Reconstructing Tenochtitlan

This is an absolutely incredible piece of work, showing the complexity and sophistication of the Aztec empire. My favourite part is the slider that allows you to see how much of Mexico City is based upon the structure of Tenochtitlan.

The year is 1518. Mexico-Tenochtitlan, once an unassuming settlement in the middle of Lake Texcoco, now a bustling metropolis. It is the capital of an empire ruling over, and receiving tribute from, more than 5 million people. Tenochtitlan is home to 200.000 farmers, artisans, merchants, soldiers, priests and aristocrats. At this time, it is one of the largest cities in the world.Source: A Portrait of TenochtitlanToday, we call this city Ciudad de Mexico - Mexico City.

Not much is left of the old Aztec - or Mexica - capital Tenochtitlan. What did this city, raised from the lake bed by hand, look like? Using historical and archeological sources, and the expertise of many, I have tried to faithfully bring this iconic city to life.

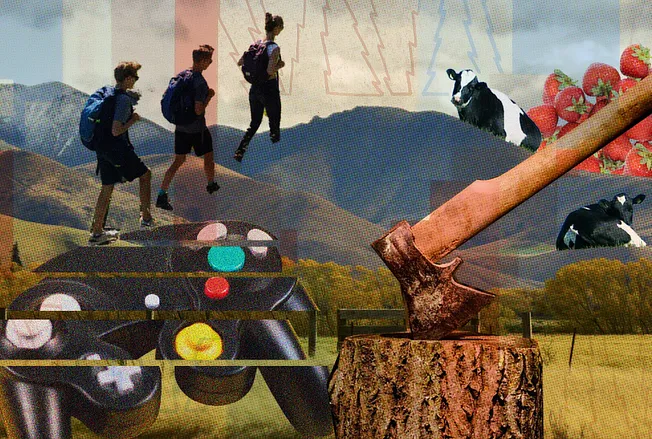

Taking screenagers to the forest

As a parent of a 16 year-old boy and 12 year-old girl I found this article fascinating. Written by Caleb Silverberg, now 17 years of age, it describes his decision to break free from his screen addiction and enrol in Midland, an experiential boarding school located in a forest where technology is forbidden.

Trading his smartphone for an ax, he found liberation and genuine human connection through chores like chopping firewood, living off the land, and engaging in face-to-face conversations. Silverberg advocates for a “Technology Shabbat,” a periodic break from screens, as a solution for his generation’s screen-related issues like ADHD and depression.

At 15 years old, I looked in the mirror and saw a shell of myself. My face was pale. My eyes were hollow. I needed a radical change.Source: Why I Traded My Smartphone for an Ax | The Free PressI vaguely remembered one of my older sister’s friends describing her unique high school, Midland, an experiential boarding school located in the Los Padres National Forest. The school was founded in 1932 under the belief of “Needs Not Wants.” In the forest, cell phones and video games are forbidden, and replaced with a job to keep the place running: washing dishes, cleaning bathrooms, or sanitizing the mess hall. Students depend on one another.

[…]

September 2, 2021, was my first day at Midland, when I traded my smartphone for an ax.

At Midland, students must chop firewood to generate hot water for their showers and heat for their cabins and classrooms. If no one chops the wood or makes the fire, there’s a cold shower, a freezing bed, or a chilly classroom. No punishment by a teacher or adult. Just the disappointment of your peers. Your friends.

[…]

Before Midland, whenever I sat on the couch, engrossed in TikTok or Instagram, my parents would caution me: “Caleb, your brain is going to melt if you keep staring at that screen!” I dismissed their concerns at first. But eventually, I experienced life without an electronic device glued to my hand and learned they were right all along.

[…]

I have been privileged to attend Midland. But anyone can benefit from its lessons. To my generation, I would like to offer a 5,000-year-old solution to our twenty-first-century dilemma. Shabbat is the weekly sabbath in Judaic custom where individuals take 24 hours to rest and relax. This weekly reset allows our bodies and minds to recharge.

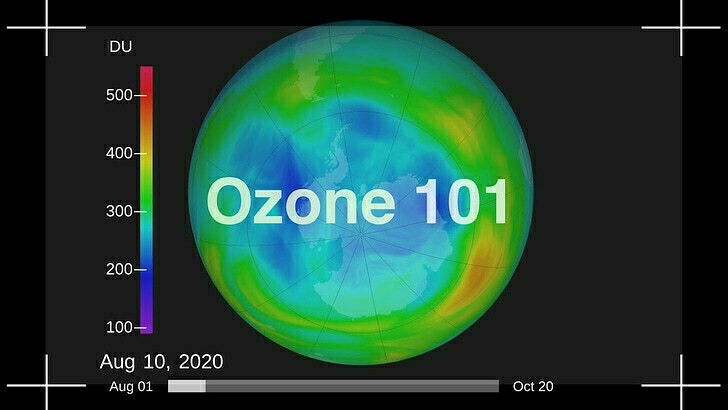

What we can learn about the climate emergency from the world's response to ozone depletion in the 1980s

This article by Andrew Dessler discusses the near-miss catastrophe of ozone depletion. Anyone alive at the time can probably remember how the world came together to address the issue by phasing out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) through the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

Dessler draws parallels with the current climate crisis, arguing that global policy collaboration based on scientific research can solve pressing environmental issues. Along the way, he also debunks claims that transitioning to renewable energy would be economically catastrophic.

In the early 1970s, scientists theorized that certain man-made chemicals, known as chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs, had the potential to reduce the amount of ozone in our atmosphere — this became known as ozone depletion. Given the crucial role of ozone in maintaining a livable environment, this caused great concern.Source: Ozone depletion: The bullet that missed |Andrew DesslerEven before evidence of actual ozone depletion was observed, countries began to take action. For example, the U.S. banned many non-essential uses of the chemicals, such as propellants in aerosol spray cans. This reflected a different view at the time that government should protect its citizens rather than protect the profits of corporations.

