- Take a shower.

- Eat a nutritious meal.

- Take a walk outside (even if it’s literally to the corner and back).

- Do something — throw a ball, play tug of war, give belly rubs — with a dog. Just about any activity with my dogs, even if it’s just a snuggle on the couch for a few minutes, helps me.

- Do five minutes of yoga stretching.

- Listen to a guided meditation and follow along as best as you can.

Small sufferings

As I’ve mentioned sporadically for over a decade, I have a cold shower every morning. Not only is it good for mental health, but it’s a way of adding a small bit of suffering into my life.

That might sound like an odd thing to do, but study after study shows that it’s the difference between our experiences that provide pleasure or pain. Humans can adapt to anything, and I believe my days are better by starting them off with a small amount of suffering.

This post riffs on that idea, and as someone who’s no stranger to wild camping in the snow, I can definitely attest to daily cold showers being more effective than one-off trips for building resilience!

I suspect that small sufferings spread out across time are more helpful; that, for example, a 10 minute cold shower each day would make me feel more total gratitude for my cozy life than a one-week cold camping trip once per year – life is long and memory is short, so the cold trip would probably fade from memory after a week or two. But it's strangely hard to force myself to suffer, even if it's for my own good.Source: Optimal Suffering

Image: Unsplash

Therapy is simple

Craig Mod is a couple of months older than me, as I turn 43 just before Christmas. Like me, he’s gone through some therapy. Unlike me, he lives alone, and has continued therapy sessions for over five years.

What I like about the raw honesty of what he writes in this dispatch is how he wishes that everyone had access to therapy. Despite all of the positive messages about mental health, there’s still something of a stigma about getting some help. As if you should just “get over it”.

But therapy is part of how you become you. As Craig says, in the bit that comes after the part I’ve quoted below: “Therapy is simple. You load up FaceTime and speak out loud the things you’re most terrified about in life. Be radically open and honest, treating yourself as a third party, kindly observant without judgement."

It’s hard talking about your hopes, fears, and dreams with people you are emotionally invested in. There’s something remarkably grown-up and liberating about finally being able to start living a more flourishing life by sorting your shit out.

I’ve been thinking about aloneness recently. Well, I’ve been thinking about it my whole life. It’s difficult to remember a time where I didn’t feel alone or apart or “on my own.” And I’ve spent the majority of my adult life — from 17 onward — living mostly alone, going to bed alone, and waking up alone. Left to my own volition to somehow transmute that aloneness into forward momentum, “output,” (“content” ha ha) and positive habits.Source: Tokyo Walk, TBOT Cover, Aloneness | Roden Issue 086[…]

I just turned 43 the other day. As part of the fun of embracing mid-life crises, I’m in pattern matching mode. Two decades of watching friends either pair up and start families (or just embark on paired adventures), or continue down paths of aloneness. It seems to get more and more acute — the effects of aloneness — as folks drift into their 40s. It also seems to be more and more difficult to break habits connected with aloneness the older we get. This makes sense. Habits self-reinforce. And the folks with families have less time for solo people, creating even more dissonance.

[…]

I’ve spent the last five and half years speaking weekly with a therapist in New York over FaceTime. I started because I was exhausted. I recognized toxic relationship patterns that I had held onto since my teenage years, and wanted to break free. And I recognized that I had spent roughly twenty years not being able to do that on my own. (I had made some strides, of course, in fits and starts; most notably when I was 27, then: at the lowest of lows, I began running in the middle of the night (2am, feeling like I was losing my mind, put on my shoes, and ran the silent moonlit summer streets of Tokyo until my lungs burned and I felt back on the ground), soon completing two full marathons, felt my sense of value and self-worth rise, charged more for my time, made my way to Palo Alto, worked with incredible talent, made real money, big projects, huge scale, proved to myself I wasn’t stuck — it was an incredible stretch, thinking back on it now, a stretch of life-transformational love and hugs and sense of support, all initially catalyzed by feeling more alone than ever before, a yawning endless aloneness, and wanting to crawl out of that well before someone came and sealed the top.) Back to five years ago — I was 37 and stuck and thought — OK, let’s try something new. Hence: calling in for support (finally!).

I feel guilty for having access to this therapist. I want everyone to have access to someone like this. The world would be whole if you gave everyone a talented therapist and a cat. I can’t overstate how transformational my weekly act of analysis has been. I am still broken in many obvious (and non-unique) ways. But through these weekly sessions I’ve mitigated a huge chunk of lingering aloneness.

Treating depression with hot yoga

Although I don’t think he went for the reasons given in this article, my late, great friend Dai Barnes used to love hot yoga. In fact, living as a teacher on-site at a boarding school, he’d travel miles to go to his nearest venue.

This Harvard Gazette article suggests that hot yoga might help with depression. I can definitely understand that: I’ve just re-added the spa to my leisure centre membership, and even just going in the sauna at this time of year feels incredible.

In a randomized controlled clinical trial of adults with moderate-to-severe depression, those who participated in heated yoga sessions experienced significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared with a control group.Source: Heated yoga may reduce depression in adults | Harvard Gazette[…]

In the eight-week trial, 80 participants were randomized into two groups: one that received 90-minute sessions of Bikram yoga practiced in a 105°F room and a second group that was placed on a waitlist (waitlist participants completed the yoga intervention after their waitlist period). A total of 33 participants in the yoga group and 32 in the waitlist group were included in the analysis.

