Paying for everything twice

As someone who’s recently started using a budgeting app, and who has a lot of music-making equipment lying around unused, I concur.

One financial lesson they should teach in school is that most of the things we buy have to be paid for twice.Source: Everything Must Be Paid for Twice | RaptitudeThere’s the first price, usually paid in dollars, just to gain possession of the desired thing, whatever it is: a book, a budgeting app, a unicycle, a bundle of kale.

But then, in order to make use of the thing, you must also pay a second price. This is the effort and initiative required to gain its benefits, and it can be much higher than the first price.

A new novel, for example, might require twenty dollars for its first price—and ten hours of dedicated reading time for its second. Only once the second price is being paid do you see any return on the first one. Paying only the first price is about the same as throwing money in the garbage.

Likewise, after buying the budgeting app, you have to set it all up, and learn to use it habitually before it actually improves your financial life. With the unicycle, you have to endure the presumably painful beginner phase before you can cruise down the street. The kale must be de-veined, chopped, steamed, and chewed before it gives you any nourishment.

If you look around your home, you might notice many possessions for which you’ve paid the first price but not the second. Unused memberships, unread books, unplayed games, unknitted yarns.

Pix and digital payments in Brazil

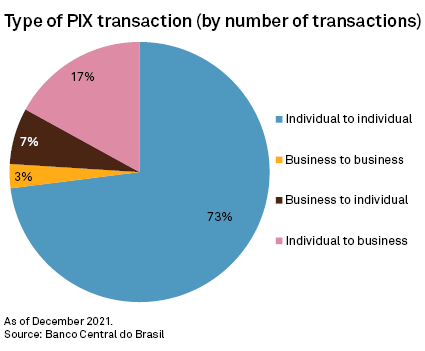

I came across this story via Benedict Evans' newsletter (it’s not the kind of thing I’d usually track). What I find interesting is this is a hugely successful rollout of a digital payments system done by a central bank. It’s helping real people, including those in poverty.

Meanwhile, crypto tokens are held by crypto bros and middle-class white guys like myself trying to make a quick buck. Just goes to show that innovation doesn’t always come from where you expect.

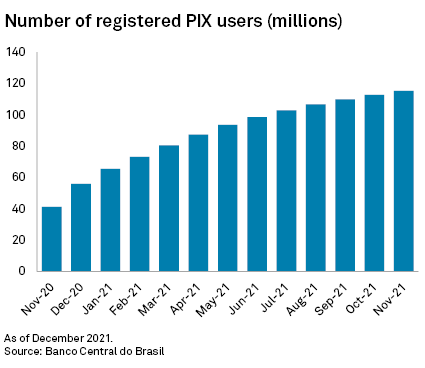

Source: Pix breaks ground in Brazil, shakes up payments market | S&P Global Market IntelligencePix, rolled out by the Banco Central do Brasil in Nov. 2020, was built for efficiency and financial inclusion. It now has 107.5 million registered accounts, more than half of the country’s population. One year after implementation, more than half a trillion Brazilian reais were transacted through the low-cost payments system last month. According to central bank data, Pix payments volume is already equivalent to 80% of debit and credit card transactions.

[…]

“Except for very particular transactions, market penetration tends to 99% on all individual transfers,” [Julian Colombo, CEO of banking technology firm N5] added. However, the rollout has not been without hiccups, including kidnapping.

[…]

On a recent Sunday in Rio de Janeiro, a three-member samba band played for a crowded restaurant. At the end, they passed around the tambourine to collect money. One diner apologized, saying he did not have any cash on him. The drummer said, “No problem, I take Pix,” and proceeded to share his code — which can be an email, phone number or other easy-to-remember code — with the diner, who promptly transferred the money his way.