By the mid-1980s, the world was busy negotiating the phase-out of the primary ozone-depleting CFCs when the Antarctic ozone hole (AOH) was discovered. The AOH is an annual event: over Antarctica, the majority of the ozone is destroyed during Spring. The ozone builds back up as Spring ends and, by Summer, things are basically back to normal.

[…]

The ‘reference’ future is our world, the ‘world avoided’ is the world that would have existed had we not phased out CFCs. By the 2060s, the world would have lost two-thirds of it’s ozone. This, in turn, would have greatly increased the dangerous ultraviolet radiation reaching the surface. This plot shows the UV dose at noon under clear skies in July in mid-latitudes.

Today’s value of 10 is ‘high risk’ for UV exposure, which is why public health professionals tell you to wear sunscreen when you go out. The world avoided has a UV index of 30 — three times what is considered high risk and high enough to give you a perceptible sunburn in 5 minutes.

Disaster capitalism, climate change, and agriculture

Many readers will be aware of the extreme weather conditions in Vermont USA. This has led to a disastrous year for agriculture and financial struggles for local farmers.

The article delves into the broader implications of these challenges, framing them within the context of ‘disaster capitalism,’ where the degradation of farming and natural resources is exploited for profit, exacerbating systemic issues and inequalities. We’re at the thin of the wedge with this stuff.

Vermont has suffered a miserable growing season and many Vermonters lost a great deal to the flood. Some lost their home and everything in it. But only two people lost their lives, and very few lost their jobs. This is astonishing, given the number of businesses that were shuttered for most of the last eight weeks. Some are still not open. Yes, we may have lost quite a lot, but our losses are marginal compared to the many dozens of people killed in the Maui fire and the billions of dollars of devastation in flooding elsewhere in this country. Similarly, farm losses across the country are measured not in tens of millions, but in billions. Net income from US farming is expected to drop by $30.5 billion, an 18.2% loss over 2022, which was itself not a good year. I’m sure Vermont is in that estimate, but we only add a bit to the decimal places of that number. And these few horrific numbers barely scrape the surface of loss in the US, with even greater horrors mounting everywhere else in the world. (Can Canada even measure the damages sustained in this year’s fires…)Source: The future earth is already here | resilienceThese numbers show that we are in the age of the disaster capitalism described by Naomi Klein after she witnessed the response to Katrina. There has always been more income in the breaking of human lives than in maintaining them. In truth, the 20th century surge in disposable products and planned obsolescence was nothing but extracting profits from breakdown. Similarly, our economy was strongest as it pulled itself out of the devastation of World War II. As long as there are resources and cheap labor somewhere, somebody will profit over our loss. What is different now is that nearly resources and cheap labor are being funneled into this economics of disaster with little left to sustain actual lives.

[…]

We are in disaster capitalism and have been for a long while. I believe that capitalism has always been intrinsically tied to disaster and destruction, whether natural or engineered, but not many people share my views — because my views are from the edge spaces, the bottom and sides of this system. I sit outside and can see things that those dependent on this capitalist system for privilege and wealth do not, or can not. Upton Sinclair’s quip about the inverse relationship between a man’s paycheck and his ability to comprehend any given issue is the duct tape that holds capitalism together in these increasingly disastrous times — increasingly disastrous because of capitalism, whether the result of inadvertent externality or planned waste and breakdown. This system can only survive if enough people refuse to see that its basic function is destruction. Though of course it can also only survive if there are cheap resources and labor to mine for disaster remediation, and we are now entering the stage of late capitalism that has no more cheap things to turn into waste. Capital is feeding on itself, struggling to bring in revenues that can cover its increased costs — costs like fires and floods, scarce resources and a debilitated workforce wracked by disaster. The system needs all the propaganda it can muster to keep telling itself that it is alive and well, keeping those men with dependent paychecks blind to its demise.

Eating the rich is optional, taxing them is mandatory

The article in Insider discusses the findings of the 2022 World Inequality Report, which highlights extreme levels of wealth and income inequality globally. The report was coordinated by leading economists and debunks the trickle-down economic theory.

They found that the bottom half of the global population owns just 2% of total wealth, while the top 10% holds 76%. It also notes that billionaires now hold a 3% share of global wealth, up from 1% in 1995. As everyone knows, inequality is a result of political choices and the only way to fix it is through progressive wealth taxes and perhaps even reparations.

The data serves as a complete rebuke of the trickle-down economic theory, which posits that cutting taxes on the rich will "trickle down" to those below, with the cuts eventually benefiting everyone. In America, trickle-down was exemplified by President Ronald Reagan's tax slashes. It's a theory that persists today, even though most research has shown that 50 years of tax cuts benefits the wealthy and worsens inequality.Source: Huge 20-Year Study Shows Trickle-Down Is a Myth, Inequality Rampant | InsiderThe researchers are some of the leading minds on inequality in the entire field of economics. Chancel is the co-director of the World Inequality Lab, while Saez and Zucman have literally written a book on the rich dodging taxes and helped create wealth tax proposals for senators like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.

[…]

Billionaire gains are a well-documented trend: The left-leaning Institute for Policy Studies and Americans for Tax Fairness found that Americans added $2.1 trillion to their wealth during the pandemic, a 70% increase.

Image: Mathieu Stern

How does doing what I need make time for everything else?

I can’t remember whether someone said to me or I once read that we should manage our energy rather than our time, but it made a big difference to my life. Having control over when and how you work is a huge privilege, and enables you to be the best version of you.

People often smile or laugh when I talk about the SOFA philosophy, but giving yourself the freedom to start creative pursuits and not finish them is actually massively liberating, mood-boosting, and energy-giving.