[…]

After eight weeks, yoga participants had a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms than waitlisted participants, as assessed through what’s known as the clinician-rated Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-CR) scale.

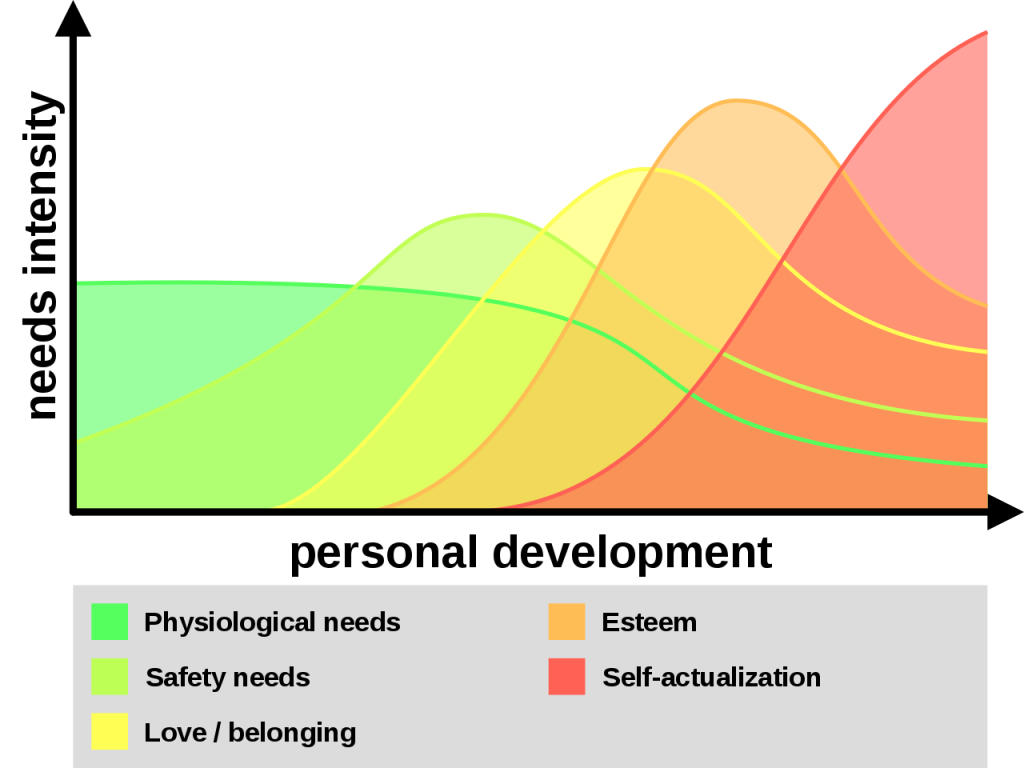

Microcast #101 — Self-esteem, pies, and moving house

More solo waffle about various things. I could pretend there's a consistent thread, but then I'd be lying.

