- Reactionary neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, within an exclusionary vision of a racist, patriarchal, and homophobic society.

- Progressive neoliberalism — moving public goods into private hands, while using the banner of 'diversity' to assimilate equality and meritocracy.

What is ransom capitalism?

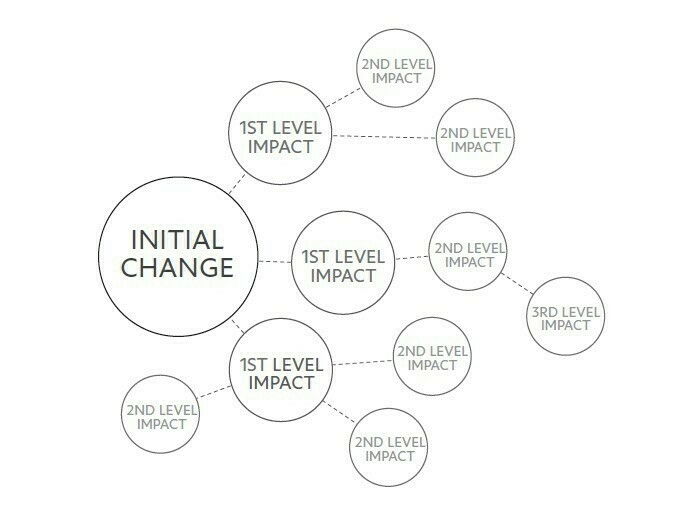

Gareth Fearn argues, and I absolutely agree, that governments are so captured by neoliberal thinking that some types of companies or sectors are seen as “too big to fail”. This leads to them being bailed out, which is a capitulation to a kind of ‘ransom capitalism’.

Bailouts are an ideal intervention for a decaying neoliberal politics: they maintain capital flows, rising asset prices and the upwards redistribution of wealth, while supporting the minimum needs of enough of the population to prevent total social breakdown.Source: Ransom Capitalism | London Review of BooksBritish politicians’ responses to soaring energy prices conform to the bailout consensus. Boris Johnson is promising ‘extra cash’, though leaving it up to his successor to work out the details (Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak have so far mostly offered tax cuts). Ed Davey, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, recently proposed an ‘energy furlough scheme’: the government would absorb the cost of rising energy prices and get some of the money back with a windfall tax. Labour soon followed suit, offering a similar cap to energy prices funded through some slightly more creative accounting.

In both cases, energy companies would receive large amounts of public money (at least £29 billion) to enable them to continue charging their customers sums that many cannot afford. With these proposals following so closely behind the pandemic bailouts, which had the backing of all UK parties, we can see there is broad support for such extraordinary interventions with very little thought being given to the causes of the crisis – beyond criticism of the outgoing prime minister’s personality.

[…]

There is an underlying assumption that at some point there will be a return to the ‘normality’ of self-regulating markets of private actors. But bailouts without structural change keep us on the path of ever-increasing losses for the public just to sustain the basics of life, while maintaining a failed market system which is not only generating crises but limiting responses to them – as many nations in the Global South have experienced for decades.

High inflation is not unique to the UK, but the capitulation to the energy companies’ ransom demands seems especially acute here, as is the actual rate of rising costs. France is able to lower prices through its state energy company, Spain and Germany have intervened to reduce the cost of public transport, and many of the proposed measures across Europe involve taking equity in energy companies or stricter regulation. But the UK is too far down the neoliberal rabbit-hole even to countenance such mild social democratic policies.

What is ransom capitalism?

Gareth Fearn argues, and I absolutely agree, that governments are so captured by neoliberal thinking that some types of companies or sectors are seen as “too big to fail”. This leads to them being bailed out, which is a capitulation to a kind of ‘ransom capitalism’.

Bailouts are an ideal intervention for a decaying neoliberal politics: they maintain capital flows, rising asset prices and the upwards redistribution of wealth, while supporting the minimum needs of enough of the population to prevent total social breakdown.Source: Ransom Capitalism | London Review of BooksBritish politicians’ responses to soaring energy prices conform to the bailout consensus. Boris Johnson is promising ‘extra cash’, though leaving it up to his successor to work out the details (Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak have so far mostly offered tax cuts). Ed Davey, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, recently proposed an ‘energy furlough scheme’: the government would absorb the cost of rising energy prices and get some of the money back with a windfall tax. Labour soon followed suit, offering a similar cap to energy prices funded through some slightly more creative accounting.

In both cases, energy companies would receive large amounts of public money (at least £29 billion) to enable them to continue charging their customers sums that many cannot afford. With these proposals following so closely behind the pandemic bailouts, which had the backing of all UK parties, we can see there is broad support for such extraordinary interventions with very little thought being given to the causes of the crisis – beyond criticism of the outgoing prime minister’s personality.