The point being that you don’t need to ‘make time’ to do things. You just need to prioritise stuff that energises you.

I often find myself listening as someone talks about being out of time. Even the most progressive and thoughtful organizations regularly cultivate situations where the amount of work outstrips the capacity of the people in place to do it. Combine that with our appalling lack of support for caretakers, the administrative burden of accessing your healthcare, the often thankless tasks of keeping house and home, and it’s no wonder that even the people most trained in solving tricky problems run into a hard wall with this one.Source: Energy makes time | everything changes[…]

We all know that time can be stretchy or compressed—we’ve experienced hours that plodded along interminably and those that whisked by in a few breaths. We’ve had days in which we got so much done we surprised ourselves and days where we got into a staring contest with the to-do list and the to-do list didn’t blink. And we’ve also had days that left us puddled on the floor and days that left us pumped up, practically leaping out of our chairs. What differentiates these experiences isn’t the number of hours in the day but the energy we get from the work. Energy makes time.

Here’s a concrete example, and perhaps a familiar one: someone is so busy with work and caretaking that they don’t make time for their art. At the end of the day they’re too tired to write or paint or make music or whathaveyou. So they don’t. Days, then weeks go by. They are more and more tired. They are getting less and less done. They take a mental health day and catch up on sleep but the exhaustion persists. Their overwhelm grows larger, becomes intolerable. The usual tactics don’t work..

Then one day they say fuck it all. They eat leftover pasta over the sink, drop mom off at her mahjongg game, and go sit in the park to draw. They draw for hours, until the sun goes down and they’re squinting under the street lights. And, lo and behold, the next day they plow through all those lingering to-dos. They see clearly that half of them were unnecessary when before they all seemed critical. They recognize a few others as things better handed off to their peers. They suddenly find time for attending to that one project they’d been procrastinating on for weeks. They sleep better. Their skin looks great. (Okay I might be exaggerating on that last one, but only mildly.)

It turns out, not doing their art was costing them time, was draining it away, little by little, like a slow but steady leak. They had assumed, wrongly, that there wasn’t enough time in the day to do their art, because they assumed (because we’re conditioned to assume) that every thing we do costs time. But that math doesn’t take energy into account, doesn’t grok that doing things that energize you gives you time back. By doing their art, a whole lot of time suddenly returned. Their art didn’t need more time; their time needed their art.

[…]

The question to ask with all those things isn’t, “how do I make time for this?” The answer to that question always disappoints, because that view of time has it forever speeding away from you. The better question is, how does doing what I need make time for everything else?

Image: Aron Visuals

Note taking tools and processes

Casey Newton delves into the limitations of current note-taking apps like Obsidian, arguing that they are designed more for storing information than for sparking insights or improving thinking. He suggests that while AI has the potential to revolutionise these platforms by making them more interactive and insightful, the real challenge lies in our ability to focus and think deeply — something that software alone cannot automate.

This is partly why I write Thought Shrapnel. Not only does it force me to actually read things I’ve bookmaked, but I make sense of them, and often make links to my work and other things I’ve read.

Note-taking, after all, does not take place in a vacuum. It takes place on your computer, next to email, and Slack, and Discord, and iMessage, and the text-based social network of your choosing. In the era of alt-tabbing between these and other apps, our ability to build knowledge and draw connections is permanently challenged by what might be our ultimately futile efforts to multitask.Source: Why note-taking apps don’t make us smarter | Platformer[…]

In short: it is probably a mistake, in the end, to ask software to improve our thinking. Even if you can rescue your attention from the acid bath of the internet; even if you can gather the most interesting data and observations into the app of your choosing; even if you revisit that data from time to time — this will not be enough. It might not even be worth trying.

The reason, sadly, is that thinking takes place in your brain. And thinking is an active pursuit — one that often happens when you are spending long stretches of time staring into space, then writing a bit, and then staring into space a bit more. It’s here that the connections are made and the insights are formed. And it is a process that stubbornly resists automation.

Which is not to say that software can’t help. Andy Matuschak, a researcher whose spectacular website offers a feast of thinking about notes and note-taking, observes that note-taking apps emphasize displaying and manipulating notes, but never making sense between them. Before I totally resign myself to the idea that a note-taking app can’t solve my problems, I will admit that on some fundamental level no one has really tried.

Poverty is expensive. Cash helps homeless people.

Real-world studies such as this are important for busting myths about homeless people spending money recklessly compared to the rest of us.

The widely held stereotype that people experiencing homelessness would be more likely to spend extra cash on drugs, alcohol and “temptation goods” has been upended by a study that found a majority used a $7,500 payment mostly on rent, food, housing, transit and clothes.Source: Canada study debunks stereotypes of homeless people’s spending habits | The GuardianThe biases punctured by the study highlight the difficulties in developing policies to reduce homelessness, say the Canadian researchers behind it. They said the unconditional cash appeared to reduce homelessness, giving added weight to calls for a guaranteed basic income that would help adults cover essential living expenses.

[…]

They found the cash recipients each spent an average of 99 fewer days homeless than the control group, increased their savings more and also “cost” society less by spending less time in shelters.

[…]

Researchers ensured the cash was in a lump sum “to enable maximum purchasing freedom and choice” as opposed to small, consistent transfers.