Show notes

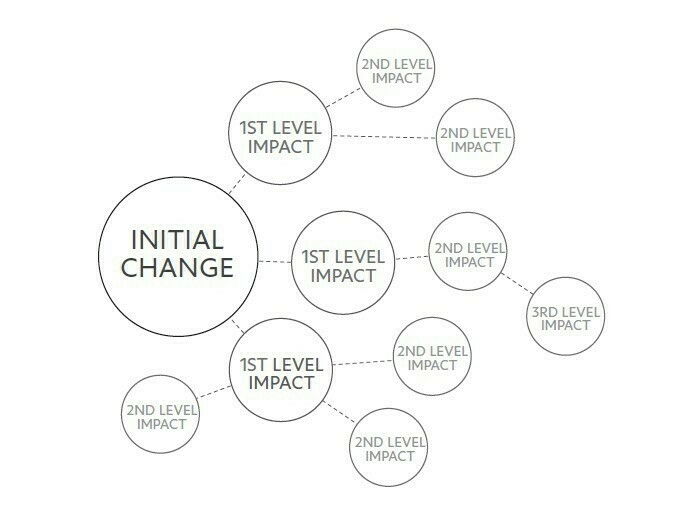

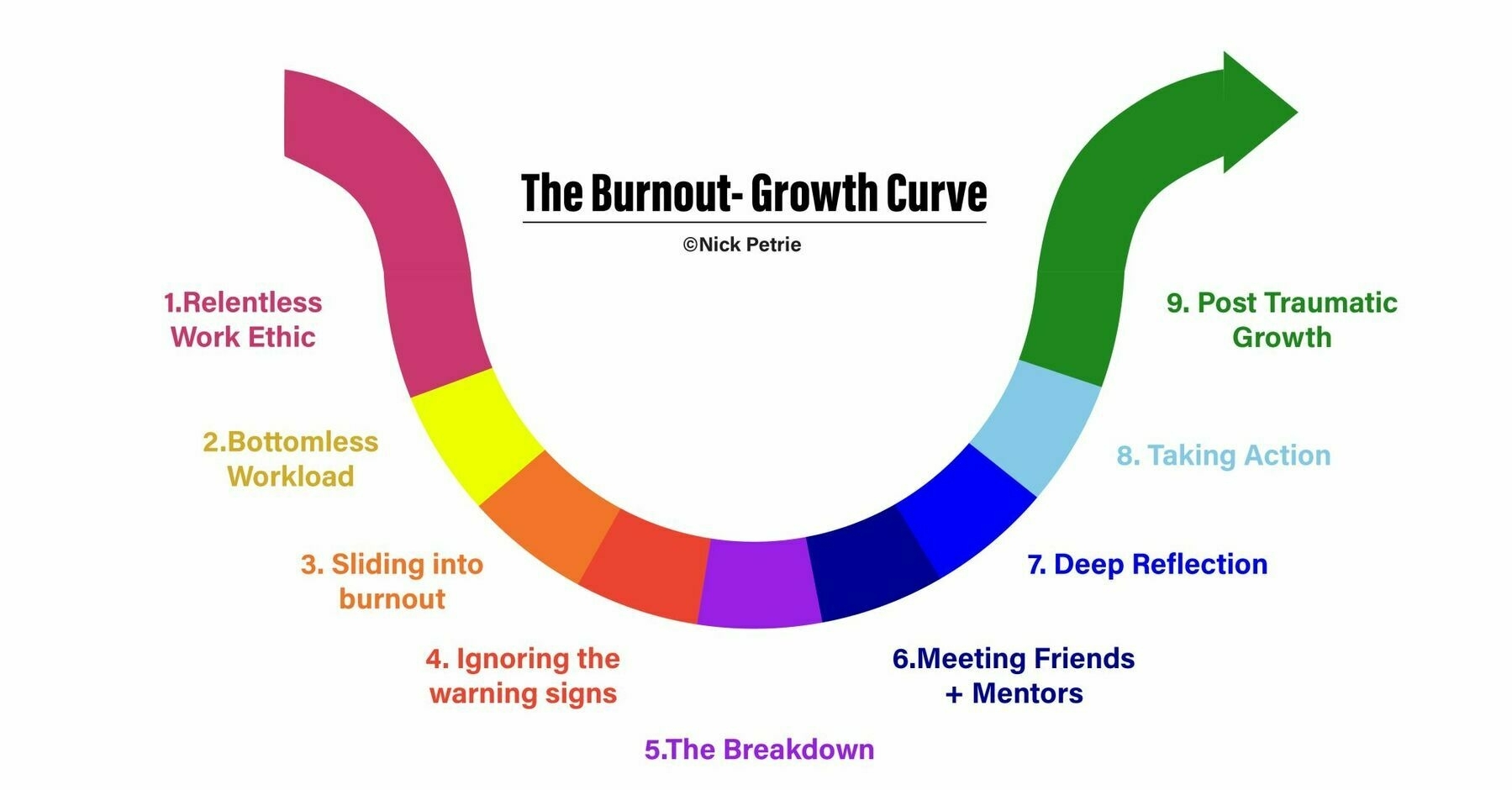

The burnout curve

I stumbled across this on LinkedIn. There doesn't seem to be an authoritative source yet other than the author's (Nick Petrie) social media posts, which is a shame. So I'm quoting most of it here so I can find and refer to it in future.

In terms of my own experience, I slid down that slope pretty quickly in my teaching career, and definitely experienced the 'trap' of going back into a similar situation in a different school. It was also toxic as I had been promoted quickly and, looking back, probably beyond my abilities and experience at the time.

But the great thing about this graphic is that it shows that it's possible to dig your way out, as I did, by realising that a different path is possible. It hasn't always been plain sailing, and there have been other, lesser, traumas since. But I've definitely grown from my earlier experiences, and this is a handy chart to show people who are near the bottom of the curve.

When we interviewed people who had burned out, they told us remarkably similar stories.1. A relentless work ethic – they had a set of beliefs and stories that drove them to work hard - I will deliver, I won’t let people down, I must give 100% at all times.2. Bottomless workload – they joined organizations that rewarded their work ethic with endless work. The harder they worked the more they were given.3. Sliding into burnout – thoughts of work became constant. They had trouble switching off in the evenings, work was taking over their life.4. Ignoring the warning signs – their body was sending signals that something needed to change. They were tense, irritated, exhausted. But they couldn’t slow down – there was too much to do.5. The breakdown – For those who would not listen, the body and brain had a last resort. They shut down. People couldn’t get out of bed, couldn’t drive, couldn’t read. The body refused to go on.The trap for many people is the belief that rest is the solution. So, they took a break – a week, a month or a year. They then went back to the same work, with the same mindset and the same behaviors. They got the same result.The people we interviewed who genuinely overcame burnout followed a common path.6. Meeting friends and mentors – they realized they couldn’t repeat their past. They needed new perspectives and a new approach. They got these from family, peers, coaches, therapists and support groups.7. Deep reflection – they came off autopilot for the first time in years. They reflected deeply on the past – what caused me to burnout? What was driving me? Then the future – what sort of work and life do I want going forward? How can I move myself towards this vision?8. Taking action – they took new actions, sometimes big – change of job, change of career - sometimes small - they set new boundaries, restarted a hobby, got a therapist. Some things helped, some things did not. It didn’t matter. The key thing was they were doing NEW things. They were not repeating their old habits. New actions led to new insights and habits.9. Post traumatic growth – when we interviewed people who took this path 2 years after their burnout, the most surprising thing was how much they had grown from the experience.

