CoTech gatherings (both online and offline), I'd say sociocracy is a viable solution.

The best decisions aren't ones where you have all of the information to hand. That's impossible. The best decisions are based on trust and consent.

As I get older, I'm realising that the best way we can improve the world is to improve its governance. It's not that we haven't got extremely talented people in the world, it's that we don't always know how to make good decision. I'd like to change that.

Friday frustrations

I couldn't help but notice these things this week:

Image via @EffinBirds

Culture eats strategy for breakfast

The title of this post is a quotation from management consultant, educator, and author Peter Drucker. Having worked in a variety of organisations, I can attest to its truth.

That's why, when someone shared this post by Grace Krause, which is basically a poem about work culture, I paid attention. Entitled Appropriate Channels, here's a flavour:

We would like to remind you all

That we care deeply

About our staff and our students

And in no way do we wish to silence criticism

But please make use of the

Appropriate ChannelsThe Appropriate Channel is tears cried at home

And not in the workplace

Please refrain from crying at your desk

As it might lower the productivity of your colleagues

Organisational culture is difficult because of the patriarchy. I selected this part of the poem, as I've come to realise just how problematic it is to let people know (through words, actions, or policies) that it's not OK to cry at work. If we're to bring our full selves to work, then emotion is part of it.

Any organisation has a culture, and that culture can be changed, for better or for worse. Restaurants are notoriously toxic places to work, which is why this article in Quartz, is interesting:

Since four-time James Beard award winner Gabrielle Hamilton opened Prune’s doors in 1999, she, along with her co-chef Ashley Merriman, have established a set of principles that help guide employees at the restaurant. According to Hamilton and Merriman, the code has a kind of transformative power. It’s helped the kitchen avoid becoming a hierarchical, top-down fiefdom—a concentration of power that innumerable chefs have abused in the past. It can turn obnoxious, entitled patrons into polite diners who are delighted to have a seat at the table. And it’s created the kind of environment where Hamilton and Merriman, along with their staff, want to spend much of their day.

The five core values of their restaurant, which I think you could apply to any organisation, are:

We live in the 'age of burnout', according to another article in Quartz, but there's no reason why we can't love the work we do. It's all about finding the meaning behind the stuff we get done on a daily basis:

Our freedom to make meaning is both a blessing and a curse. To get somewhat existential about it, “work,” and the problems associated with it as an amorphous whole, do not exist: For the individual, only his or her work exists, and the individual is in control of that, with the very real power radically to change the situation. You could start the process of changing your job right now, today. Yes, arguments about the practicality of that choice well up fast and high. Yes, you would have to find another way to pay the bills. That doesn’t negate the fact that, fundamentally, you are free.

It's important to remember this, that we choose to do the work we do, that we don't have to work for a single employer, and that we can tell a different story about ourselves at any point we choose. It might not be easy, but it's certainly doable.

Also check out:

Hierarchies and large organisations

This 2008 post by Paul Graham, re-shared on Hacker News last week, struck a chord:

What's so unnatural about working for a big company? The root of the problem is that humans weren't meant to work in such large groups.I really enjoyed working at the Mozilla Foundation when it was around 25 people. By the time it got to 60? Not so much. It’s potentially different with every organisation, though, and how teams are set up.Another thing you notice when you see animals in the wild is that each species thrives in groups of a certain size. A herd of impalas might have 100 adults; baboons maybe 20; lions rarely 10. Humans also seem designed to work in groups, and what I’ve read about hunter-gatherers accords with research on organizations and my own experience to suggest roughly what the ideal size is: groups of 8 work well; by 20 they’re getting hard to manage; and a group of 50 is really unwieldy.