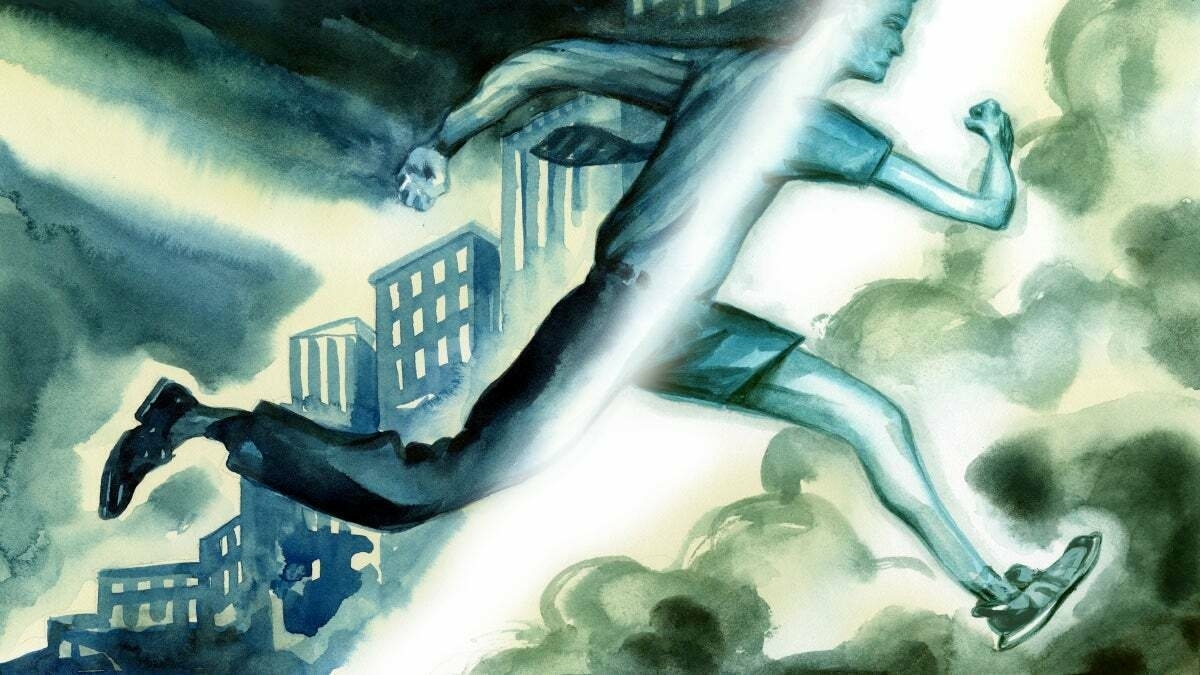

Middle class pursuit of pain through endurance sports is a thing

Oh this is fascinating. Get to your forties and everyone seems to be interested in marathons, triathlons, and putting on lycra to go and cycle somewhere.

This article explains that this is a function not only of access to the required time and money, but is a deep-seated need for those who are doing well out of the capitalist system.

Participating in endurance sports requires two main things: lots of time and money. Time because training, traveling, racing, recovery, and the inevitable hours one spends tinkering with gear accumulate—training just one hour per day, for example, adds up to more than two full weeks over the course of a year. And money because, well, our sports are not cheap: According to the New York Times, the total cost of running a marathon—arguably the least gear-intensive and costly of all endurance sports—can easily be north of $1,600.Source: Why Do Rich People Love Endurance Sports? - Outside Online[…]

There are a handful of obvious reasons the vast majority of endurance athletes are employed, educated, and financially secure. As stated, the ability to train and compete demands that one has time, money, access to facilities, and a safe space to practice, says William Bridel, a professor at the University of Calgary who studies the sociocultural aspects of sport. “The cost of equipment, race entry fees, and travel to events works to exclude lower socioeconomic status individuals,” he says, adding that those in a higher socioeconomic bracket tend to have nine-to-five jobs that provide some freedom to, for example, train before or after work or even at at lunch. “Almost all of the non-elite Ironman athletes who I’ve interviewed for my research had what would be considered white-collar jobs and commented on the flexibility this provided,” says Bridel.

[…]

Even so, there are myriad ways for relatively comfortable middle-to-upper-class individuals to spend their time and money. What is it about the voluntary suffering of endurance sports that attracts them?

This is a question sociologists are just beginning to unpack. One hypothesis is that endurance sports offer something that most modern-day knowledge economy jobs do not: the chance to pursue a clear and measurable goal with a direct line back to the work they have put in. In his book Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work, philosopher Matthew Crawford writes that “despite the proliferation of contrived metrics,” most knowledge economy jobs suffer from “a lack of objective standards.”

[…]

Another reason white-collar workers are flocking to endurance sports has to do with the sheer physicality involved. For a study published in the Journal of Consumer Research this past February, a group of international researchers set out to understand why people with desk jobs are attracted to grueling athletic events. They interviewed 26 Tough Mudder participants and read online forums dedicated to obstacle course racing. What emerged was a resounding theme: the pursuit of pain.