Source: Nick Petrie | LinkedIn

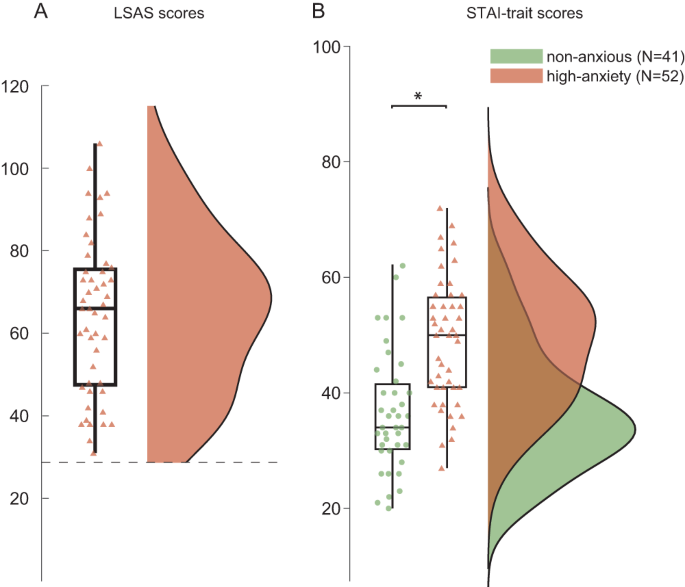

Why anxious people find it difficult to control their emotions

This explains a lot. Basically, studies have found that a specific part of the brain behaves differently in anxious individuals, and this difference might explain why they struggle with emotional control. It’s like a traffic jam in the brain that makes it harder for the signals to get through, leading to difficulties in managing emotional reactions.

Anxious individuals consistently fail in controlling emotional behavior, leading to excessive avoidance, a trait that prevents learning through exposure. Although the origin of this failure is unclear, one candidate system involves control of emotional actions, coordinated through lateral frontopolar cortex (FPl) via amygdala and sensorimotor connections. Using structural, functional, and neurochemical evidence, we show how FPl-based emotional action control fails in highly-anxious individuals. Their FPl is overexcitable, as indexed by GABA/glutamate ratio at rest, and receives stronger amygdalofugal projections than non-anxious male participants. Yet, high-anxious individuals fail to recruit FPl during emotional action control, relying instead on dorsolateral and medial prefrontal areas. This functional anatomical shift is proportional to FPl excitability and amygdalofugal projections strength. The findings characterize circuit-level vulnerabilities in anxious individuals, showing that even mild emotional challenges can saturate FPl neural range, leading to a neural bottleneck in the control of emotional action tendencies.Source: Anxious individuals shift emotion control from lateral frontal pole to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Nature Communications

Actions speak louder than words

This article popped up on my feeds a couple of weeks ago and I recognised the organisation behind the website. Having listened to an excellent Art of Manliness podcast episode featuring Dr John Barry, I knew that ‘The Centre for Male Psychology’ is actually legit.

What this article discusses I’ve found true in my own life. I am by temperament introspective, which means for many years I thought the answer to any form of melancholy came in thinking. But, actually, I’ve found the answer to be in action in doing things such as climbing mountains, running, and doing things with my hands.

The two ways of regulating emotions have implications for the field of mental health, which relies predominately on talking therapy – in particular talking about feelings. Does this not suggest that there could be, and perhaps needs to be, more emphasis on discussing the therapeutic value of action? It may not be practical to conduct therapy while engaged in physical activity such as a gym workout or while out walking in the streets, but the therapeutic discussion can at least focus more on the “doing” aspects of a man’s life. For example a therapist might ask how did problem XYZ make a man act out, along with exploring which physical activities or responses might help him to modulate such emotions more optimally in future. Does riding a Jet Ski, or going for a jog, or building some wooden furniture make him feel better or worse? Does that difficult manoeuvre in the video game remind of difficulties in his relationship with his girlfriend? Does the same video game provide some optimism that if he can get past the difficult manoeuvre within the game then perhaps he can find a way around the impasse with his girlfriend? Activities like these provide a symbolic canvas on which men project, and then work through various scenarios of real life, with potential to shift affective resonances in the process.Source: Men tend to regulate their emotions through actions rather than words | The Centre for Male PsychologyWhen a man talks about how he operated a lathe, did some welding, restored a bit of discarded and broken furniture, might he be sharing a strategy of how he successfully redirected suicidal feelings? Perhaps we should not be so quick to shut down these conversations with accusations of being work obsessed, effectively stymieing natural male expressions with injunctions to talk less about activities and to communicate more effusively with feelings words. For many men, activities are the preferred canvases on which they can process feelings and carve out some genuine psychological equilibrium.

This is probably a reason why men talk so much about work, sports, building things, computer games, recreational activities – it may be their preferred way of communicating the ways they wrestle with psychological issues. Sadly, the therapeutic industry is quick to chastise men’s preference for intelligent actions, conflating them with pathological reflexes such as unconscious acts of aggression, dependence on drugs and booze, and other destructive versions of so-called “acting-out” as they are so often branded.

You can‘t ruminate and listen at the same time

David Cain at Raptitude has a post which is somewhat bizarrely entitled 10 Things I Want to Communicate to the Human Species Before I Die. The first point is about shopping trolleys, so I’m not sure how tongue-in-cheek it all is.