Graham goes on to talk about how, in large organisations, people are split into teams and put into a hierarchy. That means that groups of people are represented at a higher level by their boss:

A group of 10 people within a large organization is a kind of fake tribe. The number of people you interact with is about right. But something is missing: individual initiative. Tribes of hunter-gatherers have much more freedom. The leaders have a little more power than other members of the tribe, but they don't generally tell them what to do and when the way a boss can.These words may come back to haunt me, but I have no desire to work in a huge organisation. I’ve seen what it does to people — and Graham seems to agree:[…]

[W]orking in a group of 10 people within a large organization feels both right and wrong at the same time. On the surface it feels like the kind of group you’re meant to work in, but something major is missing. A job at a big company is like high fructose corn syrup: it has some of the qualities of things you’re meant to like, but is disastrously lacking in others.

The people who come to us from big companies often seem kind of conservative. It's hard to say how much is because big companies made them that way, and how much is the natural conservatism that made them work for the big companies in the first place. But certainly a large part of it is learned. I know because I've seen it burn off.Perhaps there's a happy medium? A four-day workweek gives scope to either work on a 'side hustle', volunteer, or do something that makes you happier. Maybe that's the way forward.

Source: Paul Graham

Implicit leverage

Tyler Cowen at Marginal Revolution asks how well we understand the organisations we work with and for:

Most (not all) organizations have forms of leverage which are built in and which do not show up as debt on the balance sheet. Banks may have off-balance sheet risk through derivatives, companies may sell off their valuable assets, and NBA teams may tank their ability to keep draft picks and free agents in their future.In other words, every organisation has people, other organisations, or resources on which it is dependent. That can look like event organisers not alienating a sponsor, universities maintaining their brand overseas so they can continue to recruit lucrative overseas students, and organisations doing well because of a handful of individuals that win investors' trust.

When it comes to politics, of course, ‘leverage’ is almost always something problematic. In fact, we usually use the phrase ‘in the pocket of’ instead to show our opprobrium when a politician has close financial ties to, say, a tobacco company or big business.

In other words, understanding how leverage works in everyday life, business, and politics is probably something we should be teaching in schools.

Source: Marginal Revolution

Image by Mike Cohen used under a Creative Commons License

On 'unique' organisational cultures

This article on Recode, which accompanies one of their podcast episodes, features some thoughts from Adam Grant, psychologist and management expert. A couple of things he says chime with my experience of going into a lot of organisations as a consultant, too:

Exactly. There's only so many ways you can slice and dice hierarchy, so people do exercises around corporate values and mission statements.“Almost every company I’ve gone into, what I hear is, ‘Our culture is unique!’” Grant said on the latest episode of Recode Decode, hosted by Kara Swisher. “And then I ask, ‘How is it unique?’ and the answers are all the same.”

If organisations really want to be innovative, they should empower their employees in ways beyond mere words. Perhaps by allowing them to be co-owners of the business, or by devolving power (and budget) to smaller, cross-functional teams?“I hear, ‘People really believe in our values and they think that we’re a cause, so we’re so passionate about the mission!’” he added. “Great. So is pretty much every other company. I hear, ‘We give employees unusual flexibility,’ ‘We have all sorts of benefits that no other company offers,’ and ‘We live with integrity in ways that no other company does.’ It’s just the same platitudes over and over.”

Another thing that Grant complains about is the idea of ‘cultural fit’. I can see why organisations do this as, after all, you do have to get on and work with the people you’re hiring. However, as he explains, it’s a self-defeating approach:

I haven't listened to the podcast yet, but the short article is solid stuff.Startups with a disruptive idea can use “culture fit” to hire a lot of people who all feel passionately about the mission of these potentially world-changing companies, Grant said. But then those people hire even more people who are like them.

“You end up attracting the same kinds of people because culture fit is a proxy for, ‘Are you similar to me? Do I want to hang out with you?’” he said. “So you end up with this nice, homogeneous group of people who fall into groupthink and then it’s easier for them to get disrupted from the outside, and they have trouble innovating and changing.”