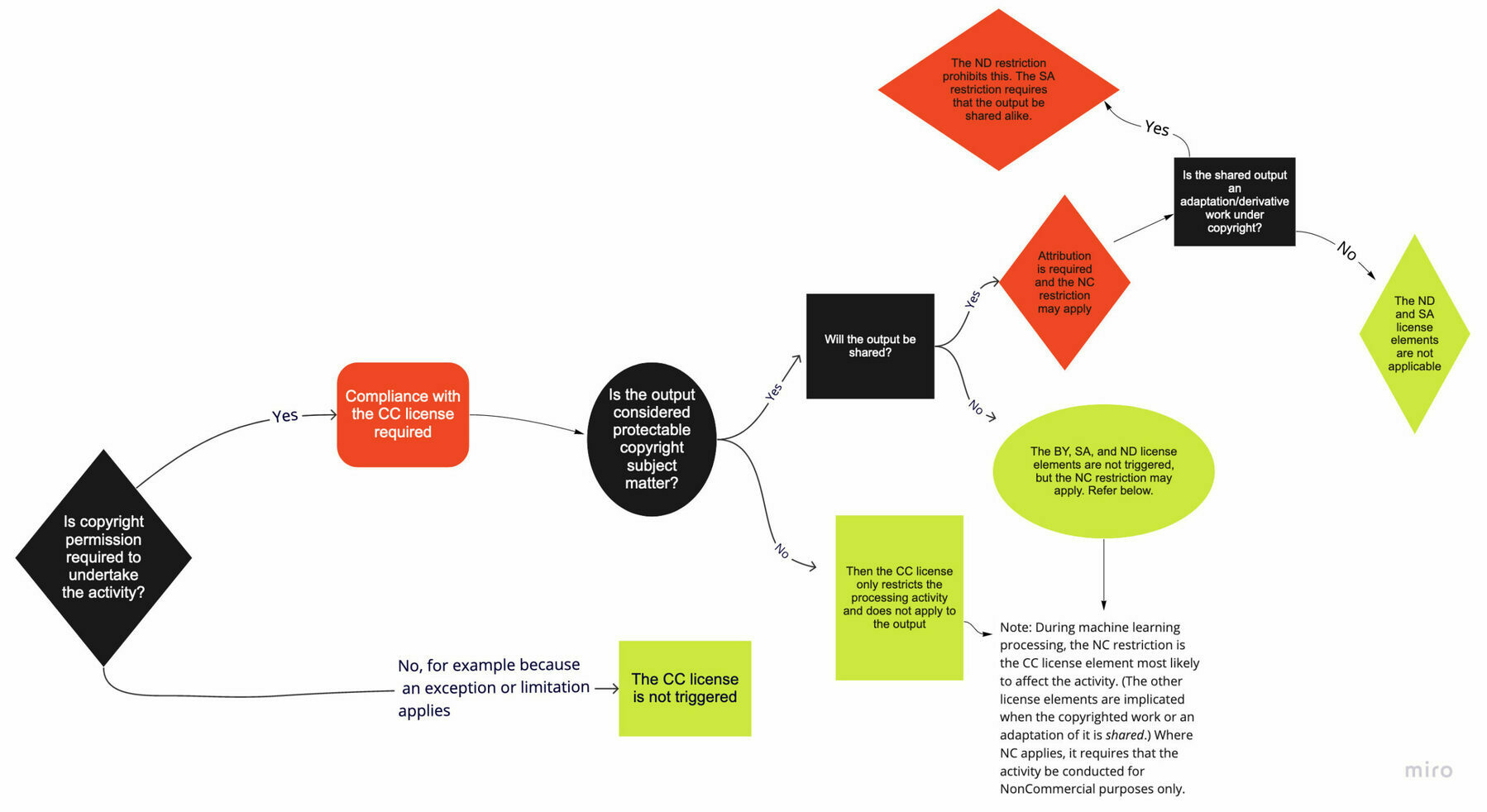

Can you use CC licenses to restrict how people use copyrighted works in AI training?

TL;DR seems to be that copyright isn’t going to prevent people data mining content to use for training AI models. However, there are protections around privacy that might come into play.

This is among the most common questions that we receive. While the answer depends on the exact circumstances, we want to clear up some misconceptions about how CC licenses function and what they do and do not cover.Source: Understanding CC Licenses and Generative AI | Creative CommonsYou can use CC licenses to grant permission for reuse in any situation that requires permission under copyright. However, the licenses do not supersede existing limitations and exceptions; in other words, as a licensor, you cannot use the licenses to prohibit a use if it is otherwise permitted by limitations and exceptions to copyright.

This is directly relevant to AI, given that the use of copyrighted works to train AI may be protected under existing exceptions and limitations to copyright. For instance, we believe there are strong arguments that, in most cases, using copyrighted works to train generative AI models would be fair use in the United States, and such training can be protected by the text and data mining exception in the EU. However, whether these limitations apply may depend on the particular use case.

A philosophy of travel

There’s a book by philosopher Alain de Botton called The Art of Travel. In it, he cites Seneca as bemoaning the fact that when you travel you take yourself, with all of your anxieties, frustrations, and insecurities with you. In other words, you might escape your home, but you don’t escape yourself.

This article critically examines the concept of travel, questioning its oft-claimed benefits of ‘enlightenment’ and ‘personal growth’. It cites various thinkers who have critiqued travel (including one of my favourites, Fernando Pessoa) suggesting that it can actually distance us from genuine human connection and meaningful experiences.

It’s hard not to agree with the conclusion that the allure of travel may lie in its ability to temporarily distract us from the existential dread of mortality. Perhaps we need more Marcus Aurelius in our life, who extolled one the benefits of philosophy as being able to be find calm no matter where you are.