Anyway, without saying whether I agree or disagree with any of the other statements, I want to draw attention to the last one. Ruminating is a complete waste of time, and as someone susceptible to it I want to +1 the advice to get out of your head and listen if you’re succumbing to it.

For me, that often means listening to my iPod in the early hours of the morning while lying sleepless in bed. But it can mean listening to other people, or just your surroundings.

The tendency of the modern human is to live in their head — almost perpetually monologuing and forecasting and rehashing. This is a seldom-helpful habit most of us reinforce constantly by tumbling along with its momentum. You can weaken the grip of the ruminative mind by frequently taking a few seconds to be quiet and listen to your surroundings. Doing this reveals something interesting: when you actively use your attention for listening (or in any other intentional way) it cannot be used for more rumination. Each time you do this, the gravity of the monologuing mind weakens. If even a fraction of the population learned how to perforate their ongoing ruminative thought-mill like this, it might be a different world.Source: 10 Things I Want to Communicate to the Human Species Before I Die | Raptitude

Study shows no link between age at getting first smartphone and mental health issues

Where we live is unusual for the UK: we have first, middle, and high schools. The knock-on effect of this in the 21st century is that kids aged nine years old are walking to school and, often, taking a smartphone with them.

This study shows that the average age children were given a phone by parents was 11.6 years old, which meshes with the ‘norm’ (I would argue) in the UK of giving kids one when they go to secondary school.

What I like about these findings are that parents overall seem to do a pretty good job. It’s been a constant battle with our eldest, who is almost 16, to be honest, but I think he’s developed some useful habits around technology.

Parents fretting over when to get their children a cell phone can take heart: A rigorous new study from Stanford Medicine did not find a meaningful association between the age at which kids received their first phones and their well-being, as measured by grades, sleep habits and depression symptoms.Source: Age that kids acquire mobile phones not linked to well-being, says Stanford Medicine study | Stanford Medicine[…]

The research team followed a group of low-income Latino children in Northern California as part of a larger project aimed to prevent childhood obesity. Little prior research has focused on technology acquisition in non-white or low-income populations, the researchers said.

The average age at which children received their first phones was 11.6 years old, with phone acquisition climbing steeply between 10.7 and 12.5 years of age, a period during which half of the children acquired their first phones. According to the researchers, the results may suggest that each family timed the decision to what they thought was best for their child.

“One possible explanation for these results is that parents are doing a good job matching their decisions to give their kids phones to their child’s and family’s needs,” Robinson said. “These results should be seen as empowering parents to do what they think is right for their family.”

Some tips for adding winter cheer

There are some excellent suggestions in this list of 53 things that can give you a lift over the winter months. I’ve highlighted three of my favourites below!

7. Walk with an audio book On a crisp winter’s day, there is no finer companion than 82-year-old actor Seán Barrett. His sublime narration of Mick Herron’s Slough House series, about a bunch of MI5 outcasts, will bring cheer to the gloomiest days.Source: Need a lift? Here’s 53 easy ways to add cheer to your life as winter looms | The Guardian[…]

18. Buy foods you can’t identify Purchase food in shops where the majority of products have no English on the packaging, so eating what you buy is an adventure. It might be black limes, a box of tamarinds or a rosewater drink with vermicelli pieces. It’s like travelling without travelling.

[…]

50. Sweat in a sauna We’ve all been told about the wellbeing boost of plunging into cold water, wild swimming and turning your shower down to freezing. But who wants to be cold? Book yourself into a sauna. Let the heat and steam soak deep into your bones and sweat out all your worries.

Being 'quietly fired' at work

I’ll not name the employer, and this wasn’t recent, but I’ve been ‘quietly fired’ from a job before. I never really knew why, other than a conflict of personalities, but there was no particular need for pursuing that path (instead of having a grown-up conversation) and it definitely had an impact on my mental health.

I think part of the reason this happens is because a lot of organisations have extremely poor HR functions and managers without much training. As a result, they muddle through, avoiding conflict, and causing more problems as a result.

There may not always be a good fit between jobs and the workers hired to do them. In these cases, companies and bosses may decide they want the worker to depart. Some may go through formal channels to show employees the door, but others may do what Eliza’s boss did – behave in such a way that the employee chooses to walk away. Methods may vary; bosses may marginalise workers, make their lives difficult or even set them up to fail. This can take place over weeks, but also months and years. Either way, the objective is the same: to show the worker they don’t have a future with the company and encourage them to leave.Source: The bosses who silently nudge out workers | BBC WorklifeIn overt cases, this is known as ‘constructive dismissal’: when an employee is forced to leave because the employer created a hostile work environment. The more subtle phenomenon of nudging employees slowly but surely out of the door has recently been dubbed ‘quiet firing’ (the apparent flipside to ‘quiet quitting’, where employees do their job, but no more). Rather than lay off workers, employers choose to be indirect and avoid conflict. But in doing so, they often unintentionally create even greater harm.

[…]

An employee subtly nudged out the door isn’t without legal recourse, either. “If you were to look at each individual aspect of quiet firing, there’s likely nothing serious enough to prove an employer breach of contract,” says Horne. “However, there’s the last-straw doctrine: one final act by the employer which, when added together with past behaviours, can be asserted as constructive dismissal by the employee.”