[…]

There is an underlying assumption that at some point there will be a return to the ‘normality’ of self-regulating markets of private actors. But bailouts without structural change keep us on the path of ever-increasing losses for the public just to sustain the basics of life, while maintaining a failed market system which is not only generating crises but limiting responses to them – as many nations in the Global South have experienced for decades.

High inflation is not unique to the UK, but the capitulation to the energy companies’ ransom demands seems especially acute here, as is the actual rate of rising costs. France is able to lower prices through its state energy company, Spain and Germany have intervened to reduce the cost of public transport, and many of the proposed measures across Europe involve taking equity in energy companies or stricter regulation. But the UK is too far down the neoliberal rabbit-hole even to countenance such mild social democratic policies.

Neoliberalism in any guise is not the solution but the problem

Today's quotation-as-title is from Nancy Fraser, whose short book The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born in turn gets its title from a quotation from Antonio Gramsci.

It's an excellent book; quick to read, straight to the point, and it helped me to understand some of what is going on at the moment in both US and world politics.

First, let's explain terms, as it is a book that presupposes some knowledge of political philosophy. 'Neoliberalism' isn't an easy term to define, as its meaning has mutated over time, and it's usually used in a derogatory way.

There's a whole history of the term at Wikipedia, but I'll use definitions from Investopedia and The Guardian:

Neoliberalism is a policy model—bridging politics, social studies, and economics—that seeks to transfer control of economic factors to the private sector from the public sector. It tends towards free-market capitalism and away from government spending, regulation, and public ownership.

Investopedia

In short, “neoliberalism” is not simply a name for pro-market policies, or for the compromises with finance capitalism made by failing social democratic parties. It is a name for a premise that, quietly, has come to regulate all we practise and believe: that competition is the only legitimate organising principle for human activity.

Guardian

To me, it's the reason why humans go out of their way to engineer situations where people and organisations are pitted against each other to compete for 'awards', no matter how made-up or paid-for they may be. It's a way of framing society, human interactions, and reducing everything to $$$.

In that vein, the most recent issue of New Philosopher, features an essay by Warwick Smith where he uses the thought experiment of an AI 'paperclip maximiser'. This runs amok and turns the entire universe into paperclips:

I recently heard Daniel Schmachtenberger taking this thought experiment in a very interesting direction by saying that human society is already the paperclip maximiser but instead of making paperclips we're making dollars — which are primarily just zeroes and ones in bank databases. Our collective intelligence system has on overriding purpose: to turn everything into money — trees, labour, water... everything. It is also very good at learning how to learn and is extremely good at eliminating any threats.