“A tourist is a temporarily leisured person who voluntarily visits a place away from home for the purpose of experiencing a change.” This definition is taken from the opening of “Hosts and Guests,” the classic academic volume on the anthropology of tourism. The last phrase is crucial: touristic travel exists for the sake of change. But what, exactly, gets changed? Here is a telling observation from the concluding chapter of the same book: “Tourists are less likely to borrow from their hosts than their hosts are from them, thus precipitating a chain of change in the host community.” We go to experience a change, but end up inflicting change on others.Source: The Case Against Travel | The New YorkerFor example, a decade ago, when I was in Abu Dhabi, I went on a guided tour of a falcon hospital. I took a photo with a falcon on my arm. I have no interest in falconry or falcons, and a generalized dislike of encounters with nonhuman animals. But the falcon hospital was one of the answers to the question, “What does one do in Abu Dhabi?” So I went. I suspect that everything about the falcon hospital, from its layout to its mission statement, is and will continue to be shaped by the visits of people like me—we unchanged changers, we tourists. (On the wall of the foyer, I recall seeing a series of “excellence in tourism” awards. Keep in mind that this is an animal hospital.)

Why might it be bad for a place to be shaped by the people who travel there, voluntarily, for the purpose of experiencing a change? The answer is that such people not only do not know what they are doing but are not even trying to learn. Consider me. It would be one thing to have such a deep passion for falconry that one is willing to fly to Abu Dhabi to pursue it, and it would be another thing to approach the visit in an aspirational spirit, with the hope of developing my life in a new direction. I was in neither position. I entered the hospital knowing that my post-Abu Dhabi life would contain exactly as much falconry as my pre-Abu Dhabi life—which is to say, zero falconry. If you are going to see something you neither value nor aspire to value, you are not doing much of anything besides locomoting.

[…]

The single most important fact about tourism is this: we already know what we will be like when we return. A vacation is not like immigrating to a foreign country, or matriculating at a university, or starting a new job, or falling in love. We embark on those pursuits with the trepidation of one who enters a tunnel not knowing who she will be when she walks out. The traveller departs confident that she will come back with the same basic interests, political beliefs, and living arrangements. Travel is a boomerang. It drops you right where you started.

[…]

Travel is fun, so it is not mysterious that we like it. What is mysterious is why we imbue it with a vast significance, an aura of virtue. If a vacation is merely the pursuit of unchanging change, an embrace of nothing, why insist on its meaning?

Using semesters for goal-setting

This article suggests using the academic calendar as a framework for setting and achieving personal goals, breaking life into “semesters” to focus on mini-goals that contribute to larger ambitions. It argues that this approach can aid in time management, motivation, and skill development, offering a structured yet flexible way to make meaningful progress in various aspects of life.

As someone who spent a long time in formal education, was a teacher, and spent time working in Higher Education, it’s difficult to get out of the habit of the academic year and breaking your work into ‘terms’. Perhaps I should be leaning into it?

While it’s important to set goals, the roadmap for how to attain them can be murky. Instead of embarking without a plan toward broad ambitions, there’s value in incremental objectives in service of a larger aim. Take a page from the educational system and divide the future into “semesters” — traditionally 15 to 17 weeks long at American colleges — in which to implement minigoals to help get you where you want to go. Use the traditional academic year as a guide to help you stay on track, says Rachel Wu, an associate professor of psychology at the University of California Riverside. Many community classes and educational opportunities are offered roughly on a quarter or semester basis. “At the very least, it will help people, maybe, feel young again. I think that’s a huge benefit,” Wu says. “They can think back to that point in their life when they had that kind of organization and that might be something that works for them.” (You don’t need to follow a traditional academic structure by any means, but having a firm start and end date within a few months’ span in which to focus on certain skills or activities can help keep you motivated.)Source: Semesters for adults: How the academic school year can help with goal-setting, time management, and motivation | Vox[…]

Modeling your life after academic years allows you to adequately mark your process. It’s difficult to determine improvement with daily or even weekly goals, Fishbach says. But with a quarterly or biannual milestone, you’re more easily able to track your progress; you can more clearly look back on what you’ve learned after a 20-week intro to coding class as opposed to after a few days of instruction. The end of a semester allows for these report cards. “It just helps you feel that you’re growing as a person,” Fishbach says. “You’re not the person you were three months ago.”

[…]

A self-imposed semester system also lends itself to increased motivation due, in part, to the fresh start effect, where people are more driven to pursue goals after a “fresh start” like a new year or semester. (Fully embrace the back-to-school energy and buy some new school supplies, Wu says, “and then learn something.”) With goals that have an endpoint, called an all-or-nothing goal, Fishbach says, motivation increases as you approach the deadline. Having a distinct cutoff to your personal semester can help you stay driven knowing there’s an end in sight.

The uninhabitable earth

This interactive tool maps in 3D where our planet will become unihabitable due to a combination of heat, water stress, sea level rise, and tropical cyclones.

It’s an amazing and depressing visualisation, which indirectly shows how climate migration will inevitably increase in the coming decades.

Climate change is destroying people's livelihoods. By the year 2100, all areas that are red in the visualisation will become “uninhabitable”. Extreme heat, tropical cyclones, rising sea levels, water stress or a combination of those are projected to make it difficult or impossible to live there.Source: Climate change: Mapping in 3D where the earth will become uninhabitable | Berliner Morgenpost

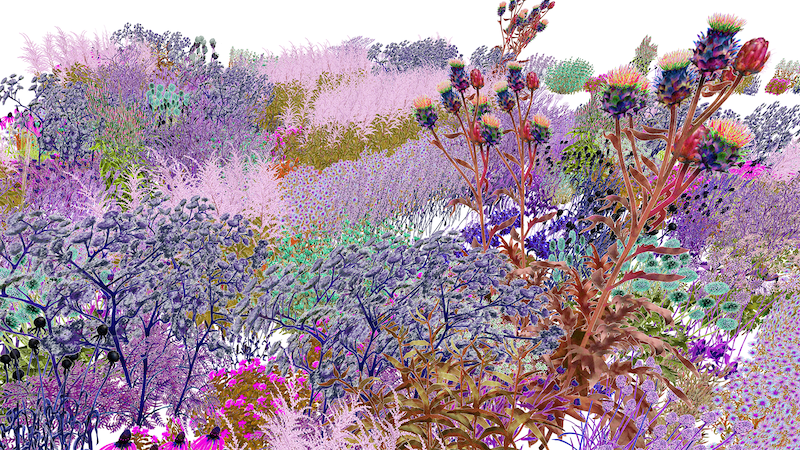

The world's largest climate-positive artwork provides food and nesting spots via algorithm

It’s interesting that this is being conceptualised as an ‘artwork’ rather than a technological intervention. Perhaps this is the way to deal with the climate crisis, by bringing algorithms from the cold, sterile environment of technology into the warmer, more joyful world of art?