Recode (via Stowe Boyd)

Rethinking hierarchy

This study featured on the blog of the Stanford Graduate School of Business talks about the difference between hierarchical and non-hierarchical structures. It cites work by Lisanne van Bunderen from University of Amsterdam, who found that egalitarianism seemed to lead to better performance:

Context, of course, is vital. One place where hierarchy and a command-and-control approach seems impotant is in high stakes situations such as the battlefield or hospital operating theatres during delicate operations. Lindred Greer, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, nevertheless believes that, even in these situations, the amount of hierarchy can be reduced:“The egalitarian teams were more focused on the group because they felt like ‘we’re in the same boat, we have a common fate,’” says van Bunderen. “They were able to work together, while the hierarchical team members felt a need to fend for themselves, likely at the expense of others.”

In some cases, hierarchy is an unavoidable part of the work. Greer is currently studying the interaction between surgeons and nurses, and surgeons lead by necessity. “If you took the surgeon out of the operating room, you would have some issues,” she says. But surgeons’ dominance in the operating room can also be problematic, creating dysfunctional power dynamics. To help solve this problem, Greer believes that the expression of hierarchy can be moderated. That is, surgeons can learn to behave in a way that’s less hierarchical.While hierarchy is necessary in some situations, what we need is a more fluid approach to organising, as I've written about recently. The article gives the very practical example of Navy SEALs:

Like the article's author, I'm still looking for something that's going to gain more traction than Holacracy. Perhaps the sociocratic approach could work well, but does require people to be inducted into it. After all, hierarchy and capitalism is what we're born into these days. It feels 'natural' to people.Navy SEALS exemplify this idea. Strict hierarchy dominates out in the field: When a leader says go left, they go left. But when the team returns for debrief, “they literally leave their stripes at the door,” says Greer. The hierarchy disappears; nobody is a leader, nobody a follower. “They fluidly shift out of these hierarchical structures,” she says. “It would be great if business leaders could do this too: Shift from top-down command to a position in which everyone has a say.” Importantly, she reiterated, this kind of change is not only about keeping employees happy, but also about enhancing performance and benefiting the bottom line.

Source: Stanford Graduate School of Business (via Stowe Boyd)

Systems change

Over the last 15 years that I’ve been in the workplace, I’ve worked in a variety of organisations. One thing I’ve found is that those that are poor at change management are sub-standard in other ways. That makes sense, of course, because life = change.

There’s a whole host of ways to understand change within organisations. Some people seem to think that applying the same template everywhere leads to good outcomes. They’re often management consultants. Others think that every context is so different that you just have to go with your gut.

I’m of the opinion that there are heuristics we can use to make our lives easier. Yes, every situation and every organisation is different, but that doesn’t mean we can’t apply some rules of thumb. That’s why I like this ‘Managing Complex Change Model’ from Lippitt (1987), which I discovered by going down a rabbithole on a blog post from Tom Critchlow to a blog called ‘Intense Minimalism’.

The diagram, included above is commented upon by

I'd perhaps use different words, as anxiety can be cause by a lot more than not having the skills within your team. But, otherwise, I think it's a solid overview and good reminder of the fundamental building blocks to system change.

Source: Intense Minimalism (via Tom Critchlow)

Owners need to invest in employees to have them feel invested in their work

Jim Whitehurst, CEO of Red Hat, writes:

As the nature of work changes, the factors keeping people invested in and motivated by that work are changing, too. What's clear is that our conventional strategies for cultivating engagement may no longer work. We need to rethink our approach.I think it's great that forward-thinking organisations are trying to find ways to make work more fulfilling, and be part of a more holistic approach to life.

Current research suggests that extrinsic rewards (like bonuses or promotions) are great at motivating people to perform routine tasks—but are actually counterproductive when we use them to motivate creative problem-solving or innovation. That means that the value of intrinsic motivation is rising, which is why cultivating employee engagement is such an important topic right now.Whitehurst suggests that there are three things organisations can do. I’d support all of these:Don’t get me wrong: I’m not suggesting that people no longer want to be paid for their work. But a paycheck alone is no longer enough to maintain engagement. As work becomes more difficult to specify and observe, managers have to ensure excellent performance via methods other than prescription, observation, and inspection. Micromanaging complex work is impossible.