“By flooding the consciousness with gnawing unpleasantness, pain provides a temporary relief from the burdens of self-awareness,” write the researchers. “When leaving marks and wounds, pain helps consumers create the story of a fulfilled life. In a context of decreased physicality, [obstacle course races] play a major role in selling pain to the saturated selves of knowledge workers, who use pain as a way to simultaneously escape reflexivity and craft their life narrative.” The pursuit of pain has become so common among well-to-do endurance athletes that scientific articles have been written about what researchers are calling “white-collar rhabdomyolysis,” referring to a condition in which extreme exercise causes kidney damage.

Time millionaires

Same idea, new name: there’s nothing new about the idea of prioritising the amount of time and agency you have over the amount of money you make.

It’s just that, after the pandemic, more people have realised that chasing money is a fool’s errand. So, whatever you call it, putting your own wellbeing before the treadmill of work and career is always a smart move.

First named by the writer Nilanjana Roy in a 2016 column in the Financial Times, time millionaires measure their worth not in terms of financial capital, but according to the seconds, minutes and hours they claw back from employment for leisure and recreation. “Wealth can bring comfort and security in its wake,” says Roy. “But I wish we were taught to place as high a value on our time as we do on our bank accounts – because how you spend your hours and your days is how you spend your life.”Source: Time millionaires: meet the people pursuing the pleasure of leisure | The GuardianAnd the pandemic has created a new cohort of time millionaires. The UK and the US are currently in the grip of a workforce crisis. One recent survey found that more than 56% of unemployed people were not actively looking for a new job. Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that many people are not returning to their pre-pandemic jobs, or if they are, they are requesting to work from home, clawing back all those hours previously lost to commuting.

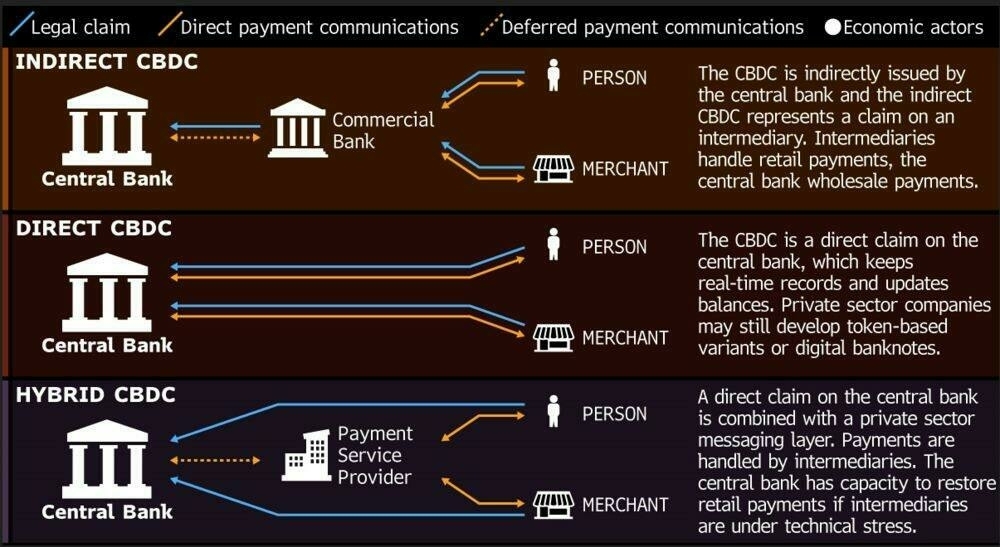

On the dangers of CBDCs

I can’t remember the last time I used cash. Or rather, I can (for my son’s haircut) because it was so unusual; it’s been about 18 months since my default wasn’t paying via the Google Pay app on my smartphone.

As a result, and because I also have played around with buying, selling, and holding cryptocurrencies, that a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) would be a benign thing. Sadly, as Edward Snowden explains, they really are not. His latest article is well worth a read in its entirety.

Rather, I will tell you what a CBDC is NOT—it is NOT, as Wikipedia might tell you, a digital dollar. After all, most dollars are already digital, existing not as something folded in your wallet, but as an entry in a bank’s database, faithfully requested and rendered beneath the glass of your phone.Source: Your Money and Your Life - by Edward Snowden - Continuing Ed — with Edward SnowdenNeither is a Central Bank Digital Currency a State-level embrace of cryptocurrency—at least not of cryptocurrency as pretty much everyone in the world who uses it currently understands it.