More immediate though, is the mental-health cost to the worker deemed to be expendable by the employer – but who is never directly informed. “The psychological toll of quiet firing creates a sense of rejection and of being an outcast from their work group. That can have a huge negative impact on a person’s wellbeing,” says Kayes.

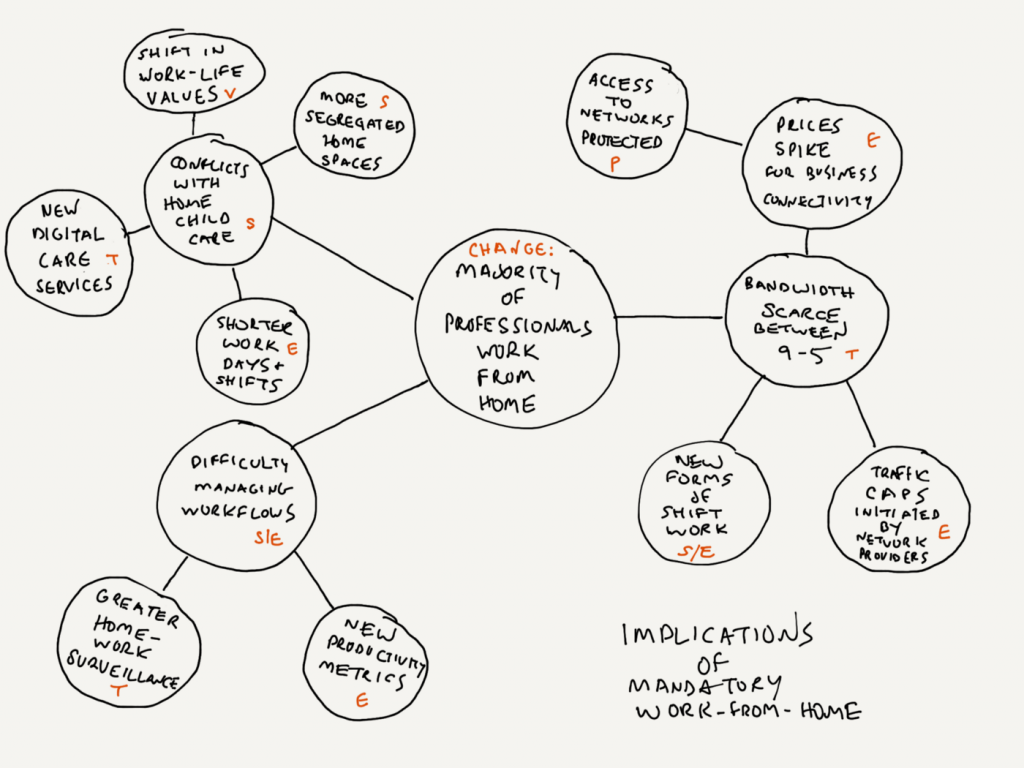

Why go back to normal when you weren't enjoying it in the first place?

Writing in Men's Health, and sadly not available anywhere I can link to, Will Self reflects on what we've collectively learned during the pandemic.

In it, he uses a quotation from Nietzsche I can't seem to find elsewhere, "There are better things to be than the merely productive man". I definitely feel this.

[T]he mood-music in recent months from government and media has all been about getting back to normal. So-called freedom. Trouble is... people from all walks of life and communities [have] expressed a reluctance to resume the lifestyle they were enjoying before March of last year. Quite possibly this is because they weren't really enjoying that much in the first place — and it's this that's been exposed by the pandemic and its associated measures.

The difficulty, I think, is that lots of people (me included at times) had pre-pandemic lives that they would probably rate a 6/10. Not terrible enough for the situation by itself to be a stimulus for change. But not, after a break, the thought of returning to how things were sounds... unappetising.

We all know the unpleasant spinning-in-the-hamster-wheel sensation that comes when we're working all hours with the sole objective of not having to work all hours — it traps us in a moment that's defined entirely by stress-repeating-anxiety, a feeling that mutates all too easily into full-blown depression. And we're not longer the sort of dualists who believe that psychological problems have no bodily correlate — on the contrary, we all understand that working too hard while feeling that work to be valueless can take us all the way from indigestion to an infarct.

I've burned out a couple of times in my life, which is why these days I feel privileged to be able to work 25-hour weeks by choice. There's more to life than looking (and feeling!) "successful".

It's funny, I have more agency and autonomy than most people I know, yet I increasingly resent the fact that this is dependent upon some of the very technologies I've come to realise are so problematic for society.

[I]t might be nice in the way of 18 months of being told what to do, to feel one was telling one's self what to do. One way of conceptualising the renunciation necessary to cope with the transition from a lifestyle where everything can be bought to one in which both security and satisfaction depend on more abstract processes, is to critique not just the unhealthy economy but the pathological dependency on technology that is its sequel.

Ultimately, I think Will Self does a good job of walking a tightrope in this article in not explicitly mentioning politics. The financial crash, followed by austerity, Brexit, and now the pandemic, have combined to hollow out the country in which I live.

The metaphor of a pause button has been overused during the pandemic. That's for a reason: most of us have had an opportunity, some for the first time in their lives, to stop and think what we're doing — individually and collectively.

What comes next is going to be interesting.

Not a sponsored mention by any means, but just a heads-up that I read this article thanks to my wife's Readly subscription. It's a similar monthly price to Netflix, but for all-you-can-read magazines and newspapers!