This multidisciplinary project by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg explores the relationship between humans, nature, and technology and aims to draw attention to the importance of insects in pollination by creating an algorithmic solution for planting designs that serve a diverse range of pollinator species.

The project changes depending on location, debuting at the Eden Project in 2021 and includes 7,000 plants across 80 varieties. These provide food and nesting spots for insects with the aim to create the world’s largest climate-positive artwork.

This is not a natural ecosystem planted outside, there are plants from all over the world. With the expert group, we chose not to focus on native plants only because they are locally appropriate so they’re not invasive. So that’s the first thing—it’s an artificial landscape designed for nature, so it’s a very different way of creating an ecosystem. The other big challenge to the art world that I’m proposing is creating a climate-positive artwork. I also show in museums and I use digital media and that’s all very carbon-consuming. Here, we actually have an artwork fabricated in plants. It has its own climate impact because of the soil we’re moving, the plastic pots, the shipping of plants, but it’s here for at least three years, so it starts to outweigh that negative. There’s also a question of how we measure that, and that’s something I’m really interested in.Source: An Interview with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg | Berlin Art LinkThe other thing that’s really important to me is upending the idea of value. The art market is all about the one, the singular, the limited edition. This is an unlimited edition. The idea is: the more people who have one, the better each one is because each one supports the other. For me, that’s a strong statement to make to commissioners and when I’m trying to get more partners involved. It’s a very different way of thinking about how we create art and what its purpose is. For me, this is about playfulness, joy and celebrating nature. I call it an artwork and not a garden project because I think situating it in that context makes a powerful statement in itself.

AI and bullshit jobs

I had the pleasure of working with the large-brained Helen Beetham when I was at Jisc just over a decade ago. In this long-ish post, she covers quite a few areas of, with plenty of links, and pulls the threads together around graduate jobs and an AI curriculum.

While I could have quoted a lot of this, especially around innovation, the stories being told to graduates, and the neo-colonial nature of AI companies, I’ve gone for the last three paragraphs in which Helen discusses bullshit jobs. I’d highly recommend reading the whole thing.

My hope is that, rather than a curriculum ‘for AI’, these conversations would create space for learning that addresses human challenges. Getting life on earth out of the mess that fossil fuels and rampant production have made of it will take all the graduate labour we can produce and more. Nobody is going to be without meaningful work - not climate scientists or green energy specialists or engineers or geologists or computer scientists or materials chemists or statisticians. Not a single person educated in the STEM subjects beloved of governments everywhere can be left idle. But nor are we getting out of this without social scientists to help us weather the social and economic and political storms, humanities graduates to develop new laws and policies, new philosophies and imagined futures, and professionals committed to a just transition in their own spheres of work. And there are other crises, entwined with the climate crisis, that graduates need and want to address, such as galloping economic inequality, crises of democracy and human rights, food and water shortages, and the crisis of care. Universities can offer fewer and fewer guarantees of secure employment and decent pay, but they can offer meaningful work, justifying students’ investment in the future.Source: ‘Luckily, we love tedious work’ | Helen BeethamThe longer you look at the things ChatGPT can do, the more they resemble what David Graeber described as Bullshit Jobs - jobs that don’t need doing. While I don’t agree with the way he singles out specific job roles, Graeber is surely right that more and more work involves doing things with data and information and ‘content’ that has no value beyond maintaining those systems. And one claim he made that is borne out by workplace research is that meaningless work is bad for people’s mental health.

It’s a nice little aphorism that ‘if AI can do your job, AI should do your job’. But here’s a different one. If AI can ‘do’ your job, you deserve a better job. And if meaningless jobs are bad for workers’ mental health, how much worse are they for all our futures? The phrase ‘fiddling while Rome burns’ hardly begins to cover our present situation. As the polycrisis heats up, the crisis of not enough water-cooler text is not something any graduate should have to care about, nor any university curriculum either.

We need to talk about AI porn

Thought Shrapnel is a prude-free zone, especially as the porn industry tends to be a technological innovator. It’s important to say, though, that the objectification of women and non-consensual generation of pornography is not just a bad thing but societally corrosive.

By now, we’re familiar with AI models being able to create images of almost anything. I’ve read of wonderful recent advances in the world of architecture, for example. Some of the most popular AI generators have filters to prevent abuse, but of course there are many others.

As this article details, a lot of porn has already been generated. Again, prudishness aside relating to people’s kinks, there are all kind of philosophical, political, legal, and issues at play here. Child pornography is abhorrent; how is our legal system going to deal with AI generated versions? What about the inevitable ‘shaming’ of people via AI generated sex acts?

All of this is a canary in the coalmine for what happens in society at large. And this is why philosophical training is important: it helps you grapple with the implications of technology, the ‘why’ as well as the what. I’ve got a lot more thoughts on this, but I actually think it would be a really good topic to discuss as part of the next season of the WAO podcast.