Warwick Smith

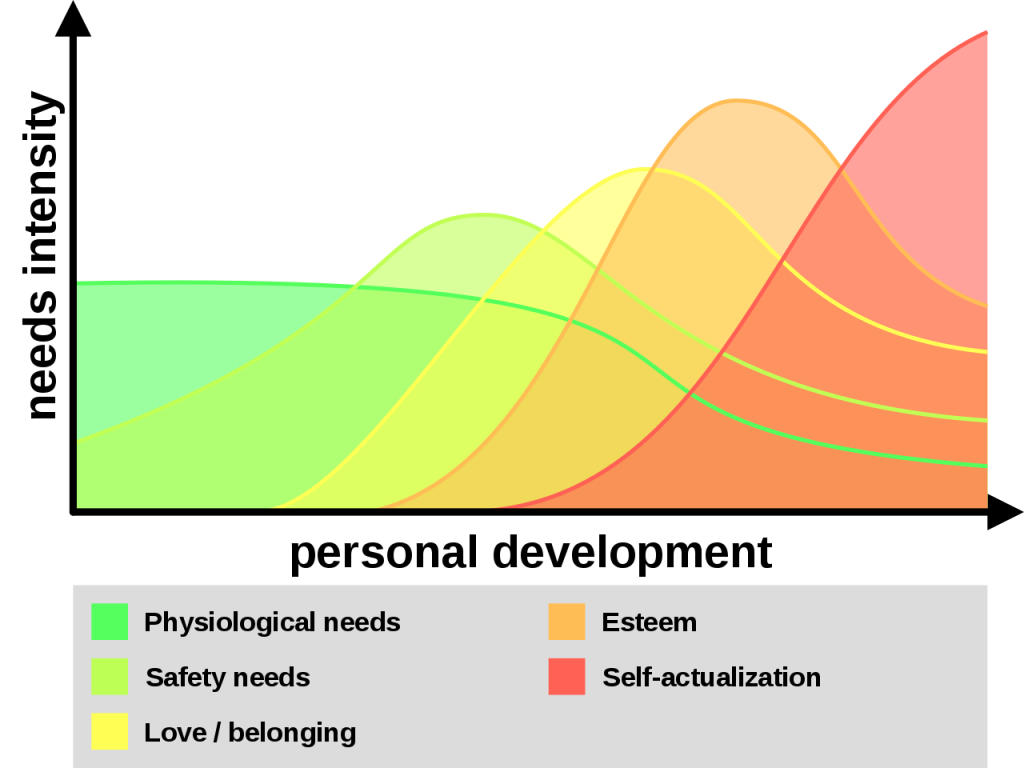

This attempt to turn everything into money is basically the neoliberal project. What Nancy Fraser does is identify two different strains of neoliberalism, which she explains through the lenses of 'distribution' and 'recognition':

The difference between these two strands of neoliberalism, then, comes in the way that they recognise people. Note that the method of distribution remains the same:

The political universe that Trump upended was highly restrictive. It was built around the opposition between two versions of neoliberalism, distinguished chiefly on an axis of recognition. Granted, one could choose between multiculturalism and ethnonationalism. But one was stuck, either way, with financialization and deindustrialization. With the menu limited to progressive and reactionary neoliberalism, there was no force to oppose the decimation of working-class and middle-class standards of living. Antineoliberal projects were severely marginalized, if not simply excluded from the public sphere.

Nancy Fraser

It's as if the Overton Window of acceptable public political discourse served up a menu of only different flavours of neoliberalism:

Ideologies are oriented within a narrative that spans the past, present, and future. We can argue over visions of what education should look like within a society, for example, because we're interested in how the next generation will turn out.

In Present Shock, Douglas Rushkoff explains that instead of shackling themselves to ideologies, Trump and other populist politicians take advantage of the 24/7 'always on' media landscape to provide a constant knee-jerk presentism:

A presentist mediascape may prevent the construction of false and misleading narratives by elites who mean us no good, but it also tends to leave everyone looking for direction and responding or overresponding to every bump in the road.

Douglas Rushkoff

What we're witnessing is essentially the end of politics as we know it, says Rushkoff:

As a result, what used to be called statecraft devolves into a constant struggle with crisis management. Leaders cannot get on top of issues, much less ahead of them, as they instead seek merely to respond to the emerging chaos in a way that makes them look authoritative.

[...]

If we have no destination toward we are progressing, then the only thing that motivates our movement is to get away from something threatening. We move from problem to problem, avoiding calamity as best we can, our worldview increasingly characterized by a sense of panic.

[...]

Blatant shock is the only surefire strategy for gaining viewers in the now.

Douglas Rushkoff

We might be witnessing the end of progressive neoliberalism, but it's not as if that's being replaced by anything different, anything better.

What, then, can we expect in the near term? Absent a secure hegemony, we face an unstable interregnum and the continuation of the political crisis. In this situation, the words of Gramsci ring true: "The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear."

Nancy Fraser

No matter what the question is, neoliberalism is never the answer. The trouble, I think, is that two-dimensional diagrams of political options are far too simplistic:

For example, as Edurne Scott Loinaz shows, even within the Libertarian Left (the 'lower left') there are many different positions:

The Libertarian Left has perhaps the best to offer in terms of fighting neoliberalism and populists like Trump. The problem is unity, and use of language:

When binary language is used within the lower left it does untold violence to our communities and makes solidarity impossible: if one can switch between binary language to speak truth about capitalists and authoritarians, and switch to dimensional language within the zone of solidarity with fellow lower leftists, it will be easier to nurture solidarity within the lower left.

Edurne Scott Loinaz

For the first time in my life, I'm actually somewhat fearful of what comes next, politically speaking. Are we going to end up with populists entrenching the authoritarian right, going back full circle to reactionary neoliberalism? Or does this current crisis mean that something new can emerge?

Header image by Guillaume Paumier used under a Creative Commons license

The endless Black Friday of the soul

This article by Ruth Whippman appears in the New York Times, so focuses on the US, but the main thrust is applicable on a global scale:

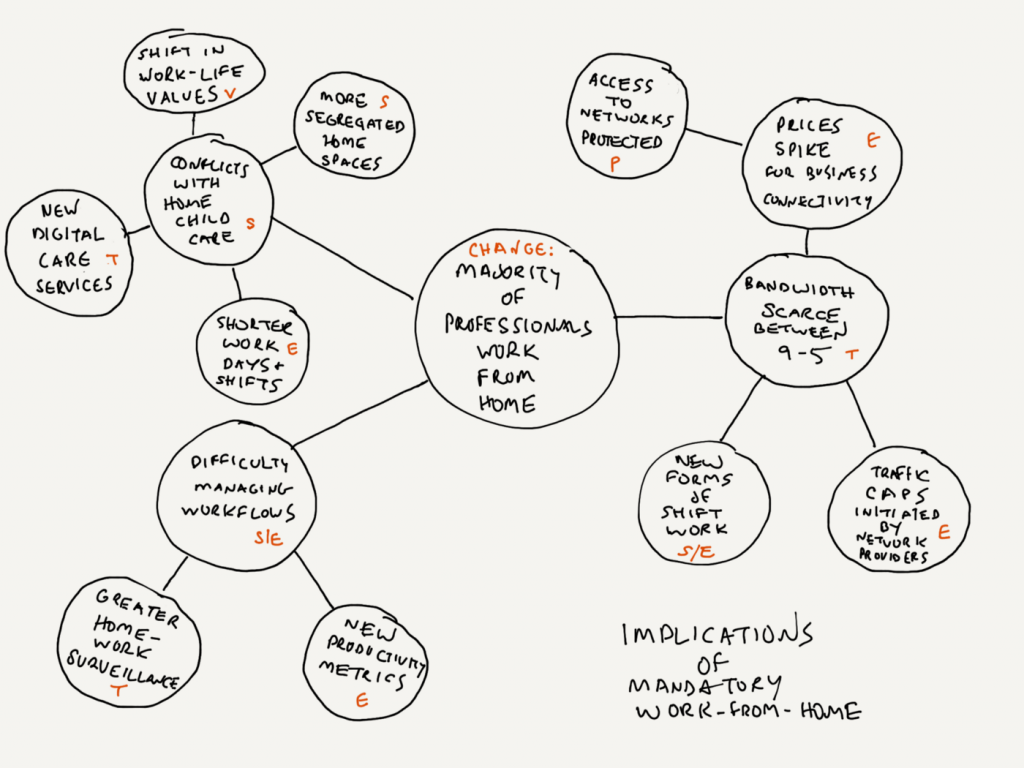

Apparently, 94% of the jobs created in the last decade are freelancer or contract positions. That's the trajectory we're on.When we think “gig economy,” we tend to picture an Uber driver or a TaskRabbit tasker rather than a lawyer or a doctor, but in reality, this scrappy economic model — grubbing around for work, all big dreams and bad health insurance — will soon catch up with the bulk of America’s middle class.

I don't think this is a neoliberal conspiracy, it's just the logic of capitalism seeping into every area of society. As we all jockey for position in the new-ish landscape of social media, everything becomes mediated by the market.Almost everyone I know now has some kind of hustle, whether job, hobby, or side or vanity project. Share my blog post, buy my book, click on my link, follow me on Instagram, visit my Etsy shop, donate to my Kickstarter, crowdfund my heart surgery. It’s as though we are all working in Walmart on an endless Black Friday of the soul.

[...]

Kudos to whichever neoliberal masterminds came up with this system. They sell this infinitely seductive torture to us as “flexible working” or “being the C.E.O. of You!” and we jump at it, salivating, because on its best days, the freelance life really can be all of that.

What I think’s missing from this piece, though, is a longer-term trend towards working less. We seem to be endlessly concerned about how the nature of work is changing rather than the huge opportunities for us to do more than waste away in bullshit jobs.

I’ve been advising anyone who’ll listen over the last few years that reducing the number of days you work has a greater impact on your happiness than earning more money. Once you reach a reasonable salary, there’s diminishing returns in any case.

Source: The New York Times (via Dense Discovery)

Is the gig economy the mass exploitation of millennials?

The answer is, “yes, probably”.

The 'sharing economy' and 'gig economy' are nothing of the sort. They're a problematic and highly disingenuous way for employers to not care about the people who create value in their business.If the living wage is a pay scale calculated to be that of an appropriate amount of money to pay a worker so they can live, how is it possible, in a legal or moral sense to pay someone less? We are witnessing a concerted effort to devalue labour, where the primary concern of business is profit, not the economic wellbeing of its employees.

The problem, of course, is late-stage capitalism:The employer washes their hands of the worker. Their immediate utility is the sole concern. From a profit point of view, absolutely we can appreciate the logic. However, we forget that the worker also exists as a member of society, and when business is allowed to use and exploit people in this manner, we endanger societal cohesiveness.

And the alternative? Co-operation.The neoliberal project has encouraged us to adopt a hyper-individualistic approach to life and work. For all the speak of teamwork, in this economy the individual reigns supreme and it is destroying young workers. The present system has become unfeasible. The neoliberal project needs to be reeled back in. The free market needs a firm hand because the invisible one has lost its grip.

Source: The Irish Times