Fall Regression

I’ve only just discovered the writing of Anne Helen Petersen, via one of the many newsletters and feeds to which I subscribe. I featured her work last week about remote working.

Petersen’s newsletter is called Culture Study and the issue that went out yesterday was incredible. She talks about this time of year — a time I struggle with in particular — and gets right to the heart of the issue.

I’ve learned to take Vitamin D, turn on my SAD light, and to go easy on myself. But there’s always a little voice suggesting that this is how it’s going to be from here on out. So it’s good to hear what other people advise. For Petersen, it’s community involvement.

A teacher recently told me that there’s a rule in her department: no major life decisions in October. The same holds true, she said, for March. But March is well-known for its cruelty. I didn’t realize it was the same for October, even though it makes perfect sense: the charge of September, those first golden days of Fall, the thrill of wearing sweaters for the first time, those are gone. Soon it’ll be Daylight Savings, which always feels like having the wind knocked out of the day. People in high elevations are already showing off their first blasts of snow. We have months, months, to go.Source: What’s That Feeling? Oh, It’s Fall Regression | Culture StudyAs distractions fade, you’re forced to sit with your own story of how things are going. Maybe you’d been bullshitting yourself for weeks, for months. It was easy to ignore my bad lunch habits when I was spending most of the day outside. Now it’s just me and my angry stomach and scraping the tub of the hummus container yet again. Or, more seriously: now it’s just me swimming against the familiar tide of burnout, not realizing how far it had already pulled me from shore.

[…]

Is this the part of the pandemic when we’re happy? When we’re angry? When we’re hanging out or pulling back, when we’re hopeful or dismayed, when we’re making plans or canceling them? The calendar moves forward but we’re stuck. In old patterns, in old understandings of how work and our families and the world should be. That’s the feeling of regression, I think. It’s not that we’re losing ground. It’s that we were too hopeful about having gained it.

Health and sanity before profit

This is an interesting article that takes the tennis player Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open as a symptom of wider trends in the workplace.

Many Americans have experienced burnout, and its adjacent phenomenon, languishing, during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, it has hit women, especially mothers, particularly hard and women’s professional ambition has suffered, according to a survey by CNBC/SurveyMonkey. This trend might be read as a grim step backward in the march toward gender egalitarianism. Or, as in some of the criticism of Ms. Osaka, as an indictment of younger generations’ work ethic. Either interpretation would be misguided.Source: Naomi Osaka and the Cost of Ambition | The New York TimesA better way of putting it: Ms. Osaka has given a public face to a growing, and long overdue, revolt. Like so many other women, the tennis prodigy has recognized that she has the right to put her health and sanity above the unending demands imposed by those who stand to profit from her labors. In doing so, Ms. Osaka exposes a foundational lie in how high-achieving women are taught to view their careers.

In a society that prizes individual achievement above most other things, ambition is often framed as an unambiguous virtue, akin to hard work or tenacity. But the pursuit of power and influence is, to some extent, a vote of confidence in the profit-driven myth of meritocracy that has betrayed millions of American women through the course of the pandemic and before it, to our disillusionment and despair.

How to recover from burnout

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines occupational burnout as "feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and reduced professional efficacy."

Based on that definition, I've experienced burnout twice, once in my twenties and once in my thirties. But what to do about it? And how can we prevent it?

I read a lot of Hacker News, including some of the 'Ask HN' threads. This one soliciting advice about burnout received what I considered to be a great response from one user.

Around August last year I just couldn't continue. I wasn't sleeping, I was frequently run down, and I was self-medicating more and more with drugs and alcohol. It eventually got to the point where simply opening my laptop would elicit a fight or flight response.

I was lucky enough to be in a secure enough financial situation to largely take 6 months off. If you're in a position to do this, I highly recommend it.

I uninstalled gmail, slack, etc. from my phone. I considered getting a dumb phone, but settled for turning off push notifications for everything instead. I went away with my girlfriend for a week and left all my tech at home except for my kindle (literally the first time I've been disconnected for more than a couple of days in probably 20 years). I exercised as much as possible and spent time in nature going for walks, etc.

I've been back at it part time for the last few months. Gradually I felt the feelings of burnout being replaced with feelings of boredom, which is hopefully my brain's way of saying that it's starting to repair itself and ready to slowly return to work.

I'm still nowhere near back to peak productivity, but I'm starting to come to terms with the fact that I may never get back there. I'm 36 and probably would have dropped dead of overwork by 50 if I kept up the tempo of the last 10 years anyway.

I'm not 'cured' by any means, but I believe things are slowly getting better.

My advice to you is to be kind and patient with yourself. Try not to stress about not having a side-project, and instead just focus on self-care for a while. Someone posted this on HN a few weeks back and it really hit close to home for me: http://www.robinhobb.com/blog/posts/38429

Anxiety and performance

I’ve recently had to re-evaluate my life and realise that, while there are others who see me as a confident, middle-aged man, that narrative doesn’t bear any kind of scrutiny. Instead, it’s liberating to realise that there is a kind of anxiety which is a two-edged sword; it can propel you forwards and hold you back, depending on how you treat it.