Instead, a CBDC is something closer to being a perversion of cryptocurrency, or at least of the founding principles and protocols of cryptocurrency—a cryptofascist currency, an evil twin entered into the ledgers on Opposite Day, expressly designed to deny its users the basic ownership of their money and to install the State at the mediating center of every transaction.

Leslie Caron on Cary Grant's attitude to money

I read most things online, but I came across this one via my print subscription to Guardian Weekly (which I recommend highly). Leslie Caron, who danced and acted with a host of big names, highlights Cary Grant’s attitude towards money.

I’ve always found Cary Grant fascinating, and in fact my online avatar used to be a photo of him. It seems, as Leslie Caron points out, that one’s mindset can be out of step with reality — which is a lesson to us all.

Who was her most talented leading man? “Cary Grant,” she answers immediately. In 1964, she starred with Grant in the romcom Father Goose; Grant was 27 years her senior. “Cary was a complicated brain,” she says, pointing to her head. “He was a remarkable performer. He was very instinctive, seductive, intelligent. But when he got mad he would get into a terrible state. He worried about money.” Surely he had plenty of it? Yes, she says, but when you grow up poor you always think like a poor person. “I remember Charlie Chaplin saying to me: ‘If I were rich …’” When Chaplin died in 1977, he left more than $100m to his fourth wife, Oona.Source: ‘I am very shy. It’s amazing I became a movie star’: Leslie Caron at 90 on love, art and addiction | The Guardian

'Prepper' philosophy

This morning, I came across a long web page from 2016, presumably created as a reaction to everything that went down that year (little did we know!)

Ostensibly, it's about preparing for scenarios in life that are relatively likely. It's pretty epic. While I've converted it to PDF and printed all 68 pages out to read in more detail, there were some parts that jumped out at me, which I'll share here.

[T]he purpose of this guide is to combat the mindset of learned helplessness by promoting simple, level-headed, personal preparedness techniques that are easy to implement, don't cost much, and will probably help you cope with whatever life throws your way.

lcamtuf, Doomsday Prepping For Less Crazy Folk

Growing up, my mother was the kind of woman who always had extra tins in the cupboards 'just in case'. Recently, my wife has taken this to the next level, with documents containing details on our stash including best before dates, etc.

Effective preparedness can be simple, but it has to be rooted in an honest and systematic review of the risks you are likely to face. Plenty of excited newcomers begin by shopping for ballistic vests and night vision goggles; they would be better served by grabbing a fire extinguisher, some bottled water, and then putting the rest of their money in a rainy-day fund.

LCAMTUF, DOOMSDAY PREPPING FOR LESS CRAZY FOLK

I see this document, which goes into money, self-defence, hygiene, and even relationships as neighbours as more of a philosophy of life.

Rational prepping is meant to give you confidence to go about your business, knowing that you are well-equipped to weather out adversities. But it should not be about convincing yourself that the collapse is just around the corner, and letting that thought consume and disrupt your life.

Stay positive: the world is probably not ending, and there is a good chance that it will be an even better place for our children than it is for us. But the universe is a harsh mistress, and there is only so much faith we should be putting in good fortune, in benevolent governments, or in the wonders of modern technology. So, always have a backup plan.

LCAMTUF, DOOMSDAY PREPPING FOR LESS CRAZY FOLK

Recommended reading 👍

(also check out the author's hyperinflation gallery)

At times, our strengths propel us so far forward we can no longer endure our weaknesses and perish from them

🤑 We can’t have billionaires and stop climate change

📹 How to make video calls almost as good as face-to-face

⏱️ How to encourage your team to launch an MVP first

☑️ Now you can enforce your privacy rights with a single browser tick

Quotation-as-title from Nietzsche. Image from top-linked post.

Face-to-face university classes during a pandemic? Why?

Earlier in my career, when I worked for Jisc, I was based at Northumbria University in Newcastle. It's just been announced that 770 students there have been infected with COVID-19.

As Lorna Finlayson, a philosophy lecturer at the University of Essex, points out, the desire to get students on campus for face-to-face teaching is driven by economics. Universities are businesses, and some of them are likely to fail this academic year.