Don’t get me wrong, forming a co-op doesn’t automatically guarantee worker satisfaction, but it’s a whole lot more motivating when you know you’re not just working to make someone else rich.

Source: opensource.com

Owners need to invest in employees to have them feel invested in their work

Jim Whitehurst, CEO of Red Hat, writes:

As the nature of work changes, the factors keeping people invested in and motivated by that work are changing, too. What's clear is that our conventional strategies for cultivating engagement may no longer work. We need to rethink our approach.I think it's great that forward-thinking organisations are trying to find ways to make work more fulfilling, and be part of a more holistic approach to life.

Current research suggests that extrinsic rewards (like bonuses or promotions) are great at motivating people to perform routine tasks—but are actually counterproductive when we use them to motivate creative problem-solving or innovation. That means that the value of intrinsic motivation is rising, which is why cultivating employee engagement is such an important topic right now.Whitehurst suggests that there are three things organisations can do. I’d support all of these:Don’t get me wrong: I’m not suggesting that people no longer want to be paid for their work. But a paycheck alone is no longer enough to maintain engagement. As work becomes more difficult to specify and observe, managers have to ensure excellent performance via methods other than prescription, observation, and inspection. Micromanaging complex work is impossible.

Don’t get me wrong, forming a co-op doesn’t automatically guarantee worker satisfaction, but it’s a whole lot more motivating when you know you’re not just working to make someone else rich.

Source: opensource.com

Anonymity vs accountability

As this article points out, organisational culture is a delicate balance between many things, including accountability and anonymity:

Though some assurance of anonymity is necessary in a few sensitive and exceptional scenarios, dependence on anonymous feedback channels within an organization may stunt the normalization of a culture that encourages diversity and community.Anonymity can be helpful and positive:

For example, an anonymous suggestion program to garner ideas from members or employees in an organization may strengthen inclusivity and enhance the diversity of suggestions the organization receives. It would also make for a more meritocratic decision-making process, as anonymity would ensure that the quality of the articulated idea, rather than the rank and reputation of the articulator, is what's under evaluation. Allowing members to anonymously vote for anonymously-submitted ideas would help curb the influence of office politics in decisions affecting the organization's growth....but also problematic:

Reliance on anonymous speech for serious organizational decision-making may also contribute to complacency in an organizational culture that falls short of openness. Outlets for anonymous speech may be as similar to open as crowdsourcing is—or rather, is not. Like efforts to crowdsource creative ideas, anonymous suggestion programs may create an organizational environment in which diverse perspectives are only valued when an organization's leaders find it convenient to take advantage of members' ideas.The author gives some advice to leaders under five sub-headings:

There's some great advice in here, and I'll certainly be reflecting on it with the organisations of which I'm part.

Source: opensource.com

Culture is the behaviour you reward and punish

This is an interesting read on team and organisational culture in practice. Interesting choice of image, too (I’ve used a different one).

In my mind, organisational culture is a lot like family dynamics, especially the parenting part. After all, kids follow what you do rather than what you say.Compensation helps very little when it comes to aligning culture, because it’s private. Public rewards are much more influential. Who gets promoted, or hangs out socially with the founders? Who gets the plum project, or a shout-out at the company all-hands? Who gets marginalized on low-value projects, or worse, fired? What earns or derails the job offer when interview panels debrief? These are powerful signals to our teammates, and they’re imprinting on every bit of it.

Culture eats strategy for breakfast, yet most organisations I've worked with and for don't spend nearly enough time on it.When role models are consistent, everyone gets the message, and they align towards that expectation even if it wasn’t a significant part of their values system before joining the company. That’s how culture gets reproduced, and how we assimilate new co-workers who don’t already possess our values.