I’d assumed, in my simple two-plus-two way, that people who choose jobs like this found it easy, even enjoyed the thrill. I’m heartened to discover that they, too, feel frightened, their confidence an illusion. And I’m delighted that the shame associated with nervousness, a trait we’re expected to grow out of, has subsided enough for it to be discussed so openly. It’s no coincidence stage fright and its shivering sisters are being talked about now, at a time when even the most confident-seeming people are feeling nervous about re-entering the world.Source: Feeling nervous isn’t bad – it happens to us all | Life and style | The GuardianThe pandemic has helped clarify concepts that previously felt abstract. “Nervousness”, we see now, is not just a childish affectation but a rational reaction to situations that feel dangerous, a feeling experienced by many, and often. Similarly, we are being forced to reconsider the idea of “hope”. Rather than a simple heart-fluttering optimism, hope has been revealed to be both necessary and a bit of a slog. A decision, made daily upon waking, to seek out good news and drag ourselves towards it using our nails, our knees, whatever clawed instrument we have to hand. It prevents us from sinking so deep into the porridge of modern life that we no longer have the energy to look ahead.

Inside your pain are the things you care about most deeply

I listened to this episode of The Art of Manliness podcast a while back on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and found it excellent. I've discussed ACT with my CBT therapist who says it can also be a useful approach.

My guest today says we need to free ourselves from these instincts and our default mental programming and learn to just sit with our thoughts, and even turn towards those which hurt the most. His name is Steven Hayes and he’s a professor of psychology, the founder of ACT — Acceptance and Commitment Therapy — and the author of over 40 books, including his latest 'A Liberated Mind: How to Pivot Toward What Matters'. Steven and I spend the first part of our conversation in a very interesting discussion as to why traditional interventions for depression and anxiety — drugs and talk therapy — aren’t very effective in helping people get their minds right, and how ACT takes a different approach to achieving mental health. We then discuss the six skills of psychological flexibility that undergird ACT and how these skills can be used not only by those dealing with depression and anxiety but by anyone who wants to get out of their own way and show up and move forward in every area of their lives.

Something that Hayes says is that "if people don't know what their values are, they take their goals, the concrete things they can achieve, to be their values". This, he says, is why rich people can still be unfulfilled.

Well worth a listen.

Living with anxiety

It’s taken me a long time to admit it to myself (and my wife) but while I don’t currently suffer from depression, I do live with a low-level general background anxiety that seems to have developed during my adult life.

Wil Wheaton, “actor, blogger, voice actor and writer” and all-round darling of the internet has written in the last few days about his struggles with mental health. My experiences aren’t as extreme as his — I’ve never had panic attacks, and being based from home has made my working life more manageable — but I do relate.

This, in particular, resonated with me from what Wheaton had to say:

One of the many delightful things about having Depression and Anxiety is occasionally and unexpectedly feeling like the whole goddamn world is a heavy lead blanket, like that thing they put on your chest at the dentist when you get x-rays, and it’s been dropped around your entire existence without your consent.The smallest things feel like insurmountable obstacles. One day you're dealing with people and projects across several timezones like an absolute boss, the next day just going to buy a loaf of bread at the local shop feels like a a huge achievement.

We like to think we can control everything in our lives. We can’t.

I'm physically strong: I run, swim, and go to the gym. I (mostly!) eat the right things. My sleep routine is healthy. My family is happy and I feel loved. I've found self-medicating with L-Theanine and high doses of Vitamin D helpful. All of this means I've managed to minimise my anxiety to the greatest extent possible.I think it was then, at about 34 years-old, that I realized that Mental Illness is not weakness. It’s just an illness. I mean, it’s right there in the name “Mental ILLNESS” so it shouldn’t have been the revelation that it was, but when the part of our bodies that is responsible for how we perceive the world and ourselves is the same part of our body that is sick, it can be difficult to find objectivity or perspective.

And yet, out of nowhere, a couple of times a month come waves of feelings that I can’t quite describe. They loom. Everything is not right with the world. It makes no sense to say that they don’t have a particular object or focus, but they really don’t. I can’t put my finger on them or turn what it feels like into words.

Wheaton suggests that often the things we don’t feel like doing in these situations are exactly the things we need to do:

For me, going for a run or playing with my children usually helps enormously. Anything that helps put things into perspective.Give yourself permission to acknowledge that you’re feeling terrible (or bad, or whatever it is you are feeling), and then do a little thing, just one single thing, that you probably don’t feel like doing, and I PROMISE you it will help. Some of those things are:

What I really appreciate in Wheaton’s article, which was an address he gave to NAMI (the American National Alliance on Mental Illness), was that he focused on the experience of undiagnosed children. It’s hard enough as an adult to realise what’s going on, so for children it must be pretty terrible.

If you’re reading this and suffer from anxiety and/or depression, let’s remember it’s 2018. It’s time to open up about all this stuff. And, as Wheaton reminds us, let’s talk to our children about this, too. The chances are that what you’re living with is genetic, so your kids will also have to deal with this at some point.

Source: Wil Wheaton

Meaningless work causes depression

As someone who has suffered in the past from depression, and still occasionally suffers from anxiety, I find this an interesting article:

If you are depressed and anxious, you are not a machine with malfunctioning parts. You are a human being with unmet needs. The only real way out of our epidemic of despair is for all of us, together, to begin to meet those human needs – for deep connection, to the things that really matter in life.Meaningful work is important. Our neoliberal economy is removing much of this under the auspices of 'efficiency'.

Source: The Guardian