[A]fter years of pushing to expand online learning and “lecture capture” on the basis that it is what students want, university managers have decided that what students really want now, during a global pandemic, is face-to-face contact. This sudden-onset fetish reached its most perverse extreme in the case of Boston University, which, realising that many teaching rooms lack good ventilation or even windows, decided to order “giant air circulators”, only to discover that the air circulators were very noisy. Apparently unable to source enough “mufflers” for the air circulators, the university ordered Bluetooth headsets to enable students and teachers to communicate over the roar of machinery.

All of which raises the question: why? The determination to bring students back to campus at any cost doesn’t stem from a dewy-eyed appreciation of in-person pedagogy, nor from concerns about the impact of isolation on students’ mental health. If university managers had any interest in such things, they would not have spent years cutting back on study skills support and counselling services.

Lorna Finlayson, How universities tricked students into returning to campus (The Guardian)

I know people who work in universities in various positions. What they tell me astounds me; a callous disregard for human life in the pursuit of either economic survival, or profit.

This is, as usual, all about the money. With student fees and rents now their main source of revenue, universities will do anything to recruit and retain. When the pandemic hit, university managers warned of a potentially catastrophic loss of income from international student fees in particular. Many used this as an excuse to cut jobs and freeze pay, even as vice-chancellors and senior management continued to rake in huge salaries. As it turned out, international student admissions reached a record high this year, with domestic undergraduate numbers also up – perhaps less due to the irresistibility of universities’ “offer” than to the lack of other options (needless to say, staff jobs and pay have yet to be reinstated).

Lorna Finlayson, How universities tricked students into returning to campus (The Guardian)

But students are more than just fee-payers. They are rent-payers too. Rightly or wrongly, most of those in charge of universities have assumed that only the promise of face-to-face classes would tempt students back to their accommodation. That promise can be safely broken only once rental contracts are signed and income streams flowing.

I predict legal action at some point in the near future.

The crisis in professional sport is one of its own making

I couldn't agree more with this analysis from Barney Ronay, one of my favourite sports writers:

Professional sport is facing a crisis of unprecedented urgency. It must be prepared to face it largely alone.

At which point it is worth being clear on exactly what is at stake. This is a moment of peril that should raise questions far beyond simply survival or sustaining the status quo. Questions such as: what is sport actually for? And more to the point, what do we want it to look like when this is all over?

It helps to define the terms of all this jeopardy. There has been a lot of emotive rhetoric about sport being on the verge of extinction, its very existence in doubt, as though the basic ability to participate, support and spectate could be vaporised out from beneath us.

This is incorrect. What is being menaced is the current financial management of professional sport, its existing models and cultural practices, much of which is pretty joyless and dysfunctional in the first place.

Barney Ronay, Never waste a crisis: Covid-19 trauma can force sport to change for good (The Guardian)

Was sport less enjoyable before loads of money was thrown at it? As Ronay points out, Gareth Bale earning £600,000 per week "could keep every club in League Two in business by paying their combined wage bill out of his annual salary".

I'm not sure the current model is sustainable, so if the pandemic forces a rethink, I'm all for it.

As scarce as truth is, the supply has always been in excess of demand

💬 Welcome to the Next Level of Bullshit

📚 The Best Self-Help Books of the 21st Century

💊 A radical prescription to make work fit for the future

👣 This desolate English path has killed more than 100 people

Quotation-as-title by Josh Billings. Image from top linked post.

What would you do if you were the richest man in the world? Now you can find out!

This is simultaneously amusing and horrifying:

A simple text-based adventure exploring the age-old question: What would you do if you had more money than any single human being should ever have?It's a text-based adventure game that gives you options as the richest man on earth, while educating you on how that money was amassed, and the scale of what would be possible with that kind of wealth.

Source: You Are Jeff Bezos

Reduce your costs, retain your focus

The older I get, the less important I realise things are that I deemed earlier in life. For example, the main thing in life seems to be to find something you can find interesting to work on for a long period of time. That’s unlikely to be a ‘job’ but more like a problem to be solved values to exemplify and share.

Jason Fried writes on his company’s blog about the journey that they’ve taken over the last 19 years. Everyone knows Basecamp because it’s been around for as long as you’ve been on the web.