People stop taking values seriously when the public rewards (and consequences) don’t match up. We can say that our culture requires treating each other with respect, but all too often, the openly rude high performer is privately disciplined, but keeps getting more and better projects. It doesn’t matter if you docked his bonus or yelled at him in private. When your team sees unkind people get ahead, they understand that the real culture is not one of kindness.

When you strip away everything else, all you've got are your principles and values. I think most organisations (and people) would do well to remember that.Culture is powerful. It makes teams highly functional and gives meaning to our work. It’s essential for organizational scale because culture enables people to make good decisions without a lot of oversight. But ironically, culture is particularly vulnerable when you are growing quickly. If newcomers get guidance from teammates and leaders who aren’t assimilated themselves, your company norms don’t have a chance to reproduce. If rewards like stretch projects and promotions are handed out through battlefield triage, there’s no consistency to your value system.

Source: Jocelyn Goldfein (via Offscreen Magazine)

Culture is the behaviour you reward and punish

This is an interesting read on team and organisational culture in practice. Interesting choice of image, too (I’ve used a different one).

In my mind, organisational culture is a lot like family dynamics, especially the parenting part. After all, kids follow what you do rather than what you say.Compensation helps very little when it comes to aligning culture, because it’s private. Public rewards are much more influential. Who gets promoted, or hangs out socially with the founders? Who gets the plum project, or a shout-out at the company all-hands? Who gets marginalized on low-value projects, or worse, fired? What earns or derails the job offer when interview panels debrief? These are powerful signals to our teammates, and they’re imprinting on every bit of it.

Culture eats strategy for breakfast, yet most organisations I've worked with and for don't spend nearly enough time on it.When role models are consistent, everyone gets the message, and they align towards that expectation even if it wasn’t a significant part of their values system before joining the company. That’s how culture gets reproduced, and how we assimilate new co-workers who don’t already possess our values.

People stop taking values seriously when the public rewards (and consequences) don’t match up. We can say that our culture requires treating each other with respect, but all too often, the openly rude high performer is privately disciplined, but keeps getting more and better projects. It doesn’t matter if you docked his bonus or yelled at him in private. When your team sees unkind people get ahead, they understand that the real culture is not one of kindness.

When you strip away everything else, all you've got are your principles and values. I think most organisations (and people) would do well to remember that.Culture is powerful. It makes teams highly functional and gives meaning to our work. It’s essential for organizational scale because culture enables people to make good decisions without a lot of oversight. But ironically, culture is particularly vulnerable when you are growing quickly. If newcomers get guidance from teammates and leaders who aren’t assimilated themselves, your company norms don’t have a chance to reproduce. If rewards like stretch projects and promotions are handed out through battlefield triage, there’s no consistency to your value system.

Source: Jocelyn Goldfein (via Offscreen Magazine)

Irony doesn't scale

Paul Ford is venerated in Silicon Valley and, based on what I’ve read of his, for good reason. He describes himself as a ‘reluctant capitalist’.

In this post from last year, he discusses building a positive organisational culture:

A lot of businesses, especially agencies, are sick systems. They make a cult of their “visionary” founders. And they keep going but never seem to thrive — they always need just one more lucky break before things improve. Payments are late. Projects are late. The phone rings all weekend. That’s not what we wanted to build. We wanted to thrive.He sets out characteristics of a 'well system':

Ford makes the important point that leaders need to be seen to do and say the right things:

I’m not a robot by any means. But I’ve learned to watch what I say. If there’s one rule that applies everywhere, it’s that Irony Doesn’t Scale. Jokes and asides can be taken out of context; witty complaints can be read as lack of enthusiasm. People are watching closely for clues to their future. Your dry little bon mot can be read as “He’s joking but maybe we are doomed!” You are always just one hilarious joke away from a sick system.It's a useful post, particuarly for anyone in a leadership position.

Source: Track Changes (via Offscreen newsletter /48)