“Create anything,” Mage.Space’s landing page invites users with a text box underneath. Type in the name of a major celebrity, and Mage will generate their image using Stable Diffusion, an open source, text-to-image machine learning model. Type in the name of the same celebrity plus the word “nude” or a specific sex act, and Mage will generate a blurred image and prompt you to upgrade to a “Basic” account for $4 a month, or a “Pro Plan” for $15 a month. “NSFW content is only available to premium members.” the prompt says.Source: Inside the AI Porn Marketplace Where Everything and Everyone Is for Sale | 404 Media[…]

Since Mage by default saves every image generated on the site, clicking on a username will reveal their entire image generation history, another wall of images that often includes hundreds or thousands of AI-generated sexual images of various celebrities made by just one of Mage’s many users. A user’s image generation history is presented in reverse chronological order, revealing how their experimentation with the technology evolves over time.

Scrolling through a user’s image generation history feels like an unvarnished peek into their id. In one user’s feed, I saw eight images of the cartoon character from the children’s’ show Ben 10, Gwen Tennyson, in a revealing maid’s uniform. Then, nine images of her making the “ahegao” face in front of an erect penis. Then more than a dozen images of her in bed, in pajamas, with very large breasts. Earlier the same day, that user generated dozens of innocuous images of various female celebrities in the style of red carpet or fashion magazine photos. Scrolling down further, I can see the user fixate on specific celebrities and fictional characters, Disney princesses, anime characters, and actresses, each rotated through a series of images posing them in lingerie, schoolgirl uniforms, and hardcore pornography. Each image represents a fraction of a penny in profit to the person who created the custom Stable Diffusion model that generated it.

[…]

Generating pornographic images of real people is against the Mage Discord community’s rules, which the community strictly enforces because it’s also against Discord’s platform-wide community guidelines. A previous Mage Discord was suspended in March for this reason. While 404 Media has seen multiple instances of non-consensual images of real people and methods for creating them, the Discord community self-polices: users flag such content, and it’s removed quickly. As one Mage user chided another after they shared an AI-generated nude image of Jennifer Lawrence: “posting celeb-related content is forbidden by discord and our discord was shut down a few weeks ago because of celeb content, check [the rules.] you can create it on mage, but not share it here.”

Raising the average level of creativity using AI

Like most infants, my daughter wanted to speak before she was able to. Unlike most infants, she was extremely frustrated that she couldn’t do so.

Most people can’t draw as well as they would like. Many people become exasperated when they can’t adequately express their ideas in written form.

AI can help with all of this and, in my case, already is. This article, which draws on the results of three academic studies, is interesting in terms of how we can raise the average level of human creativity with the use of AI.

Each of the three papers directly compares AI-powered creativity and human creative effort in controlled experiments. The first major paper is from my colleagues at Wharton. They staged an idea generation contest: pitting ChatGPT-4 against the students in a popular innovation class that has historically led to many startups. The researchers — Karan Girotra, Lennart Meincke, Christian Terwiesch, and Karl Ulrich — used human judges to assess idea quality, and found that ChatGPT-4 generated more, cheaper and better ideas than the students. Even more impressive, from a business perspective, was that the purchase intent from outside judges was higher for the AI-generated ideas as well! Of the 40 best ideas rated by the judges, 35 came from ChatGPT.Source: Automating creativity | Ethan MollickA second paper conducted a wide-ranging crowdsourcing contest, asking people to come up with business ideas based on reusing, recycling, or sharing products as part of the circular economy. The researchers (Léonard Boussioux, Jacqueline N. Lane, Miaomiao Zhang, Vladimir Jacimovic, and Karim R. Lakhani) then had judges rate those ideas, and compared them to the ones generated by GPT-4. The overall quality level of the AI and human-generated ideas were similar, but the AI was judged to be better on feasibility and impact, while the humans generated more novel ideas.

The final paper did something a bit different, focusing on creative writing ideas, rather than business ideas. The study by Anil R. Doshi and Oliver P. Hauser compared humans working alone to write short stories to humans who used AI to suggest 3-5 possible topics. Again, the AI proved helpful: humans with AI help created stories that were judged as significantly more novel and more interesting than those written by humans alone. There were, however, two interesting caveats. First, the most creative people were helped least by the AI, and AI ideas were generally judged to be more similar to each other than ideas generated by people. Though again, this was using AI purely for generating a small set of ideas, not for writing tasks.

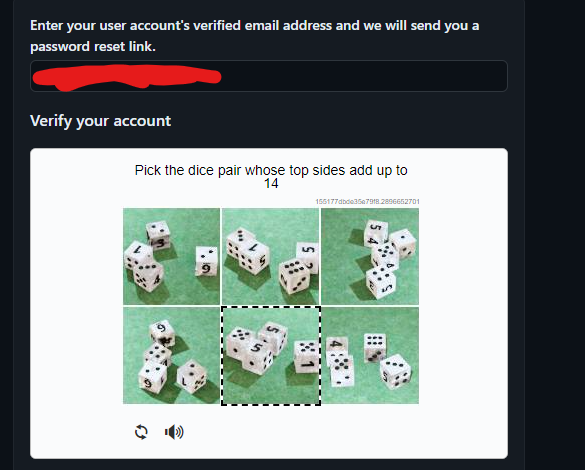

CAPTCHA is an arms race we're losing against AI bots

I saw a story that GitHub’s CAPTCHA had become ridiculously hard and multiple people weren’t able to solve it within the time limit. GitHub have presumably upgraded their system because the version we’ve come to know and despise (“click on all of the traffic lights”) is now solved faster by AI than by humans.

“Life is a campaign against malice” said the 17th century Jesuit priest and philosopher Baltasar Gracián. How right he was.

You definitely have tried to access some websites and have gotten bombarded with a series of puzzles requiring you to correctly identify traffic lights, buses, or crosswalks to prove that you’re indeed human before you log in.Source: AI bots are better than humans at solving CAPTCHA puzzles | QuartzKnown as Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart (CAPTCHA), the technology is intended to protect a website from fraud and abuse without creating friction. The puzzles are meant to ensure that only valid users are able to access the site and not automated invasions.