What is true in business is true in your personal life. I'm writing this out in the garden of our terraced property. It's approximately the size of a postage stamp. No matter, it's big enough for what we need, and living here means my wife doesn't have to work (unless she wants to) and I'm not under pressure to earn some huge salary.2018 will be our 19th year in business. That means we’ve survived a couple of major downturns — 2001, and 2008, specifically. I’ve been asked how. It’s simple: It didn’t cost us much to stay in business. In 2001 we had 4 employees. We were competing against companies that had 40, 400, even 4000. We had 4. We made it through, many did not. In 2008 we had around 20. We had millions in revenue coming in, but we still didn’t spend money on marketing, and we still sublet a corner of someone else’s office. Business was amazing, but we continued to keep our costs low. Keeping a handle on your costs must be a habit, not an occasion. Diets don’t work, eating responsibly does.

These days we have huge expectations of what life should give us. The funny thing is that, if you stand back a moment and ask what you actually need, there's never been a time in history when the baseline that society provides has been so high.So keep your costs as low as possible. And it’s likely that true number is even lower than you think possible. That’s how you last through the leanest times. The leanest times are often the earliest times, when you don’t have customers yet, when you don’t have revenue yet. Why would you tank your odds of survival by spending money you don’t have on things you don’t need? Beats me, but people do it all the time. ALL THE TIME. Dreaming of all the amazing things you’ll do in year three doesn’t matter if you can’t get past year two.

We rush around the place trying to be like other people and organisations, when we need to think about what who and what we’re trying to be. The way to ‘win’ at life and business is to still be doing what you enjoy and deem important when everyone else has crashed and burned.

Source: Signal v. Noise

Wielding your pension fund for good

Some wise words in this article in The Guardian from Aditya Chakrabortty. Perhaps it’s my age, but I’m increasingly aware of the power that we have, collectively, around where and how we spend and save our money.

In big French companies, pension savers are offered the chance to invest 10% of their money in a fond solidaire, or solidarity fund, which supports unlisted social enterprises. In Britain, your average pension member doesn’t even get consulted on what values they’d like their money to support – whether fighting climate change or building social housing. Yet, rather than tackle those issues, the Labour party seeks to build a parallel finance system, in the form of a National Investment Bank, while other left economists talk about building a sovereign wealth fund, just as Norway has done with the proceeds of North Sea oil.I have several pensions (Teachers' Pension, Local Government, personal, Moodle…) and, as much as I’m able, I ensure that the money is being ethically invested. There’s so many frontiers on which we can change the world, not all of them are super-exciting…But we have a sovereign wealth fund already. It’s worth over £2tn and it’s called our pension funds. The big battle is to give us agency over our own savings, rather than leaving it all to some pinstriped manager on a fat commission.

Source: The Guardian

The role of Lady Luck

This post on Of Dollars and Data is a bit rambling, at least from my perspective, but I did like this paragraph:

I think this chimes well with Stoic philosophy: focus on the things within you control. There are going to be times in all of our lives when bad things happen. Conversely, there are going to be times when good things happen. We can't control anything apart from our reactions to these things.Think about the story you tell yourself about yourself. In all the lives you could be living, in all of the worlds you could simulate, how much did luck play a role in this one? Have you gotten more than your fair share? Have you had to deal with more struggles than most? I ask you this question because accepting luck as a primary determinant in your life is one of the most freeing ways to view the world. Why? Because when you realize the magnitude of happenstance and serendipity in your life, you can stop judging yourself on your outcomes and start focusing on your efforts. It’s the only thing you can control.

Source: Of Dollars and Data

The role of Lady Luck

This post on Of Dollars and Data is a bit rambling, at least from my perspective, but I did like this paragraph:

I think this chimes well with Stoic philosophy: focus on the things within you control. There are going to be times in all of our lives when bad things happen. Conversely, there are going to be times when good things happen. We can't control anything apart from our reactions to these things.Think about the story you tell yourself about yourself. In all the lives you could be living, in all of the worlds you could simulate, how much did luck play a role in this one? Have you gotten more than your fair share? Have you had to deal with more struggles than most? I ask you this question because accepting luck as a primary determinant in your life is one of the most freeing ways to view the world. Why? Because when you realize the magnitude of happenstance and serendipity in your life, you can stop judging yourself on your outcomes and start focusing on your efforts. It’s the only thing you can control.