Google replaced CAPTCHA with a more advanced tool called reCAPTCHA in 2019, but the team’s technical lead Aaron Malenfant told the Verge at the time that the technology would no longer be viable in 10 years’ time because advanced tech would allow the Turing test to run in the background.

His prediction was right. Artificial Intelligence (AI) bots are fast-evolving and are now beating the reCAPTCHA methodology used to confirm the validity and personhood of the users of various websites. They do this by imitating how the human brain and vision work. In fact, AI bots are measuring up to humans, and even beating them, in numerous facets.

When it's getting too hot for plants to photosynthesize, you know we've got a problem

I used to run a site called extinction.fyi which documented the climate emergency. This definitely would have been an article I would have featured on there.

As would the news that French nuclear power stations had to stop running when the water in the rivers next to where they’re situated became too hot. The additional heat of water coming out of the cooling circuits would raise the temperature further, killing aquatic life.

Leaves in the world’s tropical forests are approaching critical temperatures at which photosynthesis breaks down—and a fraction have likely already passed that threshold—raising alarms about the fate of these essential ecosystems under the most pessimistic projections of human-driven climate change, reports a new study.Source: It’s Getting Too Hot for Tropical Trees to Photosynthesize, Scientists Warn | VICE[…]

The ECOSTRESS data, along with follow-up measurements from the ground, showed that tropical canopy temperatures tend to peak at around 34°C, though some regions experienced temperatures that exceeded 40°C. Because there is a surprising amount of temperature variation between the individual leaves on a single tree, the researchers estimated that about a tenth of a percent of all leaves in tropical forests are annually pushed beyond the critical threshold of 46.7°C that marks the breaking point of photosynthesis.

[…]

As global temperatures continue to rise, more tropical leaves will be pushed beyond their photosynthetic capabilities, causing plants to perish. While the researchers emphasized that there is a lot of uncertainty in their models, they warned that an increase in global air temperatures of about 3.9°C could trigger a major photosynthetic meltdown for tropical forests. This estimated increase is within the range of climate models that project a future where human greenhouse gas emissions don’t begin to fall until after 2080.

Structural insecurity

This fantastic piece by Astra Taylor, whose book The Age of Insecurity is on my to-read list, is sadly behind a paywall. I managed to bypass it, which is why I’m excerpting so much in this post.

What I like is the separation of inequality from insecurity and the difference between existential insecurity from ‘manufactured’ insecurity. Being published in The New York Times, the context is the American economy which largely exists without a social safety net.

The situation is better in the UK/Europe, but we still live in a much more economically precarious world than our parents and grandparents did. And perhaps that’s why everyone’s anxious all of the time.

Since 2020, the richest 1 percent has captured nearly two-thirds of all new wealth globally — almost twice as much money as the rest of the world’s population. At the beginning of last year, it was estimated that 10 billionaire men possessed six times as much wealth as the poorest three billion people on Earth. In the United States, the richest 10 percent of households own more than 70 percent of the country’s assets.Source: Why Does Everyone Feel So Insecure All the Time? | The New York TimesSuch statistics are appalling. They have also become familiar. Since it was catapulted onto the national stage more than a decade ago by Occupy Wall Street, “inequality” has been a frequent topic of conversation in American political life. It helped animate Bernie Sanders’s influential campaigns, reshaped academic scholarship, shifted public policy, and continues to galvanize protest. And yet, however important focusing on the inequality crisis has been, it has also proven insufficient.

If we want to understand contemporary economic life, we need a more expansive framework. We need to think about insecurity. Where inequality encourages us to look up and down, to note extremes of indigence and opulence, insecurity encourages us to look sideways and recognize potentially powerful commonalities.

If inequality can be captured in statistics, insecurity requires talking about feelings: It is, to borrow a phrase from feminism, personal as well as political. Economic issues, I’ve come to realize, are also emotional ones: the spike of shame when a bill collector calls, the adrenaline when the rent or mortgage is due, the foreboding when you think about retirement.

And unlike inequality, insecurity is more than a binary of haves and have-nots. Its universality reveals the degree to which unnecessary suffering is widespread — even among those who appear to be doing well. We are all, to varying degrees, overwhelmed and apprehensive, fearful of what the future might have in store. We are on guard, anxious, incomplete and exposed to risk. To cope, we scramble and strive, shoring ourselves up against potential threats. We work hard, shop hard, hustle, get credentialed, scrimp and save, invest, diet, self-medicate, meditate, exercise, exfoliate.

[…]

Rather than something to pathologize, I want us to see insecurity as an opportunity. We all need protection from life’s hazards, natural or human-made. The simple acceptance of our mutual vulnerability — of the fact that we all need and deserve care throughout our lives — has potentially transformative implications. When we spur people on with insecurity because we expect the worst from them, we create a vicious cycle that stokes desperation and division while facilitating the kind of cutthroat competition and consumption that has brought our fragile planet to a catastrophic brink. When we extend trust and support to others, we improve everyone’s security — including our own.

[…]

Insecurity, after all, is what makes us human, and it is also what allows us to connect and change. “Nothing in Nature ‘becomes itself’ without being vulnerable,” writes the physician Gabor Maté in “The Myth of Normal.” “The mightiest tree’s growth requires soft and supple shoots, just as the hardest-shelled crustacean must first molt and become soft.” There is no growth, he observes, without emotional vulnerability.

The same also applies to societies. Recognizing our shared existential insecurity, and understanding how it is currently used against us, can be a first step toward forging solidarity. Solidarity, in the end, is one of the most important forms of security we can possess — the security of confronting our shared predicament as humans on this planet in crisis, together.