Source: Of Dollars and Data

Multiple income streams

Right now, I’m splitting my time between being employed (four days per week with Moodle), my consultancy and the co-op which I co-founded (one day per week combined). In other words, I have more than one income stream, as this article suggests:

Having multiple income streams can come in handy if one income stream dries up. After two years in business, I've learned that you'll always have peaks and valleys. Sometimes everyone is paying you, and sometimes your lead pipeline can look barren. I started a marketing and PR agency and spent that first year working my startup muscles: planning, strategizing, defining markets. If I hit a slow month, I kept working those same exercises. While it helped grow my business, I sometimes needed an intellectual rest day.

People who have only ever been employed (which was me until three years ago!) wonder about the insecurity of consulting. But the truth is that every occupation these days is precarious — it's just hidden if you're employed.

This is a short article, but it's useful as both a call-to-action and to reinforce existing practices:Developing a secondary income stream is easier than you may think. Think about how you like to spend your off hours and research potential markets. Maybe you're really good at explaining something that is a difficult concept for other people--create a course on an on-demand training site like Udemy or Skillshare.

In general, we think more people are paying attention to us than they actually are. Your first endeavour doesn't have to set the world on fire, be a smash hit, or a bestseller. The important thing is to get out there and provide something that people want.

Through volunteering, putting myself out there, and developing my network, I haven't had to apply for a job since 2010. Also, with my consultancy, it's all inbound stuff. Some call it luck but, as Thomas Edison is quoted as saying:

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.I'd add that knowledge work doesn't look like work. But that's a whole other post.

Source: Inc.

Multiple income streams

Right now, I’m splitting my time between being employed (four days per week with Moodle), my consultancy and the co-op which I co-founded (one day per week combined). In other words, I have more than one income stream, as this article suggests:

Having multiple income streams can come in handy if one income stream dries up. After two years in business, I've learned that you'll always have peaks and valleys. Sometimes everyone is paying you, and sometimes your lead pipeline can look barren. I started a marketing and PR agency and spent that first year working my startup muscles: planning, strategizing, defining markets. If I hit a slow month, I kept working those same exercises. While it helped grow my business, I sometimes needed an intellectual rest day.

People who have only ever been employed (which was me until three years ago!) wonder about the insecurity of consulting. But the truth is that every occupation these days is precarious — it's just hidden if you're employed.

This is a short article, but it's useful as both a call-to-action and to reinforce existing practices:Developing a secondary income stream is easier than you may think. Think about how you like to spend your off hours and research potential markets. Maybe you're really good at explaining something that is a difficult concept for other people--create a course on an on-demand training site like Udemy or Skillshare.

In general, we think more people are paying attention to us than they actually are. Your first endeavour doesn't have to set the world on fire, be a smash hit, or a bestseller. The important thing is to get out there and provide something that people want.

Through volunteering, putting myself out there, and developing my network, I haven't had to apply for a job since 2010. Also, with my consultancy, it's all inbound stuff. Some call it luck but, as Thomas Edison is quoted as saying:

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.I'd add that knowledge work doesn't look like work. But that's a whole other post.

Source: Inc.

No cash, no freedom?

The ‘cashless’ society, eh?

Every time someone talks about getting rid of cash, they are talking about getting rid of your freedom. Every time they actually limit cash, they are limiting your freedom. It does not matter if the people doing it are wonderful Scandinavians or Hindu supremacist Indians, they are people who want to know and control what you do to an unprecedentedly fine-grained scale.Yep, just because someone cool is doing it doesn't mean it won't have bad consequences. In the rush to add technology to things, we create future dystopias.

Cash isn’t completely anonymous. There’s a reason why old fashioned crooks with huge cash flows had to money-launder: Governments are actually pretty good at saying, “Where’d you get that from?” and getting an explanation. Still, it offers freedom, and the poorer you are, the more freedom it offers. It also is very hard to track specifically, i.e., who made what purchase.It’s this bit that concerns me:Blockchains won’t be untaxable. The ones which truly are unbreakable will be made illegal; the ones that remain, well, it’s a ledger with every transaction on it, for goodness sakes.

We are creating a society where even much of what you say, will be knowable and indeed, may eventually be tracked and stored permanently.Source: Ian WelshIf you do not understand why this is not just bad, but terrible, I cannot explain it to you. You have some sort of mental impairment of imagination and ethics.